Introduction: A shrine in Taipei

At ten minutes to the hour from nine to five o'clock every day, buses unload crowds of tourists in front of the gate of the Taipei National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine (Guomin geming zhonglie ci), where they will soon be mesmerized by the regimented goose-stepping and gun-toting performance of the impeccably uniformed honour guards. A few adventurous visitors make their way to the inner buildings and meander along the map-decorated hallways where the spirits of the Chinese revolutionaries are enshrined. However, the shrine is more than a tourist attraction, it plays an important ritual and political role. Several times a year, the Republic of China's highest-ranking leaders and generals are required to visit the site. This shrine, which honours the most hallowed martyrs of the Republic of China, is a site of contested memories.

The Taipei Martyrs’ Shrine was initially intended to serve as an altar to the forefathers of the Chinese nation, promoting political loyalty and national unification. By selectively memorializing the loyal self-sacrificing dead from the 1911 revolutionary moment to construct a national biography, the Republic of China established a myth about the origins of the nation and its legitimacy. According to traditional understanding in many Asian societies, war martyrs dying violently and away from home constituted ‘bad deaths’, the moral negativity of which could be absolved by the positive patriotic merit.Footnote 1 By so doing, the Nationalist Party (Guomindang) managed to retain legitimacy domestically and internationally throughout its rule in China and later Taiwan. By celebrating violent and premature demise, traditionally dreaded as a bad way to die, as a ‘good death’, the Nationalist state reinforced the myth of necessary sacrifice for the sake of the nation.

After being defeated by the Communist forces in 1949, Chiang Kai-shek (1887–1975) took the displaced spirits of his loyal dead to Formosa/Taiwan—a former colony that was administered successively by the Dutch, the Spanish, the Qing, and the Japanese over the course of more than 300 years—and enshrined them in the Japanese-built National Protection Shrine (Gokuku jinja). Renovated and renamed the National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine in 1969, the structure served as the national altar of the Chinese Republic in exile. During the Cold War era, the enshrinement of Nationalist fallen soldiers, the spring and autumn sacrifices in the presence of prominent political leaders, and visits by foreign dignities were carried out with solemnity and formality. The shrine, which embodies the authoritarian rule of the Nationalist Party, has in recent decades become a space of contentious memories. Certain recollections, such as those of the foreign troops who fought in the Taiping Civil War (1850–1864), faded with time.Footnote 2 Yet, the Republican-era heroes still have an audience for commemoration up until today. Indeed, despite the legacy of Nationalist authoritarianism, the shrine and the enshrined dead have found a new role in defining the island's identity and status in both the domestic and international political arenas. Although enshrining Republican-era heroes is part of the Nationalist regime's nation-building project, these men also embody the struggle against imperialism (of China's past) and authoritarianism (of China's present).

By analysing the genealogy of the Taipei National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine and its enshrined dead, this article sheds new light on the evolution of cross-Strait politics. Lin Hsiao-ting characterizes Taiwan as an ‘accidental state’ created from serendipity.Footnote 3 In this sense, it is understandable for this island to eke out its legitimacy in any way, including holding on to its dead. Although the Taiwan Strait has attracted ample scholarly attention, I propose to discuss this topic by way of the dead, who, as Katherine Verdery claims, can enchant, enliven, and enrich the study of politics.Footnote 4 Moreover, Hans Ruin argues, ‘[p]olitics—as communal organization and action—involves the dead through the ways in which the living community situates, responds to, and cares for its dead’.Footnote 5 Hence, I argue, the dead lead a fruitful inquiry into Taiwan's political space.

Discussing the dead is a way to address how the Chinese Civil War (1946–1949) is still fought in memory.Footnote 6 The dead, in Verdery's words, ‘line people up with alternative ancestors and thereby … reconfigure the communities people participate in’.Footnote 7 In the case of Taiwan, even though the Martyrs’ Shrine fails to represent the multi-ethnic population of the island, which has been shaped by diverse aboriginal tribes, centuries-long waves of migrants, and several colonial eras, the site of commemoration has served as a focal point for generations of the island's leaders aiming to cultivate national belonging. Such cultivation is a part of war memorialization, which has also played a prominent role in mainland China politics, especially with the demonstration of martial power on the occasion of the seventieth anniversary of the Second World War in Beijing in 2015.Footnote 8 Although commemoration in Taiwan has been quieter, remembering the past is still a delicate matter.Footnote 9

Architecturally modelled on the Forbidden City in Beijing, the Taipei Martyrs’ Shrine nonetheless stands in stark contrast to its counterpart in mainland China—the grandiose obelisk Monument of the People's Heroes in Beijing. The Beijing monument represents the Chinese Communist Party manifesto carved in stone, celebrating the Chinese people's heroic resistance against foreign powers and ‘simultaneously denying their autonomous power’.Footnote 10 Originally intended to host the martyrs of the Republic, the Taipei shrine embodied the legitimacy of the Nationalist Party in Taiwan and the party's claim over China during the Cold War. Although both commemorative spaces in Beijing and Taipei are contested by voices from the people, the Taiwanese government arguably cannot monopolize the collective memory to the extent that the Chinese leaders do in contemporary China. At present, the Taipei shrine is a proclamation that Taiwan has followed a different trajectory from that of China. Even though this affirmation does not give voice to all social and political groups in Taiwan, it is part of the search for a common historical experience and memory for the people on the island.Footnote 11

The making of national martyrs in Republican China

In keeping with the notion that the dead are often conjured to legitimize the nation, much effort has been expended on crafting national martyrdom since the founding of the Republic of China in 1911. The ideal was first modelled upon anti-imperial insurgents who plotted armed attacks against the imperial government and died a violent death. As the fall of the centralized empire generated multiple claims to power, the enshrined heroes were hailed for their adherence to a particular ideology and regime. Over the course of the first half of the twentieth century, the Nationalist, Communist, and Japanese-backed regimes in China engaged in the politics of death—creating and employing narratives of commendable deaths in the war over sovereignty and legitimacy.

In 1912, the Ministry of the Army of Sun Yat-sen's Nanjing Provisional Government ordered provincial governments to convert the Manifest Loyalty Shrines (Zhaozhong ci) built to honour late nineteenth-century military leaders in the Taiping Civil War into Great Han Loyal Martyrs’ Shrines (Da Han zhonglie ci) to honour Republican revolutionaries.Footnote 12 The new ideal of martyrdom promoted by the Republic was conceived in the context of the antagonistic relationship between empire and nation, and between the Manchu and the Han. Local communities were ordered to offer sacrifices to the Republican martyrs biannually and perpetually comfort their loyal souls.Footnote 13 The spring sacrifice was set for 15 February—the solar date of the Republican Unification (Minguo tongyi). The autumn sacrifice was set for the 19th day of the eighth month—the lunar anniversary of the Wuchang uprising which led to the overthrow of the Qing empire in 1911.Footnote 14 Building shrines, setting national days, and prescribing mourning rituals, as Takashi Fujitani maintains, ‘[brought] the common people into a highly disciplined national community and a unified and totalizing culture’.Footnote 15

The list of martyrs chosen by Sun Yat-sen reflects the new Republic's exaltation of violence, which he viewed as the means to achieve his political goals. At the top of the list was Zou Rong (1885–1905), who argued for the racial differences between Chinese and Manchu people and advocated a violent end to the Qing rule.Footnote 16 The register of Republican martyrs included several assassins who had targeted Qing officials. Shi Jianru (1879–1900), a member of the Revive China Society (Xingzhong hui), was beheaded for plotting a bomb attack on the governor of Guangdong in 1900.Footnote 17 A member of the Restoration Society (Guangfu hui) and Northern Assassination Corps (Beifang ansha tuan), Wu Yue (1878–1905) died while attempting a suicide-bomb attack on Qing commissioners.Footnote 18 Xu Xilin (1873–1907) was publicly dismembered after assassinating a Manchu bannerman.Footnote 19 Yang Zhuolin (1876–1907) was executed for attempting to murder a Manchu governor-general. Wen Shengcai (1870–1911) was beheaded for shooting dead a Manchu general.Footnote 20 Peng Jiazhen (1888–1912) perished by his own explosives while trying to assassinate a Manchu commander.Footnote 21 Collectively, these radicals are defined by their use of armed attacks to broadcast their political ideals.

The most celebrated martyrs were from the Yellow Flower Hill (Huanghuagang) uprising that took place on 27 April 1911 (29 March in the lunar calendar). A group of local gentry, businessmen, overseas students, and secret society members, some of whom belonged to Sun Yat-sen's Revolutionary Alliance (Tongmenghui), staged an armed revolt in Guangzhou. Because their plan had been leaked to the authorities, the imperial troops crushed the rebellion. After the fall of the Qing empire, Republican supporters and Nationalist Party members built a commemorative park to house their remains and named it Yellow Flower Hill. The martyrs’ popularity in the public discourse, fostered by their youth and tragic end, strengthened the legitimacy of the new Republic.

Sun Yat-sen's idea of uniting the nation through shrine building and martyr commemoration was furthered by the Beiyang government (1912–1927) and the Nationalist government (1928–1949).Footnote 22 A part of the Altar to Agriculture (Xiannong tan) in Beijing was converted into the Loyal Martyrs’ Shrine where authorities held an annual public sacrifice for the revolutionaries on 10 October, the founding anniversary of the Republic. After establishing a new regime in Nanjing in 1928, Chiang Kai-shek expanded the national martyr roster to include National Revolutionary Army soldiers who had died during the Northern Expedition (1926–1928) and contributed to a nominal unification of China. Hundreds of local temples were converted into shrines for Republican martyrs. The shrine-building project of the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek was interrupted in 1937 by the Japanese invasion of southern China.Footnote 23

Following its invasion of China, the Japanese military constructed hundreds of Shintō shrines and compelled the occupied population to pay tribute to Japanese deities and war heroes as a sign of loyalty to the Japanese empire.Footnote 24 In the 1930s and 1940s, the Japanese military built the Loyal Spirit Towers (Chureito [Japanese], Zhongling ta [Chinese]) in Changchun, Mukden, Beijing, and Jilin to host the ashes of Japanese soldiers who had died during the military campaigns to take over these cities.Footnote 25 Local populations were made to pay homage to the souls of their invaders. Japanese tourists were organized to visit these Loyal Spirit Towers and former battlefields in China, where they discovered a new sense of attachment to the empire and pride in its conquests.Footnote 26

After Chiang Kai-shek relocated the Nationalist government to China's southwest and carried out the War of Resistance against Japan, his rival Wang Jingwei (1883–1944) promoted collaboration. In 1940, Wang led the Reorganised National Government under Japanese control in the capital of Nanjing. To bolster his legitimacy, Wang made regular sacrifices at the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum in Nanjing—the ancestral altar of the Chinese Republic—and the Yellow Flower Hill Martyrs Commemorative Park in Guangzhou—the birthplace of the Nationalist regime.Footnote 27 Wang not only personally held public memorials for ‘Peace Movement’ (Heping yundong) martyrs with high-ranking officials in attendance but also ordered Christian churches and Buddhist temples to hold vigils for them.Footnote 28

Notably, the collaborationist regime celebrated deaths due to illness or disease as evidence of dedication to the nation. ‘Death by overexertion’ (jilao binggu), a criterion for honours, covered various circumstances, from heart and lung disease to mental and physical deterioration. For example, Lieutenant Lü Zhenbang died of pulmonary disease (feibing) after a few months of ineffective Chinese medicinal treatment.Footnote 29 After Sergeant Luo Rongxun overexerted himself at work (jilao guodu), he developed ulcers all over his limbs and eventually died.Footnote 30 Lieutenant Colonel Ceng Kai's exertions while on duty weakened his body and he subsequently died after contracting tuberculosis and developing diabetes.Footnote 31 After 26-year-old Lieutenant Lin Zhaohai developed tuberculosis from overwork, he coughed intensely and lost a lot of blood: his ‘physical body wasted away and his mental state declined, leading to death’.Footnote 32 A night watchman, Mao Hezhuan, was so dedicated to his task that he paid no attention to his declining health and died from ‘long-term exertion that injured vital organs’.Footnote 33 All of the men were awarded death gratuities according to their ranks and merits. Some scholars argue that tuberculosis was constructed as a disease caused by unhygienic practices specific to the Chinese family and society.Footnote 34 The abovementioned examples show that tuberculosis was also viewed as a disease of exceedingly dedicated citizens. With this view, the collaborationist regime turned a public health crisis into a series of personal demonstrations of patriotism.

Likewise, the Communist martyr was defined by their adherence to the ideological and political enterprise, as evidenced by the exclusive compensation policies. In 1932, the Hubei-Henan-Anhui Soviet government honoured its soldiers and bereaved families according to the Wounded and Fallen Red Soldier Compensation Regulations.Footnote 35 In 1935, the People's Congress of the Communist Provisional Central Government promulgated a new policy to compensate and commemorate fallen members of the Red Government and the Red Army.Footnote 36 In the 1940s, crediting the imminent victory against Japan to the people's heroic spirits, Mao Zedong (1893–1976) suggested that a funeral and memorial be arranged for ‘any in our ranks who has done useful work’.Footnote 37 In 1951, the newly established People's Republic of China granted ‘the title of martyr’ (lieshi chenghao) to fallen civilian fighters and workers who ‘cooperated with military or public security troops, participated in war-related activities, or carried out armed struggle behind the enemy line’.Footnote 38

To compete, the Nationalist government in its exiled capital of Chongqing promulgated a series of overlapping regulations to honour its loyal dead.Footnote 39 During the 1930s and 1940s, tens of thousands of fallen party members, bureaucrats, soldiers, local militiamen, citizen soldiers, and civilians who fought against the Communist, Japanese, and collaborationist forces were enshrined in hundreds of county-level Loyal Martyrs’ Shrines (Zhonglie ci) throughout China.Footnote 40 The measures to establish shrines and memorialize the worthy dead were intended to integrate communities into a single nation that shared the same political interests. The state also prepared communities that had experienced tremendous loss for further sacrifice by making the war dead visible to the public through commemorative rituals.

For many American Civil War soldiers, a ‘good death’ on the battlefield was defined by utterances of love for God at the moment of passing.Footnote 41 For the Chinese combatants and civilians, dedication to the political cause became the criterion for a death worthy of honour. Martyrdom was conferred by agony in battle, dismemberment by public execution, or suffering from incurable illness in a hospital bed. So long as the death was for a righteous cause, it was a good death. The government, for its part, would provide bereaved families with stipends. The living would take care of the afterlife with regular offerings. Because posthumous care was desirable in the making of a ‘good death’, the defeated Nationalists continued to offer sacrifices to their national dead in Taiwan. The rhetoric of personal sacrifice for the greater political good that provided the foundation of the National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine in Taipei, however, led to tensions when the political domination of the Nationalist Party began to be challenged.

Appropriating spiritual power

After the Civil War (1946–1949), the Nationalist Loyal Martyrs’ Shrines in China were decommissioned. Along with over one million Nationalist leaders and supporters, the banished souls were evacuated to Taiwan, where they would continue to receive appropriate rituals and sacrifices. Many Shintō shrines and Japanese monuments on the island were converted by the Nationalists into martyrs’ shrines and patriotic sites.Footnote 42 In Taipei, Chiang Kai-shek transformed the Japanese-built National Protection Shrine (see Figure 1) into a site where sacrifices were offered both to anti-imperial revolutionary martyrs and to fallen soldiers who had fought on the side of the Nationalist regime.Footnote 43 The conversion of the National Protection Shrine was meant not only to deprive the Japanese dead of their offerings but also to appropriate the site's spiritual power.

Figure 1. A photograph of the Taiwan National Protection Shrine. Source: Taiwan National Protection Shrine Construction Committee, Zhenzuo jinian Taiwan huguo shenshe (The township celebrates at Taiwan National Protection Shrine). National Museum of Taiwan History. Date: 1942–1944.

The National Protection Shrines were part of Japan's empire-building project. In the late nineteenth century, hundreds of memorials for the war dead, namely the Soul-Summoning Shrines (Shokonsha), were built throughout the Japanese empire, some on the actual war burial grounds. At the turn of the twentieth century, these shrines were renamed National Protection Shrines. One of them was constructed in Taipei in 1942 to commemorate fallen soldiers of the ongoing war in Asia.Footnote 44 In Singapore, the Japanese destroyed the Shintō shrine and the Loyal Spirit Tower at the end of the Second World War.Footnote 45 Nonetheless, the National Protection Shrine in Taipei survived and became the hosting place for the spirits of Nationalist soldiers. Due to its location, the structure was called the Yuanshan Loyal Martyrs' Shrine.

The initial conversion was rather hasty, as revealed by the glaring gap between the wooden signage and the left column. An ill-fitting board was hazardously nailed across the torii (Shintō shrine's gate). The inscription—‘The great spirits last for eternity’ (haoqi qianqiu)—referred to the spirits of the Nationalist martyrs of the War of Resistance (see Figure 2). The layout of the National Protection Shrine and its Japanese elements, such as the stone lanterns, remained untouched. With this appropriation, the Nationalist Party grafted itself onto the remnants of the Japanese occupation era, replacing Japan as the new legitimate power.Footnote 46

Figure 2. Chiang Kai-shek, his wife Soong Mei-ling, and Nationalist high-ranking officials at the Yuanshan Loyal Martyrs’ Shrine holding a memorial service for fallen officers and soldiers. Source: Academia Historica, President Chiang Kai-shek Archives (CKS), AH 002-050101-00085-003. Date: 1946.

After losing the Chinese Civil War, the Nationalist government saw a critical need to care for the evicted spirits of its loyal dead.Footnote 47 With its newfound status as the seat of the Republic of China, the island was made to adopt the ancestral revolutionaries of the Nationalist Party. Chiang Kai-shek ordered Japanese features to be removed from the National Protection Shrine, including the torii gate, and introduced many traditional Chinese architectural elements such as curved roofs and intricate lattices on three-bay gates. The properly hung sign in 1950 read ‘Loyal Martyrs’ Shrine’ in Chiang's calligraphy. Honour guards bearing flags of the Republic of China flanked the gate, which was draped with a banner reading ‘The Ceremony of Revolutionary Predecessor Remembrance and Spring Sacrifice for Fallen Officers and Soldiers’ (Geming xianlie jinian ji chunji zhenwang jiangshi dianli) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Yuanshan Loyal Martyrs’ Shrine during the spring sacrifice for national martyrs. Source: Academia Historica, CKS, AH 002-050102-00001-136. Date: 29 March 1950.

In 1958, the Nationalist government began introducing a more Chinese aesthetic. In meetings with representatives from the Taipei municipal government, the Ministry of Defence, and the Ministry of the Interior, a plan was made to model the new shrine after the Linggu Temple and the commemorative tower for fallen officers and soldiers in Nanjing. Some expressed concern that the Yuanshan Martyrs’ Shrine was built on the ground of a Japanese Shintō shrine, but the decision was nevertheless made to move forward.Footnote 48 The choice reflected the Republic of China's self-portrayal as the preserver of traditional culture. After the minister of defence complained about the inappropriate features of the martyrs’ shrine, the Japanese-style stone lanterns along the walkway were replaced with Chinese-style lampposts.Footnote 49 The Sinified site served as the provisional capital's Loyal Martyrs’ Shrine throughout the 1960s before gaining its national status in later decades.

Under the Nationalist regime, China's main commemorative mode continued to be defined by offerings of sacrifices to spirit tablets inhabited by loyal souls in dedicated shrines. During the spring and autumn sacrifices, the president, assisted by the head of the Five Yuans (the Executive, Legislative, Judicial, Examination, and Control branches of the government), presided over the ceremony. The spring sacrifice was set for 29 March, the anniversary of the Yellow Flower Hill uprising (also chosen as Youth Day), and the autumn sacrifice for 3 September, the anniversary of the end of the Second World War (also chosen as Armed Forces Day). The ceremony began at ten o'clock and lasted half an hour, during which time participants played music, presented flowers, read elegies, and made three bows. During the ceremony, the martyrs’ spirits were conjured up to ‘partake in the offerings’ (shang xiang).Footnote 50 Each year, Presidential Office staff drafted a new elegy with content that emphasized the transcendental nature of martyrdom. For instance, the elegy drafted for the president to recite in 1950 underlined how the honour of martyrdom meant an immortal afterlife: ‘the ordinary people become nothing when they die; only the loyal and the self-sacrificing ones do not when they pass’ (Heng ren zhi si, jie gui wu wu, wei zhong yu lie, sui yun er bu).Footnote 51 In the 1950s and early 1960s, only the revolutionary predecessors and fallen officers and soldiers could enjoy the sacrifices. The 1967 elegy read during the spring sacrifice included the ‘martyred kindred’ (sinan tongbao).Footnote 52 In 1968, Zhang Qun (1889–1990), an adviser in the Presidential Office, proposed to officially invite representatives from the armed forces, civil bureaucrats, students, and martyrs’ relatives to participate in the ceremony.Footnote 53 The commemorative realm became mandatory for most of the population.

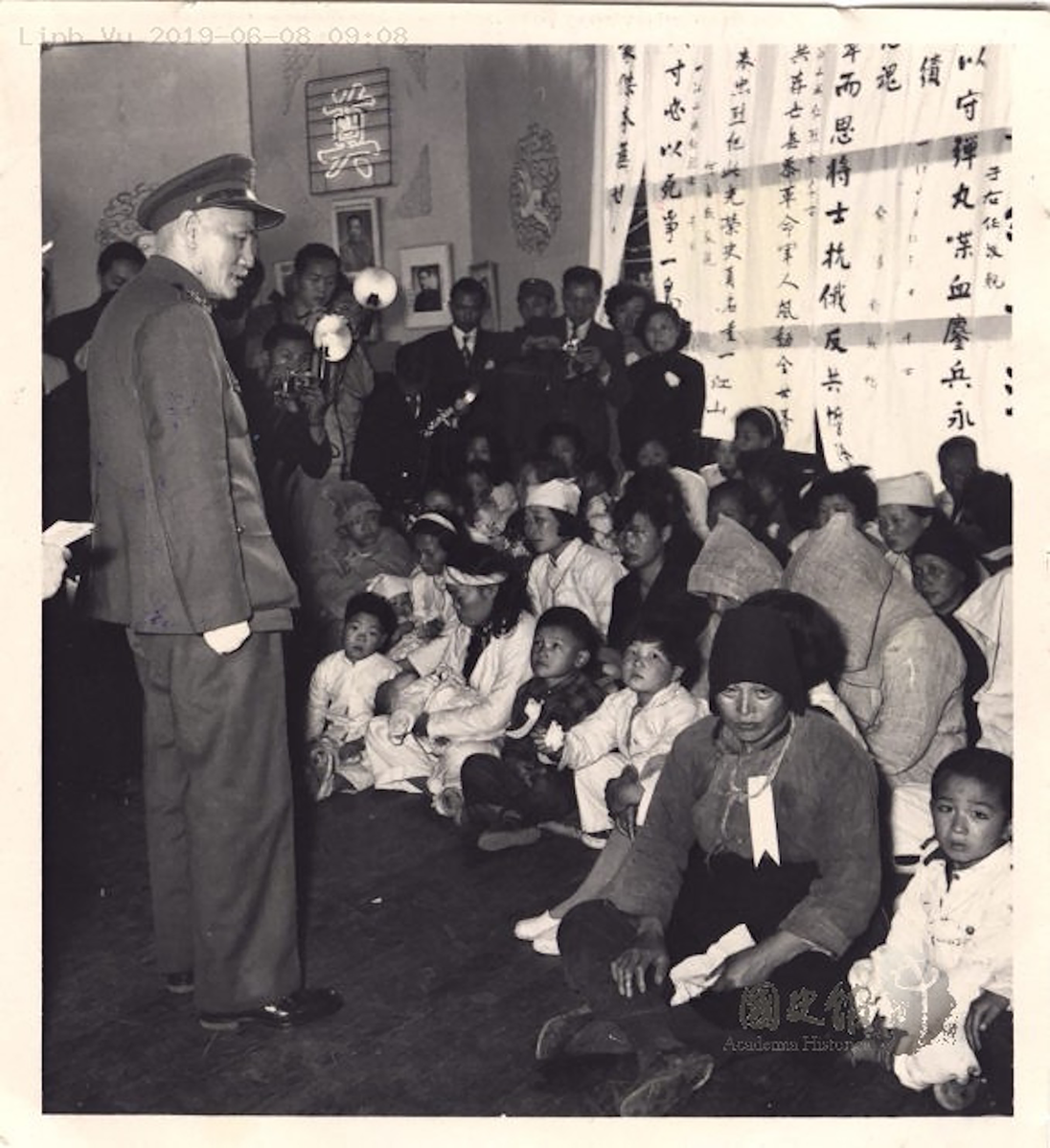

At enshrinement ceremonies and public sacrifices, relatives were expected to follow the rituals of political mourning. Yet, traditional ways of mourning found their way into the commemoration of the 1955 Battle of the Yijingshan Islands.Footnote 54 The palpable sorrow on the faces of many attendees stands in striking contrast to the content of the banner in the background extolling the Nationalist soldiers who fought and died in the fierce battle (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Chiang Kai-shek personally consoling relatives of the Yijiangshan Islands martyrs during the memorial service. Source: Academia Historica, CKS, AH 002-050102-00004-021. Date: 1955.

The relatives, mostly women and children gathering in relaxed postures on the ground, are dressed in customary funerary attire of rough hemp cloth and headbands that correspond to different degrees of mourning. Rebecca Nedostup frames the contrast between these relatives in dishevelled garb and the surrounding military officers and urban bureaucrats in Western suits and qipao (Chinese women's long gown) as the encounter between ‘two regimes of mourning’.Footnote 55 One was the government-dictated solemn ceremony to incorporate fallen soldiers and their relatives into the national family, with Chiang Kai-shek as the mourner-in-chief. The other comprised mothers, wives, and children mourning their sons, husbands, and fathers. The intense emotions of war and displacement emitting from the gaze of the grieving relatives undermines the state effort to prescribe how the Yijiangshan martyrs would be remembered.Footnote 56 However, the family quickly retreated into the background during commemorative events in the late 1950s, which coincided with the literal concretization of the national shrine to martyrdom.

A new commemorative materiality

As the Nationalist's plan to recapture the mainland became less likely, Taiwan became the permanent homeland for both the living and the dead of the Republic. In 1963, General He Yingqin (1890–1987), one of the most prominent politicians in the Nationalist Party, recommended renovating the Yuanshan Martyrs’ Shrine. Ground was finally broken four years later. Although it was estimated at 36 million yuan, the project ended up costing 53 million yuan, an expense that was shouldered by the central government, the Taiwan provincial government, and the Taipei municipal government.Footnote 57 The finished shrine occupies an area of 52,000 square metres (about 13 acres), of which one-tenth is covered by the structure and the rest is open space. The shrine honours over 400,000 martyrs, individually and collectively. The Ministry of Defence managed the shrine. The Nationalist Party's Central Executive Committee approved how the shrine ‘expresses the national characters of solemnity and grandeur’ (biaoxian zhuangyan hongwei zhi minzu texing).Footnote 58 The inaugural ceremony in March 1969 included over 2,000 participants. The minister of the interior officiated at the civilian martyrs’ wing with the assistance of the head of the Five Yuans. The minister of defence officiated for the military martyrs with the assistance of the chief of staff and the commander-in-chief of five branches of the armed forces. Representatives from government offices and the Nationalist Party, students, and martyrs’ children also attended the ceremony.Footnote 59

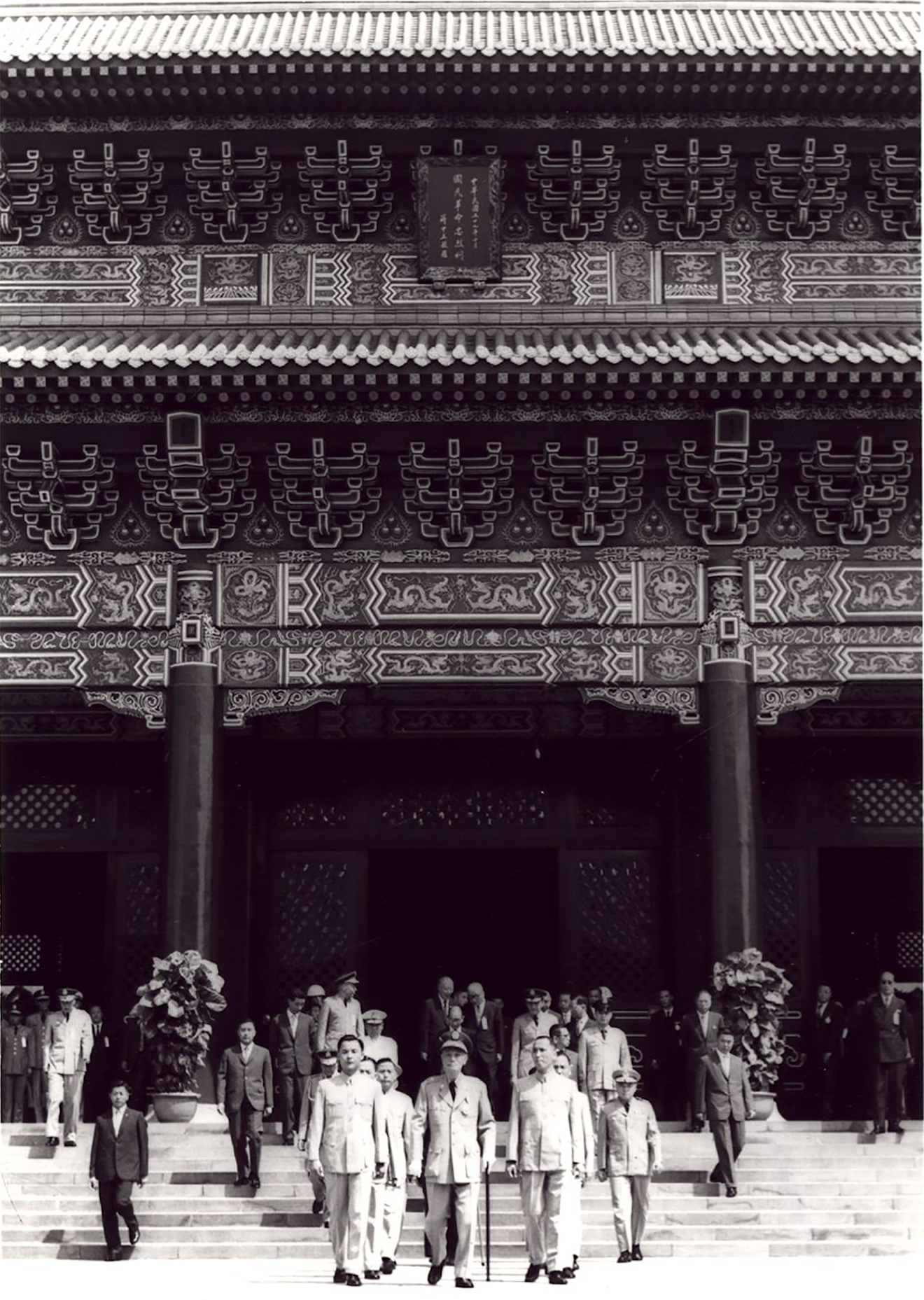

The renovated shrine demonstrated that Chiang Kai-shek had kept his promise to the soldiers by ensuring that they would receive sacrifices from the state for eternity. The unassuming wooden board on top of the great hall (dadian) in Chiang's calligraphy can only be read from up close: ‘National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine, 1969, dedicated by Jiang Zhongzheng [Chiang Kai-shek]’ (see Figure 5). During the 15-month renovation, Chiang was reported to have inspected the site 17 times, despite his declining health. He was often photographed walking around the shrine with a cane.Footnote 60 Chiang religiously performed the biannual spring and autumn sacrifices to the national dead until late 1971, when he was too weakened to continue.

Figure 5. Chiang Kai-shek and senior officials at the Martyrs’ Shrine performing the autumn sacrifice for the national martyrs. Source: Academia Historica, CKS, AH 002-050101-00116-173. Date: 1971.

The new shrine also accepted new inhabitants. In March 1970, Chiang Kai-shek approved the enshrinement of martyrs from the island's past, such as Lo Fu-hsing (1886–1914), Yu Qingfang (1879–1916), Mona Ludao (1880–1930), and Hanaoka Ichirō (?–1930). These martyrs were Hakka Chinese, overseas Chinese, and aboriginals who had resisted Japanese colonial rule (1895–1945). The son of a Hakka Chinese businessman and a local woman in Batavia (the capital of the Dutch East Indies), Lo Fu-hsing was inspired by Sun Yat-sen's ideology to revolt against the Japanese authorities in the 1913 Miaoli Incident. Yu Qingfang led the 1915 Ta-pa-ni Incident, a large-scale millenarian armed revolt against Japanese rule.Footnote 61 Mona Ludao led some 300 indigenes in raiding the government arsenals and attacked Japanese nationals in the 1930 Musha (Wushe) Incident.Footnote 62 Hanaoka Ichirō, an aborigine educated in the Japanese colonial order, committed seppuku (ritual suicide by disembowelment) when the authorities crushed the rebellion in 1930.Footnote 63 These incidents led to the persecution of thousands of people on the island. By enshrining these anti-colonial figures, the Nationalist leadership sought to portray them as loyal citizens of the Republic of China who had sought to ‘recover’ the motherland from Japanese invaders.

Today, the shrine still boasts its imperial style with glazed tile roofs, painted ceilings, striking vermillion pillars, and dark marble floor.Footnote 64 The building material, however, is reinforced concrete, instead of traditional wood and brick. The area is fenced by crimson walls on three sides and backs onto the mountain. The main entrance is adorned with a traditional Chinese architectural three-bay arch which is adorned with expressions praising martyrdom: ‘dying for a cause, revolting for righteousness’ (chengren quyi), ‘leaving a good reputation for all eternity’ (wangu liufang), and ‘loyalty and righteousness for a thousand years’ (zhongyi qianqiu). In the courtyards are camphor and pine trees, symbols of loyalty and longevity. The doorway is decorated with ornate lintels composed of four hexagonal shapes and the roofs are adorned with figures of immortals and mythical beasts. Plum blossoms, associated with the ephemerality of youth and beauty, as they bloom splendidly and fade quickly, are also used as a decorative motif on the shrine roof. As in many traditional temples, the main gate is flanked by a pair of male and female lions to protect the shrine from spiritual harm.

Upon entering the main gate, visitors find themselves in the outer courtyard where the bell pavilion and the drum tower are located. A bronze statue of the martyr Lu Haodong (1868–1895), who designed the Nationalist Party flag, stands on the first floor, and a colossal bell is hung on the second floor of the pavilion. The tower has a status of Shi Jianru, one of the revolutionary predecessors, and the second floor has a huge drum. Bells and drums are common features of religious establishments. The bell and drum in the shrine, however, are associated with awakening the people to the revolutionary cause.Footnote 65 Passing through the mountain gate (shanmen) into the inner courtyard, the visitor then faces the great hall (dadian). On the left is the hall of civilian martyrs and on the right is the hall of military martyrs.Footnote 66

He Yingqin's 1963 inscription was carved on a stone tablet installed at the entrance of the shrine. He dedicated it to the martyrs who died prior to the foundation of the Republic, as well as during the anti-Yuan Shikai (tao Yuan) campaigns, the Constitution Protection Movement (hu fa), the Eastern Expedition (dongzheng), the Northern Expedition, the anti-Japanese campaigns (kang Ri), and the various missions to punish rebels (tao ni).Footnote 67 In addition, the inscription refers to the suppression of bandits (jiao fei) and the campaign to quell disorder (kanluan). The former refers to the encirclement campaigns from 1932 to 1935 against Communist bases (soviets) in Jiangxi, Hunan, and other provinces in southern and central China, and the latter to the total mobilization of combatants, civilians, and resources to fight Communist forces during the Chinese Civil War. He Yingqin's words firmly establish the history of the Republic of China thus far as a series of campaigns against internal and external enemies. All powerholders contending with the Nationalist Party and the Nationalist regime are reduced to rebels, bandits, and criminals.

At the entrance of the inner courtyard are two large bronze reliefs, one that commemorates the 1911 Yellow Flower Hill uprising and the other, the 1932 First Battle of Shanghai, with captions in Chinese, English, and Japanese. Although Sun Yat-sen's role in 1911 was minimal and the New Army mutiny in Wuchang was one of the reasons the Qing empire crumbled, the caption credits the Yellow Flower Hill uprising with laying the foundation of the new Republic. According to the caption, the uprising in Guangzhou, plotted by Sun Yat-sen and led by Huang Xing, triggered nationwide revolts. One of the revolts was the October uprising in Wuchang, which overthrew the Qing government and established ‘the first democratic China’; the caption of the First Battle of Shanghai states that the National Revolutionary Army under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek ‘fought extremely bravely’. Here one finds neither vilifications of the Qing government, as seen in the Taiping Revolution Museum in Nanjing, nor denouncements of ‘the great slaughter’ (da tusha), as seen in the Memorial Hall of the Victims in the Nanjing Massacre.Footnote 68 The history here is that of China's becoming a nation.

The hallways, or ‘walking galleries’ (zouma lang), of the Taipei Martyrs’ Shrine are another example of the state's attempts to establish legitimacy, ‘through the rearrangement of space and the rewriting of history’ to use Chang-tai Hung's words.Footnote 69 Visitors are taken through the history of the Republic from the late nineteenth-century anti-Qing uprisings to the First Taiwan Strait Crisis in the 1950s. The reliefs, head busts, paintings, and memorabilia on display introduce visitors to a historical narrative that prominently features the Nationalist Party, transforming the ritual space into an indoctrination space.

Along the corridors, the maps of 26 battles from the late Qing era to the end of the Civil War establish a historical narrative that begins with Sun Yat-sen's successive rebellions at the turn of the century and ends with the battle between the Communists and the Nationalists on 23 August 1958 in the Taiwan Strait. Visitors walking along the corridors are also greeted with ten paintings commemorating the founding of the Revive China Society in 1894, the 1911 Yellow Flower Hill uprising, the victory against Chen Jiongming in 1917, the 1925 Battle of Huizhou (leading to the establishment of the Nationalist government in Guangzhou), the victory against Wu Peifu (1874–1939) in 1926, the victory against Sun Chuanfang (1885–1935) in 1927, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937, the shooting down of six Japanese airplanes by Nationalist forces on 14 August 1937, Chiang Kai-shek's drafting of 100,000 people into the military in October 1944, and the victory over the Japanese on 9 September 1945.

The hallways also contain two large reliefs of the 1925 Mianhu Battle, where the Huangpu Military Academy troops defeated Chen Jiongming, and the 1949 Battle of Guningtou, where the Nationalists succeeded in preventing the Communists from taking Kinmen (Jinmen, Quemoy) Island. The hallways are adorned with plaques, glass-encased memorabilia, and bronze head busts of notable martyrs, including anti-imperial revolutionaries such as Lin Juemin (1887–1911), a participant in the Yellow Flower Hill uprising, and Qiu Jin (1875–1907), a female martyr in the late Qing. Military figures of the 1940s have also been added. For instance, General Zhang Zizhong (1891–1940) of the National Revolutionary Army was killed in a battle against the Japanese Army in Hubei.Footnote 70 Qiu Qingquan (1902–1949) shot himself in the stomach when besieged by the Communists. Some of these martyrs are controversial figures. Liang Dunhou (1906–1949), also known as Liang Huazhi, set fire to a prison filled with Communist captives and committed suicide in Taiyuan, Shanxi.Footnote 71

Casual visitors are not allowed inside the great hall where the sacrificial rites take place. To the left of the great hall there is a spirit tablet of ‘the Yellow Emperor, the distant ancestor of the Chinese people’ (Zhonghua minzu yuanzu Huang Di zhi lingwei). To the right is a portrait of Sun Yat-sen, in his role as ‘the father of the nation’ (guofu). New presidents pay their respects to the Yellow Emperor on 5 April and to Sun Yat-sen at their inauguration.

At the centre of the great hall is located a sacrarium (shenkan), modelled after the one in the Shandong Temple of Confucius. In front of the sacrarium are a sacrificial offering counter and an incense burner bench. Chrysanthemums and miniature pines, both representing longevity, decorate the altar. Inside the sacrarium there is a large spirit tablet dedicated to ‘martyrs of the National Revolution’ (Guomin geming lieshi zhi lingwei) (see Figure 6).Footnote 72 This feature is based on the belief that the spirits of the dead inhabit spirit tablets and receive sacrificial offerings made to them. Spirit tablets used in making offerings to the dead were popularized and standardized by the Song Neo-Confucian Zhu Xi (1130–1200).Footnote 73

Figure 6. The spirit tablet of all who died for the National Revolution inside the Great Hall of the Martyrs’ Shrine. Source: Academia Historica, President Hsieh Tung-min (1908–2001) Archives, AH 009-030205-00013-010. Date: 29 March 1983.

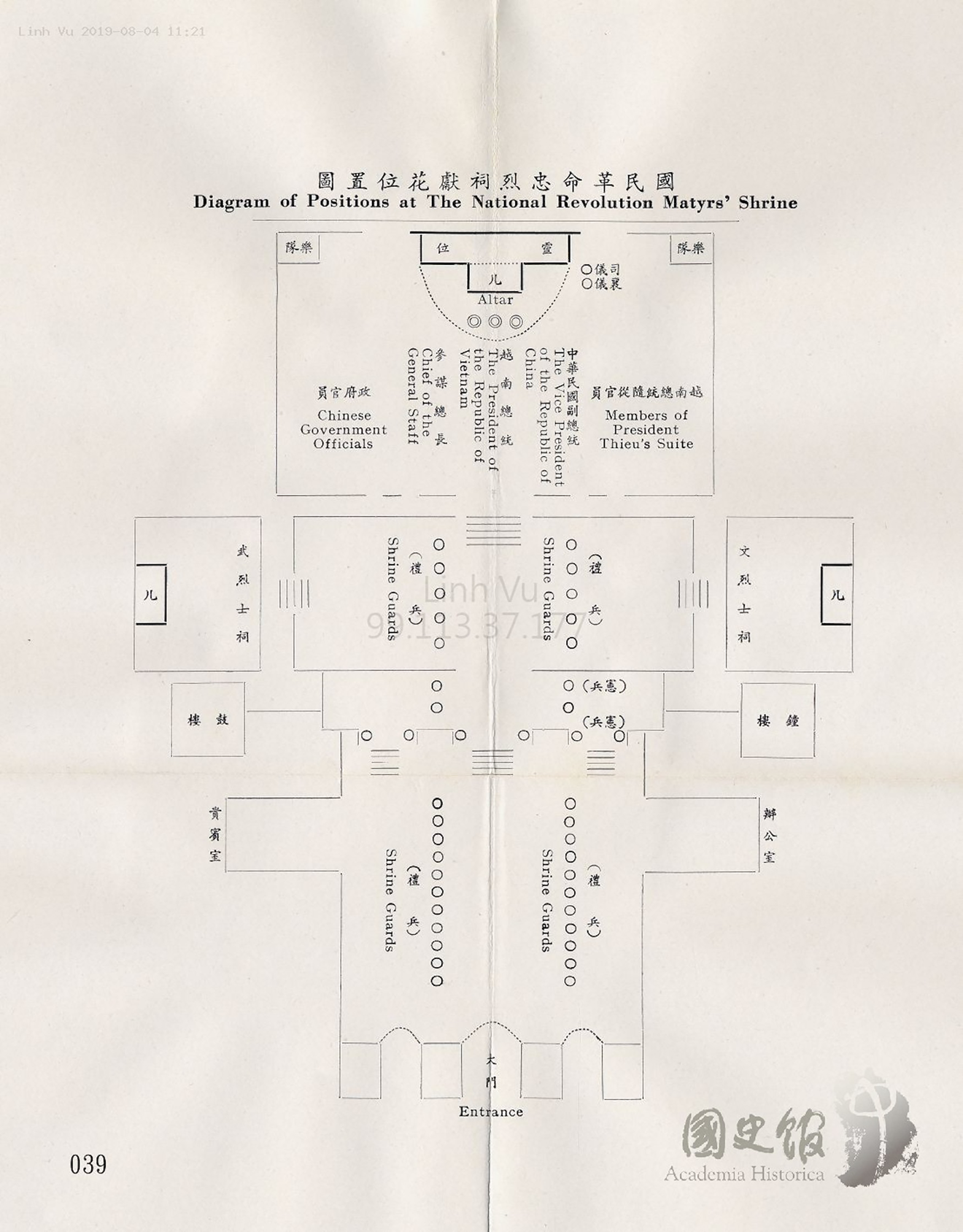

During the Cold War, a stop at the Loyal Martyrs’ Shrine was an essential part of the itineraries of visiting foreign officials from such countries as Bolivia, Dahomey (Benin), the Gambia, Iran, Italy, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Panama, Paraguay, the Philippines, South Vietnam, Spain, and the United States. Abiding by the one-China policy, the Nationalist Party strove to reinforce its claim of sovereignty over the Communist Party by having foreign diplomats ‘lay a flower wreath and pay homage’ (xianhua zhijing) to the Republican martyrs. According to the National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine Wreath-Laying Ceremony Guidelines in effect from 1966 to 1975, foreign dignitaries were met at the outer courtyard and escorted by honour guards. The visitors climbed up the stairs into the inner courtyard and entered the great hall. Once inside, the visiting head of state took his place at the centre facing the martyrs’ altar. An aide handed him a yellow flower wreath, which the official held aloft for a moment before handing it back to be placed on the altar. Taps were sounded while all the attendees stood in silence. After the ceremony concluded, the visitors were escorted back to the outer courtyard.Footnote 74 The visit lasted 15 minutes. The photograph in Figure 7 was taken during a visit by the first president of the Gambia Dawda Jawara in 1972. The honour guards hold guns with bayonets attached, highlighting the martial atmosphere of the shrine.

Figure 7. Vice-president Yen Chia-kan accompanying the first president of the Gambia Dawda Jawara to offer flowers to the martyrs at the National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine. Source: Academia Historica, President C. K. Yen Archives (CKY), AH 006-030204-00006-002-001. Date: 1972.

Initially, in this space dedicated to memorializing the patriarchal lineage of the nation, the first lady had no duties at the shrine and was not included in any ceremony. The wives of visiting foreign dignitaries appear to have been similarly excluded. A diagram from a visit by President Nguyen Van Thieu (1923–2001) in 1969 shows that he attended the ceremony at the shrine without his wife, who had accompanied him on the trip (see Figure 8).Footnote 75 In later decades, however, the spouses of foreign dignitaries were included in the ceremony, as seen in a visit by the president of the Republic of Honduras in 1991. President Rafael Callejas and the first lady were accompanied during the shrine visit by the vice-president, the chief of staff, and the minister of foreign affairs, and their wives.Footnote 76

Figure 8. Diagram of positions of dignitaries at the National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine for South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu's visit. Source: Academia Historica, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Archives, AH 020-100900-0154-0039. Date: 1969.

The shrine served as a funeral hall for Chiang Kai-shek's son and successor, Chiang Ching-kuo (1910–1988). His open casket lay in state at the Martyrs’ Shrine for a week before being transferred to his private temple in Cihu. During this time, the shrine was decorated with funerary yellow flowers, as well as crosses, for Chiang was a Baptist. Nuns and monks of various religious sects performed rituals. Groups of students, farmers, workers, and soldiers—people from all walks of life—and foreign dignitaries came to pay homage. Chiang's family members were in attendance, returning bows to mourners, following the traditional practice. Top leaders of the government and the National Party kept vigil as a sign of both loyalty and filiality.Footnote 77 From the 1950s to the 1980s, as these examples show, the shrine played ritual and diplomatic roles in bringing together domestic and international audiences.

Post-Cold War commemorative contention

In the decade following the end of the Cold War, major historical shifts demonstrated ‘how domestic politics and the politics of memory are intimately intertwined and shaped by global forces’.Footnote 78 The National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine (see Figure 9) began to find a new place in Taiwanese identity, which started to gain traction among the people on the island, and in ‘Taiwanese history’, which emerged as a discipline in the late 1980s and early 1990s.Footnote 79 In a way, the Martyrs’ Shrine transcends the island's colonial past. As the shrine had undergone complete renovation in the 1960s and incorporated martyrs from the Japanese colonial era, in the 1970s its origin as a Shintō shrine did not come into question during the post-martial law heritagization of Taiwan's colonial structures. Shintō shrines in Taoyuan and Miaoli counties which had been repurposed into Martyrs’ Shrines for Nationalist soldiers faced the prospect of being restored back to the original Japanese forms in the 1980s and 2000s respectively.Footnote 80

Figure 9. The Gate of the Taipei National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine. Source: Photograph by the author. Date: 10 June 2019.

In fact, even though the end of martial law in 1987 terminated the authoritarian rule of the Nationalist Party in Taiwan, the Martyrs’ Shrine continued its ritual function under the first Taiwan-born president, Lee Teng-hui (1923–2020), and under the first Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, Minjin dang) candidate to win the presidential election, Chen Shui-bian. The latter challenged many legacies of the Nationalist Party, for example, by renaming Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Square into Liberty Square in 2007 and removing hundreds of Chiang's statues from public areas. Despite Chen's effort to de-Sinicize and ‘de-Chiang-ify’ (qu Jiang hua) the island, he reportedly conducted the spring and autumn sacrifices at the shrine as prescribed by the previous leadership.Footnote 81 Although the Martyrs’ Shrine and its commemorative ceremonies were a Nationalist Party creation, they were embraced by the DPP leadership, albeit ambivalently. The shrine has become a national symbol that, to some extent, transcends contentious party politics.

During the presidency of the Nationalist Party candidate Ma Ying-jeou (2008–2016), the Taipei Martyrs’ Shrine received more political attention. In August 2014, an enshrinement ceremony was organized for the fallen Chinese soldiers in the Burma campaign of 1942–1943. The wooden tablet carrying the souls of over 56,000 Chinese expeditionary soldiers was transported from Myitkyina to Taipei by air and placed on the altar by the ceremonial guards. During the autumn sacrifice of 2014, Ma performed a lengthy service to honour the expeditionary soldiers from Burma after their spirits returned ‘home’. He reportedly became teary while watching a documentary about the repatriation of these loyal spirits. Descendants of the officers of the Burma Campaign attending the ceremony expressed their satisfaction that their relatives could now ‘forever enjoy the sacrificial offerings’.Footnote 82

Such comments are accentuated by news of the dedication of the honour guards who continue the ritual in all weather conditions. When a severe typhoon flooded Taipei in 2017, the guards reportedly remained at their posts and performed the ceremony as usual. They were photographed standing on their platforms, which had become islands in the middle of the rainwater ocean. In an interview, a guard stated that he valued the experience and had no fear of being swept away by the flood.Footnote 83 The reporter emphasized that such dedication stemmed from the respect that the guards, and by extension society, hold for the martyrs.

Although the second presidential victory of the DPP in 2016 led to controversy regarding the shrine's symbolic power, President Tsai Ing-wen has trodden cautiously around the issue. Contrary to her predecessor Ma Ying-jeou and the Nationalist Party, Tsai and her party take a strong stance on Taiwan independence and against the legacy of the Republic under the Chiangs. During her first year, Tsai demonstrated her standpoint by holding only a brief ceremony at the shrine. Even though previous presidents had spent half an hour offering flowers, burning incense, and reciting liturgical texts, Tsai simplified the ritual so that it took a mere six minutes. The president and the heads of five government branches did not sing the national anthem. Tsai also cancelled the ritual of ‘paying homage from afar’ (yaoji) to Sun Yat-sen's tomb in Nanjing during her swearing-in ceremony—a ritual performed by all previous presidents of the Republic of China, Taiwan.Footnote 84 She skipped the tribute ceremony to the Yellow Emperor, a precedent set by Ma Ying-jeou to construct the Sinitic origin of Taiwan.Footnote 85 After these instances in the news were negatively received by the public, Tsai allegedly performed the appropriate ritual during the autumn sacrifice of 2017.Footnote 86 During the spring sacrifice of 2018, she was also photographed consoling martyrs’ relatives and shaking hands with veterans.Footnote 87

Tsai's initial defiance at the Martyrs’ Shrine in 2016 was reinforced by a pro-Taiwan independence group that protested outside the shrine during her inaugural visit. The protestors urged her ‘not to follow in the steps of the authoritarian KMT [Nationalist] regime and lock the nation into a China-centred historical perspective’ and instead to convert the shrine into ‘a memorial hall commemorating Taiwanese who sacrificed their lives fighting foreign colonists’.Footnote 88 In response, Tsai expressed her intent to commemorate the White Terror victims who were slaughtered by the Nationalist government, announcing in her inauguration speech that she planned to set up a truth and reconciliation commission.Footnote 89 Following a clash between soldiers and demonstrators on 28 February 1947, a wave of protests and uprisings against the Nationalist Party-led regime had rippled through the island. From 1947 to 1987, tens of thousands of people were arrested, interrogated, jailed, and murdered by the authoritarian party-state for their real or alleged pro-communist, pro-Taiwan independence, and other political resistance viewpoints and activities. Under the pretext of national security, the government declared martial law in May 1949, stripping the general population of civil liberties and cloaking the island in terror. These four decades of White Terror were first acknowledged by President Lee Teng-hui.Footnote 90 In the late 1990s, the Taipei City Government constructed the 228 Peace Memorial Park from the Japanese-era New Park and converted a former radio station into a museum.

The White Terror victims, however, are not included in the Martyrs’ Shrine. Neither are the 200,000 Taiwanese men who ‘volunteered’ to fight for the Japanese empire, some of whom were sent to battles in Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands and never returned. As the Martyrs’ Shrine establishes the sacrifice of life to be the highest mark of citizenship, necrocitizenship—posthumous membership in the national community—is reserved for Nationalist stalwarts and those whose loyalty can be similarly construed.Footnote 91 Therefore, both the White Terror victims and the Taiwanese soldiers of the Japanese empire are excluded from this most exalted commemorative space and sequestered into different domains of remembrance. Such tension within the island memoryscape continues to haunt its people, despite the phenomenal transformation of collective memory since the turn of the twenty-first century. Those who perished for Japanese imperial ambitions and under the Nationalist reign of terror to certain extent constitute the limitations of the malleability of memories, and more critically, of necrogovernmentality—the state's response to past wars. Critiquing necrogovernmentality, Isaias Rojas-Perez, in his study of Peru's recent history, emphasizes how the post-conflict state, in its best interests, separates the present from a past wrecked by violence, narrows the possible legal and political options for victims and survivors to seek redress, and creates sanitized descriptions of wars.Footnote 92 Such attempts fail to satisfactorily bring closure to the people. Similarly, in the case of Taiwan, new generations continue to find gaps within the framework of necrogovernmentality to articulate their own projects of political reckoning.

Embodying the Nationalist ideology and the history of China, the Martyrs’ Shrine has lost some appeal on the island, while building a ‘transnational community of memory’.Footnote 93 The shrine is supported by many Chinese migrant organizations from the United States, Southeast Asia, and other parts of the world, by overseas branches of the Nationalist Party, and by veterans and martyrs’ relatives in mainland China. These people are tied to the past of Nationalist-ruled China. In addition, because anti-Japanese sentiment is not promoted by the Taiwanese government and is currently less prevalent on the island than it is on the mainland, many Japanese organizations and tourists pay their respects at the site where Nationalist generals who fought against the Japanese Imperial Army are enshrined.Footnote 94

The unique decolonization process in Taiwan, which Chang Lung-chih characterizes as ‘active reinterpretation and negotiation’, has contributed to the longevity of the Martyrs’ Shrine.Footnote 95 Chang argues that Taiwan's intellectuals and activists have not rejected all traces of the colonial era but have sought to transform former colonial sites into local cultural heritage.Footnote 96 Similarly, the Martyrs’ Shrine, as a relic of Nationalist authoritarian rule, has been transformed into a national heritage site in contemporary Taiwan. The adaptability of the Martyrs’ Shrine in the era of nationalism and multiculturalism is not unique when one considers the case of the Koxinga Shrine. Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong, 1624–1662), a Sino-Japanese pirate who took the Dutch Formosa as a base to fight the Manchus, is recognized as both a symbol of resistance against the Qing empire by Chinese Nationalists and as an embodiment of Taiwanese identity by advocates of Taiwan independence.Footnote 97 Koxinga is also elevated as a local hero in his Tainan base, as a paragon of Confucian loyalty for his anti-Manchu fight, and as a symbol of international relations as one who opened the island to the outside world and forged relations between Japan, China, the Netherlands, and Taiwan.Footnote 98 Likewise, the Taipei Martyrs’ Shrine is embraced for both its evocation of Taiwan's Sinitic characteristics and its accelerating cultural and political divergence from mainland China.

The diverse multitude of enshrined martyrs fits in with the multicultural push in the construction of Taiwanese identity in recent decades. Nonetheless, such a push is not without contention. Aboriginal cultures, along with historic imprints of Japanese colonialism, in particular Japanese architecture, previously repressed and destroyed under the Nationalist project of Sinicization, are preserved as cultural assets and promoted to national status. These Japanese traces, however, painfully remind the 1949 migrants who experienced the Second World War in China of the atrocities committed by the Japanese Army.Footnote 99

Within this context of conflicting memories, the Martyrs' Shrine continues its ritual function as an altar to Nationalist martyrs. In March 2019, two officers who died during the Second Sino-Japanese War were enshrined. Lieutenant-Colonel Bi Fuchang, a captain in the intelligence attachment of the Third Division of the Tenth Army, was killed in 1943 while leading an espionage unit during the battle against the Japanese Army in Deshan, Hunan. Major Liu Bingxun led an artillery battery in the Nanjing-Jiangning Fortress Command and perished during the battle in Tongshan, Jiangsu, in 1938.Footnote 100 Asserting Taiwan's version of the War of Resistance against Japan is crucial to the island's fight for autonomy, especially at a time when the Chinese Communist Party has been undervaluing the Nationalist regime's war effort.Footnote 101

Another notable case has been that of Zhao Zhongrong (1905–1951), an army commander who was arrested during the Chinese Civil War and subsequently executed in Beijing. After his daughter, Zhao Anna, spent two decades collecting evidence of his martyrdom and petitioning the Executive Yuan, Zhao Zhongrong was enshrined in 2018. In an interview in Taiwan, Zhao Anna, having returned from the United States for her father's canonization, expressed her contentment that her father's soul had finally been repatriated to his ‘old home’ (guxiang) and ‘fatherland’ (zuguo).Footnote 102 Ironically, both Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo, whose bodies have been placed in respective shrines in Taiwan, are still waiting to be reburied in their ancestral home in mainland China.Footnote 103 The notion of Taiwan as ‘home’ is deeply ambivalent.

Conclusion: The politics of death

‘It is also one of the peculiarities of the national phase of commemoration that it consistently preferred the dead to the living,’ wrote John R. Gillis.Footnote 104 As they became disenchanted with the modern world, the living started to haunt the dead by building their cemeteries, visiting their graves, and communicating with them through spirit mediums.Footnote 105 The dead never cease to matter because the nation, unlike the state, needs the dead to constitute its imagined community.Footnote 106 As the community shifts, the political afterlife of the dead is also transformed. All three elements can be seen in the case of Taiwan.

When the Republic of China was founded, the most celebrated deaths were those of young men who sought vengeance against the Qing authorities at the turn of the century. In the late 1920s, after the Nationalists established a relatively stable government in Nanjing, party members, soldiers, and other pro-state actors were also canonized. Those who had died in loyal service to the established authorities were extolled as the ideal martyrs of the 1940s. The Nationalist regime in Chongqing, the Japanese Imperial Army in China, the Nanjing collaborationist government, and the Communist regime in the northwest and central provinces also promoted a vision of martyrdom as a sacrifice for political ideologies. Martyrdom was equated with party-state loyalty, which served as the foundation of the Taipei National Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine. The shrine was an important component in the Nationalist leaders’ reinvention of themselves after their 1949 defeat through adopting the traditional aesthetic and by portraying China's soldiers and civilians as revolutionary, loyal, and morally superior.Footnote 107 In the 1970s, when the prospect of taking over the mainland was dimmer, the shrine came to affirm a divergence from the mainland by hosting new martyrs with ties to the island. During the Cold War, the shrine fulfilled its diplomatic duty as the physical manifestation of Chinese history and the Nationalist claim to Chinese territory.

The dead of the Republic of China have lost none of their significance over the last hundred years as various regimes have mobilized them to affirm their legitimacy. The shrine has witnessed the Nationalist Party's version of national history facing challenges from the new leadership and new generations of Taiwanese citizens. Nonetheless, it has found a new role in asserting Taiwan's political lineage. The DPP leadership has deemed part of the Nationalist historical narrative—the story of how the Republic struggled against imperialism, foreign invasion, and communism—suitable for claiming Taiwan's place in the contemporary world. As both a popular tourist spot and a national sacred site, the Martyrs’ Shrine participates in distinguishing Taiwan's cultural and political paths from China's.

Now that Taiwan has only a dwindling group of diplomatic allies left, the shrine may lose its ambassadorial role. The contemporary leaders of the island, however, are shrewdly emphasizing both Taiwanese identity and the Republican legacy to resist China's unification efforts. Nonetheless, the continual appropriation of the Martyrs’ Shrine, an institution fundamentally tied to the Nationalist Party and its origin in mainland China, gives life to the Civil War rhetoric of triumphal unification in the foreseeable future. This rhetoric is embraced by both People's Republic of China leaders and Taiwan's Nationalists while being spurned by DPP members who favour Taiwan independence.

Although the Nationalist exiles who arrived on the island at the end of the Civil War, their descendants, and the Chinese diaspora tend to favour unification, the growing majority of Taiwanese under 40 years old tend to reject the Nationalist authoritarian legacy and the island's links to China. Recent developments have fuelled strong sentiments against ties with China, such as the 2014 Sunflower Student Movement in Taiwan to oppose the encroachment of the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement and Chinese President Xi Jinping's 2019 interpretation of the 1992 Consensus as ‘one country, two systems’ for Taiwan. Moreover, the restriction of civil liberties and outright persecution of Uyghurs in Xinjiang and the corrosion of Hong Kong's legal and political autonomy further cause Taiwanese leaders and people to fear a possible merger with China.

‘Commemorations sanitize further the messy history lived by the actors,’ penned Michel-Rolph Trouillot.Footnote 108 Such messiness, coupled with an even messier contemporary politics and society, is changing the world of the dead. The canonized dead in Taipei Martyrs’ Shrines may be demobilizedFootnote 109 in the sense that their spirits are to be returned to their families or to mainland China where most of them were born. Currently, these enshrined dead, whose presence has acquired new significance in confirming the sovereignty of the island, are far from being decommissioned and are likely to share the holy space with new crops of martyrs whose values resonate with new Taiwanese generations. As the Chinese Civil War retreats further from collective memory and the Nationalist/Communist dichotomy holds less relevance for the future, the struggle against imperialism and authoritarianism, and for democracy and liberty at the turn of the twentieth century embodied by Zou Rong, Wu Yue, and the youth of the Yellow Flower Hill uprising and others remains powerful, perhaps enough to keep the Taipei Martyrs’ Shrine standing for longer. But one does not know for certain as Walter Benjamin's ‘angel of history' is propelled by the storm of progress into the future with his eyes towards the past.Footnote 110

Acknowledgements

The field research for this article is funded by the A. T. Steele Faculty Grant (2018) from the Centre for Asian Research at Arizona State University. The author would like to thank Jieun Kim, Ruth Rogaski, and the three anonymous reviewers of Modern Asian Studies for their careful reading of the manuscript at various stages and their valuable comments.

Competing interests

None.