Article contents

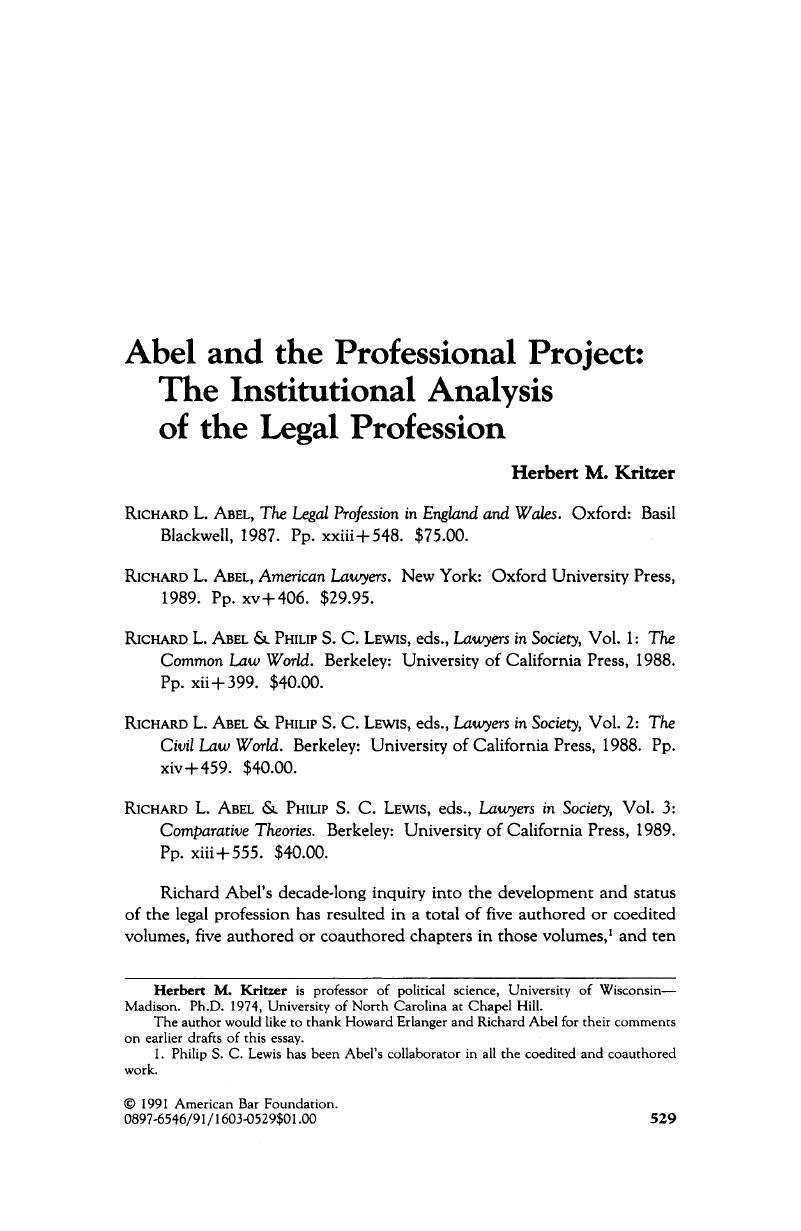

Abel and the Professional Project: The Institutional Analysis of the Legal Profession

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 December 2018

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essay

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Bar Foundation, 1991

References

1 Philip S. C. Lewis has been Abel's collaborator in all the coedited and coauthored work.Google Scholar

2 I have omitted from the list several articles on legal education that do not relate to the discussion in this review essay.Google Scholar

3 Readers interested in a more extensive treatment of Abel's theoretical approach should see Susan Sterett's recent essay in this journal,” Comparing Legal Professions,” 15 Law & Soc. Inquiry 363 (1990).Google Scholar

4 The term “professional project” is used throughout Abel's work to refer to what Abel sees as the profession's effort to secure market control through the control of the production of producers and the production by producers.Google Scholar

5 Throughout this essay, I will use short abbreviations in my citations to Abel's work. These abbreviations are defined in table 1.Google Scholar

6 Margali Sarfatti Larson, The Rise of Professionalism: A Sociological Analysis (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977).Google Scholar

7 The significance of monopolization in the drive for institutionalization of the medical profession in the United States is one element (among many) in Eliot Freidson's seminal analysis, Profession of Medicine: A Study of the Sociology of Applied Knowledge (New York: Dodd Mead, 1970), and was the focus of Jeffrey L. Berlant's comparative analysis of medical professions in the United States and Great Britain, Profession and Monopoly: A Study of Medicine in the United States and Great Britain (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973) (“Berlant, Profession and Monopoly”).Google Scholar

8 Sir Henry Benson, Royal Commission on Legal Services: Final Report (London: HMSO, 1979) (”Royal Commission”).Google Scholar

9 Abel has not ignored alternative theoretical perspectives on professionalism. In the introductory chapters of his books on lawyers in England and Wales (England) and on American lawyers (AmLaw), Abel delineates frameworks based on Marxist theory (i.e., the legal profession's place in the class structure) and based on Durkheimian structural-functionalism i.e., the legal profession as a self-regulating community that serves the larger social community). Even though he considers these frameworks at various places in his work, his dominant concern is with Weberian market control theory; this can be seen in his final overview essay, which he describes as having two objectives: “to illustrate the insights that can be derived from comparative analysis of legal professions and to test the power of a theoretical framework that emphasizes market control” (CompSoc 2 at 135, emphasis added).Google Scholar

10 Abel also acknowledges the importance of Durkheimian concerns about social order and stratification and Marxist concerns about the relationship of professionals to the means of production (id.).Google Scholar

11 It would be a gross oversimplification to say that Abel's analysis was limited to market control. Other significant themes in his work on the legal profession include (1) internal differentiation of the profession, (2) evolution in the structure of units of production, (3) socialization of the profession, and (4) professional self-regulation.Google Scholar

12 Weberian theory and the market control perspective have a clear interrelationship. iserlant, in Profession and Monopoly, specifically applies what he terms the “Weberian theory of monopolization” to the “study of the institutionalization of the medical profession.”.Google Scholar

13 See Com Law Wld for applications of the perspective by others to other common law countries.Google Scholar

14 Actually, in this essay, one of the last that he wrote in the series covered by this review essay, Abel does acknowledge that the market control framework is problematic as applied to the civil law world.Google Scholar

15 Part of the drop probably results from internal competition related to relaxed rules concerning advertising.Google Scholar

16 See also Domberger, Simon& Sherr, Avrom, “The Impact of Competition on Pricing and Quality of Legal Services,” 9 Int'l Rev. L. & Econ. 41 (1989).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

17 Abel seems to acknowledge that there may be a problem in ComgSocs, but he goes on to assert the general usefulness of his approach.Google Scholar

18 Perhaps the most visible interest is among state theorists, best captured in Peter Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, & Theda Skocpol, eds., Bringing the State Back In (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985). One of the essays in the third volume edited by Abel and Lewis is Dietrich Rueschemeyer,” Comparing Legal Professions: A State-centered Approach,”Comp Theory at 289. As is true of a number of the essays in the three volumes, aversion of this essay appeared previously as a journal article,” Comparing Legal Professions Cross-nationally: From a Professions-centered to a State-centered Approach,” 1986 A.B.F. Res. J. 415. Rueschemeyer proposes a state-oriented institutionalist approach to the legal profession; while that approach has merit, one need not orient an institutional analysis around the state.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

19 March, James G.& Olsen, Johan P., “The New Institutionalism: Organizational Factors in Political Life,” 78 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 734 (1984).Google Scholar

20 Some writers have used the term institutions to include virtually any stable pattern of behavior or interpretation; see Smith, Rogers M., “Political Jurisprudence, the ‘New Institutionalism,’ and the Future of Public Law,” 82 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 89 (1988). It is not necessary to go that far for the purposes of my discussion.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

21 Another way to differentiate between metainstitutions and basic institutions is to assess the degree to which the institution is linked to specific goals, with metainstitutions more geared to creating a “context”; for example, the market creates a context whereby firms can develop and flourish and in which consumers can express their preferences and satisfy their wants. In contrast, basic institutions are more instrumental in nature (e.g., IBM uses the market as a setting in which it seeks to maximize its profit and to assure its continued prosperity and existence). Metainstitutions serve something of a coordinating function, with rules and structures that tend to be more abstract than those of basic instititutions. The metainstitution is concerned with “how to do things”; the basic institution is concerned with “what to do.” This distinction is not without problems. What constitutes a “goal” may be in the eye of the beholder. Does the market have a goal? No: it simply creates the context for the firm, or Yes: it seeks to assure that goods and services are produced and distributed in a coherent fashion. Does science have a goal? No: it is simply a definition of a style of inquiry, or Yes: it seeks to advance knowledge systematically. Furthermore, an institution can function at multiple levels. For example, IBM sells computers, but it also creates standards that other computer makers have to confront and deal with.Google Scholar

22 March & Olsen, 78 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. at 734.Google Scholar

23 Underlying many of those issues, as well as other perspectives on institutional analysis, are what I would term the four key concepts of institutional analysis: Goals: Institutions have a mix of goals that combine internal imperatives (organizational maintenance, organizational growth, the needs of the institution's staffpersons) and external needs (e.g., serving a clientele, maintaining viable relationships with other institutional actors in the arena in which they function). Roks: In looking at the actors who work within an institution, a key distinction is made between the individual and what that individual is supposed to do (including what is to be done, how it is done, when it is done, and why it is done). Rules: Rules provide the framework for relationships among roles, definitions of how roles are to be carried out, and methods for dealing with failures of roles being carried out appropriately. Rewards: There must be incentives for individuals within roles to carry out their duties responsibilities; the rewards that comprise these incentives can be either positive or negation.Google Scholar

24 My favorite examples of this imperative involve the evolution of theater companies, which frequently start out as the vision of one person (or a small group of people) but, if successful, must at some point “institutionalize” the operation. While moving to some protoinstitutional form is often fairly easy (e.g., establishing some formal group structure), the need to institutionalize in the more complete sense often has devastating effects on the creative enterprise, and small struggling companies that have mounted remarkable productions on minimal budgets in marginal performance spaces often become artistic travesties when they achieve success, move into beautiful theaters, and try to mount large-budget shows. For a description of a theater company that has successfully made the first transition and is now in the midst of the second, see Susan Andrews,” The Board Is Taking Center Stage,”N.Y. Times. Dec. 2, 1990 (Magazine: The Business World), at 40.Google Scholar

25 Polsby, Nelson, “Institutionalization of the U.S. House of Representatives,” 62 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 144 (1968). A recent study of the British House of Commons found important differences between that House and the American House of Representatives in the specifics of institutionalization; see Hibbing, John, “Legislative Institutionalization with Illustrations from the British House of Commons,” 32 Am. J. Pol. Sci. 681 (1988).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

26 The control of production by producers is in part an effort to deal with the inevitable problem of all monopolies: where overall supply is restricted, individual suppliers can readily advance their own interest by overproduction or by stimulating supplier-specific demand (for example, by cutting prices).Google Scholar

27 Specifically, how does one account for the increasing pressure to end the distinction between barristers and solicitors in England? This would seem to represent a potential decrease in complexity and differentiation; in fact, other forms of differentiation better serve the institutional need to rationalize internal form.Google Scholar

28 See also Lady Marre, Time for Change: Report of the Committee on the Future of the Legal Profession 173–76 (London: General Council of the Bar and Council of the Law Society, 1988) (“Marre Report”), or Royal Commission 398–401 (cited in note 8).Google Scholar

29 Marre Report 175.Google Scholar

30 Competition with accountants has been a major issue for solicitors (England at 186–87); Abel noted this specific concern in our correspondence.Google Scholar

31 In our correspondence, Abel also pointed to a similar concern by barristers vis-à-vis large firms of solicitors.Google Scholar

32 The other major aspect of controlling production by producers concerns how members of the profession deliver their services. This, in turn, has to do with self-regulation, one important aspect of which is the control of internal competition, typically by defining undesired competition as a violation of professional ethics. Abel raises this issue in his discussion of the use of ethical norms to control things like advertising (AmLaw at 120–21; England at 190–91), but it is not a central focus of his discussion of self-regulation (AmLaw at 142–57; England at 133–36, 248–58). In Berlant, Profession and Monopoly 64–127 (cited in note 7), the author considers at some length the connection between “medical ethics and monopolization.”.Google Scholar

33 E.g., Brian Abel-Smith & Robert Stevens, Lawyers and the Courts: A Sociological Study of the English Legal System, 1760–1965 (London: Heineman, 1966) (“Abel-Smith & Stevens, Lawyers and the Courts”).Google Scholar

34 One might ask about wills and probate (what is known in England as the “law of succession”), which is another area that receives substantial attention from legal professionals. I would subsume this under the broader issue of property, since “succession” historically was concerned largely with who succeeded in the ownership of property.Google Scholar

35 The essay on the legal profession in Australia suggests that lawyers in that country are similar to lawyers in the United States in their zeal for finding new areas of practice; David Weisbrot,” The Australian Legal Profession: From Provincial Family Firms to Multinationals” (ComLawWld at 244, 294) (“Weisbrot, ‘Australian Legal Profession’”).Google Scholar

36 This phrase is taken from the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, written by John Adams originally for the Novanglus Papers. The opening clause of the constitution was: “In the government of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts the legislative, executive and judicial power shall be placed in separate departments, to the end that it might be a government of laws, and not of men.” See Page Smith, John Adam 441 (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Co., 1962).Google Scholar

37 Americans view themselves as “citizens of the United States,” while Britons think of themselves as “subjects of the British Crown.”.Google Scholar

38 As Abel notes (Market at 307), solicitors have not restricted their attention only to the litigation context, but this has been the most visible and public area of discussion. See, for example, Law Society, Improving Access to Civil Justice: The Report of the Law Society's Working Party on the Funding of Litigation (London: The Law Society, 1987).Google Scholar

39 In England, the rationalization of internal forms can also be seen in the recognition of the importance of alternative practice settings and the role of paraprofessionals working in legal practice settings. The transformation of “managing clerks” in firms of solicitors into “legal executives” is one example (England at 207–10) of the latter phenomenon; the increasing incomes and importance of the barrister's clerks as the size of “sets” (i.e., groups of barristers working in one “chamber,” or set of rooms) has grown is another (England at 103–10). See also Flood, John A., “Middlemen of the Law: An Ethnographic Inquiry into the English Legal Profession,” 1981 A.B.F. Res. J. 377; or Id., Barristers' Clerk: The Law's Middlemen (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1983). Legally qualified persons work in a variety of settings other than traditional firms. These range from the “law centres,” which employ solicitors to provide services to low-income communities, to solicitors and barristers employed by industry and government. The various groups may perform different kinds of tasks, and they frequently have divergent interests and concerns.Google Scholar

40 See Anne Boigeol,” The French Bar: The Difficulties of Unifying a Divided Profession” (CivLawWld at 258, 262–65) (“Boigeol, ‘The French Bar’”).Google Scholar

41 See Carlos Validás Jene,” The Legal Profession in Spain: An Understudied but Booming Occupation (CivLawWld at 369, 369–70).Google Scholar

42 See particularly Abel-Smith & Stevens, Lawyers and the Courts; and Royal Commission 25–27 (cited in note 8).Google Scholar

43 Most recently, see Lord Chancellor's Department, The Work and Organisation of the Legal Profession (London: HMSO, 1990) (“Work and Organisation”). For earlier discussions, see Royal Commission 187–202; and Marre Report 177 (cited in note 28). For a description of the machinations of division and fusion in the professions in the Australian states, see Weisbrot,” Australian Legal Profession,” at 248–55.Google Scholar

44 No doubt the primary reason for the continued division is the combined opposition by bench and bar (the former virtually all having previously been members of the latter).Google Scholar

45 See Great Britain Review Body on Civil Justice, Report of the Review Body on Civil Justice 16–35 (London: HMSO, 1988); and Work and Organisation.Google Scholar

46 I should also note that the preservation of the distinction between barristers and solicitors reflects in part the continuation of the social hierarchy that has traditionally marked English culture, with barristers comprising the “senior” branch drawn from the classically educated aristocracy and solicitors the “junior” branch with a more vocational emphasis. One aspect of institutionalization is the breakdown of differentiation based on social stratification in favor of a more functional basis of differentiation. Vittorio Olgiati and Valerio Pocar emphasize this change in their essay,” The Italian Legal Profession: An Institutional Dilemma” (CivLawWld at 336).Google Scholar

47 Boigeol,” The French Bar” (CiwLawWld at 258, 262–65); see also Thanh Trai Le, Tang Thi, “The French Legal Profession: A Prisoner of Its Glorious Past?” 15 Cornell Int'l L. J. 63 (1982). As Le points out (at 85), avoués have not completely disappeared; they continue to practice at the appellate level. Their continued existence may reflect in part the fact that avoués like notaires, are ministerial officers who essentially own the position (and have the effective right of selling the office upon retirement), while avocats qualify for their positions by meeting requirements of education, prior occupation, and character.Google Scholar

48 See Suleiman, Ezra N., “State Structures and Clientelism: The French State Versus the ‘Notaires,’”17 Brit. J. Pol. Sci. 257 (1987); or id., Private Power and Centralization in France: The Notaires and the State (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

49 John P. Heinz & Edward O. Laumann, Chicago Lawyers: The Profession of the Bur (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1982).Google Scholar

50 For a similar discussion of the stratification within the Canadian bar, see Harry W Arthurs, Richard Weisman, & Frederick H. Zemans,” Canadian Lawyers: A Peculiar Profession” (ComLawWld at 123, 151–58); or the earlier version of their essay,” The Canadian Legal Profession,” 1986 A.B.F. Res. J. 532.Google Scholar

51 While the clientele of such firms have been distinctive for a long time, limitations on the size of partnerships (a maximum of 20) up until 1967 (England at 201) prevented the firms from growing into distinctive institutions.Google Scholar

52 See, for example, Hazel Genn, Hard Bargaining: Out of Court Settlement in Personal Injury Actions (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988).Google Scholar

53 As Andrew Abbott points out, a norm restricting a practicing solicitor to a single articled clerk effectively limited the rate at which the solicitors' profession could grow. See The System of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor 252 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988) (“Abbott, System of Professions”); or id., ”Jurisdictional Conflicts: A New Approach to the Development of the Legal Professions,” 1986 A.B.F. Res. J. 187, 196.Google Scholar

54 From the various essays in ComLawWld and CivLawWld the only other country that appears to have had a comparable increase in the number of law schools is Australia; see Weisbrot,” Australian Legal Profession,” at 244 (cited in note 35).Google Scholar

55 As Abel notes (England at 265), the big changes started in the 1960s, which was just the point when the baby boom generation was approaching school-leaving age.Google Scholar

56 The increasing access to university education probably accounts for much of the rapid increase in numbers of law-trained persons in many countries: regarding Belgium, see Luc Huyse,” Legal Experts in Belgium” (CivLawWld at 225, 229); regarding the Netherlands, see Kees Schuyt,” The Rise of Lawyers in the Dutch Welfare State” (CivLawWld at 200, 206–7).Google Scholar

57 This no doubt partly reflected the baby “bust” of the depression years and World War 11, which kept the pool of potential applicants relatively small through the 1950s and into the 1960s.Google Scholar

58 World Almanac, The World Almanac and Book of Facts 1990 179 (New York: Pharos Books, 1969).Google Scholar

59 Interestingly, one of the consistent patterns documented across many of the countries described in ComLawWld and CivLawWld is the opening of the profession to women. For discussions of the implications of this broad change for the profession and for the practice of law, see Carrie Menkel-Meadow,” Feminization of the Legal Profession: The Comparative Sociology of Women Lawyers” (Comp Theory at 196); id., ”The Comparative Sociology of Women Lawyers,” 24 Osgoode Hall L.J. 897 (1986); or id.,” Portia in a Different Voice: Speculations on a Women's Lawyering Process,” 1 Berkeley Women's L.J. 39 (1985).Google Scholar

60 Abel also reports some striking fluctuations in recent years (e.g., a drop in Washington state from a 70% pass rate in July 1984 to 47% the following year) that he implies reflect decisions to reduce admissions to the bar.Google Scholar

61 The “leaders” of the profession also sought to erect barriers to entry for persons from undesirable social groups—primarily immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. See Jerold S. Auerbach, Unequal Justice: Lawyers and Social Change in Modem America 106–20 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976). However, this was done largely through citizenship requirements that persisted until they were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1973 (AmLaw at 68).Google Scholar

62 Abel cites the cases of Bernardine Dohrn, who was a member of the Weather Underground during the 1970s, and David Fine, who was one of the participants in a bombing at the University of Wisconsin in 1970 (AmLaw at 70).Google Scholar

63 See also C. J. Dias, R. Luchham, D. O. Lynch, and J. C. N. Paul, eds., Lawyers in the Third World: Comparative and Developmental Perspectives (New York: International Center for Law in Development, 1981).Google Scholar

64 Jon T. Johnsen,” The Professionalization of Legal Counseling in Norway” (CivLawWld at 54).Google Scholar

65 Erhard Blankenburg & Ulrike Schultz,” German Advocates: A Highly Regulated Profession” (CivLawWld at 124).Google Scholar

66 Kehei Rokumoto,” The Present State of Japanese Practicing Attorneys: On the Way to Full Professionalization?” (CivLawWld at 160).Google Scholar

67 Abbott, System of Professions 2 (cited in note 53).Google Scholar

- 6

- Cited by