No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

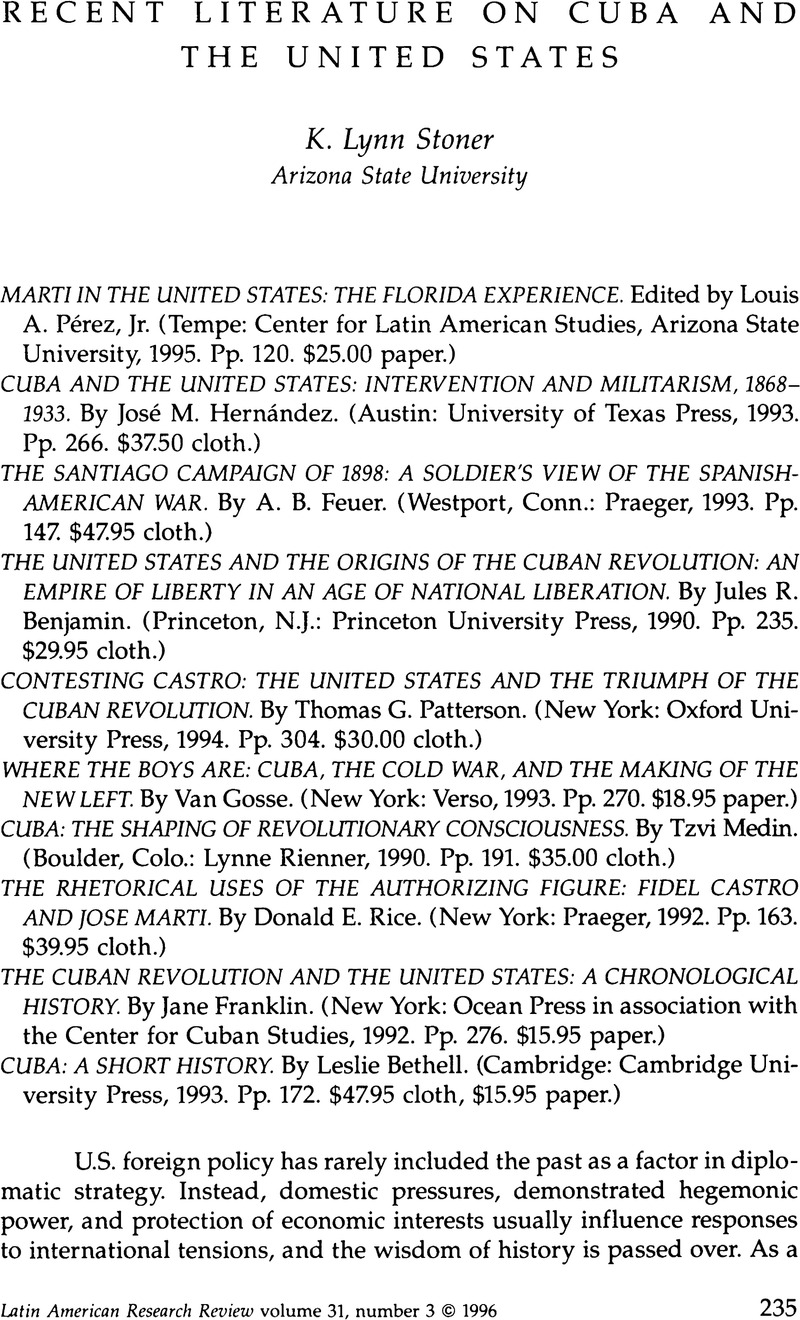

Recent Literature on Cuba and the United States

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1996 by the University of Texas Press

References

1. The Resolutions of Tampa laid out the objectives of the final war of independence. Cubans were to fight for liberation from Spain, racial and social justice, resistance to U.S. expansionism, democracy, workers' rights, and modern government. The Principles of the Revolution organized the Partido Revolucionario de Cuba, stating the requirements for membership, the preeminence of the party over other organizations until independence was won, leadership positions, and the means to ending Spanish colonial rule in Cuba.

2. John Kirk, José Martí: Mentor of the Cuban Nation (Tampa: University Presses of Florida, 1983); Jorge Mañach, Martí, Apostle of Freedom, translated by Coley Taylor (New York: Devin-Adair, 1950); Philip Foner, Our America (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977); Enrico Santí, José Martí and the Cuban Revolution Retraced (Los Angeles: Latin American Center, University of California, Los Angeles, 1986); Louis A. Pérez, Jr., Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); and Carlos Ripoll, José Martí, the United States, and the Marxist Interpretation of Cuban History (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction, 1984).

3. Gerald Poyo, “With All, and for the Good of All”: The Emergence of Popular Nationalism in the Cuban Communities of the United States, 1848–1898 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1989).

4. Louis A. Pérez, Jr., Lords of the Mountains: Banditry and Peasant Protest in Cuba, 1898–1918 (Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989); and Rosalie Schwartz, Lawless Liberators: Political Banditry and Cuban Independence (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1989). Their differing analyses of lawlessness are detailed in two book reviews: by Catherine LeGrand, American Historical Review 96, no. 2 (Apr. 1991):644; and by Robert L. Paquette, American Historical Review 70, no. 1 (Feb. 1990):188.

5. Aline Helg, “The Afro-Cuban Protest: The Partido Independiente de Color, 1908–1912,” Cuban Studies/Estudios Cubanos 21 (1991):101–21.

6. Books that have seriously treated the topic of Castro's rise to power following Batista's flight are Samuel Farber, Revolution and Reaction in Cuba, 1933–1960: A Political Sociology from Machado to Castro (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1976); Tad Szulc, Fidel: A Critical Portrait (New York: Morrow, 1986); Robert E. Quirk, Fidel Castro (New York: Norton, 1993); Jorge Domínguez, Cuba: Order and Revolution (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard, 1978); Cuba, edited by Jorge Domínguez (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1982); U.S.-Cuban Relations in the 1990s, edited by Jorge Domínguez and Rafael Hernández (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1989); and Marifeli Pérez-Stable, The Cuban Revolution: Origins, Course, and Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

7. Fredrick Pike, The United States and Latin America: Myths and Stereotypes of Civilization and Nature (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992).

8. See Quirk, Fidel Castro.