INTRODUCTION

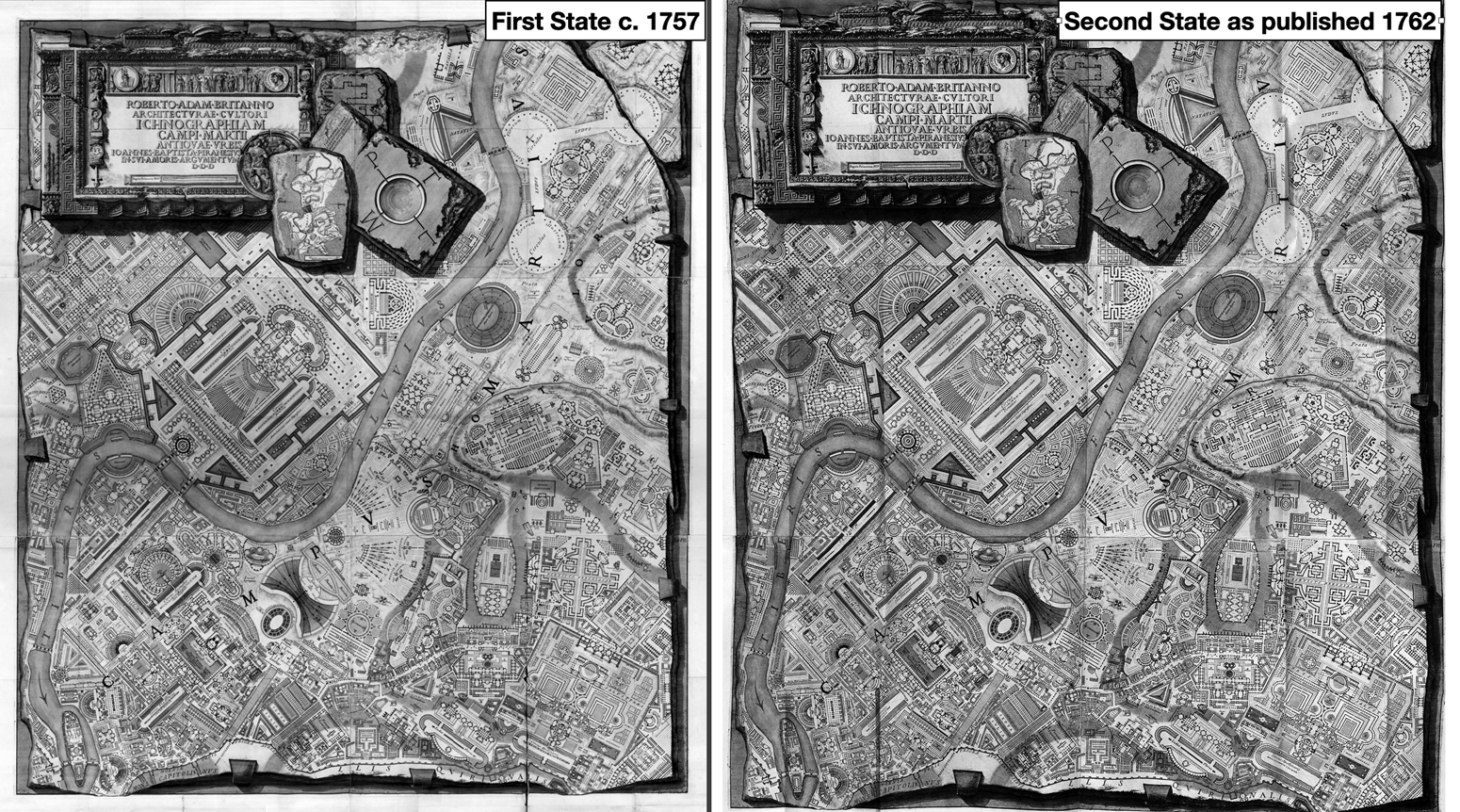

This essay introduces a previously unknown first state of Piranesi's Campus Martius plan (Fig. 1), one of the largest, most complex and most controversial of the Venetian architect's archaeological prints, and presents a hypothesis regarding the motivations behind the radical changes made from this first state to the second. These changes concern the architectural form of ancient circuses, in particular the starting-gates used by the chariots, known as carceres. The first state print will be compared with the more common second state, using the two versions at the British School at Rome [BSR]Footnote 2 and the copper plates conserved at the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica in Rome.Footnote 3 Both the prints examined here were part of the collection of Thomas Ashby at the BSR; the Library also holds a copy of the volume in which the plan is included, Campus Martius Antiquae Urbis (Rome 1762).Footnote 4

Fig. 1. G.B. Piranesi, Ichnographiam Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis, first and second states (Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

Before examining the two state prints and their antiquarian context, it is helpful to consider the variable status of perceived truth about the ancient world in the age of pre-scientific archaeology. Johann Joachim Winckelmann remains the ‘father of art history’ (Harloe, Reference Harloe2019) even though some of his interpretations have proved to be mistaken and he sometimes neglected existing scholarship to press ahead with his analyses of inscriptions or objects.Footnote 5 Piranesi's antiquarianism, despite the condemnation of his errors by those who looked critically at the Campus Martius plan, both during his lifetime and in our era (Lumisden, Reference Lumisden1797: 252–3; Connors, Reference Connors2011: 25–31), retains coherence, supported by the vast body of work he undertook in the analysis and recording of the structures and architectural ornament of ancient Rome and its environs. In the years before Piranesi started his four-volume Antichità Romane project (Piranesi, Reference Piranesi1756), there was constant antiquarian activity in the city that had created a vast hinterland of heterogeneous knowledge; what was judged as correct at one time could later easily be criticized as erroneous, as it often was. Archaeologists now, with the clarity of scientific method and the benefits of technology, are more confident in their conclusions about the ancient world which, however, remain open to interpretation. Piranesi employed antiquarian written and visual material, referenced ancient literary sources and, eventually, incorporated extant physical evidence into his interpretation of the appearance of the circuses, ancient structures which had a particular allure for early modern antiquarians and architects.Footnote 6 Piranesi changed his mind about the form, altering his plan and thus creating a second state. My hypothesis is that this change resulted from the acceptance of a specific piece of archaeological evidence, previously either deliberately ignored by or unknown to him.

Piranesi intended his Ichnographia Footnote 7 to be helpful to young or aspiring architects, to give them an expanded vocabulary of forms:Footnote 8

Le piante di tante fabbriche fra loro diverse, che vi si vedranno, e che hanno servito ad elevazioni [alle elevazioni] … serviranno agli studiosi dell'Architettura di norma nella posizione di qualunque edifizio che si proporranno di disegnare, o di costruire…

To an observer who turns to it in order to learn something about ancient Rome, it is the explosive invention of the plan that first strikes, not its potential usefulness to architects, archaeologists or antiquarians; its influence as a concept of a city neither actual nor historic is to be found in twentieth- and twenty-first-century theory and practice.Footnote 9 Yet it has revealed a wealth of precise detail from and reference to ancient Rome, one example being Piranesi's direct adoption of the graphical conventions from the Severan marble plan (Hornsby, Reference Hornsby, Bevilacqua and Hornsby2023: 149). Indeed, his friend and the dedicatee of the Campus Martius, the architect Robert Adam, whilst being aware of Piranesi's tendency to elaborate, took great advantage of the older architect's intimate knowledge of the ancient ruins and adopted many of the ideas from the Campus plan and volume, employing them consistently throughout his career:Footnote 10 the internal symmetry, the use of interlocking geometric shapes, the love of porticoes. He also borrowed specific arrangements of buildings for one of his own ambitious, unrealized projects (Hornsby, Reference Hornsby, Bevilacqua and Hornsby2023: 157).

1. THE TWO EXEMPLAR CIRCUSES

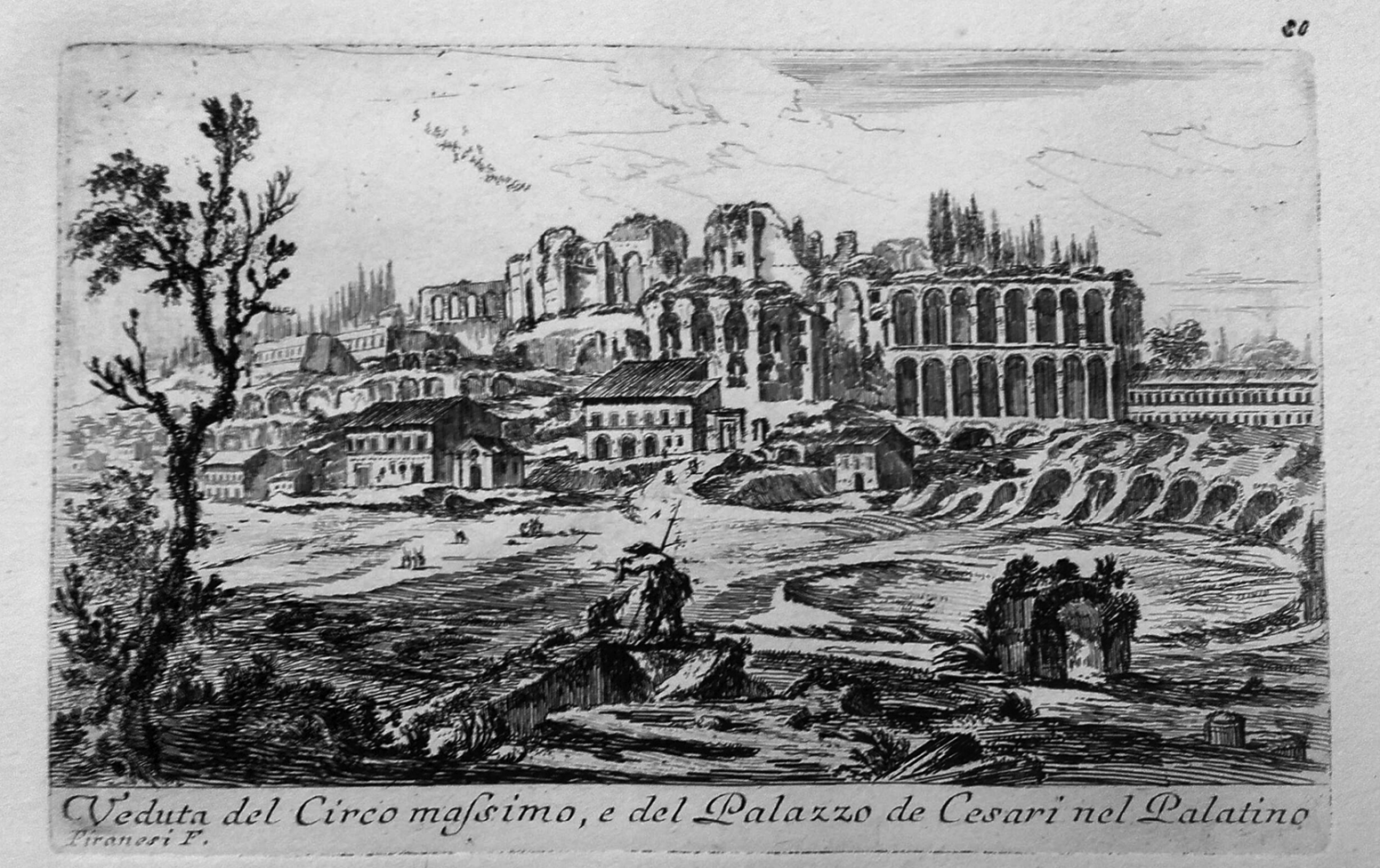

Two circuses were of crucial importance to antiquarians: firstly, because it is the most important and most often cited by ancient authors, was the Circus Maximus – the ‘ur-circus’ not only for Rome but for the Roman world as a whole – and secondly the circus on the via Appia, the Circus of Maxentius, because it was largely above ground, therefore visible, although in ruins. Both of these monuments attracted the attention of Piranesi soon after his arrival in Rome and were included in his collection of small vedute prints.Footnote 11 Fig. 2 is a view of the Circus Maximus, showing the rural aspect of the area under the shadow of the substructures on the Palatine hill. Another print is of the Circus of Maxentius (Fig. 3); it was known from the 16th to 19th centuries as the circus of Caracalla due to a misreading of numismatic evidence (Tomasi Velli, Reference Tomasi Velli1990: 95). Its spina was embellished by an obelisk that lay broken in two pieces above ground until the 17th century and this is now part of Bernini's Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi in Piazza Navona.

Fig. 2. G.B. Piranesi, Veduta del Circo massimo, e del Palazzo de Cesari nel Palatino, pl. 63 from Varie Vedute di Roma Antica, e Moderna (Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

Fig. 3. G.B. Piranesi, Circo di Caracalla, pl. 6 from Varie Vedute di Roma Antica, e Moderna (Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

The theme of circuses was clearly deeply embedded in Piranesi's antiquarian and architectural thinking, thanks to the extant circus on the Appia. A later instance where it is explored is in a beautiful preparatory drawing for an unexecuted view print, Circo di Massenzio e sepolcro di Cecilia Metella. Probably this was originally intended to join two other vedute showing ruins in the area adjacent to the via Appia, the Grotto of Egeria and S. Urbano alla Caffarella (known at the time as the Tempio di Bacco). The view is taken from the hillside to the north of the site and clearly shows the towers of the carceres. Footnote 12

These two exemplar circuses highlight the use of and conflict between two types of evidence used by antiquarians – the authority of the ancient sources (and the ambiguity inherent in their interpretation) and the reality of existing structures; these factors informed the antiquarian discussion and influenced Piranesi.

2. THE CAMPUS MARTIUS PROJECT

Since he settled in Rome in the mid-1740s, Piranesi had been working on the four volumes of the Antichità Romane, the publication of which in May 1756 caused great interest among scholars and erudites across Europe and earned him the accolade of a Fellowship of the Society of Antiquaries of London (Gavuzzo Stewart, Reference Gavuzzo Stewart2014). It has been made clear by Susanna Pasquali (Reference Pasquali and Nevola2016), in her work on the genesis of the Campus Martius plan and volume between the years 1757–62, that Piranesi was intending to extend that four-volume project, adding a large, illustrated plan of the ancient city, specifically the area north of the monumental centre, the Campo Marzio, heavily built up with porticoes, temples, theatres and other public buildings from the period of Augustus onwards. The project eventually became an illustrated volume with the fold-out plan inserted, the accompanying text being a survey of the historical development of the area. Both the plan and its subsequent incarnation as a volume were dedicated to Robert Adam who had been in Rome from 1755–7, studying architectural drawing with teachers connected with the French academy and with Piranesi (Wilton-Ely, Reference Wilton-Ely1978: 21). The Venetian architect intended to capitalize on the fame which his Antichità Romane had brought him in Britain by making the dedication of this new project to a British artist on the grand tour.Footnote 13

The plan of the Campus in the original project was to have been flanked by bird's-eye perspective views of some of the monuments, placed in adjacent areas of the margins, forming a ‘frame’ around the plan. Views of the area near to the Mausoleum of Hadrian and the area inland of the Theatre of Marcellus – the middle and lower sections of the left-hand side of the plan – are the only survivors. These were eventually included in the volume, repurposed as its second frontispiece (Mausoleum of Hadrian view) and the last plate, no. 48 (a sheet of three separate views including the Theatre of Marcellus and the Pantheon).Footnote 14 That first project was abandoned; the Adam letters mention a delay in receiving the desired dedication from Piranesi,Footnote 15 no doubt caused by recasting the project into book form – drafting the text and etching the illustrations – and also by changing the plan in one significant way. The six circuses included by Piranesi within the ancient Campus area were radically altered in their form by the time the project had changed from an illustrated plan to a fold-out in the volume.Footnote 16 In the course of the research for this paper, the two states of the plan have been compared inch by inch and no other differences have been found.Footnote 17

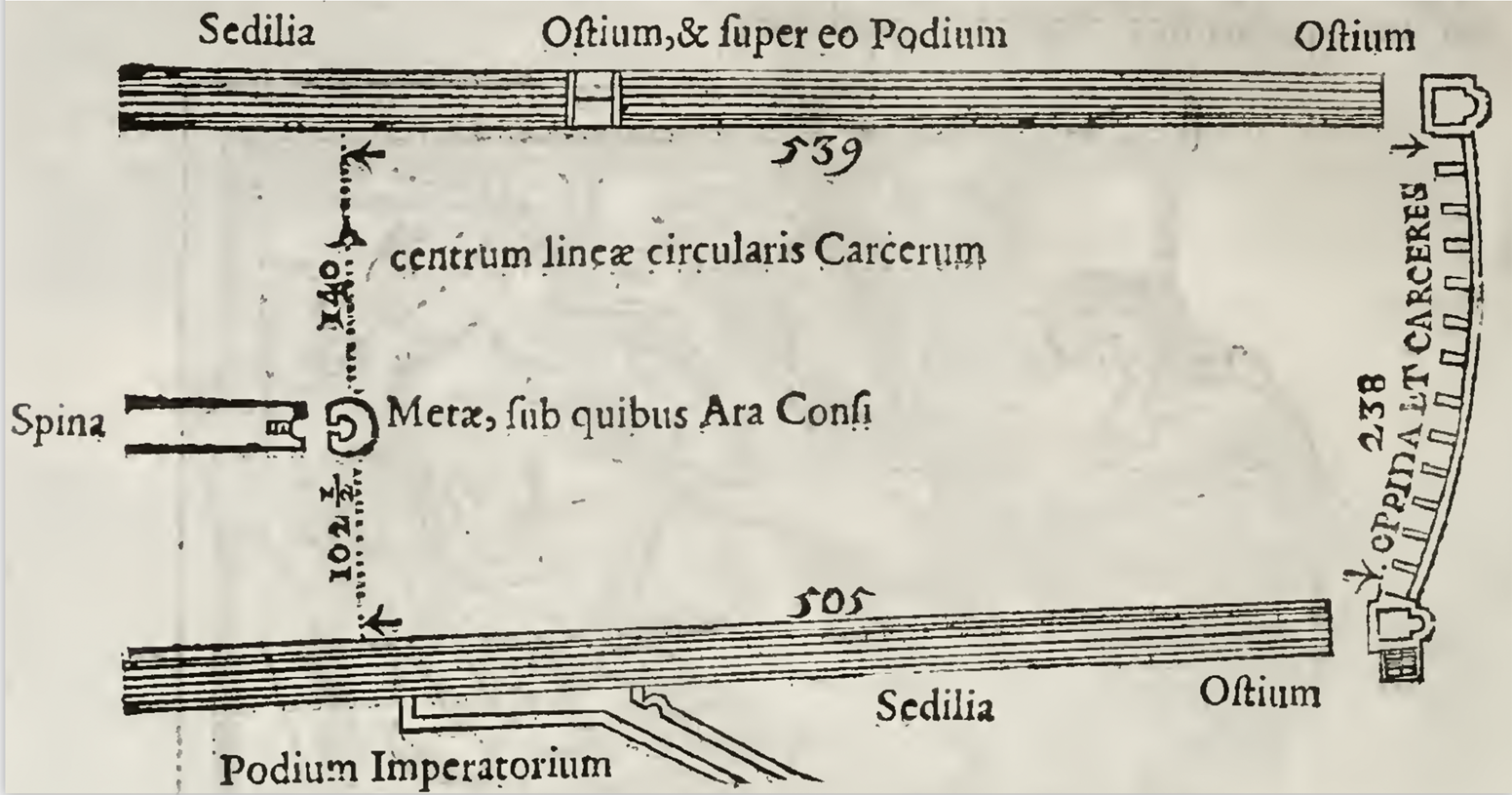

3. CIRCUS MAXIMUS CARCERES ANALYSIS IN THE PIANTA DELL'ANTICO FORO ROMANO

The intimate connection between the Antichità Romane first volume and the idea for a map of the ancient city has been noted by scholars (Wilton-Ely, Reference Wilton-Ely1978: 73); Piranesi had stated this intention, referring to the aqueducts diagram:Footnote 18

Affine però che non mi possa essere obiettato da chicchessia, che io abbia fatta la detta Tavola a capriccio, stimo a proposito dì avvertire, che avendo io, sulla scorta non meno degli antichi Scrittori che degli odierni avanzi delle antiche fabbriche, e de’ frammenti dell'antica Iconografia di Roma riportati in principio del presente Volume, formata una gran Pianta iconografica dell'antica Roma, che fra poco darò alla luce.

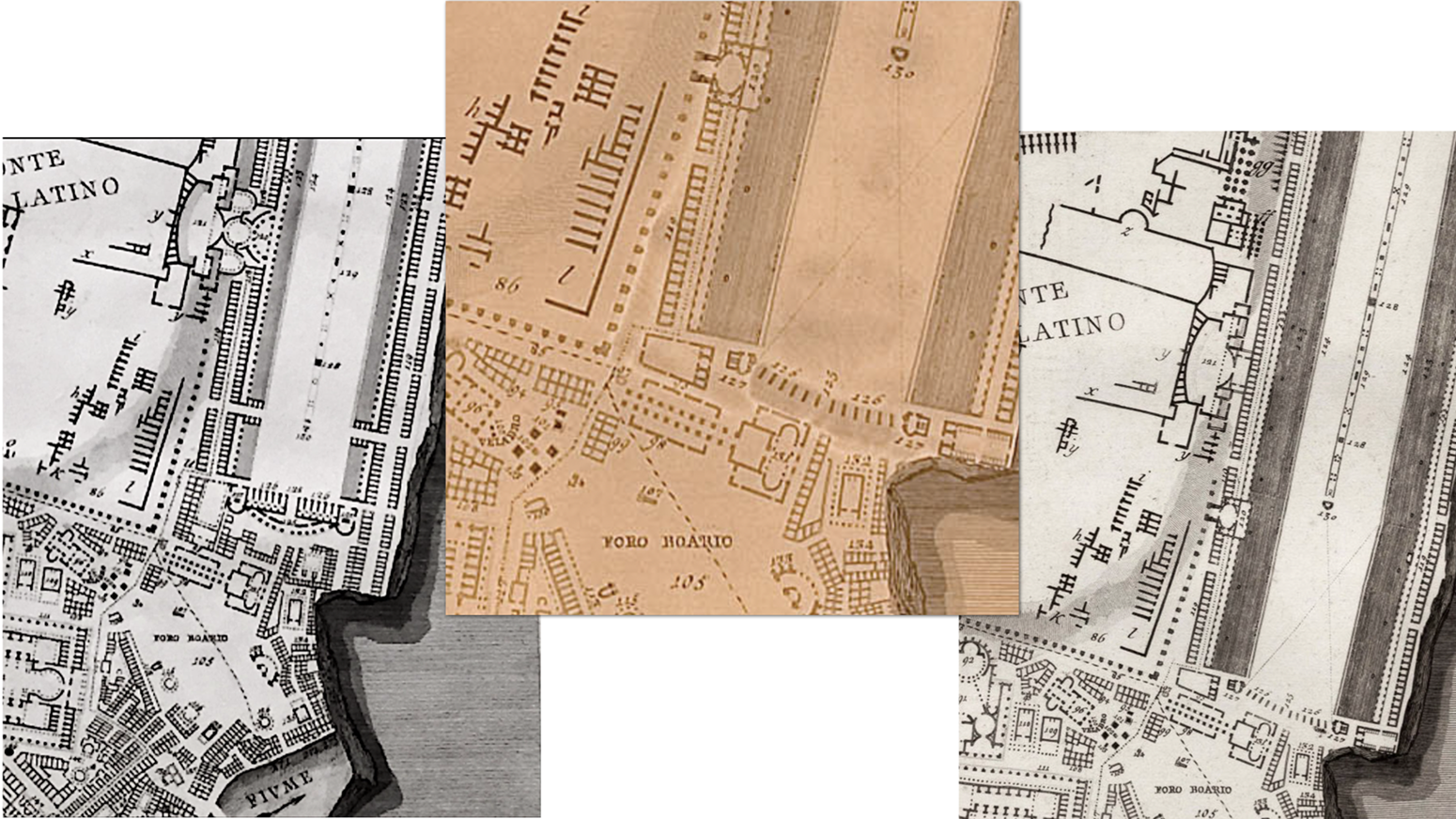

The Pianta dell'antico Foro Romano, pl. XLII of this volume, including the Circus Maximus, employs a graphical language followed directly by the Ichnographia and its genesis is key to understanding the dates and process of the changes to the circuses in the Campus Martius plan. Giovanna Scaloni, in her analysis of the Pianta copper plate and prints (Scaloni, Reference Scaloni and Mariani2014: 157–8), noted abrasion in certain areas, principally around the circus, which explains the existence of two states of the print; she has dated these alterations from between 1756 (the earliest prints of the first state) and 1761 (the date of the copy of the second state presented by Piranesi to the Accademia di S. Luca). The photograph of the copper plate (Fig. 4) shows the abraded areas clearly: the ‘rubbing out’ is noticeable as darker, smudged areas around the carceres and the spina. These changes to the form of the Circus Maximus are the most significant interventions made on this plate and point to the inclusion of a completely different architectural form for this, the most important Roman circus. This change, executed in the years 1757–61, leads to the conclusion that this was the time when equivalent alterations were being made to the circuses in the Ichnographia.

Fig. 4. G.B. Piranesi, Circus Maximus details from Pianta dell'antico foro romano from Antichita Romane vol. I, pl. XLIII (l–r) first state/copper plate, flipped/second state (Creative Commons via Arachne/Istituto Centrale per la Grafica/Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

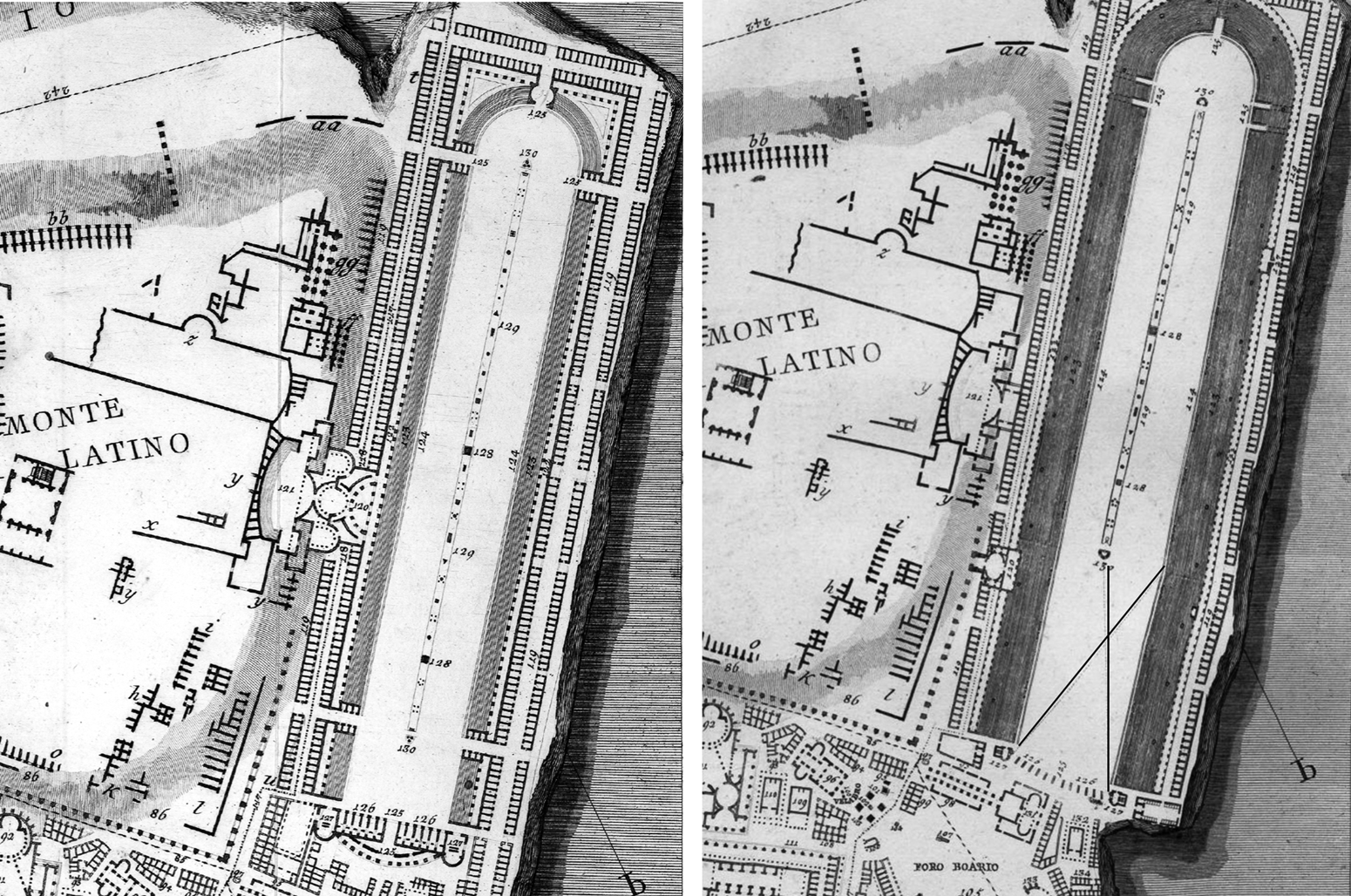

Fig. 5 shows the key areas in the first state of the Circus Maximus: a complex carceres block perpendicular to the long sides of the circus, a long spina and several openings connecting to the neighbouring streets. The second state simplifies these features and closes the openings. It also shows diagrammatic intersecting lines indicating the centre of the circle of which the arc of the carceres is a section. This display of geometrical calculation seems to have been made deliberately to show why it was needed; it can be seen in all the circuses in the second state of the Campus Martius. In the Pianta first state, the separate identity of the towers at the corners of the carceres – the oppida – and other areas are numbered and included in the index.Footnote 19

Fig. 5. G.B. Piranesi, Circus Maximus detail from Pianta dell'antico foro romano from Antichita Romane vol. I, pl. XLIII (l–r) first state/second state (Creative Commons via Arachne/Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

4. ANALYSIS OF THE CIRCUSES IN THE ICHNOGRAPHIAM CAMPUS MARTIUS

Turning to the copper plates of the Ichnographia, it is clear that the circuses here were altered in the same way as was the Circus Maximus in the Pianta. Evidence is present in the areas of abrasion on the plates where the circuses are etched: these darker, rubbed areas are visible notably at the carceres and spina. These interventions indicate where the first design was removed and replaced, explaining the existence of first and second state prints.Footnote 20 This section will present the visual evidence of the changes for each circus in turn, moving across the plan from the left to the right.

At the far left-hand edge of the plan and only partially visible, is what Piranesi calls Circus Caii et Neronis (Fig. 6a), now known as the Circus of Nero; its obelisk is labelled in the first state but erased in the second. In the first state, a temple to Apollo appears on the right-hand flank of the circus, integrated into the structure of the seating areas; in the second state, this connection is severed by a boundary line. The principal changes are that the carceres become an arc, the spina is shortened and the diagrammatic lines between these two elements are added. These changes are repeated in each of the circuses.

Fig. 6a. G.B. Piranesi, Circus Caii et Neronis, details from Ichnographiam Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis (l–r) first state/copper plate, flipped/second state (Library and Archive, British School at Rome/Istituto Centrale per la Grafica/Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

Adjacent to the Mausoleum of Hadrian, Piranesi invented a vast monumental funerary complex, pairing the Circus Hadriani with a symmetrical Circus Domitiae flanking a triangular Clitaeporticus with paths and planting (Fig. 6b). The complex extends from the Pons Aelius Hadrianus inland, forming one of the most striking creations within the plan (Connors, Reference Connors2011: 81). The carceres in the first state have a curious segmental form; they are large, subdivided spaces, apparently unrelated to their function. The twin circuses area of the plan in its first state matches the perspective view in the second frontispiece of the volume (Fig. 7). As mentioned above, Pasquali has shown that this perspective view was part of the original Campus Martius plan project of 1757. The fact that the structures seen in the view and on the plan correspond in the first, but not in the second, state indicates that the ‘plan with views attached’ idea was predicated on the earlier state of the plan.Footnote 21

Fig. 6b. G.B. Piranesi, Circus Domitiae/Circus Hadriani, details from Ichnographiam Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis (l–r) first state/copper plate, flipped/second state (Library and Archive, British School at Rome/Istituto Centrale per la Grafica/Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

Fig. 7. G.B. Piranesi, Circus Domitiae/Circus Hadriani, details from (lhs) bird's-eye view, second frontispiece of Campus Martius Antiquae Urbis and (rhs) Ichnographiam Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis, first state (Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

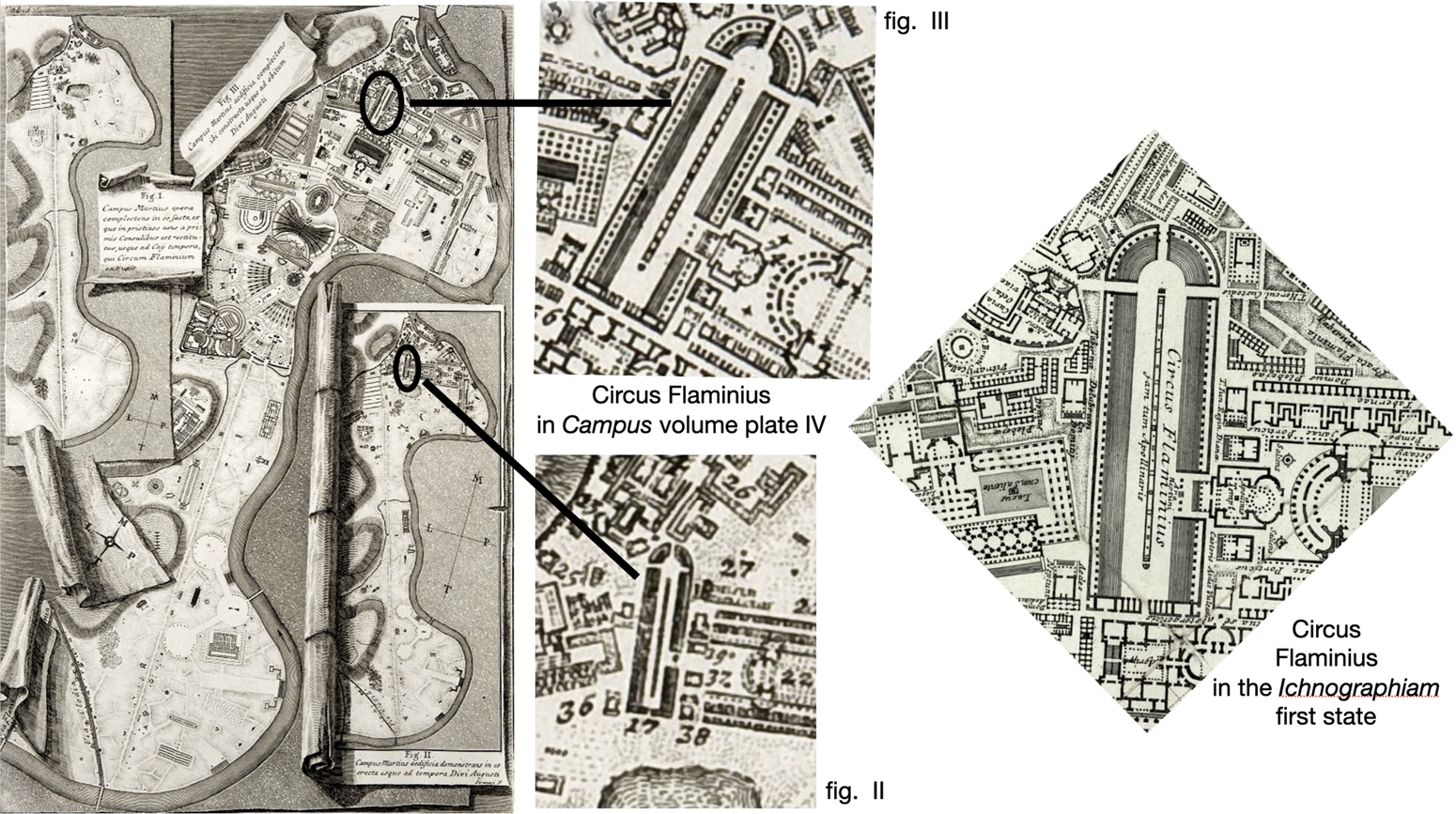

On the opposite bank of the Tiber is the Circus Flaminius (Fig. 8). As at the Circus of Nero, Piranesi integrates a temple of Apollo into the structure in the first state, separated in the second. It is particularly noticeable in the second state that the circus seating area on the chariot drivers’ left-hand side is shorter.Footnote 22 The Circus Flaminius in the first state also supports the ‘first state/first Campus project’ hypothesis; it is clearly shown in this form in two small maps of the Campus Martius, plate IV, figs II and III of the volume (Fig. 9). They depict the Campus in eras prior to that used by Piranesi for the large Ichnographia – a complex, late Empire-based topography (Dixon, Reference Dixon, Smiles and Moser2005: 117–18) chosen because it offered the richest catalogue of monuments for the architect to reconstruct. These small maps show the area at the time of Augustus (pl. IV, fig. II) and at the time of his death (pl. IV, fig. III). Pasquali (Reference Pasquali and Nevola2016: 182, n. 11) has convincingly suggested that these small maps were first intended to flank the plan in the first project, like the bird's-eye views mentioned above, and were to be placed adjacent to the areas at the top of the plan.

Fig. 8. G.B. Piranesi, Circus Flaminius, details from Ichnographiam Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis (l–r) first state/copper plate, flipped/second state (Library and Archive, British School at Rome/Istituto Centrale per la Grafica/Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

Fig. 9. G.B. Piranesi, Circus Flaminius, details from Campus Martius Antiquae Urbis, pl. IV and Ichnographiam Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis, first state (Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

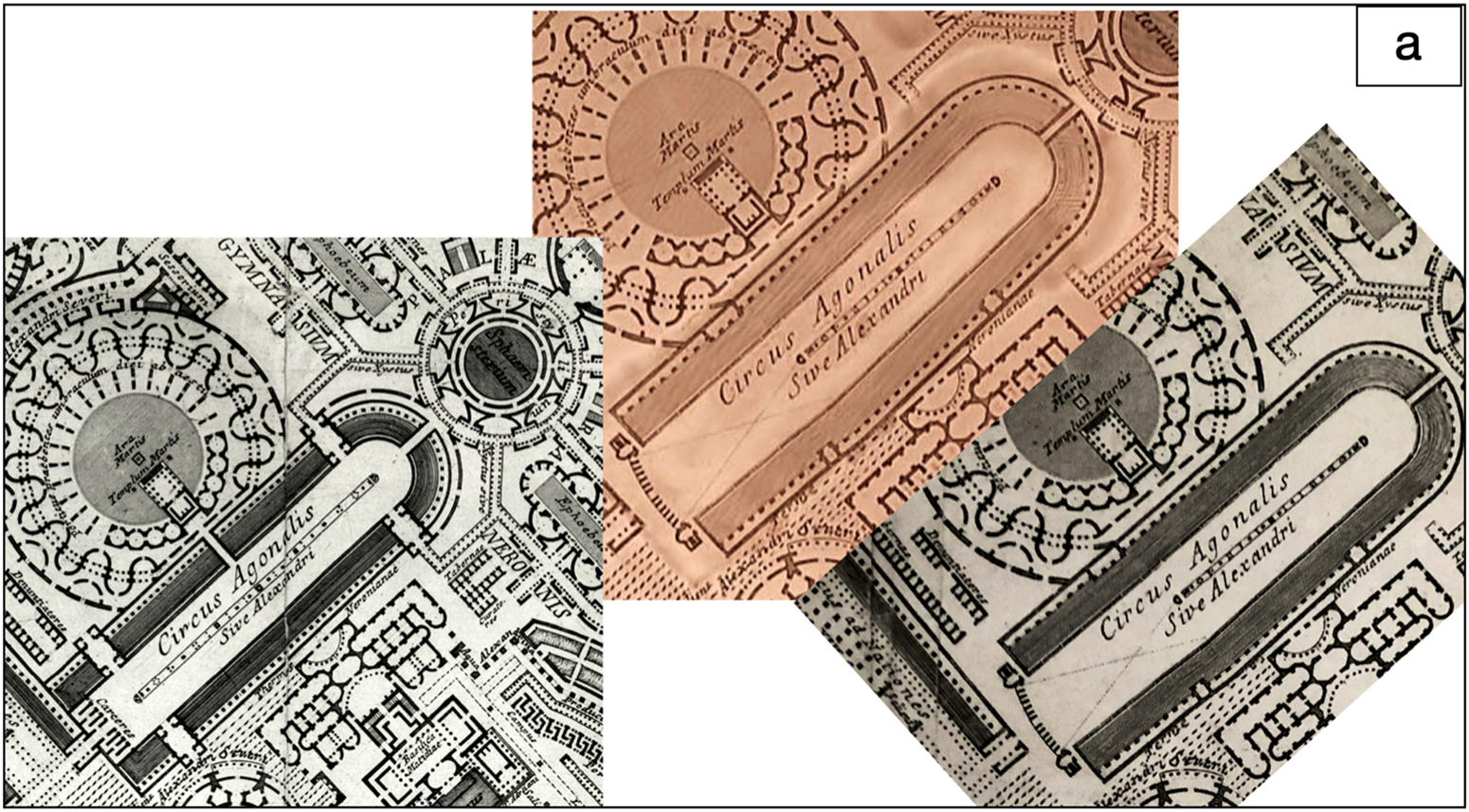

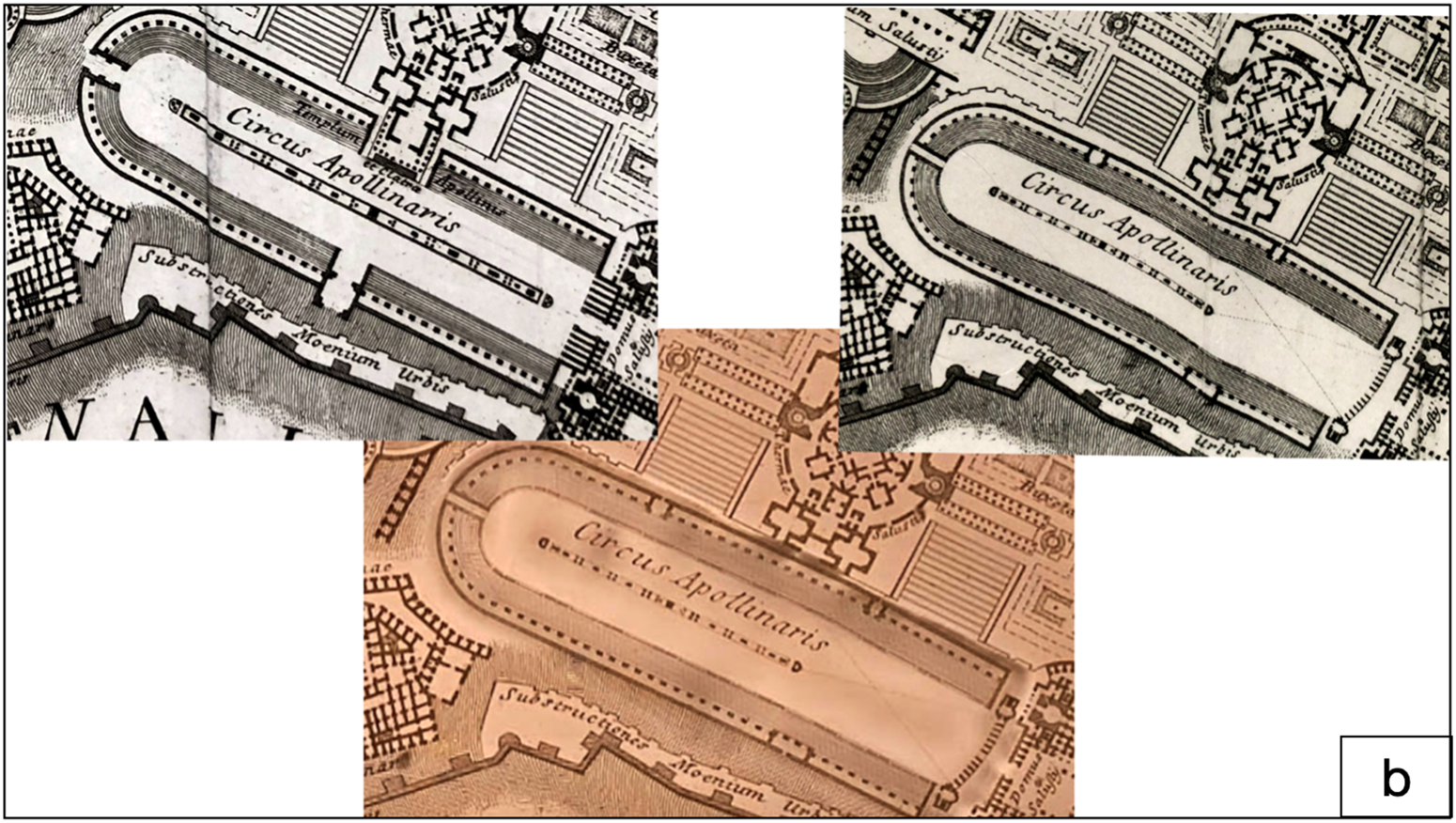

The fifth circus is named as Circus Agonalis (Fig. 10a); it is what we know as Piazza Navona, originally the stadium of Domitian. Next to it Piranesi places a temple of Mars, again integrated with the circus in the first state and he labels the carceres which have a bizarre and impractical maze-like layout. The last circus is the Circus Apollinaris; in the first state, the adjacent baths of Sallust are connected to the structure of the circus (Fig. 10b).

Fig. 10a. G.B. Piranesi, Circus Agonalis, details from Ichnographiam Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis, (l–r) first state/copper plate, flipped/second state (Library and Archive, British School at Rome/Istituto Centrale per la Grafica/Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

Fig. 10b. G.B. Piranesi, Circus Apollinaris, details from Ichnographiam Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis (l–r) first state/copper plate, flipped/second state (Library and Archive, British School at Rome/Istituto Centrale per la Grafica/Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

Piranesi originally designed the carceres to look different in each of the circuses: some have similar forms, but not ever the same (except in the twin circuses, where all details match). In the second state, however, the carceres are identical: they appear to be copied from a model. The other notable difference in the first state is the marked interpenetration of the areas of the circuses with their surrounding urban environment. Piranesi incorporated the circuses into his overall system of viability, using them like the porticoes, gardens and temple areas, available for public access (Hornsby, Reference Hornsby, Bevilacqua and Hornsby2023: 153). But in the second state the circuses are isolated, self-contained structures, the boundaries of which clearly stand out from the rest of the dense network of the plan.

5. THE ANTIQUARIAN CONTEXT OF THE CIRCUSES

In the dedication essay to the Campus Martius volume, Piranesi takes up the challenge of those who accuse him of invention by emphasizing his commitment to examining ancient remains on site.Footnote 23 Supporting evidence is provided by indices, one of which, Catalogo delle opere descritte nella grande icnografia del Campo Marzio/Coll'aggiunta degli autori, e de’ monumenti da’ quali se n’è presa notizia, Footnote 24 lists all the references in the Ichnographia (each building or area is named on the plan in Latin, and they are not numbered), arranged according to type of structure. This index, like the historical narrative in the text of the volume, would have been drawn up by Piranesi's scholarly collaborator.Footnote 25 Under the entry for circuses there is an extensive list of sources for each;Footnote 26 such citations are of course an established part of any scholarly apparatus and their presence sets the Campus volume firmly within the antiquarian tradition. The works which directly influenced Piranesi as designer and artist, however, are referenced only once;Footnote 27 these influences were books and prints published by two of the previous generation of antiquarians, Pirro Ligorio and Onofrio Panvinio. Ligorio's Libro de’ circhi… Footnote 28 had associated prints of two circuses (Ligorio, Reference Ligorio1553b; Reference Ligorio1553c), and his view-map of Rome showed them (Ligorio, Reference Ligorio1561). In Panvinio's lavish folio volume (1600) dedicated to circuses there are several prints.Footnote 29 Their focus – and that of other antiquarians and artists in the 16th and 17th centuries – was naturally the Circus Maximus (cf. Dupérac, Reference Dupérac1575, pls 8,11); thus their proposals for its reconstructed plan and elevation had a significant part to play in influencing the designs made by Piranesi for the Circus Maximus in the Forum plan and for the six circuses in the first state of the Campus Martius plan.

5.1 PIRRO LIGORIO

Pirro Ligorio's book has, in common with much of his vast oeuvre, received considerable scholarly attention.Footnote 30 The Libro de’ circi was the only printed book produced from the mass of manuscript notes made by Ligorio (Tomasi Velli, Reference Tomasi Velli1990: 65; Daly Davis, Reference Daly Davis2008: 5). It is possible that the circuses were chosen by him for publication because of the intense interest of the humanists in this well-documented yet uncodified type of structure; Leon Battista Alberti had probably measured the Circus of Maxentius in the late 1400s or early 1500s (Tomasi Velli, Reference Tomasi Velli1990: 115). Twenty-four pages of the Ligorio volume concern the circuses; he discusses the important ceremonies – both religious and political – which led to the celebration of games and the competitions held for the entertainment of the ruling elites and the public, his reference point being the Circus Maximus as the earliest and most significant site. The rest of the book is the Paradosse in which he sets out to confute the erroneous opinions of previous scholars on the monuments of Rome. Ligorio's polemical, combative stance vis-à-vis other antiquarians here is very like that of Piranesi's nearly 200 years later in his tracts such as the Osservazioni and the Parere (Piranesi, Reference Piranesi1765; see Wilton-Ely, Reference Wilton-Ely1972). There are other aspects which the two men have in common: neither was particularly gifted in Latin (nor in Greek) (Tomasi Velli, Reference Tomasi Velli1990: 86) and both were artists given to fantasy in architectural reconstruction (Connors, Reference Connors2011: 57–60).

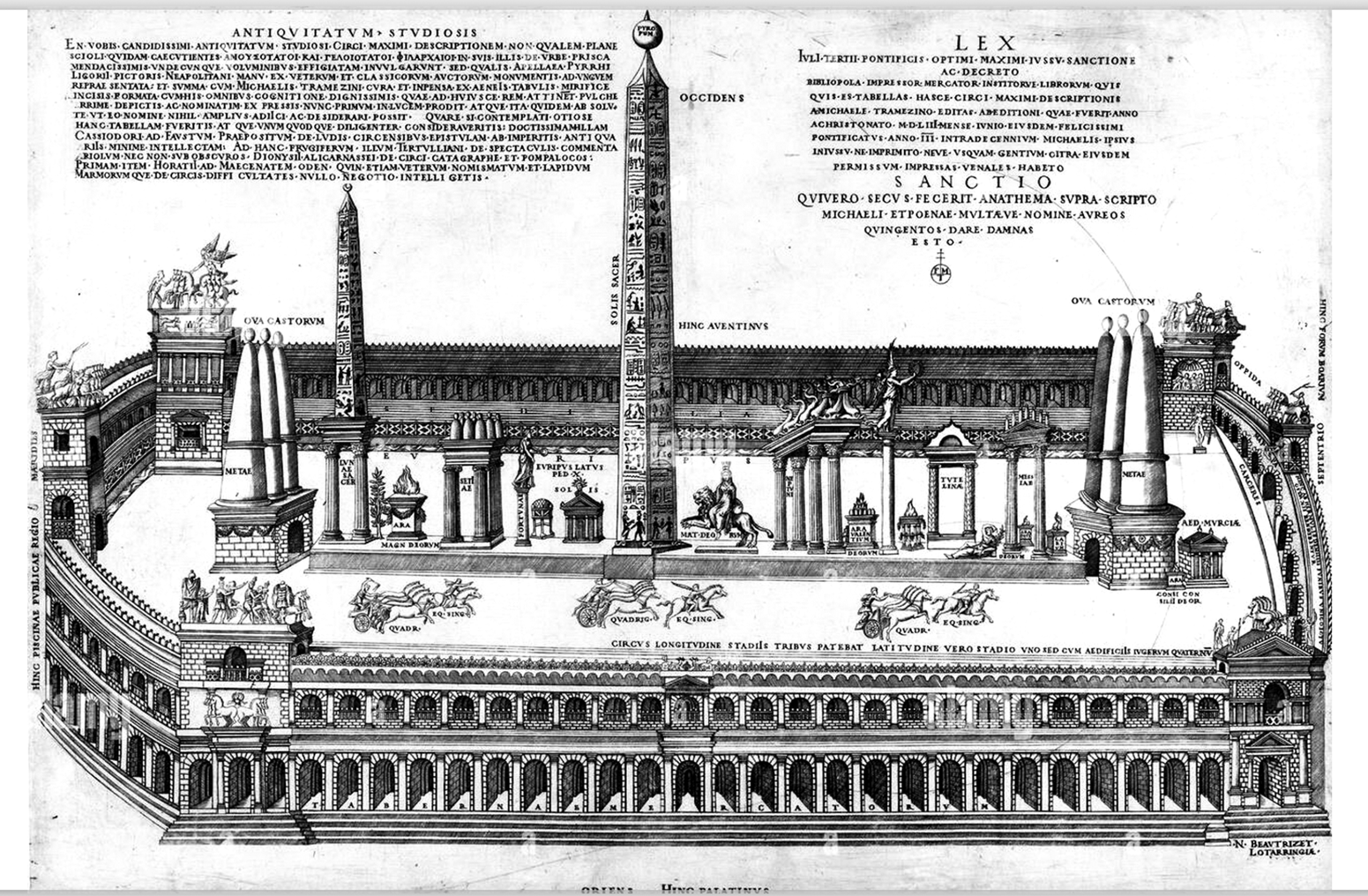

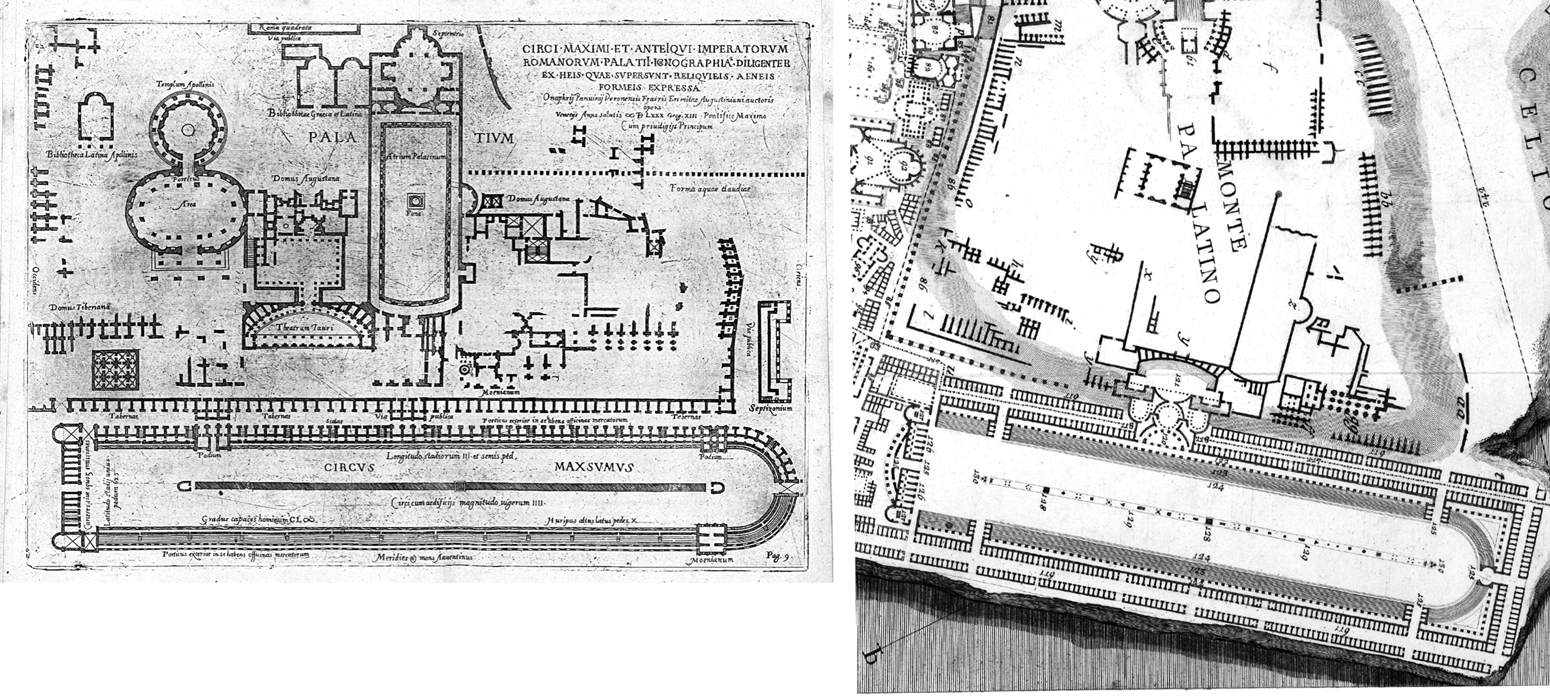

Ligorio lists nine circuses in Rome (1553a: 1r):Footnote 31 ‘Erano adunque in Roma nove Circi, da Greci Hippodrome, de’ quali il più nobile, & il più bello & prima di tutti gli altri instituito, era il Massimo.’ At the same time as the treatise was published, the print entitled Antiquitatum Studiosis… (Fig. 11) appeared; it is a reconstruction of the Circus Maximus, viewed from the Palatine towards the Aventine hill. The shallow arc of the carceres on the right-hand side is visible, with the corner towers labelled oppida. Ligorio cites Varro quoting Naevius for this name (Ligorio, Reference Ligorio1553a: 7v.). The complex oppida constructions which Piranesi designed as the starting gates in the first state of the Campus plan have their origins in the Ligorio image. The long caption is his authorship; he includes some phrases in Greek that have been revealed to be obscure or incorrect (Tomasi Velli, Reference Tomasi Velli1990: 83). He labels many of the parts and includes items that are mentioned in the ancient sources, such as a statue of Hermes on the extreme top right of the circus, adjacent to the carceres; different ideas had circulated about the herms placed by the starting gate and what their role might have been.Footnote 32

Fig. 11. Pirro Ligorio/Nicolas Beatrizet, Antiquitatum Studiosis…, Reconstruction of the Circus Maximus (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Creative Commons via Google Arts and Culture).

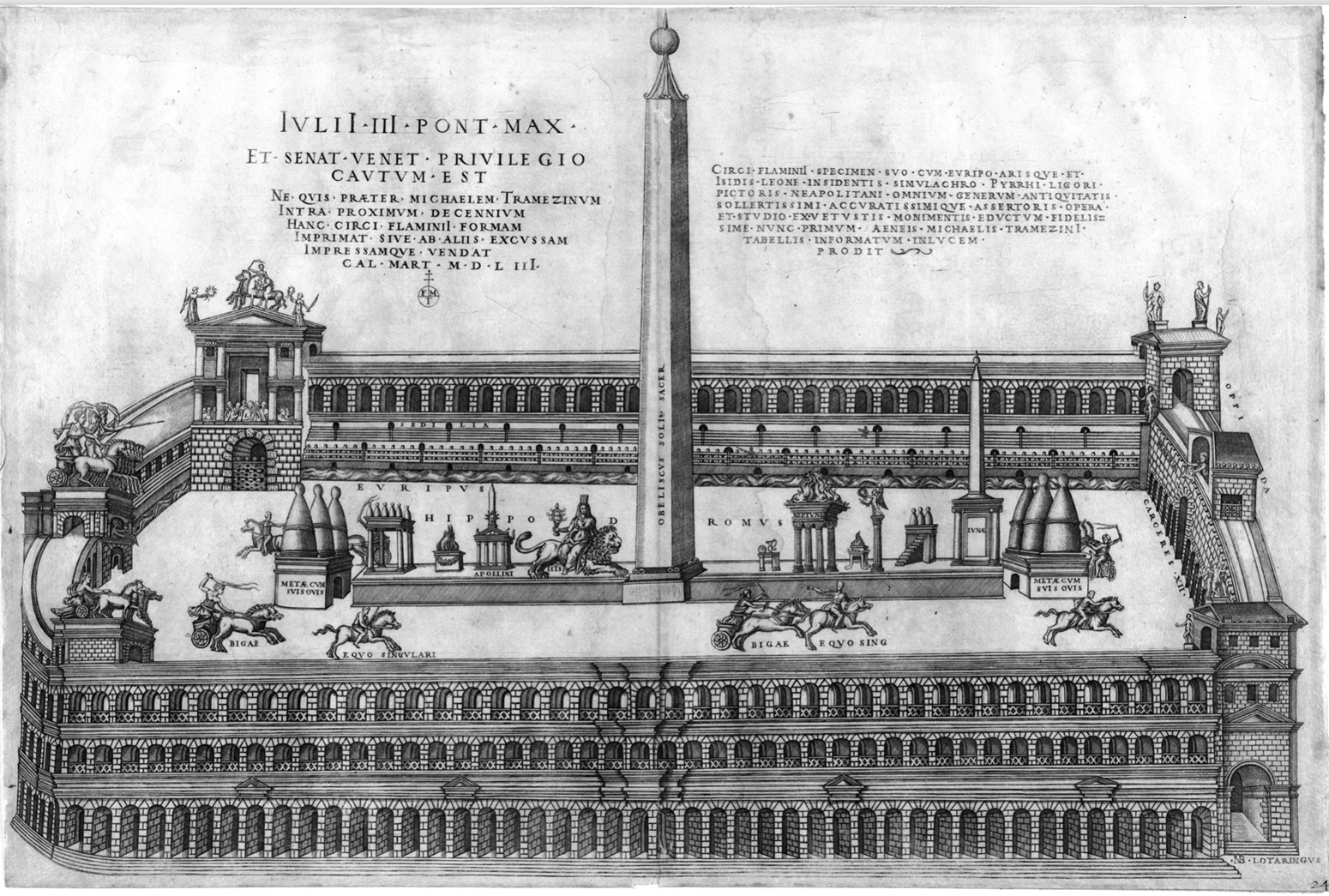

The second of the two prints that are mentioned in the text of the Libro de’ circi is a reconstruction of the Circus Flaminius (Fig. 12). It has been proven that this circus almost certainly did not have fixed stands for spectators nor a spina with the accoutrements like those of the Circus Maximus, as shown in this print (Wiseman, Reference Wiseman1974). The Flaminius comes second in his list of nine circuses; it is possible that Ligorio originally planned to create reconstructions of all of them.

Fig. 12. Pirro Ligorio/Nicolas Beatrizet, Circi Flaminii Specimen…, Reconstruction of the Circus Flaminius (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Creative Commons via Google Arts and Culture).

The circuses feature in the famous bird's-eye view of the city of 1561, in which Ligorio gives free rein to his reconstructive creativity.Footnote 33 This plan was crucial to Piranesi's visual vocabulary of the Campus Martius and its architecture; it also influenced his choices of the location of some ancient sites, although Piranesi's topographical speculations vary from Ligorio's in many cases (Connors, Reference Connors2011: 59; see Tables 1–2). Of the nine circuses featured in the Libro de’ circi only the Circus of Maxentius is not included in the map as it is too far outside the walls of the city. It is significant that Ligorio had material evidence for the form of the Circus Maximus, derived from a depiction on an ancient coin. He wrote (Ligorio, Reference Ligorio1553a: 9v.):

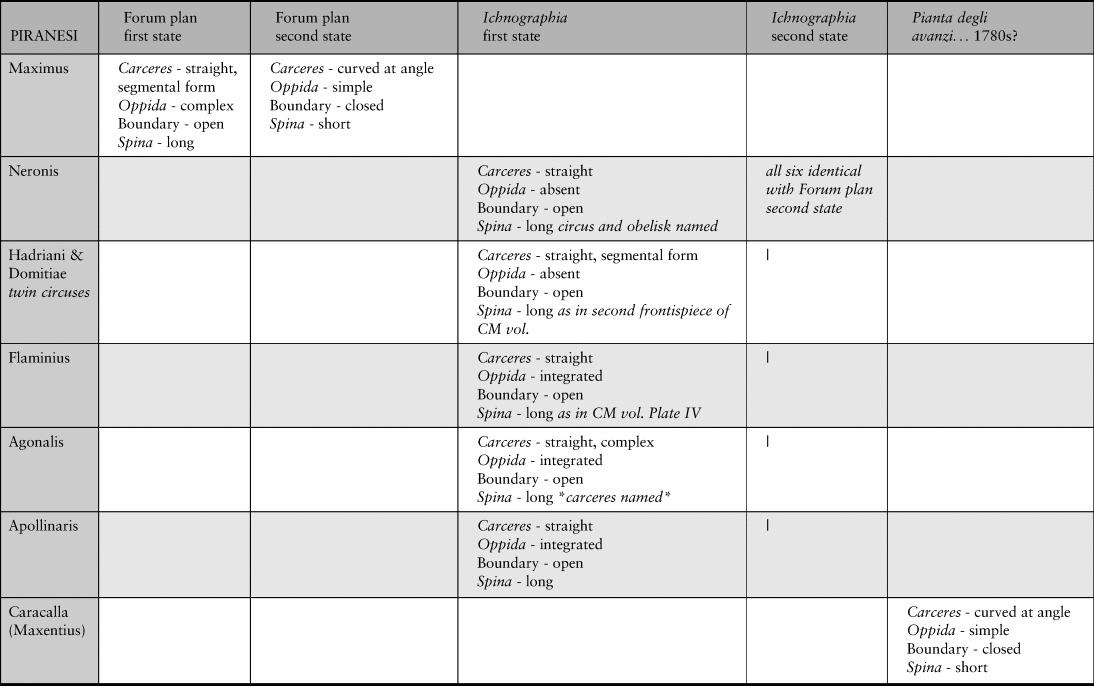

Table 1 Circuses in Piranesi

Table 2 Circuses prior to Piranesi

Penso bene, che la vera [forma del circo] possa vedere nelle medaglie di Traiano imperatore, che fu uno di quelli che lo restaurò, come si legge negli epitomi di Dione.

There is a direct correspondence between the details of the design of the Circus Maximus as shown on coins (Fig. 13) and Ligorio's own reconstruction.

Fig. 13. Sestertius of Trajan, circa AD 103–11, reverse showing the Circus Maximus (Yale University Art Gallery, Creative Commons).

5.2 ONOFRIO PANVINIO

Panvinio's De Ludis Circensibus was published in 1600, although it had been prepared earlier, only ten years or so after Ligorio's book and print were in the public domain (Tomasi Velli, Reference Tomasi Velli1990: 138); his debt to Ligorio is considerable and obvious and yet goes unacknowledged (Tomasi Velli, Reference Tomasi Velli1990: 148–9 and 158). This type of omission is not unusual amongst the antiquarians of the early modern period; Piranesi also often named those whom he wished to criticize and kept silent about those to whom he was indebted. Panvinio puts all nine Ligorian circuses in his map of Rome, which is included at the beginning of the book, extending to the Circus of Maxentius; all are identical in form.Footnote 34 The plan is oriented upside down as compared with Ligorio's and includes only the main ancient monuments, but it has the same name as his predecessor's map; this adoption of the work of Ligorio and rebranding of it under his own name, with a few but not many variations, occurs throughout this publication.

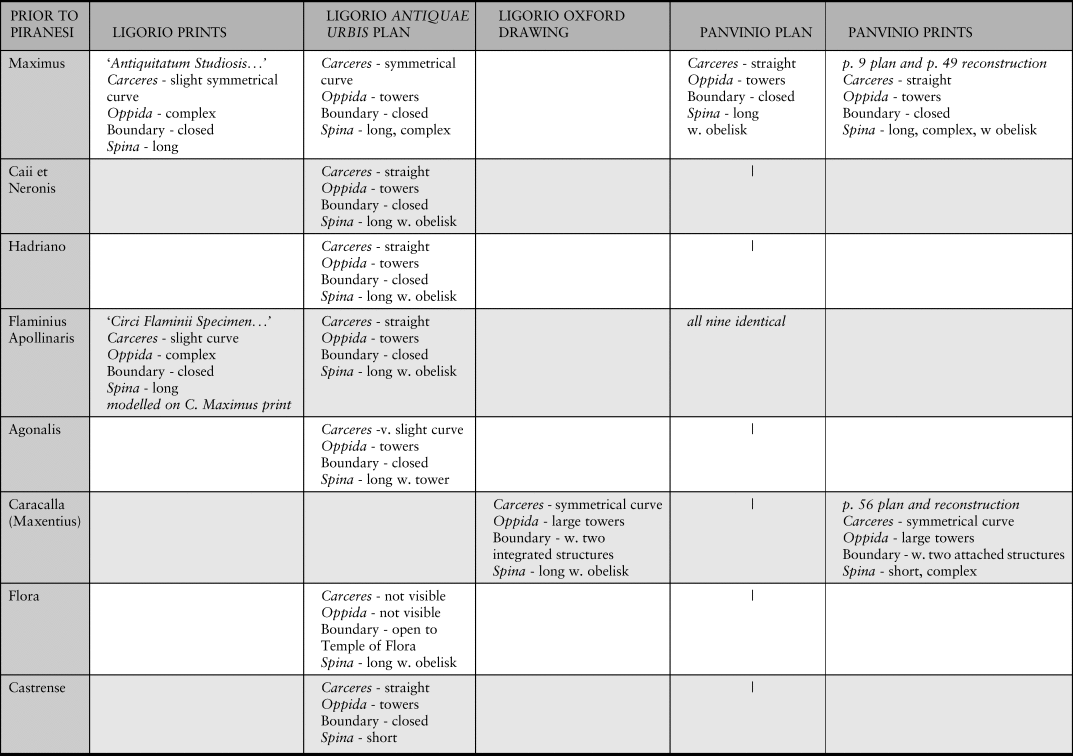

Focusing on the Circus Maximus, it is instructive to compare Panvinio's solution, dated c. 1560, with Piranesi's almost exactly 200 years later (Fig. 14). The former's inclusion of the structures visible on the Palatine is evidence of the state of scholarship at the period, though how reliable it was is unclear (Tomasi Velli, Reference Tomasi Velli1990: 130, n. 216). Piranesi benefited from the recent archaeology of Francesco Bianchini; he shows the basilica hall that Bianchini had discovered (Reference Bianchini1738).Footnote 35 The permeability of the circus in Piranesi's first state and the integration of the palace on the hill with the circus itself are features original to Piranesi and are not present in either Ligorio or in Panvinio.

Fig. 14. (l–r) Onofrio Panvinio, De Ludis Circensibus…, p. 9. Plan of the Palatine and Circus Maximus/G.B. Piranesi, Circus Maximus detail from Pianta dell'antico foro romano from Antichita Romane vol. I, pl. XLIII (oriented for comparison) (Public domain via archive.org/Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

Panvinio's reconstructed view of the circus (Fig. 15) made a notable change from his predecessor regarding the carceres, which he labelled on both the plan and the view; they are set in a rectangular not a curved structure.Footnote 36 The print also reveals an egregious example of Panvinio taking across elements from the Neapolitan scholar's work without re-checking sources, underlining the interdependence of scholars on each other's interpretations. It concerns the presence on the spina of a little tree in a pot (the fifth object from the left-hand meta), labelled Surculus. This feature is included by Ligorio, based on a misreading by him of a text by Tertullian in Spectacles where he refers to a tree metaphorically present in the Circus (Tomasi Velli, Reference Tomasi Velli1990: 157). Mistakes and all, Panvinio's treatise was a reworking of Ligorio's book and a re-presentation of the ancient sources; with its publication he established the scholarship on ancient circuses for the next 200 years.

Fig. 15. Onofrio Panvinio, De Ludis Circensibus…, pl. M, p. 49. Reconstruction of the Palatine and Circus Maximus (Public domain via archive.org).

6. THE CIRCUS OF MAXENTIUS

The circus then known as the Circo di Caracalla naturally interested Ligorio and Panvinio. Ligorio's drawing (not illustrated here) is a curious mixture of analysis in the plan of the seating rows and walls, with a perspective view of what the spina could have looked like with the obelisk at the centre.Footnote 37 It is likely that this drawing was made around the same time as his Circus Maximus print (seen in Fig. 11), since the manner of the depiction of the arc of the carceres is similar in both. Despite the fact that the ruins were above ground, it is by no means clear that Ligorio was on site to examine them; had he done so, he might have been expected to notice the off-centre position of the carceres.

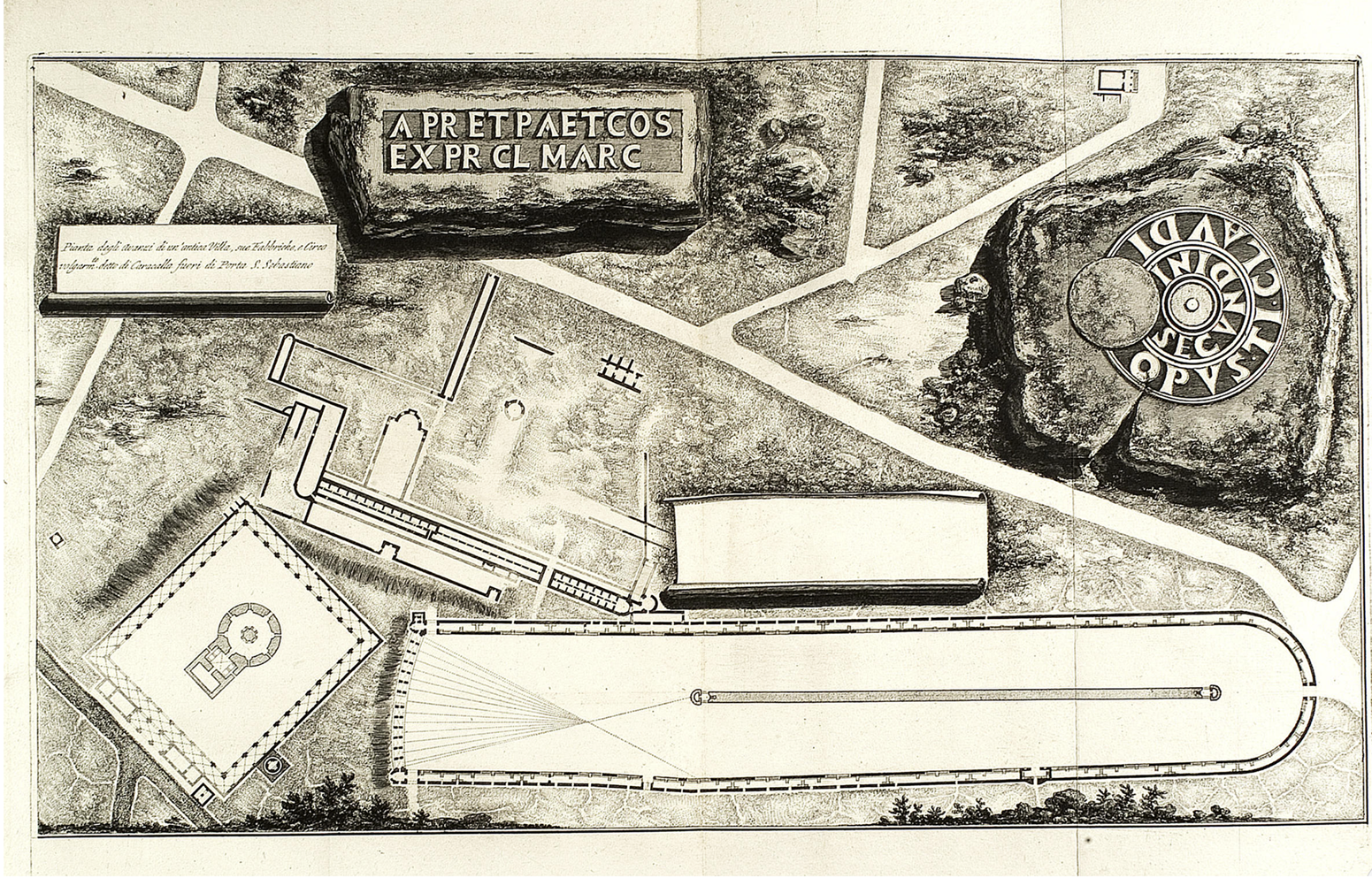

Possibly Ligorio used Dupérac's print (Fig. 16) as a visual source; it is an aerial view looking towards Rome, showing the ruinous state of the monument, similar to the Vestigi del Circo Massimo from the same collection (Dupérac, Reference Dupérac1575: pl. 40). This image certainly influenced Panvinio, since in De Ludis (Reference Panvinio1600: pl. Q pag. 56) he includes a very similar view, removing some of Dupérac's artistic touches, such as the animals in the fields, and adding labelling to indicate the identity of the various ruined structures.

Fig. 16. Etienne Dupérac, Vestigij del circo di Caracalla from I vestigi dell'antichità di Roma (Library and Archive, British School at Rome).

By contrast, Panvinio's architectural reconstruction in plan and in perspective (Fig. 17) includes a considerable amount of speculative antique detail, more than is present in the ‘Oxford’ drawing by Ligorio, although the carceres shown in plan are very similar. There is evidence here that Panvinio had access to other circus-related drawings by Ligorio, particularly one showing the corridor structure which attached the palace to the circus; this can be seen at the lower edge of his plan, at the bottom of the print, jutting into the inscription.Footnote 38

Fig. 17. Onofrio Panvinio, De Ludis Circensibus…, Circus Castrensis Lateritius Caracalla Vulgo Appellatus, pl. P, p. 56. Reconstruction and plan of Circus of Caracalla (Public domain via archive.org).

7. FABRETTI AND BEYOND

Despite the noted antiquarian credentials of Ligorio and Panvinio and their influential prints and drawings, it was another scholar, from a slightly later generation, who undertook the challenge of the necessary encounter with reality; only personal experience and precise recording of the physical evidence could counter their inaccurate interpretations of the ancient sources and conjectural visual presentations.Footnote 39 Raphaele or Raffaello Fabretti is the unsung hero of the story of ‘la vera forma’ of ancient circuses. Fabretti, born in Urbino c. 1620, was a cleric, lawyer and diplomat who had served in Spain and who developed a great interest in archaeology in his later years, especially epigraphy. His work is less familiar now than that of other antiquarians, yet he was a noted scholar in his time; he died in Rome in 1700 (Evans, Reference Evans2002: 4–9). He was known in his day for his book on aqueducts, the De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae dissertationes tres, three short examinations of the aqueducts around Rome undertaken from 1677–9, with diagrams and maps included. Given the evidence of his detailed measuring of the remains of the aqueducts, it is clear that he came to this site on the Appia with his measuring stick and notebook; in a topographical map included at the beginning of the third dissertation,Footnote 40 the Circus of Maxentius is shown (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. Raffaello Fabretti, De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae dissertationes tres, p. 4. Detail of map of the Campagna showing the area near S. Sebastiano on the via Appia (Public domain via Google Books).

The publication by Fabretti that is relevant to this discussion is De columna Trajani syntagma dating from 1683. The title page indicates the intended focus of his study: Trajan's column, specifically in reference to prints published by Giovanni Bellori and Pietro Santi Bartoli when scaffolding was put up around the column between 1665–70 at the request of Louis XIV who wanted casts of the reliefs (Panciera, Reference Panciera and Panciera2006: 1694). Fabretti's pamphlet, coming just over ten years after Bartoli, is a rebuttal of certain details presented by him and is a historical account of the Dacian wars, illustrated with images and small plans set into the text. His digression on the subject of circuses appears at the beginning of chapter six, Observanda circa veterum ritus & superstitionem (Fabretti, Reference Fabretti1683: 141–78, esp. 141–51), the context being that of images of processions with animals, based on reliefs, coins and gems. He goes into the sources and current antiquarian opinions on the Circus Maximus, including an image showing a panel with a quadriga from Trajan's column. Then, with the illustration on page 148 he turns to the evidence provided by the Circus of Maxentius (Fig. 19), providing a diagram of the carceres, spina and the alba linea. This was either the finishing line or the line at which the chariots were allowed to break out of their starting positions to find an advantage on the inside track (Humphrey, Reference Humphrey1986: 20–2). This is the key step-change from anything previously proposed by Ligorio or Panvinio. In the accompanying text, Fabretti criticizes Panvinio for lack of consistency and for creating confusion. Emphasizing his point regarding the carceres, he adds the plain statement of fact (Fabretti, Reference Fabretti1683: 148): ‘non in recta linea sed in orbem collocatis’.Footnote 41 The diagram shows that measurements were taken by Fabretti of the track on either side of the spina; it seems that he even undertook some rudimentary excavation, clearing earth from around the end of the spina to clarify the form of the meta. Footnote 42 His statement indicates that the carceres arc was in reality not centred on the spina itself, but to a point to the right of it (this makes sense in order to equalize the distance to run for the chariot from the extreme left carcer with that on the extreme right). The diagram also shows the shorter seating wing on the competitors’ left-hand side and the much greater distance between the end of the spina and the carceres than appears in either Ligorio or Panvinio.Footnote 43 Emphasizing the point about the carceres, Fabretti cites Ovid in his Amores (3.2.65–6), on attending a race at the Circus Maximus:Footnote 44

Maxima iam vacuo praetor spectacula circo

quadriiugos aequo carcere misit equos

Fig. 19. Raffaello Fabretti, De columna Trajani syntagma, p. 148, diagram of the carceres of the circus of Caracalla (Public domain via archive.org).

It seems unlikely that this phrase of Ovid could, by itself, be enough to indicate the curve or the angle of the curve that is visible in Fabretti's diagramFootnote 45 – the exact curve that appears in the second state of the Piranesian circuses. Yet Ovid can act as support for the empirical evidence produced by Fabretti: that for the race to be fair, the curve must have been set at an angle. Neither Ligorio nor Panvinio specifically quoted the Ovid text: Ligorio had been inconsistent with it and Panvinio had ignored it; only Fabretti had it right. In his essay he adopted a ‘belt and braces/textual sources and physical evidence’ approach in his presentation of the form of the carceres, yet it was principally his first-hand empirical work of excavation and measurement undertaken on site that enabled him to draft his diagram.

Nearly 100 years later, when Piranesi first drew the circuses for his plan of the Forum and the Ichnographia, it appears that either he did not know about these relevant pages of Fabretti – perhaps because the circus evidence is buried within a Latin text on a completely different antiquarian subject – or perhaps he knew of the text, but deliberately ignored it.Footnote 46 Possibly his collaborator, criticizing the ‘complex’ circuses and carceres in the original Forum map and Ichnographia, raised this point: that not only was the evidence for the carceres of the Circus of Maxentius there for all to see, but it had been published by Fabretti many decades previously. The closeness of Fabretti's diagram to Piranesi's second state carceres shows that it must have been his model.

Fifteen years after the Campus Martius project, years in which Piranesi had published a series of volumes focusing on the primacy of Roman architectural and decorative genius, he was still concerned with the Circus of Maxentius. Diary entries from 1774 and 1775 by Sir Roger Newdigate, noted English grand tourist and collector – and the purchaser of two important candelabra made by Piranesi, the Newdigate candelabra – reveal that by 1775 Piranesi had made a plan of the Circus:Footnote 47

[1775]

8th March Sre Piranese bt [brought?] his plan of the Circus of Caracalla & explaind it

10th March To Sre Piranesi who lent his plan of Circus of Caracalla went there, saw the Temple & Portico and examined the Circus till past 4

Piranesi died three years later in 1778 and in the 1784 edition of the first volume of the Antichità Romane, published by his son Francesco, a print of the Circus was included at the end, following the Pianta dell'antico Foro. Could this print (Fig. 20) by Francesco, presenting the structure of the circus much as Fabretti had drawn it, be based on the ‘plan’ that Newdigate borrowed from Piranesi and took on site with him in 1775?Footnote 48

Fig. 20. Francesco Piranesi/G.B. Piranesi?, Pianta degli avanzi … circo di Caracalla, unnumbered last plate of Antichità Romane vol. I, 1784 Rome edition (Public domain via Heidelberg University Library).

Another account of Piranesi's late-stage interest comes in a somewhat ungenerous biography first published in 1779 by his fellow antiquarian, Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi, just after the architect's death (Bianconi, Reference Bianconi1802). The citation that follows here refers to Piranesi going to the Circus of Maxentius ‘ultimamente’ – that is, recently, in his last years – to undertake research and that ‘others’ (Bianconi is in fact referring to himself) were making the same investigations. Bianconi also emphasizes the importance of this Circus as the only physical evidence of the form (Bianconi, Reference Bianconi1802: 137–8):

Stava pure facendo ultimamente alcune ricerche sulle rovine del Circo detto di Caracalla, che si vedono a due miglia fuori della porta Capena, rovine tanto più degne del pubblico, quanto che questo circo è il solo a nostra notizia in tutto il mondo, di cui restino vestigia sufficienti per darci idea dell'architettura circense più composta di quello che si è sinora creduto. Strana cosa, che de’ circhi non ci faccia menzione di Vitruvio. Avendo qualche amatore dell'arti antiche e nostro conoscente fatto egli pure indefesse ricerche sopra queste rovine, saremmo ben contenti di rendere qui giustizia agli studi del Piranesi, se di questi non ci fosse stato un mistero.

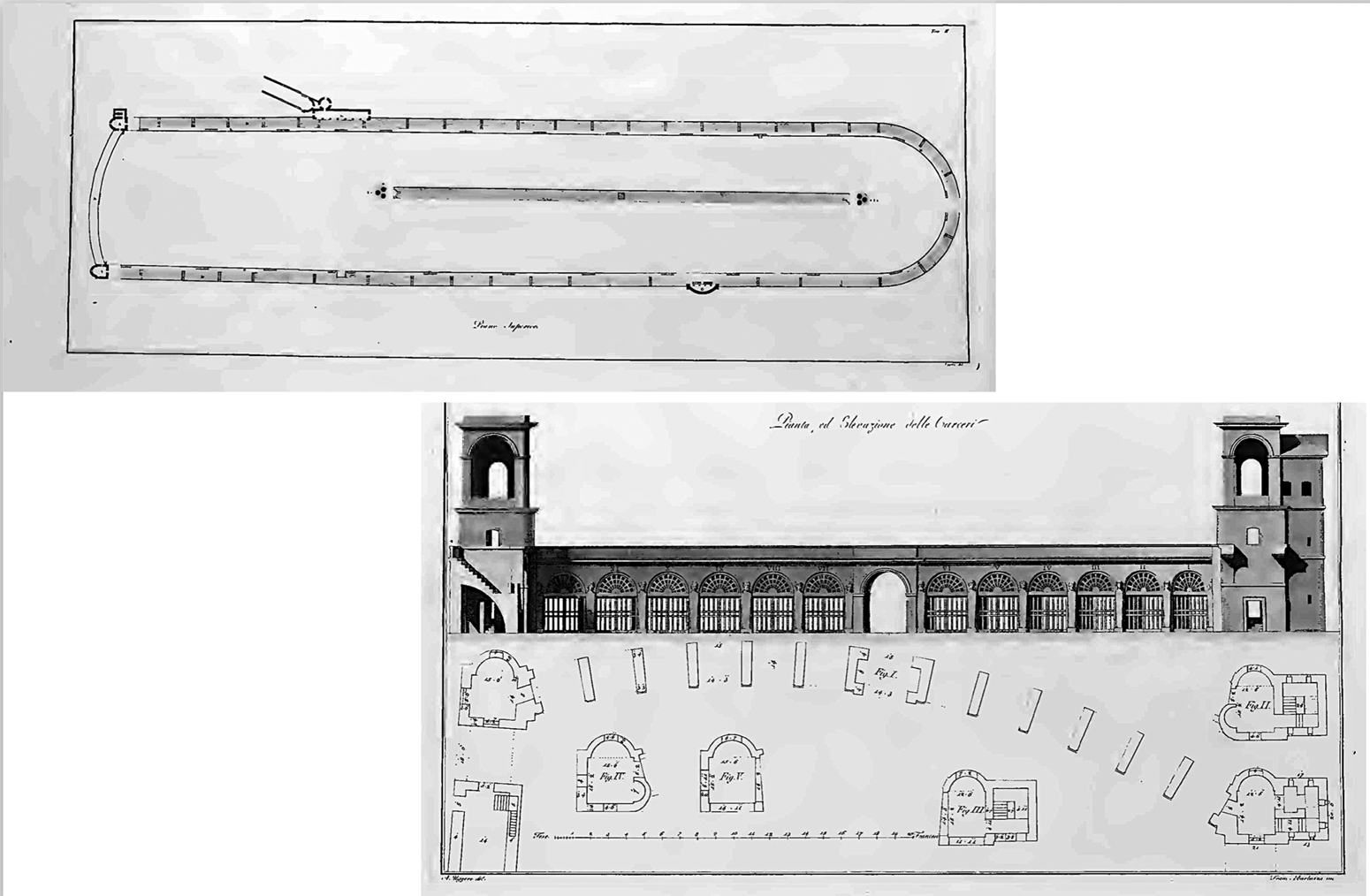

Bianconi's own investigations on that site were to bear fruit in a volume published with a preface by Carlo Fea in 1789 and with plans and elevations, largely drafted by Angelo Uggeri (Fig. 21). The publication of this book codifies what was then known of that Circus – and circuses in general – more than 100 years after the work of Fabretti. He is credited as the only antiquarian who was correct, as opposed to Panvinio, while Piranesi is castigated (Bianconi, Reference Bianconi1789: X). Whereas Bianconi, in his Elogio, had merely described Piranesi's studies of the Circus as ‘un mistero’, Fea, in his preface, ignoring conventional politeness, described the Piranesian solution as (Bianconi, Reference Bianconi1789: X): ‘piena di sogni, e di enormi spropositi, frutto o di malizia, o di crassa ignoranza, o di storditaggine’. By the 1790s, the forms of the spina and the carceres and the geometrical relationship between the two in ancient circuses had been firmly established, based on the evidence provided by the Circus of Maxentius (Colaceci and Cianci, Reference Colaceci and Cianci2017).

Fig. 21. Angelo Uggeri in Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi, Descrizione dei Circhi particolarmente di quello di Caracalla e dei Giuocchi in essi celebrati: (top) p. xci, pl. II, Piano Superiore and (bottom) p. xciii, pl. VI, Pianta ed Elevazione delle Carceri (Public domain via archive.org).

The analysis undertaken in this essay reveals that Piranesi accepted the need to erase his initial designs – perhaps it was these which Fea criticized so pungently – in order to adopt the correct, albeit less visually compelling, solution. In respect of the form and structure of the ancient circus, if not in other areas, we see Piranesi the creative artist bowing to the inevitability of archaeological evidence – surely a sign of the times.

8. POSTSCRIPT: A COINCIDENCE – OR NOT?

At the end of the 1750s and early 1760s when Piranesi was altering the copper plates of the Ichnographia to produce a second state, his mind was much concerned with the theme of carceres, but not only those constructed for chariot-racing. Probably the most famous etchings of all of his production are the sixteen ‘fantasy prisons’, the Carceri d'Invenzione, Footnote 49 enigmatic architectural creations depicting vast interlocking spaces, soaring stone staircases, looming parapets and terraces, decorated with instruments of torture, that have held an enduring fascination for scholars, artists and writers ever since their first publication.Footnote 50 Like the Ichnographia, there are two states of the Carceri, the first c. 1745 and the second, c. 1760; in the latter, the architectural structures have more complex forms. This change between states, from the lighter and more legible to the darker and more complicated, is the opposite of the simplification process that was taking place concurrently with the design of the carceres of the circuses in the Ichnographia. The facts of archaeology obliged Piranesi to rationalize his design of the carceres in his plan, while at the very same time he was adding structural and tonal complexity to his imaginary carceri. His use of the term in these two diverse contexts – antiquarian and artistic – should not be disregarded as mere coincidence and it might indicate a new direction for research. The Campus Martius plan, in its forms, meanings and historical contexts, has proved to be an enormously fertile ground for study and discovery; like its creator, it resists categorization. It obliges the scholar to set aside disciplinary limitations or preconceptions; it asks us to keep an open mind.