INTRODUCTION

Problem-solving courts face a quandary: the same qualities that enable the flexible and collaborative aspects of therapeutically driven specialty courts can also make them problematic for clients and potentially limit courts’ capacity to provide meaningful case resolution. There are at least three interrelated factors that both benefit and undermine problem-solving courts: the centrality of judicial authority, workgroup composition, and enforced compliance.

To begin, problem-solving courts offer judges a singular authority to use flexible and nonadversarial approaches to address client problems. In contrast to their traditional role as neutral arbiters of the law, judges overseeing these types of courts often fulfill multiple roles, acting as social workers who mandate treatment-like interventions and as probation officers who meet regularly with clients to ensure they are following through with plans (Castellano Reference Castellano2017, 417; Talesh Reference Talesh2007, 96). While research demonstrates that many courts effectively blend ideas from staff and clients, some judges may not have the temperament or skills to guide clients through treatment, and treatment-like interventions may invite longer or more invasive surveillance by the state (Aubin Reference Aubin2009; Lens Reference Lens2015, 5; McLeod Reference McLeod2012, 1621). There is also no guarantee that problem-solving judges who take on “bold, engaged, action-oriented norms” will do so in a way that addresses the root causes of problems, even in collaboration with community partners (Boldt and Singer Reference Boldt and Singer2006).

Collaborative partnerships are a hallmark of the therapeutic options available in problem-solving courts. Court workgroups typically include caseworkers, prosecutors, and defense attorneys, who use their expertise to represent their understanding of client needs in negotiations with other workgroup members. However, these parties are required to act within the norms of their professions, the boundaries of the judge’s inclinations, workgroup social biases, and the administrative constraints of each district court (Castellano Reference Castellano2011b; Gonzalez Van Cleve Reference Gonzalez Van Cleve2016). Further, legal professionals may view clients’ social group position as synonymous with the “problems” that render them unable to resolve their legal issues on their own, rather than seeing the perspectives of the clients as valuable in shaping more effective systems and procedures. There is an assumption that the judge or workgroup knows best, and that the client’s challenges in one area make them unable or unqualified to participate in deciding whether and what treatment is appropriate. The result is that, even if clients are “helped,” the system “happens to” them, as opposed to clients participating in problem solving.

Finally, the experimental development of these courts across locales has also led to diversity in where they lie on the spectrum of coercion, from enforced to self-initiated participation (Ahlin and Douds Reference Ahlin and Douds2021, 311; Dorf and Sabel Reference Dorf and Sabel2000; Tiger Reference Tiger2012). Many fall into a category that Rebecca Tiger labels “enlightened coercion,” in which participants must regularly return to court for a lengthy period of time to ensure compliance and graduate only after completing judicially crafted and court-ordered treatment (2012, 73). The authoritative stature of judges encourages client engagement; the judge’s attention and encouragement can be affirming and even inspiring for defendants (Aubin Reference Aubin2009). However, reliance on judicial authority stands in tension with best practices, which ideally create “a respectful, empathetic, non-paternalistic, and supportive environment where participants are actively engaged in the decision-making process and are persuaded rather than coerced into making behavioral changes” (Lens Reference Lens2015, 703).

In response to these challenges, this article suggests that the potentially intrusive and normative force of problem-solving courts may be countered by the procedural representation of those groups most affected by court decisions. Our research explores the founding and initial operation of Street Outreach Court Detroit, the city’s homeless court, and highlights the role of a social action, indigent-based membership organization in driving the court’s creation, shaping its structure, and establishing ongoing representation of affected community members. We observe that when a social action organization proposed the need for a particular model of specialty court, and cocreated its structure and processes, the new court’s procedures reflected the preferences of the affected population. The organization’s role was meaningful, in regard to both establishing the parameters for specific client case management (i.e., appropriate fines, community service expectations, etc.) and developing institutional guidelines and procedures. While social action groups typically gain attention for applying external pressure on power holders, this case demonstrates the role of an indigent membership organization in formalizing representation of member interests, through ongoing internal discussions over court design and process with legal professionals.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In the 1990s, as the United States reached new heights of mass incarceration, criminalized social welfare systems, and increased surveillance of low-income populations, state court systems concomitantly innovated specialty courts (Eubanks Reference Eubanks2018; Feinblatt, Berman, and Foxx Reference Feinblatt, Berman and Foxx2000; Gustafson Reference Gustafson2009). As primary witnesses to the failures of the criminal justice system in addressing community and public health concerns, judges have been leaders in the development of diversion and problem-solving courts, in the tradition of therapeutic and rehabilitative justice (Dorf and Fagan Reference Dorf and Fagan2003).Footnote 1 The role of judges as pivotal actors with the authority to institutionalize court reform has led to an ad hoc spread of specialty courts in the United States, based on the interests and initiative of individual judges (Castellano Reference Castellano2017, 399).

Eileen Ahlin and Anne Douds (Reference Ahlin and Douds2021) categorize thirteen models of problem-solving courts into three broad types: courts based on criminogenic needs (i.e., needs that may contribute to criminal behavior, such as drug addiction); courts based on individual characteristics, such as juvenile dependency, veteran status, or neighborhood (i.e., community courts); and courts based on types of criminal and civil offenses (e.g., gambling or domestic violence). These courts often share common features, such as implementing a collaborative, team-based approach, including social work or other treatment professionals in addition to the traditional judge, prosecutor, and defense attorney (Peters Reference Peters2013, 118; Winick Reference Winick, Richard and Eve2013; Talesh Reference Talesh2007). In treatment-focused courts, judges rely on social workers for case management—to help the workgroup interpret and make judgments about a client’s efforts, motivations, and likelihood of recidivism in the context of family, mental health, and other considerations.

It is common in problem-solving courts for judges and attorneys to shift roles, “largely repudiat[ing] the classical virtues of restraint, disinterest, and modest, replacing these features of the traditional judicial role with bold, engaged, action-oriented norms” (Boldt and Singer Reference Boldt and Singer2006). There are positive aspects to providing judges with such significant discretion in a therapeutic context. For example, Castellano observes that mental health court judges have been able to engage suggestions from clients in order to more effectively address issues or problems (2017, 417). Footnote 2 The incorporation of caseworkers brings more attention to the well-being of the client, expands service access, and shifts court dynamics toward broader community impact.

Beyond these similarities, problem-solving courts vary based on purpose, procedure, and context (McLeod Reference McLeod2012). Drug court clients, for example, are often referred to diversion programs by court personnel after having been arrested for or charged with a controlled substance–related crime (Lilley, DeVall, and Tucker-Gail Reference Lilley, DeVall and Tucker-Gail2019; Janetta, McCoy, and Leitson Reference Janetta, McCoy and Leitson2018; Griffin et al. Reference Griffin2018). Provided clients meet eligibility requirements, such as demonstrating that they do not have a violent criminal history, they are offered the opportunity to plead guilty and enter into a treatment plan that may last several months (Bozza Reference Bozza2007, 2; Meekins Reference Meekins2006, 16–17). Mental health courts, similarly, often institute a system of lessened or alternative sanctions to which clients agree in exchange for the opportunity to have a lesser sentence or to avoid jail time entirely (Bozza Reference Bozza2007, 3; Meekins, Reference Meekins2006, 16–17).

The community court model differs in that, typically, it is not a judge but community members who identify a criminal justice issue and then seek assistance from the court system in addressing the problem (Lee Reference Lee2000, 1–5). As Malkin (Reference Malkin2003) identifies, community courts generally share the objective of identifying “quality of life” offenses within communities and, based on community needs and preferences, instituting “meaningful sanctions” for offenders who commit those types of offenses (1575). Community courts are more comprehensive than those based on individual characteristics and able to incorporate services from what otherwise would be a variety of specialty courts. Exemplars Midtown Community Court and Red Hook Community Justice Center include a variety of staff to address mental health, addiction, housing, and employment concerns, as well as community engagement, to meet a wide variety of individual needs and ultimately change resident perspectives on the court (Connor Reference Connor, Eileen and Anne2021).

Given the diversity of court types and approaches, the mechanisms through which problem-solving courts reduce recidivism and support rehabilitation are unclear (Ahlin and Douds Reference Ahlin, Douds, Spohn and Pauline2019). Depending on each court’s purpose and eligibility criteria, positive outcomes are the result of a combination of deterrence effects, access to individualized services, frequency or quality of interaction with the judge or other court actors, or clients’ sense of procedural fairness and system legitimacy. And while identifying their successes, scholars have also noted that many problem-solving courts fail to reduce incarceration rates, improve public safety, or increase overall public health (Justice Policy Institute 2011, 1; Seltzer Reference Seltzer2005). Among the reasons identified for these failures is the comingling of sanctions and treatment; clients may avoid incarceration following a treatment program, but they remain under the umbrella of a largely adversarial and coercive system in which the authorities retain the power to deprive the client of liberty (Bozza Reference Bozza2007, 2; Justice Policy Institute 2011, 1; Miller Reference Miller2004, 1494–95; Seltzer Reference Seltzer2005, 585).Footnote 3

Ideally the teamwork base of problem-solving courts “create[s] a web of reciprocal accountability between courts, defendants and treatment providers that transcends the traditional adversarial roles in both civil and criminal courts” (Dorf and Fagan Reference Dorf and Fagan2003, 1508).Footnote 4 However, as Castellano (Reference Castellano2011a) explains, while caseworkers have a therapeutic orientation to court processes, they must advocate and negotiate within the strictures of court procedures and norms. Judges and lawyers, including defense attorneys, traditionally have a coercive and “social disciplinary model” approach to court procedure and decisions, even within a mental health court (McConvill and Mirsky Reference McConville and Mirsky1995). Within this context, Castellano writes, case managers must “tactically [position] themselves in opposition to both the court and the client” (489). Ultimately they “function as agents of the judiciary” (485).Footnote 5 These types of representation do not necessarily speak to the interest of the clients from their perspectives and lived experiences. Another reality of problem-solving courts is that the very characteristics that make such courts promising—offering treatment in lieu of sanctions, direct involvement by judges, systematic use of reward and punishment to motivate compliance—are also those that often are most problematic (Bozza Reference Bozza2007, 1).

A central but underinterrogated question is how “community” is defined in these models. Despite their individualized focus, Tiger describes drug courts as oriented toward public safety, justifying expansion of the court’s interest into numerous aspects of the client’s life “[b]ecause the addict’s behavior also affects other people, conceptualized as ‘the community’” (2012, 6). Similarly, in community courts, offenders often are tasked with “pay[ing] back” the community, defined as residents and stakeholders other than the defendant (Zozula Reference Zozula2018, 229). Community courts are sometimes criticized as expanding “broken windows” approaches to punishment of low-level crimes or deterring defendants from pursuing other means of resolution (Zozula Reference Zozula2018, 229–30). This perspective lacks recognition that a defendant’s ongoing entanglement with the criminal justice system—especially for those who have been accused and/or convicted for crimes of poverty—also has negative consequences for the broader community.

The Homeless Court Model

Given these critiques of problem-solving courts, and the subordinate status of defendants in the system, is reciprocal accountability possible within the courts? What types of organizational collaborations might hold court actors accountable to community-based visions of justice—that is, according not only to a singular, legal sense of public interest but to those communities most affected by the court’s decisions?

The homeless court model offers an approach to court-community relations that sheds light on the experience of marginalized groups in court systems and suggests a path for improved collaboration and accountability. Homeless courts share the therapeutic and collaborative aspects of other criminogenic courts, but have unique characteristics that potentially mitigate the coercive or entangling aspects of interactions with the justice system.Footnote 6 Most notable for our purposes is how this model developed out of the self-identified needs of homeless individuals.

The San Diego Homeless Court Program dates to the late 1980s, from a three-day event developed by Vietnam veterans called Stand Down, which connects homeless veterans to local services in a welcoming, accessible site. Through a survey, the organizers learned that one of the participants’ greatest needs was resolution of outstanding warrants. “In response, the San Diego Superior Court set up a court station at the event’s next annual meeting in 1989” (Troeger and Douds Reference Troeger, Douds, Eileen and Anne2021, 95). With guidance from the American Bar Association’s Commission on Homelessness and Poverty, variations on that initial model have since spread to twenty-one states; more than half of those documented by Troeger and Douds (Reference Troeger, Douds, Eileen and Anne2021) were established after 2010.

Perhaps the most significant difference between the homeless court model and most problem-solving courts is how a client is first introduced to the program. Homeless court clients are not diverted to a program in lieu of fines or custody, but rather they seek out participation as a means of resolving intersecting issues, sometimes years after conviction. Veterans and homeless courts operating in the Stand Down model seek to “resolve criminal cases of participants already engaged in program rehabilitative activities,” with referrals originating from homeless service agencies rather than within the court system (Binder and Horton-Newell Reference Binder and Horton-Newell2013, 3, emphasis ours). Steve Binder (Reference Binder2002) describes, “Monthly homeless court is more of a recognition court – recognizes that they’ve been in the program” and accomplished personal goals. Thus, many clients have demonstrated a willingness and capacity for reform well before formal involvement of court authorities (Mondry Reference Mondry2018).

In addition to self-driven involvement, lessening entanglement and bureaucratic burden is central to the homeless court model. Many specialty court processes require clients to return to the court several times—even monthly—prior to dismissal (Buenaventura Reference Buenaventura2018, 14; Nolan Reference Nolan2001, 94–95). As clients complete court-supervised programs, courts may employ “carrots and sticks” tactics, where failure to execute the treatment plan subjects the participant to more penalties, sometimes including jail time, than if they had not chosen diversion (Nolan Reference Nolan2001, 95; Zozula Reference Zozula2018, 235). Homeless courts, in contrast, employ a “pure dismissal” model, where clients only appear before a judge after having completed an action plan based on the defendant’s specific circumstances. Although the plan must be agreed to by the judge, it is generally drafted and overseen by a caseworker or service provider. Once the plan is complete, the participant comes before the judge, who typically dismisses the case after a single hearing (Troeger and Douds Reference Troeger, Douds, Eileen and Anne2021; Buenaventura Reference Buenaventura2018). Rather than meeting judicially imposed deadlines, homeless court clients usually work at their own pace to complete the treatment plan, with delay of resolution being the primary consequence for nonfulfillment of goals. Because clients ultimately come before the court having completed their sentence, there is no need to ensure compliance through additional hearings. Rather, programs concentrate on “what the defendant has accomplished on the road to recovery rather than penalizing him/her for mistakes in the past” (Kerry and Pennell Reference Kerry and Pennell2001, 3).

Part of what makes the Stand Down model uniquely effective for addressing the needs of a marginalized population is that it was designed to meet those community members on allied territory, in contrast to the experiences of indigent people in traditional courtrooms. Dorf and Fagan claim that problem-solving courts create “a web of reciprocal accountability between courts, defendants and treatment providers” (2003, 1508). But even among a collaborative workgroup, there is no position of security or power from within the court system in which the client can hold the other actors accountable or expect reciprocity. Even in most community court models, the problems to be solved are often identified by applying a public safety versus a client-centered rationale (Thompson Reference Thompson2002, 89). Tara Vaughn’s (Reference Vaughn2019) research finds that veterans’ intentions to seek help at Stand Down are strongly correlated with perceptions of established social support systems and self-efficacy. She also reports that “lack of trust, negative past experiences, lack of others caring or listening, and stigmatization” are the greatest interpersonal barriers to veterans’ seeking resolution of outstanding legal claims (54–55). Stand Down was innovative because the problem of outstanding warrants was identified by homeless veterans, and the court system adjusted its procedures to address that concern in community spaces that were welcoming and accessible to those participants.

Given the recent spread of homeless courts in the United States and the diversity of specialty court operations, we do not know the extent to which other such courts include purposeful identification of self-identified needs from clients in their respective communities. Social service agencies, while focusing on connecting clients to mental health treatment and other supports, may also be more accountable to other public stakeholders than to clients in the ways their programs are created and administered. For example, the homeless court program in Los Angeles requires clients to participate in a rehabilitative program for a period of time before earning eligibility, similar to most other homeless courts. But as Forrest Stuart has detailed, the city’s three mega shelters rely on arrests by the LAPD as “key points of intake and program enrollment” for their rehabilitative programs (Stuart Reference Stuart2016, 76). This public-private collaboration, named the Safer Cities Initiative, led to a dramatic rise in misdemeanor arrests in Skid Row.

The research literature on community organizing broadly distinguishes social action groups from social services and from community development corporations: the former bring people together to convince or pressure decision makers to meet their group-identified collective goals, while community development approaches focus on the use of cooperative strategies to build communal infrastructure (Staples Reference Staples2016). While these categories are useful as a matter of emphasis and distinguishing approaches to managing conflict, mobilization of marginalized communities often involves entwining basic needs, social service functions, and development functions with community organizing and social movement mobilization (Aaslund and Seim Reference Aaslund and Seim2020; Carroll Reference Carroll2015; Corrigall-Brown et al. Reference Corrigall-Brown, Snow, Quist and Smith2009; Fine Reference Fine2006). Social action organizations focus on individual empowerment, efficacy, and participatory decision making, both in internal discussions and external coalitions. Most research on social action groups focuses on their participatory processes, collective identity, leadership development, or public issue campaigns to influence policy makers, not the representation of socially marginalized groups within court systems.Footnote 7

In this article we analyze the role of a membership-based, social action organization as a primary agent in catalyzing and shaping Detroit’s homeless court, to meet the stated needs of its members. This case expands scholarly knowledge on the characteristics, benefits, and challenges of homeless courts as an innovative type of problem-solving court, and analyzes aspects of a court’s development and characteristics that could potentially mitigate the drawbacks of other problem-solving courts.

The Detroit Context and Community Organization

Detroit’s municipal bankruptcy in 2013 brought global attention to the city’s long-term economic decline—the result of economic structural disadvantage, state and national disinvestment, and regional racial balkanization (Galster Reference Galster and Doucet2017; Moskowitz, Reference Moskowitz2013). Low-income residents have disproportionately borne the burden of the city’s financial hardships. As in other municipalities across the United States, the urgent need to fund an expanding criminal justice system, coupled with implementation of aggressive broken windows policing, has proven to be a hazardous combination for those struggling economically (Harvard Law Review 2015). The burden is compounded for housing-insecure individuals, who may be “unaware of or unable to respond to [criminal charges] … resulting in bench warrants and crushing legal financial obligations” (Rankin Reference Rankin2019, 107–08). As Rankin observes, “Once individuals are saddled with a misdemeanor or a warrant, they are often rendered ineligible to access shelter, food, services, and other benefits that might support their ability to emerge from homelessness” (107–08). The “policing for profit” model, combined with gentrification of parts of the city and corresponding criminalization of homelessness, further entangles low-income Detroiters in the criminal justice system (Jay Reference Jay2017). Indigent residents, due to loss of driver’s licenses or fear of outstanding fines and warrants, are reluctant to report crimes to the police or otherwise participate in civic activities (Prescott and Bulinski Reference Prescott and Bulinski2016).

The 36th District Court of Detroit is one of the busiest courts in the nation, serving a city where close to 40 percent of residents are poor, yet legal counsel and aid programs are underfunded and understaffed (Aaron Reference Aaron2013; Warikoo Reference Warikoo2016).Footnote 8 Mismanagement of the court was a factor in the city’s bankruptcy; at the time of the filing, the 36th District faced a budget shortfall of $5 million and had failed to collect nearly $300 million in fines and tickets (Langton Reference Langton2013). Financial and administrative programs in the 36th District were placed under the oversight of a state-appointed special emergency manager, and the district court created a special collections docket in response to pressure from the state to increase revenue (Alvarez Reference Alvarez2017; Langton Reference Langton2013). At the same time, in the face of urgent needs to address poverty and recognition of the inability of many defendants to pay, judges in the 36th District Court have engaged in varied programs that use their discretion to address the city’s most significant problems. The 36th District offers several specialty courts, such as mental health, drug, veterans’, and community courts. Judges also engage in collaborative efforts with social and legal services agencies.

A uniquely grassroots and influential community organization working to address the criminalization of poverty in Detroit is the Detroit Action Commonwealth (DAC). DAC is a nonpartisan membership organization of more than five thousand mostly low-income or homeless Detroiters (Detroit Action Commonwealth 2019).Footnote 9 As one member leader said, “action is our middle name.”Footnote 10 Since the group’s founding in 2008, DAC leaders and organizers have been listening to the concerns of and advocating on behalf of soup kitchen frequenters, recruiting dues-paying members ($12 per year, payable in increments of 25 cents per week). DAC engages members in leadership training and personal group empowerment for direct action on issues of their choosing. Many of these issues revolve around involvement with the criminal and civil justice systems. Member victories have included improving conditions at homeless shelters, obtaining fee waivers for state identification for some indigent residents, and launching a successful “Ban the Box” campaign to prohibit initial background checks for municipal employment before determining applicant qualifications.

The DAC board consists of low-income individuals who use the soup kitchens on a regular basis. Weekly membership meetings for DAC are run by member leaders out of four Detroit chapters, including two Capuchin Kitchens run by friars in the Order of Saint Francis, one by St. Leo’s Soup Kitchen (formerly St. Leo’s Catholic Church), and one at the NOAH project for the homeless at Central United Methodist Church. Active members are generally familiar with the other kitchens but tend to affiliate with one chapter based on which they frequent for meals and other services. The organizers and elected representatives of chapters coordinate on issue-related actions and service projects.

Also addressing fines and fees are nonprofit organizations, such as Street Democracy, a legal nonprofit that describes itself as “working with the community to transform systems of oppression into systems of opportunity.”Footnote 11 Street Democracy (2018) engages in advocacy efforts around restorative justice and veterans’ programs as well as serving as defense counsel in the city’s homeless court, Street Outreach Court Detroit.

METHODOLOGY

This research is rooted in a phenomenological approach to understanding judicial institutions and political activism, focusing on participants’ experiences in their own terms, their reflections on interactions with each other in court and community settings, and the meanings they take from those interactions.Footnote 12 The research began with participant observation consisting of conducting intake interviews of applicants for Street Outreach Court Detroit (SOCD) at the St. Leo’s chapter of DAC and attending DAC membership meetings at Capuchin Soup Kitchens.Footnote 13 Observation was conducted for approximately six hours a week for four months in 2014 (about one hundred hours total). Throughout 2015–2016, the coauthors completed nineteen semistructured interviews that included primary collaborators involved in the founding and implementation of SOCD, as well as observing court hearings on site.Footnote 14 New contacts were identified through interviews with initial contacts in this densely interconnected network. Interviewees included two defense attorneys from Street Democracy, which represents the homeless court clients and serves as the administrative center and conduit for participating service agencies; two activist leaders from DAC—one the treasurer and one an internally recruited and paid organizer—both of whom joined DAC as frequenters of the Capuchin Soup Kitchen; one community organizer who helped found DAC and who continues as an informal advisor; two Detroit district judges and two magistrates; and two other legal professionals who advised the Detroit coalition, including one Ann Arbor judge of a similar court, and one lawyer who founded a similar homeless court in California. Other partners interviewed include a pro bono lawyer from a prominent Detroit law firm, a liaison to the Michigan Secretary of State, and five social service professionals conducting intake for the program, representing three different community agencies (Capuchin Soup Kitchen, Neighborhood Legal Services, and St. Leo’s Catholic Parish).Footnote 15 The city prosecutor who is a partner to this program declined to be interviewed.Footnote 16

To gather interviewees’ individual recollections of how the collaboration unfolded, the research relied on open-ended interview questions and the grounded theory approach to qualitative analysis (Strauss and Corbin Reference Strauss and Corbin1998; Charmaz Reference Charmaz, Jonathan, Harré and Van Langenhove1995). We used open coding to identify emergent patterns and then further coded and categorized the data along themes of decision-making processes, location and security, personal transformation, and the role of the activist organization in relation to that of legal professionals (Lofland et al. Reference Lofland, Snow, Anderson and Lofland2006).Footnote 17 We observed consistency and repetition across interviews, including how interviewees characterized the progression of the court and the types of disagreements that arose in workgroup discussions. In addition to the interview transcripts and written notes, we triangulated observations from community meetings within the soup kitchens, participant observation of program intake processes, and court hearings. We also triangulated information about court processes, participants, and goals across documents, including the community organization’s electronic intake forms, court administrative orders, and news coverage.

FINDINGS

Mary Jones was first referred to the Capuchin Kitchens for food, after her husband died unexpectedly in 2007 and the house she lived in was foreclosed on the following year. She returned to the soup kitchen with the intention to volunteer in food distribution, but was, in her words, redirected to involvement in DAC after chatting with board members during a meal. At the time of our interview, Jones was treasurer of the Conner Kitchen Chapter of DAC and of the overall organization. For Mrs. Jones, DAC offered an opportunity to give back and to serve in a leadership role because of its mission, which incorporates direct action, community development, and service delivery to meet member needs.Footnote 18 From her role as a DAC board member, Jones was one of the key members involved in the creation of the outreach court.

The following sections describe how DAC initiated and created an enduring partnership with the Detroit homeless court. The collaborative beginning, we argue, is not incidental to the court’s structure but served to prioritize the needs of the court’s target population. Then, based on this Detroit example, we describe how the homeless court model likely encourages participation in comparison to problem-solving models centered on diversion and enforced compliance. We also address obstacles that limit the potential for homeless court innovation, including resistant court administration, inadequate affordable and social housing, and the challenges facing organizations of low-income and indigent people.

A Collaborative Effort

In the late 2000s, DAC organizers met with members and others who frequent the soup kitchens to identify their primary concerns and research potential solutions. Member and organizer Clark Washington describes the organizing process.

We were noticing mainly how—it’s generally just the same people come into the soup kitchen almost on a daily basis. We started doing one-on-ones with ’em. Going out to the tables …. Go talk to the people. Then we did some surveys too. “What is the biggest thing holding you back? … ” “[If] I get my tickets paid off or if I could get my license and something, I could get a job.” Because there ain’t no jobs directly in the city …. We said, “Well, okay. Let’s see what we could do about it.”Footnote 19

Other organizers echoed that warrants and outstanding fines were barriers to housing and employment, including for leaders within DAC. For example, DAC’s vice president at the time could not find housing due to a misdemeanor on her record. Members avoided even entering the courthouse because of their fear of “being hauled away.”Footnote 20 Some members were not familiar with the front entrance to the 36th District Court, having only entered previously through the tunnel from the Wayne County Jail.

In researching obstacles to acquiring state identification, DAC leaders learned of the San Diego Homeless Court and sought the advice of its founder, Steve Binder. It took a conference call with Steve Binder in San Diego for the DAC leadership team to learn that Judge Elizabeth (“Libby”) Hines in Ann Arbor, just forty-five miles west of Detroit, had also established a domestic violence court and a homeless court.Footnote 21

Hines invited DAC members to watch a hearing, and over thirty members made the trip to Ann Arbor. Clark Washington recalled the experience in detail. The first person on Hines’s docket was a former truck driver who needed a license to return to work after completing a prison sentence. But he owed over $10,000 in traffic tickets, most of which had accumulated as additional fines while he was in jail. Washington recounted how the judge listed the man’s progress in gaining housing and employment through the program and stated she would dismiss all his fines. Washington was amazed.

I’m sitting there going, “This shit don’t happen in Michigan.” [Laughs] I actually said that direct in the courtroom. That man broke down in tears. He was in his 50s. I stood up to go shake his hand and everything to congratulate him. By the time I got there, I was crying with him. I didn’t even know the man [laughs] and I’m crying…. I said, “Hey, y’all, let’s go. I’m ready to get back to Detroit.” If I could get downtown to 36th District Court, if I could get one judge down there to do that for one person in Detroit what that judge just did for that man, that’d be a win for me.Footnote 22

Judge Hines emphasized the collaborative aspects of the court, describing how through a “team approach,” other district judges were soon communicating with social service agencies about homeless clients: “It gave us this whole new sentencing option to help people, all these different agencies we could refer people to. It was like this huge exchange of information…. It was this great collaboration that emerged.”

Organizer Molly Sweeney recalls, “We got back. We realized we needed to build a team of people that could build this. We agreed this was the way.” About three months into their efforts, they received a call from Judge Hines, who recommended they meet with attorney Jayesh Patel, a native Detroiter with a background in legal aid and a commitment to racial justice (Pursglove Reference Pursglove2015). Patel and a colleague founded Street Democracy, a nonprofit legal services and advocacy organization whose objective is to “identify and research the systems that perpetuate poverty and punish the poor … and works to craft, implement, test, and replicate remedies to those systemic causes” (Patel 2019). A self-identified “picnic table lawyer,” Patel had sought to set up a clinic in one of the Capuchin Kitchens. But he discovered that his clients needed more support before he could effectively address their complex legal issues. Though he was already working within the soup kitchen, he reflected, “If it weren’t for Judge Hines, I think they would’ve been spinning their wheels, as would I.”

With evidence in hand from the Ann Arbor and San Diego courts, DAC leaders pulled together their allies, including the Capuchin Brothers and Catholic clergy, to present their members with the information they had gathered. They agreed on the goal of building an outreach court but, as Sweeney recounted, they needed a partner inside of the 36th District. “How do we get someone from inside the court to be our champion? That was our first meeting.” Father Theodore Parker, pastor at St. Charles Lwanga Catholic ChurchFootnote 23 in Detroit and a longtime community advocate, is a member of DAC.

Judge Cylenthia LaToye Miller has served in the 36th District Court since 2006. She recalls, “Father Parker came up to me and handed me a flyer. He said, ‘I need you to go to this meeting tomorrow. They’re looking at trying to do something to help homeless people.’ Well, when your pastor asks you to do something, you do it. [Laughter] I said, ‘Sure.’” Judge Miller then attended the team’s second formal meeting:

I’m so forever grateful that I did …. They called the godfather of Street Outreach Courts [Steve Binder] in the country on the phone…. I was blown away by everything that I was hearing. I was so excited. I couldn’t believe it…. What they expressed was, “We’ve tried to talk to the folks at the [district] court. We’re just not getting anywhere…. We need your help.” Then in that moment, I understood why I was there…. They said they hadn’t really gotten anywhere with any of the prosecutors. They hadn’t gotten anywhere with anyone really … required to be at the table to make this happen. Having come out of the city administration before coming here, I knew all of the players we needed to get to the table personally. I knew I could access them.

She told DAC leaders that she would inquire with other judges and assess if there was interest from within the court administration.

Miller reported on their efforts at the next bench meeting of judges at the 36th District Court and engaged Judge Katherine “Kay” Hansen, Magistrate Charles Anderson III, and Magistrate Steve Lockhart, among others, who were necessary to create and run the specialty court. The team then worked for about fourteen months to bring together the necessary government and social service partners and agree upon the process and terms to make a specialty court viable (Thorpe Reference Thorpe2013). In addition to their partners from the Capuchin Kitchens and the Catholic Church, connections from Miller and other legal professionals led to partnerships with the City of Detroit Law Department, the Wayne County Prosecutor, the Wayne County Executive, the City of Detroit Parking Bureau, the Bodman law firm, Neighborhood Legal Services, and Southwest Solutions social service agency. Judge Hansen recalled, “we would meet every other week, once a month, at the Capuchin Soup Kitchen in a round—because round matters—and talk about how people would participate, what we wouldn’t take, and what we would do at the end, with the recognition that the judge could always say no.”

Institutionalizing Representation of the Affected Community

Interviews revealed that this was not the first time a coalition partner broached the idea of an outreach court in Detroit. Jean Griggs, community development manager at Neighborhood Legal Services (NLS), recalled that she had heard Binder speak in the mid-2000s, but thought “it was so far-fetched in this community.” Senior attorney John Holler III had written the chief judge at that time about the possibility of allowing clients community service to waive the cost of traffic violation fines, if he could establish to the judge’s satisfaction that this was a client in good standing. The judge responded no, that the law did not allow them to treat one client differently from another. “I couldn’t argue with her. I filed that among my little disappointments and defeats and we just marched on.”Footnote 24

DAC was a driving force in the creation of the specialty court because the group worked in coalition to institutionalize its ongoing representation in the structure of the court while also maintaining its independent public accountability to its members. In doing so, it pushed the court toward what one attorney referred to as “proper directionality”—that is, in the interests of housing-insecure Detroiters. While the district court is “tied to the past” as a precedent-driven institution, DAC presence serves as a “check when we need it sometimes” on the human impact of court procedures.Footnote 25 As the team considered the circumstances of specific clients, they faced eligibility and fairness questions and developed court rules and procedures over time. In this way, the outreach court is not unlike traditional courts where rules must be developed in response to the issues raised in particular cases. The difference, however, is who is at the table to discuss the human consequences of those decisions.

The following sections describe several topics of decision making in which DAC representation made a difference for court procedures and outcomes. These include decisions over the location of public hearings, the presence of armed security, and the question of a minimum fine threshold for eligibility.

Location

Initially the 36th District Court leadership was, in the words of one interviewee, “not receptive” to the SOCD project, despite the efforts of DAC and the eagerness of the judges and magistrates who sought to volunteer their time. According to Judge Miller, other court officials asked, “‘Why does it even have to be at a homeless shelter? Why can’t they come to the court?’ I’ll never forget there was a particular judge who made a comment, which was, ‘I don’t care if they come in a plastic bag of leaves. They [the accused] can come here’.” Judge Miller said she tried to explain:

“Well, yes, they can, but they won’t, because they don’t trust the court system. That’s what you don’t understand. They believe that when they come in our doors, they’re going to be locked up. They’re used to being locked up. They’re used to being told they have to pay hefty fines that they can never afford because they are homeless. They’re not inclined to come into this building. We are going to have to meet them where they are, at least until we can develop their trust.” What I was able to get accomplished that day, which was a miracle really, was a commitment that—okay, you can go on, and you can research and see if you can get the other people to the table that you need … to make this work. Then you can come back once you get answers to the security questions and whether anyone else is actually going to play in the sandbox with you guys in this program.

Here, the phrase “meet[ing] them where they are” applied not only metaphorically but literally.Footnote 26 The chief justice at the time, the Honorable Kenny King, was especially concerned about security for the judges and other staff if the outreach court was held off-site in the community. Sweeney recounts the significance of physical geography: “We heard from Steve [Binder] multiple times that some of the other [specialty] courts completely failed, especially in their launches, because they had sheriff’s cars outside or they had police presence.” The issue of location was contentious for the Street Outreach Court steering committee: “There were some people on our table who were just like, ‘Let’s just have it at the court. It’s easier … It’ll be closer to the records.’”

For the defense team from Street Democracy, there was a trade-off in getting the outreach court started as soon as possible for as many clients as possible, and holding it off-site in the soup kitchen. They figured they could start the program six months earlier without the difficulty of getting official approval to hold hearings outside the courthouse. In addition, an off-site street court must meet for fewer hours and therefore assists fewer clients, due to both the travel time required of the staff and the delay in the processing of documents after court proceedings. Defense counsel estimated they would be able to hear and process five more cases per session were cases heard on site. Further, documents from off-site do not get processed the same day as the hearing. In order not to pay for additional clerk time, the judges arranged for clerks to enter SOCD paperwork only after their other work was complete. Therefore, after a successful hearing, the clients would have to wait longer for their driver’s license to be approved—an estimated additional thirty to ninety days.

But, of course, clients first have to feel comfortable enough to participate at all. It is this perspective that the DAC members brought to the discussion. Patel reflects that the team “had a difference of opinion there … they [DAC] won on that. Because again, this is their court … Some of those things we’re [defense attorneys] like, ‘Yeah, we can give up’.” The group discussed the “trade-off between the court being able to hear more cases and more rapidly process decisions, versus the benefits of off-site location, the feel of the court.” Patel describes, further, “We’ll butt heads. Sometimes it’ll take three, four months of meetings to figure out which one we like until we get to rough consensus,” but the defense will find a way to make it work, “even if it creates way more work for us.”

In the view of one organizer, involvement in the outreach court has transformed the perspective and careers of local attorneys: “The way they thought about court, and the way they thought about decisions and how they should get made, has dramatically shifted.” In particular, collaborating in the court has affected the ability of legal professionals to

see what it’s like to be somebody else, in the shoes of DAC. And you know that your instinct as a lawyer might be right legally in the structures that are already provided, but that might not be what’s just and the people who need to make those choices are folks on the ground. Then we as allies need to make sure that we’re facilitating how to make that happen. Using our power to make that happen.

Defense attorney Patel explains that “if it’s outside of a purely legal context, then we put it to them,” referring to DAC leaders. Each participant giving up some control is “one of the unique things” about the court. And, “obviously the judges are the ones that are really giving up the control.”

An organizer explained, after much back and forth, that DAC “really put their foot down saying, ‘We started this process and we’re not building a court that’s going to be held in the [district] court. This is key to us so we need to actually figure out a way to make it work’.” The purpose of the steering committee’s discussion was

to really take consensus on, “Well, what do we think is actually going to serve the values of this court? … Here or there?” It [the Steering Committee] is a great structure for being able to continue to make sure that all levels of power are part of the decision making but that table continually was able to stay and be checked on who had the most power in this space and those who should have the most power are those who are most impacted. Those voices need to be heard the loudest. It’s not a traditional setting where the judge gets to determine everything … which I think was really key in our success and making sure that we’re still off-site.

These statements emphasize the group’s core belief that it is those closest to the problem, those experiencing it, who should take the lead in defining the solutions.

DAC partners organized a meeting for March 11, 2012, hosted by the Bodman law firm, to gain the approval of then–Chief Judge Kenny King. This meeting included a presentation by Steve Binder with DAC leaders sharing personal testimonies, including their fears of court security and of being arrested. DAC completed the meeting with an “ask” for “letting us be a court” (Molly Sweeney 10/10/16). “After hearing Steve say. ‘There’s been no issues across the country with these courts, … these people are trying to get their lives back on track. These aren’t menaces to society,’ King agreed and the court could officially begin holding hearings and offering relief.”

In the year following the court’s founding, with the outreach court in full swing, administrative difficulties at the 36th District required SOCD to meet in the courthouse for two months. According to an organizer,

It was a horrible experience. People got frisked on the way in. People were late coming in. They felt uncomfortable. There was so much work that had to be done beforehand. Just letting people know they’re safe and you’re with your person. If anything happens we’re with you or you’re with your caseworker. It just didn’t feel the same. After, we had a very frank discussion about nope, this is not gonna work. I mean we gave it a try.

This reflection demonstrates why the agreement to hold it off-site was necessary; it also shows the flexibility of all partners to try something, assess, discuss, and change course, with the experience of the clients at the forefront. This process of sharing information, negotiation, and compromise that took place in regard to the physical location of the court was repeated as SOCD began to take shape.

Armed Security

An ancillary debate to the court’s location at Capuchin Kitchen arose because of the soup kitchen’s stringent “no-weapons” policy. From the perspective of most in court administration, the presence of armed personnel is absolutely necessary to protect everyone in the courtroom. Certainly, judges are a prime target for aggrieved defendants. At the same time, security personnel evoke fears of arrest for many community members and their presence can discourage communication with representatives of the justice system. An organizer described concerns that the presence of security guards or police would make an off-site court “an unsafe space” for participants. And as one DAC member noted, “The whole point of Street Outreach Court Detroit was to bring the court to the people” (Markus Reference Markus2016).

The debates surrounding the issue of weapons made it clear that the definition of security was contested and reflected a disconnect among collaborating partners. Part of what made the experience so powerful for the DAC members was how Hines’s court addressed their fears of the traditional court system. Sweeney explains,

There was this feeling in the [Ann Arbor] court when we went to visit it … that this is a safe place, this is your court, this is a people’s court. You pay these taxes. You’re able to be here. This isn’t a place where we’re trying to be punitive. This is a place where we’re trying to support your pathway to becoming a fuller person or whatever your journey is as a human being.

Although the views of court administration ultimately won out, the ways in which symbols of security, such as firearms, are present during SOCD hearings are distinct from what one would see in the 36th District Court building. Once the team had committed to holding hearings off-site, Judge Miller asked Wayne County Sheriff Napoleon that a nonuniformed officer be designated to the program. This officer would carry a concealed weapon and travel in an unmarked vehicle. After that agreement, the team still gained clearance from the Capuchin Brothers for an officer to bring a concealed weapon, because of their no-weapons policy. Brother Conlin said, “for the sake of these people, we’ll compromise…. We said we can’t just stand up and demand everything be on our terms.”

The presence of plainclothes law enforcement has not appeared to deter clients and may be fostering improved relations between clients and law enforcement. Brother Conlin notes: “A lot of people from the kitchen will volunteer to help clear the tables out, set the chairs up, bring in the state flag. Then the sheriff comes in…. A lot of these people—normally in the kitchen, when I started, if the police walked in, about three-quarters of the place would clear out. Now, they all know the sheriff. He comes in once a month, and they talk to him.” From Conlin’s perspective, “the judges are safer than they’ve probably ever been, at the Capuchins. They’re really loved and cared for.”

Fines and Recidivism

While there was consensus on which community members should be considered eligible for the court—that is, homeless or housing-insecure Detroiters—there was disagreement over the minimum threshold for what fines were considered worthy of consideration for relief. This point of contention arose with an applicant who owed $45 in fines. The initial perspective of many members of the workgroup was that this was too small an amount to justify participation in the program. They questioned whether devoting the resources of the court to resolve a $45 fine was worth the effort, noting that this was too small of an amount to really be considered a burden. From the perspective of DAC members, according to Patel, “$45 is a lot when you’ve got $189 in food stamps as your income. You live on that.” After talking with other judges and courts around the country, DAC and the defense team “pushed back” and successfully advocated for no minimum financial threshold to participate in the court.

In another instance, the steering committee had to decide how to proceed when a client received a new traffic ticket while in the program. Some of the partners argued, “they’re out if they get a new ticket.” The defense attorneys objected, saying, “Hey, no. This is where they are. These are our clients. You should expect at least some of them to fail…. We’re going to hold this out there so they continue on this path.” In these situations, the intentional partnership among diverse representatives made the recognition of divergent interests possible, and as a result they found paths of compromise.

Another important conversation developed in regard to what happens to clients after participation in Street Outreach Court. In a traditional court setting, the resolution of a case signals the end of the court’s commitments to the defendant. SOCD, however, attempts to recognize that judicial resolution is just one piece of repairing their lives. Judge Cylenthia Miller states that what she believes is “the thing that separates our program from any street court program in the nation” is the holistic legal services, such as assistance with filing for bankruptcy or helping with child support matters, that clients are eligible to receive not only during but after participation in the court. Miller detailed how prosecutor Jacob Schwarzberg came to her during the creation process:

He said, “You know? I was at home thinking the other night, Cylenthia, that we should try to help them with their other problems once they get done with their problems here at the court that have to do with the misdemeanors and civil infractions.” I was like, “Like what other problems? We were helping them with their homelessness and their jobs.” He was like, “Yeah, but you know, they probably could have collection cases and garnishment actions and child support issues.” I was like, “Oh my God! I never thought of that.”

Judge Miller described how

[the prosecutor] went [and] got [Bodman law firm] to come onboard, so that once a person completes their readiness conference, then completes the hearing, everything’s dealt with from parking and our stuff, then they become eligible for free services…. Those lawyers voluntarily will walk them in to deal with their civil cases and get resolutions.

Clark Washington similarly describes how people “stick around” after resolution of their cases: “We tell ’em, this program is not just to get your license back. It’s to get your life back. When we get through with you, we don’t want you to have to look over your shoulder for anything and everything …. [W]e do keep in contact with ’em … until we make sure that they are all the way back.”

Institutional Limitations

In Wayne County, Local Administrative Orders (LAOs) govern the internal management of specialty courts, including drug, veterans’, and mental health courts. At first, SOCD operated outside any LAO. As noted by an agency partner: “[T]he relief is discretionary. It’s a matter of the grace of the court. You have no statutory right to this kind of relief.” After two years in operation without this documentation of officially sanctioned procedures, a new judge, Nancy M. Blount, was appointed chief judge of the 36th District. Judge Blount suspended the operation of SOCD, pending approval of an LAO governing operation of the court.

On July 27, 2017, leaders from DAC and Street Democracy testified before the Wayne County Board of Commissioners to advocate for restoration of the outreach court program. They received a unanimous vote in support and subsequently gained approval from the Michigan Supreme Court. This was a limited public advocacy role for DAC leaders involved in the court creation process; the power was still in the hands of the chief judge to oversee agreement of all partnering organizations on the terms of the LAO and sign for approval. In the two years that the program was on hiatus, clients whose cases were in progress had no choice but to wait for the judge’s decision whether to continue the program. Interviews shed little to no light into why a program that relies entirely on pro bono efforts of judges and other staff hit a roadblock. One service provider speculated that some judges within the district opposed offering relief to individuals and saw it as a form of unlawful special treatment.

Judge Blount ultimately signed off on the LAO in November 2017 after amending the court’s rules for eligibility, and SOCD began holding hearings again in early 2018 (ModelD 2018). The LAO requires applicants to complete community service with the city’s program department workforce crews in order to participate in the program.Footnote 27 Specifically, rules are waived if applicants are senior citizens, pregnant, or disabled, or if their job hours conflict with the workforce hours. Those who meet one of those conditions can contribute service hours at a nonprofit organization. For those not falling under those exceptions, the work hours must total 3 percent of the total amount of fines and fees owed; for example, a client owing $1,000 must complete thirty hours. Those who fall under an exception can perform service at a nonprofit such as the service providers in the program.

Because the requirements for community service are relatively new, there has not been enough time to assess the effect of these additional rules. According to program staff, most program participants thus far have not been affected because their jobs fall within the workforce hours or, in some cases, they fall into the other categories of exceptions.Footnote 28 However, unlike discussions about recidivism and minimum thresholds for participation, the imposition of community service requirements represents an important area in which advocates for indigent clients were less successful in negotiating on behalf of clients’ interests. An essential feature of SOCD has been its ability to avoid the punitive and stigmatizing aspects of the criminal justice system, fostering a collaborative environment that recognizes clients as stakeholders in the process.Footnote 29 One anonymous interviewee affiliated with the court observes that most tasks assigned to SOCD clients, such as applying for federal housing assistance or resolving bench warrants in other jurisdictions, require efforts that are unrecognized within the traditional criminal legal system, such as the “courage to go into another courtroom knowing they could lock you up.” The import of the imposition of workforce assignments, overseen by the Probation Department,Footnote 30 remains to be seen.

DISCUSSION

Our findings document the ways in which a social action organization catalyzed and shaped the court’s structure and procedures, including negotiations over location of court hearings and whether to create a minimum threshold of fine for eligibility. While we cannot say whether or how the court might have developed without the involvement of DAC, interviews provide evidence that their involvement shaped how defense attorneys thought about the purpose of the court and what they advocated for in discussions with the judges, magistrates, and prosecution. For example, while the legal team would have prioritized expediency in hearing and processing cases, DAC members prioritized community location as central to their sense of safety and accessibility, even if it meant fewer cases could be heard and relief would move more slowly. The debate over whether there should be a minimum threshold of fines to be resolved in order for clients to seek relief highlights the impact of collaboration. While working group members had a sincere desire to alleviate poverty, few of them brought to the table the lived experience of poverty. DAC leaders were able to represent and advocate from the clients’ point of view. They also used their networks to introduce key judges to the homeless court model, engage necessary stakeholders, and create momentum for those legal professionals to commit to this program.

Our findings also offer a glimpse of the disagreements and negotiations that occur in the process of creating a specialty court. Prior research has focused on partner discussions and decisions in relation to particular cases and differing professional perspectives on client behavior, sentencing, and available services. However, the court partners, rules for eligibility, and guidelines for sentencing or diversion options are generally taken as given. Our case demonstrates how court creation itself can be a setting in which community members most affected by court outcomes can play a significant role in, and even reshape, the justice system.

DAC representatives brought to court discussions knowledge of what the criminal justice system felt like to its members and therefore a better understanding of why its members avoid going to court (or even engaging in service programs that may include court surveillance). Empathetic, motivated court officials and defense lawyers working in legal aid continued to learn from the experience of indigent clients through discussions. Formalized representation of this community’s interests in the court, along with their partial independence, enabled a semblance of power from which to assert their needs and preferences.

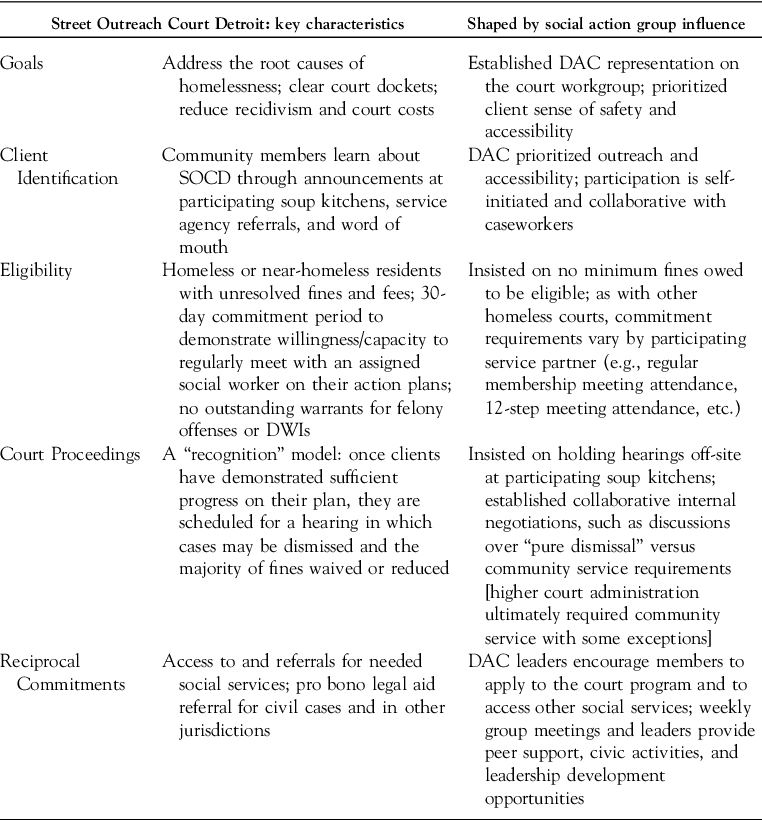

Building on the categories used by Troeger and Douds (Reference Troeger, Douds, Eileen and Anne2021), the following table identifies characteristics that are similar to those of other homeless courts and describes how the involvement of DAC influenced those elements (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Social Action Group Influence on the Outreach Court

Our findings delineate how the initiating role and involvement of DAC in the development of the homeless court led the court to foreground client needs. Iterative community discussions and workgroup negotiations involved all aspects of court operations, including goals, client identification, eligibility, proceedings, and commitments from all partners, including beyond the court itself. This dynamic approaches the “web of reciprocal accountability” that Dorf and Fagan (Reference Dorf and Fagan2003) describe as a best practice for problem-solving courts.

Judges and magistrates are accountable to DAC and the defense team to advocate for the maintenance of the homeless court within the administration and to adhere to the agreed-upon procedures collaboratively devised by the workgroup. SOCD attorneys represent their clients in the court and continually communicate with service partners to revise intake forms and best advocate for clients; further, the attorneys refer clients to pro bono attorneys for civil cases after resolution of their criminal cases. The legal defense team has added a recent graduate of SOCD to the Street Democracy board, overseeing decisions such as the hiring of defense attorneys for the court. DAC representatives also are accountable to their membership within and apart from the outreach court; they work with other DAC leaders and organizers to maintain the weekly chapter meetings, share information about social services, and encourage member participation in a variety of forms of civic engagement—from neighborhood beautification to candidate forums to coordinated attendance at city council hearings.Footnote 31 The group’s political independence from the court system makes reciprocal commitments and accountability among SOCD partners more meaningful, since the organizational space holds open the possibility for the group’s future self-identified needs to be heard and addressed by the courts.

These findings suggest that the institutional representation of a social action group in a court workgroup may mitigate the coercive aspects of problem-solving courts. While judges retain the authority to make final decisions, the self-driven and collaborative aspects of homeless courts reduce the possibility of program requirements or sentences that would ultimately further entangle clients in the justice system. The pure dismissal model enables judges to draw from the experience of caseworkers and community representatives earlier in the case review process and then play a publicly ceremonial and motivational role.

It is common in the specialty court model for social service partners and other community organizations to play the central role in assessing clients’ health, economic, and social needs, connecting them to resources and maintaining accountability. While caseworkers and defense attorneys use their expertise to represent client interests, they do so within their own professional focus and the constraints of the court system. In SOCD, leaders directly represent and advocate for members’ group interests in the court workgroup. This representation is distinct from how the defense attorneys represent clients to the court; representatives of DAC descriptively and substantively represent the interests of their members to the court.

CONCLUSION

Scholars examining procedural justice in problem-solving courts emphasize the quality of courtroom interactions and relationships between the judge and the defendant—whether the latter feels heard, supported, and respected by the judge when discussing their case. This article focuses on a step prior to those interactions, on the creation of the structure and processes that will guide the courts’ future interactions and decisions. Existing scholarship has highlighted limitations on the ability of problem-solving courts to address root causes of poverty due to their coercive elements and due process concerns. Building on that work, this article considers the social position of stakeholders as relevant to workgroup dynamics. While unequal legal power between courtroom officers and the accused is necessary for the courts to make enforceable rules, unequal social power undermines the ability of a problem-solving court to recognize client needs and meet its stated goal of addressing root causes of criminalized behaviors.

We argue that the permanent representation of advocates chosen by indigent-led community organizations may better equip problem-solving courts to address the root causes of poverty—at least those causes that fall under the purview of criminal justice institutions. While defense teams and case managers focus on advocating for particular clients, representative outsider voices are more likely to foster procedures that respect clients’ social position and experiences. Representation of a social action organization in a court workgroup maintains the ultimate authority of the judge, but it also shifts the workgroup dynamics by putting court procedures on the table for negotiation and creates the opportunity for mutual accountability across workgroup members. In doing so, the direct representation of indigent interests may relieve pressure from other team members, whose roles put them in the contradictory position of both advocating for clients and maintaining their professional legitimacy (Castellano Reference Castellano2017).

Our primary theoretical contribution is to reframe the limitations of problem-solving courts as lack of representation of, and accountability to, those individuals most affected by court processes and decisions. We observe that when a community activist organization cocreated a specialty court with attorneys, their representatives prioritized the knowledge, experiences, and preferences of the affected population.Footnote 32 Their role was meaningful both regarding specific case management (i.e., appropriate fines, community service expectations, etc.) and in developing institutional procedures. This suggests that a community group’s representation in the case workgroup may begin to challenge the class biases and oversights of district court systems, and get to the root of problems from the perspective of the individuals whose behavior is in question. Ahlin and Douds summarize that problem-solving courts “attempt to break the cycle of crime by solving whatever ‘problem,’ or social issue, is believed to be causing the criminal behavior” (2019, 342). Without the inclusion of perspectives of those most affected, the problems to be solved in problem-solving courts risk being those that are prioritized by court officials and service agencies rather than by the clients, thus undermining the courts’ inclusive mission.

Homeless courts with the pure dismissal model are unique in that there are typically fewer interactions with the judge compared to other therapeutic courts. The crimes of homeless court clients are often related to living in poverty rather than harm to other individuals, and reflect the prevalence of ordinances that criminalize poverty (Herring, Yarbrough, and Alatorre Reference Herring, Yarbrough and Marie Alatorre2020). Research on drug courts has demonstrated how the combination of therapeutic and procedural interventions of problem-solving courts increase system legitimacy and trust; ongoing judicial involvement shows an interest in client lives beyond wrongdoing and helps clients commit to treatment (Gottfredson et al. Reference Gottfredson, Kearley, Najaka and Rocha2007). But the benefits of repeated interactions may not extend to all client situations. An individual who was fined for multiple traffic offenses because they couldn’t afford to renew their license does not necessarily need more involvement with the justice system to demonstrate commitment. Further judicial interactions that do not address the problem directly (i.e., inability to pay) could potentially reduce trust in the courts. For indigent clients, perhaps it is not the repeated interactions with the judge that lead to more positive outcomes but rather the availability of financial relief and accessible court operations that reflect clients’ lived realities.

This research raises a question of which parts of a community are represented in collaborative, court-community programs. Representation of “community” interests within court systems may refer to a broad spectrum of organizations, including combinations of service providers, community development agencies, community building efforts, as well as hybrid models and political organizing for social justice. Organizations that actively engage community members also vary in the extent to which they exist in dependence, collaboration, or tension with the state (Arnstein Reference Arnstein1969). These qualities will affect a group’s capacity and likelihood of collaboration with court officials. Meanings of “community” are often contested and subject to manipulation by political actors (DeFilippis, Fisher, and Shragge Reference DeFilippis, Fisher and Shragge2010). This has special significance when working with historically excluded, economically marginal, and transient populations who have limited pathways to institutional influence. Future scholarship on court and community partnerships should further differentiate among types of courts’ community partners and their relationships with the clients or members they purport to represent, as well as the quality and extent of communication among collaborators and forms of accountability.

While this article contends that ongoing representation of a community-based membership organization can improve court procedures, we do not take for granted the challenges of democratic organizational development in low-income communities. The obstacles to maintaining representative organizations of, by, and for indigent people are likely a key reason why this kind of collaboration is rare. Greg Markus has written on these challenges for DAC. He explains,

DAC’s core constituency is highly transient. We are continuously engaged in finding and developing new leaders to replace ones who move on, sometimes to new and better lives and sometimes not. The personal struggles of impoverished, vulnerably housed leaders, nearly all of whom have lived their entire lives within an environment of structural poverty and racism, challenge our capacity to operate smoothly and efficiently as an organization, just as they challenge the capacity of our leaders and members to live their lives in peace and health.

The long tenure of a few key DAC leaders and organizers, as well as ongoing relationships among attorneys, caseworkers, and clients in the soup kitchens, helped maintain DAC’s collaboration with the court. Additionally, the fact that DAC has been able to persist despite these obstacles reflects in part their combination of social action, leadership development, and tangible benefits, such as access to state identification and clearing warrants and fines through SOCD. How service partners can best support inclusive civic work, and what is required for effective representation of marginalized groups both inside and outside of courts, are important questions for future research.

In 2020, the Detroit Housing Commission opened its housing voucher wait list to applicants for the first time in five years. The last time it was open, about forty thousand people entered the lottery for seven thousand spots on the waitlist (Abbey-Lambertz Reference Abbey-Lambertz2020). This is to say, the availability of local resources is a perpetual constraint on the effectiveness of problem-solving courts. Caseworkers can ensure that clients take proactive steps toward meeting their basic needs but they cannot guarantee that those needs will be met in the long term. There is need for more research identifying the range of community resources realistically available to homeless court clients based on the communities in which they reside, the combination of partners, as well as the worldview of those partners on what kinds of problems should be addressed by the court.