Introduction

It has often been observed that when national governments reduce their central role and devolve public service provision to intermediary organisations, centrally determined monitoring and regulation increase (Rhodes, Reference Rhodes2000; Light, Reference Light2001). An illustration of this is the English National Health Service (NHS), which has seen both a reduction in the number of hierarchical levels and an increase in the number of regulatory and monitoring mechanisms (Walshe, Reference Walshe2002). Many of the latter mechanisms are external to health care organisations, but others, such as clinical governance, are carried out internally. In the case of primary care organisations (PCOs) in England and Wales, clinical governance should be understood as both internal and external: internal to PCOs themselves and external to the small businesses that are operated by independent contractors within PCOs.

PCOs (primary care trusts (PCTs) in England and Local Health Boards (LHBs) in Wales) are statutory public sector organisations responsible for purchasing or providing almost all health care for their populations. Within them, independent contractors (general practitioners (GPs), dentists, optometrists and pharmacists) provide most primary health care. They are both part of and distinct from the PCO. Independent contractors do not wish to be managed, hence their choice of independence. Yet PCOs are expected to guide and direct the development and quality of primary care, though they lack the management tools to do so directly. They rely instead on the terms of the contracts, which they administer on behalf of the government, and persuasion.

Independent contractors thus have an ambivalent status, a fact that causes some tension. The introduction of clinical governance, for example, represents either ‘interference’ in or ‘improvement’ of primary care, depending on one’s point of view. It attracted considerable academic attention (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Sheaff, Sibbald, Marshall, Pickard, Gask, Halliwell, Rogers and Roland2002; Sheaff et al., Reference Sheaff, Rogers, Pickard, Marshall, Campbell, Sibbald, Halliwell and Roland2003a; Degeling et al., Reference Degeling, Maxwell and Iedema2004; Flynn, Reference Flynn2004), not least because GPs did not necessarily see clinical governance as supportive or constructive (Gray, Reference Gray2004). There had long been a wariness among some GPs of mechanisms such as audit that

sought to turn medical practice from an individualised, subtle art into an unthinking, routine activity based largely on guidelines and rules

(Black and Thompson, Reference Black and Thompson1993, p 851).Nevertheless, even sceptical GPs had little choice but to accept the principle of clinical governance, partly because it was seen as inevitable and non-negotiable, and partly because improving the quality of care is too self-evidently a ‘good thing’ for it to be possible to argue against it in principle. Other GPs had long been committed to improving the quality of care by audit, the development of group practices and multi-disciplinary teams, and the provision of professional training and education, and they viewed the policy direction much more positively.

In common with other quality initiatives, clinical governance concerns both quality improvement (QI) and quality assurance (QA) (Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Sheaff, Sibbald, Marshall, Pickard, Gask, Halliwell, Rogers and Roland2002)): QI mechanisms support clinicians and their teams in improving their own practice, while QA mechanisms detect and tackle poor performance. There may be tensions between these different functions (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Sheaff, Sibbald, Marshall, Pickard, Gask, Halliwell, Rogers and Roland2002), and Roland and Smith (Reference Roland and Smith2003) noted that PCOs appeared to find QI easier than QA.

In 2004, a new GP contract introduced a further quality mechanism in the form of the quality and outcomes framework (QOF). This rewards GPs for meeting a large number of very specific targets relating to service quality. Structurally, the QOF is very different from clinical governance, as it is embodied in the GP contract, to which all GPs must attend in order to receive income, rather than in the processes of the PCO, with which GPs may choose not to engage (Wilkin et al., 2002; Degeling et al., Reference Degeling, Maxwell and Iedema2004).

This paper draws on a study of the governance mechanisms relating to quality in primary care in England and Wales since 1991. It describes three different models of how PCOs have tackled QI and QA and discusses these in relation to the well-known organisational typology of hierarchy/market/network. The paper does not include the other categories of independent contractor (dentists, optometrists and pharmacists) as no individuals from these groups were interviewed. Nor does it consider practice-based commissioning, an innovation in England that may be seen as a market-style quality mechanism, although the primary focus is on services other than those already provided in primary care. This was not fully established at the time of data-gathering, and was therefore excluded, as data would be provisional and speculative.

Methods

The study draws on three qualitative case studies of PCOs, which looked at a wide range of aspects of governance and quality: for example, the role of boards and professional executive committees, the commissioning process, and patient and public involvement. Other findings will be reported elsewhere.

The case studies were based on semistructured interviews with key personnel (officers, clinicians, board members) in two PCTs and one LHB. PCT1 serves a London borough with a total population of about 300 000 including considerable socioeconomic and ethnic diversity. PCT2 serves two out of the three towns in a borough on the edge of a metropolitan area in northern England, with a population of about 78 000, deprived and almost exclusively white British. LHB1 serves a prosperous rural and country town population of about 93 000 (largely white British) in Wales. The strategy for choosing case study sites was to represent a diversity of organisational size, location and demographic characteristics. Recruiting sites proved difficult, so the sample is less varied than intended, and over-represents small PCOs.

Informants were selected as follows. Chief executives were approached in the first instance; they were asked to agree to be interviewed themselves, and to nominate colleagues. Attempts were made to interview at each site officers, directors, board members and independent practitioners and their staff.

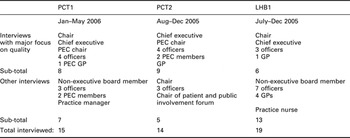

Interviews took place in summer/autumn 2005 (LHB1 and PCT2) and late winter/spring 2006 (PCT2). They included a variety of questions about the structure and functions of primary care, both currently and since 1991 (see Box 1). It was the intention that informants would be given the freedom to expand on those parts of this extensive topic guide that most interested them. Table 1 lists that proportion of interviewees (23/48) who discussed at any length the issues that are the subject of this paper. This paper draws on the data gained from their interviews.

Box 1 Topic guide for interviews

What is your job title and role?

How long have you had this sort of role?

Thinking of each of the areas of commissioning in turn: what are the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and strengths of the PCT/LHB’s governance for quality? Who/what do you see as the key players/drivers?

To what extent are your commissioning objectives determined by national targets?

How does the PCT/LHB prioritise which national targets it will strive hardest to meet?

Have Patient and Public Involvement Forums and Overview and Scrutiny Committees/Community Health Councils influenced PCT/LHB decision-making about primary care, and if so, how?

Do you try to build expertise and capacity in these organisations, and if so, how?

Does your organisation have adequate capacity to commission hospital services, community health care and primary care? If not, which are the winners, which are the losers?

(Where appropriate): Please could you comment on how governance for quality in overseeing primary care has changed throughout the many changes in policy since the early 1990s?

Table 1 Interviewees at the three sites who discussed quality issuesFootnote a

a Clinical governance, QOF, other quality initiatives past and present.

Interviews were taped and transcribed, and analysed thematically using NVivo. Transcripts were repeatedly read, using the constant comparison method, and themes were identified and modified during the process. Conscious efforts were made to identify differences between English and Welsh organisations and between larger and smaller organisations, though these were surprisingly few. Indeed, the final framework of analytic categories reflected those in the original research design, which used the hierarchy/market/network framework with the addition of ‘governance from below’ (patient and public involvement; see Box 2).

Box 2 Analytic framework

Hierarchy Pressure from government

Targets

Boards – membership

Boards – trust or challenge

Directly managed services

Markets

Contracts/service level agreements – effectiveness

Contracts/service level agreements – monitoring

Power balances Hospital reconfigurations

Primary care contracts

GPs – Quality and outcomes framework enhanced services

Dentists

Pharmacists

Networks – external

PCOs

Local government

NHS trusts

Networks – internal

Bureaucrats and clinicians

PEC

Clinical governance

Patient and public involvement

Structures and processes

Consultations

Effectiveness

Ethical approval was obtained from South East Wales Local Research Ethics Committee Panel B (05/WSE02/31).

Findings

Analysis of the data suggested three models for promoting quality, and these are reported separately, in chronological order. However, the three models are in no sense mutually exclusive: for example, clinical governance and QOF coexist in all PCOs.

Model 1

The first model was collegiate, and is well illustrated by the description of a total purchasing pilot recalled by LHB1 informants. Total purchasing was a variant of GP fundholding. GP fundholding allowed participating volunteer GPs to purchase a restricted range of healthcare for their patients: total purchasing allowed participating GPs to purchase, theoretically, the whole range of health care (although in reality this was not attempted (Mays et al., Reference Mays, Wyke, Malbon and Goodwin2001)). In the case of LHB1, the pilot involved all the GPs in the county.

The main thing I think it achieved was bringing the practices together in [county]… I think what we achieved from it was probably getting some clinical networking going. And we did have some actual outcomes in terms of particularly diabetes at that time, outcomes in terms of running a [county] – wide audit… We picked up quite marked discrepancies in the clinical care across the patch, and I think it was peer group pressure was moving towards changing those. Obviously some people didn’t want to change but as a general rule people were interested to see how other practices were performing and what they were doing and what sort of cases they were referring, and there was a debate and discussion as to the way forward. And I think that did lead to an improvement of actual clinical care…

(LHB1, GP3)

This was clearly a mechanism for QI rather than for QA. It involved a ‘bottom-up’ collaboration that was voluntary and spontaneously developed by GPs. The use of audit and peer comparison as QI techniques were adopted by many fundholding practices (Audit Commission, 1996) and other total purchasing pilots (Goodwin et al., Reference Goodwin, Leese, Baxter, Abbott, Malbon and Killoran2001).

The speaker noted that the collegiate model had been maintained in a modified form with the compulsory metamorphosis of the total purchasing pilot into a Local Health Group in 1999. She/he saw this as similar to the total purchasing pilot in that it was primarily a clinical organisation, which had been able to concentrate on the quality of primary care. (It had had little influence on hospital services, having chosen not to put its efforts into an area where it had little power. Local Health Groups advised health authorities on the purchasing of hospital services, but could not themselves directly purchase.) With the compulsory transformation of the Local Health Group into LHB, she/he felt that this clinical focus had been lost: the statutory duties of the LHB dominated the agenda, and the organisation became bureaucratic rather than clinical. This disengaged GPs who had formerly taken a leading role: they cooperated with the LHB without being proactive.

Model 1 had also been evident in one part of PCT1 during the 1990s, when a local Medical Audit Advisory Group had flourished, bringing together a number of diverse practices. This was not described in detail, although the GP who mentioned it said that some of the collegiate relationships then forged were still alive and active in the present, despite the demise of the group itself.

Model 2

The second model was clinical governance, a quality mechanism imposed by central government, which required PCOs to put in place systems for monitoring clinical activity and processes to help prevent poor practice. Tensions between the support and surveillance functions of clinical governance were evident. LHB1 officers emphasised that in maintaining clinical governance systems (as indeed in administering the QOF), they wanted to emphasise QI, but that not all GPs were persuaded.

I went to see a GP yesterday and he said, ‘I understand that you want to work with us, but don’t forget that you police us as well!’ Yes, well, I know that, but we don’t really – you know, we don’t carry the banner for that, because I don’t like to be seen as the police. But obviously they have this view of us…

(LHB1, officer 2)

A colleague acknowledged that the supportive approach was not just a matter of philosophy, but was also more likely to yield results, in the form of GP cooperation. Speaking of the introduction of a clinical risk reporting system, she/he said:

It’s a no blame culture here. And it has to be no blame, because … if we put blame in, we wouldn’t get the forms. And I would rather that someone report to me and it was totally anonymised, so that I could tell everybody else it was happening and to be aware of it, than not be told at all.

(LHB1, officer 1)

Rather than try to manage the tension between QI and QA, PCT1 had sought to defuse it by separating the different functions organisationally. The GP lead on clinical governance had emphasised from the start that clinical governance should

be seen as supportive, that we improve quality through a supportive arrangement.

(PCT1, director)

As a result, clinical governance facilitators were not expected to tackle issues of poor performance. This arrangement may reflect the fact that PCT1 had a higher number of GPs who gave some cause for concern than did the other sites. There was therefore a greater danger in PCT1 that QA processes might eclipse QI, and the separation of QA and QI was able to stop this from happening. Thus, good practitioners could engage in clinical governance without feeling unnecessarily ‘policed’, and less-good practitioners need not feel alienated from clinical governance personnel if there was any ‘top-down’ pressure on them to improve their performance.

Informants at PCT2 described how clinical governance in general had become more bureaucratised. For one GP, it was the growing dominance of the bureaucratic QA process that had disengaged him, by not matching his own interest in QI:

My reason for wanting to be involved was in clinical governance was because of education, was to help GPs to get better and to help nurses to get better, and what have you. But the educational component was quickly squashed out, by the checking and monitoring and appraisals and – all of which have value, but whereas education can be interesting and lively, that tended to be – the dull bits became the important bits.

(PCT2, GP1)

A director acknowledged this shift from QI to QA, seeing it as the result of external requirements.

We were at the point where actually we were getting people to really sign up to it, when we then got bombarded with this kind of view of classic external mechanism, that you know, tries to measure, and it’s measuring the processes… My big issue is the compliance issue with external mechanisms. I have no problem at all in being accountable, being assessed, and we do need to have the right governance arrangements in. But I do feel that over the last couple of years that it has got to overkill. And from my point of view, in a job that has a very broad portfolio, I spend a lot of my time doing things that to satisfy compliance, where I could actually be spending my time more effectively deciding and taking the staff through the change management process, making it better for patients.

(PCT2, director 2)

The imposition of external mechanisms meant that clinical governance was seen by clinicians:

as though it was something that was done to people, rather than it being a state of mind that people need to start to live and breathe and understand around quality

(PCT2, director 2)

And indeed, informants in all three sites suggested that while the spirit of clinical governance ought to be about living and breathing quality, the reality was that the structures and processes that had to be constructed and maintained looked more mechanical than ‘alive’. Those directly involved in clinical governance talked primarily about the processes that had to be created, rather than outcomes: the government’s requirements for clinical governance arrangements appeared to have made this focus inevitable, at this stage. These data appear to confirm Degeling et al.’s (2004) assertion that:

form has dominated substance in clinical governance implementation (p 167).

This may change as arrangements for clinical governance are completed and consolidated.

It should also be pointed out that there were non-contentious aspects of clinical governance that had been successfully embedded in all three organisations: in particular, the local provision of continuing professional education for GPs and their staff. Since such provision was common before the introduction of clinical governance, this was not resented as an hierarchical imposition.

Model 3

The third model was the QOF, that part of the new GP contract that focused on quality. Opinions varied as to whether the QOF was in harmony or contrast with clinical governance. In PCT1, they were regarded as different: the administration of the QOF was kept separate from clinical governance processes. By contrast, a director of PCT2 saw the administration of the QOF as an extension of the work of clinical governance:

We always had mechanisms for constructive debates and dialogue with GPs under the clinical governance format before the QOF. And practice visits, on the basis of talking to practices about how they managed their practice and how they delivered care and what their plans and proposals were for the future, has always been a feature of life in this part of the world anyway. And I see the QOF as a sort of a refinement in a development of those. With the addition, of course, of pretty significant financial incentives.

(PCT2, director 1)

An important difference was that while GPs could refrain from actively engaging in clinical governance, and some did, that was unlikely to be the case with the QOF, not least because there were financial incentives for them to engage. Technically, the QOF was voluntary; but as declining to be judged by it meant a loss of income, there were no reports of non-participation in any of the three sites.

PCO officers saw the potential of the QOF to improve care, though they felt that establishing the requisite processes had not yet yielded the quality dividend they expected in the future. Administering the QOF had helped PCO officers to focus on primary care quality in detail:

it has really enabled us to get out there in primary care and look more at the quality of the services that are being provided against various different indicators.

(PCT2, director 3)

However, increased understanding had not necessarily yet resulted in improved outcomes:

Last year, I would say, the QOF didn’t improve patient care. What it did was it highlighted where patient care needed to be improved, and where it was excellent or good.

(LHB1, officer 1)

The speaker anticipated that improvement would begin to be made subsequently. This view was shared by an officer from PCT1:

What we were able to do this year with QOF is highlight the focus on those practices that hadn’t achieved as much, to work with them as to why, reasons for that. And we’re looking now to use the QOF data in a more constructive way towards long term conditions planning… QOF has also been quite useful in terms of raising the profile of patient experience because there’s quite a lot of points for that.

(PCT1, officer)

A process outcome already apparent was that general practices had put in place staff employment policies, but there was no evidence as yet that these had become operational:

Last year they wrote the policies, and now we want to make sure that they are using them, and that they are working, and if we need to adapt them.

(LHB1, officer 1)

From the point of view of GPs, there were mixed opinions on whether the QOF had made or not made a difference to service quality. One thought that the QOF’s main function was to reward the quality of GPs’ existing practice, rather than to improve care:

By and large, general practices will prove that they can provide quality services, and I think that general practices is a quality service anyway, and the QOF proves that.

(PCT2, GP2)

Others, while disliking the process, acknowledged that it had made a difference:

I thought that ticking the boxes was awful. But I have to say that I think our quality of care, which we thought was quite good, has improved. GPs traditionally – if someone didn’t come for a follow up, you would shrug your shoulders and you know, you would just let them drift off… We weren’t very good, because doctors by their nature aren’t, at routine annual blood tests and things like that. And I have to say, to my amazement, writing and phoning patients: ‘You haven’t come for the appointment, you haven’t come to your annual follow up’, has actually proved very effective.

(LHB1, GP1)

A board member at PCT2 described the impact of the QOF on the achievement of three-star rating for the PCO as a whole:

I think [the QOF] enabled us to get three stars. I do, honestly, I think it’s made the difference. Mostly the smoking cessation …’cos we were struggling with that, you know, we just couldn’t get it. And, I think in some ways the fact that the points system and points meaning pounds, I think that’s quite a useful way of doing things. You know if you can – if you can offer to pay somebody to do something and they do it when you pay them, that’s a fairly direct relationship. It’s a lot easier than trying to win hearts and minds. I’m not saying that’s the best way of doing things, but I would say that with the QOFs – I think it has, it’s helped us and we’ve done well with them. So you know, I’m happy with it.

(PCT2, board member)

Such positive accounts of the QOF’s contribution were the exception rather than the rule. Nevertheless, the tone of discussions about the QOF was noticeably more positive than those about clinical governance. The indicators were acceptable as relevant to primary care, and the linking of achievement with financial reward was in harmony with the nature of reimbursement already familiar to GPs.

Discussion

A number of limitations have already been alluded to. In terms of size, the three PCOs were not representative, since two were unusually small. In any case, it would not be possible for just three sites to be adequately representative of over 300 PCOs in their many aspects. Because of the wide-raging nature of the topic guide, informants were encouraged to choose the topics on which they spoke at length, and a likely consequence of this is that it was those people who found quality issues problematic who chose to discuss them. Thus, their views may not be representative: for example, the fact that five general practice personnel in LHB1 did not speak at length on such issues (see Table 1) suggests a degree of acceptance of the new arrangements not otherwise articulated in this paper.

The three models outlined above may be understood as instance of three different organisational forms: network, hierarchy and market, respectively (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Frances, Levacic and Mitchell1991). The collegiate model of the Total Purchasing pilot (LHB1) can be seen as a network: a voluntary collaboration between small organisations that worked together to achieve common goals while preserving structural independence. Clinical governance is an instance of hierarchy: imposed from above by central government, and requiring bureaucratic administration and the setting of organisation-wide standards, and ultimately the responsibility of the PCO board. The QOF element of the new GP contract used a market mechanism to reward the achievement of quality indicators.

These classifications do not fit perfectly: NHS organisational forms never mirror pure models (Exworthy et al., Reference Exworthy, Powell and Mohan1999). For example, from the general practice point of view, the collection of QOF data, administered by PCO officers, looked rather similar to the administration of clinical governance, and therefore felt very bureaucratic. Nevertheless, the QOF is a market mechanism by virtue of being part of a contract that involves financial incentives and allows service suppliers (GPs) the freedom to opt in or out of that part of the contract.

Another example of an imperfect fit is PCT1’s arrangements for clinical governance which, it could be argued, subvert the typology by using a network (collegiate) approach to keep QI separate from market (QOF) and hierarchy (QA). At one level, this is something of a fudge, a denial that clinical governance is part of what is clearly a government QA agenda. But a degree of evasiveness was accepted by many of those interviewed as necessary: a facilitative rather than a directive style (Marshall et al., 2003) was widely thought in all three sites to be more successful in securing GP engagement, or at least avoiding GP alienation. Because PCOs do not have a full range of direct management techniques to use to shape GP behaviour, they have therefore to use ‘soft leadership’ (Sheaff et al., Reference Sheaff, Rogers, Pickard, Marshall, Campbell, Sibbald, Halliwell and Roland2003a). The tacit agreement between officers and most GPs to avoid alluding to the former’s surveillance functions represents a ‘silent bargain’ or ‘implicit negotiation’ (Strauss, Reference Strauss1978), which facilitates action by avoiding conflict. This negotiation is consistent with the view that senior managers:

are now seen more as agents of government than as facilitators of professionally driven agendas.

(Davies and Harrison, Reference Davies and Harrison2003, p 647)

It also supports Sheaff et al.’s (Reference Sheaff, Schofield, Mannion, Dowling, Marshall and McNally2003b) conclusion that:

priority should be given to maintaining professional values in a bureaucracy. (p 109)

‘Soft-pedalling’ the bureaucratic style can be seen as a useful way in which officers can reduce the perceived threat to professional values.

Inevitably, discussions of contemporary hierarchy involve discussions of bureaucracy because hierarchical organisations are invariably bureaucratic. But bureaucracy is itself a word with a variety of meanings. Lam (Reference Lam2000) (and see Flynn, 2004) provides a useful typology of organisational structure, which sheds light on the nature of bureaucracy in PCOs.

Lam classifies organisations by how knowledge is organised: on the one hand, whether knowledge is explicit and standardised, or tacit and personal; on the other, whether it is held at the organisational level or at the level of individual professionals (see Table 2).

Table 2 Lam’s organizational typology

In the case of knowledge (and activity) relating to quality, GPs have traditionally taken the view that they embody such knowledge, tacitly, and so without the need for organised structures or processes. Black and Thompson (1993) found that doctors resisting the requirement to introduce medical audit systems claimed that they did it anyway. Thus, prior to the introduction of compulsory audit, GPs appear to have defined themselves as the equivalent of an ‘operating adhocracy’. Black and Thompson (1994) observed, however, that in fact this existing activity was spasmodic and disorganised. GPs engaging in a more systematic approach to knowledge and audit, such as occurred in fundholding consortia and total purchasing pilots, may be regarded as working to a model of ‘professional bureaucracy’: it was collective reflection and discussion, rather than organisational systems, that was the crucial process whereby quality issues were addressed, and this was therefore a network model of QI.

There can be little doubt that PCOs, by contrast, are hierarchical, and an example of ‘machine bureaucracy’, standardising knowledge and work at organisational level. Knowledge does not reside primarily in individual professionals, but is collated and scrutinised across the organisation by officers as well as professionals, using standardised systems. Given the duties and structures of PCOs, it is hard to see an alternative to machine bureaucracy. In view of the officer-dominated structure of PCO management, which in its turn is an inevitable result of the statutory functions of PCOs, neither adhocracy nor professional bureaucracy can be sufficient as quality mechanisms, partly because they address QI rather than QA, partly because they are insufficiently systematic.

The codification of governance is at odds with the idea that general practice is simply ‘ineffable’ (Exworthy et al., Reference Exworthy, Wilkinson, McColl, Moore, Roderick, Smith and Gabbay2003), an idea that is very much in keeping with the adhocracy model (‘you can trust us to do the right thing even if we cannot or do not explain ourselves’). The idea of ineffable practice is also clearly incompatible with a culture of evidence-based medicine.

Adhocracy and professional bureaucracy are part of what Moran describes as:

the club-like structure of so much self-regulation in the professions

(Moran, Reference Moran2004, p 32)

But, as he goes on to point out, such club-like structures were:

the institutional epitome of [a] wider system of club government… The destruction of club government in medicine displaced, precisely, a pattern of government through informal networks with fuzzy boundaries and replaced it with something more hierarchical, codified and state-controlled. (pp 35–6)

Thus, at the level of national policy and NHS structure, networks have yielded to hierarchy.

But it is not clear that hierarchy, in the form of machine bureaucracy, will engage GPs sufficiently to enable it to do QI and QA better. Bad practice may be more likely to be noticed and addressed, but the disengagement of good clinicians may result, and our study found evidence of this. In other words, QA may displace QI. The importance of this is likely to be variable. In PCOs where poor practice is a significant problem, prioritising QA may be the best way of improving the standard of care, at any rate in the medium term. But it is unlikely to improve quality in PCOs where the standard of general practice is high.

Certainly, the evidence from this study suggests that a professional bureaucracy is the model with the most potential to harness ‘bottom-up’ aspirations to QI. This model had flourished, and was mourned, in LHB1, while PCT1 had tried to preserve it by maintaining organisational boundaries between QI, QA and the QOF. Whether the network model is sustainable as an anomalous enclave within a hierarchically dominated environment remains to be seen, as do the long-term impacts of replacing professional with machine bureaucracy.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all those who agreed to be interviewed, and to two anonymous reviewers. The study was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, grant number RES-000-22-1198, to which our thanks are due.