Introduction

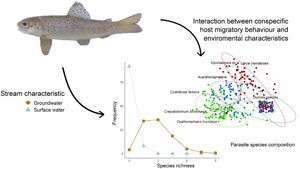

Parasite communities and species distributions are influenced by multiple abiotic and biotic variables that lead to their non-random distribution in space (Crofton, Reference Crofton1971; Ostfeld et al., Reference Ostfeld, Glass and Keesing2005). Among the biotic factors, host vagility and behaviour can influence the dispersal of parasites and their distribution. For instance, a migratory host may facilitate the spread of a parasite into new environments where the parasite might encounter and infect a novel host population (e.g. Figuerola and Green, Reference Figuerola and Green2000; Altizer et al., Reference Altizer, Bartel and Han2011; Kutz et al., Reference Kutz, Checkley, Verocai, Dumond, Hoberg, Peacock, Wu, Orsel, Seegers, Warren and Abrams2013). On the other hand, migration may allow the host to escape parasitism by moving away from infection hotspots (e.g. Bartel et al., Reference Bartel, Oberhauser, de Roode and Altizer2011; Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Closs, Lill, Hicks, Herrmann and Kelly2012) and reduce the exposure of juveniles to parasitism by removing infected adult individuals from the area (e.g. Krkošek et al., Reference Krkošek, Gottesfeld, Proctor, Rolston, Carr-Harris and Lewis2007). A link between host migration and similarity in the parasite communities has been extensively documented in the literature. Parasites have often been used to trace the migratory behaviour of their hosts and discriminate host stocks in the sea, but rarely in freshwater (e.g. Carballo et al., Reference Carballo, Cremonte, Navone and Timi2012; Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Tonkyn, Yarrow and Johnson2016; Irigoitia et al., Reference Irigoitia, Incorvaia and Timi2017; Canel et al., Reference Canel, Levy, Soares, Braicovich, Haimovici, Luque and Timi2019). However, migration is a heterogeneous phenomenon, varying both between and within species. Partial migration is common amongst migratory species, particularly in fish, where just a fraction of a population migrates and the remainder stay resident (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Skov, Hulthén, Brodersen, Nilsson, Hansson and Brönmark2012). Whereas previous work has focussed on how migratory individuals within migratory populations are affected by parasitism, we know much less about how the migratory life style of some individuals may influence parasite infections of non-migratory individuals of the same populations.

Parasite infracommunities of freshwater fish are generally considered stochastic and unpredictable in nature, and represent an independent assortment of parasites assembled from a pool of regionally available species (e.g. Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Broughton and Hine1978; Esch et al., Reference Esch, Kennedy, Bush and Aho1988; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy, Esch, Bush and Aho1990; Guégan et al., Reference Guégan, Morand, Poulin, Thomas, Renaud and Guégan2005). Abiotic factors at the local scale can act as filters of the pool of organisms found at higher scales (Poff, Reference Poff1997). For instance, the physical and chemical properties of the water can vary substantially depending on the source of the water in the stream and lead to changes in the free-living and parasitic faunal communities (Ward, Reference Ward1994). In surface-water-fed streams, water originates mostly from snow melting and rain in the mountains. These streams represent variable environments with low nutrients in the water and little vegetation. These factors lead to a poorer macroinvertebrate community and lower abundance of species than in groundwater-fed streams (Ward, Reference Ward1994). The latter have a large content of nutrients and elements washed from the substrate, like nitrogen, and support more diverse communities of species than surface water streams. In general, the richer and more abundant the macroinvertebrate community, the more likely it is to support diverse parasite species (e.g. Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Bush and Aho1986; Sures, Reference Sures2004; Johnson and Heard, Reference Johnson and Heard2017), in particular heteroxenous ones that require multiple host to complete a single generation (e.g. Marcogliese, Reference Marcogliese1995; Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Bunnell and Sukhdeo2007). Abiotic processes like the unidirectional water flow in streams can structure free-living and parasite populations and communities by favouring a downstream dispersion of small organisms, thus increasing their concentration downstream (Blasco-Costa et al., Reference Blasco-Costa, Koehler, Martin and Poulin2013; Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Knudsen, Blasco-Costa, Dunn, Hytterod and Hansen2018; Tonkin et al., Reference Tonkin, Altermatt, Finn, Heino, Olden, Pauls and Lytle2018). Furthermore, the environmental conditions of streams may affect both phenotype and foraging ecology of the resident hosts (Dermond et al., Reference Dermond, Thomas and Brodersen2018, Reference Dermond, Melián and Brodersen2019a, Reference Dermond, Sperlich and Brodersen2019b). Hence, environmental conditions that affect the hosts directly or indirectly will have a cascading effect on the prevalence and abundance of parasites, and on the diversity of parasites infecting them (MacKenzie et al., Reference MacKenzie, Williams, Williams, McVicar and Siddall1995; Marcogliese and Cone, Reference Marcogliese and Cone1997).

In this study, we use brown trout (Salmo trutta, L.) and its parasite community as a model system. Adult brown trout can have migratory or sedentary habits and the occurrence of these behaviours varies among populations (Klemetsen et al., Reference Klemetsen, Amundsen, Dempson, Jonsson, Jonsson, O'Connell and Mortensen2003). However, young non-migratory brown trout populations should harbour a parasite community representative of the local parasite fauna available in the stream. Fish from streams situated in geographical proximity to each other (flowing into the same lake) must be exposed to a similar regional pool of parasites in the lake available for recolonization of the streams with returning migratory adult brown trout (Barger and Esch, Reference Barger and Esch2001). We hypothesize that young trout in streams with groundwater as main inflow and/or more migratory trout will harbour greater parasite diversity (species richness and composition), and more species with complex life-cycles than those in streams with mainly surface water inflow and/or less migratory trout. The aim of this study is to assess the contribution of the source of water in combination with the rate of migration of adult trout to the parasite alpha diversity and similarity in the species composition of infracommunities of young resident brown trout.

Material and methods

Study area and fish sampling

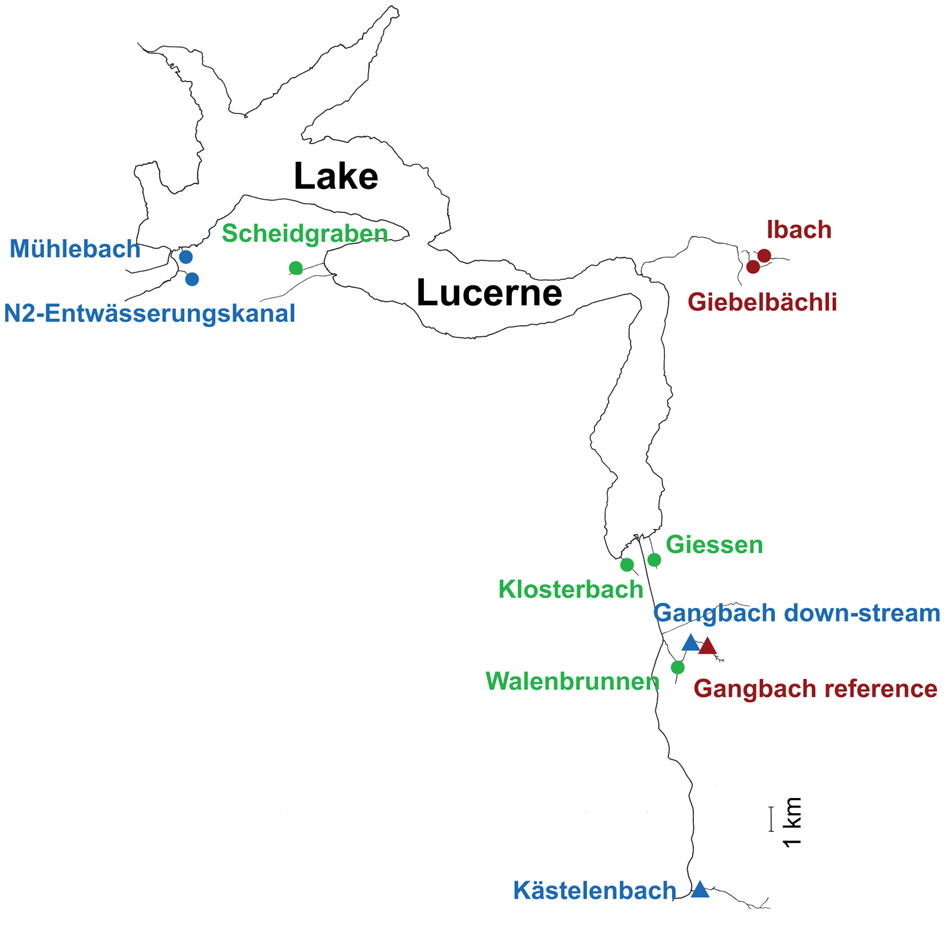

Eleven sampling sites located in 10 streams flowing into four sections of Lake Lucerne (Switzerland) were selected on the basis of previous data on trout partial migration (J. Brodersen unpublished data) and the type of watershed (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). In this system, migratory trout generally move from the natal stream habitat to the lake as juveniles in their 3rd or 4th year of life to increase growth, and after a variable number of summers in the lake, return to their natal streams to reproduce in sympatry with lifelong resident individuals (Dermond et al., Reference Dermond, Melián and Brodersen2019a). Fish communities in the streams are dominated by brown trout, with a minority of Cottus gobio (L.), Lota lota (L.), Esox lucius (L.) and Squalius cephalus (L.) recorded in some streams. At each of the 11 sites, 26−31 juvenile brown trout were collected in October 2016 (Table 1) by electrofishing using a backpack DC unit on a survey stretch ranging from 23 to 50 m. We selected juvenile brown trout with standard length of 68–123 mm (1−2-year old) in order to ensure that the fish had never migrated and to reduce the potential effects of host age on parasite acquisition. Thus, their parasite community should reflect the locally acquired species. Fish were euthanized using a high concentration of MS222 (Tricaine Methane-Sulphonate) (Popovic et al., Reference Popovic, Strunjak-Perovic, Coz-Rakovac, Barisic, Jadan, Berakovic and Klobucar2012; Dermond et al., Reference Dermond, Sperlich and Brodersen2019b). Then, all fish were weighed and measured before freezing at −20°C until parasitological examination. In addition, the trout migration rate for each stream was estimated using dual loop-antennas that recorded the transit of individually PIT-tagged fish between the lake and the streams in 2015 and 2016 as describe in Dermond et al. (Reference Dermond, Melián and Brodersen2019a). Total nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations were measured from 100 mL of filtered water samples from each locality using a continuous flow analyser Skalar San++ (Skalar Analytical) and following standard methods (APHA, 1998; DEV, 2016).

Fig 1. Map of Lake Luzern with the location of the 11 sampling sites situated in 10 streams. Sampling sites are colour-coded according to the category of migration rate (green, high migration; blue, medium migration; red, low or no migration) and the icons (circle, groundwater; triangle, surface water) correspond to the type of water source of the stream (see Table 1 for additional characteristics of each stream). Scale bar = 1 km.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 11 sites in the studied streams

a This migration rate was estimated based on observed amount of returning adults in the spawning period.

Parasite collection and morphological identification

Fish were thawed and dissected under a stereomicroscope and all the organs and tissues were examined for metazoan parasites. Parasites were fixed in absolute (99%) ethanol for molecular analyses, or in 70% ethanol for whole-mounts (Cribb and Bray, Reference Cribb and Bray2010; Justine et al., Reference Justine, Briand and Bray2012). All specimens used for the morphological analyses and DNA extractions are held at the collection of the Natural History Museum of Geneva (accession numbers MHNG-PLAT-137204–MHNG-PLAT-137301). Morphological identification of the parasites was initially based on Moravec (Reference Moravec2004), and additional comparisons with the original descriptions were performed when needed.

Genetic analyses and molecular identification of the parasites

Molecular data were obtained from a subsample of specimens (a total of 39 specimens of 10 different morphotypes) for each prospective species to confirm their morphological identification. DNA was extracted using Chelex® in deionized water containing 0.1 mg mL−1 proteinase K. A partial fragment of the large ribosomal subunit (28S rDNA) was chosen as marker because it is broadly used to identify parasitic flatworms (Blasco-Costa et al., Reference Blasco-Costa, Cutmore, Miller and Nolan2016) and sequences are already available for several parasites of brown trout. The following primers were used for amplification of the 28S rDNA of trematodes and acanthocephalans, U178 (5′-GCA CCC GCT GAA YTT AAG-3′) and L1642R (5′-CCA GCG CCA TCC ATT TTC A-3′) (Lockyer et al., Reference Lockyer, Olson and Littlewood2003); and for cestodes, LSU5F (5′-TAG GTC GAC CCG CTG AAY TTA AGC-3′) and 1500R (5′-GCT ATC CTG AGG GAA ACT TCG-3′) (Littlewood et al., Reference Littlewood, Curini-Galletti and Herniou2000; Olson et al., Reference Olson, Cribb, Tkach, Bray and Littlewood2003). In addition, a partial fragment of the small ribosomal subunit (18S rDNA) was amplified for the nematodes since it is the most common marker used for this group (Černotíková et al., Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011); with the primers PhilonemaF (5′-GCC TAT AAT GGT GAA ACC GCG AAC-3′) and PhilPCRr0 (5′-CCG TT CAA GCC ACT GC ATT A-3′). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications were performed using a total volume of 20 μL containing 4 μL of DNA template, 2× MyFi™ Mix (Bioline France, France) and 4 μ m of each forward and reverse primers. The PCR amplification protocol for the 28S marker followed Blasco-Costa et al. (Reference Blasco-Costa, Balbuena, Kostadinova and Olson2009) and for the 18S followed Černotíková et al. (Reference Černotíková, Horák and Moravec2011). After verification of single band PCR products via electrophoresis, amplicons were purified with a mix of exonuclease I and thermosensitive alkaline phosphatase enzymes (Werle et al., Reference Werle, Schneider, Renner, Volker and Fiehn1994). Purified amplicons were sent to Macrogen Europe (Amsterdam, Netherlands) for sequencing from both strands with the same PCR primers used for amplification and an additional internal primer for the 28S fragments, L1200R (5′-GCA TAG TTC ACC ATC TTT CGG-3′) (Littlewood et al., Reference Littlewood, Curini-Galletti and Herniou2000).

Sequences were assembled and inspected for errors in Geneious ver. 8.1.9 (Kearse et al., Reference Kearse, Moir, Wilson, Stones-Havas, Cheung, Sturrock, Buxton, Cooper, Markowitz, Duran, Thierer, Ashton, Meintjes and Drummond2012) and submitted to GenBank (see accession number in Supplementary Table S1). Available sequences for taxa belonging to the same family/genus/species as our presumed taxa were obtained from GenBank and aligned together with our sequences to confirm species identification or refine the preliminary identification based on the morphology. In order to root the phylogenetic trees, a sister taxon outside the family was included for each alignment. Sequence datasets (newly obtained sequences and GenBank sequences for each target family) were aligned using default parameters in MAFFT (Katoh et al., Reference Katoh, Kuma, Toh and Miyata2005). The resulting alignments were visually inspected and the extremes were trimmed. Phylogenetic reconstructions were used to confirm the affiliation of our sequences to a species, genus or suprageneric taxon. We conducted phylogenetic analyses under maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) criteria. The model of nucleotide evolution general time-reversible model with the gamma-distribution among site rate variation (Γ) was applied to all analyses. ML analyses were conducted using RAxML ver. 8 (Stamatakis, Reference Stamatakis2006). All model parameters and bootstrap nodal support values (1000 repetitions) were estimated in RAxML. BI trees were constructed using MrBayes ver. 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al., Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, van der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Höhna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012), running two independent MCMC runs of four chains for 10 million generations and sampling tree topologies every 1000th generation. Burn-in periods were automatically set to 25 000 generations. RAxML and MrBayes analyses were carried out for each individual dataset on the public computational resource CIPRES (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Pfeiffer and Schwartz2011).

Dataset and statistical analyses

Infection descriptors including prevalence (number of infected fish with a particular parasite in percentage) and mean intensity (mean number of parasite individuals of a species per infected fish, MI) were calculated for each site (at the component community level as described by Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997). Taxa identified exclusively with the use of molecular data (a gorgoderoid gen. sp. metacercaria, Neoechinorhynchus sp. and Echinorhynchus sp., Streptocara incognita and a Cystidicolidea gen. sp.) were poorly represented in the parasite communities. Thus, no specimens were available for further morphological examination. Since the remaining not sequenced specimens could not be distinguished accurately to species/genus level, the ecological parameters (prevalence and mean intensity) were calculated for the nine taxonomic entities recognized on the basis of the morphology, the three acanthocephalan lineages were pooled together and the two nematodes from the digestive tract were also grouped (see results below). Statistical analyses were carried out on the parasite infracommunities of 337 fish specimens. The dataset included information on fish migration rates, water source of the stream and water properties (total phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations) for each stream site, in addition to the parasite species and their abundance in each fish. Fish migration rates correspond to outmigration of juvenile brown trout. It was calculated as the percentage of the mean number of tagged fish leaving the stream out of the total number of tagged fish per stream over 2 years (data originally collected in 2015 and 2016 by Dermond et al., Reference Dermond, Melián and Brodersen2019a). We expect that return migration rates are linearly related to outmigration percentages except for the streams classified as non-migration, where returning migration rates are zero due to the presence of a physical barrier that impedes upstream movement.

We estimated parasite alpha diversity at the sampling unit (here the infracommunity sensus Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997) using three different indices. Species richness (S) measured the number of different taxa present in the sample. Margalef's index D Mg from Clifford and Stephenson (Reference Clifford and Stephenson1975) is used as a simple measure of diversity that only takes into account the richness and total number of individuals in the sample. Jost-transformed Shannon entropy index is used as an advanced diversity index that includes the species richness, abundance and the evenness (it weights the taxa by their frequency and treats equally common and rare species) (Jost, Reference Jost2006). Differences in species richness and diversity across types of streams, migration regimes (as continuous variable) and nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations were analysed using generalized linear models (lmer4::glmer, ver. 1.1-21; Bates et al. (Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker, Walker, Christensen, Singmann, Dai, Scheipl and Grothendieck2019)) with a Poisson distribution and a negative binomial distribution (lmer4::glmer.nb), respectively, with stream as random factor.

To assess variation in species composition, the dissimilarity among the parasite infracommunities as a function of stream water source and fish migration (Krebs, Reference Krebs1999) was assessed by means of a non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination method. The zero-adjusted Bray−Curtis dissimilarity measure, which is not affected by the number of null values between samples, was used to perform the NMDS analysis (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Somerfield and Chapman2006). The dissimilarity matrix was calculated upon the abundance data for each parasite species in 337 fish infracommunities. To account for species absences in some infracommunities (zero-inflated data) a ‘dummy species’ was added to all communities (see Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Somerfield and Chapman2006) and only parasite taxa with a prevalence of at least 5% in the whole dataset were included to estimate the zero-adjusted Bray–Curtis dissimilarity measure. The significance of the predictor variables, i.e. type of stream water source, the rate of trout migration (as continuous variable) and their interaction, was tested with the Adonis function. These analyses were conducted with the package ‘vegan’ (Oksanen, Reference Oksanen2015) and ‘MASS’ (Venables and Ripley, Reference Venables and Ripley2002). All analyses were performed with the statistical software R version 3.004 (www.r-project.org).

Results

Parasite communities

Morphological and molecular analyses of collected parasite specimens allowed the identification of a total of thirteen parasite taxa (3 allogenic and 10 autogenic) from juvenile brown trout populations in streams around Lake Lucerne. Based on the morphology alone we recognized 10 taxa: the trematodes Crepidostomum sp. and Apatemon gracilis (Rudolphi, 1819) (metacercariae); the cestodes Cyathocephalus truncatus (Pallas, 1781), Proteocephalus sp., and Triaenophorus nodulosus (Pallas, 1781); the monogenean Gyrodactylus sp.; the acanthocephalan Echinorhynchus truttae (Schrank, 1788); and the nematodes Cystidicola farionis (Fischer, 1798) and two unidentified nematodes. Molecular data and phylogenetic analyses corroborate the morphological identification of the trematodes, cestodes, E. truttae and C. farionis (see Fig. 2), and highlighted the presence of three additional taxa: an unidentified metacercaria of the Gorgodeoidea (Trematoda); Neoechinorhynchus sp. and Echinorhynchus sp. (Acanthocephala; see Fig. 2). Molecular analyses also confirmed the identification of the specimens of Crepidostomum sp. as C. brinkmanni (Faltýnková et al. Reference Faltýnková, Pantoja, Skírnisson and Kudlai2020) (Fig. 2a). Sequences of juvenile specimens of Proteocephalus sp. formed a separate lineage among other sequences of Proteocephalus spp. (Fig. 2g), but did not match the sequence of P. longicollis available in GenBank from Coregonus lavaretus. Thus, the identification of these specimens to species level could not be achieved. One of the unidentified nematodes was molecularly assigned to Streptocara incognita (Gibson, 1968) (Acuariidae) and the other one as Cystidicolidae gen. sp.

Fig. 2. ML phylograms based on partial 28S rRNA gene sequences of parasite specimens from this study and selected sequences from GenBank: (A) Crepidostomum, with three sequences of taxa belonging to Allocreadium as outgroup; (B) the Diplostomatoidea, with sequences of Spirhapalum and Clinostomum as outgroup; (C) the Acrobothriidae, with two sequences of taxa belonging to the Gyrocotylidea as outgroup; (D) the Triaenophoridae, with two sequences of the eucestodes Grillotia erinaceus and Litobothrium janovyi as outgroup; (E) the Echinorhynchidae, with a sequence of Pseudoleptorhynchoides lamothei (Rhadinorhynchidae) as outgroup; (F) Neoechinorhynchus, with two sequences of Floridosentis spp. included as outgroup; (G) the Proteocephalidea, with sequences of Gangesia parasiluri and Acanthobothrium sp. serving as outgroup. ML phylograms based on 18S rRNA gene sequences of adult nematode and selected sequences from GenBank of (H) the cystidicolid nematodes, with the Physaloptea turgida and P. alata as outgroup. Bootstrap values are followed by Bayesian posterior probabilities above the branches. Full circles at the nodes illustrate high support (ML > 90, BI = 1) and empty circles illustrate moderate support (ML = 70–90, BI = 0.90–0.99). Scale-bars indicate the number of substitutions per site. Newly acquired sequences are marked in bold and 'n' indicates number of specimens sequenced. The asterisk indicates a partial sequence.

The majority of the species in the community belong to the Platyhelminthes (present in 70% of the fish), the Acanthocephala (in 23% of the fish) and the Nematoda (in 19% of the fish; see Table 2). Most parasites were found in the digestive tract (C. brinkmanni, Proteocephalus sp., C. truncatus, the three acanthocephalans and the two nematodes) and only few taxa/specimens were found in other organs like the skin (Gyrodactylus sp.), swim bladder (C. farionis), liver (e.g. T. nodulosus) or body cavity (A. gracilis and a metacercariae of the Gorgodeoidea).

Table 2. Infection parameters for the parasite community of brown trout populations from streams around the Lake Luzern, Switzerland expressed as prevalence of infection (PI) and the mean intensity of infection (MI)

WAL, Walenbrunnen, GIN, Giessen, KAR, Kärstelenbach, SGN, Scheidgraben, GAN, Gangbach down-stream, GAN_REF, Gangbach reference, KLO, Klosterbach, N2, N2-Entwässerungskanal, MUH, Mühlebach, IBACH, Ibach and GIEB, Giebelbächli.

a The migration rate in Kärstelenbach stream was not measured with an antenna. However, we assume that it goes in the category ‘some migration’. Indeed, this site is located above a barrier, which is only passed by some returning individuals and showed a low amount of lake trout spawning pits support this.

b Apatemon gracilis and an unidentified metacercaria of Gorgoderoidea, distinguishable only using molecular data, were analysed together.

c This group included three distinct taxa (Echinorhynchus truttae, Echinorhynchus sp. and Neoechinorhynchus sp.). The most common amongst the sequenced specimens was E. truttae and the two other taxa were only detected using molecular data. Thus, these three taxa were analysed together.

d This group included two distinct taxa (Streptocara incognita and Cystidicolidae gen. sp.). These two taxa were not common and were only distinguished using molecular data.

Species richness and diversity

Parasite species richness was significantly different between young brown trout in groundwater-fed streams and in surface water-fed streams (z-value = −3.185, P value = 0.001; Fig. 3). Species richness at the infracommunity level ranged from 0 to 6 parasite species in groundwater streams, against 0−1 species in fish from surface water streams. No significant differences in species richness were found in relation to the rate of fish migration, nitrogen or phosphorus concentrations in the streams. Parasite species diversity (Margalef's and Shannon entropy diversity) at the infracommunity level did not show significant differences for any of the variables considered.

Fig. 3. Parasite species richness in brown trout at the infracommunity level for each type of water source of the streams: (A) frequency distribution of the samples and (B) boxplot of mean species richness.

Out of the thirteen parasite taxa detected molecularly, only two taxa (C. brinkmanni and Gyrodactylus sp.) were shared amongst brown trout populations from both groundwater- and surface water-fed streams (Table 2). Three cestodes (C. truncatus, T. nodulosus, and Proteocephalus sp.), two digeneans (A. gracilis and the metacercaria Gorgoderoidea gen. sp.), two nematodes (C. farionis and an unidentified species, Nematoda gen. sp.) and three acanthocephalans (E. truttae, Echinorhynchus sp. and Neoechinorhynchus sp.) were only found in groundwater streams, whereas surface water streams were only colonized by Gyrodactylus sp. and C. brinkmanni (a single occurrence). Thus, almost all parasite species with complex life-cycles occurred in groundwater streams, regardless of the migration rate.

Parasite infracommunity dissimilarities among stream types

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling analysis based on zero-adjusted Bray–Curtis dissimilarity metrics showed segregation in the parasite communities of brown trout between both surface water- and groundwater-fed streams and rates of migrations, despite some overlap. The analysis had a stress value of 0.136, which fell within the accepted range (<0.2; Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, Somerfield and Chapman2006)). Both factors separately, migration rate and water source, were significant (Fig. 4, Adonis: migration rate F-value = 115.700, R 2 = 0.211 and P value <0.001; water source F-value = 104.740, R 2 = 0.191 and P value <0.001). The interaction between migration rate and water source was the main driver of the dissimilarity amongst the fish parasite infracommunities (Fig. 4; Adonis: F-value = 5.880, R 2 = 0.011, P value <0.001). These results were consistent irrespective of whether we considered migration rate as a continuous or categorical variable.

Fig. 4. Non-metrical multidimensional scaling biplot based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity among parasite infracommunities (N = 327). Infracommunities are colour-coded according to the migration category (green, high migration; blue, medium migration; red, low or no migration) and the icons (circle for groundwater; triangle for surface water) correspond to the type of water source of the stream. Ellipses regrouped 95% the parasite infracommunities of a particular migration rate category (coloured accordingly), indistinctly of the type of water source. The vectors with arrows in black indicate the contribution of each parasite taxa to the dissimilarity. Random jitter (0.1) was added to the plot to improve visualization of overlapped data points (mostly surface water infracommunities with no parasites). Asterisks represent P values lower than 0.001 for the Adonis test results.

Whereas most of the parasite infracommunities of brown trout from surface water-fed streams were aggregated on the bottom right side of the plot and characterized by the absence of parasites (i.e. ‘dummy species’ used for zero-inflated data), parasite infracommunities of brown trout from groundwater-fed streams appeared broadly spread out through the area of the biplot. Additional sub-clustering observed among the parasite infracommunities of groundwater streams (circles in Fig. 4) was captured by the variation in fish migration rates between streams. Thus, the graphical representation of the NMDS analyses and the Adonis results support heterogeneity in the parasite species composition and their abundance in the infracommunities as a function of both the source of water in the stream and the rate of returning conspecific migratory hosts from the lake. Vectors in the plot indicate that parasite infracommunities of fish from streams with high migration rates in groundwater-fed streams were dominated mainly by the presence of C. brinkmanni, C. truncatus and C. farionis (Fig. 4). Parasite infracommunities of trout in groundwater-fed streams with medium migration rates were mainly characterized by the presence of C. farionis and acanthocephalans as well as some C. brinkmanni and C. truncatus. In contrast, the parasite infracommunity composition of fish from groundwater-fed streams with low- or no migration was almost exclusively dominated by Gyrodactylus sp. and larval nematodes or by the absence of parasites.

Discussion

Overall our results showed that parasite infracommunities of young brown trout inhabiting groundwater-fed streams had higher species richness than those of trout from surface water-fed streams. Whereas at a finer scale, the interaction of both the source of water and conspecific migration rates explained the dissimilarities between parasite infracommunities composition of trout individuals from different streams. Thus, both environmental stream characteristics and conspecific migration rate determine the species composition and similarity of the parasite infracommunities of resident juvenile trout.

Most of the 13 parasite taxa present in brown trout were found at an adult stage (with the exception of T. nodulosus, A. gracilis and the unidentified gordoderoid metacercaria), which suggests that brown trout do not often serve as a vehicle for transmission of parasites to other predatory fish, birds or mammals from an early age. The majority of the taxa found in this study are common parasites of European trout (e.g. Joyeux and Baer, Reference Joyeux and Baer1936; Moravec, Reference Moravec2004) and already recorded in Switzerland (e.g. Dezfuli et al., Reference Dezfuli, Capuano and Congiu2002; Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Weiss, Stojanovski and Bachmann2015). However, C. brinkmanni represents a new parasite record for brown trout in continental Europe. So far, only Crepidostomum metoecus (Braun, 1900) and Crepidostomum farionis (Müller, 1780) were known to infect European salmonids. Crepidostomum brinkmanni has been recently described from brown trout and Arctic charr in Iceland (Faltýnková et al., Reference Faltýnková, Pantoja, Skírnisson and Kudlai2020) and was previously reported from mayfly in Norway (Soldánová et al., Reference Soldánová, Georgieva, Rohacova, Knudsen, Kuhn, Henriksen, Siwertsson, Shaw, Kuris, Amundsen, Scholz, Lafferty and Kostadinova2017). In addition, Echinorhynchus sp. may represent a putative new species or a different species yet to be described in salmonids. Indeed, Echinorhynchus sp. was found to differ from E. truttae (also found in this study) and E. salmonis (Müller, 1784) (previously recorded in European trout; Bauer and Skryabina (Reference Bauer, Skryabina and Bauer1987), Golvan (Reference Golvan1969) and Moravec (Reference Moravec2004)). In addition, the unidentified metacercaria belonging to the superfamily Gorgoderoidea and Streptocara incognita represent two new record for brown trout. The molecular characterization of specimens in addition to morphological identification in this ecological study allows us to recognize previously unknown diversity and improve the knowledge on host−parasite associations and distributions. Although we were unable to account quantitatively for these taxa in the ecological analysis, we are now aware of their presence. Our findings also highlight the need to continue to perform integrative taxonomic studies even in supposedly well-studied hosts and regions, like brown trout in central Europe.

Most of the above species were only occurring in young brown trout from groundwater-fed streams, resulting in significantly higher species richness in those streams than in surface water-fed streams. The latter were characterized by the absence of parasite infections or the presence of Gyrodactylus sp., a parasite with a monoxenous life-cycle, that is transmitted by contact or proximity between the hosts and whose transmission is favoured by high host densities. In our analyses, we were unable to control for host density as a determinant of the presence of this species in the different sites. The type of water source of a stream encapsulates large variation in water chemistry and nutrient availability, as well as other physical and geomorphological parameters that influence the aquatic systems and their animal communities (Ward, Reference Ward1994). In surface water streams, macroinvertebrate communities are depauperated and have low abundances (Ilg et al., Reference Ilg, Castella, Lods-Crozet and Marmonier2001). Indeed, surface water-fed streams in the area are almost devoid of snails, gammarids and coleopteran, but relatively dominated by Ephemeroptera (J. Brodersen unpublished data). Thus, fish may feed intensively on only a few taxa (e.g. Mejia et al., Reference Mejia, Baxter, Berntsen and Fremier2016), leading to low parasite richness and diversity. In contrast, fish have access to diverse macroinvertebrate prey in groundwater-fed streams (e.g. Kownacka and Kownacki, Reference Kownacka and Kownacki1972; Ward, Reference Ward1994), facilitating the acquisition of trophically transmitted parasites present in these intermediate hosts (e.g. Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Bush and Aho1986; Knudsen et al., Reference Knudsen, Amundsen, Nilsen, Kristoffersen and Klemetsen2007). Our results support that parasite communities in young trout from groundwater-fed streams are rich in species with complex life-cycles. Conversely, diversity estimates (using Margalef's index and the Shannon entropy index) at the infracommunity level failed to differ across different stream types. This result is likely due to the aggregated nature of the parasite infections, with most hosts having low infections and only a few carrying high values of diversity, which may require larger sample sizes in order to detect differences. Previous literature attributes this phenomenon to the low occurrences of parasite species in the infracommunities (e.g. Kennedy, Reference Kennedy, Esch, Bush and Aho1990 and references therein).

Prior knowledge on parasite infracommunities of freshwater fish (mostly focused on lakes) suggests that parasite infracommunities are generally stochastic and unpredictable in nature, and represent an independent assortment of helminth species present in the locality (e.g. Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Broughton and Hine1978; Esch et al., Reference Esch, Kennedy, Bush and Aho1988; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy, Esch, Bush and Aho1990). By using pre-migratory young trout, we ensured that their infracommunities reflect the parasite species available at the local scale. However, our results showed that similarity among parasite infracommunities could be predictable among streams by the interaction between water origin and the proportion of conspecific migratory individuals. This is the case at the small scale of our study, where all streams flow into the same lake. Particularly in groundwater-fed streams, where high variation in infracommunity similarity was detected, the presence of three taxa, C. brinkmanni, C. truncatus and C. farionis with medium to high abundances characterized streams with high migration rates of adult trout, whereas communities dominated by C. farionis, acanthocephalans and Gyrodactylus sp. or larval nematodes strengthen the similarity among parasite infracommunities of trout in streams with medium-to-low migration rates. Similarity among fish from all sites was mostly due to autogenic species, which dominated the parasite infracommunities of trout as in previous studies (e.g. Esch et al., Reference Esch, Kennedy, Bush and Aho1988). Thus, we concur with Kennedy (Reference Kennedy, Esch, Bush and Aho1990) in that the major determinant of helminth assemblages in brown trout (as for eels) are the environmental and habitat conditions, in particular here the water source. Indeed, the type of water source influences the macroinvertebrate community in the stream (Ward, Reference Ward1994), which in turn facilitates the transmission of parasites with complex life cycles. Furthermore, we endorse the ideas of Esch et al. (Reference Esch, Shostak, Marcogliese, Goater, Esch, Bush and Aho1990) regarding the role of host dispersal ability. Changes in the rate of migratory fish in the population can lead to changes in the similarity in composition and species abundances of the parasite assemblages at the infracommunity level of resident conspecifics. It is likely that, in the case of generalist parasites, differences caused by partial migration across populations will also affect the other non-conspecific host species in the community.

Host migration potential and colonization play an important role in structuring parasite assemblages in freshwaters (e.g. Esch, Reference Esch1977; Esch et al., Reference Esch, Shostak, Marcogliese, Goater, Esch, Bush and Aho1990; Loot et al., Reference Loot, Reyjol, Poulet, Simkova, Blanchet and Lek2007; Blasco-Costa et al., Reference Blasco-Costa, Koehler, Martin and Poulin2013; Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Knudsen, Blasco-Costa, Dunn, Hytterod and Hansen2018). Whilst, differences in parasite communities have been broadly applied to distinguish fish stocks in the sea (e.g. Criscione and Blouin, Reference Criscione and Blouin2004; Carballo et al., Reference Carballo, Cremonte, Navone and Timi2012; Canel et al., Reference Canel, Levy, Soares, Braicovich, Haimovici, Luque and Timi2019), the use of metazoan parasites as biological tags in freshwater migratory fish populations has been chiefly absent (but see Criscione and Blouin, Reference Criscione and Blouin2004). Although, geographically restricted, our results contribute to a better understanding of how variation in partial migration rates can drive the composition of parasite infracommunities of conspecific non-migrating fish in streams, and likely more broadly to other fish taxa in the case of generalist parasites. We hope future research will allow establishing the generality of the patterns detected here by investigating other partial migratory freshwater fish, across watersheds and larger scales. In addition, this knowledge can be used to inform managers about the health status of already threaten brown trout stocks, and design adequate measures to prevent parasite disease outbreaks in their natural and restocked populations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182021000780

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Brigitte Germann, Philip Dermond and co-workers from the Department of Fish Ecology and Evolution of Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, for their help during sampling and for providing estimates of migration rates; Mélanie Schneider, Janik Pralong and Gilles Roth from the Natural History Museum of Geneva for their technical help on fish dissections and illustrations. We are also grateful to Dr Alain de Chambrier and Dr Jan Brabec, Natural History Museum of Geneva, for their advice regarding the identification of cestodes. We also thank Prof. Jean Mariaux, Natural History Museum of Geneva and Cristina Llopis-Belenguer, University of Valencia, for their comments and advice on an early version of this manuscript. We would also like to express our appreciation to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments that helped us improve the manuscript.

Financial support

This study was supported by the Natural History Museum of Geneva, the Ville de Genève, EAWAG Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology and two Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) grants (31003A_153296 to Jakob Brodersen and 31003A_169211 to Isabel Blasco-Costa).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of Switzerland and our institutional guides on the care and use of wild animals, with the Cantonal authorization. No endangered species were used in the research conducted. All experimental procedures, including but not limited to capture and euthanization on wild fish were reviewed internally and externally by the Veterinary Office of the Four Cantons and authorized under research permit LU01/14.