Among the surviving narratives of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, the story of the Oglala Lakota spiritual leader Nicholas Black Elk (Heȟáka Sápa) continues to haunt readers with one of the United States’ most infamous moments of settler colonial violence: “The snow drifted deep in the crooked gulch, and it was one long grave of butchered women and children and babies, who had never done any harm and were only trying to run away” (Neihardt 262). Black Elk's memory, alongside the autobiographical accounts of Charles Alexander Eastman (Santee Dakota) and Luther Standing Bear (Oglala Lakota), has helped correct the canonized history of Wounded Knee from what the United States initially deemed a successful battle to, as Standing Bear describes, “a slaughter, a massacre” (224). Survivor stories and US military correspondence collected throughout the first half of the twentieth century have corroborated Standing Bear's, Eastman's, and Black Elk's accounts and have been shared in the form of academic and popular films, documentaries, children's books, articles, and treatises. While this revised history has rightfully undone the dichotomy of civilization and savagery, the primary sources used to do so have tended to be recorded by men, despite the archived reality of Indigenous women who survived, witnessed, and wrote about Wounded Knee. Such historiographic sidestepping of Indigenous women has resulted in a discourse that, though critical of settler colonial agendas, has too often focused on frontier violence and Indigenous death rather than on the resilience and sustainability of Indigenous relations.

In order to analyze the contemporaneous perspectives of Indigenous women alongside the storied survivance of Indigenous men,Footnote 1 scholars of nineteenth-century Indigenous women's writing have focused largely on three writers: the Ojibwe poet Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Bamewawagezhikaquay), the Northern Paiute lecturer and reporter Sarah Winnemucca (Thocmentony), and the Mvskoke Creek novelist Sophia Alice Callahan.Footnote 2 Of these three, Callahan was the only writer still living at the time of the massacre. In fact, she is often remembered as the first Indigenous writer—and the first woman—to publish about Wounded Knee. However, Callahan's inclusion of the massacre in her 1891 novel, Wynema: A Child of the Forest, has been read, like accounts by her female contemporaries, largely within the framework of nineteenth-century sentimentalism (Windell 260).Footnote 3

Complicating the reception of Callahan in current scholarship, Lisa Tatonetti shifts readers’ attention away from a sentimentalist reading of Wynema to focus instead on how Callahan challenges the national narrative of Indigenous depravity by centralizing the role of Indigenous women and sympathizing with the Ghost Dancers at Wounded Knee. At the same time, Tatonetti suggests that “Callahan's depictions . . . demonstrate not just her outrage and fear over the events at Pine Ridge, but also her struggle to imagine other aspects of Native identities” (“Behind” 27). What Tatonetti describes as Callahan's struggle to imagine Indigenous identities beyond the savage-civilized dichotomy of nineteenth-century discourse in the United States speaks to a much broader, systematic erasure of Indigenous imaginations and identities arising from what Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee) identifies as the silencing of female Indigenous stories: “No wonder our written history speaks so often of war but rarely records descriptions of our songs, dances, and simple joys of living. The voices of our grandmothers are silenced by most of the written history of our people. How I long to hear their voices!” (Mankiller and Wallis 18). As Mankiller suggests, the stories of Indigenous women—past and present—rewrite the oft-repeated narrative of Indigenous death into a vast history of Indigenous life: interconnected stories that offer, as Kim Anderson (Métis) describes, “‘medicines’ of our past” that attest to the “fortitude of our grandmothers” (Life Stages 4). Such stories offer alternative Indigenous identities that Callahan and so many others could only begin to articulate; they provide records of Indigenous women whose resilience has been overshadowed by an androcentric narrative of Indigeneity and Indigenous-US history on Turtle Island.Footnote 4

The Omaha journalist Susette Bright Eyes La Flesche, the only other Indigenous woman known to have published contemporaneously about Wounded Knee for a national audience, offers another set of sidelined stories that Mankiller longed to hear: the nonfictional stories of matrilineal kinship that sustained a surviving community through a moment of massacre. Like Callahan and other nineteenth-century Native American women writers, Bright Eyes works within a similar rhetorical mode of sentimentalism because of how she directly addresses settler readers and narrativizes the Indigenous domestic. Her work, however, clearly prioritizes the relationality of Indigenous women as an enduring example of communal solidarity. Paula Gunn Allen (Laguna Pueblo) recognizes such female-centered stories as representing gynocritic lifestyles and systems of self-governance that inform intergenerational acts of Indigenous nationhood (2). To read Bright Eyes's journalistic prioritization of Indigenous domesticity only within the framework of US-Christian domesticity, especially at a time when federal Indian boarding schools were forcing Indigenous girls to submit to Christian-patriarchal domestic roles, negates the strategies through which Bright Eyes reclaims Indigenous domesticity as an integral space of matrilineal self-governance.Footnote 5

Bright Eyes's focus on the long-overlooked stories of Indigenous women rewrites Indigenous histories in ways that provide precedents for current practices of Indigenous feminism. As Mishuana R. Goeman (Tonawanda Seneca) and Jennifer Nez Denetdale (Diné) suggest, part of the practice of Indigenous feminism is to “open up spaces where generations of colonialism have silenced Native peoples about the status of their women and about the intersections of power and domination that have also shaped Native nations and gender relations” (10). By developing relationships with and prioritizing the experiences of Lakota women at Wounded Knee as a counter to the memorialized history of androcentric power, Bright Eyes's writings offer an early body of stories that reinstate Indigenous women as the surviving center of Indigenous nations and gender relations. In fact, Bright Eyes's attention to the status of living Indigenous women in a moment of horrific settler colonial violence follows a journalistic ethic that foregrounds what Hokulani K. Aikau (Kanaka ‘Ōiwi), Maile Arvin (Kanaka ‘Ōiwi), Goeman, and Scott Morgensen identify as the core principles of current Indigenous feminism: localizing the struggle, bringing people together, and engaging the community (85–87). Remembering the rhetorical and embodied method, impulse, and ethic of Bright Eyes's reporting at Wounded Knee reframes this infamous moment of settler colonial violence as a story of Indigenous survival—a story of Indigenous women ensuring an otherwise impossible future for Indigenous nations.

Remembering Bright Eyes at Wounded Knee

Fundamental to Bright Eyes's work at Wounded Knee was her long-standing public insistence on cultural, spiritual, and legal Indigenous personhood. As an inductee to the US National Women's Hall of Fame and the oldest child of Principal Chief Joseph “Iron Eyes,” Bright Eyes has been remembered as “the Emancipator of a Race” for her advocacy on behalf of the Omaha, particularly throughout and after the 1879 trial Standing Bear v. Crook (Miller 394), in which a federal judge “declared for the first time in the nation's history that an Indian was a person within the meaning of U.S. law” (Starita 10).Footnote 6 While the trial set legal precedent for the civil rights of Indigenous peoples in the United States, the ongoing national attention to the violence of Wounded Knee has, as Richard Morris and Mary E. Stuckey argue, cultured the US public to remember Indigenous death in order to conveniently forget the ongoing realities of Indigenous life (1). Bright Eyes's long-overlooked eyewitness accounts of Indigenous women's resilience at Wounded Knee counter settler colonial narratives and founding myths about the United States and about the suggested demise of US Indigeneity. Her history offers strategies to sustain the ongoing cultural, spiritual, and political resurgence of Indigenous peoples in the present and into the future.

Bright Eyes and her white husband, Thomas H. Tibbles, traveled to Pine Ridge, South Dakota, where both penned articles for the Omaha World-Herald. Bright Eyes was already a widely respected journalist and lecturer on Indian affairs in the United States, and she was commissioned by the newspaper to report on Wounded Knee, yet scholars have consistently reduced her role at Wounded Knee to “the wife of Thomas Tibbles” (Jensen et al. 131). This oversight is but one example in a long history of what Goeman and Nez Denetdale describe as the “violence perpetuated through erasures” of Indigenous voices in historical narratives (13; see 12–13). As Bright Eyes's reporting shows, Bright Eyes was a fearless friend to the Lakota, a fact finder, nurse, witness, and persistent journalist who offered a perspective that nobody else could.

Bright Eyes was welcomed as part of the Pine Ridge community, unlike the many war correspondents who wrote for “city editors slavering for bloody headlines” (Wilson 333). She brought along her Yankton Dakota brother-in-law Charles Picotte as a translator, stayed with a Lakota host rather than at the agency hotel, and focused her stories on the daily realities of the local community (333). Bright Eyes sought out and accepted her relational responsibilities as an Indigenous relative and guest, and she chose to participate in the form of kinship that Daniel Heath Justice (Cherokee) describes as an essential Indigenous cultural understanding that has survived repeated colonial attempts of eradication: “an active network of connections, a process of continual acknowledgement and enactment” (Why 41–42). Through such relational proximity, Bright Eyes focuses readers’ attention on how the relationships of Lakota women are central to the legitimacy of Indigenous religious practice, personhood, and the continuance of Indigenous nationhood.

On the day of the massacre, 29 December 1890, Bright Eyes remained in the agency chapel turned hospital to attend to her wounded relatives while other correspondents rushed to publish their shortsighted stories of Indigenous death. She stayed alongside the non-Indigenous poet and Indian supervisor Elaine Goodale and the Santee Dakota physician Charles Alexander Eastman (Ohíyesa) to fulfill her kinship obligations and carry out what Justice describes as the challenging work of sustaining Indigenous “life and living” (“‘Go Away Water!’” 150). By prioritizing the people over the popular demand for frontier news, Bright Eyes ensured an avenue through which wounded women could express their stories of suffering and survival. She disregarded military dictates and enabled a church full of wounded Indigenous women and children to express their fear and pain, as well as their strength and survival—stories even sympathetic non-Indigenous reporters, such as Tibbles, struggled to understand or express (Tibbles, Buckskin 324).

From her unique position, Bright Eyes offers what seems to be the first published Indigenous woman's eyewitness account of Wounded Knee. In his comprehensive history of nineteenth-century frontier newspapers in the United States, Hugh J. Reilly recognizes Bright Eyes as “one of the first female war correspondents to be officially employed by any American newspaper and . . . certainly America's first female Native American war correspondent” (117). Reilly describes her account as the exception to the national press's deference to the feelings, attitudes, and thoughts of the military throughout the so-called Indian Wars (130). Yet he cites her coverage only briefly in his half-century chronicle without commenting on the intergenerational legacy of her stories sharing the experiences of Indigenous women at Wounded Knee.Footnote 7 In fact, the only passage by Bright Eyes that Reilly directly features in his coverage of Wounded Knee is her single, postmassacre depiction of victims, as if she too wrote largely of violence and death (111). Beyond mapping Bright Eyes onto the national narrative for her contextual significance as the first Indigenous woman writer of Wounded Knee, this essay analyzes how Bright Eyes's reporting evinces methodological, rhetorical, and textual patterns of Indigenous kinship that center Indigenous women in the narratives of intergenerational Indigenous resilience.

Resisting a National Narrative of Violence

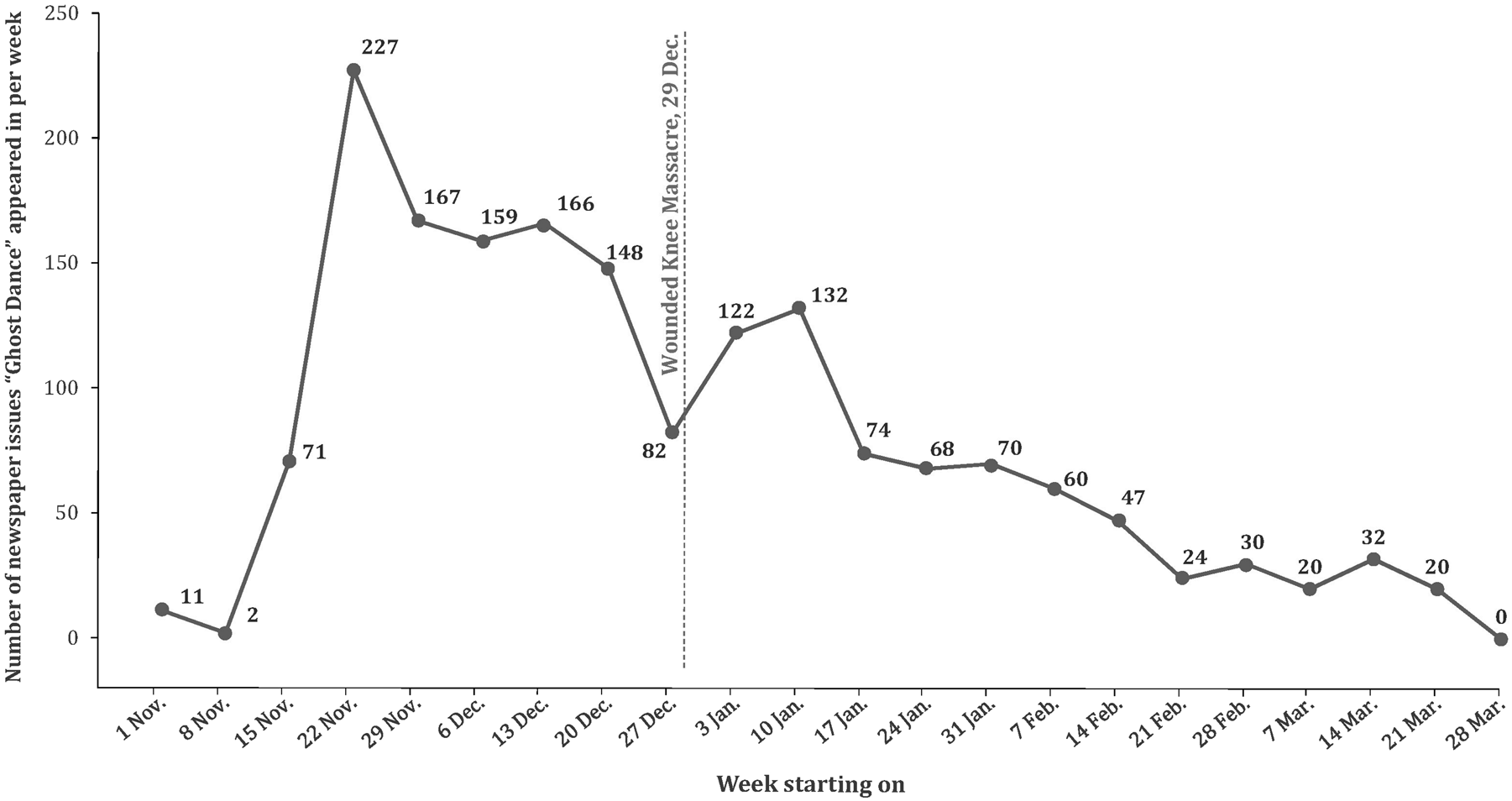

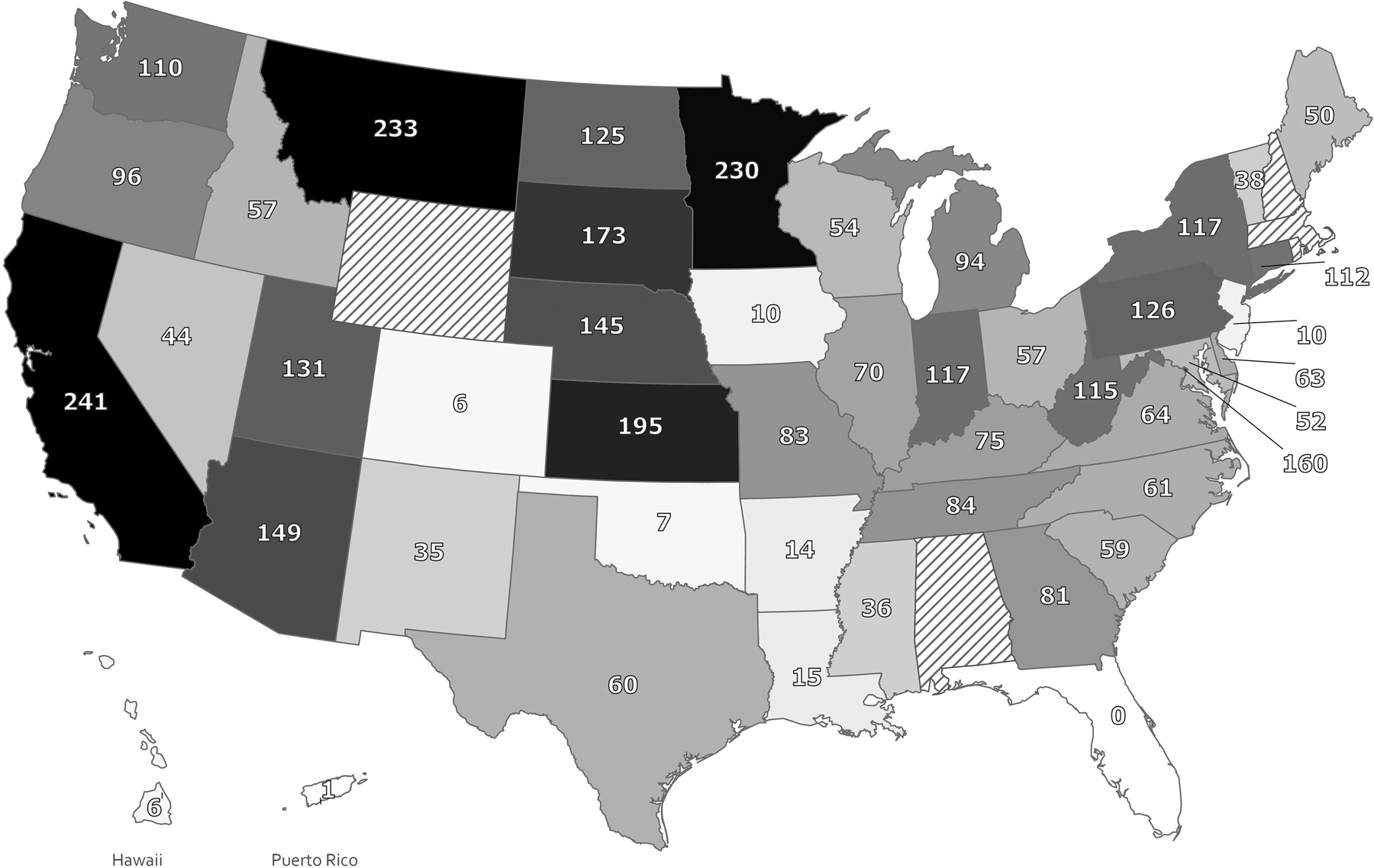

In the months leading up to Wounded Knee, the Ghost Dance, or “Messiah Scare,” had become national news, and at least 250 newspapers offered diverse perspectives on what most journalists described as another impending Indian war (see fig. 1).Footnote 8 These reports ranged from sympathetic articles about the “Indians” and the “Sioux” to racist rants about “redskins,” “bucks,” and “squaws.” Sympathetic or not, out of the more than seventeen hundred national newspaper issues that covered the Ghost Dance from 1 November 1890 to 31 March 1891, only two articles referred to Ghost Dance practitioners as “human.”Footnote 9 The first article states, “If consolidated by a common purpose, the savages should rise and propelled by that strongest of all human motives, religious fanaticism, make war upon the whites” (“Indian War Possible”; our emphasis). The second is similar: “We do not blame Indians for not liking white men, for they come in contact with specimens of the race that are as much below them in the human scale as they are below the highest products of white civilization” (“Some Thoughts”; our emphasis). Such sub- and almost-human rhetoric carried the conversation around the Ghost Dance and the subsequent story of Wounded Knee throughout the United States in newspapers publishing more than three thousand reports in at least forty-six US states and territories (see fig. 2).Footnote 10

Fig. 1. Weekly appearances of “Ghost Dance” from 1 Nov. 1890 to 31 Mar. 1891 in the 371 newspapers in the Chronicling America dataset.

Fig. 2. Map of the United States that illustrates the widespread contemporaneous newspaper coverage of the Ghost Dance. The shading shows the number of newspaper issues that mention “Wounded Knee,” “Pine Ridge,” or “Ghost Dance” between 1 Nov. 1890 and 31 Mar. 1891. The states without numbers had no newspapers in Chronicling America during this time.

Unlike most of the emerging daily newspapers across the United States, especially those published in the so-called frontier states, the Omaha World-Herald remained consistently sympathetic to the Sioux throughout the months leading up to and following Wounded Knee. Established in 1889 by Gilbert H. Hitchcock, during an era that gave rise to a market-driven national news, the World-Herald maintained Hitchcock's self-proclaimed commitment to provide Nebraska with a “newspaper of virtue” with “no alliances of any kind” (qtd. in Reilly xvi).Footnote 11 As a result, while other newspapers sent war correspondents that “were a rare combination of adventurers and journalists . . . ‘more gifted in imaginative writing than in accurate reporting’” (Elmo Scott Watson qtd. in Reilly xvii), the World-Herald began its coverage of Wounded Knee by pointing out the ineptitude of federal Indian policies and practices, which are “but a part of the general impression which this government and the people in it have always cherished, that the Indian has no right to any ideas of his own, or indeed to any nationality of his own” (qtd. in Reilly 113–14). Writers for the World-Herald blamed the federal government, Indian agents,Footnote 12 local settlers, and other newspapers of exaggerating conflict solely for economic gain and sought to persuade readers to avoid, rather than provoke, war (Reilly 115–16). Instead of seeking profit regardless of the human cost, the World-Herald pursued a fact-based discourse through a form of “active witnessing” led by Bright Eyes. By commissioning Bright Eyes, the newspaper demonstrated editorial practices that have since become fundamental to what media scholars describe as “radical journalism,” a form of journalism that establishes a “counter-discourse to those found in mainstream media” by employing techniques such as “native reporting, where first-person, activist accounts of events are preferred over detached commentaries” (Atton 491). Although Bright Eyes, as the World-Herald's only “native reporter” at Wounded Knee, was clearly writing for a settler audience, she reported as an Indigenous relative with local collaboration and support to analyze the historical and sociopolitical situation. She wrote to transform her readers’ consciousness into a collective will to change the local and national “Indian” issue.Footnote 13

As a relative, Bright Eyes insists on Ghost Dancers’ humanity, emphasizing their traditional spirituality as a possible humanistic common ground between Indigenous people and her largely white-Christian audience, instead of subjugating Ghost Dancers to the widely perpetuated status of not quite human (that is, not quite white). She began her Wounded Knee reporting on 7 December 1890 with an article titled by the newspaper editors as “What Bright Eyes Thinks.” Offering her perspective on the Ghost Dance, her article begins, “The causes that brought about the ‘Messiah scare’ may seem to be very simple if one only stops to think that, first of all, the Sioux are human beings with the same feelings, desires, resentments and aspirations as all other human beings.” Bright Eyes frames her article as a plea for empathy grounded in the shared experience of being human and seeking a savior. Aware of the story of savagery that had been circulating in the national news weeks before any actual tension at Pine Ridge, Bright Eyes resists a reactive retort; instead, she focuses on the shared human desire for spiritual and temporal salvation.

As the article continues, Bright Eyes blames the federal government for its broken promises of self-appointed temporal guardianship and concludes by returning to her fundamental message of shared humanity: “The Indian is more amenable to a government of law than he is to one maintained by arbitrary authority, as are all ‘human beings.’” By insisting on the humanity of the Sioux in the press, Bright Eyes reclaims Indigenous personhood, the very personhood that had been legally affirmed only eleven years before. Bright Eyes's initial article begins along the path of what Anderson describes, in her field-shaping reconstruction of Native womanhood, as “the identity formation process”; Bright Eyes “resist[s] negative definitions of being, reclaim[s] Aboriginal tradition, and construct[s] a positive identity by translating tradition into the contemporary context” (Recognition 15). Beyond reconstructing a positive Indigenous identity that was grounded in the legal recognition of Indigenous personhood and a legitimization of Lakota religious practice, Bright Eyes understood that “the status of ‘human,’” as Justice argues, “is intimately embedded in kinship relations” (Why 41). In other words, through her reclamation of the Lakota as “human beings,” Bright Eyes begins her reporting at Wounded Knee by stating her obligations as an Indigenous journalist.

On 11 December 1890, the World-Herald announced that Bright Eyes and her husband would “go to the bottom of the Indian troubles and tell the readers . . . the truth. . . . They will visit the Sioux. No other newspaper correspondents have done or could do this” (“‘Bright Eyes’ and Mr. Tibbles”). Although surely not anticipating the significance of sending an Omaha woman journalist to what would become one of the most infamous moments in Indigenous-US history, by acknowledging that “no other newspaper correspondents . . . could do this” the newspaper gestures to the reality that Bright Eyes's visit to the Sioux would be distinct from the visits of other war correspondents who were already flooding into Pine Ridge. Bright Eyes and her husband soon became the front-page featured voices, and the World-Herald congratulated itself “on having two absolutely truthful and conscientious persons to furnish its readers with accurate information on this troublous subject” (“‘Bright Eyes’ Sees”). In total, the World-Herald published at least twenty-five of Bright Eyes's reports depicting the situation and aftermath of Wounded Knee, and reprints appeared in at least fourteen other US states and territories.Footnote 14

While newspapers across the United States fabricated sensationalist accounts of frontier violence to justify what they reported as an unavoidable war,Footnote 15 Bright Eyes responded with an article entitled “Fleeing from Each Other.” Instead of fueling the frenzied national narrative of imminent violence, Bright Eyes assures settler readers that “there is no cause to fear.” She challenges them to see through the fearmongering created by federal agents and the voyeuristic sensationalism of other newspapers, and she offers a revelatory report of the premassacre situation at Pine Ridge:

Here on the one hand are hundreds of white people leaving their homes because they are afraid of the Sioux. On the other hand there are hundreds of Sioux fleeing to the Bad Lands because they fear the white people, troops having been sent among them: No one has been killed, no blood shed, no assault made by the Indians on the whites and none on the Indians by the whites.

Bright Eyes brings the Sioux and local settlers together in a commonality of fear caused by federal agents and economic-driven alarmists. She renders both Sioux and whites as victims, though with a clear distinction of severity, of federal Indian policy and profit-driven popular discourse. Her article goes on to reassure her readers and to encourage them to recognize how they, too, suffer from the fear tactics and federal actions that “always will result as long as the present system is in existence.” Bright Eyes describes how the lives of both the local Sioux and the border-town settlers were being disrupted by the fictional reports circulated by the federal Indian agents and the national newspapers. By calling attention to Indigenous-settler commonality, she extends the relationality with which she began her reporting to her settler readership as a collective call for allies against the federal Indian system, which, as Bright Eyes attests, was built on and has always profited from a policy of violence.

Two days later, the World-Herald emphasized the “notable contrast” between Bright Eyes's reporting and “the frantic and contradictory dispatches of the casual correspondents,” and it offered its own editorial summary of her daily reports: “That is the situation. An Indian . . . has liberty which he may not use; he has a religion which he may not follow; he has amusements which are forbidden; he has customs of his own which are denied him. In short, he has all of the disadvantages and none of the advantages of so called civilization” (“‘Bright Eyes’ Sees”). Bright Eyes's reporting shaped the overall tone of the World-Herald's accounts of Wounded Knee. Her articles for the World-Herald, addressing the sociopolitical context and the unilateral attempts by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to assimilate Indigenous lands and peoples and alienate them from long-standing systems of self-determination, were unique among state and national newspapers. Bright Eyes draws her editors’ and readers’ attention to settler colonial “occupation and erasure” (Simpson 34) as the root causes of the ongoing violence committed against Indigenous peoples, especially Indigenous women and girls (Bourgeois 68). And in her call to abolish the BIA she refuses, as Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg) argues is necessary for present-day Indigenous resurgence, “colonialism and its current settler colonial structural manifestation” (34).

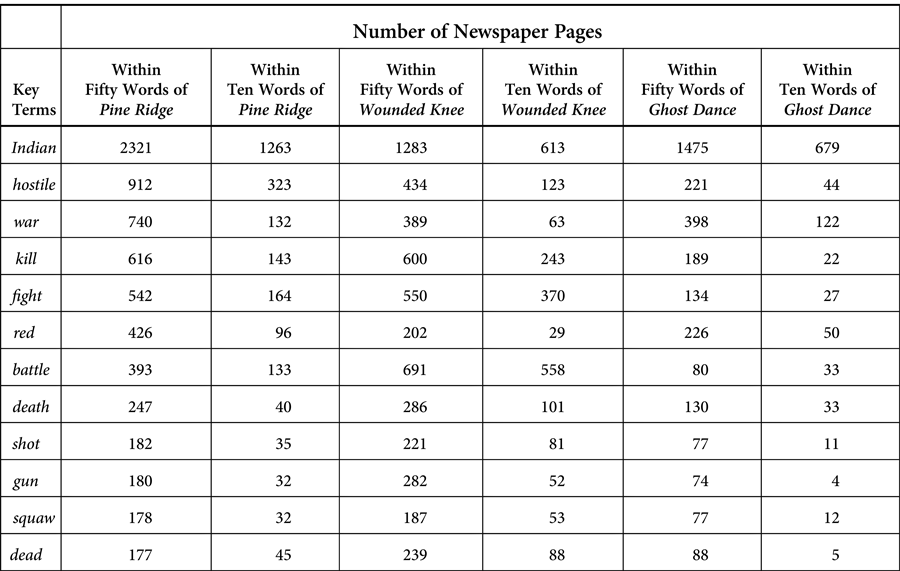

On 14 December 1890, Bright Eyes reiterated her plea to readers not to subscribe to the sensationalist news that continued to spread stories of supposed savagery, stories that would prepare readers to accept whatever means of “civilizing” necessary to regain a sense of sociopolitical stability that had never actually been threatened. Throughout the weeks leading up to the massacre, the three terms most frequently associated with Pine Ridge were Indian, hostile, and war (see table 1). In her article entitled “Nothing Warlike There,” Bright Eyes likens local and national newspapers’ obsession with an impending war to Buffalo Bill's Wild West show:

I apostrophize those Sioux warriors who made such gallant charges on Buffalo Bill's old stage coach with its escort of brave cowboys, all armed to the teeth, riding on fiery chargers by the side of the rocking old coach with its royal occupants; said coach being drawn by four horses going at full speed, of which exciting scene I was a spectator in London, and they think one American stage driver too small game to pursue even in these war-like times.

By directly comparing the news coverage at Pine Ridge to the charade of Buffalo Bill's Wild West, Bright Eyes underscores how her peers played on the popular imagination of cowboy-Indian conflict to sell a shocking story. Through her satirical comparison to Buffalo Bill's internationally applauded form of colonial entertainment, Bright Eyes addresses how, as Anita Hetoevėhotohke'e Lucchesi (Cheyenne) argues regarding the long-standing economies of sensationalizing Indigenous trauma, “these settler-generated images of trauma-saturated Indigenous communities, as well as the resulting representation of Indigenous women and girls as unable to function on their own, create an economic system that thrives from continued trauma and violence” (57). Bright Eyes's direct condemnation of the sensationalizing of violence foresaw how such narratives set the stage and the stakes for a final, climactic frontier showdown. By repeatedly asserting Lakota humanity and directly calling for settler allies in an era when the national news declared—at times demanded—Indigenous death, Bright Eyes documented and affirmed the astounding resilience of Indigenous women's relations.

Table 1. All Newspapers in Chronicling America from 1 November 1890 to 31 March 1891

Reporting on Indigenous Women at Wounded Knee

On 15 December 1890, exactly two weeks before the massacre, the expectant nation awoke to read the first full scene of the violent drama that newspapers had been so impatiently teasing for weeks. In an altercation with agency police, the Hunkpapa Lakota leader and elder Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake) had been killed. Instead of focusing on Sitting Bull's murder, though she surely understood the local and national gravity of the moment, Bright Eyes spoke with a fleeing mother and her three young daughters who had made it safely into Pine Ridge. Bright Eyes tells their story of having fled the Rosebud Agency because of the threat of US troops only to have to flee again after realizing that there were also troops stationed at Pine Ridge (“At the Pine Ridge Agency”). By shifting her readers’ attention away from the death of Sitting Bull to the resilience of a fleeing Lakota mother, Bright Eyes locates Lakota survival and futurity in the bodies and stories of Lakota women and girls. She demonstrates how, as D. Memee Lavell-Harvard (Wikwemikong First Nation) and Anderson explain of present-day Indigenous mothers, “for centuries, strength, independence, and self-reliance have defined [Indigenous] mothers, and interdependent supportive networks of kin have shaped Indigenous motherhood” (6). Bright Eyes's attention to mothering reclaims Indigenous motherhood at a time when the BIA was expanding its federal Indian boarding school program, which, as Indigenous scholars have documented, intentionally removed children from and sought to replace Indigenous mothers (Fontaine et al. 252).

Even after the death of one of the Lakota's most influential leaders, Bright Eyes drew her readers’ attention away from the dying men and toward the stories of surviving women and girls, who attest to the ongoing threat of settler colonial violence and the federally sanctioned starvation that had caused them to flee in the first place (“Why They Are Starving”). Bright Eyes's choice to shift her readers’ attention from frontier violence and intratribal conflict to the realities of a surviving mother demonstrates a journalistic ethic of prioritizing the present and future of her Indigenous relations over the incessant pull of hegemonic narratives. By shifting the narrative focus, Bright Eyes raises her readers’ awareness of the violence happening to Indigenous peoples while simultaneously representing the intergenerational endurance of matrilineal Indigenous families. In this way, Bright Eyes acknowledges the realities of settler colonial violence while maintaining a focus, similar to the present-day work of the Cree-Lakota-Métis spiritual caregiver Pahan Pte San Win, on “woman's sacred responsibility as the life giver to the next generation” (271). Like Pte San Win, Bright Eyes chose to “promote the teaching of Woman Sacred” as a necessary counternarrative to the still-dominant systems of settler colonial violence against Indigenous women (Pte San Win 277). By centering her reports on the stories of Indigenous women, Bright Eyes defies what Allen identifies as “the overall program of degynocratization” and reclaims the image of late-nineteenth-century Lakota women as the surviving core of Lakota nationhood—Indigenous mothers who sustain Indigenous nations by carrying and protecting the knowledge, language, land, stories, and bodies of Indigenous nations (42).

Such stories of Lakota women challenge settler readers to move beyond the stereotypes of cowboy-Indian conflict, to humanize war, and to reconsider settler-Indigenous and Indigenous-Indigenous relations. Amid all the chaotic rumors circulating about the agency, Bright Eyes's 18 December article, “Sunset Scenery,” invites readers to pause and consider the structures of so-called civilization that divided the diverse residents of and around Pine Ridge. Of all of her reports, this article is Bright Eyes's most descriptive, leading the World-Herald to preface the piece as “A Beautiful Composite”:

In the streets formed by these various buildings you see white men in all the various stages of civilization (?) from the shabby, unkempt, roughbearded specimen, up (or down) to the citied looking fellow with the invariable cigar in his mouth. . . . There are soldiers, white and colored, to be seen flitting here and there, everywhere, intent mostly on their various duties. Mingled with them all . . . are Indians in the various stages, from the painted savage, wrapped in his Navajo blanket up or down (?) to the semi-civilized, who compromise by wearing a stove pipe hat in addition to the blanket, and up, certainly, to the full blooded Episcopalian Indian minister who officiates at the church yonder.

By disrupting her literary prose with parenthetical asides, Bright Eyes refutes a colonial discourse by repeatedly questioning the so-called civilization that demarcated the settler-Indigenous composite gathered at Pine Ridge. The figurative language of this article also points to another important rhetorical strategy whereby she subverted the genre of sentimentalism and its colonial counterpart, literary journalism, or what David Spurr calls the “rhetoric of empire.” Spurr describes literary journalism as combining “an immediate historical interest with the complex layering of figurative language that conventionally belongs to imaginative literature,” in which the writer “implicitly claims a ‘subjective and independent status’” (9).

Unlike other literary journalists, though, Bright Eyes claims narrative authority not because she remains independent from the immediate situation, thereby categorizing the imperial other, but rather because she proactively becomes interdependent with the immediate community that her writing represents. As a result, “Sunset Scenery” directly confronts—rather than repeats—the colonial categories of empire. While she employs popular terminology such as painted savage—this is the only time she uses the term savage in her articles—she refuses to place community members at definitive points on a social hierarchy. Instead, Bright Eyes invites her readers to question the categorization of human beings, to dismantle the narratives that simultaneously justified and stoked the impending slaughter.

As “Sunset Scenery” continues, Bright Eyes turns her attention to her journalist counterparts and their inability to adequately capture the complexity on the ground. She describes a group of Lakota sharing stories with one another in their language as reporters stand by, unable to understand: “One can give all one's heartiest sympathies to the two reporters who stand ready, alert and with ears cocked, but who alas, might as well have been without those organs of hearing, for nothing can they make out of this strange speech.” Bright Eyes criticizes mainstream reporters, even those who may have sought to engage Indigenous perspectives, who were unable to adequately capture the cultural complexity of Pine Ridge because they lacked linguistic and cultural knowledge. The article goes on to invite readers to reflect on their own limited understandings, internalized prejudices, and the resulting injustices that such attitudes would ultimately enact:

I began to wonder what has brought all these things together here in this one spot. Ministers representing three different denominations, their churches, the government schools, the agent—all this paraphernalia of war, all apparently directed toward the one object of civilizing, taming and subduing a number of human beings, helpless, ignorant, and with hearts burning with a sense of injustice at being misunderstood by their more favored fellow men, who have brought all this machinery to bear on them for the purpose of quelling them, and all of which is ineffectual, because they are hungry and have not been treated with justice. I think the merciful father of us all must be looking in pity on the whole scene.

Here again, Bright Eyes outlines the ever-increasing effects of settler colonialism and questions its ethics, concluding as she began by emphasizing the shared humanity of the Pine Ridge community and placing responsibility for the underlying tension at the door of the BIA, with its long history of genocide in the name of generosity. Bright Eyes subverts the colonial rhetoric of literary journalism to directly incriminate the whole federal Indian system, and her attention to the details of the natural and manufactured spaces of Pine Ridge offers readers a more purposeful collaboration with Indigenous communities that is grounded in the “exposure to the place-based reality of Indigenous people” (Thomson et al. 141). Beyond promoting settler-Indigenous collaboration, however, Bright Eyes offers an early example of journalism grounded in Indigenous-Indigenous collaboration, in which place becomes simultaneously personal and political, in which self-determining nations continue to assert Indigenous authority to sustain relations and govern their own territories.

Bright Eyes sent a second article on 18 December with a title that finally seemed to reflect the rhetoric of her fellow correspondents: “Drama among the Sioux.” As tension was beginning to rise, more refugees from the Rosebud reservation were arriving at Pine Ridge and negotiators were sent out to persuade others to return peacefully to the Indian Agency at Pine Ridge. The drama Bright Eyes depicted—unlike the imagined war of the news reporters she so frequently criticized—was not a violent battle, but rather a public performance of the “Omaha Dance” on the principal street of the agency. The Omaha Dance, as Mark G. Thiel describes it, is “the most popular social and nationalistic . . . demonstration of tribal identity” among the Oglala Sioux (5). Bright Eyes emphasizes the diversity of the ceremonial audience members. She writes that as she neared the open-air arena, “a painted Sioux woman, a stranger to me, gave me a place in front of her, standing behind me with her hands on my shoulders” (“Drama”). Bright Eyes goes on to describe the singing, drumming, dancing, and the gifting of horses, as well as the beautifully detailed regalia, reenactments of heroic deeds, and orations. Bright Eyes reports on the hospitality of her Pine Ridge hosts and the shared joy of witnessing and participating in their ceremonial celebration of Lakota nationhood, instead of basking in the literary suspense of the impending massacre. In her depiction of a Lakota woman welcoming her as a guest, Bright Eyes presents an image similar to what Cheryl Suzack (Batchewana First Nations) describes as a map of Indigenous feminism: a “vision of community relations . . . organized through the values of mutual respect and cultural obligation” (187). Bright Eyes disrupts her audience's expectations of the “drama” at Pine Ridge by depicting living Indigenous women's reciprocity—the practices of kinship that ensure “the continuity of Indigenous nations into the future” (Justice, “‘Go Away Water!’” 150).

On New Year's Eve 1890, the article “Another Indian Battle” appeared on the front page of The New York Times and reported a significant underestimation: “thirty-three of the hostiles bite the dust.” Even journalists writing for the comparatively critical World-Herald, including Tibbles, could not resist the sensational news story of the Wounded Knee Massacre. While the World-Herald and other sympathetic newspapers shifted the Times's narrative from hostile “Indians” to a premeditated “war of extermination,” its articles still bleed with gory descriptions of settler colonial carnage and impending Lakota revenge, carrying such titles as “All Murdered in a Mass,” “Thirsting for Blood Now,” “Braves Shot Down,” and Tibbles's “Red Blood Flows.” In her response to the massacre, Bright Eyes—as the only reporter writing from the military front lines, from the tribal councils and ceremonies (Bright Eyes, “Indian Council”), and from among local Lakota women—resists both the economic- and anger-driven urge to write only of blood, violence, and revenge. Instead, she draws her readers’ attention away from the massacre site by describing the survivors (mostly women and children), detailing their wounds, and sharing their stories—even those originally told to her in Lakota.

The next day, Bright Eyes sent a special correspondence entitled “Horrors of War” that was published on the front page of the World-Herald's 2 January 1891 issue. For the first time in her month of reporting from Pine Ridge, Bright Eyes offers her perspective on the violence. Reporting on what she witnessed as she volunteered in the makeshift agency hospital, Bright Eyes concludes:

I have been thus particular in giving horrible details in the hope of rousing such an indignation that another causeless war shall never again be allowed by the people of the United States. Soldiers and Indians have lost their lives through the fault of somebody who goes scot free from all the consequences or blame. The conviction is slowly forcing itself into my mind that this war has been deliberately brought about. . . . When you see the hardships the soldiers are going through, standing guard through wind and storm, day and night, and look around on the dead and wounded, and think that all this was brought about through the hope of money and land gained from the Indians, the verse of scripture involuntarily comes into one's mind: “What shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his own soul.”

As in her reports leading up to the actual massacre, Bright Eyes humanizes individuals from both sides of the story, casting blame instead on the long-standing systematic attempts to assimilate—or exterminate—Indigenous peoples and to claim their title to Indigenous lands and resources by whatever means necessary. Many national newspapers sought to justify those means through a shared racist rationale of presumed white-Christian superiority and the inevitable process of so-called civilization. In direct contrast, Bright Eyes never uses such stereotypical terms as redskin, scalp, or squaw. She refuses to portray Indigenous peoples as dispensable and she never repeats the colonial narrative of Indigenous women as, according to the Cree-Métis scholar Emma D. LaRocque, “vulnerable to physical, verbal, and sexual abuse” (74). Rather, Bright Eyes reverses the dehumanizing depictions of Indigenous death by reclaiming the traditions of Indigenous life and reports on Lakota women's resilient acts of Indigenous being.

Remembering Resilience

By largely ignoring Bright Eyes's eyewitness reports, the story of Wounded Knee presented by late-nineteenth-century newspapers has remained mostly unchanged despite more than a century of ongoing research and reinterpretation. Dee Brown's 1970 national bestseller, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, remains perhaps the most widely read history of Wounded Knee. Presented as the closing chapter of Indigenous-US relations, Brown's popular history had the stated goal that “perhaps those who read it will have a clearer understanding of what the American Indian is, by knowing what he was” (xix). In the decades since Brown's dramatic retelling of the American frontier, historians have gathered and reinterpreted additional newspaper accounts, military reports, and testimonies (Jones; Carroll). Indigenous historians and authors have worked to reclaim the institutional and popular narrative through a combination of children's books, community-based collections of stories, and academic histories (Wood; Josephy et al.; Gonzalez and Cook-Lynn). Researchers have returned to a range of previously overlooked or underanalyzed primary sources, including original records from military personnel, tribal leaders, and other eyewitnesses (Foley; DiSilvestro; Greene, American Carnage and Soldiering; Grua). Others have worked to recontextualize Wounded Knee as part of the longer history of US-settler colonialism (Viola; Ostler; Richardson; Hillstrom and Hillstrom; Fishkin). Each decade of retelling Wounded Knee has brought with it new sources that offer important angles for understanding the massacre and its historical and ongoing consequences. Still, despite the ever-broadening body of records and reports, the dominant narrative of Wounded Knee can still be summed up in the title of the Lakota-Dakota historian Frank B. Zahn's 1967 book, The Crimson Carnage of Wounded Knee: An Astounding Story of Human Slaughter.

Whereas academic histories, national narratives, popular culture, and contemporary political pundits continue to retell Wounded Knee and other such moments of Indigenous-US relations by depicting either the spectacle or the devastating reality of Indigenous death, Bright Eyes offers an alternative account. She reports on Indigenous humanity rather than hostility. She shares the otherwise silenced stories of Indigenous women and girls instead of interviewing generals and chiefs. Even when recounting moments of horrific violence, she draws readers’ attention to a surviving grandmother “sitting on the floor with a wounded baby on her lap and four or five children around her, all her grandchildren” (“Horrors of War”). By replacing lists and numbers of casualties with stories of surviving women, whom the Swampy Cree storyteller Louise Bird describes as the traditional “medicine people,” sustaining one another, Bright Eyes chooses to witness Indigenous cooperative resilience against the root of the so-called Indian problem (qtd. in Anderson, Life Stages 147). Like Makere Stewart-Harawira (Waitaha) and so many other present-day Indigenous women who practice Indigenous feminism to resist settler colonialism and imperialism, Bright Eyes bears witness against settler colonial violence through the resilient voices of mothers and grandmothers, “call[ing] for a new model for being in the world . . . a political ontology of compassion, love and spirit” (Stewart-Harawira 127). Throughout her articles, Bright Eyes demonstrates a core characteristic of Indigenous kinship, what Justice calls a deep “capacity for empathy” (Why 77). Her Wounded Knee journalism exemplifies the “generosity, humility, and kindness” that Simpson insists are required to secure a better Indigenous present and ensure better Indigenous futures (246).

In her final reports from Pine Ridge, Bright Eyes recognizes settlers who sought relationships of respect and reciprocity with their Indigenous neighbors and continues to contextualize Indigenous anger at the immediate human costs of federally funded Indigenous extermination. Despite her generous desire to capture both sides of the story and thereby expand relations by inviting her non-Indigenous readers to share in the obligations of kinship, she confesses, “I don't know that I can say both sides, either, as there are scarcely any of the Big Foot band left to tell the tale except the wounded and dying” (“Negotiating for Peace”). Bright Eyes's final call for compassion and her admission of the impossibility of telling the full story of Wounded Knee challenge today's readers and writers of Indigenous-US relations to adopt her journalistic ethic of grappling with the daunting responsibility to search out unavoidably incomplete stories in ways that promote peace, honor the universal humanity of their historical subjects and their surviving descendent communities, condemn racist systems, and emphasize stories of survival over reports—even if offered in the form of sympathetic critiques—of supposed settler colonial success.

As an afterword to the 2014 Oxford Handbook of Indigenous American Literature, ku‘ualoha ho‘omanawanui (Kanaka ‘Ōiwi) offers an oft-quoted Hawaiian proverb to encourage students and scholars to carefully consider the stories they choose to recover, recontextualize, retell, and write: “I ka ‘ōlelo ke ola, i ka ‘ōlelo ka make, ‘in words is the power of life, in words is the power of death’” (675). The simultaneous invitation and warning from ho‘omanawanui challenges readers to follow Bright Eyes in replacing the long-perpetuated stories of Indigenous death with stories of Indigenous survivance. At a time when federal Indian policy removed Indigenous children from their mothers, when Indigenous peoples were just beginning to be recognized as persons under US law but popular discourse was still demanding that they were less than human, when national media was proactively premeditating Indigenous death, when the federal government was still awarding medals of honor to celebrate Indigenous massacres, Bright Eyes reported on the resilient relations that have always supported Indigenous life. Remembering Bright Eyes's Wounded Knee reporting now—when states and extractive industries continue to fight to delegitimize Indigenous nations, when Indigenous women and girls continue to go missing and to be murdered without prosecution, when politicians and popular media continue to rely on racist tropes to characterize Indigenous peoples—challenges readers to recover, remember, and retell an alternative set of stories that, as Mankiller suggests, have been there all along. As Bright Eyes reports, such stories have endured in the bodies and relations of Indigenous women—the traditional medicine people—who have always been at the center of Indigenous knowing and being.

Writing both as an eyewitness and as the sole Indigenous female reporter at Wounded Knee, Bright Eyes prioritizes the stories, songs, dances, and ceremonies of Indigenous women and girls—the grandmothers Mankiller longed to hear—that are necessary to rewrite the national narrative of Indigenous-US relations as centuries of Indigenous being, despite every attempt to ensure Indigenous death. By reporting on the resilient relationships of Indigenous women at Wounded Knee, Bright Eyes confronts the settler colonial narrative that is perpetuated, as Michelle Good (Red Pheasant Cree) argues, by the “triumvirate of media as curriculum, government policy, and ongoing oral history” with stories of resilience, kinship, and a regynocraticization of Indigenous communities and stories (99). Amid the reality of the settler colonial massacre at Wounded Knee, Bright Eyes shared stories of Indigenous survival and of Indigenous women capable of sustaining Indigenous nations and relations then, now, and for many generations to come.