INTRODUCTION

With the acceleration of globalization, its influence has been widely explored in various fields of international business research. The impact of globalization has long been examined around the convergence and divergence debate (Webber, Reference Webber1969): whether globalization accelerates the convergence of economic, political, and sociocultural aspects around the world, leading to the erosion of national differences across borders (Levitt, Reference Levitt1983) or the differences among countries, cultures, and societies remain, not being greatly attenuated by globalization (Ghemawat, Reference Ghemawat2007). Recently, the crossvergence concept has emerged in this debate, proposing business ideology influences that lead to convergence and sociocultural influences that lead to divergence will interact synergistically with one another and result in a unique value system different from both the convergence and divergence positions (Ralston, Reference Ralston2008; Ralston, Holt, Terpstra, & Kai-Cheng, Reference Ralston, Holt, Terpstra and Kai-Cheng1997). This debate raises an important question for international business ethics as to whether globalization leads to convergence, divergence, or crossvergence in business ethics in various national contexts (Robertson, Ralston, & Crittenden, Reference Robertson, Ralston and Crittenden2012).

A body of literature has focused on the conditions of divergence in international business ethics. Business activities and management principles perceived as ethical or unethical vary across cultures because national cultures strongly influence an individual's moral philosophies and value systems underlying ethical judgments (Christie, Kwon, Stoeberl, & Baumhart, Reference Christie, Kwon, Stoeberl and Baumhart2003; Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1992; Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Holt, Terpstra and Kai-Cheng1997). On the other hand, some scholars have stressed the view of convergence. In some situations, basic morality remains the same across national cultures, and there is more commonality in ethical values and principles across societies than commonly anticipated (Bailey & Spicer, Reference Bailey and Spicer2007; DeGeorge, Reference DeGeorge1993). Researchers also highlighted that culture evolves over time, and so do ethical values and principles in a society. Unique business ethics in a specific cultural setting at a specific time may not remain the same but become similar to those of other cultural settings over time, particularly with increasing cross-cultural interactions (Svensson & Wood, Reference Svensson and Wood2003).

As globalization continues apace and the importance of business ethics increases, whether cross-cultural differences in business ethics remain the same or widen or shrink over time has become a more critical question for managers conducting business across borders. However, little research has investigated whether national culture still functions as a key source of an individual's ethical standards and principles, and if so, when it happens. In a globalized marketplace, individuals’ national culture may still be a strong predictor of their ethical attitudes and behaviors in some situations, but it may prove to be of little significance in other circumstances in which members of different cultures and societies share common morality and beliefs (Bailey & Spicer, Reference Bailey and Spicer2007) or adopt new ‘crossvergent’ values shaped by various types (i.e., global, local, macro, and micro) of institutional pressures (Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Holt, Terpstra and Kai-Cheng1997). Although the literature has recognized that cross-cultural differences exist in the moral philosophy and ethical decision-making of business managers (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Kwon, Stoeberl and Baumhart2003; Fritzsche, Huo, Sugai, Tsai, Kim, & Becker, Reference Fritzsche, Huo, Sugai, Tsai, Kim and Becker1995) and that culture and predominant values in a society may evolve in relation to the degree of globalization engagement (Ralston, Pounder, Lo, Wong, Egri, & Stauffer, Reference Ralston, Pounder, Lo, Wong, Egri and Stauffer2006), little is known about longitudinal changes in cross-cultural differences in business ethics that might have occurred over time.

This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the evolution of business ethics in China and the US between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s. We build on three perspectives of value evolution, namely, convergence, divergence, and crossvergence (Ralston, Reference Ralston2008) to examine whether and how managerial ethical decision-making and moral philosophy in China and the US have been changed over the decade. This study relies on the results presented by Whitcomb, Erdener, and Li (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) to understand ethical decision-making and the associated moral philosophy prevalent in China and the US in the mid-1990s. Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) carried out a survey using five ethical vignettes developed by Fritzsche and Becker (Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984) to explore Chinese and American decision-making for various ethical dilemmas and the rationales behind the decisions. We conducted a survey using the same series of ethical dilemma scenarios to understand Chinese and American managers’ ethical decision-making and the associated moral philosophy in the mid-2000s. Our data, in conjunction with the results of Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998), allow us to examine whether and how managerial ethics changed in the two countries over the decade.

This study contributes to our understanding of whether and how cross-cultural ethical decision-making evolves over time in accordance with convergent, divergent, or crossvergent viewpoints. It is an interaction of individual values with the outside world that fundamentally reshapes a personal moral worldview. As the nature of business has become increasingly globalized, and cultures across countries continue to adapt to new circumstances, there has been a call to look at this interaction longitudinally over time (Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Pounder, Lo, Wong, Egri and Stauffer2006; Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Ralston and Crittenden2012). By responding to this call, this study not only provides critical insights into cross-cultural evolution in business ethics but also contributes to a better understanding of how convergence, divergence, and crossvergence perspectives actually work in dealing with ethical decision-making in a world of increasing cross-cultural and multicultural interactions.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Business Ethics and Values in China and the US

The comparison between China and the US has received significant attention in recent decades in many comparative studies as the two countries provide a true contrast, both culturally and environmentally, characterizing the most distinct cross-cultural differences between the East and the West. In parallel with polar opposite characteristics in sociocultural, political, and economic environments (DiTomaso & Bian, Reference DiTomaso and Bian2018; Nisbett, Reference Nisbett2003; Ralston, Gustafson, Cheung, & Terpstra, Reference Ralston, Gustafson, Cheung and Terpstra1993), many scholars have reported significant differences in various aspects of business ethics and values in the two countries (Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Gustafson, Cheung and Terpstra1993; Shafer, Fukukawa, & Lee, Reference Shafer, Fukukawa and Lee2007). For example, the moral philosophy of the US is strongly influenced by European heritage and Judeo-Christian traditions that, in line with Aquinas's natural law, highlight absolute and retributive justice, resulting in certain fundamental principles of right and wrong (Fritzsche et al., Reference Fritzsche, Huo, Sugai, Tsai, Kim and Becker1995; Silk, Reference Silk1984). In contrast, the moral philosophy of China is rooted in Confucian philosophy that stresses societal order and stability, human relationships, and in-group membership (Bockover, Reference Bockover2010), as well as in Daoism that promotes balance and harmony between humans and nature (Wang & Juslin, Reference Wang and Juslin2009). A meta-analysis by Forsyth, O'Boyle, and McDaniel (Reference Forsyth, O'Boyle and McDaniel2008) on national ethical positions revealed that both China and the US are associated with relatively low idealism (i.e., concern for benign outcomes), indicating that the Chinese and Americans tend to pragmatically admit the unavoidable occurrence of undesirable consequences. However, the Chinese seem to be more relativistic as they base moral judgments on situational events and evaluate actions taken against specific circumstances rather than moral absolutes, whereas Americans are less relativistic as they rely more on cognitive faith in moral principles and universal moral rules for ethical judgments.

Prior research shows that the Chinese and Americans exhibit different ethical attitudes and moral philosophies largely influenced by different cultural and institutional environments. However, such cross-cultural differences between the two countries may not remain intact but change because cultural and institutional environments in both societies evolve over time (Svensson & Wood, Reference Svensson and Wood2003). In particular, there have been substantial environmental changes in China and the US over the past decades, which, in turn, have affected their value system differently. Scholars revealed that the value system of China became more different from that of the US in the 1990s (Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Pounder, Lo, Wong, Egri and Stauffer2006), partly because the change in intergenerational values has been relatively modest in the US, compared to China that experienced more radical sociopolitical and economic changes since the 1950s (Egri & Ralston, Reference Egri and Ralston2004; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997).

Managerial Ethical Decision-Making and Moral Philosophy

Individuals’ personal moral philosophy is an influential factor in the ethical decision-making process (Fritzsche & Becker, Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984). Individuals base their ethical judgments and behaviors on personal moral philosophy that they have developed over a lifetime of experience by confronting and resolving ethical issues (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1992; Weber & Gillespie, Reference Weber and Gillespie1998). Understanding an individual's moral development and moral philosophy is therefore critical to predicting ethical decision-making and behaviors in a business context (May & Pauli, Reference May and Pauli2002; Trevino, Reference Trevino1986).

Fritzsche and Becker (Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984) made an initial attempt to study the link between moral philosophy and managerial ethical behaviors by constructing a series of vignettes that independently deal with five different ethical problems: (i) coercion and control problem that occurs when external forces compel managers to make a specific decision by using threats, extortion, or other sources of power; (ii) conflict of interest problem that arises when managers have multiple, but not mutually compatible, interests that, if mutually pursued, may cause harm to individuals or the company (Beauchamp & Bowie Reference Beauchamp and Bowie1979); (iii) physical environment problem that exists as a particular case of conflict of interest where one affected party is the environment; (iv) paternalism problem that relates to the balance between respect for individual autonomy and commitment to the public welfare; and (v) personal integrity problem that occurs when the decision raises questions of conscience.

Fritzsche and Becker (Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984) suggested three moral theories to explain the managerial decision for each ethical problem. First, rights theories stress individual indisputable entitlements. They focus on the rights and basic legal claims of all individuals such as free consent, freedom of conscience, free speech, privacy, and due process. Second, justice theories concern the distributional effects of actions, behaviors, or policies. They highlight decisions based on fairness, equity, and impartiality, with a particular emphasis on the validity of differential merit-based treatment for individuals according to their contribution to the attainment of organizational goals (Rawls, Reference Rawls1971). Finally, utilitarian theories propose that individuals evaluate behavior in terms of its social consequences. There are two different types of utilitarianism. Rule utilitarianism purports that the individual's actions are judged as ethical or unethical depending on whether they follow certain rules prescribed for a particular action. On the other hand, act utilitarianism asserts that the individual bases decisions solely on their outcomes, and hence, people select the act that provides the greatest social good (Barry, Reference Barry1979).

A number of studies have adopted the vignettes developed by Fritzsche and Becker (Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984) to examine the relationship between moral philosophy and managerial ethical decisions across different national contexts because the five ethical problems and the associated three moral theories are fairly universal, not limited to a certain cultural context (Fok, Payne, & Corey, Reference Fok, Payne and Corey2016; Fritzsche et al., Reference Fritzsche, Huo, Sugai, Tsai, Kim and Becker1995; Paik, Lee, & Pak, Reference Paik, Lee and Pak2019).

Business Ethics in China and the US in the mid-1990s

Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) sought to understand Chinese and American ethical decision-making and the underlying moral philosophy by using Fritzsche and Becker's (Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984) vignettes. Their findings were based on data collected in 1993–1994, which reflect Chinese and American business ethics prevalent in the mid-1990s. This comparative research reported that the ethical decision-making of Chinese and American respondents was not statistically different for three ethical problems (i.e., conflict of interest, physical environment, and personal integrity), whereas their decisions for the other two ethical issues (i.e., control and coercion, and paternalism) were significantly different. Despite the similarity shown in their ethical decision-making, Chinese and American respondents based their decisions on different moral philosophies for all five ethical problems. These results indicate that differences in Chinese and American values tend to be reflected primarily in the rationales behind ethical decisions rather than in the decisions themselves.

Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) highlighted the role of cultural values and institutional environments in ethical decision-making. They argued that the process of institutional transformation in China has left cultural values in a state of flux and that the Chinese value system has been continuously reshaped. The gradual shift from central planning to a market system has affected Chinese values and the way in which economic decisions are legitimized. Compared to American counterparts, Chinese respondents are at least equally (sometimes more) motivated by economic benefit, more willing to accept business practices based on interpersonal relationships, and more likely to use informal means (in some cases, illegitimate from the American point of view) to achieve their profit objective.

HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Three Perspectives on Values Evolution

The main objective of this study is to explore whether and how cross-cultural differences in managerial ethical decision-making and the associated moral philosophy have evolved in China and the US over the decade since the mid-1990s. It is noteworthy that, as Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) demonstrated, similar ethical decisions may come with different justifications. In other words, managerial ethical decision-making and the moral philosophy underlying those decisions may neither correspond with each other nor evolve in the same direction in diverse cultural contexts.

We build on three alternative perspectives of values evolution, namely, global convergence, societal divergence, and multicultural crossvergence (Dunphy, Reference Dunphy1987; Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Holt, Terpstra and Kai-Cheng1997) that describe how sociocultural, economic, and political influences affect individuals’ ethical judgments (Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Ralston and Crittenden2012). First, convergence advocates argue that industrialization and technological development will lead to the global convergence of values across societies. Cross-national differences will decrease over time because commonly held technology will shape both educational demands and business structures in a similar way, which, in turn, generate shared values (Dunphy, Reference Dunphy1987; Webber, Reference Webber1969). While industrialization and technological influence are considered the primary driving forces for values convergence, the political system (i.e., democracies) and economic development that are largely interrelated to technological sophistication also have substantial influence on the convergence of value systems (Ralston, Reference Ralston2008). Therefore, the convergence perspective would predict that any differences in ethical decision-making and the associated moral philosophy in China and the US would disappear or significantly decrease over time, such that they would become more similar in the two countries over a decade from the mid-1990s.

On the contrary, proponents of the divergence perspective believe that sociocultural influence will make individuals retain the specific value system of the societal culture over generations, and hence, differences in cross-cultural values will remain intact over time or change very slowly (Webber, Reference Webber1969). The value system of a society is the product of sociocultural influences that are deeply embedded in its cultural roots. Values and beliefs acquired during childhood socialization persist throughout one's lifetime, regardless of technological, economic, and political changes (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997; Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Pounder, Lo, Wong, Egri and Stauffer2006). Thus, the divergence perspective would predict that individuals will retain a particular value system of the national culture even if a country adopts new business ideology and that any differences in ethical decision-making and the associated moral philosophy in China and the US would remain intact over time, regardless of various changes in the business environment.

Finally, crossvergence is described as the synergistic interaction of convergence and divergence effects within a society that results in a unique value system (Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Pounder, Lo, Wong, Egri and Stauffer2006). Crossvergence theory contends that business ideology influences (such as economic, political, and technological influences) that are closely related to business activity in a society take a relatively short time period for change (i.e., years or decades) while sociocultural influences that are closely associated with a society's core social values require a much longer time horizon for change (i.e., generations or centuries). Therefore, the dynamic interaction of the two macro-level (i.e., business ideology and sociocultural) influences that require different times to change an individual's values will lead to the development of a new value system among individuals in a society over a period of time. Crossvergence perspective would predict ethical decision-making and the associated moral philosophy in China and the US may evolve in various ways depending on specific ethical problems over time.

Ethical Decision-Making

Global institutional pressures aiming to improve business ethics and social responsibilities have substantially increased over the past two decades (e.g., United Nations Global Compact since 2000). In contrast to the dominant market logic skewed on profit maximization, such global institutional pressures have multiple goals to ensure that a company's business model incorporates a wide range of social and sustainability issues related to different stakeholders. These pressures have increasingly established an array of global ethical standards that companies need to meet to sustain their legitimacy and to be accepted as social actors (Waddock, Reference Waddock2008). These changes mainly concern business ideology influences that require a considerably shorter time for change, compared to sociocultural influences (Ralston, Reference Ralston2008). Therefore, in order to effectively meet global institutional pressures for enhanced business ethics and social responsibilities, both Chinese and American managers are likely to make more ethical decisions in the mid-2000s than in the mid-1990s. However, this does not necessarily mean that cross-cultural differences in the ethical decision-making between the two countries revealed in the mid-1990s will diminish or disappear in the mid-2000s (i.e., convergence).

Instead, we predict that ethical decision-making in China and the US would evolve distinctively depending on specific ethical problems over the decade (i.e., crossvergence). The five ethical problems are associated with different societal values, and thus, they might not be considered as ethics-related issues to the same degree in the two countries. Put differently, some ethical issues can be regarded as serious and socially, even legally, constrained problems in the US, while they are not so much in China (and vice versa). For instance, the pace of regulatory or legal institutional developments concerning foreign corruption and physical environmental protection varies between China and the US, and therefore, ethical decision-making for coercion and control issues and physical environmental issues may evolve differently in China and the US. By contrast, the global development of ‘hypernorms’ or basic principles fundamental to human life (Donaldson & Dunfee, Reference Donaldson and Dunfee1994, Reference Donaldson and Dunfee1999) may encourage both Chinese and American managers to make similar ethical decisions concerning paternalism and personal integrity issues.

Therefore, the interaction between business ideology influences (i.e., global institutional pressures for enhanced ethical standards) and sociocultural influences (i.e., national culture and institutions) may lead specific values to change in different degrees as well as in different directions, and eventually, create differences in changes between the two countries over a decade. As a result, the reported differences in ethical decision-making in China and the US in the mid-1990s may disappear for some ethical problems but remain intact for others in the mid-2000s. It is also plausible that new differences between the two countries may arise for some ethical problems in the mid-2000s, which reported no differences in the mid-1990s. In sum, we advocate the crossvergence perspective for managerial ethical decision-making in China and the US over a decade, and Hypothesis 1 is formed as follows:

Hypothesis 1: There has been a variation across ethical problems in the differences in ethical decision-making between Chinese and American managers over the period from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s.

Moral Philosophy

National culture significantly influences the development of an individual's moral philosophy and value systems that are used to make ethical judgments (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Kwon, Stoeberl and Baumhart2003; Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1992) because individuals develop personal moral philosophy by confronting various ethical issues in a specific cultural setting (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1992; Weber & Gillespie, Reference Weber and Gillespie1998). Even if a country adopts a new business ideology, and thus, individuals change their ethical decisions and behaviors, it is often more difficult and takes a longer time to change the individual's moral philosophy and value system (Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Holt, Terpstra and Kai-Cheng1997). National culture that shapes the moral philosophy as a group's collective being is sufficiently powerful to make managerial values continue to remain different for people and businesses from other countries despite the adoption of similar economic and business ideologies (Robertson & Crittenden, Reference Robertson and Crittenden2003). In particular, the Chinese with a long history of a socialist economy and strong Confucian philosophy would not shift their value system, at least in a short period of time, irrespective of economic and political changes that have occurred in China over a decade. China has been in an apparent transition to market economy for the past few decades, but the economic ideology still adheres to the collectivistic notions of socialism. In other words, socialistic philosophy that values the protection of the rights of society still applies to the ownership of means of production (Naughton, Reference Naughton2017). Although Confucianism should not be overly stressed when examining a complex, multi-faceted, and rapidly changing business context in China, Confucianism is still considered influential in how businesses are managed, and Confucian values actively inform social values in China (Atherton, Reference Atherton2020). Not only Confucianism, but traditionalism that includes all schools of ancient Chinese thought also plays a critical role in everyday life, intellectuals, and politics of Chinese people (Yan, Reference Yan2018).

Therefore, this study predicts no major changes in cross-cultural differences in moral philosophy between the two countries, as it reflects a society's core social values. That is, the reported differences in Chinese and American moral philosophies underlying ethical decisions in the mid-1990s remain unchanged in the mid-2000s. Thus, the moral philosophy used to make ethical decisions between Chinese and American managers would still be different from each other in the mid-2000s regardless of specific ethical issues involved, as they were in the mid-1990s. In sum, we advocate the divergence view for moral philosophies in China and the US over a decade, and Hypothesis 2 is formed as follows:

Hypothesis 2: There have been continued differences in moral philosophy behind the ethical decisions between Chinese and American managers over the period from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s.

METHODS

Sample

We collected our sample between 2005 and 2007 in China and the US. The American sample was comprised of 200 managers and business professionals from 42 southwestern US companies across various industries, including aerospace/defense, financial services, entertainment, retail, healthcare, telecommunications, snack food, and professional services. The respondents’ mean age was 37.4 years (SD = 8.65). The sample consisted of 110 males (55%) and 90 females (45%). 70% of the sample had attained an undergraduate college degree, while 24% had earned a master's degree or above. The Chinese sample consisted of 204 managers from various sectors, including banking, information technology, security, transportation, food, chemical, aviation, retail, biotechnology, logistics, and publication. The mean age of the Chinese respondents was 33.9 years (SD = 7.82). The sample consisted of 133 males (65%) and 71 females (35%). 77% of the respondents had an undergraduate college degree, and 19% had earned a master's degree or above.

Procedure

The American respondents were recruited from four sources in 2005. First, 40 participants in an executive education program at a private US west coast university were asked to participate in the study, and 33 executives (83%) agreed to participate. Second, 34 mid-level managers from a food manufacturing company were asked to participate as part of a one-day management training program, and 28 managers agreed to participate for a response rate of 82%. Third, 110 fully-employed MBA students at a public US west coast university were invited to participate in the study, and 99 students completed the survey for a response rate of 90%. The final source of respondents consisted of 50 alumni executive education students at a US private west coast university, and 40 executive education alumni agreed to participate for a response rate of 80%. The overall response rate for the study across the four sources was 85%.

The Chinese data were collected in 2007 by distributing the questionnaire to 353 managers who enrolled in an executive education program and an EMBA program at one of the top universities in Beijing. While 219 managers returned their questionnaire, 15 surveys were incomplete and had to be discarded. The final Chinese sample achieved an overall response rate of 58%.

To ensure the reliability and validity of the Chinese data, the Chinese version of the questionnaire was thoroughly cross-checked by three bilingual researchers in China. The English version of the questionnaire was first translated into Chinese by two bilingual researchers, and the Chinese version was reverse-translated into English by two independent bilingual individuals to ensure that both Chinese and English versions of the questionnaire were equivalents. To avoid any ambiguity in the questions and to ensure a clear understanding of all questions by respondents, the Chinese version of the questionnaire was pretested with five MBA students and five managers who were enrolled in a short training program at a top business school in Beijing.

Measures

Following Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998), this study used the same series of vignettes developed by Fritzsche and Becker (Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984) to measure the ethical decision-making and moral philosophy used to make the decisions. Respondents were asked to assume the role of the decision-maker and to provide two responses for each vignette: (i) ethical decision-making and (ii) the rationale to support their decisions. The use of vignettes, compared to the use of simple questions, allows researchers to inject a greater amount of background information into an ethically questionable issue and hence elicit higher quality data from respondents in ethical research (Alexander & Becker, Reference Alexander and Becker1978).

The first vignette represents a coercion and control problem. It illustrates a company manager that has been barred from entering a particular foreign market and is required to pay a country businessman $500,000 to gain access to that market, which has been estimated to have the potential to net $5 million in profit per year. Respondents are asked to indicate the likelihood that they, as a company manager, would pay the price.

The second vignette concerns a conflict of interest problem that describes a new employee who is requested by his new employer to reveal new product information of his former employer. Respondents are asked to indicate the likelihood that they, as a new employee, would provide the new employer with this information.

The third vignette is about a physical environment problem and concerns a decision on whether to use a new milling process during the night shift that will provide the company with an edge on competitors but will also exceed legal limits on air pollution. Respondents are asked to indicate the likelihood that they would approve the use of the new process.

The fourth vignette deals with a paternalism problem and describes an editor who wants to publish an authoritative account of the history of the development of the atomic bomb, but who failed to persuade the author to omit the final chapter that, from the editor's perspective, should not be made readily available to the mass market as it contains a detailed description of how a bomb is made. Respondents are asked to indicate the likelihood that they, as an editor, would publish the book.

The fifth vignette concerns a personal integrity problem. It illustrates a product development manager working in an auto parts contracting company who needs to decide whether to whistle-blow on his employer that is ignoring a supplied part defect in an attempt to keep an important contract with an auto manufacturer for the company's survival. Respondents are asked to indicate the likelihood that they, as a product development manager, would notify the auto manufacturer of the defect.

Respondents were asked to indicate their decisions (likelihood) for each vignette on a scale of 0 (definitely would not) to 10 (definitely would). For vignettes 1–4, a higher score indicates a behavior of questionable morality and a preference for economic values over ethical values. On the contrary, a higher score indicates an ethical behavior (i.e., whistleblowing) and a preference for ethical values for vignette 5.

After providing a decision rating for each vignette, respondents were asked to indicate the rationale behind their decisions. The rationales were presented in a multiple-choice format including an open-ended option.[Footnote 1] While the rationale options represent one of four ethical theories (rule utilitarianism, act utilitarianism, rights theory, and justice theory), we coded the participant's responses into three categories, focusing on two utilitarian theories (i.e., rule utilitarianism, act utilitarianism, and others) for two reasons. First, Fritzsche and Becker (Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984) and most subsequent studies using their vignettes have concluded that the rationale provided by the respondents, irrespective of national culture and time, was predominantly of a utilitarian nature (either rule or act) rather than rights or justice theories (Fok et al., Reference Fok, Payne and Corey2016; Premeaux, Reference Premeaux2004). Second, the rationale alternatives in all five vignettes included options that were rule utilitarian or act utilitarian in nature (Fritzsche & Becker, Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984). There were also very few qualitative responses from the participants who provided their rationale using the open-ended option. We carefully coded these responses into the above three categories.[Footnote 2]

RESULTS

Tables 1–5 present the results of the ethical decision-making and moral philosophy underlying the decisions of Chinese and American managers in the mid-2000s in comparison to those in the mid-1990s presented by Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998). We conducted a t-test to assess the difference in the mean score of ethical decision-making between Chinese and American managers. Then, a χ 2 test was performed to see if there is a significant difference in the frequency distribution of the moral philosophy between Chinese and American respondents.

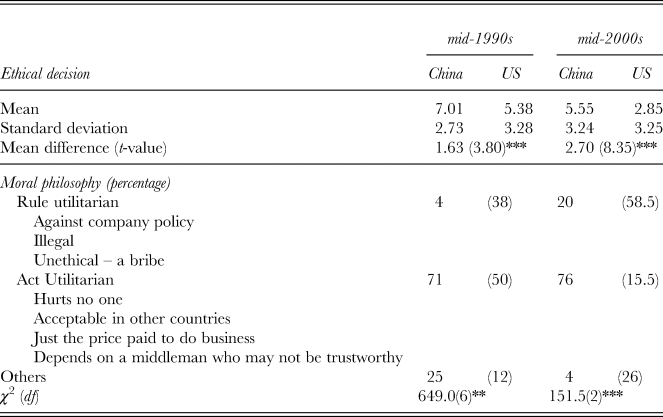

Table 1. Comparison of ethical decision-making and moral philosophy in China and the US for coercion and control issue (vignette 1)

Notes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

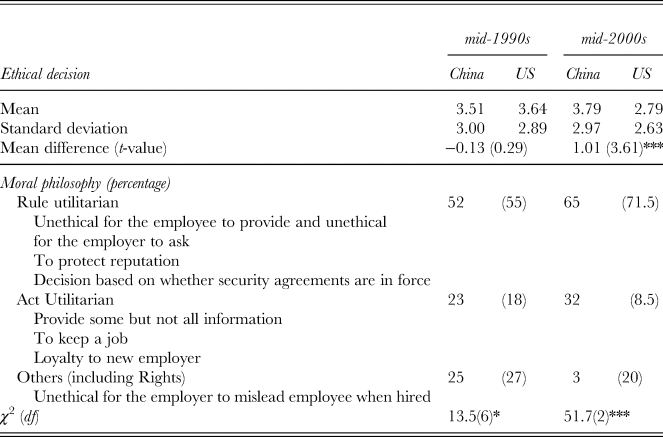

Table 2. Comparison of ethical decision-making and moral philosophy in China and the US for conflict of interest issue (vignette 2)

Notes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

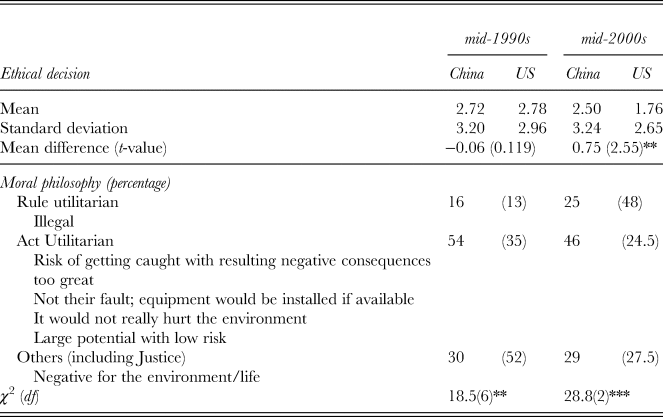

Table 3. Comparison of ethical decision-making and moral philosophy in China and the US for physical environmental issue (vignette 3)

Notes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

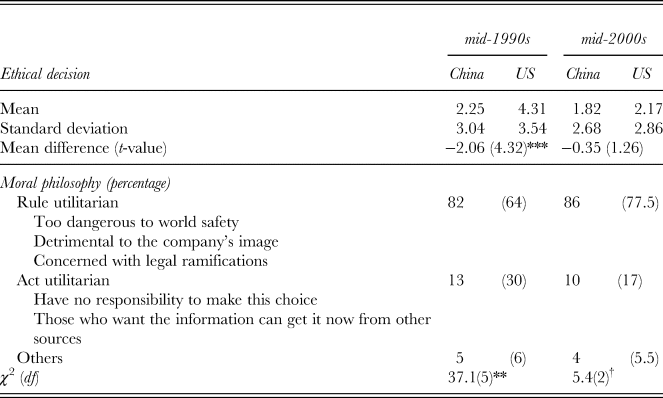

Table 4. Comparison of ethical decision-making and moral philosophy in China and the US for paternalism issue (vignette 4)

Notes: †p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

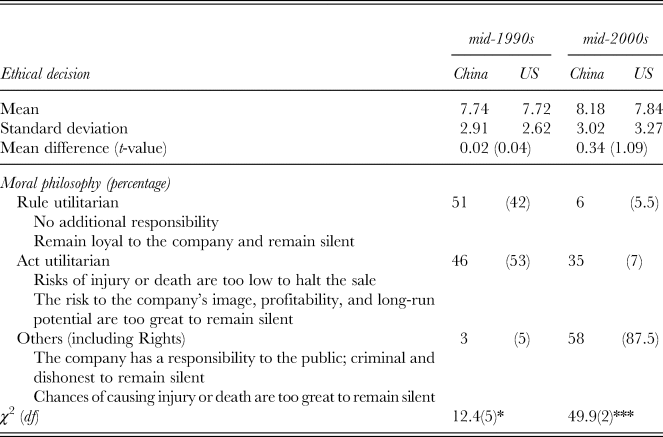

Table 5. Comparison of ethical decision-making and moral philosophy in China and the US for personal integrity issue (vignette 5)

Notes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 1 concerns the coercion and control problem. Our results revealed that the Chinese and the US respondents made significantly different ethical decisions (p < 0.001) and showed different distributions in moral philosophy behind their decisions in the mid-2000s (p < 0.001) as they did in the mid-1990s. Cramer's V that shows the effect size for the χ 2 test was 0.612, indicating a large effect size and a strong association between the nationality and the moral philosophy underlying managerial ethical decisions for the coercion and control problem (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988; Gravetter & Wallnau, Reference Gravetter and Wallnau2007).[Footnote 3] Inconsistent with the findings of Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998), our Chinese respondents are more likely to make a payment to a local businessman to get their products into the foreign market than the US respondents. In terms of moral philosophy behind their decisions, Chinese respondents still overwhelmingly based their decisions on an act utilitarian philosophy, while US respondents have come to rely much more on rule utilitarianism than act utilitarianism.

Table 2 shows the results for the conflict of interest problem. Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) found no significant difference in the ethical decision-making between Chinese and American managers in the mid-1990s. However, our sample in the mid-2000s showed a significant difference in their ethical decision-making (p < 0.001). Regarding the moral philosophy behind the ethical decisions, Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) reported that Chinese and American managers rely on different moral philosophies to make their decisions for the conflict of interest problem. Our samples also demonstrated that the distribution of underlying moral philosophy was significantly different between Chinese and American respondents (p < 0.001). Cramer's V was 0.358, indicating a large effect size.

Table 3 concerns the physical environment problem. The results showed a similar pattern with the conflict of interest problem. Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) reported no significant difference between Chinese and American respondents for their ethical decisions in the mid-1990s. However, our sample detected Chinese and American managers made different ethical decisions for the physical environment dilemma in the mid-2000s (p < 0.01). As Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) found a significant difference in the underlying moral philosophy for the decision concerning the physical environment problem, we also found the difference in the moral philosophy distribution between the Chinese and American respondents in the mid-2000s (p < 0.001). Cramer's V showed 0.267, indicating a medium effect size.

Table 4 shows the results of the paternalism problem. Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) showed that there was a significant difference in ethical decision-making between Chinese and US samples in the mid-1990s. However, our sample showed such difference disappeared in the mid-2000s. Both Chinese and American managers continued to base their decisions for the paternalism problem on rule utilitarianism over the decade, but the χ 2 test results indicated that the frequency distribution of the moral philosophy used by Chinese and American respondents was significantly different from each other in both Whitcomb et al.'s (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) sample (p < 0.01) and our sample (p < 0.1). Cramer's V for our sample showed 0.116, indicating a small effect size. This result suggests that there is a weak relation between the nationality and the moral philosophy used to make ethical decisions concerning the paternalism problem.

Finally, Table 5 reports the results of the personal integrity problem. Unlike the other four ethical problems, a higher mean score indicates a preference for ethics over economic value for the personal integrity issue. Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) found no significant difference in the ethical decision-making between Chinese and American respondents in the mid-1990s, and we found no significant change has been made over the decade. In other words, the ethical decisions of Chinese and US managers were not significantly different from each other in the mid-2000s. Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) reported that the distribution of ethical philosophy used by Chinese and American managers was different in the mid-1990s. Our sample revealed that such difference remained and became even stronger in the mid-2000s (p < 0.001). Cramer's V showed 0.352, indicating a large effect size.

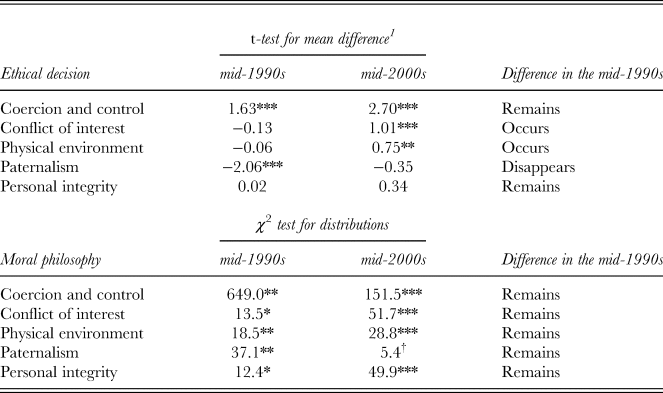

Table 6 presents a summary of the comparison of Chinese and US samples over the decade for hypotheses testing. The results show that the differences in ethical decision-making between Chinese and American respondents in the mid-1990s have evolved independently in various plausible ways over the decade, supporting Hypothesis 1 (crossvergence perspective). Specifically, Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) reported that there were differences in Chinese and American decision choices for the coercion and control problem (vignette 1) and the paternalism problem (vignette 4) in the mid-1990s. However, our sample revealed that the difference in the coercion and control problem remained in the mid-2000s, while the difference in the paternalism issue disappeared over the decade. On the other hand, Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) found no differences in ethical decisions for the other three issues in the mid-1990s. However, we found that the differences occurred for two ethical issues, that is, conflict of interest issue (vignette 2) and physical environment problem (vignette 3), in the mid-2000s. Only the personal integrity issue has consistently discovered no difference between the Chinese and US respondents from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s.

Table 6. Summary of the evolution in ethical decision-making and moral philosophy in China and the US from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s

Notes: 1Mean difference shows the Chinese mean score subtracted by the US mean score.

†p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Inconsistent with Whitcomb et al.'s (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) findings, our results for the rationale distributions behind ethical decision-making revealed that the significant differences in moral philosophy between Chinese and American respondents remained over the decade across all five ethical problems, lending support to Hypothesis 2 (divergence perspective). Although our results discovered some changes in the magnitude of the differences over the decade, we found that the moral philosophies employed by Chinese and American respondents were significantly dissimilar in the mid-2000s in all five ethical problems.

DISCUSSION

Ethical Decision-Making

Our comparison of business ethics in China and the US implies a crossvergence of ethical decision-making from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s. In particular, the crossvergence effect seemed more evident in China that has experienced dramatic economic and political changes over the past decades, compared to the US which has gone through relatively subtle changes during the same period (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997; Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Pounder, Lo, Wong, Egri and Stauffer2006).

Our results revealed that Chinese managers did not demonstrate much difference in their decisions for the conflict of interest issue and physical environmental issues between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, while American managers displayed significant changes, making more ethical decisions for both issues in the mid-2000s than in the mid-1990s. For the conflict of interest issue, the result may reflect the joint influence of traditional Confucian values and new market ethics. Confucian values strongly emphasize loyalty. Confucian ethics demands the reciprocal obligations of a superior to take care of his subordinate in return for loyalty from the subordinate. Confucian ethics would not anticipate that a new employer would ask a new employee to divulge a new product secret of the previous employer, as the new employer is likely to be considered deceptive and undeserving loyalty. Market ethics, on the other hand, would emphasize personal job security, market rules, or personal reputation over loyalty to the former employer. Chinese managers, being confronted by these seemingly conflicting values, tended to seek compromises, either through legal means such as security agreements or the provision of some but not all information in the mid-1990s (Whitcomb et al., Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998). Our results suggest that such a tendency seems to remain and even becomes stronger in the mid-2000s.

For the physical environment problem, we found the same pattern as the conflict of interest issue. That is, there was no significant difference in their ethical decision-making in the mid-1990s but a significant difference occurred between Chinese and American managers in the mid-2000s. However, our sample suggests that both Chinese and American managers tend to make a more ethical decision for the physical environment problem in the mid-2000s, as indicated by the lower mean score (i.e., preference for moral value). This change probably has to do with global institutional pressures for environmental protection and sustainability. In the US, as early as the 1970s, the federal government established a range of environmental protection legislation (e.g., National Environmental Policy Act in 1970, Clean Air Act in 1970, and Water Pollution Control Act in 1972), which has been frequently amended to address newer environmental problems such as acid rain and ozone depletion (Caldwell, Reference Caldwell1998; Waxman, Reference Waxman1991). In China, such environmental regulations were established in the 1980s, but during its rapid industrialization and economic development, China adopted a ‘grow first, clean up later’ environmental strategy, overlooking environmental degradation to sustain high-speed growth and technological catch-up with the West (Liu, Reference Liu2012; Rock & Angel, Reference Rock and Angel2007). As a result, nearly half of the American respondents (48%) perceived the use of a new process that exceeds legal limits on pollution as illegal in the mid-2000s while only 13% perceived it as illegal in the mid-1990s. In stark contrast, 16% of Chinese respondents perceived such decisions as illegal in the mid-1990s and only 25% perceived it as illegal even after a decade in the mid-2000s. This result confirms the vital role that governmental and inter-governmental regulatory authorities can play in managerial ethical decision-making.

The results for the coercion and control issue also reflect institutional differences between the two countries, especially the regulative pillar. For this issue, both Chinese and American managers showed a much lesser likelihood of paying bribes to smooth out problems in foreign countries in the mid-2000s. We believe this change also has to do with global convergence effects of political influence that encompasses the legal system and the integrity (e.g., corruption level) of a society (Ralston, Reference Ralston2008). A number of studies have reported a significantly higher propensity of American managers to reject coercive action designed to extort a bribe, due to the enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in the US as early as 1977 (Becker & Fritzsche, Reference Becker and Fritzsche1987; Fritzsche et al., Reference Fritzsche, Huo, Sugai, Tsai, Kim and Becker1995; Whitcomb et al., Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998). However, it was only in the late 1990s when such regulations (i.e., prohibiting bribery abroad) were introduced and implemented around the world (e.g., Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions) (Cuervo-Cazurra, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra2008). Although China is yet to join the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, such global institutional pressure would have made Chinese managers comply with international norms and led them to make more ethical decisions in the mid-2000s than in the mid-1990s. However, our results indicated that Chinese managers are still more likely to make grease payments in foreign countries, compared to American managers. This result corroborates the previous findings that, while ethics matters for management decision-making, it is easier to be ethical when the law is behind one's decision (Becker & Fritzsche, Reference Becker and Fritzsche1987).

For both paternalism and personal integrity issues, we found no significant differences in ethical decision-making between Chinese and American managers in the mid-2000s. While Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) reported a difference in the paternalism issue in the mid-1990s, this difference disappeared in the mid-2000s as American managers moved toward more ethical decision-making. Likewise, no significant difference was detected for the personal integrity issue between the two groups in the mid-2000s as it was in the mid-1990s. These findings may, in fact, be a result of global convergence on hypernorms that represent the basic principles fundamental to human existence (e.g., human life, core human rights, and human dignity) and hence apply to all people worldwide (Donaldson & Dunfee, Reference Donaldson and Dunfee1994, Reference Donaldson and Dunfee1999). By publishing the book (vignette 4) and by not blowing the whistle (vignette 5), both Chinese and American respondents may perceive that they would violate a hypernorm, the basic human rights of physical security, regarded as the universal moral value (Fritzsche et al., Reference Fritzsche, Huo, Sugai, Tsai, Kim and Becker1995).

Moral Philosophy

Our results also revealed that American managers have increasingly utilized rule utilitarian philosophy rather than act utilitarian philosophy when making ethical decisions, while Chinese managers tend to rely more on act utilitarianism. In particular, this tendency is evident in the coercion and control, conflict of interest, and physical environment problems where significant differences in ethical decision-making between Chinese and American managers were either unchanged or newly discovered. These results confirm the conventional wisdom that managers who base their decisions on act utilitarian philosophy are more likely to prefer economic value to moral value (Fritzsche & Becker, Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984; Premeaux, Reference Premeaux2004; Whitcomb et al., Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998). They also manifest the cross-cultural variation in the ethics position shared for a long time by people in a particular society. Forsyth et al. (Reference Forsyth, O'Boyle and McDaniel2008) concluded in their meta-analysis that Eastern and Western countries tend to have different moral philosophies. Americans have been recognized as exceptionists who endorse the value of moral principle (low relativism) while pragmatically balancing the positive consequences of an action against the negative consequences of an action (low idealism). Therefore, an American's outlook corresponds to a moral philosophy based on rule utilitarianism. On the other hand, the Chinese tend to be subjectivists who are also open to exceptions to moral rules (low idealism), but believe that individual values should guide their ethical decisions (i.e., subjective judgments) rather than moral absolutes or universal moral principle (high relativism) (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1980; Forsyth et al., Reference Forsyth, O'Boyle and McDaniel2008). In the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, an economic growth imperative has dominated the social value and institutional infrastructure in China. Economic achievements are assigned the highest priority, and hence, when conflicts occur, non-economic goals give way to economic ones. The outcome-based utilitarian logic of the marketplace has become prevalent and penetrated the institutional realm in China (Luo, Reference Luo2008).

At this point, it is not only interesting but also important to look into the generational value orientation of our respondents to understand the moral philosophy that they use. The generational value orientation plays a pivotal role in understanding the evolutionary process of culture change (Inglehart & Baker, Reference Inglehart and Baker2000; Weber, Reference Weber2019). National culture is not homogeneous across generations in a society, but generation cohorts reflect and represent the values emphasized during a particular historical period and their formative years. A generation's value orientation becomes more pervasive in a national culture because it becomes the majority in societal positions of power and influence (Egri & Ralston, Reference Egri and Ralston2004; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997). Cross-cultural research on generational value change has typically used common age groups to assess the value orientation of generation cohorts. A simple calculation between the average age of our sample and the time when the survey was conducted suggests that our Chinese respondents consist of the ‘Social and Economic Reform’ generation (hereafter the Reform generation) (born 1971–1975), whereas our American respondents belong to ‘Generation X’ (born 1965–1979) (Egri & Ralston, Reference Egri and Ralston2004; Strauss & Howe, Reference Strauss and Howe1991). In the same manner, we could find that, in the Whitcomb et al. (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) study, Chinese respondents also consisted of the Reform generation, while the American respondents were Generation Xers. Therefore, this study compares the same birth cohort in China and the US between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s. This allows us to minimize potential confounding effects caused by intergenerational values differences (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997) and focus on examining the longitudinal changes in value systems and business ethics in two countries.

In their comparison between the values orientation of the Chinese Reform generation and American Generation Xers, Egri and Ralston (Reference Egri and Ralston2004) concluded that they are similar in terms of being highly open to change and less conservative than their prior generations. However, the Reform generation is significantly less self-enhancing than the American Generation Xers, meaning that they have less concern about achieving personal success through demonstrated competence and attaining social status and control over others. The Reform generation is also less self-transcendent compared to Generation Xers, meaning that they have less concern about protecting and enhancing the well-being of their close contacts as well as the welfare of all people and nature (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1994). These characteristics of the Chinese Reform generation are congruent with the tendency shown in our study that Chinese managers tend to base their decisions on an act utilitarian philosophy associated with market-oriented reforms. This phenomenon is particularly well illustrated in coercion and control, conflict of interest, and physical environmental issues.

Theoretical Implications

First, to the best of our knowledge, this study represents a pioneering research effort that empirically tests the effects of convergence, divergence, and crossvergence on ethical decision-making and its moral justification in a cross-cultural and cross-temporal setting. Prior literature has mainly focused on the conditions of divergence in international business ethics. Much of the literature has argued that business activities and management principles perceived as ethical or unethical vary across cultures because national culture strongly influences an individual's moral philosophies and value systems underlying ethical judgments (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Kwon, Stoeberl and Baumhart2003; Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1992; Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Holt, Terpstra and Kai-Cheng1997). On the contrary, some scholars have stressed the view of convergence. They argued that basic morality remains the same across national cultures in some situations, and there is more commonality in ethical values and principles across societies than commonly anticipated (Bailey & Spicer, Reference Bailey and Spicer2007; DeGeorge, Reference DeGeorge1993). Researchers also highlighted that cultures evolve over time, and so do ethical values and principles in a society. Unique business ethics in a specific cultural setting at a specific time may change over time, particularly with increasing cross-cultural interactions (Svensson & Wood, Reference Svensson and Wood2003). Nevertheless, very little research has examined the evolution of cross-cultural differences in international business ethics. Our study adds to the literature by revealing that the differences in the ethical decision-making of Chinese and American managers evolved into varied directions in different degrees over the decade, whereas those in the ethical philosophy underlying their decisions strongly displayed the influence of divergence. These findings demonstrate that, as culture and predominant values in a society evolve in relation to the degree of globalization engagement (Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Pounder, Lo, Wong, Egri and Stauffer2006), cross-cultural differences in ethical decision-making and moral philosophies of business managers evolve distinctively over time. These findings extend our current understanding of the evolution in international business ethics in a world of increased cross-cultural and multicultural interactions.

Second, our findings reaffirm the crossvergence perspective by showing that ethical decision-making and the associated moral philosophies require different time spans to have an impact on an individual's values change. New norms (i.e., managers’ inclination to make an ethical decision regardless of their cultural backgrounds) may be rather easily adopted across borders, whereas traditional values in their respective societies rarely change over a short period of time. Put differently, although managers may feel it is not too difficult to emulate the new norms (i.e., ethical behaviors promoted by international organizations such as the United Nations and the OECD), their ethical philosophies embedded in sociocultural values appear to be much more difficult to manipulate.

Finally, this study demonstrates that the crossvergence perspective provides a useful lens through which we can examine the evolution of international business ethics. Although a few studies have built on the convergence and divergence debate (Bailey & Spicer, Reference Bailey and Spicer2007; Jamali & Neville, Reference Jamali and Neville2011), little research has addressed the crossvergence perspective on international business and managerial ethics. Our findings suggest that globalization and the associated global institutional pressures may be the primary influences that change managerial ethical decision-making, but that there is also a substantial interaction with sociocultural values such as moral philosophies evolving over time (Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Pounder, Lo, Wong, Egri and Stauffer2006).

Managerial Implications

Our findings provide important implications for policymakers and managers, particularly those in China. First, this study demonstrates the crucial role of institutions in managerial ethical decision-making. The institutional development in the form of a legal framework, particularly concerning overseas bribery and physical environmental issues, would lead Chinese managers to make more ethical decisions. For instance, China amended its Criminal Law in 2011 to cover overseas bribery issues, and such an amendment is regarded as the first step to join the OECD convention (Fry, Reference Fry2013). In 2014, the Chinese government revised its environmental protection law for the first time since 1989, stating that this revision would have an important effect on the future of China's environmental protection efforts. Over the last decade, the Chinese government made substantial efforts to examine the practice of international anti-corruption cooperation and integrate them domestically into the national legal system (Haowen & Gui, Reference Haowen and Gui2020). While these amendments are partly driven by global institutional pressures, we believe such improvement in the regulative pillar would influence Chinese managers to make more ethical decisions related to coercion and control problems such as overseas bribery, and environmental protection (Yin, Reference Yin2017).

Second, although Chinese and American managers were found to make similar ethical decisions in some business situations (e.g., paternalism and personal integrity issues), they seem to have different rationales to justify their decisions. This result suggests that even if a common international code of ethics for MNCs could be derived, the way in which they persuade their foreign stakeholders including subsidiary employees needs to be adjusted for the cultural values and economic and political institutions of the host country (Whitcomb et al., Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998). Moreover, it would be worthwhile to consider the varying strengths of the relationship between the nationality and the moral philosophy behind ethical decisions across different ethical issues. As indicated by different effect sizes for our χ 2 tests, the manager's nationality tends to have strong relationships with moral philosophies for the coercion and control, conflict of interest, and personal integrity issues, while it has relatively weak relationships for the paternalism and physical environmental issues. Thus, when MNCs devise a common code of ethics for their Chinese and American employees, they may need to consider cultural differences more carefully for the coercion and control, conflict of interest, and personal integrity problems.

Finally, this study showed that managerial ethical decision-making in a society is not invariable, but it may evolve over time and that the evolution of business ethics varies considerably across different ethical issues and cultural settings. While this could be largely influenced by a generation's values orientation (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997), it is equally important that both policymakers and business leaders play their own roles. The former should develop and institutionalize the appropriate regulations to support the process of adopting new norms in a timely manner. The latter should adjust their codes of ethics and guide their organizations in line with societal norms evolution as well as cultural and institutional changes in a society. This will enhance their ability to recognize potential ethical consequences and, hence, make appropriate decisions that engender stakeholder trust.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

First, this research sheds light on business ethics evolution between China and the US, focusing on the period between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s. Our findings provide clear evidence of a need for further cross-cultural, longitudinal investigation of the role played by multicultural interactions along with globalization. Specifically, the differences in managerial ethics between China and the US reported in this study could have changed over the past decade. Future research will contribute to our knowledge of international business ethics evolution by extending the period of the present study to examine how the ethical decision-making and moral philosophies of Chinese and American managers have recently evolved. Moreover, future research should extend our findings by investigating cross-cultural and cross-temporal business ethics in different country contexts.

Second, we collected our data on Chinese and American managers’ ethical decision-making and the moral philosophy in the mid-2000s and compared them with Whitcomb et al.'s (Reference Whitcomb, Erdener and Li1998) findings of Chinese and American managers’ ethical decision-making and the moral philosophy in the mid-1990s. To ensure the validity and the robustness of the analysis, we collected our data using the same series of ethical dilemma scenarios developed by Fritzsche and Becker (Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984). Our samples are also drawn from the same birth cohort in the two countries. However, we acknowledge that the samples from the two studies may be dissimilar, particularly in their work experience that may provide a different context to thinking about what one might do when confronted with ethical dilemmas at the workplace. This point needs to be taken into account when interpreting our results.

Third, we acknowledge the common limitation associated with the research using Fritzsche and Becker (Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984) vignettes. While there are several benefits for using vignettes rather than simple questions in business ethics research (Alexander & Becker, Reference Alexander and Becker1978), we recognize some methodological concerns including the social desirability phenomenon in measuring ethical intentions rather than actual behaviors (Fritzsche & Becker, Reference Fritzsche and Becker1984; Fritzsche et al., Reference Fritzsche, Huo, Sugai, Tsai, Kim and Becker1995).

Finally, intergenerational differences in values orientations play an important role in cross-cultural studies (Egri & Ralston, Reference Egri and Ralston2004; Inkson, Arthur, Pringle, & Barry, Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997). However, there has been little cross-cultural research that takes the generational subculture into account. This study has compared specific generation cohorts in China (Reform generation) and the US (Generation X) in the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, whose values orientations tend to become more pervasive in national culture in the near future as they become the majority in societal positions of power and influence (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997). Therefore, our sample may not represent Chinese and American managers of different generations. In addition, both China and the US are large countries with possible regional differences in terms of their cultural values and moral philosophy (Ralston, Kai-Cheng, Wang, Terpstra, & Wei, Reference Ralston, Kai-Cheng, Wang, Terpstra and Wei1996). In this study, we did not consider sub-regional differences within China and the US. Future studies that consider intergenerational differences and sub-regional variations in values orientation will provide more sophisticated findings about the evolution of international business ethics.

CONCLUSION

Although it is well accepted that business ethics may vary across national contexts through many cross-cultural studies, little is known about how business ethics in a specific culture evolve over time. In particular, research has been scarce to investigate the change in business ethics in a cross-cultural and cross-temporal setting at the same time (Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Ralston and Crittenden2012). Drawing on convergence, divergence, and crossvergence perspectives on values evolution, this study examines the evolution of business ethics in China and the US between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s. Our findings provide significant insights into cross-cultural evolution in managerial ethical decision-making and moral philosophy.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The questionnaire, data, and replication code used in this article have been published in the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/62PY4).