The world we have created is a product of our thinking;

it cannot be changed without changing our thinking.

Albert Einstein

Robert Gordon once said famously, “things could be otherwise.” … For [his] generation the realization that law is “socially constructed,” felt liberatory[:] they had been schooled in an orthodoxy that presented law as “objective” and “neutral” … For my generation, “socially constructed” meant something entirely different. It meant that things were really (really) hard to change. The question of how you do that … remains an interesting question. Footnote 1

Pierre Schlag

1. Introduction

The way international law changes, and the way it is made and unmade, depend on what one takes international law to be to begin with, and where one looks for it: in rules, in facts and actions, in minds.

To the questions ‘When and how does international law change?’ and ‘When and how is it made or unmade?’, legal formalists likely would respond in the register of the forms of the law. ‘It’s the texts, stupid’, they might grumble in exasperation.Footnote 2 They likely would send lawyers back to black letter law technicalities. Read the rules, they would insist, and you will find the mechanisms and time references dealing with the matter. Read the secondary rules of change in H. L. A. Hart’s sense. And so, the search would be on for references to state practice and the formation of customary rules, sunset and survival and grandfathering clauses, cool-off periods for international dispute settlement, stabilization clauses in international investment agreements, relevant dates for state succession, ratione temporis considerations for matters of applicability and jurisdiction, sundry rules of international legal procedures with references to ‘critical dates’ and time limits.

A modern legal positivist (one trained, in the English-speaking context, in legal positivism after the Hart-Fuller debate of 1958) would interject: Hart’s rules of recognition, just like his other secondary rules, are matters of social fact, she would recall.Footnote 3 International legal change is an affair of societal and institutional practices about and around legal norms. Observe these practices, the social facts and not just the texts, she would insist, and you will see the real dynamics of international legal change. Nico Krisch recently took the matter to heart, and identified five paths of change in international law through social facts: the state action path (‘when states modify their behaviour and make corresponding statements’); the multilateral path (when ‘change is generated as a result of statements issued by many states within the framework of an international organization’); the bureaucratic path (through ‘decisions or statements produced by international organizations in contexts that do not involve the direct participation of states in the decision-making process’); the judicial path (change through ‘decisions and findings of courts and quasi-judicial bodies’); and the private authority path (where ‘change follows statements or reports by recognized authorities in a private capacity without a clear affiliation to or mandate from states or international organizations’, typically taking the form of ‘the production of technical manuals, standards, and regulations’).Footnote 4 These are the real sites of change, he argued. The secondary rules of change as text matter much less empirically than formalists think, he maintained.

The first approach, based on formal rules, is the ‘law in books’, as Roscoe Pound had put it.Footnote 5 The second approach he would call the ‘law in action’,Footnote 6 or Eugene Ehrlich the ‘living law’.Footnote 7 Each, as we have just seen, has its own modalities of change. This article concerns itself with a third category, the law in the minds, and in particular international law in the minds; it too has its own modalities of change.

International law, like all law, can be said to exists only in our heads; the rest is manifestations of what is going on in our heads, materializations of ideas, thoughts, and beliefs about international law. The question for this article is: how are those likely to change?

Political scientists interested in institutional change would argue the question matters – and that it matters now. Mark Blyth contends that formal rules and social practices are crucial structuring factors of institutional change, but they do ‘not explain why [and when] the new equilibrium takes the form that it does’. Footnote 8 New thinking, new ideas need to occur, and then the time must be ripe for the translation of these ideational changes into institutional changes: ‘Under conditions of great uncertainty’, Blyth writes, ‘the politics of ideas becomes increasingly important’, because ‘ideas make institutional construction possible’. Footnote 9 (International law in its ‘law in the books’ and ‘law in action’ dimensions is a social ‘institution’ in that sense.Footnote 10 ) In other words, in periods of crises and marked uncertainty (like now, arguably), ideas become particularly important because institutions become particularly susceptible to ideational influence.Footnote 11 If ideas particularly matter, so should understanding how they shift.

This article moves in four parts. The first (Section 2) seeks to deconstruct the habit of searching for international law only in rules and social facts; it recalls that international law only really exists in our minds, as a noetic unity. Section 3 then suggests a general sketch of international legal change which accounts for the importance of ideas. It thereby introduces five layers of factors, presented in Section 4, which influence how ideas shift: logic and evidence, emotions and consciousness, market opportunities for ideas, the organizational base supplying resources, and overall economic and political forces. Section 5 zooms in on market opportunities for ideas and discussed five factors which shape them: the shift of paradigms based on their explanatory power, the vicissitudes of schools of thoughts, the formation of epistemic subfields, the different capitals of influential individuals, and beliefs. These are further paths of change in international law – paths of ideational change.

2. International law in the minds: Law as a noetic unity

It would be habitual in international law to search for international law only in rules and social facts. These are the places where one looks for the making, the changing, and the unmaking of international law, to identify specific ways in which they occur.

And yet rules and social facts are only manifestations of international law. It itself only really exists in our minds.Footnote 12 International law, like all law, is a socially constructed noetic unity. The point is not to suggest that rules and social facts do not matter; they obviously interact with what is in our minds. The point is that if rules and social facts change in specific ways, so does the thinking. General theories of international legal change should include the distinct ways in which the things in our minds evolve, how ideas and thoughts develop.

To say that international law is a noetic unity means that it is as a totality of related parts (a ‘unity’) created by mental apprehensions – the noun ‘noesis’ refers to purely intellectual apprehensions and the adjective ‘noetic’ means relating to mental activity or the intellect. Paul Bohannan wrote of ‘a noetic unity like law, which is not represented by anything except man’s ideas about it’.Footnote 13 Paul Amselek referred to ‘law in the minds’ as the only kind there is.Footnote 14 Philip Allott, in a discussion about international law more specifically, argued that ‘law exist[s] nowhere else than in the human mind. [It is a] product[] of, and in the consciousness of, actual human beings’.Footnote 15 Compare law to a rock, for instance. The rock exists both as an object in the natural world and as an object in our perception of it – as a ‘phenomenon’ in the phenomenological sense in our noetic experience of it. Law, however, exists only in our noetic experience of it. The rock both exists in the world of objects and in our noetic experience of it, while law only exists in our noetic experience of it. The rock will not ‘care’ whether people think about it or not. Law will ‘care’ very much, to the point of disappearing if it is thought away, ignored by enough people.

To say that international law is a socially constructed noetic unity means that it does not exist outside of a collective exercise of reason, a collective noetic experience. Consider the rules of grammar, also a noetic unity and used as a standard illustration of the overall notion, here by Paul Hoyningen-Huen:

an individual as such is unable to change the rules of grammar; an individual, by systematically breaking the grammatical rules, only leaves the respective language community but does not change its rules. Likewise, an individual by himself or herself cannot change the world structure that is inherent in scientific or everyday language. Footnote 16

Or consider money: in the world of objects a banknote is a piece of paper; in our collective noetic experience it is money. Property,Footnote 17 borders,Footnote 18 states,Footnote 19 deities in their specific cultural moments are other examples. Footnote 20

These noetic unities have significant real-world effects, so that the thinking, and the understanding of the thinking, is far from being cut off from practice. How we perceive, account for, and communicate about the world, how we behave in it, is influenced by these noetic unities. They have consequences on the material world, in the world of objects. Collective thoughts of ‘law’ create everything from borders to police officers, from the signing of international conventions to the taking of actions led by a sense that one has to follow legal rules in the name of the authority of the thought called ‘law’. All of it is created by our thinking about it, so that, in the words of Hoyningen-Huen, ‘the subjects of knowledge contribute to the constitution of the objects of knowledge (by means of “paradigms”) insofar as they structure the world of these objects’. Footnote 21 The real-world effects of noetic unities are very much at the heart of the current article. When the thinking about international law changes, the real-world effects of international law may well change too.

The point that international law only exists in minds is obvious when one thinks of it. But thinking of it in the first place requires work. It requires work because it goes against an ‘epistemological sacred’ – a particular kind of epistemological obstacle where something is taken to be so sacred that it feels outrageous to question it.Footnote 22 Arguing that international law exists only in minds appears to question its real-world effects, to cast doubt on whether it can be a ‘tangible’ obstacle to behaviour, to query the centrality of international legal texts to the ‘faith’ of international law, and in the end to defeat the fight for international law.Footnote 23 This can easily seem ethically obtuse, backward, and cynical. This in turn can easily elicit outrage. And outrage, as sociologist of thought Randall Collins puts it, is the way in which the sacred constrains understanding; that is the point when doubts, and other troublemakers, are ushered to the door.Footnote 24

Nico Krisch makes mostly the same point: ‘many legal commentators will insist that actual change in law only occurs if it meets more exacting requirements’.Footnote 25 If one wants to change international law, it has to be all about or through authoritative texts. Anything else would seem outrageous. Tolerance can be had for social practices (Krisch’s whole point) and for reifications of legal thought, as Pierre Schlag would put it, such as an identifiable professional corps, determinate legal institutions, and recognizable ritual sites.Footnote 26 But thought itself, and much less only thought, is trickier.Footnote 27 For better rhyme and reason, the model of international legal change discussed in the next section will thus include all three.

A final caveat needs to be entered in this discussion about international law as a noetic unity. When we speak of international law in our minds, our minds do two things about international law: they create it and they study it. That separation should neither be radical, nor should it be denied. Making, unmaking, and changing international law through thinking is not the same thing as studying it; but, yes, the two are in tension. To be precise, the distinction is not a strict either/or one; it corresponds to two poles entertaining dialectical relationships of mutual influence; and the distinction is not a binary on/off one but a gradual one. Yes, Andrea Bianchi argues that understandings of international law ‘do not offer subjective explanations of a reality that has a discrete and objective existence. They constitute the reality they intend to describe by representing it and constructing it on the basis of their own presuppositions and theoretical tenets’. Footnote 28 But no, not really: constituting a reality and describing it are analytically separate things (dialectical relationship of mutual influence notwithstanding); the fact that the view from nowhere does not exist does not entail that the object of study is entirely predetermined by the situatedness of the subject of study, and vice versa. The object of study and the study of the object are not coterminous, not analytically and most likely not empirically. (In the idiom of Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment, the person who opens the box is not the cat.Footnote 29 ) International law, as a noetic unity, is created and shaped by thinking, but the object thus created (even if it is ‘just thoughts’) can be studied from a relatively external perspective. From that perspective, the object of study is something which does have a discrete and objective existence, even if it is shaped by the prefigurations of the subject of study. Footnote 30 (I can study the thoughts of someone else without substituting these thoughts with mine, even though there will be some projection.) The prefigurations of the subject are in turn influenced by the object. (I may be influenced by someone else’s self-declared thought patterns when I study these thoughts.) So that the subject’s perspective is ‘moderately external’, as Michel van de Kerchove and François Ost put it, as it takes into account the internal perspective of the legal actors.Footnote 31

3. A general sketch of international legal change

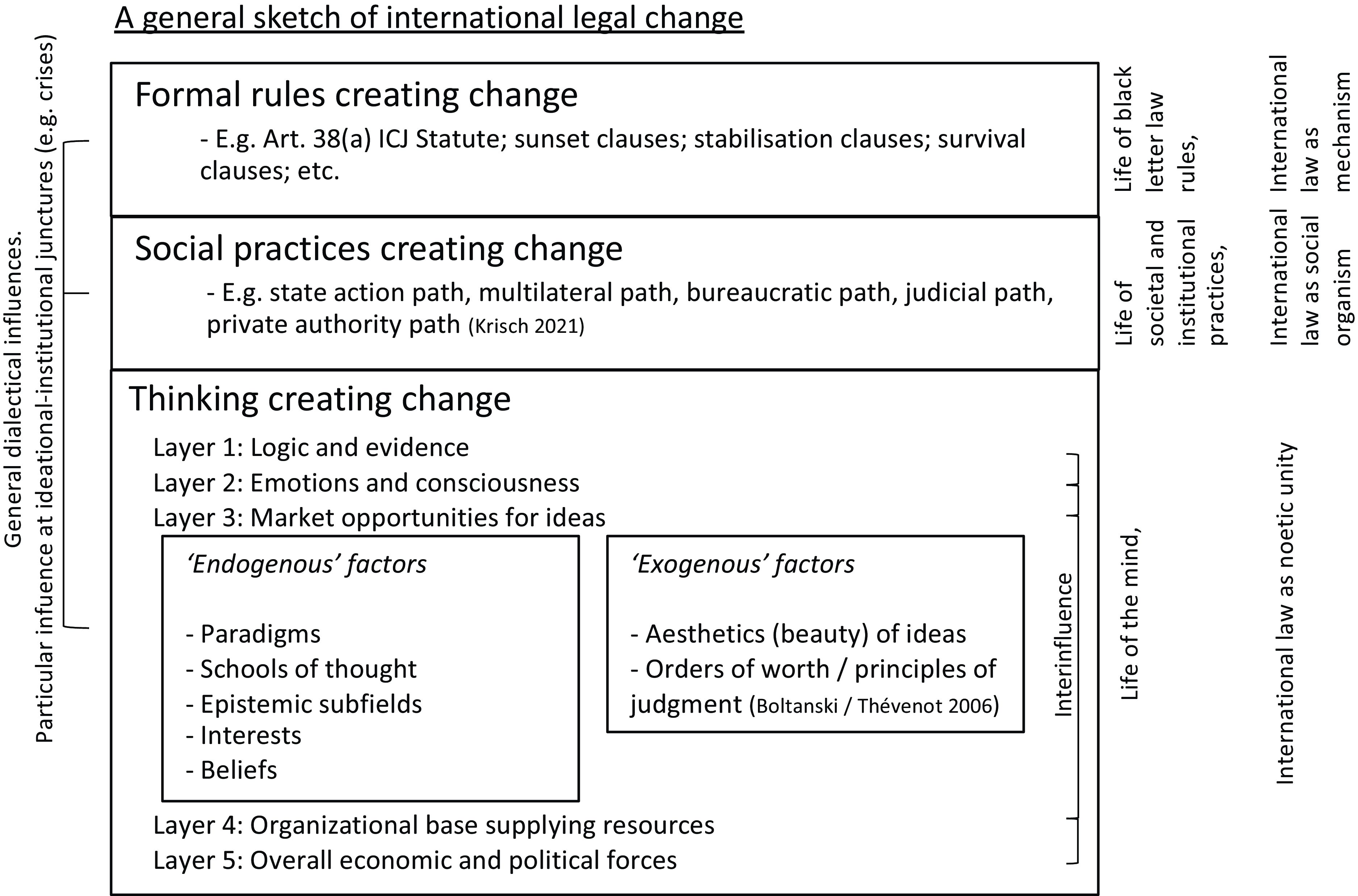

A general sketch (it is not quite a general theory) of international legal change might look like this chart (Figure 1):

Figure 1. An overview of the different elements influencing international legal change.

The core distinction on the chart is between black letter law, social practices, and thinking. Footnote 32 Clearly, and at the risk of repeating myself, black letter law and social practices involve thinking, and international legal thinking can barely be done without any reference, not even implicit or subconscious, to formal rules and to social practices. Footnote 33 But it is not because they are related and entertain mutual influences that they cannot be distinguished; it is more of an analytic than a synthetic distinction, analytically separating formal rules which determine, condition, and drive international legal change, social practices which do the same, and thoughts and ideas which again do the same.

The connecting lines on the left suggest interactions between the three blocks (rules, social practices, ideas). These interactions are thought to be dialectical influences – one passes over into the other and influences it and is influenced by it in return in the same way. The connecting lines also suggest ideational-institutional junctures. These are the points in time at which new ideational changes are most likely to translate into a concrete effect on institutional setups. When the thinking changes, it leads to change at certain privileged times in societal and institutional practices about black letter norms of international law and/or to change in the letter of these norms. According to Mark Blyth and as already said, these privileged times are crises and periods of marked uncertainty. Footnote 34

The first block, ‘Formal rules creating change’, is about international law being changed by amending treaties, redirecting custom, etc., as constrained and influenced by black letter international legal rules. That kind of change, according to black letter rules, is effected according to modalities and temporalities largely determined by the black letter rules: established legal practices, sunset clauses, etc. The chart, on its right-hand side, calls this ‘the life of black letter law rules’, or in longer form ‘the life of international law according to black letter law rules’. It takes as its substrate international law as a mechanism, which follows mechanical-like changes. (This, as the rest here, is a simplified, chart-like, representation, of course.)

The second block, ‘Social practices creating change’, represents international legal change separately from variations to the formal, black letter legal rules. Nico Krisch recalls that ‘the absence of legislative mechanisms on the international level and the high doctrinal thresholds for change through treaties or customary law’ tend to, first, create ‘a tension between … stasis and dynamism’ and, second, exhibit an ‘apparent tendency towards stasis’.Footnote 35 But this is only part of the story, he argues. If one looks not at form but content, not at rules but at action, the resulting picture is one of ‘frequent and rapid’ change ‘created by social actors and their practices relatively independently from doctrinal representations’.Footnote 36 This shows how ‘law often changes in and through social practices in ways not easily reflected in the “law on the books”’. Footnote 37 This, he says, is ‘the social life of international law’; it follows the five paths mentioned in the introduction to this article. Footnote 38 The chart, on its right-hand side, calls this ‘the life of societal and institutional practices’, or in longer form ‘the life of international law according to empirical societal and institutional practices’. These practices follow certain temporalities, have a certain (social) pace, which could most likely be identified in reference to Krisch’s five paths of change. This representation of international legal change takes as its substrate international law as a social organism.

The third block, ‘Thinking creating change’, is about noetic processes. This refers to when and how international law changes through a collective exercise of thought, as a noetic unity. This has its own elements of constraint and influence, which shape the thoughts being thought and thus institute different modalities and temporalities for international legal change. Loosely inspired by Randall Collins’s sociology of philosophies, these elements are presented here as five successive layers of influence, from logic and evidence to the overall economic and political forces, which we shall discuss in the next section. Footnote 39

4. Five layers of constraint and influence on international law in the minds

The factors directly constraining or influencing the thinking about international law can be organized in five layers. None of them work alone. Each affects at least one other layer, and several entertain dialectic relations of mutual influence. The five layers together form some of the main drivers of change, or absence of change, in the thinking about international law. It might be called ‘the life of the mind’ of international law. It takes as its substrate international law as a noetic unity, as discussed above. The following pages examine what is found on each of these layers.

4.1 Layer 1: Logic and evidence

The first layer is logic and evidence. Unremarkably, thinking about international law can change through logical thinking and the discovery or understanding of new evidence. This itself, being straightforward, deserves no particular attention here. It bears mentioning though that logical thinking, in law, is quite unlikely to ever be pure, unaffected by the other layers of constraint and influence on international law in the minds, operating in isolation or in a vacuum. It is debatable whether pure logical thinking tout court is possible at all.Footnote 40 It seems quite certain that thinking involving language, such as legal thinking, cannot.Footnote 41 When it is said that words, such as legal terms, have an ‘objective meaning’ or a ‘logical meaning’, these adjectives are taken in a different sense than in the philosophical distinction between objective and subjective or in the field of formal logic, because meaning of words, and any other signs, are based on a ‘silent agreement between participants in a conversation’, as Gadamer would put it,Footnote 42 and that silent agreement is based on many other elements, some of which would feature on the layers discussed hereafter. None of this of course means that logical relations between thoughts does not constrain or influence the thinking of international law; the point is simply to clarify that it does not operate in isolation or vacuum from the other elements on the other layers.

4.2 Layer 2: Emotions and consciousness

The second layer is emotions and consciousness. A ‘direct’, immediate, and purely objective understanding of the world is never possible.Footnote 43 Access to the world, to evidence, the processing of information and ideas – this is always, inevitably, mediated and influenced by emotions and various psychological drivers, as well as different things that make up consciousness. As a review from a leading research group in affective science put it laconically: ‘Reason and emotion have long been considered opposing forces. However, recent psychological and neuroscientific research has revealed that emotion and cognition are closely intertwined … emotional responses modulate and guide cognition … Emotion determines how we perceive our world.’Footnote 44

The same mediated access to the world applies to legal thinking. Emotions and consciousness influence the practice of (legal) logic and the identification and appreciation of evidence in legal thinking. Legal thinking is inevitably emotional thinking; it is more broadly psychology- and consciousness-influenced thinking.

There are interesting encounters between international law and emotions in the literature. For instance, Andrea Bianchi and Anne Saab showed how fear influences international law-making (rule-making, decision-making, and other forms of international legal change).Footnote 45 Anne Saab has discussed how fear more specifically is used by and shapes climate change discourses. Footnote 46 Emily Kidd White has done work on the role of emotions in structuring the object of international law, separate from the subject studying it: she argues that rational, classical approaches to international law put the focus on contingency, treaties, ownership, and jurisdiction, while an approach grounded in emotions would see bodies, precarity, relations, desires.Footnote 47

The approach taken here puts the focus somewhat elsewhere: on the subject studying international law and what emotions likely traverse him. Not the emotional objects she studies, like precarity or terror, but the emotions of the subject himself.Footnote 48 This would cover, for instance, the question of why emotionally we do the ideational construction of international law that we do, and what emotions influence our epistemologies and thus the manufacture of our scholarship. Footnote 49

This brings up Martha Nussbaum’s work, when she writes that emotions must:

form part of our system of ethical reasoning, and we must be prepared to grapple with the messy material of grief and love, anger and fear, and in so doing to learn what role these tumultuous experiences play in our thinking about the good and the just.Footnote 50

Nussbaum focuses ostensibly on ethics, on emotions as judgment, while I focus on legal epistemology, but epistemology can also be understood as a form of judgment: the knowledge act, the decision to know, can be seen as judgment.Footnote 51

On consciousness, Raymond Williams’ ‘structures of feelings’ come to mind. ‘[T]he endless comparison that must occur in the process of consciousness between the articulated and the lived’,Footnote 52 he explains, tends to reveal a tension, a ‘tension between the received interpretation and practical experience’.Footnote 53 This tension is ‘often an unease, a stress, a displacement, a latency’Footnote 54 between what is and can be articulated and what is felt and experienced: these semantic inconsistencies point to structures in thinking, structures which cannot be reduced to currently existing, precipitated social semantic formations. These structures remain structures of…feelings, rather than thought, because they are not yet articulated. They are rather ways of thinking which vie to emerge, though already influence the articulated thinking.Footnote 55 This speaks to the distinction between access-conscious mental states (which is representational) and phenomenal consciousness (subjective experiences which overflow cognitive access).Footnote 56

4.3 Layer 3: Market opportunities for ideas

The third layer, more pragmatic, comprises market opportunities for ideas. This will be the focus of the balance of this article after this section.

An idea (perhaps one reached through logical thinking based on new evidence and mediated by emotions and phenomenal consciousness) will flourish, spread, become influential, and change the thinking in a field if it is ‘received’ in the field. Footnote 57

One might think of an idea being ‘received’ in a field by analogy with the meaning of a text being received by an audience. An interesting take on the matter is Hans Robert Jauss’s ‘reception theory’ in literary theory, itself inspired by Hans-Georg Gadamer’s hermeneutics.

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s core argument about hermeneutics, as already alluded to above, was that interpretive acts are always contextualized, the meaning given to texts depending on social, historical, and other contexts, on what questions the interpreter asks of the text. Footnote 58 Hans Robert Jauss took the idea further and developed a ‘reception theory’, which puts more accent on the acceptance of meaning and on the historical evolution of the meaning given to a particular text, Footnote 59 the classical example being how foundational religious texts were understood differently over the centuries. Footnote 60 In economic terms, to stay in the idiom of market opportunities, one might say that the questions the interpreter asks of the text (Gadamer) and the willingness to accept certain meanings given to a text through history (Jauss) are ‘demands’ (as in ‘supply and demand’) on the market for meanings. The same way of thinking can be extended, not to meanings given to texts, but to ideas.

In that sense, an idea likely will be received in a field if it resolves a question which was asked of the thinking, and for which there is willingness of acceptance. An idea for which there is a demand.

What factors determine the demand is a complex matter. One can roughly distinguish two types of factors: general, exogeneous ones, which would tend to be present much beyond the field of international law, and somewhat more specific, endogenous ones which are less connected to the world beyond international law. The difference between the two is a matter of degree. This article will seek to unpack some of the core endogenous factors determining the demand for certain ideas in international law. But before we turn to this, let me rapidly mention two exogenous factors.

The first exogenous factor is aesthetics. Aesthetics in the sense of beauty, not in the sense of the underlying principles of a person’s work.Footnote 61 Beauty attracts. As an end in itself that gives satisfaction, Kant would say.Footnote 62 As a means to the end of biological survival and evolution, naturalistic psychology would suggest.Footnote 63 More generally as a ‘force in awareness, creativity, and survival’, medical scientists would argue.Footnote 64 But let us leave aside the question of why exactly beauty attracts. The fact that it does attract, Ariel Conomos recently showed, also applies to beautiful ideas, beautiful ways to resolve problems, beautiful theories: scientists, academics, lawyers, mostly everyone has a preference for beautiful ideas.Footnote 65 Intellectual performance is judged in part as an artistic performance. There is such a thing as an aesthetic of knowledge, beautiful knowledge. Simple theories, uncomplicated solutions to problems tend for instance to be considered aesthetically pleasing. The beauty of an idea, of a theory, determines its worth on the market for ideas. There is a demand for them. It would be interesting, but beyond the scope of this article, to examine how criteria of beauty have evolved for ideas and thoughts in the general scientific domain, and how that evolution has been matched in international law.

The second exogenous factor is captured by Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot’s theory of justification.Footnote 66 An idea may be received in a field, it was argued above, if it resolves a question which was asked of the thinking. That resolution must be accepted. The solution it offers to a conundrum, for instance, must be accepted. Most questions can be interpreted, at some juncture in the reasoning about them, as a dispute; a dispute between solutions. (Recall the point above about knowledge as judgment.) For the solution to a dispute to be accepted, it needs to be justified, Boltanski and Thévenot would in essence say. And that justification, the point where ‘because…’-type regressions stop, depend on what they call ‘principles of judgment’ or ‘orders of worth’. Principles of judgment for justifications also exist in intellectual networks, where they become principles justifying and validating ideas. An idea may be justified and validated, or ‘received’ in the language from above, there may be ‘demand’ for it, because it elicits amazement and awe; or because it smacks of responsibility and honesty; or because it comes from a place of visibility, popularity, or fame; or because it deals in solidarity; or because it contributes to prosperity; or because it is efficient and reliable.Footnote 67 Such principles of judgment seem rather to traverse large swaths of the population and to be determined by culture and epoch and other social factors; they seem unlikely to be specific, endogenous to international law.

Endogenous factors, those that this article will concern itself with, which are taken to be more specific to the field of international law than the two just discussed, are taken to be: the shifting of international law paradigms; the rises and falls of schools of international legal thought; the constitution of epistemic subfields within international law: the shifts in material or ideological or other interests of the field’s important individuals; and the currents of beliefs in the field. The evolution of these five factors influences the demand for specific ideas or for kinds of ideas. This is how, ‘market opportunities for ideas … open up at particular times’, as Randall Collins puts it. Footnote 68 These five factors will be discussed in Section 5.

Before we turn to the next layer of constraint and influence on international law in the minds, one particular interaction between these layers deserves mention: how market opportunities for ideas influence the emotions and other psychological drivers of the thinker. Collins recalls that ‘Thinking is a conversation with imaginary audiences’. Footnote 69 During these conversations, the feeling of excitement (one of the psychological drivers of thinking, which orient the thinking, the holding on to an idea) felt when thinking a new thought depends on the expected reactions of these audiences. The feeling of excitement may be triggered by the ‘market opportunities’ that the imaginary audiences offer: ‘Eureka, I found an idea which will be bought into! Let me hold on to that.’ And the audiences react, offer market opportunities, according to the intellectual networks that traverse them, intellectual networks which spread and regroup according to paradigms, schools of thought, epistemic subfields, interests, and beliefs.

4.4 Layer 4: Organizational base

The fourth layer consists of the organizational base supplying the material resources for the thinking and thus sustaining the intellectual networks.

Some forces push, others pull. Inertia pulls, impedes change. The organizational base of a field is likely to create inertia, as Howard Becker famously showed. His point was that simple material elements can constrain and organize the social situations in which social things get made, often slowing them down. He illustrated his point with classical music: bookkeepers, accountants, lawyers, unions, elementary and secondary schools teaching rudiments of music, state and city funding, as well as the instruments and the scales – all rather unsuspected elements which come together to slow down change in the music itself.Footnote 70 Similar material elements influence international legal thinking, often increasing inertias: universities, publishers, funding agencies.

These are the more conspicuous elements. Pierre Schlag describes more silent ones:

[i]deas are very hard to come by. They require struggle not only against the various orthodoxies that compose the university, but a struggle against the various social and political inertias and momentums that comprise and quietly maintain these orthodoxies. Many of these inertias and momentums arrive innocently enough, bearing names such as “research agenda” “faculty workshop,” “conference panel” “law review article,” and so on. Footnote 71

Quiet as they are, these are perhaps the most workaday, and thus insidiously powerful, reifications of the life of the mind (at the least the life of an academic’s mind).

Schlag goes a step further, towards yet more hushed constraints and influence. He argues that these reifications are caught up in a particular ideology and political agenda: ‘Very quietly, the liberal university has been colonized by neoliberalism.’ Footnote 72 Neoliberalism in the sense of ‘the inculcation of the forms, idioms, and logic of business actors in the practices and institutions’ Footnote 73 – the practices and institutions of, in this case, the universities, publishers, and funding agencies. That law faculties in particular, where much of the thinking of international law occurs, have been colonized by the weltanschauung and reflexes of business actors seems obvious enough. (The use of ‘market opportunities’ for ideas in this very article is not exactly a counterexample.) This link to neoliberalism takes us to the fifth layer on the chart.

4.5 Layer 5: Wider political and economic forces

The fifth and last layer is composed of the wider political and economic forces which feed the organizational base and often influence the thinker directly. This would be the level of Pierre Bourdieu, for whom professions, certainly including the profession of thinking international law, are ‘the social product of a historical work of construction’, Footnote 74 which is both based on and creates ‘social structures and mental structures’. Footnote 75 This would also be, broadly, the level of Antonio Gramsci’s idea of hegemony, in the sense of the intellectual and moral leadership embedding a ruling class across society.Footnote 76 And of Michel Foucault’s épistémè, in the sense of the subjective parameters of an epoch which define the conditions of possibility of all knowledgeFootnote 77 – something like a paradigm in Kuhn’s sense, discussed below, but much broader, across all of society. And of Ruth Benedict’s ‘patterns of culture’,Footnote 78 of Erich Fromm’s notion of ‘social character’,Footnote 79 and all manner of spirits of the ages.

Closer to international law, Geoff Gordon has shown how economic materialism, the bourgeois enterprise, and vested economic interests influence the overall thinking in that field, the thinking of that object, including how they institute a certain understanding of time for international law which helps maintain these wider political and economic forces. Footnote 80

5. Five factors shaping market opportunities for ideas in international law

Let us zoom in on what, we might say, is the closest and most specific to international legal thought: the factors which determine when and how market opportunities open up in international law for certain ideas or kinds of ideas. Arguably, logical thinking based on evidence, emotions and consciousness, the overall organizational base of international legal thought, and general political and economic forces (that is, the four other layers identified above) comprise factors constraining and influencing the thinking in parts of society much broader than the field of international law. Even the organizational base of international legal thought is not specific to it: the material arrangements within which international legal knowledge is produced are almost identical to those within which other legal knowledge is manufactured. Within the layer of market opportunities for ideas, as represented on the chart, the focus is here more specifically on factors that were called, above, endogenous to the field of international law.

5.1 Paradigm shifts: The pull of explanatory power

Market opportunities open up for certain ideas when the right paradigms, in Thomas Kuhn’s sense, come to rule the field.Footnote 81 Paradigm shifts – when a new central understanding or set of understandings replace older ones because they have greater analytical purchase – create key windows of opportunity for new ideas to come on the market.

Kuhnian paradigm shifts are common knowledge, but a brief reminder seems in order. According to Thomas Kuhn, scientific disciplines alternate between periods of normal science and periods of scientific revolution. Footnote 82 During periods of normal science, a scientific discipline, an academic field, a field of thought more generally (international law for instance) is organized around a central paradigm, a central idea or understanding, a central set of beliefs and values, which amount to rules of ‘valid truth’, widely shared by the members of the field. And then trouble comes to town. Anomalies appear. Situations in which things happen that should not happen according to the theory, are not explained by the paradigm. Typically, these situations are progressively encountered ever more frequently. The validity of the paradigm is questioned and new candidate theories (candidates for paradigm) line up in the competition to become the next paradigm. When the competition starts, the scientific discipline in question has entered a period of scientific revolution. The paradigm resists for a time by stretching its explanatory reach in increasingly less credible manners. Until it eventually gives way to a new paradigm with greater explanatory power. The new paradigm determines in turn what is valid or ‘true’ in the field, thus what thoughts can be received, thus what opportunities exist for such thoughts on the market for ideas.

Consider the recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples. In the past, a dominant paradigm in the field was the principle of state sovereignty, giving states almost complete control over their territories and populations, ignoring the rights and interests of indigenous peoples. But then, with the growing need to address historical injustices, the paradigm shifted to recognize rights to self-determination, cultural integrity, and land and resource ownership. Footnote 83

Or consider the idea that law is necessarily created by states, that international law must be made by states in order to validly count as international law – an idea increasingly doubted in the field. Footnote 84 Books and other publications assuming the existence of non-state international law were much more difficult to get accepted 30 years ago than they are now: market opportunities – here in the proper economic sense of a market for the sale of certain books – appeared thanks to a paradigm shift. Footnote 85

What we have here is a path of ideational change of international law which follows the path of change of paradigms: one which turns rather rarely but then quite abruptly.

That path of ideational change operates like a stock-type causal link, in stock-and-flow system dynamics analysis. Flow-type causal links are things like turning up the heating in an apartment. You open the valves a bit, it gets warmer, more or less immediately. By contrast, stock-type causal links are situations like friendship. A friend pulls one over you, nothing changes in the friendship – you forgive, no one is perfect, a friendship is not a tit-for-tat relationship. The friend pulls another one over you, still no change, no effect on the friendship. And then, the tenth time, the friendship is over, seemingly all of a sudden. The stock (here of disappointment, hurt, anger) reached a certain level, and then the effects took place. A stock-type causal link is non-linear: a stock of something needs to breach a critical threshold to cause change. Footnote 86 And so with principles governing the validity (or reasonableness) of ideas and marketing opportunities for ideas: a paradigm, governing the validity or reasonableness of ideas, is falsified, or otherwise shown to be lacking in explanatory power, and nothing seems to change. But at some stage, the stock of falsifications is high enough to have an effect, and then the paradigm gives way, seemingly all of a sudden. And market opportunities open up, quite abruptly, for new kinds of ideas. The problem with stock-type causal links is that it is often difficult to assess precisely how high the stock is at any point in time, and thus how much more will make it breach the critical threshold. In other words, it is often difficult to assess precisely when a paradigm will shift, thus when that path of ideational change of international law will take a turn and have an effect. Footnote 87

5.2. Competing schools of thought: The pull of groups

Paradigms change not only because a new central idea offers better explanatory power. New paradigms can also be imposed by brute force, through the power of a school of thought.

Kuhn’s theory as described above is a widespread account of the way paradigms change, but it is simplistic and idealistic. It shows an unrealistic belief in the purity of the pursuit of scientific knowledge. Footnote 88 Thinking heads are attached to the bodies of social animals, which form societies, communities, and groups, sometimes around shared ideas. Shared ideas are often reinforced within the group, which turns group membership into an epistemological obstacle because of deep-set social anxieties of exclusion. Footnote 89 Consider flat-earthers (individuals who say the earth is flat): many argue that they have found group membership, and friends, when they embraced that view, and fear that bringing their thinking back to evidence from physics will lead to exclusion. Footnote 90 Truth is easily traded for companionship.

Kuhn himself was used, against his intentions, as an icon of some of the radical student movements of the 1960s in the USA and in Germany. The idea that there can be revolutions in scientific knowledge was used as an argument to drive actual revolutions against the institutions producing scientific knowledge: the universities. Footnote 91 Protests, arsons, and other demonstrations of force were used to bring about change in the production of scientific knowledge and thus in scientific knowledge itself: change the people manning the universities, change the relative strength of schools of thought, change scientific knowledge and thus received wisdom (or ‘truth’ in the layperson’s sense). Footnote 92 Bourdieu would later write: ‘I have attributed to Kuhn the essential part of my own representation of the logic of the [scientific] field and its dynamic’; Footnote 93 that is, a logic characterized by a focus on clashes of social forces in the production of knowledge, which made Bourdieu ‘one of the great heirs of the Western Marxist tradition’. Footnote 94 Kuhn’s emphasis on the idea that scientific knowledge is not an immutable objective truth, but rather a matter of changing perspectives, facilitated the understanding of that knowledge as the contingent result of social forces. This famously later played tricks on Bruno Latour, when he first sought to demonstrate how scientific facts are socially constructed, Footnote 95 only to find his argument soon distorted to mean that scientific knowledge is a social opinion like any other Footnote 96 (in an obvious reduction of the sliding scale of truthlikeness Footnote 97 to a binary opposition truth vs. opinion).

In short, new theories taking hold, being received on the market for ideas, are not necessarily always ‘scientifically’ better than the older ones they are replacing. Science does not inexorably progress, because of human nature and the diversity of things that people really try to achieve when they put forward or receive theories. Paradigms can also be imposed like one imposes a new political regime. A paradigm is ‘better’ than another, prevails over it, because the school of thought built around it is stronger than the other paradigm’s school, and can thus impose it. Footnote 98

Imposition of a paradigm can take the form of an inundation of a field with publications by the school of thought’s gang mates, relentless organization of conferences around the paradigm, the launching of an academic journal taking a fitting approach, the impartation through teaching of the exclusive correctness of a particular way of thinking (with corresponding grades to follow), intra-law-faculty politics, funding of PhD students and postdocs and appointments of professors, etc.

And so schools of thought ebb and flow, each with its paradigms, prefigurations, and underlying principles of work. Footnote 99 Consider the comings and goings of formalism, constitutionalism, Marxism, the New Haven school, IR theory, the crits, the realists, the empiricists, the Helsinki school, feminist approaches, TWAIL, legal pluralism, social idealism, law and economics, law and literature, scientometrics, the grid thinkers, the reformists in their energy aesthetic, the perspectivists, the dissociativists, etc. Footnote 100 These vicissitudes increase or decrease market opportunities for ideas which fit one or the other school.

5.3. The formation of distinct epistemic subfields: The pull of specialisms

Schools of thought do not only vie for domination of a field, one to rule them all. They can also break it up into smaller subfields.

Jan Klabbers famously lamented this. Each ‘corner’ of international law, he argued, has its own ‘canons of thought…intellectual leaders and hierarchies…publication venues…institutions’. Footnote 101 This is bad, he found: ‘[t]he discipline has fragmented into different epistemic communities…also deeply divided along methodological lines. Instead of the fragmentation of international law being a concern, we should be worried about the fragmentation of international lawyers’. Footnote 102 Andrea Bianchi, by contrast, takes joy in it. His book International Law Theories: An Inquiry Into Different Ways of Thinking smacks of the freedom that has come to breathe on international legal scholarship. Footnote 103 The Berlin wall of formalist orthodoxy has finally fallen, he seems to say. Jean d’Aspremont takes a view somewhere in the middle. He sees it as a ‘growing cacophony’, causing ‘international legal scholars [to] often talk past each other’. It is not quite a worry, but it is bewildering nonetheless, he contends: ‘It is as if international legal scholarship had turned into a cluster of different scholarly communities, each of them using different criteria for the ascertainment of international legal rules.’ Footnote 104

The creation of subfields is an ideational path of change of international law. If international law means different things to different people grouped in subfields, it is a different thing in each of the subfields. D’Aspremont’s quote recognizes as much: ‘different scholarly communities…using different criteria for the ascertainment of international legal rules’. Footnote 105 Legal realism has been making this point for 120 years; Footnote 106 here it is extended to a subfield of international law, taken to be coherent within. It is a path of change because when an epistemic field breaks up into new subfields, new noetic constructions of the object are likely to emerge. When new subfields emerge using new criteria for the ascertainment of international legal rules, for example, new international law is made: a new noetic unity is created with a somewhat new shape. For a parallel, consider how cryptocurrencies became money. A subfield of finance developed new criteria for the ascertainment of monetary characteristics, and new money was created.Footnote 107 A new noetic construction of money had emerged, specific to subfield (it later spread). The emergence of a new subfield of international law, a new distinct community of individuals who think about international law in a distinct way and according to a different paradigm with a different epistemology and working with a different aesthetic – that may well mean the emergence of a new set of norms (or other elements) deemed to amount to norms (or other elements) of international law.

5.4. The evolution of interests: The pull of capitals

What is good for a person is an incentive for that person to see certain things in a certain way, through selective attention, or at least to retain certain accounts of these things. One’s interests determine one’s epistemology.

More precisely, one’s epistemological views are credibly determined not only by one’s epistemic reasons (reasons to believe something to be true)Footnote 108 but also by one’s prudential reasons-for-action (reasons to undertake a certain course of action, including holding on to a view, because it is in the person’s interest).Footnote 109 Applied to the current object of study, international law may be created and shaped in a certain way because of a belief that the construct is sound or ‘true’ (epistemic reasons) orFootnote 110 because it advances the interests of those who think it into being in that particular way (reasons-for-action).

Consider the case of a current or former government lawyer who has interests in promoting or sustaining the power of government – interests which can be psychological, such as making sense of one’s life; or social, such as belonging to the group of co-workers at large; or financial, such as staying on good terms for advisory work and other appointments. These interests, the pursuit of these capitals,Footnote 111 become prudential reasons-for-action for an epistemology that prevents the recognition of non-state actors as creators of customary international law, for instance.Footnote 112 If one’s interest is that governments stay strong, one’s epistemology is plausibly such that only governments can make law, that only states can create and change norms of international law. And so it would be unwise, and empirically unlikely, for states to elect to the International Law Commission, for work on the identification of customary international law, someone who does not have a state-centric epistemology, which in turn can partly be determined by an individual’s utility function.

These interests are not immutable. When those of the individuals who dominantly shape the thinking about international law change, their epistemology is likely to change, and international legal change is likely to be affected. The identification of such change in interests in the relevant individuals is one predictor for international legal change. For instance, academic salaries in certain countries are such that international legal thinkers are led to embrace a certain epistemology, state centric and business friendly. A change in academic salaries may cause a change in that epistemology and thus in international law. The notion of market opportunities for ideas is taken here to its most material conclusion: who can ideas be sold to, literally.Footnote 113

5.5 Changes of beliefs: The pull of ideologies

International lawyers are not immune to ideologies. There are not many market opportunities for ideas which go against deeply held beliefs. Beliefs constrain epistemologies, including in international law.Footnote 114

Consider the belief that law is good, an unconditional moral-political positive, always better than the alternative. ‘Wherever law ends, tyranny begins’, John Locke said. Footnote 115 Or as Jerold Auerbach would put it, law is the ‘glorious triumph…over inferior forms of communitarian extra-legal tyranny’. Footnote 116 (As if no tyrant had ever used a legal system to strengthen their grip on power.Footnote 117 ) There exists a strong belief that international law is good, that more international law is better than less, that international law has the solutions within itself.Footnote 118 This creates a powerful ideology, because it gives moral meaning to the profession. This easily leads to the belief that law has to actually be appliedFootnote 119 and obeyed, that it comes with deference entitlement, Footnote 120 and that it has to be enforced if not complied with. To preserve or increase the authority of international law, to fuel its entitlement to be deferred to: these are common cardinal points on the moral compass of international legal scholars. To the point that even just questioning it creates risks of being pushed out of the community of international lawyers and into that of legal philosophers.

Or consider the belief that states are good. Léon Duguit and Hans Kelsen admitted that:

we believe to have serious reasons to be convinced that the only means to satisfy our aspiration to justice and equity is the resigned confidence that there is no other justice than the justice to be found in the positive law of states. Footnote 121

This contributes to the axiom, and the difficulty in changing the axiom, that only states can make international law: It closes market opportunities for related ideas, and thus partakes in the collective construction of the noetic unity.

6. Conclusion

International law is an idea. One that altered the world. It is a big idea, one composed of a constellation of smaller ideational elements. How and when do these elements rise and fall, collide, conflict, and combine? Because when they do, international law changes, and so do the ways in which it alters the world. This is what this article has been after. It sought to identify international law’s paths of ideational change, and more precisely how the market for ideas shapes it.

Market opportunities for international law ideas are an important yet rarely discussed factor of international law change. International law, like all law, is a noetic unity, something created by thinking it into mental being; it exists in the minds. This makes the practice of that thinking, its epistemic manufacture, a valuable element of attention if one wants to understand how international law evolves.

What came of the attention is that international law is made, changed, and unmade according to searches for better accounts of its elements, the respective forces of its schools of thought, parallel reconstructions of the same overall object in different corners of the domain, the preservation or increase of the thinkers’ different capitals, and beliefs among international lawyers. These factors are in turn further constrained and influenced by logic and evidence, emotions and consciousness, the organizational base of the thinking, and wider economic and political forces. And all of it interacts with international law rules and the social practice of these rules, in a complex yet mappable system.