The United States emerged in the 1780s after a successful war of independence against Britain, and when it fought wars in the nineteenth century, it primarily chose conflicts that were meaningful for national development. A war against neighboring Mexico in the 1840s vastly expanded the United States’ territory. War and genocide against Native Americans opened up additional space for American expansion. Civil war in the 1860s prevented a division of the country. The United States’ nineteenth-century wars laid the foundation for a massive increase in the capacity and legitimacy of its central government (Bensel Reference Bensel1990) and motivated substantial investment in transportation, communications, and industrial infrastructure. The ensuing expansion of its wealth and power in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries established the United States as a great power, and its victorious interventions in the twentieth century’s world wars cemented its status as the international system’s dominant state (Organski Reference Organski1958, chapter 12).

This abbreviated version of U.S. history is a list of events. The sequencing of these events and the interconnections between them describe the process by which the United States emerged as a small and weak political entity and then evolved into a global power. The events were part of its state-making process. The United States may be atypical in the success of its state making, but it is typical in that events like these are the constituent parts of the state-making processes of all states. Other countries have also attempted to defend their territories and develop their populations through wars and the expansion of administration, thus promoting legitimacy and capacity. Some have succeeded like the United States, whereas others have failed.

State-making (SM) scholars focus on the process by which states come into existence, prosper or stagnate, expand or contract, persist or decline. The main strength of this approach is the rich context it provides about the connections between events. A weakness is that cumulative knowledge is difficult to achieve. For example, SM researchers disagree about whether war is merely one or the most important event within the state-making experiences of states. They also disagree about the extent to which different regions or different historical eras feature different types of events as the most prominent influences on state making.

International relations (IR) researchers focus on wars, interventions, genocide and mass killing, territorial changes, economic development, and the foreign economic and diplomatic policies of the states that comprise the international system. Most IR scholars restrict their analyses to only one of these types of events at a time. All sorts of consensus judgments about the causes, characteristics, and consequences of events have been reached, but little or no sense of the process linking events is evident in IR scholarship. Also missing is any sense of connections across topics within IR research.

In this article I argue that the rich contextualization of SM research can offer new ways to envision a good deal of IR research and provide a framework that summarizes the lessons that IR researchers may learn from SM research. This framework emphasizes thinking about state behavior as being motivated by the desire to survive. State existence starts with state birth and ends with state death, and the length of time between these two points varies from state to state but is influenced by each one’s capacity and legitimacy. The process orientation of SM research reminds IR scholars to remember that how high a state’s odds of survival are at any given moment is influenced by events in its past. If those events have decreased the state’s capacity and diminished its legitimacy, the state is closer to death than if those past events have increased capacity and enhanced legitimacy. At the same time, states that are closer to death are less likely to enjoy successful outcomes in the wars they fight, the diplomatic campaigns they undertake, or their efforts to revitalize their economic fortunes. In this way, each state’s history of past events influences both the likelihood and likely outcome of subsequent events. This is an uncommon way to conceptualize events of interest to IR researchers. Also novel is the recognition that, if enhancing capacity and legitimacy so as to prolong the state’s existence is the motivation of states when selecting military, diplomatic, and developmental policies, then those policies are best conceived of as substitutes or complements to each other and should not be studied in isolation. Based on these insights, the framework suggests new research foci for IR researchers. Focusing on process and on different behaviors as substitutes or complements suggests corresponding research design implications. Whether IR researchers take the framework seriously, they would be wise to consider some significant threats to inference it suggests, which may possibly corrupt existing IR research.

Before presenting the framework, I want to be clear about the limits of my theoretical intentions and epistemological scope. The framework does not offer specific testable hypotheses based on clearly identified causal mechanisms. Instead, it directs attention to connections across a wide range of topics and invites more specific theorizing with respect to each. I offer the framework at this abstract level because I believe the connections it draws between SM and IR research are fascinating and worth exploring in more detail. This article is an invitation to IR scholars to develop more detailed theories based on the framework. As I make clear, my epistemological orientation is squarely within the positivist tradition. Large literatures in both SM and IR provide an interpretivist approach to many of the topics touched on in this article. Although there are insights to be gained from these literatures, I do not engage them here because of space constraints.

Before presenting the framework, it is essential to clarify its key concepts: the state, state birth, state death, capacity, and legitimacy. All are contested concepts, and some may reject the conceptual definitions I use. I hope that being clear about my conceptual definitions will make it easier for readers to think through my framework and to offer improvements based on alternate definitions of the central concepts. After providing those definitions, I then turn to the framework itself. Next, I draw out two main implications of the framework: first, that IR researchers should build into their theories the recognition that past events and outcomes influence present events and outcomes, and second, that many of the actions that states take in the international system are elements of their survival strategies and as such are complements and substitutes. Along the way I offer methodological suggestions for dealing with the framework’s implications.

Conceptual Definitions

To understand my framework, which is about how states struggle to survive, it is essential to be clear about what I mean by the state; survival is the time between state birth and state death, so those two terms also need careful definition. Finally, states survive by doing what they can to augment or at least maintain their capacity and legitimacy, so those two terms also require conceptual definition. Where possible, I discuss measures of these important concepts as well.

The State

The state-making literature has no shortage of definitions of the state. I favor Centeno’s:

The state is defined as the permanent institutional core of political authority on which regimes rest and depend. It is permanent in that its general contours and capacities remain constant despite changes in governments. It is institutionalized in that a degree of autonomy from any social sector is assumed. Its authority is widely accepted within society over and above debates regarding specific policies. While the nature of its agency may be problematic, it does possess enough coherence to be considered an actor within the development of a society. That is, even if we may not speak of the state “wanting” or “thinking,” we can identify actions and functions associated with it. On the most basic level, the functions of a state include the provision and administration of public goods and the control of both internal and external violence. (Centeno Reference Centeno2002, 2)

The state is thus an actor that is distinct from the territory within which it acts and the population over which it asserts predominance. Territory is best seen as representing a set of resources on which the state hopes to draw.

Space does not permit a lengthy discussion of the comparability of state-like entities such as unrecognized states (Caspersen Reference Caspersen2012), de facto states (Florea Reference Florea2014), or territorial rebels who behave like states (Arjona Reference Arjona2014; Huang Reference Huang2016b; Staniland Reference Staniland2012). Such nonstate entities possess most of the features central to Centeno’s definition. The clearest difference between them and sovereign states is that they lack recognition. As a result they generally have lower capacity and are less legitimate “states,” with consequently worse survival prospects. In the discussion that follows I refer to sovereign states, but the framework developed here applies to all territorial states and state-like entities struggling to survive.

State Birth

It is difficult to think of a state without a territory and population to govern. This inherent territoriality provides the definition of when a state is born: It is born when the institutional core of political authority first gains control of populated territory. This might occur by decolonization or secession, via the dissolution of an empire, by diplomatic agreement, or through the independent efforts of local power brokers constructing a state indigenously. Also consistent with Centeno’s definition of the state, it is possible for a new state to emerge in the territory and assert control over the population of an older state through revolution or comparable comprehensive change of the fundamental institutions that previously provided public goods and maintained order. For example, a Cuban state was born via decolonization in the early twentieth century, but a second Cuban state was born in the late 1950s by revolution.

State Death

The same inherent territoriality informs the definition of state death: a state dies when the institutional core of political authority no longer controls any territory or people. Fazal defines state death as occurring “when one state takes over another, or when a state breaks up into multiple, new states” (2007, 1) Death can be by conquest, colonization, prolonged military occupation, dissolution, and voluntary union.Footnote 1 Although Fazal’s definition of state death is not explicitly about territorial control, every instance of state death in her data set involves a different territory’s “institutional core” asserting control over the now-dead state’s territory. Generalizing beyond Fazal’s definition of state death, I envision revolutionary upheavals that replace the “permanent institutional core” of a state as an additional form of state death.

State Capacity

By state capacity I mean the ability of the state to govern its territory and population, as well as to extract resources from its people and territory with which to achieve that governance. The state’s task is difficult. Governance often generates resistance, and tax extraction always does. Thus, more capable states are better able to create effective institutions, organize economic and political life within their territories, and generate the revenue to pay for these activities while keeping resistance to a minimum. Capacity is notoriously difficult to measure, although many scholars favor some measure of tax collection (Arbetman and Kugler Reference Arbetman and Kugler1997; Hendrix Reference Hendrix2010). The ratio of taxes to GDP is a standard measure of capacity in quantitative state-making research (Thies Reference Thies2004). Other scholars offer a more expansive conceptualization of capacity, focusing on human development outputs in addition to economic variables (Carment, Prest, and Samy Reference Carment, Prest and Samy2010, chapter 3).

State Legitimacy

Legitimacy is an important complement of capacity. When a state enjoys legitimacy, the population residing within the state’s territory accepts the state as appropriate, perhaps even natural. Scholars largely agree about conceptual definitions of legitimacy. For example, Englebert defines legitimacy as “the extent to which there is agreement about what constitutes the polity or the community that comprises the state” (2000, 8). Carment, Prest, and Samy claim that “legitimacy refers to the extent to which a state commands public loyalty to the governing regime, and to generate domestic support for that government’s legislation and policy” (2010, 89). Similar definitions are offered by Gilley (Reference Gilley2006) and McMann (Reference McMann2016).

There is less agreement, however, about how to measure state legitimacy. Englebert measures legitimacy as a dichotomy: States that have established themselves within their territories based on historical precedence are legitimate (2000, 125–33). Carment, Prest, and Samy favor a continuous variable and build an index based on institutional duration, regime type, human rights protection, and environmental protection (2010, chapter 3). Gilley’s measure involves public approval data. McMann assesses legitimacy with on-the-ground interviews. Englebert’s measure does not vary for any given state, whereas the others vary over time. Despite different measurement strategies, there is considerable overlap. Correlations between the empirical measures hover between r = 0.4 to r = 0.6. There is a large literature on conceptual and operational definitions of legitimacy, much debate among scholars, and yet some consistency across measures.Footnote 2

Having defined the central concepts, I now present my framework.

The Framework

My framework provides a new way to think about the subjects of IR research by nesting them within the state-making process. It encourages IR scholars to contextualize their studies of discrete events by connecting them with earlier events in each state’s history. Past events matter because they affect how much capacity and legitimacy a state currently has, which influences its opportunity and willingness to be involved in new events by affecting their likely outcomes. This framework also motivates new theoretical arguments about the comparability of different actions states can take to increase their capacity and legitimacy. Finally, it highlights some threats to valid inference that plague existing IR research.

As a first step in applying the framework, think of each state’s existence as the length of time between birth and death. Every state’s goal is to maximize this duration by enhancing survival. What helps them do so? My reading of the state-making literature suggests that capacity and legitimacy are the important means to extend the life of the state. Capacity and legitimacy are complements because high-capacity states govern better, which enhances their legitimacy, and legitimate states enjoy an easier time governing and extracting resources.

SM research focuses on the efforts of states to increase their odds of survival. If they are successful, they persist longer; if they are unsuccessful they are less likely to persist. Unsuccessful states either die or suffer spells of state failure. This raises an important question about what influences capacity and legitimacy. Bellicose theory suggests that capacity increases with war (presumably especially with war victories) and with preparation for war (Tilly Reference Tilly1990). Economic development is similarly associated with greater capacity; this is the underlying assumption in Fearon and Laitin’s (Reference Fearon and Laitin2003) argument about insurgency and civil war. Good governance likely enhances legitimacy or at least the acceptance of a state as “legitimate.” Gibler finds that citizens acquiesce to the greater centralization of power when their state is threatened by territorial rivals, specifically mentioning “broad support for the executive” (Reference Gibler2012, 89). Thus states can pursue multiple security and economic policies to enhance their capacity and legitimacy and thereby prolong their existence.

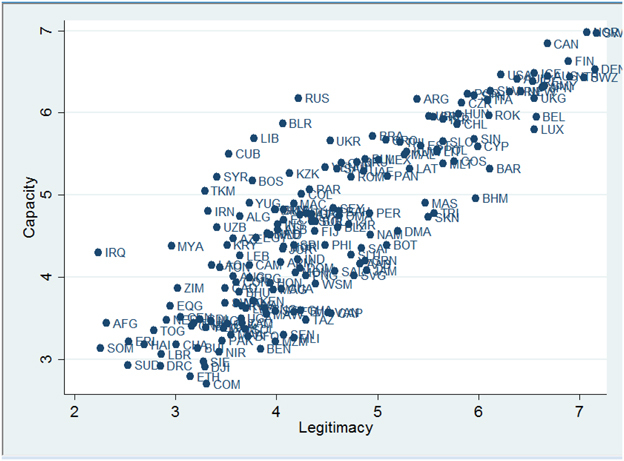

I conceive of capacity and legitimacy as axes of a coordinate plane, as in figure 1. The vertical axis represents higher levels of capacity, whereas the horizontal axis represents greater levels of legitimacy. At the origin capacity and legitimacy are at their minimums, and probably that state is dead (e.g., Somalia). At the northeast corner, capacity and legitimacy are both at very high levels, and that state likely is very secure against threats of death (e.g., Canada). Moving from the origin toward the northeast along the 45° diagonal we find state failure (e.g., Zimbabwe), then stagnation (e.g., Lebanon), and then stability (e.g., Singapore) as we move to higher and higher levels of capacity and legitimacy.

Figure 1 Capacity/legitimacy values, 2006

In addition to portraying capacity and legitimacy as axes in a coordinate plane, figure 1 presents data about capacity and legitimacy scores for 181 states in 2006, as defined by Carment, Prest, and Samy (2010, 91–97). I use Carment and colleagues’ scores for these variables because they are available for the largest number of states, but a similar pattern emerges with other measures. I do not suggest these scores are definitive, and indeed there is wide disagreement among scholars about how to measure these variables; instead I use them illustratively to explicate my framework. As seen in figure 1, most states cluster around the 45° diagonal, because as mentioned earlier, capacity and legitimacy are complementary.

Describing capacity and legitimacy as complements is common in existing research (Englebert Reference Englebert2000; Hegre and Nygård Reference Hegre and Nygård2015; Jackman Reference Jackman1993). Yet off-diagonal instances are possible. The southeast corner might include “claimant” states enjoying great legitimacy among the population but barely controlling territory. Similarly, the northwest corner might include a colonial state or a foreign occupation that very ably controls territory, but that is seen as entirely illegitimate by the people living there. Figure 2 presents a property space in which capacity and legitimacy are represented as having only high or low values rather than as continuums.

Figure 2 Capacity/legitimacy property space

A comparison of figure 1 and figure 2 suggests that states only rarely find themselves far off the diagonal. Consider the states in figure 1 farthest from the 45° diagonal. Iraq in 2006 was sustained by enormous aid and military intervention by the United States. Almost all of that capacity, however, was transferred to Iraq by the United States, and Iraq’s legitimacy score was among the world’s lowest. Another group of authoritarian states— Russia, Belarus, Libya, and Syria—cluster above the diagonal. These states rely on coercion to maintain themselves, and disaster has struck both Libya and Syria since 2006. Moving below the diagonal there are no distant outliers, although an interesting group of island republics enjoy higher legitimacy than capacity (Bahamas, St. Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines). Perhaps island republics can persist with low capacity because they have small populations from which very few challenges may emerge. The expectation from figure 2 is that off-diagonal states face greater threats (above the diagonal), although higher capacity may help these states resist those threats, or although they face few threats because of high legitimacy (below the diagonal), they have difficulty responding to any threats that do arise. The takeaway from figure 2 is that state survival is enhanced by increasing both capacity and legitimacy. States low in both are failed states at best, whereas states high in both are secure; off-diagonal state existence is tenuous. Survival dictates efforts to increase both.

The framework helps characterize how IR might best begin to incorporate the process approach suggested by SM research. Past events within a state’s history influence future events through their effect on capacity and legitimacy. If the past event was a war the state won, capacity and legitimacy likely increase, which makes the expected outcomes of future wars more favorable. This could make future war more likely as the more capable state assails additional foes. Alternatively, it could have the opposite effect if the state’s potential adversaries also observed that increase in capacity and legitimacy, making them more likely to acquiesce to the more capable and legitimate state’s demands. Either way, the state should be less likely to experience state failure or state death.

The framework also draws attention to nonviolent state policies such as developmental strategies. The successful execution of a strategy of export-led growth increases a state’s capacity by expanding the economic base from which it extracts taxes. In most successful instances of export-led growth, the regime makes a transition to democracy, which likely increases the state’s legitimacy as well. This also makes subsequent policies more likely to succeed, which should also increase the state’s odds of survival.

The framework has two main implications. First, past events and outcomes influence future events and outcomes. This implication stems from the framework’s assumptions about survival, capacity, and legitimacy. Second, events within a state’s SM process matter in terms of their effects on capacity and legitimacy. This is best seen in the discussion of figure 1 and figure 2. A methodological point follows from each implication. With respect to historical sequences, the failure to consider past behavior when studying present behavior threatens inferences either through spuriousness (the past behavior explains both the present behavior and its outcome) or through selection bias (the present instances are an unrepresentative sample of all possible instances, and thus inferences are biased positively or negatively). The second methodological point recognizes that if states choose military, economic, diplomatic, and political strategies based on expectations about how they will affect capacity and legitimacy, then they are either complements or substitutes. Ignoring this interconnection among survival strategies risks introducing omitted variable bias at the minimum and, depending on how decisions are made about these substitutable or complementary survival strategies, risks introducing endogeneity bias and violating the assumption of the independence of irrelevant alternatives.

Before exploring these implications in more detail, I clarify briefly how SM research motivates the framework. SM research is rarely expressed as being about a process, nor do most SM researchers explicitly emphasize capacity and legitimacy (though many do). Nevertheless, I argue that implicitly most SM research describes a process, and central to that process, regardless of the specific argument each SM researcher advances, are capacity and legitimacy. Thus, when Tilly (Reference Tilly1990) writes about the reduction from hundreds of independent states in Europe a thousand years ago to the few dozen now populating the continent, he is describing a process. Central to his process is war, which matters in his theory because it forced states to extract resources from their populations; those resources either increased the state’s capacity to carry out its task or some other state conquered and absorbed it. Spruyt (Reference Spruyt1994) modifies Tilly’s argument primarily by stressing the economic efficiency that a specific type of state—the sovereign territorial state—enjoyed in managing long-distance trade. Spruyt’s modification weaves into Tilly’s focus on war and taxation the contribution of wealth created by successfully managing economic exchange, which increased the territorial state’s capacity.

Unlike Spruyt, Centeno does not modify bellicose theory: instead he rejects its applicability to Latin American state-making outcomes. Because Latin America arose relatively late compared with Europe, external interventions by Europeans and by the United States prevented many wars from breaking out in Latin America. Centeno writes, “These external police may have prevented much bloodshed, but they may also have locked regions into political equilibriums unsuited for further institutional development” (2002, 17). By restricting Latin America to limited wars, the foreign interventions resulted in weak and indebted states. The resulting weak and indebted states were low capacity and did not govern all of their recognized territory. Those interventions also contributed to illegitimate states that are unable to mobilize a wide base of support. Herbst (Reference Herbst2000) identifies low population density as a reason why bellicose theory does not help us understand state-making outcomes in Africa, but he too sees foreign intervention (particularly the colonial experience) and a lack of wars as resulting in low-capacity and illegitimate states in Africa. This is a nonsystematic summary of SM research, but it covers much ground and clarifies the implicit process orientation of state-making research while plausibly indicating where in that process capacity and legitimacy matter. It is also reasonably representative of omitted scholarship.Footnote 3

A Closer Look at the Framework’s Implications

As indicated earlier, the framework encourages IR scholars to look for historical legacies within state experiences. A state’s odds of survival are influenced by what has happened in the past. Failure to consider the legacy of past events and outcomes on present events and outcomes raises risks of selection bias or spuriousness. The framework also encourages IR scholars to think of what states do as having been chosen from a portfolio of possible choices they might have made and thus to consider military, economic, diplomatic and other policies as potential substitutes or complements. Failure to consider these complementarities risks missing connections across currently disparate research programs; for example, scholars investigating when states go to war operate largely independently from scholars investigating why states choose a given developmental strategy. I develop each implication in turn.

Past Events and Outcomes Influence Present Events and Outcomes

The framework depicts each state’s past events as influencing present events by affecting levels of capacity and legitimacy. Successful war-fighting or developmental policies increase capacity and legitimacy and either make subsequent events more likely or influence their likely outcomes. Cumulatively the outcomes of past events influence how long the state persists. Importantly, influences on survival can be found both before birth and after death: Pre-birth experiences may affect the state’s initial endowment of capacity and legitimacy and also may influence the endowment of any successor state.

Research on colonial and birth legacies illustrates how a state’s pre-independence or initial experience influences its post-independence behavior. How might we think about pre-birth influences on subsequent state experiences in IR research? Existing scholarship provides examples. Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001) investigate how colonial experiences influence post-independence economic performance, and Bernhard, Reenock, and Nordstrom (Reference Bernhard, Reenock and Nordstrom2004) consider how colonial experiences influence the duration of democracy in former colonies. These studies and others similar to them show how the pre-birth experiences of states influence their subsequent behaviors. Returning to the framework, states with positive colonial legacies might have greater wealth or a more stable democracy, which would correlate with greater capacity and legitimacy; thus such states would begin independence farther to the northeast in figure 1, and thus have greater odds of continued survival. Birth legacy thus connects how states came into existence with subsequent events and outcomes.

Birth types differ in terms of whether they are internally mobilized or externally imposed. Internally mobilized births such as successful secessions or militarized decolonization struggles are more likely to occur when the emerging state has the capacity or legitimacy or both to prevail in its struggle for independence. In recent research Jeff Carter and I show that states enjoying greater capacity and legitimacy at birth are more likely to fight and to win wars (Lemke and Carter Reference Lemke and Carter2016). Similarly, Carter, Bernhard, and Palmer (Reference Carter, Bernhard and Palmer2012) find that states arising from successful revolutions are better able to mobilize populations and resources and are more likely subsequently to win any wars they fight. Additionally, Reference Carter and LemkeCarter and Lemke (n.d.) show that birth legacy also has an important influence on state failure. Similarly, Maoz (Reference Maoz1989) argues that states that emerged from wars or revolutions experience higher levels of conflict as new states, whereas states that emerged peacefully initially have low levels of conflict that rise to average levels over time. Other than these works, few conflict or state failure studies consider that how states came into existence may influence their subsequent conflicts or political stability. Scholars researching these topics have missed how earlier events and outcomes on a state’s time line can influence later ones. They are specifically missing the point that good birth states begin life farther to the northeast in figure 1 and thus have better odds of survival.

Turning to the other end of a state’s existence, states that fail to prosper wither and sometimes die. Some lose control of their territory and are no longer states. That withering process is state failure, and the endpoint is state death. Failing states are not yet dead, however, because while failing they still control some territory and provide some governance. In addition, some failing states recover and stave off death.

There is a large literature on state failure. Iqbal and Starr (Reference Iqbal and Starr2016) find that civil wars, interstate wars, internal unrest, and instability all increase the risk of state failure, whereas wealth decreases that risk. Perhaps oddly, they do not differentiate among conflict experiences—that is, they do not investigate whether victory in war (civil or interstate) makes state failure less likely than does defeat in war (or stalemate). Surely these variables have an influence on state failure, but because prevailing IR research practice ignores past events and outcomes when investigating present events and outcomes, such questions are not asked.

Moving from state failure to state death, Fazal’s (Reference Fazal2004; Reference Fazal2007) analyses do not incorporate variables representing the presence of wars or their outcomes. As with research on state failure, it would be useful to know whether victory makes death less likely and defeat makes it more likely. It is puzzling that such an analysis has not been undertaken. (Valeriano and van Benthuysen [Reference Valeriano and John van Benthuysen2012] replicate and extend Fazal’s work, but do not add war outcome variables.)

One disadvantage of omitting consideration of past events and outcomes from the study of current events and outcomes is that we fail to realize that well-established regularities widely reported in IR research may be spurious correlations. Lemke and Carter demonstrate that birth legacy influences civil and interstate war onset and outcomes, as well as state capabilities (2016, 501). More recently, they show that birth legacy also influences state failure (Reference Carter and LemkeCarter and Lemke n.d.). This means that well-known correlates of conflict (political stability and relative power) and conflict itself (both inter- and intrastate) are both correlated with the temporally prior variable of birth type. If these temporal sequences are causal, then well-known relationships in IR conflict research—between power and conflict and between political stability and conflict—are spurious. Similarly, Gibler (Reference Gibler2017) shows that the well-known relationship between dyadic parity and conflict onset is spurious, with both conflict and relative parity correlating with the prior variable of when and where states enter the international system. The relationship between parity and conflict is one of the most widely accepted relationships in IR conflict research, and that it is spurious is important news. It is hard to repair such potential inferential errors or even diagnose them without something like my framework.

This concern suggests an important way in which the framework can provide context to disparate IR findings and arguments. Specifically, we may need to incorporate sequencing into our estimation of effects to avoid selection bias. Lemke and Carter (Reference Lemke and Carter2016) achieve this with selection models, and Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001) use an instrumental variables approach. The framework suggests that other scholars should employ similar estimation techniques.Footnote 4 Alternatively, standard analyses could be accompanied by process-tracing case narratives. None of these methodological suggestions will eliminate the problems across all cases, and any estimation strategy involves assumptions that, when violated, introduce new problems. But IR scholars should at least give serious consideration to how they can better nest their analyses within the historical processes of state making.Footnote 5 The takeaway message is that major findings about conflict onset and outcome, state failure, and state death may all be spurious. The way to diagnose and treat such inferential threats is to self-consciously build the state’s historical process into our analyses.

Survival Strategies as Complements or Substitutes

Figure 1 and figure 2 illustrate how important it is for states to enhance their capacity and legitimacy. If the framework is valid, this means that, when states select policies about conflict, national development, and engagement with the international system, these policies matter in terms of their effect on capacity and legitimacy. Because capacity and legitimacy can be enhanced or degraded by any such policies, states are selecting policies that relate to each other along these two variables. Failure to maintain or increase capacity and legitimacy makes state failure or death more likely. This is an important disciplining effect on states, so surely they learn to select policies carefully. Doing so requires considering whether “this” policy is best in “this” situation. Another way to think about state policy selection then is to see it as states choosing a portfolio of policies from all the available options. Portfolio options are substitutes or complements, although very little IR research conceives of conflict, development, and diplomatic policies as substitutes or complements.

The SM research that motivates my framework has long identified war and preparation for war as one type of tool with which states strive to prolong their existence. Generally, taxes are closely connected to war in such arguments, because war (or the preparation for it) requires collecting more taxes, and failure to collect enough taxes renders states ill prepared for war. Tilly’s bellicose theory is the exemplar (1990; but see also Carneiro Reference Carneiro1970; Hui Reference Hui2005; Rasler and Thompson Reference Rasler and Thompson1989; Strayer Reference Strayer1970; Taylor and Botea Reference Taylor and Botea2008), and it clearly identifies the “test” of preparing for and succeeding at war as contributing to the capacity of successful states.

A problem arises for small or weak states because they are vulnerable to conquest by larger and stronger states. Such states must devise some means of increasing their odds of survival while having little or no ability to capture resources or population from other areas. Faced with this dilemma, and the evident survival of so many small and weak states, it must be the case that states diversify their portfolio of survival strategies, preparing for and waging war sometimes but also pursuing other strategies either simultaneously or alternatively.

Some SM studies engage the literature on strategies of economic development as a survival strategy (e.g., Waldner Reference Waldner1999). Greater economic production is valuable for survival. Necessarily then, states must care about development or they face a tenuous future. Similarly, diplomacy and the formation of alliances can also be conceptualized as survival strategies. A state might prevent (or foment) a war through diplomacy or use diplomacy to enhance the odds of victory in wars it fights through forming alliances and preventing enemies from gaining allies. A state skilled in diplomacy can improve its odds of victory by isolating its targets, denying them allies, and then attacking and conquering them. In these ways diplomacy and alliance politics can be complements to war fighting or even substitutes for it.

Another type of survival strategy, nation building, encompasses both the creation of a national identity and of a consistent set of standards regulating life within the state. The development of a national identity, of nationalism, or patriotism helps people identify more closely with the state. This enhances legitimacy and makes the population easier to govern. Nation building in the sense of the establishment of a consistent set of standards regulating life within the territory is also beneficial because consistent standards lower governance costs, which enhances state capacity. Thus, nation building increases both legitimacy and capacity. Thinking about efforts to enhance nationalism or to standardize life within a state as complements to or substitutes for other survival strategies is a promising area for future IR theorizing. For example, Sambanis, Skaperdas, and Wohlforth (Reference Sambanis, Skaperdas and Wohlforth2015) explicitly combine war making and nation building within one formal model. Efforts like theirs are particularly appealing for scholars adopting the framework.

What I have been calling survival strategies in this section are broad policies pursued by states to move toward the northeast corner of figure 1. What matters is not the specific type of policy chosen, but rather whether it enhances capacity and legitimacy. Each type of survival strategy is the subject of a reasonably large but usually independent research subspecialty within IR. But it certainly makes sense, as the framework implies, for each state to build a portfolio of policies in hopes of sustaining or enhancing capacity and legitimacy, thereby prolonging its survival. If so, it is likely that the makeup of portfolios will vary from state to state depending on their specific contexts. Some will favor investments in military policies, others in commercial/economic policies, and still others in diplomacy, but most will favor mixes of strategies of varying proportions. All of this suggests that the composition of portfolios is predictable, and it should prove useful to develop arguments about when different mixes will be more or less attractive to different states.

Testing such new theories will require IR scholars to take seriously the complementarity or substitutability of different portfolio elements. A decade or more ago, foreign policy substitutability was important in IR research design discussions (Clark and Reed Reference Clark and Reed2005; Most and Starr Reference Most and Starr1989, chapter 5), but it enjoys far less attention now. Perhaps one reason why research effort has declined is that, except for the two-good theory of foreign policy (Palmer and Morgan Reference Palmer and Clifton Morgan2006), few theories took substitutability seriously. Theories of survival strategy substitutability, inspired by the framework, could breathe new life into this promising research tradition.

Subsidiary Implication: Domestic and International Are Related

Building on the previous implication, it becomes clear that many steps taken to advance foreign policy goals are related to, and sometimes are the same as, steps taken to advance domestic policy goals. The framework is consistent with the complementarity of domestic and foreign policies if both matter because of their implications for capacity and legitimacy. If so, then one useful change IR researchers might adopt is to recognize that theories about why some foreign policies are chosen might also help us understand why analogous domestic policies are chosen.

For example, according to the framework the following scenarios are equivalent: (1) a state is menaced by foreign foes who want to conquer the state, and (2) a state is menaced by internal foes who want to supplant the state or break it into pieces. Scenario #1 is traditionally seen as a quintessential instance where IR arguments apply. Appropriate responses include power maximization, immediate deterrence, alliance formation, or even preventive attack. In contrast, Scenario #2 is traditionally seen as outside IR’s concerns, as instead an instance where comparative politics should offer explanations. Not surprisingly, comparative scholars have complied with that expectation. The literature on coup-proofing is one response. One form of coup-proofing is the creation of a special force to protect the leader from the rest of the military and defend against and deter coup attempts. Deterrence has a long tradition in IR theorizing. However, nowhere in the coup-proofing literature is there any application of IR theories of deterrence or explicit discussion of their implications for deterring domestic threats. Why? Because traditionally IR is about foreign threats. These connections have not been drawn because no one has thought to draw them. I expect that applications of IR deterrence theories to internal threat reduction will prove useful. The impact of Walter’s (Reference Walter2006) implicit deterrence argument about secession suggests we should try to develop explicit deterrence arguments. Another promising avenue is the IR conflict literature on alliances. A few domestic conflict studies feature it to motivate their analyses of alliances among militant groups within states (Bapat and Bond Reference Bapat and Bond2012; Christia Reference Christia2012; Lemke Reference Lemke and Palmer2008). Elsewhere I write of “intra-national IR,” encouraging exploration of instances where theoretical cross-fertilization from international politics to domestic politics exist (Lemke Reference Lemke2011). The framework encourages such conscientious cross-fertilizations.

The complaint that the dichotomy between foreign and domestic is artificial is a perennial one. Decades ago Milner (Reference Milner1991) renewed a line of argument that Alger (Reference Alger1963) had developed nearly 30 years before that. The novelty of my framework is that it presents more specific suggestions about how to breach the divide between the study of domestic and international politics.

Conclusions

The new framework inspired by SM research provides a conceptualization within which to reenvision much IR research. It focuses on cross-temporal connections in which past events and outcomes influence subsequent events and outcomes. It unifies consideration of many state behaviors by evaluating how they influence capacity and legitimacy. These behaviors are central because they are the sources of state survival. They are also the state behaviors long of interest to IR researchers.

A skeptical reader might wonder how accurate it is to argue that states pursue capacity and legitimacy because they are survival enhancing. If states rarely die, why bother to undertake difficult strategies like nation building? Stagnant states in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere in the postcolonial world bolster such objections. But it may be that the failure by leaders of such states to increase capacity and legitimacy explains why so many of them are replaced violently. Consider also what, other than the benefits of capacity and legitimacy, might explain why so many rebel groups spend considerable resources on governance and diplomacy (Arjona, Kasfir, and Mampilly Reference Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015; Coggins Reference Coggins, Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015; Huang Reference Huang2016a, Reference Huang2016b; Stewart Reference Stewart2018). Rebels must believe that efforts to enhance capacity and legitimacy will prolong their independent existences by securing them support, perhaps including recognition, from other states.

If IR scholars adopt my framework, IR research will move in new directions. It will increase its attention to temporal connections across events. It will focus on the substitutability and complementarity of survival strategies. It will deemphasize the foreign–domestic distinction. These will be big gains, but achieving them will not be easy. They require thinking carefully about temporal dependencies across each state’s existence and developing arguments and likely data about the comparability of survival strategies. The gains will be easier to achieve if IR scholars use the framework to develop new theories, understanding that it is not itself a fully fleshed-out theory; it does not provide a complete causal account of how independent variables cause dependent variables. Instead, it is a framework to motivate more specific theoretical arguments about particular independent and dependent variables. It is an invitation to theory, rather than a theory itself.

And yet, even at the rudimentary level presented here, the framework offers specific new areas for IR research. For example, by considering how past events and outcomes influence current events and outcomes, hypotheses emerge about war outcome and the likelihood of state failure and state death. In addition, the focus on capacity and legitimacy renders comparable inter- and intrastate behaviors of states, justifying applications of standard IR deterrence theory to the analysis of state efforts to deter opposition groups from rising in revolt. The framework also motivates some specific alterations to statistical estimation in IR, promoting increased attention to selection or causal inference models like those relying on instrumental variables, as well as multinomial or other estimators useful for teasing out relationships among complements and substitutes.