Technically, the only criterion for a surrogate mother is a healthy uterus, and the only criterion to create a family is expressing the intention to parent in a contract, along with an ability to pay for the “exchange.” Where deemed legal, surrogacy contracts are framed as dispassionate transactions for services and labor (Culliton v. Beth Israel MA 2001; Johnson v. Calvert CA 1993; U.P.A. §801(e) 2000, 2002; 750 ILCS 47). Once technology separates the baby from the pregnancy, “women are no longer necessarily the mothers of the children they carry within,” they are solely “a contractual agreement” (Reference Rothman, Rothenberg and ThomsonRothman 1994: 264). But is a surrogate mother really “just the oven,” free from emotional attachments, delight, or resentment, even when she is motivated to assist a desperate, infertile couple willing to pay for her trouble? (Reference HatzisHatzis 2003).

Despite a rich literature in law and society embracing contracts as exchange relations, empirical work has yet to address their emotional dimensions. Surrogacy contracting offers an ideal context to highlight this oversight. Emotions are culturally and discursively experienced through individuals embedded in social structures (Reference BandesBandes 1999; Reference Turner and StetsTurner and Stets 2005). In her study of how amniocentesis changes the experience of motherhood, Barbara Katz Rothman details how women awaiting test results manage to keep anxiety under control, at a cost. A pregnant woman “may feel she has to keep distance, emotionally and pragmatically, from the baby,” and thus experiences “a very tentative relationship to the fetus” (Reference RothmanRothman 1993: 102–103). In surrogacy, that “tentative” relationship between mother and child turns to certainty of separation, requiring more emotional “distance.” Why and how do lawyers, with the help of other professionals, manage the complex range of emotions experienced by surrogates and parents during and after contract performance?

In this article, I draw on 115 in-depth interviews and content analyses of 30 contracts to address the interface of law and emotions in exchange relations. Additionally, I map a previously unknown terrain for the very first time: surrogacy contracting. I unpack the legal interests, risks, and social relationships that are situated at the nexus between a surrogate's womb and the hopes of “intended” parents who contract for her labor within a conflicting legal landscape. I explain why and how lawyers who specialize in assisted reproduction, with the help of matching agencies and counselors, anticipate and tactically channel a variety of emotions in surrogates and intended parents before, during, and after the baby is born. I establish that a web of “feeling rules”Footnote 1 formalized in the contract along with informal strategies like “triage” are intended to minimize attachment, conflicts, and risk amidst a highly unsettled and nascent terrain. These rules and strategies are then shared and embraced among reproductive professionals, forging new emotion cultures. However, I show that feeling rules go above and beyond rationalized risk assessments.

Surrogacy offers a strategic site in which to investigate how law shapes feelings, and conversely, how feelings shape law. I introduce this phenomenon as the legalization of emotion, a consequential process that may be occurring throughout contemporary American society in a variety of exchange relations.

Background on Reproductive Technology and Surrogacy

Surrogacy contracting offers a unique opportunity to understand how law operates to manage feelings for a variety of reasons. First, surrogacy is a process whereby a woman bears a child for another person, typically in exchange for consideration by contract (Reference Kindregan and McBrienKindregan and McBrien 2011: 151; U.P.A. §801(e) 2002). In traditional surrogacy, the surrogate uses her own egg and thus, is genetically related to the child she gestates (Id.). A gestational surrogate uses the egg of another person, a third-party “donor,” to birth a child (Id.). Scientific and medical advancements like egg donation, the cryopreservation of embryos, and success in gestational surrogacy spurred private bargaining and use of technologies in the absence of federal regulation (Reference Crockin and JonesCrockin and Jones 2010). Ethical debates on the commercialization of life through gamete sales and contract pregnancy persist but have not halted the boom in the family formation market (Reference Ertman and WilliamsErtman and Williams 2005; Reference GoodwinGoodwin 2010). A sharp rise in demand is fueled by increases in both biological and social infertility, as well as trends in gay parenting (Id.).

Second, within the United States, jurisdictions are still divided and undecided on the legality of paid surrogacy, which continues to be prohibited in several states and most countries around the globe (Reference LewinLewin 2014). Some states prohibit commercial surrogacy as void for public policy against “baby bartering” and the detached “manufacture” of children (In Re the Matter of Baby M 1988; Goodwin 2010; Markens 2007). These jurisdictions treat surrogacy as an invalid attempt to circumvent state adoption laws, which provide a grace period for a remorseful birth mother to rescind termination of her parental rights. Mothers are normatively expected to feel loving, nurturing, and attached to their fetus in utero, and bond with the babies they bear (Gonzales v. Carhart 2007; Reference MadeiraMadeira 2012; Reference SangerSanger 1996; Reference SiegelSiegel 2008).Footnote 2 Commercial surrogacy, which demands detachment, counters the norm. The Baby M case and its progeny provide a formal declaration that emotions like remorse are legally relevant in contracts.

Other jurisdictions characterize surrogacy as a dispassionate contract for “services” and compensation for the labor of gestation, not the selling of children in violation of international law (Reference Crockin and JonesCrockin and Jones 2010; Culliton v. Beth Israel MA 2001; Johnson v. Calvert CA 1993; Reference Kindregan and McBrienKindregan and McBrien 2011). Recognizing the increasing and elicit use of reproductive technology, California led the pack of “surrogacy friendly” jurisdictions, which give judicial deference to the “intended parent” based on the contract terms, despite gestation by the surrogate that establishes her as a “natural” or “birth mother” under the Uniform Parentage Act (Calvert 1993; Reference Kindregan and McBrienKindregan and McBrien 2011). Johnson v. Calvert held that when the natural mother does not coincide in one woman, it is the “intended” parent who wins, regardless of feelings like remorse in the surrogate, which now extends regardless of genetic connection (Id.; In Re Marriage of Buzzanca CA 1998; see also Perry-Rogers v. Fasano NY 2000).

Currently, there is vast diversity among state laws on surrogacy, including total bans, prohibiting compensation, statutes that regulate the practice, and absence of any law (Reference Kindregan and McBrienKindregan and McBrien 2011). Surrogacy remains largely unregulated and falls outside the protection of federal adoption statutes.

Finally, surrogacy is a context normatively considered a bastion of passion: mothering. However, the linchpin of surrogacy is detachment from feeling “maternal,” that is, the ability to gestate then terminate parental rights against normative expectations. I offer an affective, relational portrait of contracting as it interfaces with developments in reproductive medicine amidst an unsettled terrain. I selected surrogacy as a case precisely because it highlights variables like emotion and legal uncertainty in a particularly overt way.

Considering Emotions in Exchange Relations

Although studies on disputing establish that feelings are present in all relationships to varying degrees, ample law and society literature on exchange relations has yet to address the role of emotions in contracting. Conversely, extensive sociological scholarship on emotion management fails to analyze the role of law. I unite these literatures by introducing the sociology of emotions into the study of exchange relations.

Risk, Uncertainty, and Exchange Relations

A rich literature in law and society rejects the liberal model of contracts to examine how parties derive, understand, and enforce the terms of their agreements. The contract-as-relation model, spearheaded by Stewart Macaulay, emphasizes that social, community, and business norms coupled with formal law help structure commercial dealings (Reference BernsteinBernstein 1992; Reference BlauBlau 1968; Reference EllicksonEllickson 1994; Reference GranovetterGranovetter 1985; Reference MacaulayMacaulay 1963; Reference SuchmanSuchman 2003). In general, contracts manage risk, serving as insurance for the parties in case of breach (Reference MacneilMacneil 1974). However, Macaulay revealed that businessmen often preferred informal agreements to formal contracts, and rarely invoked formal remedies when disputes arose, or nonperformance (1963). His work continues to encourage a study of contracts from the “bottom up” that gives maximum expression to relational business norms and values, as well as power (2000, 2005).

Contracts do not emerge in isolation, but within larger systems of social beliefs and power relations embedded in subculture (Reference SuchmanSuchman 2003). Therefore, Mark Suchman encourages scholars to take an “artifactualist” approach to contracts, being attentive to the “actual exchange relations that real people form or to the actual contracts that real people write” (Id., 95). Recent studies show the field continues to thrive (Reference Ayres and KlassAyres and Klass 2005; Reference EigenEigen 2008, 2012; Reference Plaut and Robert BartlettPlaut and Bartlett 2011), but do not examine its emotional dimensions, or the relationship between emotions and risk (Reference KahanKahan 2008). Further, how can “workaday norms” (Reference EllicksonEllickson 1994) and “reputational bonds” (Reference BernsteinBernstein 1992) be primary drivers in contracting contexts, like surrogacy, where law, relationships, and norms are far less developed?

I use the artifactualist approach to reveal the constitutive power of law and social norms (Reference YngvessonYngvesson 1988). My analysis of the exchanges and embedded relationships between parties to surrogacy fits well into “typical” business transactions but extends the current literature. While Macaulay's subjects in traditional business settings spent little time planning prior to entering contracts, he opined that more planning might occur when the gains of detailed contract terms outweigh the costs, or where it is likely significant problems will arise in the performance of longer term agreements (1963). Surrogacy contracts are carefully planned because the potential sanction—getting or not getting a child—makes formality an advantage; by definition contracts are intended to ensure predictability and security. Further, contract performance occurs over time, minimally, from in vitro fertilization through gestation, to birth.

What happens to “noncontractual relations” in business when, as in surrogacy, unsettled and conflicting laws make it a much more risky and less predictable enterprise, when social norms and business practices are not entrenched, and when ongoing business relationships are absent, the factor which motivates parties not to “welsh on a deal” (Id. 14)? While individuals may attempt to minimize risk, they cannot eliminate the possibility of harm, injury, or misfortune, at the core of vulnerability (Fineman 2008). As Martha Fineman explains, “understanding vulnerability begins with the realization that many such events are ultimately beyond human control” (Id., 9). Further, it is universal, which leads individuals to look to social institutions to lessen that vulnerability (Id., 10). Attorneys intervene as “facilitators” in business settings to absorb, suppress, and avert crucial uncertainties that might otherwise elevate transaction costs, risk, and discord (Reference Suchman and CahillSuchman and Cahill 1996). I will show that feelings cause parties to exert greater degrees of control in surrogacy relations.

Conflicting state policies on surrogacy exacerbates vulnerability and risk. As Margaret Brinig predicts, “uncertainty itself begets more litigation, higher prices to attempt to secure conformity with the contracts, and more opportunism on the part of all involved, particularly, intermediaries … to extract concessions ranging from restrictions on her behavior during the pregnancy to permission to film the delivery (2000: 71). My findings confirm these “restrictions on behavior,” visible in a variety of emerging contract provisions and practices currently embraced by lawyers, agencies, and counselors that use emotion management rules as a means of managing risk. But according to Brinig, once law is settled, the “apparent (and illusory) ‘insurance’ of a lawyer-drawn contract will disappear” (2000:76).

However, from a law and society perspective, the contract—which is relational, symbolic, and not merely instrumental—will likely not disappear. I embrace the model of contracts as exchange relations that have extra-legal dynamics, where actors deploy contracts as a technical means of structuring their relations, as symbolic representations, and as cultural displays that inhere particular normative principles and social experiences (Reference SuchmanSuchman 2003: 100). Surrogacy is a doubly relational contract: not just as between the promisor and promisee for services and consideration but also because the “product” is human (Reference RadinRadin 1987). It is distinguishable from discrete transactions, where a buyer demands packing material for fragile cargo to minimize risk. Surrogacy rules are not necessarily rational, but symbolically offer a risk management solution through formalized emotion management, given the legal ambiguity (Reference EdelmanEdelman 1992). However, the impressive body of work on exchange relations fails to address the role of emotions in how parties deal with the formation and performance of the agreement. I use the case of surrogacy to expand understandings about contracting behavior.

Emotions, Lawyers, and Disputing

While past empirical research in law and society has failed to couple the study of law with emotions in contracts, it has addressed them in the context of disputing, and recently, on security and crime (Reference PasquettiPasquetti 2013). Legal institutions have developed an array of techniques for containing feelings, regarding them as disruptive to the institutional discourse of rationality. Courts route “garbage cases” into mediation where orderly forms of talk train parties to suppress emotion in favor of settlement (Reference MerryMerry 1990). Divorce lawyers push clients to be dispassionate, depending instead on “unclouded” professional authority for sound guidance as to what is legally relevant (Sarat and Felstiner 1986). Lawyers construct the meaning of divorce by comparing their client's feelings to “normal” cases (Id.). Similarly, legal discourse reinforces male privilege and female dependency by deeming emotions during conflict as differently appropriate based on gender (Reference Conley and O'BarrConley and O'Barr 1998). Behavior considered “emotionally intense” which does not conform to social conceptions of masculinity during conflict is policed (Merry 2009). Relationship conflicts are acknowledged to be highly affective experiences (Reference GalanterGalanter 1983; Reference MaldonadoMaldonado 2008; Reference NaderNader 1990). In fact, theorists of law and emotions contemplate the use of law as a strategic tool to shape, channel, or mobilize emotions, but disagree on the merits of “therapeutic jurisprudence” (Sanger 2013:59; see also Reference Abrams and KerenAbrams and Keren 2007; Reference BandesBandes 1999; Reference MaroneyMaroney 2006; Reference NussbaumNussbaum 2001). Given the emotionality of disputes, I show contracts are structured to minimize conflicts by managing feelings.

Law, Emotion Management, and Feeling Rules

A rich literature on the sociology of emotions complements law and society, offering insight into how law shapes emotion. I embrace the definition of emotions used by sociologists, which focuses less on the individual processes that give rise to feelings as is the focus of psychology, but instead “places the person in a context and examines how social structure and culture influence the arousal and flow of emotions in individuals” (Reference Turner and StetsTurner and Stets 2005: 2). It subsumes terms like feelings, affect, and sentiments. Individuals learn the cultural “vocabulary” or labels, behaviors, responses, and shared social meanings for each emotion, associating them with distinct types of relationships (Reference Gordon, Rosenberg and TurnerGordon 1981). When there is discontinuity between expectations for a given situation and an outcome, negative emotions like fear, anger, and distress are aroused (Reference Turner and StetsTurner and Stets 2005: 290). Jealousy, commonly reported in surrogacy relations, signals “the intrusion of another into a valued relationship” (Id., 2). Certainly, many emotions are positive, like joy, gratitude, hope, and pride (Id., 289). A social constructionist view asserts that emotions are constituted within particular social norms, social relations, and institutional settings, including law, medicine, and religion (Reference Calhoun and BandesCalhoun 1999: 219).Footnote 3

I engage Arlie Hochschild's research on how feelings are constructed and managed by examining the phenomenon in the spotlight, and the shadow, of law (Reference HochschildHochschild 1979, 1983, 2003). In The Managed Heart, Hochschild defines a feeling as a “script … one of culture's most powerful tools for directing action” (2003: 56). She coined these scripts “feeling rules.” Sometimes the scripts direct action on behaviors, and often require “deep acting” and management, especially in the context of service work like that accomplished by flight attendants (Id.). Emotional labor is that which “requires one to induce or suppress feeling to sustain the outward countenance that produces the proper state of mind in others … [which] calls for coordination of mind and feeling” (1983: 7). To what extent are employees able to align their inner emotions and outward displays to perform emotional labor (Id.; Reference GoffmanGoffman 1959)? Once commercialized, emotion work is transmuted from a private to a public act where feelings are directed and supervised (Hochschild 1983: 118–119). Feeling rules are no longer matters of personal discretion but are spelled out as rules that govern behavior, and disseminated through discourse (Id.). Contracts can be a form of discourse through which lawyers draft feeling rules to govern client behavior.

How do particular agents, like lawyers, guide emotional socialization to create “emotion cultures” (Id.; Reference LoflandLofland 1985)? Cognitive strategies used to manage emotions focus on altering the meaning of a particular situation (Reference Thoits and KemperThoits 1990). When a person is unable to manage his or her emotions or displays as expected, the result is what Thoits called “emotional deviance” (181). A study by Pierce examined emotional labor in law firms, finding a gendered division between male and female litigators whose aggressive tactics are labeled brash, rather than effective (1995). Women lawyers and paralegals are expected to “mother,” reassure clients, and act deferentially to male colleagues (Id.: 86). Common emotion management strategies include seeking support and reinterpreting the situation (Reference Thoits and KemperThoits 1990). Individuals are socialized to perform the emotional labor of detachment—a critical aspect of surrogacy—by learning to shun earlier socialization in favor of “normalizing talk” and an attitude of disengagement for their careers, like medicine (Reference CahillCahill 1999; Reference Smith and KleinmanSmith and Kleinman 1989). I will show that reproductive lawyers, agencies, and counselors are motivated to minimize negative emotions that present risk and normalize detachment, creating new emotion cultures, ironically constructing displays of bonding between the surrogate mother and child as “emotionally deviant.”

Note that established strategies are used to manage the physical risks of pregnancy generally, including restrictions on lifestyle, diet, and activities, and especially in the context of adoption, emotional restrictions on contact between the birth mother and the newborn, like breastfeeding, handling, or even viewing the baby prior to separation. First, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) issues guidelines regarding diet, smoking, exercise, and other practices during pregnancy (ASRM 2013; ACOG 2002). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and ASRM recommend formalizing those risks for surrogacy, stating, “the parties to a Gestational Carrier agreement should discuss and memorialize all possible contingencies that can arise in the course of the relationship” (ASRM 2014: 38).

Second, managing not just physical risks, but risks of attachment in pregnant mothers, happen through legal practices, especially, separation and contact restrictions prior to adoption. Prohibitions on breastfeeding likely diffused from early practices in homes for unwed mothers but have not necessarily been codified in adoption statutes (Sollinger 1990). Maternity homes shifted from requiring pregnant women to “touch, nurse, and room with their infants” in the 1930s to discouraging “any contact at all” after the Second World War (Reference SangerSanger 1996: 445–447). In analyzing “maternal separation decisions,” Carol Sanger challenges the legal norm that abandonment is deviant and “selfish” (Id.). Recently, Sanger traced the trend away from “complete severance” between mother and child at birth toward postadoption visitation agreements, less enforced in involuntary termination cases, where future contact is denied (2012: 312). Criminal justice policies separate mothers from children during incarceration, prohibiting visitation, continuing ties, or encouraging permanent termination of parental rights under the Adoption and Safe Families Act (Reference FlavinFlavin 2009). In fact, critics of surrogacy emphasize the devaluation of the gestational mother's labor, as well as the use and control of pregnant bodies that varies by class, race, place, and lack of power (Reference Dasgupta and DasguptaDasgupta and Dasgupta 2014; Reference RobertsRoberts 1995, 2011). They object to the transposition of scripts, like detachment, onto surrogacy practices.

What happens when an emotion culture is legalized? While several scholars have pursued emotional management since Hochschild (Reference BarbaletBarbalet 2002; Reference Clay-Warner and RobinsonClay-Warner and Robinson 2008; Reference Collins, Scherer and EkmanCollins 1984; Reference Goodwin, Jasper and PollettaGoodwin, Jasper, and Polletta 2001; Reference KatzKatz 1999; Reference LivelyLively 2013; Reference McCreightMcCreight 2005; Reference WhartonWharton 2009), almost none address the role of law (Reference PiercePierce 1995). To extend this literature, I examine legal norms, practices, and conceptual schemes. I will show that law generally, and surrogacy contracting specifically, is a place wherein not only emotions are constituted but also as a result of their management, social norms surrounding motherhood, fatherhood, and family, especially in the absence of informed agreement on the ethics and legality of commercial pregnancy. I demonstrate how attorneys with the help of other specialists generate multiple “feeling rules” in surrogacy contracts to manage emotions of intended parents and surrogates, and explain why. After all, detachment is a central “rule of the game” in surrogacy, violation of which may lead to disputes, breach, and significant risk, especially where law is unsettled (Reference BurawoyBuroway 1979; Hochschild 1983).

Data Collection and Methodology

Surrogacy as a case was selected for study precisely because it highlights variables like emotion and the unsettled nature of law in a particularly overt way, present but unexamined in other types of exchange relations. However, surrogacy contracting was an unmapped socio-legal terrain. Thus, two primary research methods were used to collect and analyze data to determine how surrogacy contracting operates, how it is experienced, and both how and why feelings are managed through the process.

First, from March 2011 through April 2012, I conducted 115 in-depth, semistructured interviews in 20 states across the United States with four primary subject groups: (1) attorneys who draft surrogacy contracts, most of whom specialize in assisted reproductive technology or adoption law; (2) agencies that match surrogates together with infertile or otherwise interested singles and couples; (3) women who have been either gestational or traditional surrogates; and (4) intended parents who used a surrogate to gestate their baby. I conducted supplementary interviews with husbands of surrogate mothers, and with psychologists and counselors who were affiliated with matching agencies who participate in mental health screening, evaluation, and therapy for parties during the process. The interviews were designed to elicit how parties to surrogacy contracts manage feelings and relationships, either through formalized contract provisions or through informal practices between the parties as facilitated by their lawyers and matching agents. The interview sample is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Interview Subjects by Category N = 115

a While the total number of participants is 115, some of those individuals overlap into more than one category. For example, 10 lawyers of the 66 interviewed also overlap into other subject categories, such as being a parent through surrogacy. Since agencies are entities, and not individuals, there is no possible subject category overlap. There is, however, for matching agency representatives. Also, none of the husbands of surrogates overlapped into any other category.

Since the population of potential respondents was previously unknown, I used a snowball or “niche” sampling technique to identify respondents in states initially selected based on legality of surrogacy (Snow, Morrill, and Anderson 1993). Capturing the unsettled nature of this field, the 20 states in the sample vary along a spectrum of “surrogacy friendliness,” or whether the practice is legal in that jurisdiction, the law is ambiguous, prohibited, or simply absent.Footnote 4 Underscoring the legal ambiguity, there is variation even among surrogacy friendly states, for example, that surrogacy is legal for married heterosexual couples only, and by statute (Texas), or that only uncompensated surrogacy agreements are valid (Washington).

My sampling strategy assumed state law variation would be relevant to the research question posed herein. However, two significant findings are that: (1) legal prohibitions do not prevent the practice and (2) surrogacy contracting has become multijurisdictional. For example, intended parents who live in Washington, D.C. where commercial surrogacy is prohibited might hire a lawyer licensed in Massachusetts, whose Wisconsin matching agency found them a surrogate who lives in Illinois. Also, the internet has also made it easy to find gamete donors and surrogates for hire, despite locale, or legal restrictions. Parties, lawyers, and agencies that match parents with surrogates may, or may not, ever meet in person. Further, a growing number of international intended parents—who live in Europe, Asia, Australia, South America, or the Middle East where the practice is illegal—hire lawyers to help them create families from surrogacy friendly jurisdictions in the United States in the absence of informed social policy.

The snowball sample of subjects was primarily derived through referrals from within their social network, either by direct professional connections or by reputation, and by an “opt in” recruitment design. I used a nonprobability, purposive sampling technique that requires the researcher to seek out the relevant social settings, spatial or organizational “niches” that are most likely to uncover the range of actors to surrogacy contracts and the interactions between them (Babbie 2009: 192; Snow, Morrill, and Anderson 1993). It requires that one sample as widely as possible within the “venues,” sites or contexts until redundancy is reached (Luker 2008: 161; Id.). This method is appropriate where the researcher cannot construct a classic sampling frame, as in this case, where little is known about the underlying population parameters. Instead, I mapped out the contexts and places where these exchange relations are initiated and performed, which could be anywhere within the United States (Luker 2008).

Of the 20 states in my sample, 14 were visited in person; once I returned from an in-person visit to a particular field site, I received e-mails and/or phone calls from subjects in other states interested in “opting in” to the study on hearing of it from a colleague, friend, or their lawyer. I gained far more access then I originally anticipated, and eventually had to turn away willing participants. The interviews were audio recorded with the consent of the participant and average nearly 2 hours in length. The digitally recorded interviews were professionally transcribed and anonymized to insure confidentiality and privacy for the participants in the study. Pseudonyms were generated for each individual participant as well as each matching agency. The interview data were then qualitatively analyzed using grounded theory coding to develop categories for interpretation (Reference CharmazCharmaz 2006; Luker 2008; Reference Snow, Morrill and AndersonSnow, Morrill, and Anderson 2003).

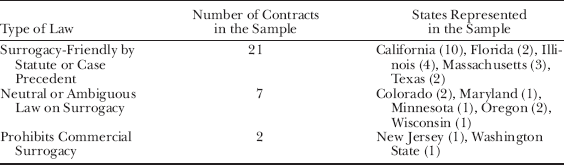

I also conducted an exploratory content analysis on a sample of 30 surrogacy contracts from 11 jurisdictions to analyze both the nature of terms and provisions in the agreement, and the mechanism whereby specific terms, rules, and provisions seek to manage emotions. The contract sample is detailed in Table 2. The size of the sample was limited by lawyers' reluctance to share contracts they reportedly spend endless hours drafting, withhold from competitors, and a fear of liability should “their” contract be used without permission in a locale where the provisions are unenforceable or illegal. Given these conditions, the sample size is ample.

Table 2. Sample of Surrogacy Contracts N = 30

I sought to detect patterns in the types of terms, rules, and provisions developed and used by lawyers and matching agency representatives to manage emotions and otherwise govern the relationship between the surrogate and intended parents, and the degree to which language across contracts varies. Each contract in my sample was methodically content coded using Atlas.ti computer-aided qualitative data analysis software (Reference FrieseFriese 2012; Reference SaldanaSaldana 2009; Reference Snow, Morrill and AndersonSnow, Morrill, and Anderson 2003). I searched the text of contracts for coherent meaning structures, and identified core consistencies and patterns in the data (Reference PattonPatton 2002).

The combination of these two methods enabled the collection of data to reveal why and how lawyers use feeling rules in contracts to manage the emotional aspects of the surrogacy agreement according to the drafters and parties, and the consequences thereof.

Findings: Feeling Rules and Practices

Like all contracts, rules in surrogacy represent efforts to anticipate the “worst case scenario” to avoid risk (Lawyer CA). “Everybody thinks surrogacy is simple until we go through the 37-page contract,” evidencing a Wisconsin lawyer's effort to “disaster plan.” A colleague in Pennsylvania who caters to gay and lesbian family formation explains that state has “sort of a no man's land of law.” Thus, the lawyer's job is to “try to help people from their family however they want as long as they … know the risks,” (Lawyer PA). In Maryland, an attorney describes with concern “Russian roulette states where on its face, the statute says it's prohibited by law, and lawyers do it anyway … this is like somebody's child!” Given the consequences, the attorney was determined to research “all the cases that make it to the news like what horrible thing can happen.” What s/he later called the “parade of horribles” became formalized rules in the contracts which, “tend to be long—attorneys on the other side whine about it” (Lawyer MD). Even in surrogacy-friendly California, a lawyer confesses working hard to “explain the risks” and draft a “thorough” contract because surrogacy practice is still “scary.”

But lawyers' efforts go far beyond anticipating potential conflicts for risk management. Where the law is uncertain and the stakes are high, risk management goes hand in hand with emotion management. I find that the web of formal restrictions in contracts, along with informal practices like “triage,” are developed and deployed by lawyers in collaboration with matching agencies to prevent emotional attachment, resentment, or alienation in the surrogate mother and handle feelings like vulnerability, anxiety, and jealousy in the intended parents. Legal actors also work to intentionally cultivate particular emotions like gratitude and excitement. Even when not realistically enforceable, these rules are still influential, symbolic, and institutionalizing: formal contract provisions are used, shared, and adopted in the field.

I will detail three main categories of rules and restrictions created, deployed, and enforced by lawyers and agencies to mange feelings. They include: (1) lifestyle rules and behavioral restrictions; (2) rules governing breastfeeding, an “intimate” form of contact with the baby; and (3) rules governing viewing, handling, and future relationships with the newborn. Construction and intervention surrounding these rules are intended to promote feelings of attachment in the intended parents, and conversely, encourage detachment in the surrogate with an eye toward smooth performance of the contract. Rules are coupled with informal emotion management strategies that I call triage, an intervention to minimize conflicts and risk.

The predominant emotions reported by subject participants include the following: abandonment, alienation, anger, anxiety, excitement, fear, gratitude, jealousy, joy, resentment, vulnerability, and “womb envy.” They are depicted in Table 3 by subject, and discussed throughout the analysis, below.

Table 3. Types of Emotions Managed in Surrogacy

Lifestyle Rules and Restrictions

Across jurisdictions, lawyers reported the need to not only ensure the emotional stability of the surrogate, but also to regularly manage the intended parents' anxiety and control. When drafting surrogacy contracts, lawyers insert extensive lists of rules the surrogate must follow based on past agreements, and particular demands of the intended parents. Intended parents have ample power since they pay for the transaction. Contract rules may include the degree of an intended parents' surveillance over the surrogate, restrictions on the surrogate's daily activities, or requiring the surrogate to consume solely organic foods and supplements while prohibiting caffeine, sugar, or fast food throughout the pregnancy. Some rules require that the surrogate engage in a particular activity—like acupuncture or going to the gym—or prohibit her from doing so—such as bans on microwaves, hairspray, manicures, or changing cat litter. Table 4 lists the kinds of rules and restrictions on behavior coded in the content analysis of surrogacy contracts.

Table 4. List of 127 Lifestyle Rules and Restrictions

The following is a list of codes for lifestyle practices, habits, activities, or household items that are specifically restricted, encouraged or otherwise regulated within the surrogacy contract. SUR H is a rule that applies to the surrogate's husband.

The interview data highlight the ways in which contract provisions serve as a tool for feeling management, and in many cases, too hard to police to be anything but symbolic. Lifestyle rules and restrictions on behaviors are a key strategy deployed by lawyers on behalf of distraught, anxious, and demanding intended parents. According to interviewees, feelings like fear, anger, and vulnerability in the intended parent(s) cause them to not only assert greater degrees of control over the carrier but also with the help of lawyers, also cultivate attachment in the baby they do not carry themselves.

A Minnesota lawyer identifies feelings of sadness, worry, and anxiety in surrogacy cases, noting that it makes for “very demanding” clients. S/he also reveals a spectrum of control:

I've had parents who sent groceries on a weekly basis to their carriers to make sure they were eating healthily. I've had parents that just never asked a question about what the surrogate was doing. So it runs the gamut from total obsession to total laissez-faire, and it's strictly a personality issue. But it's a very tricky thing. You have a pregnancy that is the surrogate's body and her pregnancy and the parents' child and that child's pregnancy, and they coexist at this nexus point of the surrogate's womb, and both parties have an interest in what's going on in there. And the parents really have no meaningful control other than contractually, which is questionably enforceable. (Lawyer MN)

A California lawyer agrees the nexus point in contracting is the womb, noting, “you're dropping fairly controlling and accomplished people in an area where, by definition, they have no control.” Thus, the demanding client tends to control the surrogate with rules because they feel vulnerable, according to their lawyers. For a Pennsylvania practitioner:

I think with intended parents, there's certainly a vulnerability and a need to control that comes out because they're – someone else is basically physically carrying, literally, their child and is away from them. And that is a vulnerable situation to be in. And I think that's where crazy fish restrictions come in. That's sort of their – an expression of their need to control the situation. But the reality is you're never going to be able to control this person's every move. (Lawyer PA)

The “crazy fish restrictions” refers to the list of prohibited foods in contracts that are getting ever more detailed. But not all professionals in the industry comply. As one lawyer asserted, “You have to be reasonable … to put a complete ban on nail polish and the hair dye—most doctors will tell you now it's okay to get your hair highlighted” (Lawyer CA). While “hates to be harsh,” this lawyer resists demands for those rules by soliciting empathy in intended mothers, persuading, “in a perfect world [if she] could get pregnant, she would probably realize that at seven and a half months pregnant, the greatest thing ever would be to lay in a chair and get a pedicure” (Id.). Still, some of those rules are inserted not by clients, but by other lawyers.

The most extreme examples include parents who, reportedly driven by lack of control over the physical pregnancy, request that their surrogates move in for 24-7 monitoring. While agreeing to an organic food diet, yoga classes, and daily texts, a Wisconsin surrogate drew the line at in-home surveillance, asking her lawyer to step in to manage the parents' expectations. Similarly, a California lawyer explained that “it is not unusual” for clients to request “nanny cams” for “more access” to police the rules. However, s/he refuses to put surveillance in the formal contract, advising clients “that's way over the line.” One agency owner in Florida reported searching for a surrogate willing to live with the intended parents and follow a vegan diet, even though she believed the request was “unreasonable,” not unlike a New York lawyer who described clients as “intrusive and overbearing.” Breaches are reported to lawyers who are expected to enforce the terms of the agreement, who respond by diffusing conflicts on their own through triage, or enlisting the support of agency counselors.

A Texas lawyer depicts surrogacy as an “emotional roller coaster,” particularly when infertility plays a role, because “there's even a more heightened sense of fearfulness and anticipation that something's going to go wrong,” either medically or legally. While the experience can be fraught with terror, fear, and uncertainty, it can also be “an adventure, a journey” (Id.). Others add envy to the mix, especially for intended mothers. As one lawyer puts it:

There's also then the jealousy component about the fact that the surrogate can carry the baby and she can't. It's called womb envy … And so some of the carriers would rather work with a gay couple because they have no baggage; they have no womb envy. (Lawyer MD).

Since she was “scared that women can be jealous,” a California surrogate preferred to carry for two “very sincere gay guys,” even though “one was HIV positive” which to her was “less of a big deal” than a jealous intended mother. If jealousy signals the “intrusion of another into a valued relationship” (Reference Turner and StetsTurner and Stets 2005: 2), womb envy occurs when the surrogate “intrudes” into the once hoped-for valued relationship between baby and intended mother.

These subjects are not alone in considering how envy and jealousy influences demands for control through lifestyle rules. A California lawyer states candidly:

Some of the smoothest cases I've had have been involving my same-sex couples, especially gay men. They come into surrogacy knowing exactly what their issue is and why they need a surrogate … I've seen it many times where the surrogate becomes pregnant, and all of the guilt and all of the inadequate feelings that the intended mother has struggled with come to the forefront. There's then a resentment against the surrogate. (Lawyer CA)

Lawyers are motivated to avoid risk and keep cases running smoothly, explaining the preference for same-sex clients to avoid womb envy. Another lawyer concurred, “it's certainly no secret that a gay couple … need to bring someone else into the process to have a family. There's no shame about that” (Lawyer PA). A surrogate from Illinois justified her preference in carrying for a gay couple, explaining, “They're so easygoing, and they're not as—I don't know how to explain—how some intended mothers can be—bitter, jealous.”

And yet, the legal risks for homosexual clients are much greater, since even some surrogacy-friendly jurisdictions by statute limit benefits to married, heterosexual couples.Footnote 5 Further, same-sex adoption and marriage are not universally recognized (Goldberg et al. 2014; Reference Hollinger, Heifetz and CahnHollinger and Cahn 2004; Reference SavageSavage 2014). Clearly, when lawyers are committed to serving anyone that wants to form a family, the value of emotion management outweighs a simple “risk management” calculation.

Dashed hope, “womb envy,” and vulnerability are not the only motivators for control through rules. Wealth and power also play a role, not to mention individual personalities and life experiences. Other subjects dispelled the “easygoing gay dads” stereotype. While it is true that gay intended fathers do not have to manage disappointment over infertility, never having expected to carry, they can still be demanding of their surrogates. Control and power is evidenced through their policing of lifestyle rules and restrictions. As a lawyer who has served a large number of “wealthy” gay clients recalls:

It was just like needing the check-ins, having to be available 24-7. If she didn't return a phone call within an hour, he freaked out, where thank God his partner is even-steven. Towards the last trimester when she was so at her wit's end, it was like, ‘He'll take over. You don't have to deal with him anymore.' Just wanting to know every little detail – just the whole thing. And he's also one of those where he's very wealthy, so it's kind of like, ‘I'll just pay you more money if you shut up about it.' And it's like okay, at a certain point, that doesn't work anymore. (Lawyer CA)

Just as this lawyer drew a line on this client's demands on the surrogate, and for her benefit switched to the more “even” partner, others use emotion management and honesty when intended parents exert too much control. In this case, triage included managing the demands of the intended parents to ensure the surrogate's emotions—whether anger, hurt, or resentment—do not cause the relationship to unfurl, given the stakes.

No matter the intended parents' sexual orientation, this “micromanagerial” approach can backfire. I heard several reports of overly managed surrogates who, when offended, cut off communication with the intended parents as a push back form of control (Surrogate FL; Surrogate TX; Lawyer CA; Lawyer CA). They, after all, carry the baby, and thus hold many proverbial cards—arguably, the deck. Then, lawyers have to intervene after a conflict erupts to do “damage control,” as one attorney from Massachusetts described the triage. That lawyer fielded a call from a cut-off intended parent who frantically demanded, “We need a prebirth order immediately because our carrier's not talking to us and not letting us go to doctor's appointments anymore!” Even an intended parent from California, who matched independently with a surrogate online to avoid the cost of agency fees, admitted, “it got to the point where she just stopped responding to us because we were in her face too much and asking her to do crazy things.” This is one reason experienced reproductive lawyers continue to argue against on-line matching, downloading of contracts online, and entering agreements without legal representation. Their role as emotion managers—and effectiveness at it—can make, or break, a surrogacy relationship.

Some surrogates resort to self-help, such as venting online, while others call on their lawyers or agencies for intervention (Surrogate TX). In turn, lawyers and counselors provide emotion management strategies like triage as a push back against the demands of their clients, to diffuse tensions. According to one agency counselor, “I really encourage the intended parents to keep it as basic as possible because the surrogates don't want to feel micromanaged. They want to feel as if they trust them, and I encourage intended parents to remember that you have complete control over who you choose to be your gestational carrier, but once she's pregnant, you have to let go of some of that control” (Agency CO). Thus, lawyers and agencies try to cultivate trust in the intended parent(s), encouraging them to release some control. Addressing their fears and desire for control is achieved through emotion management, with an eye toward smoother relations, given risks and unsettled law.

Contact Rules and “Intimacy Restrictions”

Aside from lifestyle, I have identified a number of other feeling rules, a cluster of which I have coined intimacy restrictions. These are provisions that limit physical contact between the surrogate and a number of “others”—either her spouse/partner, the baby, or the parents themselves. Touching, nursing, and having contact with infants are intimacy practices to create an emotional bond between mother and child (Reference SangerSanger 1996). There are many examples of intimacy restrictions throughout the interviews, mirrored in the content analysis of contracts. In this article, I use examples of (1) breastfeeding provisions and (2) rules surrounding viewing, handling, and future contact with the newborn to demonstrate the ways in which intended parents, through their lawyers, exerts degrees of control as a way to manage their own anxiety that the surrogate might bond with the baby. Contact restrictions deployed in contracting alleviate fear and vulnerability in the intended parents that the surrogate will refuse to relinquish the baby, the crux of the contract. Formalized rules are presumed, conversely, to prevent bonding and emotional attachment in the surrogate. Lawyers establish feeling rules to contain clients' emotions as part of a larger strategy to contain risk. The contract itself anticipates potential emotional traps, but informal practices like triage lead an attorney, agency, or counselor to intervene when called on to diminish risk.

Breastfeeding Provisions

The unsettled, affective, and consequential nature of surrogacy practice also allows for the institutionalization of rules for breastfeeding, a unique form of intimate contact. Rules against nursing are intended to avoid the potential for more emotional bonding between the surrogate and the newborn, especially since the surrogate's body is technically no longer needed to sustain the baby's life. Prohibitions on breastfeeding likely carried over from early practices in homes for unwed mothers but have not necessarily been codified in adoption statutes (Reference SangerSanger 1996; Reference SolingerSolinger 1990). For example, consider the following contract provisions:

Carrier acknowledges the importance of immediate bonding between the Child(ren) and the Commissioning Couple and agrees to assist in every way possible to strengthen that bonding including but not limited to Carrier agreeing not to breast feed the Child. (Contract, FL)

The Traditional Surrogate further agrees that because she is entering into this Agreement with the intention of providing a service to the Genetic Father and Intended Father, it is in the best interests of the Child … [t]he Traditional Surrogate will not nurse the Child. (Contract NJ)

CARRIER represents that she will not form nor attempt to form a parent-child relationship with any CHILD she bears pursuant to the provisions of this Agreement. All parties understand that under no circumstances may CARRIER ever breast feed CHILD. (Contract MA)

These contracts from diverse jurisdictions emphasize that prohibitions on breastfeeding are intended to limit emotional bonding or prevent the surrogate from forming a “parent-child” relationship. These are feeling rules intended to discourage emotional attachment between surrogate and child; birth mothers are normatively expected to bond through nursing.

However, agreements vary, mostly depending on the nature of the relationship that has developed between the surrogate and her intended parent(s). Thus, contrasting examples of contract provisions actually encourage nursing or pumping:

The parties recognize the benefits to the Child associated with the availability of breast milk. Carrier will use her best efforts to express breast milk after the Child is born and to provide such breast milk to Parents. Carrier, alone, will determine what is a reasonable amount of breast milk and a reasonable time frame for providing it. (Contract WI)

For a reasonable time after delivery, to pump and deliver breast milk to Genetic Parents, with Genetic Parents' concurrence, at Gestational Carrier's sole discretion and Genetic Parents' sole expense, for the purpose of feeding the newborn Child. (Contract MN)

It is not uncommon for parents to request the pumping of breast milk for an agreed-upon period of time, with contracts delineating fees as payment for “service” and “inconvenience,” and reimbursements for shipping costs. Consider the following representative provisions:

In the event the Surrogate agrees and Intended Parents request for Surrogate to pump breast milk after the birth, Intended Parents shall pay for all costs associated with the pumping, to include but not limited to the cost of the rental of a breast pump, shipping costs, breast pads, supplies and breast feeding bras. In addition, the Surrogate shall be entitled to an additional allowance of $100.00 per week for up to six weeks after the birth. (Contract CA)

The parties have agreed that the Gestational Carrier will pump breast milk if requested by the Intended Parents. In such event, Carrier will be reimbursed $400.00 per week plus the cost of supplies purchased by Carrier. (Contract CO)

Fees for the provision of breast milk vary, as these do, from $100–$400 per week.

Contracts can also include provisions regarding when breast milk will be provided. Some surrogates agree to nurse or pump order to deliver colostrum to the baby only following delivery, or for some specified period of time. However, the interviews revealed that informal arrangements are often made as the emotional dynamics of the relationship unfold over the course of the pregnancy. Opining, “it's a highly personal decision,” a Texas lawyer's experience is that the parties formalize in the contract that the parents will “pay the cost for pumping” breast milk, but informally has also seen breastfeeding postdelivery in the hospital. Sometimes informal agreements to nurse, despite the contract terms, causes angst in their lawyers, who work hard to employ emotion management for risk management. A Massachusetts lawyer vented:

My attitude is that when the women have the baby, from the beginning, they say this is their baby. If you allow them to breastfeed, then you're going to connect. You're going to start that bond with her and the baby. It's going to be so much harder for her, and it's not fair to her. So if you want breast milk, have her pump, have her ship. That's a non-issue; just don't have her breastfeed.

This lawyer believes breastfeeding yields connection with the baby, risking the goal of the contract: establishment of legal parentage. While lawyers try to prevent physical bonding by delineating pumping in the formal agreement, parties behave as they like. Surrogacy contracting is thus a quintessential “exchange relationship” (Reference MacaulayMacaulay 1963, 2000). Parents manage the tension between their anxiety over bonding, legal risk, and their desire to provide nutrition to the baby for optimal health.

Whether such emotion management is justified is less clear; according to a lawyer from Virginia, “some carriers are able to breastfeed and stay disattached.” In fact, several convey cooperative and friendly arrangements where jealousy, anxiety, and control fall away, or never existed. Lawyers and agencies were eager to report that surrogates and parents often have a mutually supportive and endearing relationship, “working together for team baby” (Agency Counselor CO). An agency owner and surrogate in Oregon described her experience:

Molly: So they took him and they dried him off, and [the father and mother] went over and “ooh'd and ah'd” over him, and they had their time. And after a little bit of time, they brought him over to me and let me hold him and I actually nursed him for –

Hillary: Breastfed?

Molly: I breastfed, um huh, because I had told them I would send them breast milk, so I nursed him in the hospital –

Hillary: Oh, okay.

Molly: – with [the mother] by my side. I wanted him to get her smell and her scent as he was nursing just so he knew that this was Mommy. So she sat by me while I nursed him, and then I would give him right over to her to snuggle and burp and all that so that they could do their bonding thing. She stayed in my room with me the whole time I was in the hospital. And then they left. And that was probably one of the hardest things, too.

Rather than believing nursing would create a bond between her and the baby, as an agency owner, Molly consciously joined the infant's new mother into the experience so they could bond. Clearly, Molly was willing to play for “team baby.” At the same time, she managed her inward feelings to accomplish the job at hand, admitting that saying goodbye to the family “was probably one of the hardest things, too” (Id.). There is no doubt that conflicting emotions abound even in successful legal arrangements. Perhaps in this case, integrating mom and dad into the mix minimized the legal risks.

According to lawyers, rules against breastfeeding are intended to prevent attachment, and manage the ultimate intention of the contract: to establish parentage. Otherwise, a Texas lawyer notes, “the intended mothers feel that that would be creating a parent-child relationship,” or as an Illinois surrogate admitted, “would take away from her bonding with the babies.” One Wisconsin lawyer with prior experience in adoption will not agree to “put that in a contract.” Laying out the reasoning:

I think there's a risk. That's even a more intimate act – I know that sounds surprising, but it really is. The child is born at that point, the child – that is a mother-child act that is really designed for bonding and attachment. And maybe that's my bent from adoption, but any birth mom who decides to breastfeed – she's keeping that child. (Lawyer WI)

Even though s/he knows “carriers who've agreed to do it only because they know how good it is for the child,” as a legal risk manager tells them, “You don't want it; it's not worth it” (Id)

Surrogates who have successfully provided breast milk and handed over the baby to its new parents would disagree. There are two sides to that coin; surrogates as well as lawyers engage in emotion and risk management. In another case, it was a surrogate who refused to nurse, asserting, “I do not want to breastfeed someone else's kid” (Surrogate FL). Intimacy restrictions, especially those related to breastfeeding, are efforts to manage the emotions of their clients as lawyers to tackle the uncertainty of the reproductive law field.

In fact, a key emotion management strategy used by lawyers to counter the intended parent's fear of bonding, or jealousy, is to encourage intended mothers to induce breast milk to nurse the baby. In other words, lawyers simultaneously try to prevent emotional bonding between the surrogate and the newborn, while actively cultivating it between the newborn and its new parents. According to one attorney, “There is a lot of evidence to show that there is a considerable amount of emotional bonding that occurs during breastfeeding. So intended parents want to do that, and there are devices now that you can have a fake breast and do it” (Lawyer CA). In one representative example, a California surrogate for twins described that her intended mother, “induced lactation and nursed the babies in the hospital … I think it was probably 8 to 12 weeks before the babies were born to try and help stimulate the hormones in her body to produce milk.” She also admitted that not nursing made it easier to “detach” and solidified her role as “the babysitter” by reminding her “these are their children.” Similarly, a Texas lawyer reported intended mothers are “able to breastfeed even though they didn't carry the child.” Cultivating the bond between a baby gestated by a third party and its new parents is not only a way to establish intent to parent for legal purposes, but an emotion management strategy.

Since breast-feeding is a quintessential symbol of maternity, rules against nursing not only manage bonding on the individual level but more broadly also disconnect a surrogate from her social identity as a mother. In fact, “appropriate” emotional expression for a surrogate is both policed and performed, especially during delivery. One traditional surrogate from Illinois painfully recalled how hard it was not to express her true feelings on the birth of her baby. Full of tears, she described the day after delivery in the hospital:

And then as each hour went by that day, I felt myself breaking down emotionally. And one of my best friends was there with me, but she didn't know that I was his birth mom. She's thinking I'm just the carrier. So it was really hard to explain how I was feeling because I couldn't tell her. But she was there, and she wouldn't leave. You know she thought that she was doing the right thing by staying there with me because my husband had to leave and go home to get our kids, but I just wanted her to leave so bad so I could just break down. (Surrogate IL)

This surrogate was compelled to perform what she believed was the appropriate way a surrogate is supposed to feel when completing delivery: emotional detachment. She was afraid to express her real feelings—“sadness” and “guilt”—because she was supposed to be “just the carrier.” She was coached that appropriate role performance—showing the emotion of a birth mother struggling with the experience—would violate newly encoded norms about what surrogates are supposed to feel, reinforced by contract.

The inverse is also true. Intended parents—especially intended mothers—who do not perform their new roles in socially expected ways are policed into doing so. This is particularly so if she does not demonstrate emotions normatively associated with motherhood. In response, attorneys encourage clients to start connecting with the idea of parenthood early on, even if they do not induce lactation. A fundamental strategy used to cultivate feelings in a parent is to advise them to play an active role in doctor's appointments, especially ultrasounds. A conflicted intended mother from California confessed that attending appointments and seeing the fetus, as her lawyer's triage directed, helped her to connect with the “idea” of motherhood, though she refused to induce lactation.

Rules on Viewing, Handling, or Continuing Contact

Another intimacy restriction used to manage attachment is the practice of preventing the surrogate from holding or even viewing the newborn following delivery, which extends into future contact with the family. The same rationale that applies to breastfeeding—rules to minimize legal risk by inhibiting emotional bonding—applies here. Feeling rules related to degrees of contact are attempts by lawyers, in the face of uncertainty, to channel their clients toward the ultimate goal of establishing parentage. Educated by a psychologist who specializes in adoption, a Minnesota lawyer believed it crucial to “break that bond.” The lawyer elaborates, “I think all the more reason why you want to take precautions to know that the carrier that you're dealing with can follow through and do what she has committed to do” (Lawyer MN). Since bonding and future relationships could interfere that “follow through” in a multijurisdictional legal environment, lawyers heed therapeutic advice.

Contracts can contain intentions and expectations for the delivery process or a “hospital plan.” A representative provision from a Colorado contract provides the following rules:

Upon delivery of the Child, the Child shall be placed with the Intended Parents so that they can hold and care for the Child. Intended Parents shall be exclusively entitled to feed, change and take care of the Child. Gestational Carrier will be permitted to contact and view the Child as solely determined by Intended Parents.

A Texas surrogate who carried triplets for a couple that viewed the relationship as more “transactional” describes the lived experience of this type of provision. She explained:

So they were all crying, and they pulled out each baby, and then they got to go hold them. The parents walked with the babies to the NICU, and the first time I held them was – they were a week, two weeks old … They immediately held them, and they got to hold them in their arms, walk out to show them to all of their family that was overflowing the waiting room, and then take them to the NICU … I would have liked to have held them at the very beginning. I think that would have been a nice closure, but I didn't get that. Nobody offered it to me, and it just went on.

While she did get to see the triplets a week or two following delivery, she did not see them again; the intended parents cut off contact with her. This was particularly upsetting for the surrogate, since she had serious complications following pregnancy, nearly bled to death, and lost her uterus as a result. Not only was she not compensated for the medical expenses, pain, and permanent loss—they did not visit her either in the hospital, or during her 6 months of bed rest.

However, there are differences in the degree to which intended parents monitor the surrogate's contact with the baby following delivery, or how much she wants. A Wisconsin surrogate who delivered in California shared her own birth experience. Although she did not get to hold the infant following the delivery, the new mother brought him into her hospital room later. With pride, the surrogate recalled:

When she came back into the room with the baby and showed him to me and I held him, it was like I was congratulating her on having a baby. And of course, I just gave birth to him. And usually, I guess, the congratulations should come to me. And it was just kind of funny how you do that. It was nice to do it, though. It was awesome to say like, “Congratulations on your family,” but I'm the one laying in the hospital. So it was just funny.

In this case, the parents asked her to do their second surrogacy, guaranteeing their continuing contact. A lawyer from Wisconsin describes the spectrum of contact in her practice from “dispassionate” after delivery, to playing an “aunt-type or godparent-type role.”

The image of the jealous intended mother was dispelled by more than one interview. Subjects reported their positive “birth stories” (Parent WA), like crying with joy, taking group photographs with the intended parents and the newborn, and having “alone time” with the baby and her own children before discharge from the hospital for “closure” (Surrogate IL; Surrogate FL; Parents IL; Agency OR; Agency WI). A Texas lawyer explained that giving the surrogate and her family the opportunity for “alone time” and “closure” was recommended by social workers. Lawyers rely on counseling professionals to avoid hurt feelings or remorse to achieve full performance of the agreement.

Still, the entire process requires inner feeling management, the outward performance of which might crack after delivery. While still glad she did it, an Illinois surrogate admitted:

I didn't realize this until after I had him, but during the pregnancy, I totally put up a wall. I did not let myself bond with him whatsoever. I didn't get excited about the things that I would have with my own. I – even though there's a baby growing inside of me, I never thought of him as my own or like mine – a part of me. I think I was just blocking – subconsciously blocking that whole connection, and I felt guilty somewhat, throughout the pregnancy, for not really caring about him like I should have or like I would have my own. But I think subconsciously, I was doing that, and it didn't hit me until after I had him at the hospital. It totally hit me like a ton of bricks.

Contact rules and intimacy restrictions with the newborn following birth are intended to protect against precisely this type of situation where the feelings do not “hit” until after the delivery. Lawyers try to minimize the risk by managing chances for attachment, especially after the surrogate's uterus has completed its task by giving birth. Ironically, a California lawyer pointed out that “only one time has the surrogate changed her mind, although I've had intended parents change their mind …at least 10 times.” If most surrogates follow through with the contract, it shows they succeed at their “emotion work” (Hochschild 1983).

This relates to the degree to which the surrogate will have an ongoing relationship with the parents—or the baby—after the contract has terminated. The content analysis reveals that contracts overwhelmingly provide intended parents exclusive rights to determine future contact, with the default proscribing any continuing relationship, exemplified by this contact provision:

[I]n the absence of any written agreement to the contrary, and in the best interest of the child, neither [the surrogate or surrogate's husband] will seek to view, contact, communicate with, or form a relationship with the child at any time following the child's birth, except with the prior consent of [Intended Parent] unless such a relationship is desired by the child at a later date when the child is at least 18 years of age and is able to make an informed decision to form such a relationship. (Contract, OR)

As soon as parentage is legally established, they are entitled to withhold contact from the surrogate. At that point, the exchange relationship is officially over, as is the opportunity for emotion management. Per an upset Florida surrogate, “they don't want to talk to the surrogate—it's a business agreement. They just want them to carry the baby, have the baby, and be gone.” Thus, agency representatives and lawyers commonly manage their clients' fear of being “ditched” or “dropped”. A surrogate from Illinois revealed “a fear that they would ditch me once they got their baby and that was a fear that I'd had from the get-go, once we got close.” A California lawyer has experienced “postpartum depression” in her surrogates, “because usually, the intended mother is sort of controlling and yucky” following birth, wishing “she could just make the surrogate go away.” When drafting the agreement, a New York lawyer believes the “biggest issue is, I would say, future contact.” Her role is to make sure “everybody's on the same page” to avoid any hurt feelings that could lead to conflicts.

Therefore, many lawyers and matching agents actively encourage their intended parent clients to express particular, positive emotions toward the surrogate, like awe, gratitude, and reassurance. Experienced practitioners warn against “abandonment,” which leads to feelings of loss, anger, and alienation described by the surrogates above. Even when the parents do not want the carrier to see the baby postbirth, some lawyers push them to allow it, also encouraging photos and a few e-mails during the postpartum period (Lawyer MA). Why? A Texas lawyer had to perform triage after a resentful and hurt surrogate who carried for a single intended father threatened, “She may not sign her relinquishment document!” The surrogate felt “very unappreciated” and “was really panicked about the fact she wasn't going to have an opportunity to say goodbye” when the father wanted the baby discharged on the day of delivery. Although as a legal matter the new father was free to cut ties with his surrogate, doing so could be risky.

Thus, informal triage strategies developed by lawyers to cultivate gratitude include persuading the parents send her gifts, spa packages, birthday wishes to the surrogate's own children, treat them to meals in restaurants, and more. Each of these makes her feel “appreciated” rather than resentful, used, or alienated, according to lawyers and agencies. That her parents said “Thank you, thank you for my babies!” made an Illinois surrogate's delivery “probably one of the best days of my life!”

Finally, some parents even keep the surrogacy confidential from the children born of it via a contract clause, making an ongoing relationship impossible. In those cases, “When it's done, it's done” (Lawyer TX). That is why counselors encourage lawyers “at the very beginning help them to understand that they may or may not talk to this couple again after the delivery” (Counselor CO). Thus, one primary difference between commercial surrogacy and the kinds of “noncontractual relations in business” studied by Macaulay and others, is that ongoing relationships are not contemplated by the formal agreement as a strategy for legal risk management. If ongoing contact occurs, it will only be after the exchange relationship—performance of the surrogacy contract—has legally ended, removing the risk.

Conclusion: The Legalization of Emotion

The end goal in surrogacy—as in all exchange relationships—is to avoid disputes and ensure smooth performance of the contract. My research demonstrates that feelings are a critical component of that relation. While mapping a new sociolegal environment, I aimed to capture through the case of surrogacy how deep legal institutions delve, and help constitute, our emotional lives. As Toni Massaro puts it, “norm policing is both an inside and an outside job” (1999: 81). Given the undecided policy terrain for commercial pregnancy, normalizing, and formalizing emotion management has significant social consequences beyond the individual.

My primary finding is that where the law is uncertain and the stakes are high, risk management goes hand in hand with emotion management, a phenomenon I introduce as the legalization of emotion. Attorneys and agencies that match surrogates with intended parents develop a web of formal rules and practices like triage meant to anticipate and manage feelings well beyond basic contract terms. When faced with feelings like resentment, anxiety, fear, “womb envy,” and more, lawyers and agencies work to manage feelings, directing “scripts” to keep conflicts at bay. These include cultivation of positive emotions, such as gratitude and excitement, especially in intended parents, encouraging them to cheer on a surrogate playing for “team baby.” Formally, feeling rules in surrogacy govern lifestyle habits and behaviors, like restrictions on diet and surveillance, as well as forms of intimate contact, like breastfeeding, viewing and handling the newborn, and future relationships. This web of rules “legalizes” and infuses emotion management into the exchange relationship. Construction and intervention surrounding each of these rules and intimacy restrictions is intended to promote attachment in the intended parents, and conversely encourage detachment in the surrogate. After all, the linchpin of surrogacy is establishment of legal parentage in the nongestational parent(s). Emotions, coupled with real medical dangers and unsettled reproductive policy, exacerbate this risk.

However, feeling rules exceed “rationalized” risk assessments. They are highly symbolic and according to lawyers, reflect anxious clients' needs for control in an arena that is both legally and medically unsteady, and where they feel most vulnerable. Many of the rules described in this article are clearly too hard to police to be anything but symbolic, as several subjects confessed. They may express the power difference between parties to a peculiar, but increasingly popular, business transaction. Still, social actors are empowered in varying degrees, leading some to resist or push back against rules and forms of control. After all, surrogates carry the baby, and thus many of the proverbial cards. Power dynamics between the parties is another critical dimension of contracting that deserves separate and close scholarly attention.

Why are these rules and practices consequential? Whether realistically enforceable or not, feeling rules are influential and institutionalizing: formal contract provisions are developed, shared, and adopted in the field, not merely deployed on the individual level. They are diffusing across borders, given the unsettled legal environment, causing multijurisdictional practices to develop despite legal prohibitions.Footnote 6 Lawyers, matching agencies, and therapists socialize surrogates and intended parents—as well as other professionals—into an emotion culture through feeling rules embedded in contracts and their interactions along the way. They are key authors in scripting emotional performance and cornerstone social roles like motherhood, fatherhood, and family. They contribute to the expectations and terms of the contract among the parties, formalizing provisions and practices. Law casts intimate contact and emotional bonding between a mother and the child she gestates as emotionally “deviant.” Ironically, the mother-child bond is not deviant, but the norm calcified for centuries across cultures in most contexts except commercial surrogacy. Feeling rules, such as prohibitions on breastfeeding, do not simply resocialize the surrogate into detachment, but also legalize it: the rules are subject to sanctions for breach of contract.

Further, the widespread legality of surrogacy depends on normalizing a new and socially acceptable emotion culture. While policing separations between birth mothers and their children is not necessarily new, encoding them in enforceable contracts as feeling rules may be. However, law is not homogenous and is a contested terrain, making the negotiation for, resistance to, and enforcement of these rules complex and deserving study. For now it is clear that in managing risk and intention for parentage through the formal legalization of emotion, lawyers actively redefine and constitute broader social norms in the absence of informed collective agreement on the ethics and legality of commercial pregnancy.

Since surrogacy relations are steeped in emotion, it is an ideal site for studying how feeling rules in contracts are used to cope with significant legal ambiguity. Surrogacy as a case is certainly at one end of the “emotional” and “unsettled” spectrum among exchange relations. But emotions and legal certainty should be viewed as variables, present in differing degrees along a continuum. What about heated labor negotiations, mortgage lending, or premarital agreements? Surrogacy is one type of exchange relationship that highlights each of these variables in a particularly overt way. Although, by definition, only women can perform surrogacy contracts, I do not seek to reinstantiate an antifeminist paradigm that aligns women and emotions and outside of commercial life. Rather, I aim to illustrate through a particular case, which highlights these variables in action, just how “relational” contracting actually is.Footnote 7 Emotions have been neglected dimensions of exchange relations. While the pervasiveness of the legalization of emotion must be examined in different contexts in the future, I hypothesize that the differing degrees to which emotions and legal uncertainty are present in other types of exchange relations; one will also find contractual efforts to manage risk and vulnerability by managing feelings.