In response to the political and economic crisis that gripped central Europe in 1848, two young German men unknown to each other but who shared the name ‘Otto Dresel’ fled their homelands. Both harboured strong liberal ideals and feared persecution by the autocratic governments of the German states. One of them, an accomplished pianist, dreamed mainly of seeking his professional musical fortunes in a freer land. The other, while an able musician in his own right, had a more immediate and pressing motivation: he was fleeing a two-year prison sentence for high treason because of his involvement in revolutionary political activities. The two men arrived in the United States within a year of each other. Dresel the pianist eventually settled in Boston and developed a reputation as a respected performer, composer, teacher and music critic. Thanks almost exclusively to the musicologist David Francis Urrows, he is a relatively familiar figure among scholars of art music in nineteenth-century America.Footnote 1 The other Otto Dresel, by contrast, is barely known today and has drawn almost no notice in recent scholarship. He made his way to Columbus, Ohio, where he would marry, raise a family, embark on a legal career, and lead a busy if deeply chequered political and civic life. He was also zealously active as a musical amateur, and along with his musically gifted German-American family he deserves the attention of music historians. Indeed, their story bears on aspects of American music history that would be far less accessible through attention to a Boston luminary, namely the intimate and emotionally complex realm of family music-making. It can also serve as a case study in the musical experiences and activities of German-Americans in the mid- to late-nineteenth century.

A handful of biographical sketches, newspaper items, organizational histories and specialized studies, along with his own publications and a thin assortment of surviving letters, can allow us to paint a moderately detailed picture of this ‘other’ Dresel's career, as well as his civic and political engagements. Fortunately for present purposes they also reveal a good deal about his manifold public musical activities. Far fewer, on the other hand, are sources bearing on the more personal and private musical experiences he shared with his family at home. This paucity is unsurprising, since the most intimate performances are also typically the least well documented. One narrow but nonetheless evocative window into this otherwise largely hidden realm of performance is afforded by the serendipitous survival of five volumes of sheet music that had belonged to an Otto Dresel and two family members in the 1870s.Footnote 2 These ‘binders’ volumes’ were originally the products of personal selections and orderings, and were then professionally bound for their owners.Footnote 3 A first glance might easily lead one to associate them with the prominent Boston Dresel, whose large circle of contacts included the likes of Liszt, Mendelssohn and the Schumanns. But a closer look soon reveals that the volumes belonged to an altogether different man and his closest relations, who lived far from the ‘Athens of America’.

In this essay I explore both the public and domestic sides of this virtually unknown musical life, with particular attention to the latter aspect as reflected in the family albums. I argue that these two dimensions present a notable contrast of musical genres, moods and functions. Dresel's public musical activities, both choral and instrumental, followed patterns shared by many musically active German men of the Forty-Eighter generation. Their performances tended to stress civic virtues, happy fraternal bonds, and the celebration of German musical culture as an elevating, patriotic force in American civilization. Though by no means devoid of sentimentality, this was a largely male realm of affirmative, expansive ideals and commitments. The music he shared with his family at home, on the other hand, served notably different purposes. It was performed intimately, in an often melancholy and even mournful mode that reflected the need for personal consolation and was thus more in keeping with typical Victorian attitudes about the domestic, womanly sphere. The more we discover about the troubled course of Dresel's life, the better we can understand his growing need to take refuge in his home and family as well as in music that helped him and his loved ones deal – for a time, at least – with deepening feelings of regret, failure and loss. I propose that this marked contrast between the public and private sides of the Dresels’ musical lives points to a need for greater attention to the distinctive character and functions of intimate family music making in nineteenth-century America, especially during the years of widespread disillusionment and cultural reorientation that followed the Civil War.

***

The spread of German music and musicians in nineteenth-century America is a well-known theme in scholarship on music in the United States. Often this theme has been connected to the study of the development of German-American identity, but it has also been explored with regard to its broader and deeper cultural effects. Heike Bungert, Karen Ahlquist, Barbara Lorenzkowski, Mary Sue Morrow, Suzanne G. Snyder, and Christopher Ogburn, among others, have written about the Männerchor tradition and German-American singing festivals (Sängerfeste) throughout the country.Footnote 4 John Koegel, Jonas Westover, John Spitzer and Nancy Newman, in turn, have illuminated various aspects of the growth of instrumental music in the US at the hands of German immigrants, with attention to their swelling numbers in homegrown orchestras and to the tide of German ensembles that toured the country beginning in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 5 These and many other studies have established the ‘German element’ as a central feature of an emerging American musical culture. Nearly all, however, have focused on public musical events such as symphony concerts, choral concerts and festivals, and the like. Largely because of a scarcity of sources, very little research has been conducted on German-American music-making that was more hidden from view: that which was played in the home or in private settings, apart from larger public audiences.Footnote 6

Naturally, German-Americans who arrived in the mid-century wave experienced many of the same social and cultural transformations that were affecting the American public generally; indeed they had no small part in bringing about those transformations. Beginning in the second quarter of the nineteenth century – toward the end of which a deluge of German immigrants arrived in the US – the American sheet music industry exploded. Publishers regularly churned out songs, piano arrangements of opera arias and orchestral works, études, and other music for an eager and ever-growing number of middle- and upper-class consumers. Sheet music sales provided rapidly broadening access to a wide variety of music for many Americans. Studies of private music-making in nineteenth-century America have focused above all on the cultural significance of sheet music, much of which is generally (if sometimes misleadingly) termed ‘parlor music’, because it was frequently performed in private, domestic spaces – chiefly the parlour.Footnote 7 Nicholas Tawa's 1980 book Sweet Songs for Gentle Americans: The Parlor Song in America, 1790–1860 helped to launch the conversation on this crucial element of nineteenth-century musical life. Subsequent studies have pursued an enormous range of related topics, from the spread of pianos and piano-playing to middle-class homes, to lyrical meanings and sentiment in popular song, to minstrelsy and blackface iconography in sheet music publications, to the close association of parlour music with girls, young women, and the female-dominated domestic sphere more generally.Footnote 8

Only in the past couple of decades have scholars begun to draw attention to the special importance of the ‘binder's volume’ in nineteenth-century domestic musical experience, and particularly in the everyday lives of young women and girls. In a 1999 dissertation dealing with several large collections from across the country, Petra Meyer-Frazier discussed these volumes within the context of prior scholarly findings about nineteenth-century American women's lives. She showed that such albums represented far more than collections of ‘innocuous music’ meant to provide light entertainment for gatherings in the home. They reflect not only the ideals, values, tastes and desires of young, white, middle-class women, but also contemporary social expectations and idealizations of these young women.Footnote 9 The collection of Emily McKissick (1836–1919), the first binder's volume to appear in a facsimile edition (2011), offers evidence supporting these claims. According to Katherine Preston, the varied selections in this album ‘almost perfectly [encapsulate] the styles of music that were broadly popular among the American middle class at the midpoint of the century’.Footnote 10 Mark Slobin maintains that Emily's annotations, which include ‘fingerings, extra verses, harmony lines, and revealing marginalia’, evince key aspects of the young woman's social environment.Footnote 11

More recently, Candace Bailey has pursued close studies of binders’ volumes belonging to women in the antebellum South in order to illuminate the role of these assemblages in their owners’ private lives and larger social worlds. Bailey argues that such albums served as musical ‘commonplace books’, not only reflecting their owners’ tastes and predilections but teaching, guiding, and reminding young women about proper social deportment. Often displayed prominently in the parlour, the binder's volume also indicated to visitors that a young woman had mastered a socially mandated set of skills and behaviours.Footnote 12 Bailey's 2019 book extends this inquiry into bound and unbound music collections belonging to three young women from elite Charleston families in the antebellum era, showing among other things that these particular collections reflect their owners’ European travels and cosmopolitan orientation.Footnote 13 In a broadly complementary vein, Karen Stafford has studied the process of assembling such collections, gathering data from some 263 binder's volumes held at the Library of Congress. She calls attention to a ‘culture of collectorship’, investigation of which can illuminate important aspects of the owners’ family lives, memories, and ‘visions of the world’.Footnote 14

In an especially seminal essay of 2004, Ruth Solie discusses the central importance of home music-making, especially by adolescent daughters, to the emotional well-being of the nineteenth-century family as a ‘nuclear’ unit. She writes that ‘music was necessary to society, not as mere entertainment but … as a sort of combination spiritual therapy and mental hygiene’. The family group centred on parents and children ‘was the natural and proper locus for this Herzensbildung along with other kinds of education and [socialization]’. While the husband's central responsibility was to earn money in the public sphere, the wife and daughters were expected to cultivate the family's emotional and spiritual well-being within the private sphere, very often through music. This convention frequently placed a special burden on an adolescent daughter as the main purveyor of musical enjoyment, and thus as central to the affective life of the home. Solie shows convincingly that domestic music-making often became a form of family catharsis.Footnote 15

All of these scholars have contributed to an expanded and refined understanding of domestic musical life in the nineteenth century. Yet many hundreds of bound sheet music collections still await close exploration by historians of American music. Given the widely recognized influence of German music and musicians in the US starting in the mid-nineteenth century, our lack of knowledge about music-making in German-American households represents an especially notable lacuna. The Dresels’ volumes offer one starting-point in this realm, a case that is evocative at least partly because it included highly active male involvement in a space that has typically been characterized as female, and also because it offers insights into a family group.Footnote 16 Viewed in the context of other relevant evidence, the contents of these collections can prompt new questions about the specific functions of music as an intimate domestic activity, as well as about the role of German-Americans in cultivating such practices during an era marked by heightened feelings of melancholy and loss.

***

Our Dresel – Otto Friedrich Dresel – was born in 1824 in Detmold, then in the principality of Lippe, today in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia.Footnote 17 He studied law at Jena, and in the mid-1840s became caught up along with many other liberal, middle-class Germans in the revolutionary fervour sweeping central Europe. As editor of a radical-democratic publication and a leading political agitator he soon ran afoul of the authorities and was sentenced to prison. Dropping out of sight, he gained secret passage on a ship bound for Baltimore, arriving there late in 1849. After some two years of further legal study, English language immersion, and teaching music in Massillon, Ohio, he was admitted to the Ohio Bar and granted citizenship in 1852. The following year he settled in Columbus, where he practiced as an attorney until his death nearly 28 years later.Footnote 18 A handsome man of great energy as well as passionate commitments, he soon emerged as a prominent and highly engaged citizen, gaining respect not only within the capital city's rapidly growing German immigrant community but among the general population as well (see Fig. 1).Footnote 19

Fig. 1 Otto Dresel in an 1845 portrait by Julius Geissler. Lippische Landesbibliothek, http://www2.llb-detmold.de/html/BALP-5-31.html

In accord with the prevalent practice of endogamy in the German émigré community, in 1855 Dresel wed 19-year-old Marie Louise Rotthaas, the Columbus-born stepdaughter and heiress of a successful German-American beer brewer.Footnote 20 Their union of some 26 years was by all indications a thoroughly devoted one. In contrast to Otto's busy public involvements we find little to no evidence that Louise was active outside the family sphere. Following a typical middle-class pattern for her time, she devoted herself to supporting her husband and caring for a large household. The couple's first child, Otto, died just short of his fourth birthday in 1860; despite what we know about the high child mortality rates of the age, we will find reason to conclude that this loss affected the parents both permanently and profoundly. Another son (Herman, 1858–98) and four daughters (Alma, born 1863; Flora, 1865–1925; Clara, 1867–1900; and Marie Louise, 1872–1918) would live to adulthood. The children were raised in a traditional German domestic cultural environment that placed a high value on academic achievement along with musical activities.Footnote 21 By all indications Otto took on the role of paterfamilias in a well-established old-world mode, maintaining a clear separation between his domestic life and his engagements outside the home.

The world outside remained a turbulent and challenging realm for him. The democratic political convictions that had led him to confront autocratic rule in Germany also prompted Dresel to oppose what he saw as the threat of growing federal power in the US. He emerged as a strongly partisan Democrat, a supporter of Stephen Douglas and the doctrine of ‘popular sovereignty’. Elected as a representative of Franklin County to the Ohio Legislature in 1861, he soon created a furore by loudly supporting states’ rights, accusing the Lincoln administration of establishing a ‘military despotism’, and denouncing those who ‘in their hatred of slavery, propose to bury it under the ruins of the Constitution’.Footnote 22 Vicious public smears followed against his ‘Copperhead’ views and even his personal character. In 1863 his Republican opponents in the legislature publicly censured him as a treasonous promoter of ‘sedition and disunion’. Despite his re-election soon thereafter, he grew seriously disheartened by these political batterings, and he resigned from the legislature in late 1864.Footnote 23

Although the nasty conflicts and defeats of the war years damaged Dresel's reputation he continued to enjoy considerable public regard, especially among the German-Americans of Columbus and among Ohio Democrats. The scope of his undertakings was impressive. He offered a wide range of legal services and was probably a founding member of the Columbus Bar Association. His related activities included service as a notary public, a transfer agent for funds sent between the US and Europe, and a Master Commissioner of the Franklin County Court.Footnote 24 His expanding civic engagements included at least two terms on the Columbus Board of Education and helping to found the Columbus Public Library, of which he became a Trustee. He joined one of the two Masonic lodges in Columbus. In 1866, he became president of the Columbus People's Hall Association, which sponsored musical events, lectures, conventions and other public functions.Footnote 25 He was active as a writer of both fiction and non-fiction; numerous poems, essays, songs, and at least one novella came from his pen, appearing mostly in German-language newspapers and periodicals.Footnote 26 A gifted orator, he was frequently invited to address Democratic party functions around Ohio, and he also spoke at numerous cultural gatherings, including an 1877 meeting of the German Pioneer Society of Cincinnati. Later he would be profiled in this group's publication, Der Deutsche Pionier, which celebrated the lives and exploits of leading German Americans.Footnote 27

***

Beyond his career, political and civic involvements, Dresel became passionately occupied with a variety of public musical activities. Only months after settling in Columbus, he became the conductor of the city's Männerchor (men's choir), characterized by one source as ‘the most prominent cultural force among the Columbus Germans’, and he remained intimately involved with this group at least until the early 1870s. He would be chosen as president of the North American Saengerbund, in which capacity he coordinated and oversaw the operations of some 22 mainly midwestern German singing societies from the 1860s to the early 1870s. In this office he served as the leading organizer and host of a national Sängerfest held in Columbus in 1865, among the first such events since before the Civil War and a major affair even for this busy state capital. His selection to lead the festival was hotly criticized because of the political positions he had taken during the war. Nonetheless he announced this event as promising ‘a great chorus of Union, Harmony, and Reconciliation’, and his welcoming speech to the assembled groups was a passionate call to German-American singers to fulfil their ‘holy mission’ in the service of freedom and national fraternity.Footnote 28

Fig. 2 Directors of the Columbus Männerchor. Otto Dresel appears in the second-highest row, second from the right. I have been unable to determine the date of this image, but it cannot have been created before 1900, when Theodore Schneider (fourth row down, left) served as director of the Columbus Männerchor. ‘Columbus Maennerchor Directors’, Columbus Memory, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/memory/id/48219/rec/2

These singing festivals marked the continuation of an already well-established German tradition. They have been characterized as ‘an inherently male space’, offering both singers and the men in their audiences respectable public venues for happy sociability, beer-drinking, Gemütlichkeit and pride in German culture. Christopher Ogburn argues that the societies that organized these assemblies had an inherently defensive aspect at a time when the massive influx of Germans into the US evoked powerful waves of nativism. These singing clubs ‘demonstrated the fraught place of German Americans in the ever-evolving concept of American identity’, yet at the same time they promoted ‘the emergent connection between “Germans” and music’.Footnote 29 The Männerchor thus served as a support group that afforded a needed sense of community while also projecting a positive public image of German-Americans. For Dresel and other German-born Democrats who had been denounced as virtual traitors, the 1865 Sängerfest in Columbus supplied a nearly perfect opportunity to declare their loyalty to the Union in a highly visible way, even as they furthered a much broader task, that of uplifting Americans by means of musical culture.

Indeed, as one contemporary noted, among the main public goals Dresel set for himself was ‘the spiritual elevation of the people through song and music’.Footnote 30 In the mid-1850s, just as his participation in the Männerchor grew busier, he began both playing violin and singing in a group called the ‘German Quartette Club’. In 1859 he founded and began performing with a small orchestra called the ‘De Beriot Club’, named in honour of the Belgian violinist, composer and teacher Charles Auguste De Beriot, which aimed to ‘encourage and cultivate the taste for music and social enjoyment’. Dresel was evidently the leading member, serving as the ensemble's permanent president. This group of men seems to have performed most frequently the chamber music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, often at the homes of its members, but notably also at unpaid local events including graduations and fundraisers to benefit various charities.Footnote 31 His public concert activities were clearly tied to a sense of social and civic responsibility to his adopted country.

In this regard Dresel exemplified the mid-century influx of Germans who greatly accelerated the spread of their native music in the US, not only through performance but through strong advocacy as well.Footnote 32 He felt that he shared with other European immigrants – especially those from the German lands – a positive obligation to promote his cultural heritage. In his 1877 speech to the Pionier Club, he could hardly have stated more clearly his ambitious sense of mission for German music in the New World:

As far as the German tongue is heard, so too sounds German song. It accompanies us across the sea, it follows us into the Western wilderness. It is the herald of our joy in life, our comforter in suffering and trials; it rejoices with us at our happy feasts and cries with us at the graves of our loved ones. It is the trumpet that knocks down the walls of the Nativist Jericho; it is the bridge over which our German life and character penetrates the American family. Just look at the past! You'll remember the times when the Americans had no other songs but ‘Old Hundred’ and ‘Yankee Doodle’, and no instrument but the banjo. How totally different it is now! The tones of the piano sound in every house; Beethoven and Mozart have become familiar everywhere; Thomas with his chorus moves through the land like a triumphant conqueror! And thus it is that German music has fully penetrated into civic life, that the fingers, the hearing, the taste of the Americans have been so far edified. This is a German accomplishment, of which we may all be rightly proud. And the glorious work that we have begun we must carry on; indeed we must complete it.Footnote 33

Notable here is that, in Dresel's eyes, the musical traditions and culture of his native land had a crucial role to play both in the realm of family life and in the general progress of American civilization; indeed he depicted these two dimensions as intimately related.

Such declarations represented a phase in the process by which German-Americans came to define their place in American society. According to Kathleen Neils Conzen, through the mid-century decades German immigrants hoped to maintain a separate ethnic identity based on a sense of cultural superiority even as they embraced the melting-pot ideal and disavowed notions of political or social separation.Footnote 34 Ogburn succinctly characterizes this outlook common to many educated German-Americans: ‘it was the duty of German immigrants to instill “culture” into their new home while never forgetting their roots’.Footnote 35 Conzen sees this ideal already on the wane in the years following the Civil War, replaced by a more resigned acceptance of cultural pluralism and a separate ethnic identity. Despite the positive ebullience of his 1877 speech, a number of signs suggest that by the last years of his life Dresel was beginning to lean toward this sort of resignation. As he struggled with mounting pressures and setbacks both personal and professional, he reportedly felt a deepening disillusionment with America.Footnote 36 While he left no explicit record of any such change in perspective, in the end his actions may have spoken louder than his words.

***

Beneath the busy professional, political, civic and public musical engagements of Dresel's life lay a deeply troubled soul. His life ended suddenly and tragically when on 5 January 1881, he killed himself by a gunshot to the head while alone in his office. His eldest daughter Alma reportedly suffered the trauma of finding the body in a pool of blood. According to several newspaper accounts, he left a note in which he expressed profound despair: ‘Here sit I again in my lonely office – I want to think but cannot – weakness of old age, devoid of sense – No business, no task, no friend, no prospect. One thing only remains to me – my family – all, all. My guilt, my guilt. Frightful. Darkness in my head – as if in prison. Air! Air! A…’. The news shocked Columbus; many struggled to grasp why this prominent citizen, a husband and father of five – his youngest daughters were only 8 and 12 – would take his own life. A writer for the German-language newspaper Der Westbote, who knew him well, warned against too-easy moral judgments: ‘Who can solve the puzzles of the human heart?’Footnote 37

Both English- and German-language accounts of his suicide asserted that money troubles were not a major cause of his despair, yet we have evidence to suggest that they did at least play some role.Footnote 38 The panic of 1873 had brought on an economic depression that lasted through most of the decade. Otto's career suffered and never fully rebounded; meanwhile several of his investments collapsed. In 1874 he and Louise vacationed in Germany for several weeks, leaving their children at home; the trip shows all the earmarks of an escape from mounting pressures. His physical health took a rapid downturn in the mid-1870s, further harming his professional life; the fullest account of his demise states that over his last years Dresel ‘had little work to do as a lawyer’.Footnote 39 His main effort at published writing, the semi-autobiographical novella Oscar Welden, was a near-total failure financially.Footnote 40 More direct testimony to money troubles is at hand: in the spring of 1878 he placed newspaper advertisements in a patently urgent effort to sell his family residence.Footnote 41 Yet apparently the home was not in fact sold, and published post-mortem assessments concluded that the financial worries existed more in Otto's mind than in his actual circumstances.Footnote 42

The roots of Dresel's despair appear to have gone far deeper than financial woes, deeper also than the palpable losses and discouragements he and Louise had suffered beginning with the death of their first child, and deeper than the mounting disappointment he reportedly felt about American politics and the nation itself.Footnote 43 Already as a young man newly arrived in the US, his writings showed an unusually morbid streak, as for instance in an 1850 poem titled ‘To Live and To Love’ (Leben und Lieben). What is our life, he asked? A restless striving for a shiny nothing. What is love but a bitter draught of tears? And so,

Similar expressions of gloom continued into his later years. He wrote that by the mid-1870s life had become a burden to him, ‘because I became a burden to myself and to others’.Footnote 45 His 1876 novella Oscar Welden concluded forebodingly with the stabbing death of the alter-ego protagonist by a spurned German lover, who then fatally stabs herself. It would not be a hard leap to find here the expression of inescapable, even congenital feelings of sorrow and self-accusation.

According to the Westbote writer who reported on his suicide, his depressed state had for several years been ‘quite generally recognized’ by those who knew him. He had long suffered both physically and emotionally, such that he was driven first to melancholy, then to utter despair. Meanwhile ‘he withdrew, perhaps misguidedly, from all public engagements, and sought distraction and comfort only in his family, who showed the greatest love for him’. Most significantly for our purposes, the same source reported that he had ‘pursued music within his family with great pleasure’; indeed ‘music was the only means that could raise him out of his melancholy brooding’.Footnote 46 In the end, not even the harmonies of home and loved ones could save him from a crushing sense of sorrow, failure and guilt. But through the decade of the 1870s, amid mounting disappointments, declining health, and the fading of his faith in America, his domestic world would grow more crucial as his main source of emotional comfort.

***

Our volumes by themselves leave no doubt that in addition to his many involvements outside the home, Otto encouraged and took frequent part in domestic performances, playing music for violin with piano accompaniment and singing with his family as well. His wife Louise seems to have shown considerable keyboard proficiency, and almost certainly played often as accompanist to her husband's violin. Like Otto, Louise was also a singer, most likely a soprano; in light of Otto's own obvious love of vocal music and the evidence to be explored in the family volumes, we can presume that her gifts as a vocalist were likewise far from minor. Although we have no concrete evidence that Louise ever had formal training, it is obvious that both husband and wife had been raised in families that exposed them to extensive lessons, and they clearly wished the same for their own children. It is also more than probable that the two played together before they were married; such activity was warmly encouraged for courting couples in this era.Footnote 47

Otto sought out serious musical instruction for his surviving son Herman, and found it in the person of ‘Professor’ Hermann Eckhardt, a fellow Forty-Eighter and violinist who had played under no less a figure than Richard Wagner in Germany, then briefly with the Germania Orchestra in the US as well as with the other, far more renowned Otto Dresel in Boston before landing in Columbus.Footnote 48 Herman played in a string quartet composed of the sons of members of his father's ensemble, the De Beriot Club, and with this and other groups he sometimes performed at public occasions. We can fairly surmise that as the eldest living child he took frequent part in family music-making as well.Footnote 49 Herman's next sibling, Alma, was born around 1863, and as a young adolescent she had already emerged as quite an accomplished pianist; she would later perform at her high-school graduation. Clara too would become admired as a pianist and vocalist. The youngest of the sisters, Marie Louise (affectionately known as ‘Lulu’), took up the violin rather than piano, an openly progressive step at a time when the traditional taboo against female string players was only beginning to loosen; in fact she would be later noted as a highly accomplished player who performed in high-profile concerts. While evidence regarding the musical activities of daughter Flora has thus far remained elusive, it is clear that the Dresel home was rich in aptitude as well as demonstrated musical talent.Footnote 50

Of the five family volumes in question, two are identified as Otto's, two as Louise's, and one as daughter Alma's. As a violinist, son Herman must have had his own set of scores, but our set includes nothing from him or from the younger children. Unfortunately, we also do not know just when or even how the various scores were obtained, but they were most probably purchased singly or in smaller sets during the later 1860s and the early to mid-1870s. Most were from German or other European musical publishers, and some may have been ordered directly from those firms. But many would have been available through American outlets, including several much-advertised music shops in the City of Columbus; indeed a number of pieces carry stamps identifying two major local music dealers. All of the volumes appear to have been bound at the Dresels’ request by the same Columbus bookbinder, possibly at different times but in no case later than the mid-1870s.Footnote 51 Having them formally bound was itself a clear statement of the family's investment in its music.

***

Otto's two albums form a twin set and constitute quite a rarity among nineteenth-century American binders’ volumes: they were compiled by a man, and rather than songs and piano music, they contain music for violin with piano accompaniment.Footnote 52 One volume includes the violin parts; the name ‘Otto Dresel’ appears on the first sheet of nearly all these scores. The other is made up of the corresponding piano accompaniments. On the inside front cover of the book of violin parts, ‘Feb 16, 1872’ is written in pencil; this inscription provides our best evidence of the date Otto's volumes were bound. Seventeen composers are represented altogether. Although it is difficult to tell when the editions included here were issued, all of these works were originally published in the 1840s or earlier. A number of the scores are well-thumbed and were evidently used frequently. Several of the violin parts were marked up, presumably by Dresel himself, to indicate fingerings, bowings, and other points of technique and emphasis. We can be virtually certain that the volume with piano parts was mainly for the engagement of Louise as accompanist, but it might also have been used by Alma as her skills advanced through the 1870s.

The set of composers and works represented in Dresel's collection reflect a typical middle-class aesthetic of the mid-nineteenth century, though one reflecting a pronounced European, especially German bias. The selections show a broad internationalism and eclecticism of taste, from German abstract instrumental works to fantasies and potpourris on Italian and French operas. A majority of the pieces are arrangements from opera for violin and piano, and thus nicely suited to home recitals by husband and wife, father and daughter, or brother and sister. One is the overture to Le Calife de Bagdad by the French composer Francois-Adrien Boieldieu, while the rest are adapted from works of the first half of the century by Donizetti, Bellini, Rossini, Auber, Meyerbeer, Flotow and Spohr. Dresel's operatic selections demonstrate that the melodies of opera pervaded nineteenth-century instrumental music to an extent we have trouble appreciating today.Footnote 53

The most extensive of these operatic selections were sourced from the Bohemian composer Leopold Jansa's Op. 60, Der Junge Opernfreund. These pieces, which Otto labelled ‘selected melodies’ in a handwritten table of contents, were first published in the 1840s; they enjoyed the height of their European currency through the middle years of the century. Jansa's Op. 60 comprises melodies or variations on selections from 32 operas, only five of which appear in Dresel's collection: Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore, Belisario and La fille du regiment, Flotow's Alessandro Stradella and Bellini's La Sonnambula. Such works typified the music that had most likely surrounded and shaped Dresel during his adolescence and young adulthood. Flotow's Stradella, the only one of these five by a non-Italian, had become an especial favourite in the German lands, where Otto had undoubtedly heard it performed or at least heard some of its more famous passages in arrangements.Footnote 54 The Jansa selections thus represented the quite deliberate importation of popular pieces Dresel had already known well in his youth.Footnote 55 Playing them privately in the 1870s was to some extent a self-indulgent exercise in nostalgia for him – a nostalgia that he could indulge with minimal restraint at home.

As fond as he may have been of these pleasing adapted melodies, however, Dresel gave overall priority to original works for violin that were of a generally more sombre character – in some cases emphatically more. These were by nineteenth-century composers who achieved renown in their own time but in most cases suffer near-total oblivion in today's performance repertory. The first scores in the volume are the ‘Elegie’ by the Moravian violinist Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (1812–1865), and ‘La Mélancolie’ by the Belgian François Prume (1816–1849). These are followed by the ‘Sonate Op. 12, No. 2’ by the German Friedrich Wilhelm Kücken (1810–1881); farther along in the order are an ‘Air Varié, No 7’ by the Belgian Charles de Bériot (1802–1870), and the ‘Rondo Concertant’ Op. 50 by the German Aloys Schmitt (1788–1866).Footnote 56 Dresel's favourite work in the entire volume seems to have been Ernst's ‘Elegie’, judging by its prominent opening placement in the volume, the well-worn paper, and the number of markings on the music. This piece, to be played ‘Adagio melancolico ed appassionato’, calls for uncommon musical sensitivity and technical prowess. Several passages require the performer to shift suddenly into sixth position, high on the fingerboard. Perhaps most impressively, an eight-bar passage includes notoriously difficult consecutive double stops of thirds, sixths and octaves.Footnote 57

Already an advanced violinist when he came to America, Otto clearly continued to practise, indeed to challenge himself, throughout his life. His love of his instrument was passionate. In an essay of 1877 he extolled the violin as ‘the soul of the orchestra, which with its strong, lovely sound competes with the human voice better than any other instrument, and is able to express the most secret feelings and moods of the heart’.Footnote 58 Revealing his own aspirations to technical mastery, he proudly purchased his own violins from the German-American luthier Georg Gemünder, whom he ranked alongside the greats of Cremona. The priority he gave to a daunting composition such as Ernst's Elegie was undoubtedly a reflection of this same ambition (Fig. 3). Indeed though the 1840s and 1850s Ernst was widely regarded as among the greatest performers in Europe and a worthy heir to Paganini, who had died in 1840; he was thus a model whom any gifted amateur violinist might have sought to emulate.

Fig. 3 Handwritten cover sheet for Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst's ‘Elegie’ in Otto Dresel's volume of violin parts. Property of the author.

Yet while Dresel apparently loved playing and took personal pride in his instrument and his skill, he was not a professional musician, and he showed no desire to be judged by such a standard. Evidently the works he gathered for his personal album were ones that he loved and wished to practise at home, without risking comparison with artists who performed regularly for the public. His choices were no doubt guided partly by his desire to play with his wife's or daughters’ accompaniment, yet in this regard the available possibilities were nearly endless. Again, it was above all his close identification with the music of his own past that shaped his collection. Ernst, Kücken, Schmitt and the others in this group were all at least half a generation older than Dresel, and all had flourished during his formative years. Together with operatic works such as those in Jansa's collection, pieces by these composers allowed Dresel to revel in the music he associated with his youth in Germany, which might help him escape from the depressing realities and experiences that chequered his life in the 1860s and 70s.

Dresel's prominent choices suggest even deeper needs than a nostalgic longing for escape. Ernst's Elegie was described by a contemporary critic as a piece ‘full of the purest, deepest soul-suffering [Seelenschmerzes]’.Footnote 59 In 1859, recognizing the work's power and popularity, the German-American writer and Forty-Eighter Otto Ruppius sketched a tragic if probably fanciful story of the ‘origin’ of the Elegie, involving the heart-wrenching death of the composer's young beloved. In any case, commentators clearly understood the work to reflect a profound grief.Footnote 60 Prume's ‘La Mélancolie’, which came next in the volume, is a somewhat less heavy but nonetheless doleful tune.Footnote 61 As we noted earlier, Otto and Louise lost their first child, the young Otto, at the age of four in 1860. The effects of this personal and familial tragedy were unlikely to have been lessened by the subsequent years of civil bloodshed, when Dresel became embroiled in vicious political battles in which he was publicly denounced in exceedingly abusive terms, and which drove him out of public office. We have seen that the decade of the 1870s brought further troubles, including a faltering career and serious financial worries. All this together with evidence suggesting a strong congenital leaning to depression helps explain why his home and family would become more and more a refuge for him. While Otto's participation in and promotion of the Columbus Männerchor and other singing groups stressed patriotism, German cultural pride, fraternal warmth and bonhomie, and while his string ensemble aimed to cultivate musical appreciation in his community, the music he played privately at home with his wife and children likely provided one of his few ways of expressing a profound and abiding sadness, even as it offered personal comfort.

This impression gains weight when we explore the two volumes belonging to Dresel's wife Louise, the most substantial and in some ways the most personalized books of the five in our set. The cover of the first is emblazoned with ‘Louise Dresel’ in gold lettering; the second carries an even more prominent and elegant name plate: ‘Mrs. L. Dresel’. The size and relatively elaborate character of these volumes reflect Louise's status in the nineteenth-century gender hierarchy. Her roles as wife and mother made her the anchor of the domestic sphere, and probably ensured her involvement in most if not all household performances. Moreover, as a woman confined mainly to the home, she undoubtedly considered music a primary, indeed essential emotional and creative outlet. Unlike her husband, she probably never performed publicly, although she may have played and sung at least occasionally for friends and visitors. Notably, though she was American-born she seems to have had no interest at all in American composers, and in fact seems to have eschewed them completely. Her volumes consist entirely of European vocal music along with pieces for piano by German and Italian composers, several of which would have demanded no little talent and practise, both vocal and instrumental.Footnote 62 We cannot know whether or how far her choices were influenced by her husband; indeed, the likely strength of Otto's influence as paterfamilias should not be overlooked. But in general Louise's collections reflect considerable musical independence and sophistication. She evidently saw herself as capable of meeting the demands and capturing the subtleties of the most highly regarded exemplars of the European art song tradition.

Fig. 4 Front cover of one of Louise's two volumes. Property of the author.

Louise's tastes, much like Otto's, were varied. She obviously enjoyed opera arias and popular songs, which make up the bulk of the music in her first volume. In this collection of 42 pieces, many of which are specific choices taken from larger published assemblages, the vast majority are by German composers, although selections from Italian opera are sprinkled throughout. The latter include adaptations of famous arias from Verdi's Ernani, as well as Donizetti's La Favorita, Don Pasquale and Lucretia Borgia. The German composers represented here are rarely performed today; they include Franz Abt, Carl Krebs, Wilhelm Speier, Carl Keller and Carl Reissiger, among many others. Louise seems to have been especially partial to the music of the prolific F.W. Kücken, one of whose sonatas we found in Otto's volumes. Kücken's music tends toward the highly sentimental, with titles such as ‘Dearest Sweetheart’ and ‘Gently Rest’. He is known today mostly for having claimed authorship of the song ‘Ach, wie ist's möglich dann’ (‘Ah, how is it possible?’), a tuneful ballad popularized throughout the modern West in the twentieth century by Marlene Dietrich, and recorded in 1926 by the Austrian tenor Richard Tauber.Footnote 63 Other German songs in Louise's collection, such as ‘Lovely Smiles the Golden Morning’ by Carl Keller, ‘Home’ by Abt and ‘Die Heimath’ by Krebs, are redolent with this often saccharine style. Two of these selections came from a series of songbooks called ‘Gems from the German’, which also included works by Mendelssohn, Haydn and Weber along with many others, and proved popular among buyers of sheet music around mid-century.Footnote 64 Louise's aspirations as a pianist are evident here as well. Of the 42 selections in this volume, eight are works for piano, including arrangements for four hands of the famous variations on ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ by Henri Herz, a theme from La Sonnambula by Bellini, and – far from least notably – Beethoven's lugubrious ‘Marche Funebre’.

Ten of the pieces in this volume are not published editions, but manuscript scores in at least four different hands. Louise may have received some of these manuscripts as gifts from friends in her community, or she may have produced them herself in Columbus. Possibly Louise or Otto copied several of them, or had them copied, during the couple's time in Germany in 1874. Seven of the handwritten scores are bound consecutively and are in the same hand. None of these seven songs appeared frequently in American binder's volumes, most likely because published versions were not easily available in the US. All but one of the identifiable songs are in German and by a German composer; here again the complete absence of American compositions is notable.Footnote 65 It is also worth noting that at least four of these handwritten scores are songs intended for male voice; whoever took the time to write them out no doubt envisioned Louise accompanying her husband on the piano while he sang.

Two interrelated themes come to the forefront when we survey Louise's songs in this volume as a group. First, nearly three-quarters of the composers in the volume are German; the other quarter mostly Italian and French. A large proportion of the German works are either folk songs closely associated with German culture, or songs expressing yearning for one's native land. For example, Louise chose to include Abt's ‘Home’ in an edition bearing both German and English lyrics that describe the home country as a ‘parent land’, the ‘nurse of all our kindred band’. Similar songs in this volume include Carl Krebs's ‘Die Heimath’, whose lyrics praise the beauty of the homeland; and Krebs's ‘Der Deutsche Rhein’, part of a wave of patriotic Rheinlieder composed in 1840 after the French threatened to annex all German territories west of the Rhine.Footnote 66 While Louise was American-born, her selections attest to her staunch identification with the German heritage and community that surrounded her, at the centre of which stood her husband and family. But we have no evidence that Louise had ever been abroad before her 1874 trip with Otto, and her physical separation from an ancestral land only dreamed of or briefly visited may have evoked or reinforced a forlorn sense of displacement and alienation in her. Indeed the lyrics of several others of her German songs, such as Reissiger's ‘Zigeunerknabe im Norden’ and Kalliwoda's ‘Zigeunerlied’, use the archetype of the perpetually wandering gypsy to express the despair of exile and homelessness.Footnote 67

Second, a significant number of the songs in this volume show strikingly woeful lyrics. ‘Love Not!’, by the British composer John Blockley on a poem by British poet Caroline Norton, warns hearers never to love another, lest the beloved should change or die. Conradin Kreutzer set Johann Ludwig Uhland's ‘Die Vätergruft’, a poem describing a knight who has entered a dark chapel to lie down in a crypt and join his dead ancestors. Karl Curschmann's heart-rending ‘Der Schiffer fährt zu Land’ sets a text by the celebrated poet Friedrich Rückert; here a ship captain comes ashore anxious to marry his betrothed, only to realize that the bells he hears convey that she has either died or married another.Footnote 68 These latter two pieces were among the handwritten scores included in Louise's volume. That so many of the songs she selected present such somber lyrical content suggests that much like her husband, she found in private family music-making a vehicle for emotional or even mournful release, as well as for intimate exchange.

The larger of Louise's two volumes is devoted exclusively to lieder and ballades by Schubert, poems set to music for one voice and piano accompaniment. These pieces were not individually chosen by Louise herself; rather they made up the first three volumes of a six-volume set – advertised as the first ‘complete and authentic edition’ of Schubert's works – published by Ludwig Holle at Wolfenbüttel during the late 1860s or early 1870s.Footnote 69 The production is impressive, easy to read, and includes both the original German lyrics and French translations for most but not all songs. ‘Mrs. L. Dresel’ appears again in handwritten form at the bottom of the opening title page. Each of the three Holle volumes includes a table of contents in which someone, presumably Louise herself, has underlined a number of titles; most of these same titles also appear handwritten on a lined sheet bound among the volume's opening leaves. The underlined titles correspond fairly closely with 36 individual scores clearly identified with one, two, or three large pencilled ‘X’ marks. Since the three Schubert volumes that make up this collection include well over 200 songs, these marks represent meaningful discriminations.

Perhaps surprisingly, Schubert's works were rarely included in binders’ volumes of the period. German art songs of this strain, which often proved challenging to amateur performers, were evidently not among the parlour pieces for which collectors typically showed a preference.Footnote 70 More relevant here is that even in light of that era's culture of emotional overflow, a striking number of the lieder specially identified by Louise, above all those with two or three ‘X’ marks, are songs with verses of a decidedly mournful character. Louise highlighted relatively few of the many feeling-filled poems about faith, adventure, the beauty of nature, or frustrated love; rather the prevailing theme was death, and often the loss of a loved one. While their verses were taken from a wide variety of Romantic-era poets, lieder such as ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’, ‘Der Unglückliche’, ‘Klagelied’, ‘Der Tod und das Mädchen’, ‘Der Wanderer’, ‘Im Haine’, ‘Die Junge Nonne’, and ‘Des Mädchens Klage’ shared a tone of deep bereavement, even graveside pathos. Von Meyerhofer's ‘Schummerlied’ offers sadly suggestive words about a boy borne away by nature and the ‘god of dreams’. ‘Sei mir gegrüsst’, with verses by Friedrich Rückert, is a heartrending call to a dead child:

And it surely bears noting that Louise's clearly marked selections in this published collection include one piece that she also chose for her first volume, namely Schubert's setting of Goethe's ‘Der Erlkönig’. Perhaps not coincidentally, the top-right corner of the first page of the ‘Erlkönig’ score is folded in, the only such case in this large volume. Although other circumstantial evidence about Louise's life is scarce, we have reasons to suspect that her choices reflected feelings of grief shared with her husband: perhaps first and foremost the inescapable sorrow of having lost her first child at the age of four: ‘das Kind war tot’.

***

Biographical records on the surviving Dresel children are barely less patchy than those we have for Louise. But from Alma we have a personal sheet music collection that can give us a fuller picture than we might otherwise possess, at least in regard to her teenage years. Her volume appears to have been bound when she was around 13 or 14 years old: to gather together the separate scores, the bookbinder created a spine from the Ohio State Journal dated 26 October 1876. As with Louise's volumes, the young musician's name adorns the front cover in gold lettering. Along with the character of several of the included selections, this sort of personalized identification implies a role for Alma's own preferences in compiling the collection. But other features of the assemblage suggest that her parents or an instructor may have been involved as well; instructional studies and technical exercises represent a significant portion of Alma's sheet music. While it is possible that Louise was her main or even her only teacher, the presence of these exercises makes it more probable that like her older brother Herman, she was assigned to formal lessons.

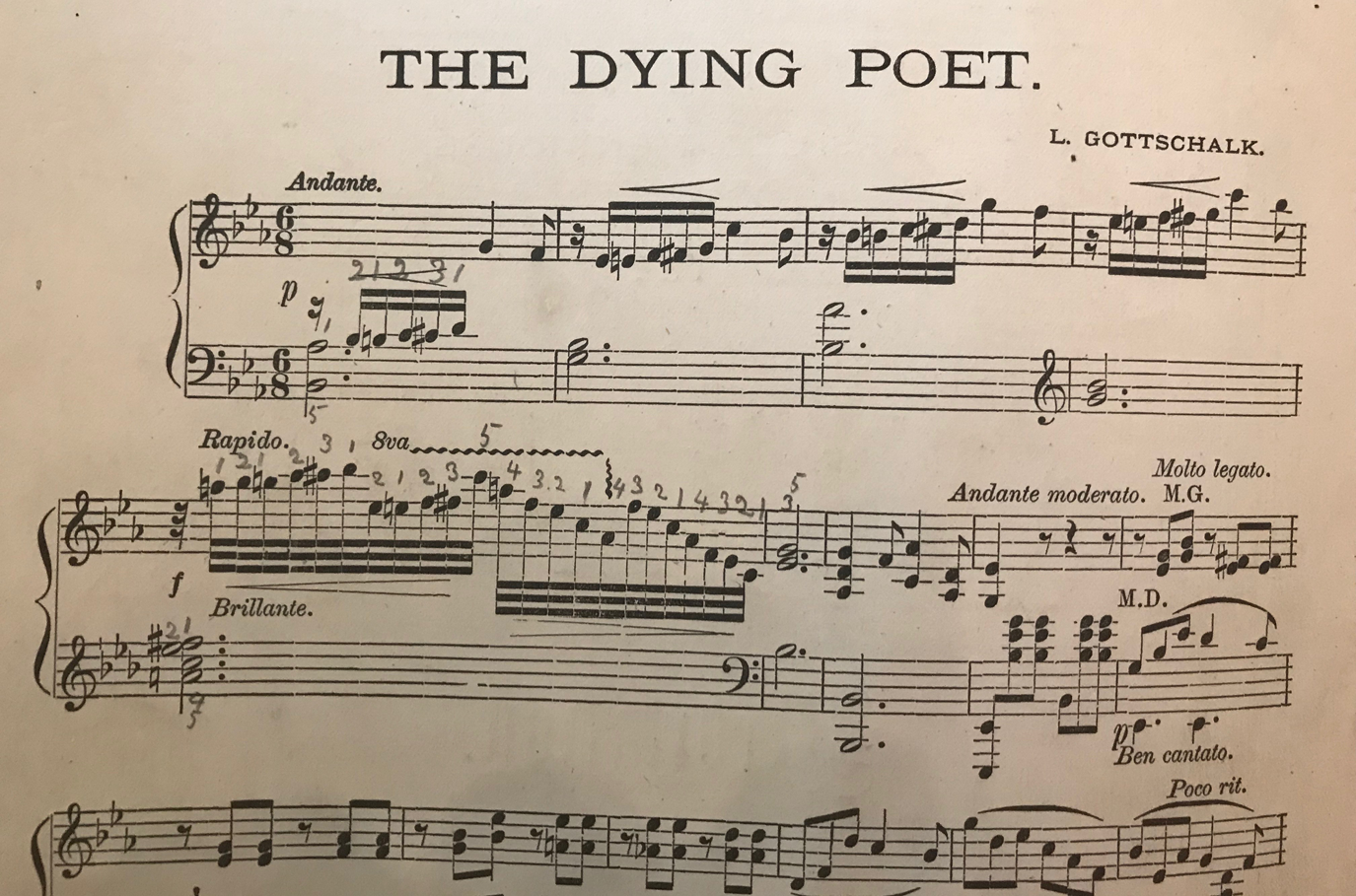

The exercises include several by the industrious German composer of student works Heinrich Lichner, as well as long sets of studies by Carl Czerny. Of the five such instructional series in Alma's volume, three have numerous fingerings and other markings written in, suggesting that the young woman showed dedication to improving her keyboard technique. Original works for piano include pieces by Louis Moreau Gottschalk, the Welshman Henry Brinley Richards, the Dane Friedrich Kuhlau, and Germans Heinrich Lichner and Beethoven. Each of these scores except the Beethoven include extensive pencilled markings, which reinforce our sense that Alma pursued serious technical ambitions. In this regard, Alma's inclusion of Beethoven's Piano Sonata Op. 31 No. 3 (‘The Hunt’) is particularly significant; this work requires considerable technical prowess. Whereas countless other binders’ volumes belonging to young women included waltzes and other light works intended for amateurs and sometimes (usually speciously) attributed to Beethoven, Alma's volume contains an original composition by Beethoven intended for his own virtuosic performance.Footnote 72

The works by Gottschalk, Richards and Lichner, among others, carry vividly illustrative titles, and would have appealed to many girls and young women of Alma's generation who were steeped in idealized Victorian imagery. The first piece in the volume, The Dying Poet, is a highly sentimental work by Gottschalk, the only American composer we find in any of the Dresel family's collections (Fig. 5). This meditation was performed in public to great success in the 1860s and afterwards, and the placement of this work with marked fingerings and articulations at the very start of the collection argues for Alma's awareness of and participation in popular musical trends in the United States. Significantly, however, her copy of The Dying Poet is of the original work, not an arrangement intended for amateurs, of which many were produced.Footnote 73 Especially in this version, The Dying Poet very rarely appeared in contemporary binders’ volumes; this was no score for amateur entertainment. Mastering this piece allowed her to liken herself to the most famous pianist in the Americas at the time, and to demonstrate her ability to play his virtuosic music. Alma's choice to include the work in her album thus points both to her seriousness as a musician and to her identification with the work's strongly emotional aspect.

Fig. 5 Alma Dresel's copy of Gottschalk's The Dying Poet, Boston: Ditson, 1864 (mm. 1–9). Note the pencilled fingerings. Property of author.

Along with several of Alma's other selections, this piece also echoes the suggestions of mournfulness in the collections of her parents; had the daughter inherited from them, or absorbed, a general familial sadness? Again, we might view The Dying Poet as an entirely typical expression of the Victorian sentimentalism that pervaded the literature and parlour music of this period, a sentimentalism that many contemporaries thought especially appropriate for women and girls. Yet in light of the personal tragedy and troubles Otto and Louise had endured, as well as the nature of their collections and other circumstantial traces of the family culture, it was arguably no accident that Alma gave priority to a composition of such pronounced melancholy.Footnote 74 Among the other selections that she placed early in her volume is an adaptation of an aria from Donizetti's Linda di Chamounix, an operatic tale of a young woman who is saved from madness by music.Footnote 75

Was Alma thus the family's ‘girl at the piano’, the adolescent daughter who bore disproportionate weight in the musical as well as emotional life of the home? While we have no direct indication that she became the key musical figure in the household, we certainly have some signs of her valued role; her evident serious practice, technical facility, and ability to accompany a soloist must have pleased her parents. And when considered alongside the musical choices of both Otto and Louise, the prominence Alma afforded works such as The Dying Poet speaks to her active participation in a home environment shaded by pathos. If she was not the main vessel for family musical catharsis, she was at least an important one. As some final biographical details will help to show, neither she nor her siblings were likely to have remained untouched by a deep current of familial sadness.

***

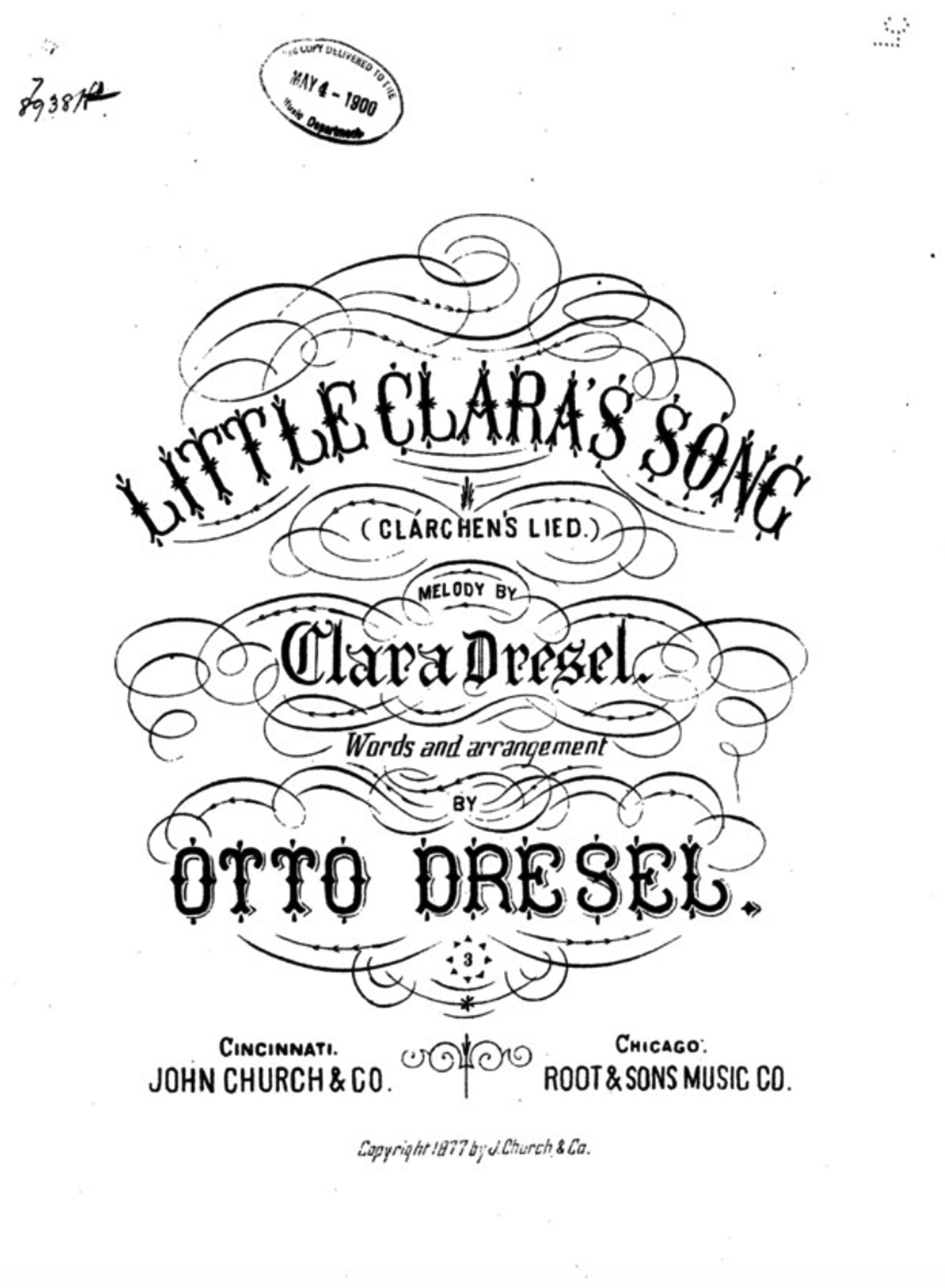

The Dresels left to posterity at least one other musical memento, one that had its origins in an intimate family moment. In 1877, Otto published ‘Little Clara's Song’, a very short work of only 19 bars for treble voice with piano (see Fig. 6 and Ex. 1).Footnote 76 On the title page he credited his young daughter with the melody. A brief explanatory note appears directly above the score:

During the brief absence of her parents, little Clara, but six years old, composed this air. Sitting in her chair rocking, and weeping at thought of the dear ones far away, she sang it over and over amid her sobs. Touched by its tender pathos, on his return home, her father set the melody to appropriate words, and put it into its present shape.

As noted earlier, Otto and his wife Louise had taken a trip to Germany without their children in the summer of 1874, when Clara would indeed have been six years old. Evidently Clara conceived this little tune, or something approximating it, while her parents were gone, and upon their return Otto composed lyrics and an accompaniment, publishing the piece several years later. He decided to set the song in F major, presumably matching Clara's vocal range. The vocal melody, in triple metre, is entirely diatonic save for a chromatic climb up through C#, and it is straightforward except for a rather awkward downward leap of a seventh, from F5 to G4. The song has several distinctive, even strange features, however. It begins with a full seven bars of piano introduction. Despite the vocal line's scoring in F major, this introduction seems to begin in F minor and proceeds through a bizarre partial modulation to G minor before finally establishing F major in the bar in which the vocal line begins. The harmonic instability of these first seven bars, along with the winding, unrelenting chromatic triplets in the right hand of the piano, lends a sense of unease, perhaps even dread (see Ex. 1).

Fig. 6 ‘Little Clara's Song’, Title page. Clara Dresel, ‘Little Clara's song – Clarchens lied’ Cincinnati: John Church & Co., 1877).

Ex. 1 ‘Little Clara's Song’, bars 1–9

Musically, this introduction proves a strange bedfellow to the vocal line, a lyrical and emotionally innocuous eight-bar tune. But the reason for the incongruity of the piano introduction and the vocal melody becomes clearer when we consider Otto's three verses of text (in both German and English). The melody gains an almost totally different valence when we learn that in these verses, Otto turned Clara's longing for her absent mother into mourning for a dead mother whom she hopes to meet again ‘in God's mansion above’. The singer is so grief-stricken at the loss of her mother that she wishes she had ‘died in [her] stead’. In light of this text, the foreboding piano introduction makes a great deal more sense. Although once published ‘Little Clara's Song’ did not remain entirely within the intimate home sphere, the work nonetheless powerfully underscores the emotional intensity of the family musical culture, the persistent undercurrents of lamentation and loss in the Dresel household, and Otto's own depressive tendencies.

***

We can easily imagine Otto, Louise, and their children playing and singing together in various combinations, filling their domestic cocoon with music. In all likelihood either Louise or Alma accompanied Otto while he played the violin; at other times Alma played while her mother sang. Mother and daughter almost certainly also played pieces for piano four-hands, several of which, as we noted, are included in Louise's collection. And it would be hard to picture this scene excluding either Herman or the younger daughters through most of the 1870s. In one sense these concerts reflected generational and gender differences typical of the time: father or son on the violin, mother and daughter singing or playing piano. On the other hand, binder's volumes known to have belonged to men are relatively rare, and Otto's involvement in this aspect of the female-dominated domestic realm was by most indications unusually strong. His love of music, along with his training and manifest talent, naturally made it likely that whatever family life he established would incorporate this interest. The same could be said of many, even most, German immigrants of his generation. If domestic music-making took on new importance as an emotional refuge for Americans in this period, the trend was owing not least to Forty-Eighters such as Dresel.

In their home environment, family members showed little interest in keeping up with contemporary musical fashions, either European or American. Instead they worked to develop personal canons that served their individual musical tastes and emotional needs.Footnote 77 Within the limits of their nearly exclusive German and European orientation, these volumes exhibit wide-ranging tastes, from opera to lieder, from instrumental fantasies on operatic arias to sonatas with no extra-musical referent. This variety helped nurture and enrich the Dresels’ home music-making, providing them with various and contrasting harmonic and stylistic moods. Even if the prevailing mood of their intimate interactions was one of nostalgic longing and melancholy, as I have argued, the breadth of their collections reflected their desire to embody the nineteenth-century ideal of domestic harmony through performing music together as a family.

Yet whatever harmony they managed to achieve was tragically fleeting. The domestic haven inevitably disintegrated in the wake of Otto's suicide, and its members lived far from happily ever after. Not long after his death, Louise fled abroad to Germany with two of her daughters (almost certainly Flora and Marie Louise), no doubt hoping that the land and culture so beloved of their husband and father might help fill the void his shocking exit had left in their lives.Footnote 78 Subsequent reports about the other children suggest that they never escaped the familial pall earlier reflected in their music but now immeasurably deepened by a dreadful loss. Alma simply vanishes from the available records after 1883, leaving no evidence of further connection with her home or family. Clara, despite her excellence as a student, bolted mysteriously for Europe even before her high school graduation; she would die in Denver, Colorado, aged only 32. Son Herman, who graduated with distinction from Annapolis and became a naval officer, would die by suicide in 1898, shooting himself in the head just as his father had done nearly 18 years earlier. According to newspaper reports he had been under treatment for ‘mental derangement’, and his self-destruction was attributed to ‘melancholia’; the likelihood of a congenital depression handed down from Otto seems difficult to dismiss.Footnote 79 Louise would sadly outlive all but two of her six children, returning to live in Washington, DC, only around 1909; she died four years later at the age of 77.Footnote 80

Whether by choice or by chance, at least some of the Dresel family sheet music volumes were preserved. As I hope to have shown, the music Otto, Louise, and Alma chose to have bound in their individualized volumes provides one window into their conscious or unconscious need for emotional release and personal consolation in intimate family music-making. Their private preferences and performances may well have exaggerated the darker, more extreme sides of the sentimentalism that pervaded this era. But especially in light of the enormous importance scholars ascribe to the overall role of German immigrants in shaping nineteenth-century American musical culture, the predilections of the Ohio Dresels can and should prompt questions about the distinctive functions of music in nineteenth-century American homes. Otto's public musical involvements reflected civic aims of brotherhood, national unity, and social uplift that were shared by many of his generation; in this respect he showed much in common with the Boston Dresel, whose fame and connections to luminaries in both Europe and the United States we noted early on. But like countless Americans who lived through the trials of the 1860s and the troubled years that followed, our Otto Dresel and his family had their share of reasons to mourn and to draw together for mutual comfort, and they did this not least by making their own more personal and emotional strains of musical expression integral to their domestic world.