Curriculum assessment, despite its benefits, often is neglected or actively avoided in academia (Cole and De Maio 2009; Smoller Reference Smoller2004). Some political science and government departments, however, recently made major changes to their undergraduate curricula in the wake of internal assessments. Stanford University and Duke University, for example, shifted from “traditional” subfields such as American government and comparative politics to more issue-focused fields such as “Elections, Representation, and Governance” and “Political Behavior and Identities.” These universities are witnessing a coinciding increase in the number of students enrolling as undergraduate majors.

The assessment reported on in this article, undertaken at Georgetown University, addressed a unique “problem”: the diversity of our students and the popularity of our field—which typically includes 500 to 600 majors at any given time—taxes our faculty and graduate student resources. In this respect, Georgetown may be atypical nationwide (Kelly and Klunk Reference Kelly and Klunk2003). Its location in Washington, DC, and its well-known Department of Government and School of Foreign Service mean that many students choose the university precisely because they are interested in politics or want to work in the public sector, and they expect to be trained accordingly. As a result, nearly one thousand students take at least one of the four introductory classes offered in our department each year.

Therefore, we conducted our curriculum assessment with two goals: (1) understanding the extent to which the curriculum lives up to brochure promises (i.e., equipping students with adequate knowledge of the discipline, necessary skills for their future careers, and valuable experiences for their lives as engaged citizens); and (2) optimally deploying our faculty resources. That is, our curriculum assessment was not focused solely on attracting students, achieving narrowly defined learning outcomes, or appeasing external accreditors (Ishiyama and Breuning Reference Ishiyama and Breuning2008). Rather, it was a wide-ranging assessment intended to be used to retool the undergraduate curriculum and to ensure that faculty–student interactions allow for the most meaningful types of contact and learning. The lessons learned from this assessment are especially relevant for similarly large departments, but we hope that they will also be informative to departments of various sizes and specialties. In particular, our inquiry highlights important questions about the evolving roles played by key elements of the discipline and curriculum, ranging from subfields to methodology and from ethics to writing and other communication skills.

HOW WE ASSESSED OUR CURRICULUM

The undergraduate major in government at Georgetown University is designed to provide a solid grounding in the major subfields of political science and to allow a deeper, yet flexible and student-interest-driven engagement of one or more subfields. It consists of 10 courses, including four introductory courses spanning the traditional subfields of political theory, comparative government, American government, and international relations. Students also take a series of six electives, which must include at least one additional course in political theory and one writing-intensive departmental seminar. In addition, we currently offer a two-course sequence in quantitative methods, which reflects general agreement among the faculty that undergraduates should have the opportunity to take these classes. Neither course is required, however, and whether to offer other methods courses at the undergraduate level is the subject of ongoing discussion.

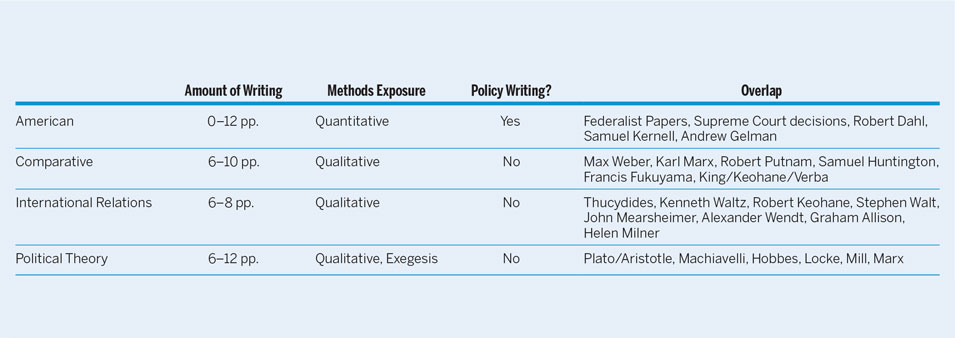

To assess the effectiveness of this curriculum, we performed three primary tasks. First, we developed a curriculum map that identified basic patterns in our teaching (Plaza et al. Reference Plaza, Draugalis, Slack, Skrepnek and Sauer2007; Uchiyama and Radin 2009). This entailed an examination of available syllabi for courses offered from 2011 onward. We focused primarily on introductory courses because every government major takes those courses and because multiple instructors teach them due to high demand. However, we also examined all of our upper-division courses to better understand a student’s trajectory through the major. In developing the curriculum map, we reviewed each instructor’s syllabus for a given course to determine, among other things, how much weekly reading was assigned on average, what type of graded assignments were given, the length of any assigned papers, and whether students were exposed to any methodological tools. A detailed curriculum map was distilled into “snapshots” of the undergraduate curriculum. One snapshot, shown in table 1, demonstrates how introductory courses were coded. (Caveat: this is a simplified format that cannot fully account for variation among professors who teach the courses.)

The existing curriculum consists of 10 courses, including four introductory courses spanning the traditional subfields of political theory, comparative government, American government, and international relations. Students also take a series of six electives, which must include at least one additional course in political theory and one writing-intensive departmental seminar.

Table 1 Curriculum Map: Introductory Course Snapshot

Note: The amount of writing represents the range across multiple different syllabi for the same course. “Methods exposure” indicates the type of method emphasized most in these courses, which happens primarily through assigned readings. “Overlap” indicates authors or pieces that are used in at least three different introductory courses. Plato and Aristotle make a combined appearance under political theory because one or the other is typically assigned within the context of lectures that cover both thinkers.

Second, the curriculum map provided a better understanding of our own curriculum and the types of skills that students acquire at each level. However, it could not provide a sense of how undergraduates subjectively experienced the curriculum—whether they could avoid writing papers in most of their classes, for example, or the extant subfields were useful to them. For this reason, we hosted a series of focus groups with current undergraduates (i.e., primarily juniors and seniors with at least five government courses already completed) and alumni (i.e., class of 2011 or more recent). The six focus groups—three for current students and three for alumni—each consisted of 10 or fewer individuals, all of whom participated on condition of anonymity, and were led by a facilitator from outside of the department (Morgan Reference Morgan1996). Footnote 1

Third, after developing the curriculum map and conducting focus groups, we surveyed all current students and recent alumni, which is a common strategy used in similar departmental assessments (Deardorff and Folger Reference Deardorff and Folger2005). The curriculum map provided an initial set of questions to ask, and the focus groups allowed us to test and refine those initial questions before fielding the larger survey. The survey, which received 208 responses, allowed us to ask finely tailored questions of a broader audience.

FIVE THINGS WE LEARNED FROM OUR CURRICULUM ASSESSMENT

Although there are a variety of potential benefits to curriculum assessment—better undergraduate education, better student performance, and a more attractive department for prospective students, among others (Deardorff and Posler Reference Deardorff and Posler2005)—we discerned at least five general lessons from our semester-long effort.

-

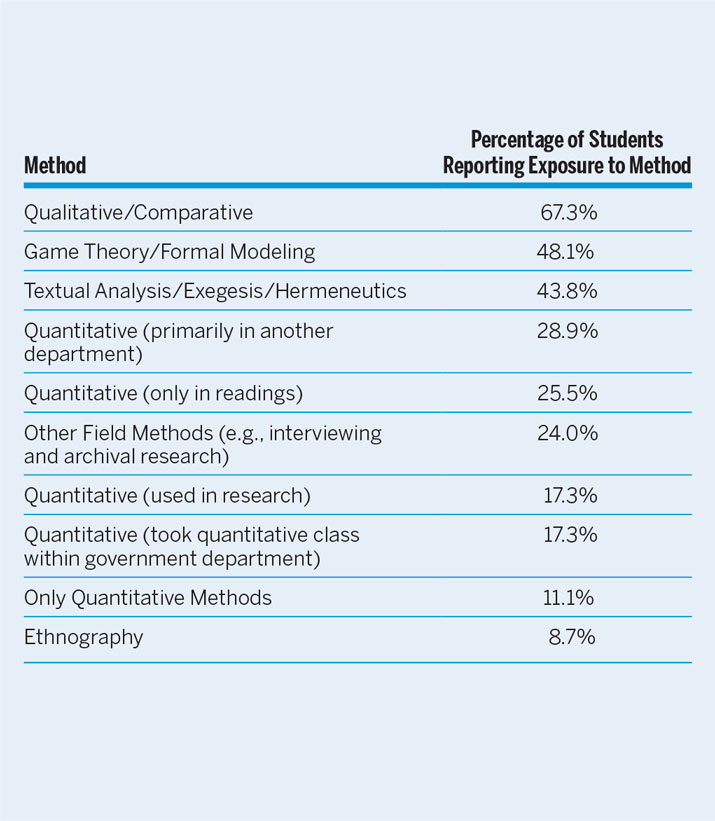

1. Methods matter. Many students enter the department with no desire to study quantitative methods—or even an awareness of how widespread these methods have become in the social sciences—but they often wish they had studied them by the time they graduate. Indeed, many current undergraduates expressed a desire to avoid dealing with quantitative methods. Some suggested that they chose the government major rather than a similar major in the School of Foreign Service because government would not require a course in economics. However, several current students and many alumni in the focus groups expressed that they wished the importance of quantitative methods had been impressed on them sooner. When methods training was first brought up in one alumni focus group, an immediate response was, “For the love of God, we need more data analysis.” Footnote 2 Moreover, the survey indicated that our alumni hold positions in a wide variety of private and public enterprises; that so many emphasized the need for quantitative training suggests that this is a broadly felt need. Table 2 indicates survey responses to the question, “To which methods were you exposed?” Many were exposed passively to quantitative methods in one way or another, but relatively few students appear to have actively used them. The same likely is true of other methods listed in table 2.

-

2. Writing must bridge the gap. A key interest when beginning this assessment was the nature of writing in the department. We learned that students think we do a good job of developing their writing skills—nearly 77% of those surveyed agreed that the department improved their writing skills, whereas only about 12% disagreed. Footnote 3 Students in our focus groups evinced an awareness and appreciation of this as well. One current student emphasized that quality writing is just as marketable as expertise in research methods or other technical skills. Footnote 4 Moreover, most students are exposed to various types of writing. Of those surveyed, 92% answered that they were required to write a research paper at least once, and slightly more than 60% had written a policy paper or memo. We also learned that the average paper length increases over time, as it should: about 12% of papers assigned within the first two years exceeded 10 pages, which increased to 47% in the last two years.

There are systematic differences in the type and length of writing required across subfields: American government makes the most frequent use of brief policy memos, whereas lengthy exegetical writing most often takes place in political theory. Beyond this, there is apparently great variety within subfields, even in introductory courses. Importantly, we noticed a significant gap between the writing of mid-length papers (i.e., approximately 10 pages) and long papers (i.e., 20 or more pages) or theses. Students often undertook only one long paper during their undergraduate career, frequently in their final two semesters, and some reported being unprepared for this effort. We believe the curriculum may need to construct a better “bridge” from short to long papers.

-

3. Ethics takes effort. We also wanted to learn about the perceived place of ethics in our curriculum—an element we consider an important feature of an education in government, particularly given Georgetown’s Jesuit identity and emphasis on the development of future leaders. Whereas relatively few survey respondents (i.e., about 42%) agreed that ethics was a prominent part of the major, they strongly agreed that it figured most prominently in political theory. Survey respondents, for example, noted that political theory helped them to think about their “role as a citizen,” their “civic duty,” how they “fit into the polity,” the “responsibilities of governments,” and the “philosophical underpinnings” of political systems. Footnote 5 When asked to indicate which subfields gave ethics a prominent role, 145 of the 208 respondents (i.e., about 70%) selected political theory; only 73 respondents (i.e., 35%) said the same of international relations, the runner-up. Comparative government and American Government both fell below 20%.

These results are perhaps to be expected, but it remains an important and interesting finding. As Sartori (2004, 786) wrote, if the task of political science is to generate knowledge of political behavior, then political scientist must be able to answer the question: “Knowledge for what?” It seems that our students believe political theory best answers this question, which should give pause to those who would reduce the resources their departments dedicate to political theory. If we are training individuals who aim to spend much of their professional life seriously engaged in public affairs, we presumably want them to reflect on their own ethical commitments, as well as the values implicit in their preferred policies.

-

4. Students are interested in subfields with market value. As noted previously, our curriculum assessment was partly inspired by similar appraisals and subsequent changes made to curricula at other universities. We therefore asked students if they preferred extant subfields in the department or the type of subfields created elsewhere (without mentioning other universities by name). In the question, we included three examples of new subfields, including “Political Behavior and Identities,” “Political Institutions,” and “Justice and Law.” The responses were ambivalent. About 26% (i.e., 54 respondents) said they would like such a change; 20% (i.e., 42 respondents) said they would not. A plurality of the respondents (i.e., 46%) said they would need more information. Current students and alumni generally agreed, however, that what mattered most was having a meaningful signal of their specialization—perhaps, for example, a notation on their transcript. Several current students noted that the extant subfields work well for them; the only problem is that they do not translate into a formal specialty. Footnote 6 More than any particular assortment of subfields within the department, students want recognition of their focus. As a corollary to this, they want subfields to be descriptive and focused enough that prospective employers will know what any given subfield is.

If the task of political science is to generate knowledge of political behavior, then political scientist must be able to answer the question: “Knowledge for what?” It seems that our students believe political theory best answers this question, which should give pause to those who would reduce the resources their departments dedicate to political theory.

-

5. Alumni speak from the “real world.” Finally, we learned how useful it is to include both current students and alumni in curriculum assessment. For example, we learned from current students that they initially avoided and subsequently came to recognize their need for quantitative work. Alumni told us more directly what type of methods training would be most useful to future graduates. Moreover, reaching out to both groups demonstrated the department’s ongoing commitment to engagement with undergraduates. The large size of the department can be intimidating for some students; therefore, the focus groups and surveys were perceived by many respondents as a welcome opportunity to provide direct feedback. Even if we do not change the undergraduate curriculum, many simply wanted to feel that they were heard (Hill Reference Hill2005).

Table 2 Self-Reported Exposure to Methods

Note: Numbers are based on a survey sent to current undergraduates and recent alumni (i.e., class of 2011 or more recent) of Georgetown University; 208 individuals responded. The survey asked separately about student exposure to quantitative methods (with several options for varying degrees of exposure) and to other methods. Percentages total more than 100% because respondents could select more than one response.

THREE THINGS WE STILL WONDER

Although our curriculum assessment was helpful, we continue to grapple with three questions.

-

1. Which methods, and how? First, although we learned that many students want to receive more exposure to quantitative methods, we continue to ponder the best way to teach methods and research design to undergraduates. Our department currently offers two quantitative-methods classes for undergraduates that mirror our graduate methods sequence. Our undergraduates suggested that they might need a different kind of preparation. Some mentioned the need for basic data-cleaning and data-visualization skills, whereas others wanted to learn how to read and make sense of quantitatively oriented journal articles without necessarily learning how to conduct their own tests.

We need to answer two questions. First, should a quantitative-methods class be required? This is no small issue because one course is 10% of the major curriculum; therefore, it remains the subject of ongoing debate in our department. Second, even though many of our alumni explicitly stated their desire for more quantitative-methods training, to what extent do we need to ensure that students are exposed to other methods and—perhaps more important—to the fundamentals of research design and epistemology? As indicated in table 2, many students were exposed to qualitative or interpretive methods of some type; however, about 11% said they were exposed only to quantitative methods. Even if we can improve our quantitative-methods training for undergraduates, should we stop there? Moreover, does our students’ tendency to equate “methods” with quantitative methods suggest that, indeed, we should start with a course that introduces students to various methods, their respective costs and benefits, and their ontological assumptions?

-

2. Making ethics visible across the curriculum. Second, we still wonder how best to bring ethical questions into the classroom or how to show students that ethics is part of the conversation—even when Plato’s conception of justice is not the subject of that day’s discussion. It may be that it is simply difficult for students to perceive normatively loaded material as “ethics” unless it is presented as such. (This may reflect a broader limitation of an assessment that asks students to understand and use technical language about their education.) Footnote 7 Nevertheless, there likely is some truth to their observation that ethics is discussed most often in political theory and less frequently in other subfields. The focus there, at least in terms of graded assignments, often is on learning about particular facts or theories and demonstrating an understanding of them. International-relations classes may touch on just war theory or international law, for example, but students may have less opportunity (and/or perceive less reward) in debating competing normative viewpoints in these classes. The desire to avoid contentious conversations also may lead students to avoid debates about the ethical obligations and tradeoffs that might come with the task of steering a nation’s foreign policy. How to more clearly foreground these ethical concerns remains an open question. One possible answer—the addition of a form of community engagement to the curriculum—would be desirable and feasible given our location, but this also would further strain faculty resources.

-

3. Skills for service. Third, what are the best ways to integrate speaking and presentation skills? Many current students say they desire these skills. Alumni affirm that they use oral-communication skills most in their professional life. Combined with the fact that only 55% agree that the department improved those skills (46% “somewhat” agree; 9% “strongly” agree), this may explain why relatively few (i.e., 16.4%) state the major prepared them “very well” for what they are doing now. Footnote 8 One way to improve oral-communication skills could be to make senior-year, integrative, and capstone projects more widely available and to include an extended presentation. Our department currently offers few avenues for these projects, and most take the form of a senior thesis available only to those who are in the honors program as well as on campus for their final three semesters. We hesitate to require such a project of all government majors (although this may be feasible in smaller departments) in part because other majors and minors require their own integrative project. Given that many of our students choose to double major (including 88 of the 208 survey respondents), we are sensitive to the concern that they may have to work on several large projects simultaneously. That said, we clearly need to give students more opportunities to conduct and present original research. Extant discussion sections appended to introductory courses, small department seminars, and occasional in-class presentations may not be sufficient.

CONCLUSION

We learned much from our curriculum assessment. The five lessons outlined here are simply those most readily apparent and, we believe, most likely to reflect the needs of students in departments that otherwise may not look like ours. These lessons come with caveats, of course. We learned that many undergraduates want more exposure to quantitative methods and that these courses do not need to mirror their graduate equivalents. However, it remains unclear how we can best serve the greatest number of undergraduates without asking instructors to teach increasingly varied methods courses. We learned that undergraduates are not concerned about what we call our subfields as long as their specialty receives acknowledgment. However, we remain agnostic on the question of whether traditional or newer subfields can best address our pedagogical goals as well as our students’ professional concerns. Finally, we recognize the long-term challenges facing curricular reform, including that of educating accreditors who must be made aware of these changes and who may need to devise new metrics for evaluating the success of any reforms.

Although our curriculum assessment yielded several unanswered questions, we can now engage those questions more productively because of the information it elicited. Moving forward, we are even more convinced that homogenizing reforms would not be appropriate for our large, diverse student body. Rather, we learned that we would do well to focus on improving core aspects of our program—including writing, methods, and ethics—that encompass subfields and courses. By doing so, we can better convey the richness of our discipline and prepare our students for a lifetime of work, service, and meaning.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517001901.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Charles King, Randy Bass, Lara Bryfonski, Samantha Levine, Erika Bullock, Jacob Arkatov, Camille Balleza, and two anonymous reviewers for their support and feedback. We also thank the Georgetown University Writing Center for partially funding the curriculum assessment, as well as the Georgetown students and alumni who participated in focus groups and surveys. The Georgetown University Institutional Review Board ID number for this study is 2016-0301.