Introduction

“The Global Rise of Populism,” as Moffitt (Reference Moffitt2016) titled his book, has captured immense scholarly and public attention throughout democratic societies and beyond. At the same time, an increasing number of studies note that right-wing parties achieving comparative success across Europe do “not easily match up with the classical attributes of right-wing extremism” (Bulli and Tronconi Reference Bulli, Tronconi, Mammone, Godin and Jenkins2012, 89). Populism, although renowned as a “politically contested concept” (Müller Reference Müller2017, 9), has generally come to the fore of studies examining the prominent political concerns about the crisis of the post-World War II liberal order. The “specter of populism,” which pioneering literature perceived to be “haunting Europe” (Ionescu and Gellner Reference Ionescu and Gellner1969, 2) some five decades ago, has today become a synecdoche used to describe different movements rooted in their own distinctive national contexts. While populists enthusiastically campaign against globalization processes, populism itself has been evolving as an increasingly globalized phenomenon. In addition to the resemblance between discourses, in 2016 Le Pen called Trump’s victory in the US a “global revolution” and “a victory of the will of the people over elites” (Finchelstein Reference Finchelstein2017, 158). On the periphery of Europe, in Georgia, the leader of the nascent social movementFootnote 1 Georgian March referred to the “awoken West” of Marine Le Pen, Heinz-Christian Strache, Viktor Orbán, and Donald Trump as their political inspiration and the “real West.” Some prominent scholars, such as Jens Rydgren (Reference Rydgren, Albertazzi and McDonnell2008) have even gone so far as to wonder why populist parties have not yet taken root in some countries, further indicating the pace of populism’s spread across democratic states.

Deploying a transnational approach, the article follows the explanatory framework of diffusion theories in aiming to provide a new perspective on the rise of national-populist actors across different sociopolitical and national-historical settings in the context of ever-increasing interdependence and transfers of ideas. In doing so, it capitalizes on the new modes, borrowings, and emulations to contribute towards a better understanding of non-institutionalized transnationalism. The wealth of scholarship addressing this area has so far overlooked the irreversible interconnection within the globalized world, where processes—including the emergence of similar political units—are informed by developments elsewhere. This study presumes that in such a context not only domestic structural and opportunity factors, but also the transnational diffusion of ideas and practices, should be taken into consideration in order to grasp the broader context of national developments. As such, similar populist actors, clustered around ideological outlooks, should be examined in interconnection. In this matter, European integration – in combination with the increasing role of new media communication platforms – acquires particular analytical importance in relation to the cross-national diffusion. Against such background, I argue, the new modes of borrowing contribute to a transnational form of locally (nationally) emerging national-populist discourses, even when the apparent forms of direct collaboration and institutional cooperation are scarce. Moreover, the study spotlights the relevance of “mediated” politics and discourses vis-à-vis the traditionally appropriated spatial and temporal proximities with regard to forming transnational linkages.

For demonstrating the theoretical claims about diffusing ideas and transnational modes of borrowing, I intend to examine the evolution of national-populist discourses in post-communist Georgia. The idea of a “crossroad” (between West and East; Christianity and Islam) has been deeply embedded into the country’s internal understanding of its own position on the global and regional map. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the beginning of transition processes, the small independent state of Georgia became particularly exposed to international politics, especially due to its attempts to counterbalance Russian “near abroad” politics on the one hand and Georgia’s intention towards integration with European and Euro-Atlantic structures, on the other. Thus, this case, located within two contexts – post-Soviet legacies and involvement in Europeanization Footnote 2 – provides the relevant modes of transnationalism for the perspective and aims of this article. In a broader sense, the case illustrates, on the one hand, the vulnerability of trasitioning democracy against national-populism and, on the other, the susceptibility of democratic and pro-Western ideas against devious interpretations in the country.

With the intention to contribute to this comparatively disregarded research track,Footnote 3 this article focuses on understanding the spread and adaptation of national-populism across different socioeconomic, geographic, and cultural settings by examining the case of a national-populist social movement: Georgian March. For this analytical purpose, it adopts the theoretical and methodological frameworks from social movement studies together with diffusion theories and combines them with methodological tools from historical-discourse analysis (HDA). It therefore explains how the “success” of national-populist politics elsewhere can influence similar units in socio-culturally different places and how the adaptation of exclusionary discourses is taking place. The theoretical argument and the case reveal yet another paradox of national-populism: whereas it constructs anti-globalization as well as anti-transnationalization narratives in the center of its master discourse, it is quietly evolving as an increasingly transnational and global phenomenon itself.

The Georgian case constitutes one example of the emergence of national-populist groups following the rise of exclusionary populist ideologies throughout the “Western liberal democracies.” The electoral rise of national-populist powers in states such as Hungary and Poland became a point of positive reference and of a true “Europeanness” for their Georgian counterparts, while Europe’s liberal values remained as targets of demoralization and negative references for them. Vis-à-vis the official political discourses establishing the state’s external course around the notion of “going back to European roots,” the emerging national-populist actors use references to the West or to their version of “Europe” in an attempt to legitimize exclusionary, racist, homophobic, or xenophobic rhetoric, along with adopting discursive frames and strategies from European national-populist actors. The analysis identifies and focuses on the instances where Europe is used in two different ways: as a reference point for exemplary models, as well as for constructing the fear of possible negative scenarios.

The selected case of Georgian March is embedded in the particular national context of Georgia and provides interesting implications for the research domain for several important reasons. First, it scrutinizes the interplay of strong and enduring European and EU political aspirations of a marginal Eastern European country and the rising national-populist discourses there. Second, it explores and provides a model for incorporating a post-Soviet Eastern European country’s example into the broader historiography of the European region and that of post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Third, it locates a remote case within an important historical and political process and depicts the possible frames in which entanglements occur. Fourth, and most importantly, it provides a new dimension to the study of exclusionary politics in which pro-European (and pro-Western) arguments can become an integrated part of the discourse in particular contexts without changing the nationalist-populist character of an actor. And finally, this case provides a theoretical merit for incorporating the factor of external legitimization in comprehending the broadly discussed emergence of national-populism. Discursive strategies and tactical framings will be thus incorporated among the key elements of the analysis.

The Working Concepts: Populism, Nationalism, and National-Populism

Eastern and Central European cases in post-Socialist context have been classified within the ethnic type of nationalism informed by legacies of communist rule (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2009; Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996). At the same time, populism came to be an inevitable perspective in studying the contemporary, allegedly transformed, right-wing in Europe (Tarchi Reference Tarchi, Albertazzi and McDonnell2008). For these reasons, I propose to deploy the concept of national-populism as a guiding “category of analysis” (Brubaker and Cooper Reference Brubaker and Cooper2000). When analyzing national-populism, however, it is important not to take this analytical category for granted as the concept is rather contested. In their recent work, De Cleen, Glynos, and Mondon (Reference Benjamin, Glynos and Mondon2018) have convincingly proposed the need for caution when considering “the architecture of populist politics” and the essential prerequisite of clarifying whether populism, or some other ideological element, constitutes the core of the unit under scrutiny (6). Moreover, identifying the centrality of discursive elements throughout the political rhetoric is considered to be an important step in identifying and assessing discourses commonly referred to as “populist.” At the same time, among others, Rydgren (Reference Rydgren2017) notes that populism is not an essential, but conditional qualifier of such actors emerging from other central ideological roots (nationalism, social-democracy, etc.).

All things considered, I refer to national-populism where the nodal points of populism (the people/the elite) are combined with Meinecke’s (Reference Meinecke1908) Kulturnation. Footnote 4 In these terms, I attempt to avoid the broadly criticized and mostly normatively bargained classification between Kohnian civic and ethnic types and consider the idea of “cultural unity” to be embedded in divergent types of nationalism.Footnote 5 Nationalism itself is therefore considered from a constructivist perspective and seen as an instrumental “discourse that constructs the nation” along a horizontal in/out exclusion of “national members” (De Cleen and Stavrakakis Reference Benjamin and Stavrakakis2017, 8). The cultural nationalism and differential racism generally appear at the center of the national-populist discourses, ostensibly influenced by New Right intellectual thought (Leerssen Reference Leerssen2006). As for the “minimal concept” of populism, it is defined “…as a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic camps, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (Mudde Reference Mudde2004, 543). The category of national-populism is helpful for implying a combination of analytical elements (nationalism and populism) in the ideological core of those commonly referred to as populist actors, especially in (Central and Eastern) European contexts.

The concept of national-populism has been deployed in several contexts, beginning with Germani’s (Reference Germani1978) work on populism in South America and continued by Taguieff’s (Reference Taguieff1995) notion of exclusionary “new populism.” Considering the exclusivist nature of the mentioned discourses, I follow the later conceptualization adopted and modified by Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2017). Thus, national-populism is defined by confronting polarization between “us” and “them.” Brubaker underlines the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the polarization offered by Taguieff (Reference Taguieff1995). In the former, national-populists tend to claim representation of “the ordinary people” vis-à-vis “elites,” both the categories being discursively constructed. As for the horizontal extent, a clash is perceived to be happening between “people like us” sharing and praising our way of life and “outsiders” – not only outside of the “national borders,” but also those who might be living among us, but pose a threat to our culture, customs, and lifestyle. Thus, “power back to the people” conveys an all-changing embedded element: “only some of the people are really the people” (Müller Reference Müller2017, 21). Specific segments of the population are stigmatized and excluded from “the people” as a threat to and a burden on society (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007, 324).

Intersecting National-Populism and Diffusion Theories

Populism (in all its manifestations) has garnered immense academic as well as journalistic attention throughout the last decade, but the processes of mutual reinforcement and legitimization among populist actors, as well as practices of learning from each other via non-institutional and informal channels, have mostly been left for journalistic ad hoc speculation rather than subjected to systematical analysis. Nationalism in this sense demonstrates a longer academic tradition, its transnational spread having received rather more systematic attention, especially in the context of instrumentalist theories of nationalism (Greenfeld Reference Greenfeld1992). Nevertheless, scholars have been highlighting similarities by clustering populist actors alongside the ideological outlooks and/or geographical spaces according to common repertoires and discursive strategies. In these terms, Rogers Brubaker analyzed repertoires of national-populists in Europe and the US using the “family resemblance” approach (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017).

This approach of clustering populist cases in space and time indeed proves essential for understanding historical patterns of populism, but also opens up new, yet scarcely explored, paths to approaching such actors not as discrete but as principally entangled formations. This academic lacuna is especially pressing in reference to right-wing national populist cases. In fact – following Caiani (Reference Caiani and Jens2018) – while “left-wing internationalization” has long been studied by scholars such as Della Porta and Kriesi (Reference Della Porta, Kriesi, Porta, Kriesi and Rucht1999) or Strang and Meyer (Reference Strang and Meyer1993), the same approach has rarely, if ever, been applied to right-wing actors in a European context. Referring back to the case, even though the latest appearance of national-populist discourses in Georgia are largely discussed in connection to “other European cases,” the process is perceived as developing concomitantly yet examined through a profoundly domestic context.Footnote 6 This study attempts to contribute to the field precisely by rethinking such a perspective on the evolution of national-populism in this part of Europe.

The respective literature has looked thoroughly at institutional ties and formal allies of (national) populist leaders at the EU level, although this perspective leaves room for issues such as informal borrowings of discourses/policies through indirect channels and mutual legitimization strategies at the non-institutional level. Among other scholars, Minkenberg and Perrineau demonstrate a skepticism about the plausibility of an “international group of nationalists” (in Brack and Startin Reference Brack and Startin2016). Yet, the scholarly contributions of the last two decades that have sought to explain patterns and means of cooperation among radical right actors at the EU level draw two types of conclusions. One refers to the initially strategic, and therefore short-lived, purpose of the cooperation and underlining that the “primacy of nationalisms [within these parties] undermine any potential for ideological alliances” (Vasilopoulou Reference Vasilopoulou and Rydgren2018). The second highlights the combination of pragmatic reasons and shared ideological convictions (Brack and Startin Reference Brack and Startin2016). Hence, the prior scholarship on this matter converges around the idea that the nationalist nature of these actors, the prominent factor of a charismatic and somewhat impulsive persona within these groups, along with the cordon sanitaire of the EU and, arguably, that of the traditional media, are believed to be the preventive factors for creating such a cooperation. Both the mentioned analyses follow and analyze the timeline of formal ties. While the methodology provides a valuable frame for comprehending the limits and potential of right-wing internationalization, I, however, submit that this perspective leaves room for emerging questions about discursive convergence and mutual positive references even when the forms of formal cooperation are scarce or non-existent.

Integrating the logic of a transnational approach, I suggest focusing on mediated experiences as providing models for certain behaviors; new roles and uses of social media, as direct political platforms and channels for diffusions and borrowings; the factor of mutual references as tools for self-legitimization and mutual identification; and the relevance of borrowings among national-populist actors. As partially demonstrated above, thus far, non-institutional transfers of ideas and the mechanisms of diffusing ideas/practices, along with grounds for mutual positive references across populist movements, have received little academic attention.Footnote 7

Diffusion Theory and Methodological Tools

Building on the study of McAdam and Rucht (Reference McAdam and Rucht1993), as well as the conceptual frameworks of Wejnert (Reference Wejnert2002) and Ambrosio (Reference Ambrosio2010), I adopt theories explaining the diffusion of innovations, of authoritarian regimes, and of social movements in the modern context. One of the classic conceptualizations broadly defines diffusion as “any process where prior adoption of a trait or practice in a population alters the probability of adoption for remaining non-adopters” (Strang Reference Strang1991, 325). In particular relation to social movements, Della Porta and Kriesi (Reference Della Porta, Kriesi, Porta, Kriesi and Rucht1999), and Soule et al. (Reference Givan, Roberts and Soule2010) demonstrate how themes, frames, action repertoires, and strategies are diffused cross-nationally. The frames are interpretative and include the way actors articulate and codify issues, problems, and their solutions, and target outsiders to mobilize political claims (Givan et al. Reference Givan, Roberts and Soule2010). Conceptually, diffusion of innovations is related to dissemination of “abstract ideas and concepts, technical information, and actual practices within a social system, where the spread denotes flow or movement from a source to an adopter, typically via communication and influence” (Wejnert Reference Wejnert2002, 297). Diffusion is therefore a process, rather than the outcome, delineating the relevance of interdependences in policy choices (Elkins and Simmons Reference Elkins and Simmons2005). Diffusion has been an extensively researched area throughout different fields of social sciences, communications, and economics. This paper integrates the theoretical framework from diffusion studies and social movements into studying the resurgence of right wing national-populist discourses against the background of non-institutionalized cooperation.

Studies on diffusion from these diverse research domains are primarily concerned with questions related to its actual occurrence as opposed to global trends or regional clustering of local developments on the one hand (Brinks and Coppedge Reference Brinks and Coppedge2006, 464), and the possible explanations for it, on the other (Ambrosio Reference Ambrosio2010). McAdam and Rucht (Reference McAdam and Rucht1993), among others, describe conditions where diffusion is likely to happen and define three dimensions to be established for marking the processes of diffusion, which I adopt for scrutinizing the case. In terms of the conditions, hierarchical and proximity models are highlighted: the former stands for adopting ideas and practices from advanced units whose strategies have proven successful. In this case, “the more important unit is taken as the reference group by the less important units in the set” (Della Porta and Kriesi Reference Della Porta, Kriesi, Porta, Kriesi and Rucht1999, 7). The hierarchical model is in line with the broader category of appropriateness that explains adoption through diffusion via (perceived) legitimacy of certain norms and practices within the regional or global context (Elkins and Simmons Reference Elkins and Simmons2005). Hence, changes in perceptions of legitimacy and appropriateness of certain ideas, norms, or even regimes, affect the process and nature of diffusion (Ambrosio Reference Ambrosio2010). Moreover, the construction of similarities with more “advanced” cases serves to create legitimacy for political claims and protest strategies. Effectiveness is another broader mechanism of diffusion that takes into consideration actors’ judgement of external experiences in relation to the prospective norms or policies to be adopted. The above-mentioned mechanisms are not alienated since the actors often perceive practices as successful based on their biases about an emitter’s advanced position (Ambrosio Reference Ambrosio2010). In this regard, the international prestige of an actor, as stated by Fordham and Asal (Reference Fordham and Asal2007), might play a decisive role in setting appropriate models, channeling diffusion, as well as in providing grounds for legitimizing adoption of practices and values on the local level with an aim or justification of international compliance.

Together with appropriateness, effectiveness, and international prestige, factors such as spatial and cultural proximities, economic ties, or organizational linkages are outlined among the accelerators for establishing links and adopting practices (McAdam and Rucht Reference McAdam and Rucht1993; Ambrosio Reference Ambrosio2010). Geographical proximity – exposing actors to the external experiences of nearby cases –mostly acts as an accelerating factor for enhancing other mechanisms rather than an independent trigger itself (Börzel and Risse Reference Börzel and Risse2012). Furthermore, as Sedaitis and Butterfield (Reference Sedaitis and Butterfield1991) observed with the example of social movements in the Soviet Union, the political situation is pivotal in the process of adopting ideas for transformation. Likewise, the previous experience of interactions and borrowings with the same source positively affect the adaptation process (Wejnert Reference Wejnert2002). Nearly all the authors mentioned here, outline direct and indirect influences among mechanisms of diffusion. Normative (“mimicry”) and functional (“competition/lesson-drawing”) emulation is at the center of analysis regarding the indirect mechanisms of diffusion, where the adopters look for the “best practices” elsewhere for proposing local changes (Börzel and Risse Reference Börzel and Risse2012, 14).

Above all, an initial stage of diffusion is established through minimal identification of an emitter with an adopter where framing of a (symbolic) analogical situation occurs. Minimal identification is related to institutional equivalence referring to the corresponding institutional characteristics such as society, state system, or socio-historical background that dictate adoption of alike practices (Strang and Meyer Reference Strang and Meyer1993). In constructing homogeneity with the source, the collective actors perceive structural equivalence through different factors varying from economic to strategic and behavioral (Wejnert Reference Wejnert2002, 308). Here an “adopter” is an active interpreter/“translator,” who constructs, articulates, and frames imported ideas according to contextual mores (Della Porta and Kriesi Reference Della Porta, Kriesi, Porta, Kriesi and Rucht1999, 7). Börzel and Risse (Reference Börzel and Risse2012, 5) connect the logic of social action to diffusion mechanisms, where logic of consequences, logic of appropriateness, and logic of arguing come to the fore. The distinction among these logics is analytical: the three often come in combination in a single action, since the actors aim at maximizing their gains and being included in a particular community (regional/international) for which they often use persuasion and legitimization. For this case study too, diffusion is not a passive process of spreading; instead, Georgian March interprets as appropriate and effective – and strategically adopts – discursive topics, political and discursive strategies, language, etc. As far as methodological tools are concerned, the theory underlines three dimensions used to mark the diffusion. I address each dimension, which involves deploying a triangulation of methods.

-

1. Temporal sequence: meaning that the temporal course of collective action between an adapter and transmitter are consistent. For this study, I systematically analyze the emergence, borrowing, and adoption of discourse topics by Georgian March within the broader context of right-wing populists’ success and discourses developed elsewhere.

-

2. Apparent borrowing of core elements: similarities in identity components and problem-definition components. For the former, identifying with counterparts is in line with the construction of the group’s collective identity. This process includes justification of using transmitter models for one’s own actions. Similarly, the problem-definition component relates to the adaptation of the frames for defining issues. Borrowed and modified items might include protest forms, slogans, general repertoire, and – importantly for national-populism – appeals to democracy. In contrast to other processes evolving a degree of mimetic isomorphism and spreading of discourses or policies, in this case of indirect diffusion any real or structured collaboration, as well as programmatic effort, is neither required nor necessarily instrumental (Elkins and Simmons Reference Elkins and Simmons2005). In order to demonstrate and explain the reasons of adaptation, historical discourse analysis, providing a basis to observe and explain the recontextualization of discourses in Wodak’s (Reference Wodak, de Cillia, Reisigl and Liebhart2009) terms, is applicable.

As for the specific analytical tools in this dimension, I turn to the Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) method within the historical-discursive approach (HDA), developed by Wodak and Reisigl (Reference Wodak and Reisigl2001).Footnote 8 Consequently, not only a conceptual meaning of the text is taken into consideration, but also the way it is adjusted to domestic cultural and historical contexts that helps to explain the interpretations of the adopter. I suggest that the adaptation occurs in the context of construction of the self (and “the other”) involving the strategies of legitimization. The approach is relevant for the study as it assists in systematically analyzing the argument schemes Footnote 9 suggested by Wodak and Boukala (Reference Wodak and Salomi2015).

-

3. Means and channels of diffusion: Identifying the means of diffusion is equally important. Here the role of technological modernization comes to the fore, even surpassing the factor of spatial proximity, furthering the multidimensional role of both traditional and new media for communication. The media serves as a platform for mutual references, framing issues, and constructing discourses related to both domestic and international developments. For this case, an indirect learning process and strategic framing of issues happening elsewhere are central points of analysis. I propose that media also offers a platform for diffusing visual elements and other non-verbal forms of expression cross-nationally. According to Moffitt (Reference Moffitt2015), the media, together with a crisis, provide a stage for populist leaders’ performances. Besides illustrating the new platform of communication offered by mass media or, as Mazzoleni and Bracciale (Reference Mazzoleni and Bracciale2018, 3) call it, “new media logic” – the role of network media in shaping and articulating the success of populists across Europe is noteworthy.Footnote 10 From the point of diffusions of innovations, media is of paramount importance for several factors, including: disseminating information; bringing loosely connected actors in a network together; promoting the “emitter;” providing a platform for a non-relational communications; and initiating a discussion on the innovation to be borrowed.

As generally observed in the field of social movement studies (e.g. Dolata Reference Dolata2017), network media infrastructure were essential also for the early and the most active period of the movement under scrutiny in this paper: it had been deploying the social media platform to construct its collective identity and exclusionary discourses, legitimizing them on a daily basis and reaching out to mass society. Consequently, Facebook has acquired a comparatively novel function as a mobilizing “stage” for Georgian March. At the same time, as discussed above, social media plays an immense role as a channel of diffusing discourses and practices. Hence, posts on the movement’s official Facebook page and that of its leader are used among the materials of analysis.Footnote 11 Since the Facebook data are from time to time subjected to the tech company’s content-related restrictions and might pose a challenge for further replicability,Footnote 12 I supplement the quantitative data from Facebook with semi-structured interviews conducted by myself with the movement’s leader and several active members.Footnote 13 The interviews are coded and analyzed qualitatively, using the software tool ATLAS.ti and submitted to CDA. The social media data (952 posts)Footnote 14 and secondary materials, including online published interviews with GM leaders, are filtered according to two criteria: 1) temporal – data published in close proximity to the protest events throughout the first year of GM’s appearance; and 2) thematic – explicitly or implicitly related to the subject of an event and referring to “Europe/US/Occident” at the same time.

This article thus situates the emergence of national-populism in Georgia into the “global rise of populism,” and illuminates the adaptation of discourses and framing of events happening “in the West” by Georgian March. When analyzing conflicting discourses, the issues of argumentation and persuasion come to the fore, both serving to legitimize political statements and decisions vis-à-vis the social interest and public will (Mişcoiu, Crăciun, and Colopelnic Reference Mişcoiu, Crăciun and Colopelnic2008, 36). While legitimization is an inseparable part of political discourses in general, it acquires special importance for oppositional national-populist actors as it is essential to their securitizing narrative. Hence, analytically, references to “the West” ought to be approached within the framework of discursive legitimization strategies. According to Eatwell (Reference Eatwell2006), one of the most important aspects in terms of the durability and electoral emergence of the European radical right is acquired legitimization, which is particularly important for radical actors to overcome historical demonization. The three-stage methodological framework serves as an analytical track for marking the diffusion of national-populist discourses. The main tool for demonstrating not merely the fact of diffusion, but also the circumstances under which it takes place, lies in illustrating the discursive construction of a “double Europe” by the movement.

Introduction to the Georgian Case

Since the 2016 parliamentary elections in Georgia, when the Alliance of Patriots – a right-wing conservative party – managed to win six seats in parliament, the “populist Zeitgeist” (Mudde Reference Mudde2004), perhaps in a national-populist form, has been revealing itself in the Georgian sociopolitical arena too.Footnote 15 Against this backdrop, the social movement under the name “Georgian March” paraded down the avenue named after the monarch David the Builder in July 2017, chanting anti-immigrant and national-populist slogans. Since then, the movement has established itself mainly around the discursive fields of immigration, elite corruption, anti-establishment sentiment, anti-foreign influence, national identity, and family values, together with anti-LGBTQ rhetoric, anti-multiculturalism, and anti-liberalism. Even though they have not achieved an electoral success yet,Footnote 16 the movement remains on the political scene and has transformed into a political party. Moreover, the emergence of this umbrella movement has certainly influenced the rise of national-populism in Georgia and reflected the vulnerability of contemporary democracies against such political discourses. As Wodak (Reference Wodak2015) notes, mainstream parties typically take over the popular policy proposals of these groups in order to prevent their political success. She calls this process the “normalization of right wing populist policies” (Wodak Reference Wodak2015, 184), of which Georgian March is a frontrunner in contemporary Georgia.

Since its emergence in 2017, Georgian March (afterwards GM) has managed not only to influence some political decisions in the country, but more importantly to shape the landscape of “nationalist” [erovnuli] power and propose issues for public discussions over normative matters that, most of the time, lead to public polarization. GM, since its inception, combined different far right and conservative units not particularly represented in either political or public arenas before. It also includes the organization Nationals [Erovnulebi] led by Sandro Bregadze, perhaps the most enthusiastic initiator and self-proclaimed leader of GM. Bregadze and his team, who became organizers and members of GM, proposed constitutional amendments in the name of the “Georgian people”Footnote 17 and collected citizens’ signatures to have an impact on political decisions. Their political influence was revealed in the amendment to Article 30 on “Rights to Marriage,” included in the constitutional decision of May 3, 2017, which specifies marriage as a union of man and woman (“Constitution of Georgia” 1995, Ch. 30). It is noteworthy that a similar amendment was applied to the Hungarian constitution enacted by the government of the prominent national-populist leader, Viktor Orbán (Hungary’s Constitution 2011). As discussed below, the Hungarian government is one of the most frequent reference points for the movement in their quest for legitimacy. As for the other proposed amendment initiated by GM concerning complete and unconditional prohibition on the sale of Georgian land to foreign citizens, the parliament did not confirm a complete prohibition, but specified a need for the land for sale to have a “special status” ( “Constitution of Georgia,” Ch. 19). Once again, this complies with the picture described by Wodak, where “almost the entire political spectrum moves to the right” (Wodak Reference Wodak2015, 184).

The national-populist discourses of Georgian March are different from traditional right-wing rhetoric in the country in that they comply with the dominant political discourse linking the West with progress, but in these terms, the “new version” of the “real” West is created and presented through Orbán, Le Pen, Trump, or Strache. They are portrayed as “good” and “exemplary” within the Manichean rhetoric of the movement. Explaining the process of diffusion through examining this double construction is one of the aims of this study. For GM, I suggest, this type of progressive West, “protecting its culture and national identity against liberalism, multiculturalism and foreign influence,”Footnote 18 becomes a tool for legitimizing exclusionary populist discourses at the local level. In these terms, the diffusion and borrowing of national-populism is definitely about a common “other.” However, it goes beyond this and implies a similar set of logic, master frames, discursive strategies, and sometimes even content. Nonetheless, it should be emphasized that the adaptation process involves modification and adjustment to local standards. Moreover, even though the movement’s name, as well as some of its political demands (for instance, the prohibition on financing NGOs – “foreign agents” – from abroad), also resemble Russian discourses of recent years, Georgian March avoids referring to the practices of the country’s northern neighbor, which is explained by the negative normative connotation that Russia carries within public discussions in Georgia. Although the leaders of GM have announced the movement to be “pro-Georgian,” in contrast to “pro-Russian” or “pro-European,” ambivalent references to “the West” have been an accompanying part of their discourses.

Within the discourses of Georgian March, horizontal boundaries are constructed around the “Georgian nation” [Eri], while the vertical dimension excludes the corrupted governing elite, which, according to the movement, is collaborating with foreign liberal influencers. Therefore, while it is included into the “national boundaries,” the elite (political, cultural, NGOs) is constructed and denounced through the populist dimension of the movement’s national-populist discourse. It is noteworthy that in contrast with the some of the prominent Georgian nationalists of the 1990s – represented as inspirational idols by the GM members – the “Georgian nation” includes ethnic minorities, at least in the frontstage discourses of Georgian March.Footnote 19 In the movement’s discourse, mixed use of traditional and modern prejudicesFootnote 20 results in the following excluded categories: “illegal immigrants” (mainly Arab and Indian nationals), liberasts (a pejorative term combining “homosexual male” and a liberal person in Georgian) and vague labels, such as “traitors.”

The Notion of the Occident in General Socio-Historical Context

Before moving on to empirical analysis, it is important to outline the context of connotations of the Occident in order to better understand the logic behind the double construction of the West, as well as clarifying the use of emulations and positive references as tactics for self-legitimization. The West, Europe, or the Occident are interchangeably used throughout the study insofar as, following Nodia (Reference Nodia, Coppieters, Zverev and Trenin1998), Georgian public perception has historically held a symbolic meaning of Europe and the US without precisely distinguishing between “European” or “American” within the prism of “the Occident.” However, in the context of EU integration processes, the elite political discourses in Georgia since the Rose Revolution of 2003 have contributed to the creation of new “European” discourses. This, in conjunction with stable high levels of public support towards the EU and intensified informational projects within the Eastern Partnership program, have resulted in bringing Europe to the center of the Occident in Georgian popular perception. EU integration is perceived as rather a political consensus in the country and the issue of Europeanization serves as a political battlefield for constructing one’s identity via drawing lines with “outsiders.”

At the same time, historically speaking, the “Western orientation” of Georgian national consciousness has been consistently attended, and sometimes even informed, by uncertain attitudes towards Russia (Sabanadze Reference Sabanadze2013). Even the founders of the first Georgian nationalist project in the late 1800s perceived Western civilization, at the time, to be only accessible for Georgians through Russia (Nodia Reference Nodia, Coppieters, Zverev and Trenin1998). Alongside temporal and geopolitical changes, this belief transformed into perceiving the West and Russia as two opposing poles informing the political course of Georgia. As research reports on anti-Western attitudes by the Media Development Foundation (MDF “Anti-Western Propaganda, Reference Kintsurashvili2016”) show, in contrast to the late nineteenth century, Russia is not seen as a route to “European civilization” but rather an alternative to it. Nowadays, this attitude is revealed in elite discourses, where rhetoric recommends a “return to historical roots—to Europe.” This can be seen in a speech delivered by the ex-prime minister at the Independence Day celebrations: “Georgia has returned to its European roots, and this is where we intend to stay” (Kvirikashvili Reference Kvirikashvili2016). This speech resembles one by former president Saakashvili several years ago: “This is not, of course, a new path for Georgia, but rather a return to our European home and our European vocation, which is so deeply enshrined in our national identity and history”(Saakashvili Reference Saakashvili2013). Within these “pro-Europeanization” discourses, the issues started to be comprehended in the context of “a progressive route” (towards the West) versus “regression,” related to a propensity toward Russian imperialism. At the same time, active references to “progressive changes,” which over time became linked to the West, have provided a direct source for conservative powers to associate “imposition of values” and threats to national and cultural identity with “the West.” Fitting the same narrative but filling it with different meaning, the leaders of GM attempt at recontextualizing it and advocate for a European path where “Europe is diversity and Europe is going back to the nation-states and national ideologies…” (Nemsadze Reference Nemsadze2019, interview).

The aforementioned research by the MDF indicates that anti-Western attitudes in media are mainly (32.7%) “concerned with issues of identity, human rights, and values.” The dominant view within such media over the past years has been that the West tries to impose “homosexuality, incest, pedophilia, zoophilia, perversion, and struggles against national identity, traditions, Orthodox Christianity, and the family as a social institution” (Kintsurashvili Reference Kintsurashvili2017). Anti-Western discourse is stably dominated by issues and fears related to identity, among which the fears over unacceptable values, threats to traditions and the Christian Orthodox Church, and the imposition of homosexuality and immorality are prevalent (Kintsurashvili and Gelava Reference Kintsurashvili and Gelava2019). Other anti-Western tendencies revealed in media resemble the issues that Georgian March is trying to securitize. The most obvious examples of this are the following: the prohibition of foreign finances to NGOs (which work for “foreign interests” in Georgia); the association of the EU and the visa waiver regime with the obligation to receive immigrants (therefore “increasing the threat of terrorism”); and skepticism towards EU/NATO-Georgia relations.

However, the discourses of Georgian March differ from traditional anti-globalist and anti-Western sentiments by persistently referring positively to Western examples. At the same time, it constructs its own vision of the West, thereby maintaining and subtly endorsing traditional anti-Western discourses. Hence, it denotes a paradox that Georgian national-populists, via reinterpreting Europe itself, selectively borrow from the European far-right, simultaneously endorsing the opposition to traditional pro-European politics as pursued in the country. It also demonstrates how, against the transnationalization and diffusing path, the localization of external ideas (Acharya Reference Acharya2003) is occurring via vernacular idioms and the dominant political sentiments in the country. I conclude that this type of “progressive West” becomes a tool for legitimizing prejudiced and discriminatory language, while upholding anti-Western attitudes. In their discourses, Europe (in its positive association) is conservative and “classic:” “Europe is, of course, a continent of conservative, traditional values” where integration is acceptable only if “everyone’s traditions, identity, and way of development will be maintained” (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2019, interview).

Mapping the Discursive Fields of Georgian March

Following the timeline of the events organized by GM during the first year of its existence and the interview analysis, this article locates three main discursive fields and respective topics deployed by the movement. Alongside anti-immigration discourse – which, in this form, is a novel matter in Georgian nationalism and the foremost mobilizing issue for Georgian March – the movement also constructs discourses related to Christian and family values, while railing against “foreign liberal influence.” Within each of these discourse fields the movement’s leaders, as well as its official Facebook page, constantly refer to the “Western examples” and “success stories” of European and North American national-populists in the context of self-legitimatizing and mobilizing rhetoric.

In order to demonstrate borrowing through diffusion and explain the process, I firstly create a timeline of the actions (protests, marches, announcements) of the movement in its emerging phase, starting from the first organized march in July 2017 until March 2018. The qualitative analysis of the emerging phase is selected insofar as the period proved the most important for the movement to establish and legitimatize itself, when mutual identification and external references were central to the actor’s discourse and collective identity construction. Secondly, I analyze discursive fields and strategies in depth, focusing on the incorporation of “the West” in it. Figure 1 describes the activities of Georgian March on the temporal continuum.

Figure 1. Timeline of Actions by Georgian March

The first public appearance of Georgian March was related to securitization of the immigration issue, which, in this form, had never been part of nationalist discourses in Georgia. However, mobilization of anti-immigrant grievances around security issues proved successful as a considerable number of people gathered on the avenue named after David the Builder (the historically celebrated monarch from Georgia’s “Golden Years” of the twelfth century). Many bars and restaurants owned by people of Turkish or Arab origin have been situated on this avenue for several years now, but immigration became an issue of wider public discussion simultaneously with the appearance of GM and their organized protest movement.

The anti-immigration discourses are important not only for analyzing construction and legitimization strategies in reference to anti-immigrant rhetoric, but also for comprehending discourses concerning the emergence of the movement. Two weeks before the protest, the leader of the movement took to Facebook to draw parallels between his group and the French Front National, which he claimed constituted an immutable necessity against liberals and globalists in Europe. According to him, the need to create a “Georgian Front National” was critical in Georgia today.Footnote 21 Sandro Bregadze attempted to legitimize the announcement of the new power, promising that it would replace the “stinking system” and create the foundations for a “national, just, and equality-based” state. In this way, references to the West have occupied a considerable part of the movement’s discourses even in its early stages of collective activity.

The following event addressed a demand to ban selling Georgian lands to foreigners. Georgian March representatives accused “Georgian Dream” – the governing coalition – of betraying Georgian people by maintaining the conditional rights of foreigners to buy Georgian land. The issue was framed within anti-immigration discourses and involved topics such as demographic change and territorial integrity (within such discourses, selling the lands merely constituted “another occupation”). Notably, the leader emphasized Russian occupation within these discourses in a dual attempt to equalize the importance of these two issues and avoid affiliation with the Russian government (which has been part of public discussions since GM’s appearance).Footnote 22 Referring back to the demand, Bregadze touched on European practices and legitimized the protest in such terms: “….also based on European experiences, because that is how it is in many European states, we prohibited selling agricultural lands to foreigners” (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2019, interview).

The next important appearance of the movement was related to a protest against the Open Society Foundation (OSF) branch in Tbilisi. During the same day, the protesters moved to the nearby office of the governmental representative, a mayoral candidate, to hold a protest meeting against them allegedly lying to the Georgian people. The logic of conducting these two protests simultaneously was revealed in their speeches, and later internet posts, labeling the governing elite as “Soros slaves” who operated against Georgia in favor of foreign interests. Soros has been accused of intervening in internal affairs, arranging the Rose Revolution in 2003,Footnote 23 and managing media that, according to the movement, “promotes homosexuals, encourages blasphemy and all manner of vileness” (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2017a). In a broader sense, this discourse addresses the strong belief of the Georgian public in the existence of non-formal governance and associated dissatisfaction (Vacharadze Reference Vacharadze2017).

Besides the matter of domestic dissatisfaction, GM’s Facebook page and its leaders continuously referred to Europe in their mobilizing appeals. Much like the anti-immigration sentiments, the expression “Europe is awakening” was actively used before the anti-Soros and anti-OSF protests (see Figure 3) in attempts to demonstrate “what is appropriate.” These discourses also included stories related to the “closure” of Central European University (CEU). One of these posts showed the protest in support of CEU, but was portrayed in the opposite way (see Figure 2, depicting Russian TV channel on the post).Footnote 24 Thus, in addition to framing events happening elsewhere, sharing unverified and objectively inaccurate information through Facebook is also an integral element of the movement’s discursive strategies.

Figure 2. Screenshot 1 “Europe has awoken, we should as well!!!”

Text(2): “There were public protest movements in Hungary and Macedonia against George Soros, which resulted in breaking into the Soros foundation in Macedonia!!!”

Figure 3. Screenshot 2 “Europe against Soros”Footnote 25

Text (3-first paragraph): “Attention!!!Europe expelled the Soros foundation with the accusation of violating its sovereignty.”

Homophobic sentiments had previously been part of anti-Soros and anti-“foreign influence” discourses, but were intensified in the response to a decision by Guram Kashia, the captain of the national football team, to wear a colorful armband in support of LGBT rights. After this game for his club in the Netherlands, Georgian March did not delay its backlash (Cole Reference Cole2020). Mobilizing resentments over perceived threats to family values and “homosexual propaganda” intensified, both on the movement’s official Facebook page and in Bregadze’s personal interviews with different online media outlets. In addition to using phrases such as “liberal dictatorship” and “threat to Christian values,” the leader framed this issue interdiscursively in the context of demographic problems, “imposed regulations,” and “Soros agents.” In these terms, the slogan “homosexual propaganda” is ascribed to the Georgian media, which, according to the movement, is mandated by Soros (See Figure 4, text under the picture: “The best tool to influence mass ideology is Television”).Footnote 26

Figure 4. Screenshot 3: Soros and Georgian Media

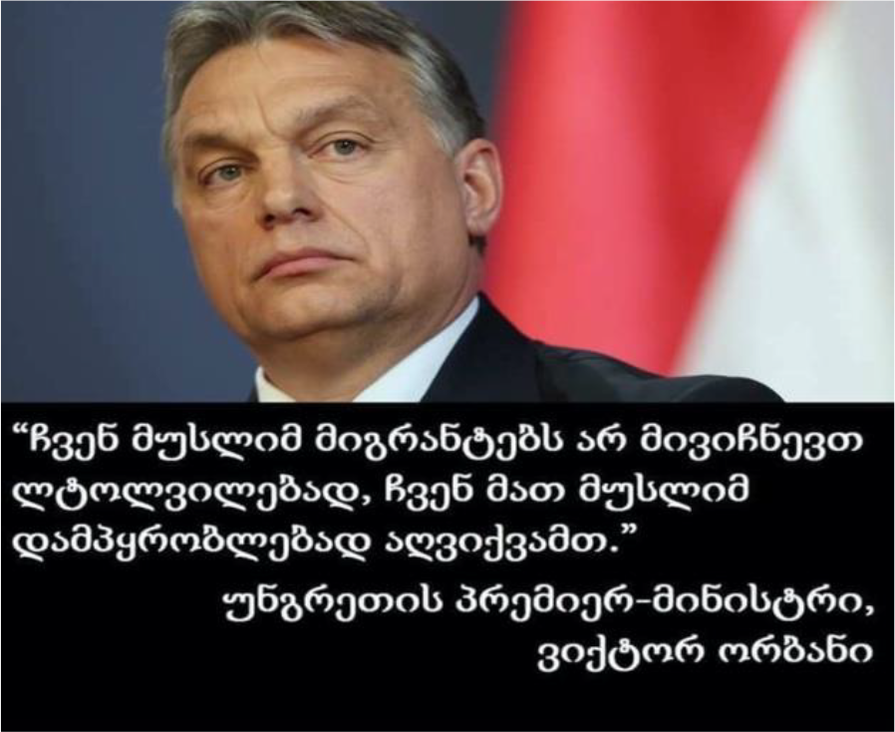

Another national-populist move by Georgian March was to announce the creation of so-called “public policing,” with the declared aim to control the “criminal behavior of illegal migrants.” This is in line with what Eatwell describes as denial of racism charges via distinguishing between “good” and “bad” immigrants and attaching normative labels to them (Eatwell Reference Eatwell2006). Two weeks before this announcement, the movement’s Facebook page intensified its production of posts with anti-immigrant sentiments and references to Europe. One included a photograph of Orbán with a quotation from him translated into Georgian: “We do not perceive Muslim migrants as refugees, we perceive them as the Muslim conquerors” (See Figure 5).Footnote 27

Figure 5. Screenshot 4 “We do not perceive Muslim migrants as refugees, we perceive them as the Muslim conquerors.”

In these terms, Orbán is considered an authority, a “successful external example,” and his words are framed as legitimization for anti-immigrant sentiments. In a subsequent interview with Primetime, Bregadze tried to legitimize “public policing” by referring to “Europe,” as if this practice already existed in many European states (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2018). Using framing strategies, the movement tried to legitimize its “public policing” initiative by interpreting and attaching it to Western practices. Table 1 summarizes the discourse fields and topics described above.

Table 1. Discursive Fields and Topics

References to European practice consistently appear in each of the discursive fields. In this form, they serve the legitimizing function for the movement’s proposed policy, as well as aligning GM with Western practice. Moreover, all three fields are integrated together in the members’ narrative while representing the movement and its identity. In explaining GM’s history and the reasons for its establishment, one of its leading members legitimizes the movement’s activities via framing European developments: “ … lands are not sold so ruthlessly in any of the European states, none of the European states has a migration issue in such an uncontrolled form, and by the way, not many European states have a decisive policy towards the marriage rights of same-sex people ….” (Nemsadze Reference Nemsadze2019, interview)

However, as demonstrated below, the references to Western practices are dubious in GM’s discourse and their legitimizing strategy goes together with anti-liberal narratives throughout the double construction of Europe and recontextualization of the associated values. Moreover, the members attempt to emphasize their affiliation with the Western national-populist actors in line with constructing the movement’s collective identity.

Immigration

Europe, or rather a particular construction of “the West,” has been a central point of reference throughout this discourse field. Topoi of analogy and reality Footnote 28 are simultaneously deployed in discourses about the “awakening” of Europe. Bregadze frequently refers to the issue of immigration in his interviews when asked about his reasons for establishing Georgian March, as he claims that “the same is happening in European states” and “Europe is awakening” (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2017a). This expression is also frequently used as a headline to posts on the movement’s official Facebook page. In the first case (topos of analogy) references are made especially to Orbán, the Polish government (Law and Justice Party), the Front National, Nigel Farage, and the German Pegida and Alternative for Germany (AfD). The same headline (Europe is Awakening) is used for a video of the Flemish youth group “Schild & Vrienden” expressing far-right, Euroskeptic sentiments and tearing up the EU flag. As for the topos of reality, another expression – “Sane (healthy) Europe” – is positioned on top of posts portraying cadres from the Polish nationalist movement on November 11, with a special emphasis on their poster “My Chcemy Boga” (We want God).Footnote 29 Furthermore, this phrase precedes the post framing an event from Hungary (a metonymical reference): “A healthy Europe [winking smile]. ‘Hungary: in order to increase the population, we need to improve friendly politics towards families instead of mass migration.’”Footnote 30

Hence, using argumentative strategies, the movement constructs and appeals to the “progressive” and exemplary image of Europe. In this way, an empty signifier – “European values” – carrying a positive connotation in public and political discourses in Georgia within the framework of involvement into EU integration processes, is affiliated with signifieds of nationalist governments, exclusionary politics, following the “will of the people,” anti-immigration proposals, and defending Christianity. Yet not the whole of Europe falls under this label; only strategically selected leaders are discursively deployed in the process of self-identification. In this matter, the Hungarian Prime Minister Orbán appears as the most frequent point of exemplary references as well as of suggested policies at the local level.

The progressive image of Europe promoted through the official foreign policy concepts is also being recontextualized. Anti-Western sentiments are provoked systematically through the movement’s discourse. This process is predominantly taking place via topos of threat,Footnote 31 in the sense that “this Europe” has chosen multiculturalism and liberalism and found itself in a “fatal situation.” Multicultural Europe is therefore responsible for “criminality and destruction” in its lands. In this construction of effectiveness, the “good” Europe does not allow immigrants for the sake of security, while in “the other,” criminality has increased because the proper measures were not taken. Thus, a subtle Euroskepticism goes along with recontextualizing the values previously ascribed to Europe, into those that place GM within this new construction of the “real Europe.” In such a way, the movement attempts, firstly, to socialize itself within the preferred ideological community, and secondly, to construct and legitimize itself and its raison d’être together with strategically mimicking some of the rhetoric, topic, and even the events. This narrative goes together with anti-Islamic discourse as seen in the leaders’ construction of what Europe ought to look like: “If there I will meet a person with a burka who hands me a kebab, that is not Italy anymore … then let’s delete Italy and let it be Morocco” (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2019, interview). As Froio and Ganesh (Reference Froio and Ganesh2019) conclude, one of the two main unifying interpretative frames for the far right in Western Europe is the idea of “civilizational conflict” with Muslims, which is also mirrored in GM’s anti-immigration narrative: “Our problem is double: people leave from here but others are coming. These others are of totally different belief. Even assimilation is not possible, right? i.e. it is impossible to assimilate a Georgian and an Arab, they are not even close” (Porchkhidze Reference Porchkhidze2019, interview).

As mentioned, anti-immigrant rhetoric is systematically displayed hand in hand with anti-Western attitudes. GM’s Facebook page occasionally shares videos supposedly depicting chaotic or criminal behavior “in Europe” involving people with dark skin or long beards. In most cases, the discourses are framed in such a way as to legitimize the connection of immigration with criminality. For example, a post from January 6, 2018 reports the following: “According to German governmental research, the increased number of violent crimes is related to mass migration.”Footnote 32 Although the news actually does not suggest any such correlation,Footnote 33 an incorporation of the high percentage and the reference to research serves to strengthen the narrative. Thus, framing of the narration serves to construct the topos of example, which is also a frequently used strategy in personal communications by the movement’s leaders. Another similar post concerning Italy shows a picture of a white female’s face covered by a dark skinned hand and offers the following interpretation: “A migrant sneaked into a hospital and tried to rape a pregnant woman in Italy.”Footnote 34 To sum up, the timing of the posts and the coherence of similar statements serve to negate the liberalism and multiculturalism of “this West” and reinforce traditional anti-Western attitudes (the negation of multicultural and liberal values).

Simultaneously, the movement constructs anti-immigrant discriminatory language in reference to the EU as well. Another set of posts build anti-EU discourse through endorsement of the belief that the EU will compel Georgia to receive migrants in exchange for the EU visa waiver. These sentiments are best demonstrated through a post containing a photo of Olaf Scholz with the quote: “In the case that Poland and Hungary do not start receiving migrants, Germany will reduce financial transfers to the EU budget.”Footnote 35 At the same time, the movement does not explicitly neglect Georgia’s aspiration to join the EU or NATO, but rather attempts to foment skepticism via topos of example.

The argumentative and framing strategies are therefore constantly deployed in reference to the West (Europe) and anti-immigrant language. The main demands advanced by GM during the protest – aggravation of migration politics and deportation of all “illegal migrants” – were legitimized by linking them to European values (representatives of the movement announced several times during the protest that “we should live with European values”). Bregadze further maintained in the interviews: “The fact that the US hardly allows citizens of Eastern Europe and Asia to enter the state does not mean their government is xenophobic, they are just securing their citizens. See what is happening in Europe: receiving Syrian refugees increased the level of criminality there” (Liberali.ge 2017). He therefore deploys both topos of analogue and topos of example (Wodak and Meyer Reference Wodak and Meyer2009, 13) in reference to the West, in an attempt to rationalize the content of his anti-immigration appeals. Simultaneously, he refers to the West in an attempt to deny xenophobia in the movement’s actions, framing it instead as an issue of security. Furthermore, the fourth point of the petition read during the anti-immigration protest reflected their demand “to adjust immigration policies to European standards.” Thus, “European values” are intended to be used as an argumentative strategy of moral evolution,Footnote 36 although, as analyzed above, the notion of “European values” is also recontextualized.

Besides borrowing the anti-immigration discursive field that has been the “hallmark of success” (Mammone, Godin, and Jenkins Reference Mammone, Godin and Jenkins2012) for right-wing populist parties throughout the past three decades, the movement also adopted discursive strategies (the association of “illegal” immigrants with criminal behavior), topics (illegitimate/unreliable government), and language (“foreign criminals”). Moreover, in terms of borrowed language, the movement’s initiative of “public policing” was legitimized not only by references to “the analogous initiative in Europe,” but also by the borrowed anti-immigration language. Discourses around the proposed initiative simultaneously nominated/categorized foreigners as outgroups and predicated them deprecatorily by locating “foreign illegals,” “criminals,” and “terrorists” together within one rhetoric, while also emphasizing the inability of the government to secure the people and control the “flow of terrorists and criminals.”Footnote 37 Consequently, the movement attempts to legitimize national-populist discourses via framing “European examples” and adopting/mimicking anti-immigration rhetoric, largely absent from prior right-wing discourses in Georgia.

Concisely, intensified anti-immigration discourses just before and after the announcement of the public policing idea serve to construct and reinforce prejudices about the outgroup and legitimize them via the framing of discourses and events in the West. Sandro Bregadze would continuously refer to “European practice” to legitimize his initiative throughout the interviews: “This will be civilized, European, and modern, because we have worked on tactics with our European friends. We want to create this for the benefit of our population. We are fighting for pure, Georgian, moral Georgia, and I am sure God will be on our side” (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2018, emphasis added). In these terms, “the European” is associated with notions of modernity and civilization, intended to legitimize the populist idea, which otherwise might be related to the destruction or delegitimization of the government. Bringing up examples from the “civilized West” aims to neutralize the accusation that they constitute a regressive, “dark” power. Moreover, Bregadze is creating an image of the movement as “consisting of people” and “working for people,” whilst the higher moral aim is connected to “Georgian Georgia.” Through such discursive strategies, his ambiguous, seemingly positive rhetoric is supposed to obscure the discriminatory content of the initiative, which is directed at the metonymically constructed group of “foreigners” and endorses prejudice towards them as criminals.

Alongside references to the “western analogs and examples,” the movement used local context to mobilize resentments. As Wagner (Reference Wagner, Christ, Heitmeyer, Dovidio, Hewstone, Glick and Esses2010) has put it, particular events and development of discourses greatly affect the triggering of anti-immigrant prejudices. The claimed reasons for creating a “national power” were framed as urgent and based on the case of an Iranian man accused of raping juvenile boys in one of the regions of Georgia. This case was synecdochally used in slogans such as “We will clean our streets of foreign criminals,” continuously heard during the first march and on their Facebook page. In this way, the leader generalized one Iranian man to the whole outgroup and categorized it through a criminalization strategy (“foreign criminals”) on the one hand, and created an in-group bond, a collective singular “we,” on the other. The Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) opened its electoral campaign with a similar slogan (Wir säubern Graz – Wir fegen das Übel aus der Stadt [We clean Graz – We sweep the evil out of the city]) in 2006 (Alliance Future Austria (BZÖ) 2007). Considering the absence of obvious links, these similarities indicate indirect transnational diffusion of national-populist anti-immigration discourses where new types of media are essential in disseminating the discursive style and frames.

Thus, the anti-immigrant, national-populist discourses of Georgian March, which have been absent from nationalist sentiments in Georgia before, result from a strategic adaptation and indicate indirect cross-national and cross-level diffusion of the discourse field, slogans, and respective language. A considerable part of this construction took place through online platforms, particularly the movement’s Facebook page. Within these discourses, new national boundaries do not exclude ethnic minorities, but shift towards the vertical exclusion of the “unreliable government” and horizontal exclusion of (mainly Muslim) immigrants.

Foreign Influence and the Local Establishment

When asked why Georgian March was fighting against George Soros, Bregadze turned to the habitual populistic dichotomy of “nationalists” and “enemies,” labelling Soros as the biggest enemy of the “Georgian people and Georgia” (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2019, interview). As with the migration issue, he referred to Hungary, whose leader “prohibited his activities and declared Soros persona non grata in the country” (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2017a). In order to legitimize this proposal, Bregadze referred to the “Europeanness” of Orbán, thereby attempting to frame the issue via authorization: “Prime minister Orbán is a celebrated European leader” (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2017a). This strategy complies with the discursive construction of a “new progressive Europe.” In these terms, Hungary is an exemplary case from Europe: within the context of diffusion theory, it can be explained not only by hierarchical models and the perceived prestige of (European) Hungary, but also by the structural equivalence considering the relative similarities of the Hungarian socio-political background and democratization paths with those of postcommunist Georgia.

Within this discourse field, GM strategically adopted discursive schemes avoiding any anti-Semitic references. In contrast with other far-right movements – both in Georgia and in other European countries – Georgian March circumvented notions of Jewish conspiracy altogether in their rhetoric. Nonetheless, their Facebook page has actively been publishing caricatures of George Soros under headlines such as “Eastern Europe against George Soros”Footnote 38 and “Europe has awoken,” attempting to legitimize their appeal to shut down the OSF office in Georgia. Protest against the OSF and foreign influence went hand in hand with anti-elitist appeals, as maintained by a leading GM member: “Political elite, journalistic elite, university elite, almost all of them are coming from Open Society Foundation. There are no other people in the elite … ” (Porchkhidze Reference Porchkhidze2019, interview). Moreover, the local elite is presented as privileged (“they have everything to live well in this poor country”) and as mediators of foreign interests in Georgia (“to do here whatever they ask of them there [in Europe and America]”) (Nemsadze Reference Nemsadze2019, interview). The demand to shut down OSF Georgia was presented as “the will of the people” and the group proposed that the matter be decided through a referendum. Using topos of analogy, the movement tried to legitimize this appeal:

If the government will not take the people’s will into consideration and will not prohibit the activities of Soros in Georgia, as happened in Hungary, Austria, and Israel, then protests by Georgian March will be harsher! … Georgian March will propose a referendum for prohibiting the activities of Soros and other NGOs that are financed from abroad, as they are pursuing a foreign interest within the state, intervene in sovereign governance, and hinder the democratic development of Georgia. Footnote 39

The initiative to decide this issue via referendum was attached to the “democratic development of Georgia.” The populist appeal for a better democracy is therefore concomitant with a prohibition on foreign finances in the non-governmental sector and linked to the “successful practices” of Central Europe and Israel. It is significant to notice that no reference was made to Russia, although the same proposal, using an identical argument that “foreign agents” intervene in domestic issues, was the basis of Russia’s constitutional amendment of July 2012 (The State Duma 2012).This fact could be explained through the invocation of “the West” and its juxtaposition to Russia within public and political discourses throughout the last two decades. In other words, GM avoids any association with Russia, while actively attaching its political decisions to the West and recontextualized “progress.”

In terms of diffusion of the rhetoric, Georgian March has adopted the Hungarian example and used it as a legitimizing tool for its national-populist discourse. Anti-Soros posts particularly intensified by the time of the second protest on February 25, 2017, for which the title and even the symbol of the event – “Stop Soros” – were copied from the billboards erected throughout Hungary during that country’s parliamentary election campaign.Footnote 40 Using authorization, the movement’s Facebook page published several posts notifying that “Austria has given a twenty-eight-day ultimatum for Open Society to leave the country” with the accusation that the organization was destroying state sovereignty and intervening in internal issues. Several days after the protest, deploying the topos of analogy of reasons, GM publicly announced their proposal for the referenda through which “Georgian people” would force the government to do what “European countries” are doing. Thus, in this case the diffusion is marked by the temporal sequence, together with apparent borrowing of discursive elements and allegedly indirect (media) channels of diffusing elements.

Cultural and Family Values

Another discursive field deployed by Georgian March concerns mobilization over fears of losing values. This field is closely connected to the aforementioned discourses about “foreign agents.” The populist dichotomy between “true Georgian people” and “traitors” is also invoked. In these terms, not only are national others or foreigners excluded from “the people,” but those living within Georgian society can also be cast as outsiders. The latter category is assigned the labels “Liberal-Sorosist” and “traitor.” In Bregadze’s words, “The Georgian media is hiding the truth from the people. No matter how long Georgian Sorosist media will block Trump and the victories of nationalists in Europe, these victories are like a tsunami, which will arrive in Georgia and overflow Liberast-Sorosist monstrosities… Be afraid traitors!!!”Footnote 41

Generally, the success of what Bregadze terms “national, honest, and faithful [religious] powers” in Europe and the US is labeled as an “achievement” throughout the movement’s discourses (Bregadze Reference Bregadze2017b). Moreover, deploying topos of analogy, the resurgence of “nationalists” is framed in hopeful terms that the same will happen in Georgia. The construction of similarities between the “Western” powers and Georgian March further serves to legitimize the movement in accordance with popular perceptions of the West in Georgia. However, GM explicitly advocates for reinterpreting the meaning of Europe in the country: “It is important that people understand what Europe is – and that it is not, as portrayed, composed of and for LGBT people and the like … in reality it is not like that … ” (Porchkhidze Reference Porchkhidze2019, interview).

At the same time, the movement implicitly endorses anti-Western sentiments, thereby maintaining its tendency to construct the double face of Europe. In this context, GM has provoked traditional anti-Western thoughts about the “expense” of the EU visa waiver. On the movement’s Facebook page, a video was published with the title: “A shocking confession: Georgia and Moldova got the visa waiver at the cost of a promise to legalize homosexuality … .”Footnote 42 Similarly, another post several days later claimed that “Georgia is becoming a shelter for foreign LGBT people … Bravo! Is this an aspiration to Europe?”Footnote 43 In this way, Georgian March sarcastically connected the sensitive (identitarian) issue to the country’s political course, simultaneously denouncing it in a subtle way. Accordingly, the anti-Western attitudes, although revealed elusively, have been an accompanying part of this discourse too.

The text on the post:

Prime Minister of Hungary: The silent majority, for whom traditions and family values are important, will defeat the global empire. According to Orbán, in the ideological clash there is the people, who “are fighting for the family, love the homeland, and secure their Christian roots” on the one side, and the global elite, with its network of Soros agents, on the other. The spirit of this era indicates that the silent, anti-globalist majority will achieve the glory in this clash.Footnote 44

This text on Figure 6 accompanying Orbán’s picture reflects on Bregadze’s frequent claim about the rise of national consciousness Europe-wide in response to the prevalent “liberastism.” In addition to the media and the governing elite, who permit “foreign influence,” NGOs are another focus of attack in this context. According to Bregadze, they are serving foreign interests in the country and undermine Christian identity. Hence, in the chain of equivalence (per Laclau and Mouffe Reference Laclau and Mouffe2001) homosexuality is linked with immorality, foreign influence, and the deprivation of national and Christian values. In terms of linguistic borrowing, Bregadze constructed the image of a “clash” between national ideology and “liberast-Soros” powers, much like Orbán’s rhetoric. As he maintained in his later Facebook posts: “The victory of national ideology is inevitable. No matter how hard the Liberast-Sorosist powers try, no matter how much money they spend, their defeat is a historical necessity.”Footnote 45

Figure 6. Screenshot 5: Orbán on Traditional and Family Values

This marks a borrowing of the discourses created elsewhere, with simultaneous attempts to legitimize it via moral evolution and narratives about the future. This example mirrors the general strategy of using the “awoken West” and discourses of “successful” Western national-populists in the movement’s discourses. The temporal sequence of the announcements by Orbán and Bregadze, and the similarity in their content, once more demonstrates the process of diffusion taking place through the media platform.

Diffusion and adaptation are strategic processes dependent on contextual variables within this discursive field too. Even in the context of Christian values – the central point of homophobic discourses – the movement has not applied the traditional anti-Western discourses that would position Russia as the “lesser evil” with which to align in defending Christianity. Even the expression “homosexual propaganda” resembles discourses in Russia in 2012 within the politics of “returning to traditional values,” through which “foreign agents” and “propaganda of homosexuality” were banned at the constitutional level (Persson Reference Persson2015). However, despite the similar content and expressions, the Russian case has not become a point of reference for Georgian March. Instead, the movement has been trying to rediscover legitimization through the idea of Christian Europe.

Conclusion