In a recent article that explores attempts to embed an innovative information literacy (IL) framework in undergraduate political science courses, Harden and Harden (Reference Harden and Harden2020, 344) claimed that “Political science faculty often express discontent over undergraduate students’ lack of preparedness for college-level research and writing.” A particular concern is the perceived failure of many students to use appropriate sources in their coursework, an indication that they are not as information literate as they need to be to thrive in the political science classroom. Using data compiled from a worldwide survey of political science faculty, this article explores this observation in detail. For example, we examine whether this perception of inadequate IL among political science students is universal.

This article also uncovers significant details about the nature of IL education in many political science classrooms. This is useful because the position of IL throughout the university curriculum has been called into question. As Fister (Reference Fister2021) argued, “This kind of learning has no specific place on the curriculum. It’s everywhere, and nowhere. It’s everybody’s job, but nobody’s responsibility.” As we demonstrate, the political science classroom is no exception. We show that participation by library staff in political science courses is sporadic at best and that only a minority of faculty report having received IL training. An important finding is that faculty members who have participated in explicit IL training are more likely to introduce it to their students. This finding leads us to suggest that more IL training should be provided at the faculty level. Ultimately, however, our key suggestion is that irrespective of who leads the process—whether faculty or information specialists—IL must be granted a more prominent place in the curriculum. This is a matter not only of pedagogy; it also has wider political significance. As Goldstein (Reference Goldstein and Goldstein2020, xxv) suggested, IL is “a vital factor in the functioning of a healthy, inclusive, participatory society.”

INFORMATION LITERACY

IL is the concept most associated with the educational practice of helping people negotiate effectively and ethically the world of information, which has been made even more treacherous by the near-eclipse of print sources by information available through smartphones and other suitably connected electronic devices. A product of the 1970s, IL initially was defined as a set of skills but since then has become a more critical, multidimensional concept (Association of College and Research Libraries 2015). A recent influential definition suggests that “information literacy is the ability to think critically and make balanced judgments about and information we find and use. It empowers us as citizens to develop informed views and to engage fully with society” (Information Literacy Group 2018, 3). In the hazardous information environment of the twenty-first century, IL—at some level—has become regarded as an attribute essential for performing even the most basic of academic tasks.

INFORMATION LITERACY IN THE CLASSROOM

Although the case for society in general and students in particular to embrace IL has never been clearer, it is not obvious that much has changed in the classroom in recent decades. In 2006, McGuinness (Reference McGuinness2006, 573–74) suggested that “despite an ideological commitment to pedagogical innovation within the postsecondary sector, in many cases, the inclusion of IL, both as a desired outcome and as a tool of undergraduate education, remains an aspiration rather than a fully realized ideal.” In 2022, the impression remains that this aspiration is yet to be realized. Considering the situation in the political science classroom, Harden and Harden (Reference Harden and Harden2020, 347) remarked, “[f]aculty often place such a high premium on substantive knowledge in their classes that they overlook the need to help students develop those skills during the course of a term.”

Indeed, rather than mere stasis, some commentators have noticed signs of retreat. For example, in light of the attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, Fister (Reference Fister2021) identified various reasons for the pervasiveness of misinformation, even on university campuses. These reasons include the low status of librarians, a lack of consistent instruction about information and media literacy, the diminishment of humanities as a core element of education, and the problems that arise with rapid technological change. As noted previously, the critical factor that Fister (Reference Fister2021) identified is the absence of a settled place for IL in the curriculum, being simultaneously “everywhere and nowhere.” To expand on this, universities tend to be in the paradoxical position that those who decide whether IL even happens are academic faculty, who may not have training in IL, may not think that it is important—and, indeed, may not even know that it exists. As Goldstein (Reference Goldstein and Goldstein2020, xiv) noted, “[i]n spite of its power as a concept, information literacy is not widely recognized as a term outside the realms of the information professions and of information science.” Conversely, those who do know about IL and possess the necessary expertise—librarians and other information professionals—tend not to possess a powerful voice in determining what is taught in the university classroom.

Although IL is not an overpopulated area of research, studies have questioned faculty members about the nature of IL education to provide insight into its underappreciated position in the university curriculum. For example, various studies (e.g., DaCosta Reference DaCosta2010; Dubicki Reference Dubicki2013) discovered that faculty across all disciplines generally claim to regard IL as an important part of the academic curriculum. They also pointed out that faculty often suggest that undergraduate IL competencies tend to be underwhelming and that something should be done to improve the situation. Scholars including Saunders (Reference Saunders2012) found that faculty are particularly concerned that many students lack the necessary skills to engage critically with the information they discover. Students often treat all sources—from academic articles to Google searches—as equally authoritative.

These surveys found agreement between faculty and information professionals that a problem exists and must be addressed. However, some research suggests that the commitment of faculty to IL is superficial at best. For example, a study by Nilsen (Reference Nilsen2012) found that—despite faculty members rating IL skills and instruction as “very important” to students in their discipline—almost half of the respondents indicated that they do not regularly request in-class library instruction for any of their courses.

According to McGuinness (Reference McGuinness2006, 577), this failure stems from the “tacit assumption among faculty that students will somehow absorb and develop the requisite knowledge and skills through the very process of preparing a piece of written work coursework, and by applying the advice of their supervisors.” McGuiness added that this is not sufficient because it leaves the ability to become information literate almost entirely dependent on the innate capabilities of the student. DaCosta (Reference DaCosta2010, 218) was similarly unconvinced by this process of passive learning, stating that “there is an apparent gap between the information skills that faculty want their students to have and those they actively support and develop.”

However, as Bury (Reference Bury2016) suggested, it would be simplistic to assume that because faculty members often fail to include informational specialists in their classroom that IL is not regarded as an important part of the curriculum. Bury’s (Reference Bury2016) own survey—which entailed 24 semi-structured interviews with faculty from various disciplines—highlighted that most faculty wanted to do more but did not believe that they had the time or the expertise. Dawes (Reference Dawes2019) made a similar point. Reflecting on the importance of the first-year provision, she concentrated on that specific academic year, conducting 24 semi-structured interviews. However, the aim of this study was to reveal the various ways that faculty members experience teaching IL to first-year students in a range of disciplines at a public research university in the United States.

Overall, these surveys contain rich information and provide a broad picture of IL education in universities. They suggest that both librarians and faculty members at least claim to regard IL as an important component of a university education; however, there is debate about whether faculty, in general, are paying more than “lip service” to a concept that they fail to fully understand. Following Dawes’s (Reference Dawes2019) observation that the teaching of IL is discipline specific, it is useful to see where faculty who teach political science fit into this debate.

…there is debate about whether faculty, in general, are paying more than “lip service” to a concept that they fail to fully understand. Following Dawes’s (Reference Dawes2019) observation that the teaching of IL is discipline specific, it is useful to see where faculty who teach political science fit into this debate.

INFORMATION LITERACY AND POLITICAL SCIENCE

There is no extensive literature regarding the teaching of IL in political science. However, a good proportion of the literature that does exist explores the relationship between librarians and political science faculty (e.g., Harden and Harden Reference Harden and Harden2020; Shannon and Shannon Reference Shannon and Shannon2016; Stevens and Campbell Reference Stevens and Campbell2008; Thornton Reference Thornton2006, Reference Thornton2008). This literature contains the same themes as the broader IL literature. Specifically, it argues that IL skills are critical for students who are attempting to navigate the political world. Harden and Harden (Reference Harden and Harden2020, 345) go as far as to argue that “teaching IL is perhaps even more important for political science faculty compared to other disciplines.” The literature also suggests that political science students tend to arrive at college lacking the necessary IL skills. They often are not aware of this lacuna; faculty members, however, are aware of their students’ shortcomings (Shannon and Shannon Reference Shannon and Shannon2016, 458). Nevertheless, there is consensus that faculty do not sufficiently address the problem. The main differences within the literature are concerned with how best to improve this situation.

In much of the literature, greater collaboration with the university library is the way forward. For example, according to Shannon and Shannon (Reference Shannon and Shannon2016, 459–60), the best way to solve the IL problem in the political science classroom is to develop the idea of “embedded librarianship.” That is, the increased use of information specialists in the classroom is needed to facilitate IL such that welcoming the librarian becomes routine. Furthermore, if resources are limited, it is suggested that the academic department and the library staff design a strategy to maximize the impact of the library, especially in the first year of college (Shannon and Shannon Reference Shannon and Shannon2016, 466).

The other side of the debate is represented by Harden and Harden (Reference Harden and Harden2020). They contend that although this embedded approach can be useful, it also may discourage faculty from teaching IL. They explained that relying on the librarian to teach these skills has potentially prohibitive startup costs and that this type of arrangement can imply that only librarians can teach IL. Instead of relying on the library staff, faculty instead should implement a series of IL activities throughout their courses. In this line of thinking, faculty members fail to teach IL not because they do not value it but rather because they wrongly believe it can be obtained passively. Once faculty members are made aware of the importance of IL, they will want to teach it in their courses.

To summarize, both schools of thought represented by Shannon and Shannon (Reference Shannon and Shannon2016) and Harden and Harden (Reference Harden and Harden2020) suggest that students need help in developing IL skills to become effective graduates of political science but that faculty currently do not make a sufficient effort in this regard. As articulated by Fister (Reference Fister2021), there is a sense that no one claims responsibility for IL in the political science classroom. The difference is that Shannon and Shannon (Reference Shannon and Shannon2016)—in line with McGuinness (Reference McGuinness2006) and DaCosta (Reference DaCosta2010)—do not have much faith in the willingness and enthusiasm of faculty to take IL sufficiently seriously. Thus, they want to center IL education around the known information expert (i.e., the librarian), whereas Harden and Harden (Reference Harden and Harden2020)—like Bury (Reference Bury2016) and Dawes (Reference Dawes2019)—have a more optimistic perception of faculty, suggesting that they can take greater responsibility for future IL education. To discern which is the best path, our research adds to the literature something that thus far is missing: a comprehensive survey of political science faculty attitudes toward IL education.

THE SURVEY

To examine opinions about students’ IL skills as well as how prevalent IL instruction is within the first-year classroom, we sent a survey asking a series of questions concerning these topics to 2,983 political science faculty members at universities worldwide.Footnote 1 We received 101 responses, of which 80 respondents had recently taught a first-year political science course; they were asked to continue the survey.

A breakdown of these responses shows that 45 respondents taught in the United States, 27 in the United Kingdom, four in Australia, two in Canada, one in Singapore, and one in Sweden. Furthermore, 37 respondents conducted research in comparative politics or area studies, 35 in international relations, two in political theory, and six in the “other” category (i.e., public policy and administration). Four postdoctoral scholars, 17 lecturers/assistant professors, 23 associate professor/senior lecturers, three readers, and 23 professors responded to the survey (Thornton and Atkinson Reference Thornton, Atkinson, Williams and Evans2022).

QUESTIONS ABOUT STUDENTS

The responses to our questions about faculty members’ perceptions of their students’ IL were illuminating. Figure 1 presents answers to a question about whether respondents agreed with the statement that students arrive at university with sufficient IL to successfully construct a competent research paper. Of all respondents, 55% disagreed and 26.3% strongly disagreed with this statement. These findings confirmed previous surveys reporting that faculty members do not believe students arrive on campus with sufficient IL to be successful university students.Footnote 2

Figure 1 Faculty Perceptions of Whether Students Arrive with Sufficient IL to Succeed

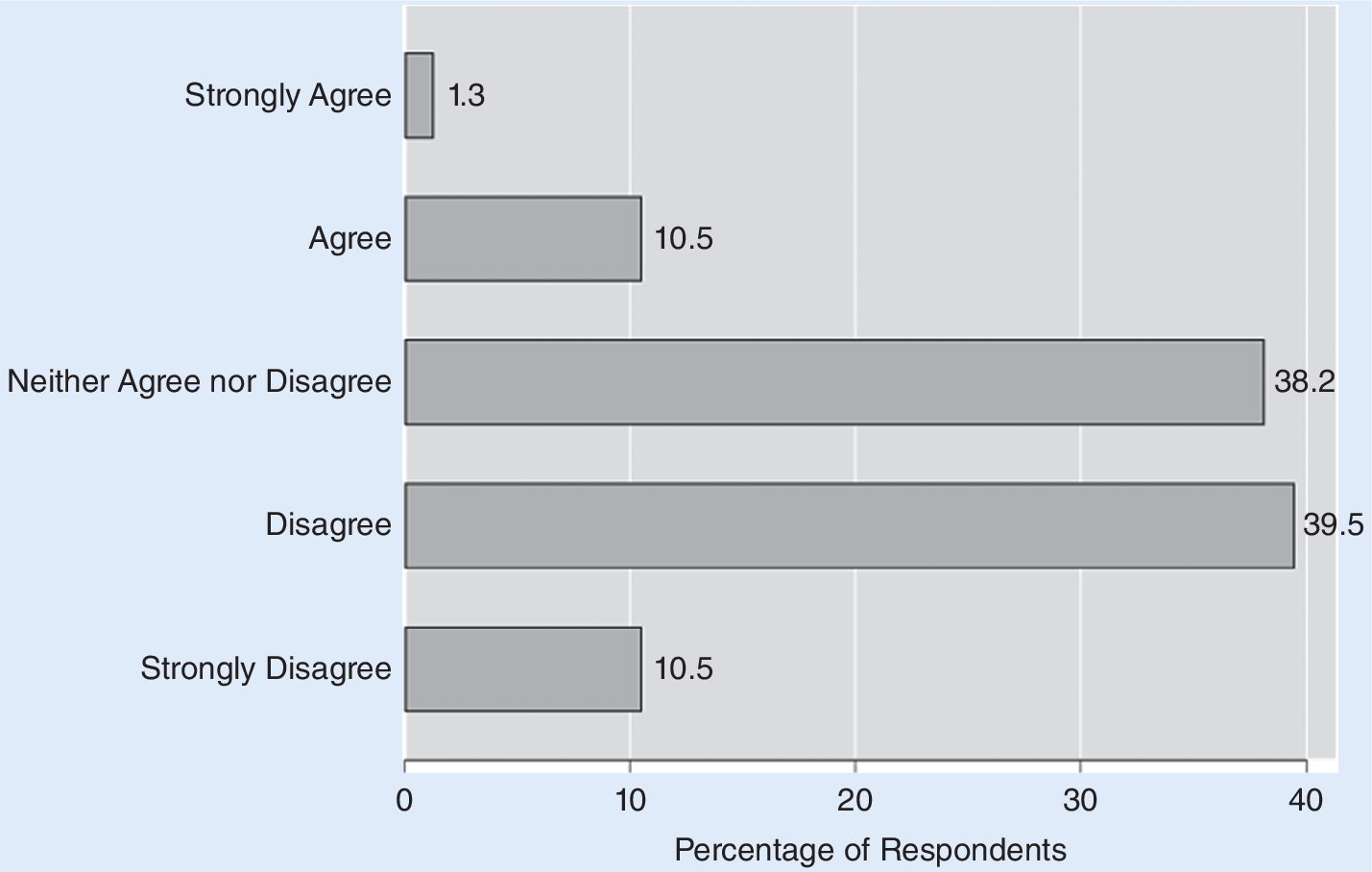

We also wanted to see whether faculty members thought that their students’ IL had changed over time (figure 2). We asked respondents if they agreed with the statement that the standard of IL of students entering university was better than it was five years ago.Footnote 3 Of all respondents, 39.2% stated that they neither agreed nor disagreed with this statement, 30.5% disagreed, and 10.5% strongly disagreed. Overall, we found that 80.2% of respondents did not believe that students were more competent in IL in an academic setting than they were five years ago.

Figure 2 Faculty Perceptions of Whether Students’ IL Abilities Have Declined

QUESTIONS ABOUT THE FACULTY

Our results thus far suggest that first-year political science faculty believe IL to be important and that students’ IL competencies are not improving. We also wanted to know what faculty members are doing to help their students. We first asked them whether the courses they teach have at least one session explicitly dedicated to IL (figure 3, upper-left panel). We found that 56.3% of respondents stated that they do not provide IL training in the classroom and only 43.8% do.

Figure 3 Faculty’s Classroom Behavior

We then asked respondents whether they had invited a librarian into their classes to provide IL training (see figure 3, upper-right panel). We found that 72.5% of respondents did not and 27.5% did. Finally, we asked whether the university where they work provides IL training for students. Of all respondents, 37% answered no and 62.8% answered yes.

The larger picture gleaned from this series of survey questions shows that whereas many faculty members believe IL is important, less than half of survey respondents are implementing IL education in their classroom.

We then analyzed what makes faculty members more or less likely to implement IL. We anticipated that having specific IL training would make them more likely to expose their students to IL. We asked respondents whether they ever participated in IL training: 53.8% stated no and 46.3% stated yes (figure 4). There is a concern that “IL training” could include a chat with a librarian and participation in an assessed module, but we were most interested to discover simply whether faculty members believed that they had experienced training rather than to explore the nature of that training. This concern can be the subject of future research.

Figure 4 Faculty Received IL Training

To assess the effect that faculty members receiving their own training has on IL instruction, we performed a series of logistic regressions. In the first logistic regression, we assessed whether those who received IL training made them more likely to implement it in their own courses. Our dependent variable was taken from a question in which we asked respondents if they conducted at least one class session dedicated to IL. In addition to using the training question as an independent variable, we included demographic information (i.e., rank, subfield, and gender) as controls. Figure 5 provides the predicted probabilities for the effects of training on the probability of at least one class session dedicated to IL.Footnote 4

Figure 5 Logistic Regression on IL Instruction

As shown in figure 6 (left-hand panel), when faculty members received IL training, it considerably increased the probability that they include IL in their own courses. We found that a faculty member who did not have IL training had a 0.32 probability of conducting at least one course dedicated to IL. Conversely, one who did have IL training had a 0.56 probability of conducting an IL session. This is a significant change in probability of 0.24 point, suggesting that IL training (at least in a form that a faculty member recognizes as IL training) positively affects their behavior.

Figure 6 Faculty’s Confidence in Their Own IL Abilities

We also wanted to assess the effect of faculty members who had IL training on their likelihood of inviting a librarian into their class. We found that having IL training had a significant effect (see figure 5, right-hand panel). A faculty member with no IL training had a 0.17 probability of inviting a librarian whereas one with IL training had a 0.36 probability. This is a change in probabilities of 0.19 point. These findings, along with the previous analysis, suggest that when faculty members have IL training themselves, they are much more likely to ensure that their students receive it.

Finally, we assessed whether having IL training affected faculty members’ confidence in their own abilities. For our dependent variable, we used responses to a question in which respondents were asked to rate their IL abilities on a 5-point scale.Footnote 5 Because our dependent variable is ordinal, we used an ordinal logistic regression. Our main independent variable was whether a faculty member had IL training, and we used the same controls as the previous analysis.

Figure 6 shows that having IL training increased faculty members’ confidence in their own skills.Footnote 6 When they did not receive IL training, there was a 0.34 probability that they were very confident in their IL skills. Conversely, when they had received IL training, they had a 0.55 probability of being very confident—a change of 0.21 point in the probability that they will be very confident. These findings suggest that not only does IL training positively change the probability of faculty implementing training in their own courses; it also positively affects the confidence that they have in their own IL abilities. It is obvious, however, that the results do not indicate whether that confidence is merited.

CONCLUSION

Our findings confirm that many political science faculty members understand that there is a problem with students’ IL. They also show that perception of this problem is certainly not diminishing, which aligns with the findings of similar surveys. Our results also show that although there is widespread awareness by faculty of the problem, it does not automatically translate into action in the political science classroom. This finding concurs with the McGuinness (Reference McGuinness2006), DaCosta (Reference DaCosta2010), and Shannon and Shannon (Reference Shannon and Shannon2016) arguments that although faculty claim to be concerned about IL, their priorities ultimately lie elsewhere and librarians need a more powerful role. However, our survey also suggests that there is hope for the aspirations of Bury (Reference Bury2016), Dawes (Reference Dawes2019), and Harden and Harden (Reference Harden and Harden2020) that faculty can be motivated into action. Apparently, IL training for faculty members can provide this important encouragement.

In a more broad reflection, it may be that what matters is not the identity of who takes charge of making IL an important component of the political science education. What matters is simply that somebody does, and that this vital part of the twenty-first-century university curriculum does not, as Fister (Reference Fister2021) warned, remain hopelessly located both everywhere and nowhere. The alternative is bleak: if students of political science cannot cultivate a critical relationship with information, what hope is there for the rest of society?

…it may be that what matters is not the identity of who takes charge of making IL an important component of the political science education. What matters is simply that somebody does.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science and Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LNTRMB.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096522000397.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.