Speaking at a Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) Officers conference in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1992, Vice President Dan Quayle emphasized the importance of personal responsibility, family values, and respect for the police in the crusade against drugs. “The ultimate weapon against drug and alcohol abuse is the commitment to values … values like faith, hard work, integrity, and personal responsibility,” he told the officers. Evil forces promoting drug use, such as pushers, media outlets glamorizing drugs, and rappers such as Ice-T, whose lyrics said “it's OK to kill cops,” were undermining traditional morality, belief in family values, and trust in police officers. And the nation's youth were most at risk of succumbing to such threats. But “that is where DARE comes in,” Quayle stated. “By teaching children how to recognize and resist peer pressure, by informing them about positive alternatives to drug use, by building their self-esteem, yes, DARE reinforces the importance of family values.” The Vice President commended the DARE officers for their vital contribution to the drug war, telling them that “together we will keep America great.”Footnote 1

As Quayle's discussion of family values, personal responsibility, and reverence for the police at a drug education conference suggested, the “drug crisis” constituted much more than drug use. Many policy makers and law enforcement officials mobilized fears about drugs to advance other political agendas. Within this context, the DARE program empowered the police to take responsibility for teaching kids important cultural lessons that often only tangentially addressed drug use. Indeed, the battle waged by police officers in the DARE classroom accomplished important political-cultural work during the Reagan era. Using police officers to deliver the DARE curriculum and its messages of personal responsibility, self-esteem, and support for law-and-order ignored the ways the “drug crisis” stemmed from material conditions and structural inequality. Ultimately, DARE bolstered the state's carceral approach to the drug problem.

Scholars concerned with the carceral state have frequently pointed to the war on drugs as a primary driver of punitive policies. But punitive policy was only one side of the drug war. Focusing solely on the mechanisms that produced larger prison populations fails to explain why punitive measures became widely accepted, and how law enforcement and “get-tough” logics extended to institutions outside the formal criminal legal system. Julilly Kohler-Hausmann and Elizabeth Hinton have certainly shown how urban and welfare policy “got tough” and became punitive in the 1970s and 1980s.Footnote 2 But the analysis remains confined to the ways in which policy makers applied punitive policy to new arenas, and misses how the police maneuvered to define social issues of drug use and poverty as law enforcement problems. Similarly, scholarship on police and schools has been largely contained within the school-to-prison pipeline framework that explains the expansion of police in schools as part of a punitive turn in school discipline policy.Footnote 3 Exploring DARE, in contrast, shows how the police presence in schools expanded not only from the extension of punitive policy to new arenas and the evolution of get-tough school discipline practices, but also from an educative and values-oriented project. The DARE officer helped normalize and legitimize the police as a feature of the school environment, and—alongside the “just say no” message—helped embed schools into the carceral state.

As a police-led drug education program, DARE developed broad-based appeal among policy makers, educators, and law enforcement, driving home the message that solving youth drug use was best left to law enforcement rather than social services or public health.Footnote 4 DARE was promoted as a nonpunitive and preventive program to help students resist drugs by learning how to say no, recognizing the consequences of their choices, and agreeing to the importance of personal responsibility and the moral values of right and wrong. But employing cops as teachers and promoting a zero-tolerance message tied drug education to a carceral frame. Indeed, DARE officials’ and policy makers’ use of the term “drug abuse” to describe any substance use whatsoever constituted a rejection of all alternative approaches to drug education, such as responsible use, and constituted a key part of the effort of drug warriors—ranging from law enforcement officials to Secretary of Education William Bennett to President Ronald Reagan—to insist that the only correct decision was to avoid drugs or face the consequences.Footnote 5 As a law enforcement initiative focused on “drug abuse,” DARE wedded the hard power of the drug war expressed through drug raids and arrests on the nation's streets to the soft power of prevention and education in the nation's schools. Additionally, despite the claims of proponents that the program was separate from law enforcement efforts to reduce the supply of drugs, DARE blurred the distinction between the supply and demand sides of the drug war.

DARE reached its height in the mid-1990s due to a concerted campaign by DARE officials, none more so than Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) chief of police Daryl Gates and commander Glenn Levant. Gates and Levant came up with the idea for DARE in 1983 and promoted the program to police departments across the country. They also worked with business leaders to establish a nonprofit organization called DARE America to facilitate fundraising and program expansion. Following the creation of DARE America, DARE's expansion rested on private donations, corporate sponsorship, and cultural cachet developed through sales of DARE paraphernalia and support from entertainers and athletes. As DARE gained national stature, the Reagan administration saw it as an opportunity to promote its messages of personal responsibility, family values, and respect for law and order by providing federal funding and rhetorical support.

Although evaluations of the program in the 1990s revealed that DARE was ineffective at preventing youth drug use, the program was successful at performing other significant work. DARE and drug education's popularity was never entirely about drugs, but part of broader debates about personal responsibility, family values, support for the police, and respect for law and order. The reinvention of the American family became a focal point of concern in the 1970s amidst sectoral shifts in the economy, the unmaking of the Fordist family wage, the fallout from Vietnam, and changing sexual and cultural norms.Footnote 6 Calls for parents and kids to rededicate themselves to family values and morality in drug education programming were intimately connected to such policies. Employing the DARE officer to deliver colorblind values lessons to students in the classroom and parents in targeted parenting sessions established the police as figures to shore up the nuclear family and enforce traditional discipline. These cops-as-teachers integrated such lessons into the state's disciplinary project.

Arresting the Demand for Drugs: The Origins of DARE

By the early 1980s, the LAPD had been engaged in a long-running war to address drug sales on Los Angeles public school campuses. In the 1970s, during an era of panic over youth crime, the department created a school-buy program in which undercover officers placed in high schools caught and arrested drug pushers. Starting in September 1974, eleven officers enrolled in twenty-four different Los Angeles–area high schools as undercover officers.Footnote 7 During its first year of operation, undercover officers arrested 211 drug dealers, 180 of them juveniles, and confiscated $20,700 worth of narcotics. Arrests and seizures only increased over the next decade as the Buy Team arrested 556 drug dealers and seized nearly $500 million worth of narcotics in 1982.Footnote 8

But drug use among school-age youth had also increased, at least according to law enforcement. One undercover officer reported in 1983 that 75–80 percent of Los Angeles high school students had used some form of narcotics at least once. More alarming for local officials, 40–50 percent used narcotics two to three times a week, and 15–20 percent were under the influence of drugs “most of the time.” Drug use had also filtered down to junior high and elementary schools, and some experts argued that kids as young as twelve used marijuana on a regular basis. Arresting drug dealers had done little to address the reasons why young people turned toward drugs in the first place.Footnote 9 The ineffectiveness of enforcement strategies to reduce the supply of drugs, police believed, had to be paired with stopping the demand.

Police department leadership recognized that enforcement measures had not only failed to stem the supply of drugs but had also done nothing to address the demand among the city's youth. Chief Gates, a strong proponent of an all-out attack on drug pushers and drug-related crime, emphasized the need for demand reduction. “It became obvious to the Department that conduct of the war locally against narcotics called for a new approach, one aimed directly at a new generation of potential users in the sound belief that once the market for controlled substances diminished, so would their availability,” Gates reported in 1983. “Demand always governs supply.”Footnote 10 The solution to youth drug use proposed by Gates, however, revealed how the police used the claim to be addressing demand through an educative—rather than enforcement—project that, in practice, blurred law enforcement's overly simplistic distinction between the supply and demand sides of the drug war.

Gates, building on Commander Glenn Levant's efforts to develop crime and drug prevention programs, approached the Los Angeles Unified School District's (LAUSD) Board of Education with a new idea. At a series of board meetings in the winter and spring of 1983, Gates described the escalating problem of drug use among the city's youth and the failure of the LAPD's School Buy program. Gates asked the Board members to cooperate in the development of a new program to teach children and their parents about the harmful effects of drugs as a means of decreasing the demand.Footnote 11 Working with Superintendent Harry Handler and health education specialist Dr. Ruth Rich, the LAPD and LAUSD proposed a drug education model to intervene in the lives of elementary school children before they were introduced to drugs. They called it Project DARE.Footnote 12

With Project DARE, school and police officials entered into a program of mutual cooperation. The joint agreement between the LAPD and LAUSD stated that “the program's objectives are to prevent and/or reduce substance abuse among school age children and youth.”Footnote 13 Students had to be taught to resist the temptation of drugs and the pressure from their peers, and to say “no.” DARE, Gates outlined in the LAPD's 1988 annual report, would reduce demand by teaching students “to resist peer pressure to experiment with drugs.” DARE was poised to fill this demand reduction role. As Gates concluded, “The true measure of DARE's worth is realized every time a child is confronted with peer pressure to try drugs … and that child says, ‘No.’”Footnote 14 Law enforcement believed saying “no” would address what they viewed as the underlying causes of drug use: the absence of personal responsibility, poor self-esteem, and bad choices. DARE would “attack the problem of drug-abuse through early educational intervention stressing value decisions, self-concept improvement and peer pressure resistance training.”Footnote 15

The educators and health professionals who designed the DARE curriculum—like the LAUSD's Ruth Rich, for example—intended it to be different from previous drug education programs. Fear-based drug prevention had clearly not worked, which led education and health specialists to develop new programs based on psychosocial approaches.Footnote 16 Rather than employing traditional strategies based on scare tactics that focused on the hazards of using drugs, such as negative health effects and addiction, DARE was billed as a positive program to shape youth behavior, enhance self-esteem, and resist peer pressure.Footnote 17 “We want to get away from the conventional use of the display board, which stresses recognition and identification of drugs,” explained Lt. Patrick Froehle of the LAPD Juvenile Division.Footnote 18

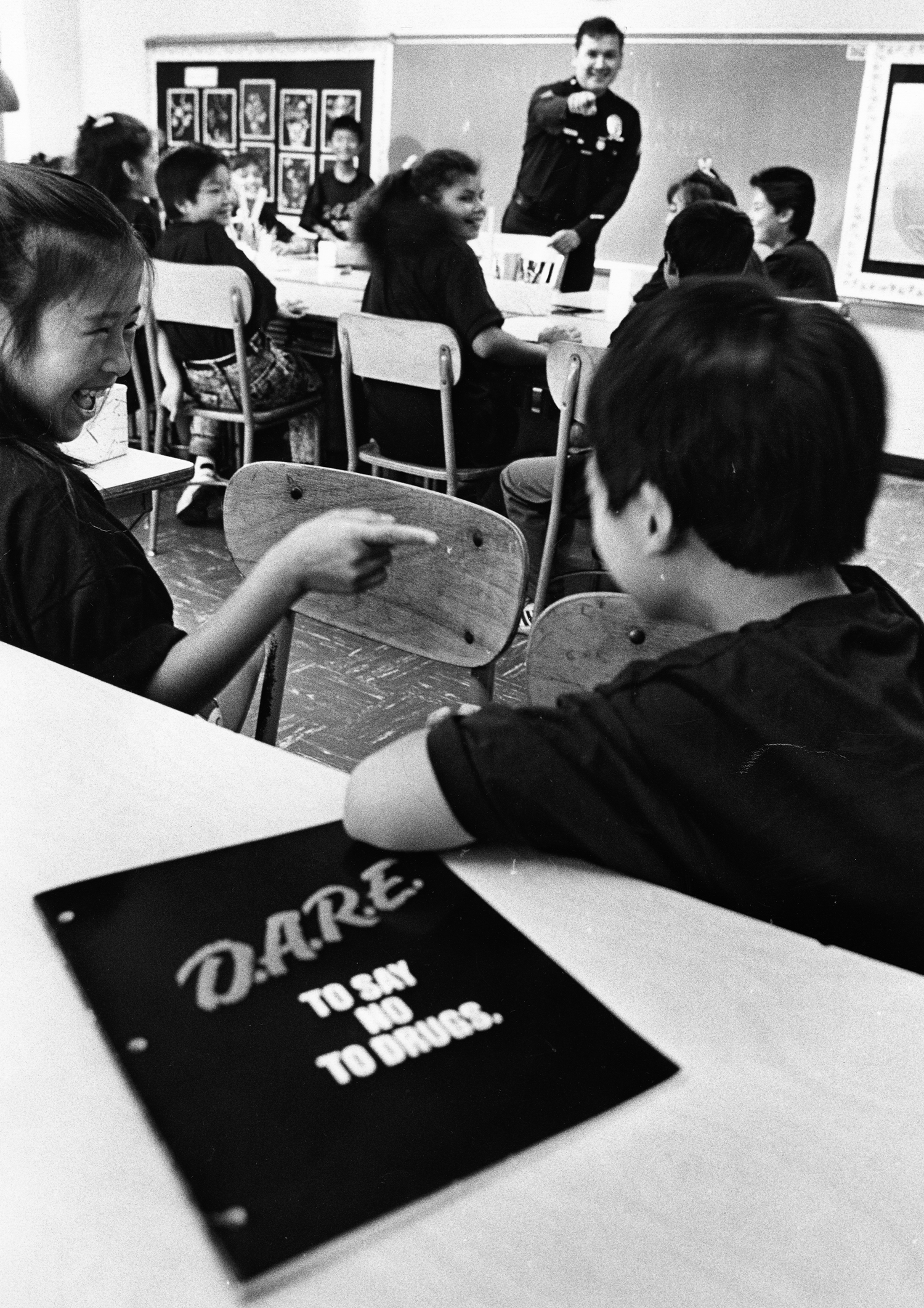

The focus on prevention education did not mean the police took a backseat to teachers. Rather, they became the teacher, guiding fifth-grade students through DARE's fifteen-lesson curriculum (later expanded to seventeen lessons and to junior high schools). In the first year, ten LAPD officers were assigned to a full-time classroom “beat”—notably adopting the parlance of a police officer's street “beat” to the classroom—with each officer responsible for instruction at five schools (Figure 1). Decreasing the demand for drugs required extending the authority of the police from crime-fighter to classroom educator. It marked a new departure for the police in the drug war. As LAUSD Superintendent Harry Handler suggested, “It also means a new approach by the police toward preventive action rather than just the enforcement of drug laws.”Footnote 19 DARE provided a ready-made example for policy makers, as well as a model program for local school districts and police across the country.

Figure 1. DARE session led by LAPD officer Gary Guevara. Dean Musgrove, Sept. 15, 1988, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, CA.

Focusing on the demand for drugs was not isolated from aggressive policing. The language of war inundated DARE's messaging. Its prominent focus on “arresting demand” relied on get-tough language, and Chief Gates often emphasized the LAPD's record of arresting drug dealers and confiscating narcotics in one moment, while lauding the department's role in pioneering the DARE program in the next.Footnote 20 “We must have short-range and long-range solutions,” Gates explained in the DARE Parents Guidebook, “from battering rams on ‘rock houses’ to immunization of our children through education.”Footnote 21 Law enforcement officials weaponized antidrug education by employing police officers as teachers and using the martial rhetoric of the war on drugs within the nation's elementary schools.

Proponents of DARE viewed police officers’ experience fighting the drug war on the streets as a key asset. Policy makers and program administrators described DARE officers as “patrol-hardened, veteran police” who would command respect from youth and “effectively shore up the classroom teacher's anti-drug education.”Footnote 22 Police officers, many proponents believed, had credibility as teachers because of their “street experience” and ability to recall “real-life” stories and examples of drug use from their time on the streets.Footnote 23 Indeed, law enforcement officials had concluded that elementary school students were so accustomed to seeing drugs that police officers were the only option for changing student attitudes. “Fifth- and sixth-graders in our society today, they know more about this whole (drug) issue than the vast majority of the teachers do,” Gates argued. “So the teachers are not in a position to do it. It's the police officers who are.”Footnote 24 Such attitudes facilitated the entry of police officers into schools and, by extension, reinforced the implicit message that punitive state power backed up the consequences for illicit drug use. Framed as drug war experts, the DARE officers replaced teachers in the classroom.

The police officers intended to enhance students’ reverence for the rule of law. Improving adherence to the law reinforced the focus on behavioral change and the production of disciplined, responsible citizens who saw the police holding back the forces of crime and disorder. As one section of the DARE student binder explained, “law” was a word all students should know and understand. The lesson went on to define law as “rules of conduct that are made by people elected to the government. Laws help people respect the rights of others. Laws are made to protect people and to keep them safe.”Footnote 25 This emphasis on respect for law aimed to create obedient kids and suggested that breaking the law came with consequences. Indeed, antidrug education focused as much on enhancing respect for law and order as it did on solving the problem of drug use among the nation's youth.Footnote 26

DARE's perceived ability to alter student perceptions of the police and to promote adherence to law and order appealed to the nation's drug warriors. Assistant Attorney General Jimmy Gurulé wrote to Attorney General William Barr in 1991 about the crucial role DARE played in reinforcing the law-and-order message of the police. “A very important part of this program,” Gurulé stated, “is to provide an environment in which children will develop a positive attitude toward law enforcement and, subsequently, will have a greater respect for our laws.”Footnote 27 Bringing police into schools, such officials hoped, would reorient students to accept the mission of law enforcement.

Operating within the context of the turn toward problem-oriented and community policing, improving police–community relations was a key component of DARE that often had little to do with preventing drug use. When New York City adopted the program in the mid-1990s, for instance, officials revealed DARE's central role in what amounted to a public relations campaign coming on the heels of a series of crises, including the Central Park Five case. “Forget about the drug education,” admitted Robert Strange, a former DEA agent who worked on antidrug initiatives for New York City. “We saw a relationship that could be built between the students and the police officers. There's no other vehicle for that that we're aware of.… For critics who say it's good PR for the police department, they're absolutely right and we should do more of it.”Footnote 28 DARE officers also reported that the program opened up new lines of communication with kids. “When I worked patrol,” a Michigan DARE officer explained, “I rarely said over a half a dozen words to kids, and they certainly had little to say to me. Now [after working in D.A.R.E.®] I talk to kids all the time—even ones who graduated from the program several years ago—and it's amazing some of the things they tell me.”Footnote 29

The pro-police image was imagined by DARE leaders to be especially beneficial for kids who had a historically antagonistic relationship with law enforcement. “After years of being the anonymous, uniformed ‘enemy,’ viewed with suspicion in some neighborhoods,” James Stewart of the National Institute of Justice reported, “it is gratifying and energizing for these officers that the children come to see them as positive role models who want to help them protect their future.” While not mentioning race, Stewart's reference to negative views of the police “in some neighborhoods” was no doubt a reference to the tension between African American communities and the police, which had accelerated following the urban uprisings of the 1960s.Footnote 30 These views of DARE's utility built on longstanding police–community relations projects aimed at kids in communities of color, such as police athletic leagues, officer friendly programs, and school presentations on the police role in government. But it also marked a departure. DARE officers were now part of the day-to-day life of students in and out of the classroom, and this aimed at naturalizing the presence of police in the lives of American youth.Footnote 31

Claims that DARE relied on a standardized curriculum did not mean that implementation of the program was the same across metropolitan space. DARE officers often engaged more directly with students in “urban” and “inner-city” schools—labels that enabled proponents of DARE to describe the program as race neutral while relying on the implicit racialized understandings of those terms. “At urban schools,” one study found, “D.A.R.E. officers tended to spend more time on the school grounds and typically interacted more with students outside the classroom, including the playground setting. In contrast, D.A.R.E. officers in suburban schools were quick to move on to another school.” As a result, students in “urban schools” had a greater “opportunity to ‘connect’ or ‘bond’ with the D.A.R.E. officer than did their suburban counterparts and to see them as part of the school environment.”Footnote 32 The different approach reinforced the message that communities of color required greater attitudinal shifts toward the police. Such efforts to present police officers as people rather than “robots or some untouchable force,” in the words of one DARE officer, were necessary because of the aggressive approach to the drug war, especially in low-income neighborhoods of color.Footnote 33

Evidence is scarce about how exactly DARE officers explained to schoolchildren the violence of policing, as are stories about students’ family members who may have been harassed or abused by the police. But DARE's emphasis on zero tolerance for drugs, and also its framing of drug use as an individual choice that came with consequences including arrest, imprisonment, and even death, were attempts to resolve the contradiction between the aggressive drug warrior on the streets and the friendly DARE officer in the classroom. DARE's message likely suggested to kids in heavily policed neighborhoods that people who used or pushed drugs, including their peers and family members, deserved the consequences of their choices.Footnote 34

Educators welcomed DARE officers as credible experts on drugs and antidrug education because the program socialized students to respect the police. Teachers and principals were some of the lustiest proponents for using uniformed officers as instructors. An interim evaluation of the program given to elementary school principals and teachers during the 1984–1985 school year found that both groups unanimously supported the method of program delivery using LAPD officers to provide instruction. In response to the question “Do you approve of the law enforcement personnel wearing uniforms while teaching?” teachers responded with 4.9 out of five while principals responded with five out of five.Footnote 35 Educator support seemed so widespread that one outside evaluation stated, “DARE has been overwhelmingly accepted and viewed as extremely valuable by school staff at both the elementary and junior high school levels.”Footnote 36 For some educators, the program had an even greater function because DARE officers were not only viewed as teachers but as representatives of law enforcement. The principal of McKinley Avenue School, in the predominantly Black neighborhood of South Central, commented: “Great public relations were fostered between the school children and the officer. And with our location in the (high crime) inner city, it was great having the officer on the school grounds for all-around purposes.”Footnote 37 The program's popularity with police and educators, then, took root in its perceived ability to address problems of police legitimacy among youth of color and to aid in suppressing crime more generally.

Alongside the pro-police message, initial evaluations of the program suggested that it helped prevent drug use. An evaluation conducted by the Evaluation and Training Institute (ETI) for the LAPD after DARE's first year in operation found that 96 percent of students gave the “preferred response” to questions about drug use, knowledge about drugs, views of the police, self-esteem, and peer pressure compared to 50 percent of non-DARE students. The ETI, which was contracted by the LAPD to conduct annual evaluations in the 1980s, repeatedly found the program to be successful based on annual evaluations showing students responding with the preferred no-use answer to drug use and positive attitudes toward the police. As the ETI found, “Not only did the students obviously become aware of and internalize their feelings regarding the topics taught in the curriculum but they also enjoyed using the materials and participating in role playing activities.”Footnote 38

Students often believed police officers to be credible deliverers of the antidrug message. Some independent evaluations of the program found students came out of DARE with more respect for police officers and found them more believable than their regular classroom teachers. One 1988 study from Kentucky concluded that DARE produced “strong positive increases in the attitudes of fifth grade students toward law enforcement.”Footnote 39 Meanwhile, the ETI found students wrote “thousands” of letters thanking “their” DARE officer and schools held special “appreciation days’ for officers.Footnote 40 Indeed, an ETI evaluation conducted between 1985 and 1989 found, “Non-DARE students are more likely to have stronger negative attitudes about law enforcement officers than DARE students.”Footnote 41 Students often related positive views of the police as well. One fifth grader in Salem, Oregon, who took DARE in 1999, for instance, explained that the ability of police officers to recall “real-life” experiences from the streets with the consequences of drug use persuaded her to stay away from drugs. “It's nice to have the police officer come because he's more experienced,” the student believed.Footnote 42

Not all student responses were positive. Some studies found that the use of police officers led to increased student animosity toward the police. One 1989 study of 400 “inner-city youth,” conducted in Nashville, Tennessee, for instance, found that “the attitudes of students became more negative toward the police as a consequence of the program.”Footnote 43 Some law enforcement officials and policy makers were similarly wary of the program's reliance on police officers as teachers. While supportive of DARE, Severin Sorenson of the National Association of Chiefs of Police suggested that “teachers should teach, and law enforcement officers should apply the law.”Footnote 44 Other studies also questioned whether DARE's underlying goal of promoting positive student–police interactions was as successful as proponents believed. For example, a study conducted by researchers in Kokomo, Indiana, found that “there was a sharp decline in positive attitudes towards the police.”Footnote 45 Despite this skepticism and a growing body of social scientific literature on DARE's limitations, the program continued to gain popularity.

As independent evaluators pointed out in the 1990s, early studies by the ETI finding DARE an effective tool were limited because ETI worked closely with the LAPD, and the studies were not longitudinal assessments of the program, nor were they based on randomized trials. Indeed, social science researchers would engage in a heated debate with DARE administrators, such as DARE America director Glenn Levant, during the 1990s regarding studies that found DARE to be ineffective at preventing drug use in the years after students completed the program.Footnote 46 However, despite the consensus that DARE remained ineffective at accomplishing its stated goal of reducing youth drug use, and despite some pushback from students and policy makers, the program accomplished other work for the police and policy makers. These stakeholders viewed DARE as a way to promote personal responsibility, family values, a privatized solution to government responsibility, and respect for the police.

DARE's Expansion, Corporate Sponsorship, and Political Support

DARE's initial success in Los Angeles brought national attention from law enforcement executives. James Stewart, executive director of the National Institute of Justice, was “very impressed” with DARE and called the program the only one of its kind.Footnote 47 Stewart followed such praise by sending DARE brochures to police departments and school districts nationwide, which encouraged other police departments to visit Los Angeles to learn about the program.Footnote 48 Aided by relatively small seed grants from the Department of Justice's Bureau of Justice Assistance to establish Regional Training Centers where police could be trained as DARE officers, DARE spread quickly.Footnote 49 By its ten-year anniversary, the program operated in 5,200 communities in all fifty states, and the Department of Defense had adopted the program for its schools in bases around the world. In 1993, more than 5.5 million children nationwide received the DARE curriculum.Footnote 50 Indeed, DARE became so popular with police departments and educators that by the mid-1990s, it was taught in over 70 percent of the nation's school districts and dozens of countries around the world.Footnote 51 DARE's significance, influence, and physical reach, while aided by federal antidrug funding, developed from administrators’ ability to enlist corporate donors, entertainment stars, and professional sports teams to market the program. This combination of forces not only brought DARE officers into classrooms but also into the nation's cultural consciousness.

Even as community policing gained adherents, especially in the 1990s after the Rodney King beating and President Bill Clinton's Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) program, local policy makers faced growing public pressure to put more police on the streets. Combined with shrinking municipal budgets in the 1980s, the emphasis on enforcing drug laws through arrest of pushers and users meant funds for crime prevention and community policing initiatives dried up. In response, law enforcement officials looked to the private sector to fund programs like DARE. But the turn to the private sector was more than a budgetary move. The reliance on corporate funding dovetailed with DARE's promotion of personal responsibility and self-esteem. Corporate sponsorship and the messages from celebrities supporting DARE reinforced the logic that drug use was rooted in the individual—not material conditions.Footnote 52

DARE administrators sought alternative sources of revenue to keep the program alive. Daryl Gates hoped partnerships with the private sector could expand the program. “Policing in the late 1980s and into the 1990s will be greatly different from the policing of two decades ago,” Gates explained in the FBI Bulletin. “One of the major differences, and an area of critical concern to police executives and managers, will be resolving demands for increased service within the constraints of reduced fiscal and personnel resources. Such prospects require today's managers to examine closely strategic alternatives to meet the demands that will be placed on their organizations.” To solve the budget crunch, the LAPD worked with local business leaders to create the Crime Prevention Advisory Council (CPAC).Footnote 53

The CPAC was essentially a fundraising arm for DARE. In an era of limited municipal budgets, the CPAC stepped in to support the police and, in the process, accelerated the privatization of public services. As Gates recognized, “The Crime Prevention Advisory Council is one example of how managers can ‘do more with less’ now and in the future.”Footnote 54 The CPAC often donated cash, vehicles, and other equipment for DARE's use.Footnote 55 DARE administrators suggested that the turn to private fundraising was a result of both the lack of public funding available for drug education and the importance of mobilizing the business community. “We have motivated the private sector in our city, and they have been overwhelmingly responsive to donating to this project and have really kept us afloat,” Officer Van Velzer told a congressional committee. “The only public moneys we have received is a grant from the State of California, and that is a seed grant. We have had to rely on the private sector, and without question we must mobilize the communities.”Footnote 56

The DARE model fit within the broader push by the Reagan administration to pursue privatization and nonprofit funding. While the administration continued to promote government intervention for policing and drug interdiction, when it came to antidrug education, the solution focused on developing business investment, philanthropic involvement, and private donations. As Reagan's first director of the Drug Abuse Policy Office Carlton Turner explained, comprehensive educational programs against drugs “can be best accomplished by the private sector” with rhetorical, but not financial, support from the administration.Footnote 57 Such thinking persisted even when Reagan and Congress supposedly prioritized prevention and education in the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which allocated just $200 million for drug education, compared to $1.1 billion for state and local law enforcement. Alongside Nancy Reagan's entrance into the drug war with her “Just Say No” campaign, drug prevention reflected the New Right's ideological political agenda by relying upon a privatized, decentralized, and individual solution.Footnote 58

Local DARE projects fit the Reagan administration's bill nicely because they often relied on fundraising and donations from local business and civic leaders. In Las Vegas, for example, the Junior League of Las Vegas partnered with the Clark County School District and Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department to bring DARE to the city's fifth- and sixth-grade classrooms. The Junior League, a nonprofit, community-based fundraising organization, provided DARE with startup funding, logistical support, and appealed to local businesses to support the program.Footnote 59 “If Project D.A.R.E. is to be retained and expanded,” the League exhorted, “a commitment from more that [sic] just the Jr. League will be needed. Any investment you make into this program will be an investment in our future citizens and leaders.”Footnote 60 Support from the League and fundraisers sponsored by local businesses, such as Ted Wiens Tire and Auto Centers, Haycock Distributing, and Bonanza Materials, allowed the local DARE project to expand to twenty-five schools and reach 6,500 students in Las Vegas by 1989.Footnote 61

No moment more reflected the reliance on fundraising and private support than when DARE America incorporated in 1987 as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit.Footnote 62 DARE America facilitated the expansion of the program, operating as a national clearinghouse for DARE programming, instructor training, curriculum development and copyright, and fundraising and sponsorship opportunities.Footnote 63 “The formation of DARE AMERICA is the first step toward making the DARE Program a part of every school's curriculum nationwide,” former LAPD commander and DARE America director Glenn Levant told Congress in 1988. DARE America, according to Levant, would be led by “nationally prominent business and community leaders,” such as real estate developer Nathan Shapell and philanthropist Armand Hammer, who would help DARE America “coordinate fund-raising and sponsorship opportunities on the national level.”Footnote 64

DARE America reflected and reinforced the turn toward corporate sponsorship and private funding of public goods. Nancy Reagan's Just Say No program had been developing corporate sponsors for years, most notably Proctor & Gamble, and DARE similarly hoped to attract corporate sponsors. Sponsoring DARE, program literature explained, was “an investment in protecting the health and potential of half a million students … an investment in the future of our next employees, neighbors and citizens … an investment in our own future.” While DARE stressed that kids should adhere to the “DARE to Say No” message, they simultaneously told business leaders and corporations that DARE was a “Blue Chip investment” and asked them to “DARE to Say Yes!”Footnote 65 And they did.

DARE America quickly brought on a number of corporate sponsors, including Arco, Bayliner, Coca-Cola Bottling Company, Herbalife, Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC), Kimberly-Clark, McDonalds, Packard Bell, and Warner Brothers. Pacific Security donated $1 million to DARE in 1989, including a $500,000 one-time cash contribution to support DARE America.Footnote 66 Corporate sponsorship became a key component of DARE in states across the country. Lockheed Martin, for instance, sponsored Idaho's 1996 DARE Day.Footnote 67 Nationally, KFC entered into a partnership with DARE America, becoming the organization's first national corporate sponsor. KFC enlisted actor Michael Warren, who played an African American police officer in the television series Hill Street Blues, as national chairman and established a toll-free hotline to help DARE children achieve a drug-free future.Footnote 68 Corporate donations and sponsorship created a “three-way partnership among law enforcement, education and the corporate community” vital to the program's expansion across the country.Footnote 69

DARE America also partnered with media firms in an effort to influence student attitudes through advertising, television, and cultural productions. They brought on Hanna-Barbera Productions, the creators of the Yogi Bear cartoon. Hanna-Barbera partnered with the LAPD and LAUSD to make Yogi Bear, known as “DARE Bear Yogi,” the program's official mascot and “spokesbear” (Figure 2). Cooperation with the production firm also led to the creation of educational comic books for DARE students, with a new character, Dr. Bearfacts, who served as “the resident authority on drug education at Yogi's home of Jellystone Park.” LAUSD Superintendent Leonard Britton commented: “With Yogi as spokesbear, D.A.R.E. and its anti-drug messages will help reach even more children, teachers, and parents. We expect D.A.R.E. Bear Yogi to add a lot of enthusiasm to the program, for adults as well as children … He has universal appeal.” Working with Hanna-Barbera went beyond support for DARE's educational mission. It was meant to shore up future corporate sponsorship. “With Hanna-Barbera behind us,” Gates stated, “we'll be more visible to civic leaders and potential corporate sponsors whose support is crucial to the continued growth of the D.A.R.E. program.”Footnote 70

Figure 2. Chief Daryl Gates and Yogi Bear press event. Chris Gulker, ca. Feb. 16, 1989, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, CA.

Drug warriors also enlisted athletes to promote the DARE and the “just say no” message in the wake of the death of Len Bias, the star University of Maryland basketball player and number one pick of the Boston Celtics, from a cocaine overdose in 1986. In Los Angeles, Capitol Records partnered with the Los Angeles Lakers in 1987 to produce an antidrug rap single, including a music video of Laker players rapping, entitled “Just Say No.” Laker coaches and players, such as Pat Riley, Magic Johnson, and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, became foot soldiers in the war on drugs by promoting the just-say-no message in the song. The Lakers single merged celebrity with support for law enforcement. Proceeds from the song benefitted the Forum Community Services, formed by the wives of the Lakers in 1984 to reach the children of Inglewood with educational and antidrug programs. Forum Community Services donated all the revenue from the song to help implement the DARE program in Inglewood schools.Footnote 71 Laker players also participated in annual rallies and antidrug walks, often organized by the wives of the Lakers, to raise funds for DARE.Footnote 72

By the late 1980s, DARE had gained national recognition as the country's preeminent drug education program. It took on greater symbolic significance when Reagan declared September 15, 1988, the first National DARE Day. The celebration of the drug education program became an annual tradition that continued through Barack Obama's presidency.Footnote 73 In proposing a National DARE Day, Congressional representatives praised the program as “one of several highly effective law enforcement drug abuse education programs targeted to preventing drug abuse among children.”Footnote 74 Alongside accolades from members of Congress, the Los Angeles program received high-profile visits from Nancy Reagan, Secretary of Education William Bennett, George H. W. Bush, and Princess Alexandra, the first cousin of Queen Elizabeth (Figure 3).Footnote 75

Figure 3. Nancy Reagan attends a DARE session at Rosewood Elementary School in Los Angeles. Paul Chinn, Feb. 11, 1987, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, CA.

DARE America officials pointed to corporate sponsorship and fundraising efforts to suggest that DARE was not a government program. DARE reportedly received three times as much corporate funding and twice as many individual donations than other drug prevention programs in 1995. As the Republicans in the 1990s pushed through budget cuts and President Bill Clinton attacked social welfare, DARE seemed designed to withstand the onslaught. “If federal funding were entirely eliminated tomorrow,” Glenn Levant claimed, “the program would survive.” Such assertions belied the large-scale government investment in the program, namely the support of local police departments that used public funds to divert officers to the program. As one journalist concluded, DARE was “fundamentally a government program.”Footnote 76 However, the image of DARE as entrepreneurial and corporate-funded benefitted DARE America during an era of assault on government services and emphasis on personal responsibility.

Personal Responsibility, Zero Tolerance, and Respect for Law and Order

Future citizens and good workers required kids who knew how to respect the police and take responsibility for their actions. The DARE approach focused on individual behavior, self-esteem, and resistance to peer pressure to create “attitudinal change” in students.Footnote 77 “The program will stress value decisions,” the LAPD and LAUSD explained in a grant application, “self-concept improvement and peer pressure resistance training for elementary school youth.”Footnote 78 Those “values decisions” did not allow for any drug or alcohol use whatsoever. “Its purpose,” chief Gates explained, was “to teach youngsters how to remain free of drug contamination; how to create a decent future for themselves.”Footnote 79

DARE bypassed the structural inequalities that influenced drug use. Its leaders assumed that kids merely needed to be taught—and could be taught in seventeen weeks—how to make correct moral choices. But the idea behind preventive education went a step further. It assumed that kids also needed to be told what the correct choice was: saying no. “A basic precept of the DARE program,” a Department of Justice Report summarized, “is that elementary school children lack sufficient social skills to resist peer pressure and say no to drugs.”Footnote 80 Within the structure of the zero tolerance for drug use and the use of police officers as educators, DARE intended to ensure that students never used drugs.

The DARE curriculum also foregrounded the consequences and risks of drug use. Its second lesson was meant to help “students understand that there are many consequences, both positive and negative, that result from using and choosing not to use drugs.”Footnote 81 In the classroom, DARE officers led students through a series of questions in their DARE binder worksheets where students listed three consequences for using alcohol and marijuana, and three consequences of choosing not to use alcohol and marijuana.Footnote 82 “If students are aware of those consequences,” the Bureau of Justice suggested, “they can make better informed decisions regarding their own behavior.”Footnote 83

The lesson suggested the negative effects of drug use for health and future success. For instance, a student in New York responded in their DARE workbook that the consequences of using marijuana included “you could die.”Footnote 84 Although not explicitly stated, the program's framework of zero tolerance rested on the assumption that drug use could lead not only to significant health risks, but also to legal consequences. In comments on the value of DARE, educators expressed support for how the program implicitly reinforced the lesson that arrest or incarceration was a potential consequence for drug use. As one educator in Nashville, Tennessee, praised DARE, “Yes, it gives the students a sense of awareness. Such as: what goes on if you are arrested for some type of disorderly behavior.” Or as another wrote, police were appropriate teachers “since it is a criminal offense to use illegal drugs.”Footnote 85

Antidrug education complemented the free market orthodoxy of choice, which assumed that all students had the ability make independent decisions without any recognition of how opportunity was structured by discriminatory housing policy, economic devastation, and policing. Prevention programs, none more so than DARE, promoted a message that if kids knew the potential negative consequences of their choices, which included legal, economic, and social repercussions, they could be influenced to engage in responsible behavior.Footnote 86 The California Commission on the Prevention of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, for instance, recommended that school boards throughout the state establish “clearly defined and communicated laws, policies, procedures, and sanctions related to alcohol and drug use on campus,” and that they develop cooperative efforts with parents who were expected to enforce such policies at home. The DARE curriculum reinforced such messages by including a dedicated week on teaching kids how to make decisions by “evaluating the consequences of different actions.” If kids chose to use drugs, following this logic and DARE's zero-tolerance message, they would face the enforcement of strict discipline codes related to the use, possession, and sale of substances on school grounds.Footnote 87

Educators often made comments that revealed the interlocking nature of personal responsibility and discipline. Students, evaluators found, had become more respectful of the police, exhibited better behavior in school, and showed better self-esteem. But achieving the preferred just-say-no response from students regarding drug use was not the only measure of success. They also noted that students “are taking more responsibility for their actions.”Footnote 88 The soft arm of the drug war thereby legitimized punishment for making the “wrong” choices and reinforced a belief that the solution to the drug crisis was one of personal responsibility.

Emphasizing moral choices and personal responsibility contributed to a broader effort to produce model citizens. “D.A.R.E.® opens the door to young people to lay the foundation of responsible citizenship,” criminologist David Carter noted in an analysis of DARE and community policing. Contact with law enforcement was key to developing the characteristics of good citizens. “Constant positive exposure to a police officer over a sustained period of time can shape a positive attitude toward the community, its values, and the police,” Carter suggested, “consequently, D.A.R.E.® can help develop good citizenship in the students who participate.”Footnote 89 DARE officers reinforced this message in the classroom, suggesting that America's future was at stake. “If we are going to save our country, and I sincerely believe we are, DARE is but a start of getting communities and parents back together with our most vital element, our children,” one DARE officer told a congressional committee. “Forming them into positive, responsible citizens for our future.”Footnote 90

DARE told kids to take greater personal responsibility, or to face the consequences of arrest, incarceration, or, in some cases, death, which fit neatly within the Reagan administration's framing of drug use as a both a moral and law enforcement issue. If students made the wrong choice—to use drugs—the police were there to ensure they understood the potential consequences. Students had to recognize that drug use was a choice of the individual and could not be solved through social spending. The first step, as Reagan explained in the summer of 1986, “is making certain that individual drug users and everyone else understand that in a free society we're all accountable for our actions. If this problem is to be solved, drug users can no longer excuse themselves by blaming society. As individuals, they're responsible.”Footnote 91

DARE's message of personal responsibility and self-esteem was readily picked up by the administration and further disseminated in connection with zero-tolerance policies. Reagan administration officials, such as Secretary of Education William Bennett, pointed to moral education as the drug war's silver bullet. Bennett routinely linked values education to get-tough disciplinary policies. Nowhere did Bennett lay out his vision of education and enforcement more explicitly than in the 1986 Department of Education report What Works: Schools Without Drugs, which framed the solution to drug use as a combination of values education, get-tough policies, and personal responsibility. “Each of us must work to see that drug use is not tolerated in our homes, in our schools, or in our communities,” the report summarized. “Because of drugs, children are failing, suffering, and dying. We have to get tough and we have to do it now.” Following such logic, it was no accident that Bennett highlighted DARE as an exemplary program in What Works.Footnote 92

In turn, DARE organizers drew explicitly on Bennett's connection—articulated in What Works—between moral education and zero tolerance. Referring to the “poignant commentary made by William Bennett,” DARE administrators noted that such “get tough” rhetoric “echoes the sentiments of parents, educators and law enforcement professionals in conveying the urgency of the drug abuse problem, including distribution of drugs by gang members.”Footnote 93 LAPD officials often echoed such themes of personal responsibility, morality, and getting tough when describing DARE's utility. Deputy Chief Robert Vernon, an evangelical Christian, explained the importance of DARE's values education to the National Association of Evangelicals Convention in 1985 after a long introduction on the problem of gang violence and drug trafficking in Los Angeles:

We have young people today that don't understand why certain things are wrong. They just don't understand…. We need to have values education.… We have a program in Los Angeles we call DARE.… And part of the program is educating them as to why they should not use drugs.… You know, the thing about values, and the concept of right and wrong, the issue is here, it takes a lot of time. It doesn't take one class, we have to be in that school all semester in order to get across the point.Footnote 94

DARE proponents reinforced these messages by having students sign no-use pledges in DARE classrooms and write personal essays upon completing DARE, in which they pledged to remain drug free for life. The message was also meant to be carried into the future, as DARE administrators sealed antidrug messages from students across the country in a time capsule to celebrate the first National DARE Day in 1988.Footnote 95

Making any level of drug use unacceptable reinforced the emphasis on zero tolerance and personal responsibility. As one group of police scholars suggested in 1990, “DARE is the thin blue line operating at a moral level.” DARE's prevention message—to say “no” when offered drugs and to “never” use drugs—treated all drugs as equally dangerous.Footnote 96 Along with DARE, schools implemented a variety of antidrug activities aimed at changing attitudes and creating a culture of no use, such as the Red Ribbon Campaigns, where students pledged to not use drugs and participated in a Red-Ribbon Run.Footnote 97 The multipronged antidrug education programming not only denied the structural roots of the drug crisis, but also threatened punishment for stepping out of line and choosing to use drugs. Crucially, it also sent the message that the blame for irresponsible behavior was entirely the individual's and any consequences were justly deserved.Footnote 98

DARE, in effect, deputized students to alert the police of friends and family members who engaged in drug use. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, examples of DARE students turning in their own parents to the police for drug use became national news.Footnote 99 As Jimmie Reeves and Richard Campbell suggested in their study of media coverage of the crack epidemic, DARE put “uniformed police in the elementary classroom and encourages students to not only just say ‘no,’ but to snitch on those who dare to say ‘yes.’”Footnote 100

Relying on the police to disseminate messages of zero tolerance and personal responsibility also promoted a vision of disciplined citizens. Moral strength, choice, and individual responsibility made up the definition of a good citizen, and one uttered by DARE officers in classrooms across the nation and all the way to the Oval Office. As DARE America director Glenn Levant made clear, DARE's success was evident during the 1992 Los Angeles rebellion when, “We saw kids in DARE shirts walking the streets with their parents, hand-in-hand, as if to say I'm a good citizen, I'm not going to participate in the looting.”Footnote 101

Family Values, the “Inner-City,” and Race

DARE presented itself as a color-blind approach that applied to students of all races and ethnicities, and in all types of schools—urban, suburban, and rural. Policy makers at the local, state, and federal levels routinely emphasized how drug use was a problem of lost morality and the crisis in family values that impacted all youth regardless of race, ethnicity, or class. When he envisioned DARE, Daryl Gates believed that the threat of drugs in Los Angeles resulted from “the failure of family and other social institutions to teach the young proper values.”Footnote 102 Strengthening the nuclear family became a central goal of the program, as administrators sought to deputize parents to take responsibility for helping their children say no to drugs when not in school. In the process, DARE administrators relied on and reinforced racialized assumptions of the crisis in family values produced and disseminated by media outlets, sociological studies of the urban “underclass,” and the coded language of the “inner city” that pointed to the broken Black family as the source of the “drug crisis.”Footnote 103

Schools and the police thereby provided two prongs in what was a three-pronged approach to drug prevention. The third element was parents. DARE not only incorporated implicit messages about family responsibility in the classroom but also through police officer meetings with parents and community groups.Footnote 104 DARE leaders placed the program at the center of a triad linking school, police, andarents together. “The Los Angeles Police Department and The Los Angeles Unified School District are but two members of the partnership needed to help D.A.R.E. achieve its promise,” Gates introduced in the DARE America Parents Guidebook. “The other, and most important partners in this effort are the children's parents. All of us, working together, can save this nation's most vital resource, our children.”Footnote 105 Every DARE officer, for example, conducted at least one parent education session each semester for every DARE school. While the sessions focused on prevention strategies and encouraged family communication, they also stressed “parenting skills.” “Parent education sessions, as presented by DARE Instructors, provide parents with information regarding drug recognition, physical symptoms of drug usage, and behavioral changes from drug usage,” one DARE grant application summarized. “Additionally, parenting skills to increase awareness of strategies for improving family communications are provided.”Footnote 106 By 1986, DARE officers had reached nearly 50,000 parents in Los Angeles, where officers taught them ways to get “them involved in their child's life.”Footnote 107 In presuming to promote parenting skills, DARE reinforced the promotion of family values as the solution to drug use instead of new social and economic policies.

The emphasis on parental involvement and responsibility expanded over time. With assistance from the Bureau of Justice Assistance, law enforcement officials in Illinois and North Carolina created the DARE Parent Program (DPP). The DPP brought parents more directly into the DARE program by having police officers teach parents how to tell if their kids were using drugs, as well as to teach them proper parenting skills.Footnote 108 The parent program quickly became an institutionalized part of DARE. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, DARE staff produced a variety of parent program materials meant to engage parents in DARE and the antidrug message. Beginning in 1989, for instance, DARE partnered with the USC School of Cinematography to create a parent video, which “will illustrate positive parenting skills and demonstrate their application in vignettes showing ‘how to’ and ‘how not to’ deal with the child at various stages of development.”Footnote 109 Such messaging expanded when DARE America Executive Director Glenn Levant wrote a book for parents, entitled Keeping Kids Drug Free: D.A.R.E. Parent's Guide in 1998. “The goal of D.A.R.E.—the mission of this book—is to create a generation of young people who choose not to smoke, drink, or take drugs during their childhood and adolescence,” Levant summarized. “As adults, they will make decisions and live with the consequences. As children, they need your time, your guidance, your understanding and your love—now. Good luck.” Parents had to reinforce messages of personal responsibility by teaching their kids correct morals and values. But the message of responsibility also extended to parents themselves. As Levant instructed, “You must take responsibility for learning to recognize the signs and symptoms that your child may be abusing drugs and alcohol, involved with gangs, or participating in other illegal activities, and you must deal with these problems as soon as possible.”Footnote 110

While some parents opposed DARE due its potential to turn kids into spies for the police who would turn their own parents in for drug use, many parents responded positively to the message of family values and responsibility.Footnote 111 Many studies found parents supportive of the DARE program, responded to calls for them to take responsibility, and wanted to learn what they could do to help their children avoid drugs. Annual evaluations of the program found that parents who attended DARE Parent Meetings learned about the problem of youth drug use and what they could do about it. As the ETI found in 1985, parents “think it is a good idea to have uniformed police officers teaching about drugs.”Footnote 112 Such parental support was crucial to the larger political-cultural work the program accomplished for those law enforcement officials and policy makers who, in DARE, saw the opportunity to shore up the nuclear family and values.

Lessons about family values and parental responsibility played into the racist tropes of the broken Black family that accelerated during the Reagan era. Congressmen routinely brought up the problem of absent fathers as a root of child misbehavior and drug use. In a not-so-veiled statement about the Black family, congressman Mark Souder (R-IN) explained while questioning DARE ambassador and boxer Sugar Ray Leonard in a 1998 congressional hearing:

The point of D.A.R.E. and a lot of these programs and school teachers and coaches is that without a dad there, particularly, young boys, which is increasingly a focal problem that we have in our society are young boys who don't have dad impacting in their lives, they are more likely to be looking for some other role model because they don't see a male model in front of them.… If it's a drug dealer who has a big car, that's the danger and we're trying to counter-balance that.Footnote 113

DARE, as Souder implied, aimed to address this problem by reinforcing the nuclear family and family values, especially in communities of color.

Law enforcement officials also deployed DARE to promote the vision of the nuclear family and played on racialized descriptions of family breakdown. For instance, after an introductory description of gang violence in Los Angeles focused entirely on African American neighborhoods in South Central, a MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour report turned to LAPD deputy chief Robert Vernon to describe how police in Los Angeles responded such problems. Vernon placed DARE and its lessons about family values at the center of the solution to gangs and drugs:

I think the root cause here is the emphasis of the important role of parenting. I really think we need to get back to that.… However, the police department here in Los Angeles under my boss's direction have instituted a program called DARE … This year all of our elementary schools in Los Angeles have police officers in there teaching these important values.Footnote 114

Such political constructions of the drug and gang crisis as the product of disorganized, immoral Black families also fed into fears of the inner city infiltrating predominantly white suburban enclaves. In another speech, Vernon singled out “powerful drug trafficking organizations” in “inner cities” as the root of the problem that DARE attempted to redress. He went on to explain, “there's a lot of bloodshed occurring in our inner cities. Once again, remember, as goes the cities so goes the nation. We can't isolate ourselves and say well that's a problem of the inner city let's don't worry let's just contain it there.”Footnote 115 Suggesting that the problem of drug use and gang violence might infiltrate the suburbs, Vernon and other officials capitalized on the fear of the racialized inner city to expand both policing and prevention projects in all schools. Even as DARE entered school districts across the country, it played on panics about inner-city crack use and the breakdown of the Black family to garner more resources, expand the carceral state, and send an implicit message about a culture of poverty plaguing inner-city communities.Footnote 116

Framing the potential for drug use to spread to the suburbs from inner cities and ghettos reinforced the politically constructed dichotomy of the violent drug dealer and innocent suburban youth. DARE officials often employed the description of innocent white suburban families who had no reason to believe their kids would use drugs to promote the benefits of the DARE message. “This does not just happen in ghettos or inner cities. It does not just happen to poor kids or kids from broken homes,” Glenn Levant wrote in Keeping Kids Drug Free. “It happens everywhere in America to families in circumstances exactly like your own and to kids of every age, gender, race, and social class.” But the coded message was also that white suburban parents had more to fear, and to lose. “Discovering that your preteen uses drugs is a tremendous jolt to any parent,” Levant continued, “but particularly to a mom and dad who had no reason to believe they might have to face this problem.” Levant followed this assertion with a story of “Patti and Al,” a typical suburban couple who were shocked to learn their nine-year-old daughter, Meredith, had a friend who proposed trying her mother's marijuana. Luckily, Levant noted, their eleven-year-old son, Lee, had received a visit from a DARE officer in school and imparted some of DARE's lessons to his younger sister who returned home. “They never considered that drugs existed in their community because they lived in a nice neighborhood in the suburbs and all the children went to a ‘good school.’”Footnote 117

DARE's emphasis on parental responsibility and family values reinforced the Reagan and Bush administrations’ race-based attacks on the Black family and welfare recipients. No one reflected the ways that policy makers deployed coded language about the problem of a breakdown in family and moral values more than former Secretary of Education and drug czar William Bennett. Speaking to the Houston Area Urban League in 1989, Bennett described the problem of drug use not as one related to poverty, joblessness, or racism, but as one rooted in family, values, and personal responsibility—the same themes so often used to browbeat African Americans for continued inequality. “At the very time when we need to affirm things like individual responsibility, civic duty, and obligations to parents and to God, too many segments of society are equivocating and sending mixed messages,” Bennett exhorted the League. “This sort of moral enervation must be renounced in the strongest terms.”Footnote 118

The DARE officer was on the front line combatting the breakdown in morality and family values. As President George H. W. Bush told DARE representatives upon signing the national DARE Day proclamation in 1989, “Because perhaps no one has manned more front lines than the hundreds of dedicated Americans who form the ranks of D.A.R.E.—Drug Abuse Resistance Education. You talk of values and we heard that here today—of right and wrong, and teach kids to do good and reject evil, by avoiding drugs and by, then, opposing drugs.”Footnote 119 Vice President Quayle, as his speech to DARE officers at the start of this article demonstrates, reinforced the message.

Meanwhile, after Bush's lone term, Clinton continued to praise DARE officers for showing parents the way to combat drugs. “Parents have to recognize that the real war on crime begins at home,” Clinton emphasized in a speech to the International Association of the Chiefs of Police in 1994. “If the first responsibility of the government is to provide law and order, then the first responsibility of parents is to teach right from wrong.… We've got to have more folks helping them, like those wonderful police officers in the DARE programs all across America.”Footnote 120 First Lady Hillary Clinton reinforced the president's message. Speaking at a DARE event at Mott Elementary School in Flint, Michigan, on October 8, 1996, Hillary Clinton lauded the program. “The battle against drugs is going to be fought in the family rooms and the classrooms of America,” she told the audience. “We need D.A.R.E. and other community-based drug prevention programs like it to win this battle.”Footnote 121 Police officers were not only brought into schools as authorities on drug education, but also into the family as experts on parenting.

Combined with the zero-tolerance orthodoxy of drug warriors, DARE's moralizing messages legitimized punishment for those kids who did not live up to the standards of responsible citizenship, as well as punishment for their parents, implicitly from inner-city communities of color, who threatened the sanctity of the imagined nuclear family. Touting the DARE officer as the appropriate instructor on family values allowed the program's proponents and drug war policy makers to privatize the drug war. It would be won not through government investment in social policy, but by youth altering their behavior under the threat of arrest and incarceration.

Conclusion

The DARE program expanded the reach and ability of the police to define the parameters of the drug war during the 1980s and 1990s. Alongside the growth of punitive policies, mandatory minimum sentencing, and police on the streets, DARE brought uniformed police officers into schools as both educational authorities and symbols of the law-and-order message. For law enforcement, DARE provided a means to soften the image of the police forces that had otherwise aggressively pursued scorched-earth policies in communities of color in the name of the drug war. For politicians, on the other hand, support for DARE and antidrug education allowed them to appear as both pro-police and pro-kid while absolving the federal government of responsibility for robust social policy. Venerating the DARE officer solidified the drug crisis as a problem to be solved by law enforcement rather than social policy or public health experts.

Relying on the police to teach messages of zero tolerance, personal responsibility, family values, and respect for law and order also accomplished political-cultural work for policy makers and law enforcement. Most importantly, it diverted attention from the violent reality of the drug war. While the police may have softened their image and worked to improve perceptions of the police among kids and teenagers, the major emphasis of the police in the war on drugs centered on mass arrest and punishment, especially in and around predominantly Black and Brown schools. In addition, praise for programs like DARE and the broader message of drug prevention education never relied on evidence that such programs actually prevented drug use. While evaluations of DARE conducted in the early 1990s suggested that the program had not worked that well, viewed through a different lens the program was a success. By bringing police into schools to teach morality, family values, personal responsibility, and respect for law and order, DARE helped legitimate get-tough policies and an expanded police presence in schools.

Finally, the history of DARE and the soft arm of the drug war reveal the ways such programs operated on ideological foundations that ignored the structural roots of the drug crisis. The program's orientation reinforced the turn toward blaming the problem on drug users themselves and framing solutions rooted in individual behavior, family values, and morality. By using police officers as teachers, in turn, DARE further blurred the distinction between reducing supply by arresting pushers and demand through prevention. Viewed in this light, DARE was part of a punitive continuum that linked drug education to punishment, policing, and incarceration. Together they reinforced and defined governing logics focused on getting tough and extended the police into every facet of daily life.