Authoritarian candidates have gained a foothold across several American, European, and Latin American party systems. Brazil’s 2018 presidential election brought the far right to power and marked the most dramatic shift in the country’s history of presidential elections. Embracing authoritarian inclinations and political intolerance while showing an open disregard for democracy and democratic institutions, Jair Bolsonaro took control of the Brazilian national executive (Ciccariello-Maher Reference Ciccariello-Maher2020).

The success of a far-right authoritarian candidate in Brazil has been attributed to numerous socioeconomic and political crises, including the country’s long-term economic distress, political parties’ corruption, and the legitimacy crisis of political institutions (Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2019; Guachalla et al. Reference Guachalla, Ximena, Hummel, Handlin and Smith2021). Other explanations have focused on institutional features such as multilevel electoral coordination and the fractured Brazilian party system (Ribeiro and Borges Reference Ribeiro and Borges2020; Borges Reference Borges2021). In terms of public opinion, scholars have argued that Bolsonaro’s success indicated resentment toward past governments of the Worker’s Party (PT), new issue cleavages, and possibly ideological sorting in the electorate (e.g., Amaral Reference Amaral2020; Layton et al. Reference Layton, Amy Erica Smith and Cohen2021; Rennó Reference Rennó2020). However, these explanations have been largely unrelated to Bolsonaro’s authoritarian appeals.

Here, I put forward evidence using Brazilian voters’ inclination toward authoritarianism to explain the rise of rightist leaders. Increasing evidence demonstrates that voters’ authoritarianism provides support for right-wing and anti-democratic candidates worldwide (Cohen and Smith Reference Cohen and Erica Smith2016; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2018; Feldman Reference Feldman, Eugene Borgida and Miller2020). Authoritarianism is conceptualized as a social psychological orientation that prefers beliefs and values social conformity over individual autonomy in society (Feldman Reference Feldman2003). The preference for conformity over autonomy indicates hierarchical views of authority that often manifest in the political context (e.g., Stenner Reference Stenner2005; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009).

Using the AmericasBarometer 2019 national survey data, I measure authoritarian orientation on a continuum using an individual’s preference for desirable qualities in children. Findings indicate that the effect of voters’ authoritarian orientations on voting for Bolsonaro are as influential as partisanship, right-wing ideology, religion, or negative feelings toward the PT. Although these other variables are also relevant to Bolsonaro’s victory, my results suggest that his candidacy was uniquely able to mobilize a coalition of authoritarian voters. Bolsonaro did not have to convince authoritarian voters of his political positions. Instead, he told such voters what they wanted to hear regarding a range of political issues and aligned his message with their societal worldviews.

Authoritarianism: Enforcing social conformity

Scholarly conceptions of authoritarianism—as a psychological variable rather than a feature of political systems—have evolved significantly over time. Political psychologists have offered several theoretical alternatives to the original psychoanalytic framework as well as more valid scales with which to measure it (e.g., Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik and Sanford1950; Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1988, Reference Altemeyer1996; Duckitt Reference Duckitt1994; Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Stenner Reference Stenner2005; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009). Although scholars have debated the origins, conceptualizations, and measurement of authoritarianism, since the publication of “The Authoritarian Personality” (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik and Sanford1950) scholars have recognized that the authoritarian orientation is related to child-rearing practices.

As Feldman and Stenner (Reference Feldman and Stenner1997, 747) explain, “how to ‘bring up’ or socialize children is a matter of profound consequences, involving basic human values and objectives.” According to Feldman’s (Reference Feldman2003) social conformity account, an authoritarian orientation is evident in attitudes toward power and worldviews of society, in particular how people resolve the fundamental tension between personal autonomy and social conformity. For authoritarians, social cohesion and conformity to in-group norms and values are preferable over personal freedom and individual autonomy. It is critical for them that citizens respect and obey traditional social norms and rules.

As Feldman (Reference Feldman2003, 55) observes, “people … who desire social conformity should want children to be taught to be good, obedient citizens. Conversely, those who value autonomy should want to encourage it in their children.” Therefore authoritarians believe that it is best for children to be obedient, not challenge authority, and accept the way society is. A conformist orientation includes an unwillingness to permit others to step out of narrowly defined limits of what is proper and acceptable. Thus a conformist orientation implies not only intolerance of deviant social and political beliefs but also intolerance of any belief thought to be threatening to the social order. Accordingly, the opposing nature of these normative views leads those at the opposite ends of the authoritarian continuum to display different political attitudes and behavior (Feldman Reference Feldman, Eugene Borgida and Miller2020).

The core reason that preferences differ across the authoritarianism continuum is that the more authoritarian tend to perceive threat in social change and challenges to social cohesion, while those who are less authoritarian tend not to (Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Van Assche, Dhont, and Pettigrew Reference Van Assche, Dhont and Pettigrew2019). For example, authoritarians are more likely than nonauthoritarians to reject policies favorable to new immigration into European societies (Claassen and McLaren Reference Claassen and McLaren2019). Such aversion to differences extends to racial and ethnic groups as well: authoritarian attitudes are strongly predictive of negative racial stereotypes (Duckitt Reference Duckitt1992; Feldman and Stenner Reference Feldman and Stenner1997). Moreover, there is evidence that authoritarians display more negative attitudes with regard to LGBTQ rights than their nonauthoritarian peers (Barker and Tinnick Reference Barker and Tinnick2006; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009).

Apart from an inclination toward moral, ethnic, and political intolerance, authoritarians tend to favor social restrictions on behavior and civil liberties and are willing to sacrifice liberty for order (Feldman and Stenner Reference Feldman and Stenner1997). Authoritarians are much more likely to support the use of force and punitive responses, including corporal punishment, and in some cases even support the death penalty for those who deviate from certain social norms (Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005). The current literature on authoritarianism illustrates strong correlations between these categories of attitudes and authoritarian orientations (Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2018).

Within the electoral realm, a preference for social control over personal autonomy often manifests as support for authoritarian candidates viewed as powerful and forceful due to their propensity for suppressing nonconformity (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1981; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009). It also correlates strongly with parties and candidates who promote these issues, which explains voting for both Donald Trump in 2016 (Weber, Federico, and Feldman Reference Weber, Federico and Feldman2017) and for far-right parties in Europe (Vasilopoulos and Lachat Reference Vasilopoulos and Lachat2018). At the same time, studies have shown that the political influence of authoritarianism is contingent on the context of elections (Cizmar et al. Reference Cizmar, Layman, McTague, Pearson-Merkowitz and Spivey2014; Knuckey and Hassan Reference Knuckey and Hassan2020).

Changes in political context can connect authoritarianism to—or disconnect it from—politics (Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Stenner Reference Stenner2005; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Moseley, Layton and Cohen2021). Authoritarian leaders appeal to more voters in times of social change and political crisis than in times of relative stability (Finchelstein Reference Finchelstein2019). In these situations, voters may prefer a leader with the requisite characteristics and skills to resolve the crisis (Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009). Those higher in latent authoritarianism are especially likely to endorse strongman tactics when their favored leaders argue these tactics are necessary to confront bad actors (Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2018). Other authors show that authoritarian leaders not only arise out of preexisting societal crises but also act out and even propagate crises (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016).

Child-rearing values and authoritarianism

Measuring authoritarianism at the mass public opinion level, rather than as a feature of political systems, has been controversial. Feldman and Stenner (Reference Feldman and Stenner1997) provide a useful history of these measurement problems with regard to the original measure, the F-scale (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik and Sanford1950), and its alternative, the right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) scale (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1981). The F-scale has been criticized by researchers for its psychometric weaknesses. The main problem with F-scale-type measurements is the inclusion of items that are conceptually similar to the consequences of authoritarianism that scholars seek to explain (e.g., prejudice and intolerance).

The RWA scale suffers from more serious problems because it contains questions with explicitly political content. Feldman (Reference Feldman2003, 44–45) describes these issues, noting that sometimes “scale items look like measures of social conservatism, not authoritarianism,” and that at their worst, the scale items come “uncomfortably close to the variables we want to predict.”Footnote 1 The focus of the F-scale and RWA scale on social threat and authoritarian rhetoric primes authoritarian responses in individuals, which results in survey measurement bias and renders such tools unreliable in the evaluation of authoritarianism.

Measurement of this concept improved greatly when Stanley Feldman and Karen Stenner (Reference Feldman and Stenner1997) empirically demonstrated that a person’s views on socialization and child-rearing values are useful indicators of one’s authoritarian orientations. The child-rearing scale is based on a series of forced-choice questions asking respondents about the preferable values children should possess. The scale arranges respondents’ preferences on a continuum: at one end are people who believe that children should be well-behaved, obedient, and respectful of elders; at the other end are people who believe that children should be independent, responsible, and curious (Feldman and Stenner Reference Feldman and Stenner1997, 747).

Qualities such as obedience, respect for elders, and good behavior in children suggest a hierarchical understanding of authority in a family, which, in turn, should reflect a similar understanding about political authority (Feldman Reference Feldman, Eugene Borgida and Miller2020). As a result, authoritarian orientations are anchored between two poles: one emphasizing individual autonomy, freedom, and social change; the other emphasizing social conformity, obedience, and respect for social order. An individual’s position on this continuum is determined by the degree to which they endorse personal autonomy versus strict conformity to societal norms (Feldman Reference Feldman2003, 48).

The child-rearing measurement is chosen because of its exogeneity to a wide range of political attitudes, temporal stability, and ability to measure authoritarian political thinking (see Engelhardt, Feldman, and Hetherington Reference Engelhardt, Feldman and Hetherington2021). Efficiently measuring this dimension depends on making people choose one of each value pair (Engelhardt, Feldman, and Hetherington Reference Engelhardt, Feldman and Hetherington2021, 4). The value pairs in the child-rearing measure are not antonyms; rather, they make respondents choose between often competing goals. Thus individuals with authoritarian orientations would be willing to choose social conformity over individual autonomy. The parental values scale allows us to distinguish authoritarian predispositions from authoritarian products (e.g., attitudes and evaluations; Stenner Reference Stenner2005, 24).

Authoritarianism (as expressed in child-rearing values) features prominently in explanations of voters’ moral, political, and racial intolerance in the West (e.g., Duckitt Reference Duckitt1994; Stenner Reference Stenner2005; Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009; Johnston, Newman, and Velez Reference Johnston, Newman and Velez2015). More important, across a wide variety of countries and contexts, politics has evolved such that issues structured by authoritarianism are increasingly central to party contestation (Engelhardt, Feldman, and Hetherington Reference Engelhardt, Feldman and Hetherington2021). The concept of authoritarianism is theorized in universal terms (Feldman Reference Feldman, Eugene Borgida and Miller2020); hence, if the results across dependent variables in comparative context are consistent, this work will provide not only construct validity but also substantial cross-country validity for the child-rearing scale.

In Latin America, the same measurement strategy was employed by Cohen and Smith (Reference Cohen and Erica Smith2016, 3). The authors validate the authoritarianism scale by showing that the scale is associated with theoretically relevant personal attributes, including political intolerance and support for media censorship.Footnote 2 Controlling for common demographics and ideology, I validate the child-rearing scale in Brazil by showing that this nonpolitical scale has the expected relationships with relevant issue areas, which include views about sexuality, religious and political attitudes, and the propriety of leadership tactics deemed by supporters as necessary to maintain social cohesion and conformity.

Data and measures

The AmericasBarometer, which is part of the Latin American Public Opinion Project, is a periodic study of thirty-four countries in the western hemisphere using nationally representative samples from each country. The Brazilian sample included 1,498 voting-age adults who completed face-to-face interviews conducted in Portuguese in February 2019. The sample is representative of voting-age Brazilian regional populations. As reported in the AmericasBarometer technical report, men represent 49.9 percent of the overall sample and women, 50.1 percent. Half of the respondents in the AmericasBarometer were presented with three pairs of qualities and asked to indicate which of each pair is most desirable for a child to hold: (1) independence or respect for the elderly; (2) obedience or autonomy; and (3) creativity or discipline.

Participants’ responses were then quantified, with each “authoritarian” response to a pair of qualities (respect for the elderly, obedience, discipline) receiving a score of 1 and each “nonauthoritarian” response (independence, autonomy, creativity) receiving a score of 0. The composite measure is an additive scale of the three items ranging from zero to three. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the authoritarianism scale.

Table 1. Authoritarianism in Brazil measured via attitudes toward child-rearing practices.

Note: Authoritarianism scale ranges from 0 (nonauthoritarian) to 3 (strong authoritarian).

Standard errors are presented in parentheses. Cronbach’s alpha = .51

As table 1 illustrates, the majority of respondents indicated that the most important qualities for children to have are obedience, discipline, and respect for the elderly. Considering only this pattern, it seems reasonable to characterize Brazil’s population as a “pro-authoritarian mass public” (Seligson and Tucker Reference Seligson and Tucker2005, 13). However, a more thorough inspection of the individual differences (table A4, Appendix A) among authoritarian attitudes in Brazil reveals similarities with those found within the United States and in large cross-national studies (e.g., World Values Survey): nonwhites, conservatives, the less educated, and women tend to score higher on the scale (Brandt and Henry Reference Brandt and Henry2012; Henry Reference Henry2011; Duckitt Reference Duckitt1992; Pérez and Hetherington Reference Pérez and Hetherington2014).

With regard to reliability, the Cronbach’s alpha of .51 is within a similar range of values as that reported in other large surveys, including surveys conducted in Latin America. For example, Knuckey and Hassan (Reference Knuckey and Hassan2020, 4) report Cronbach’s alphas between .58 and .65 in American National Election Studies from 1992 to 2016, whereas Cohen and Smith (Reference Cohen and Erica Smith2016, 3) report alphas between .19 and .56 in Latin America. The use of only three indicators contributes to a relatively lower scale reliability, which in turn attenuates correlation or regression coefficients estimating the strength of a relationship between authoritarianism and dependent variables (Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and James2008).

Results

The AmericasBarometer survey uses a broad range of attitude questions that represent an array of contemporary social and political preferences as well as attitudes toward the use of force.Footnote 3 I employ these multiple dependent variables to establish the validity of the child-rearing scale as a measure of authoritarianism in the Brazilian context. The measurement of social and political attitudes are all continuous indices based on respondents’ positions on multiple-point scales, thus ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models are used here. Additionally, I rescaled all variables to range from 0 to 1, with the exception of the variables “owning a gun” and “death penalty” (e.g., discrete binary answers such as support or oppose).

Figure 1 plots the marginal effects of authoritarianism on attitudes toward the use of force. In the OLS models, the marginal effects indicate the change in the predicted mean values of the attitudinal variable with respect to the level of authoritarianism. In nonlinear regression models, the marginal effects signify how the predicted probabilities in the attitudinal dependent variable change (e.g., support or oppose) when the authoritarianism variable (independent variable) changes. The regression models and estimates for each dependent variable are shown in table A1 in the appendix.

Figure 1. Marginal effects of authoritarianism on attitudes toward the use of force.

Previous studies have found a strong connection between authoritarianism and feelings about security and threats (Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009). Gun ownership tends to be viewed by authoritarians as a means to provide protection for oneself (Lizotte Reference Lizotte2019). For example, Bolsonaro favors relaxing regulations on gun control and allowing citizens to own and carry guns for defense (Rennó Reference Rennó2020, 7). Accordingly, authoritarians are significantly more likely than nonauthoritarians to own a gun if legally able to (A, p < .001).

Another central aspect of authoritarianism is the willingness to employ extreme measures to punish those who violate laws. Authoritarianism has a strong effect on a person’s disposition toward punishments (Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Stack Reference Stack2003). Krause (Reference Krause2020) provides evidence that authoritarian citizens in Latin America support policies and crime control measures that violate the rights of criminal suspects and other marginalized groups. Accordingly, results show that authoritarians are significantly more likely to support the most extreme use of legitimate force, namely the death penalty (B, p < .01). Capital punishment is a long unused form of punishment in Brazil. However, Jair Bolsonaro openly supports the revival of capital punishment for violent crimes and life imprisonment. In the US context, authoritarianism predicts support for increased defense spending, the use of military force over diplomacy to solve international crises, and trust in the armed forces (Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005). I find the same relationship hold in Brazil, as authoritarians are significantly more likely to support the armed forces (C, p < .05).

These results fit previous descriptions of authoritarians (e.g., Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996; Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Funke Reference Funke2005) and are consistent with those found among Trump’s supporters in the 2016 US elections (Womick et al. Reference Womick, Tobias Rothmund, King and Jost2018). Therefore, there are correlations between the way in which authoritarians attach importance to their own safety and security and their support of gun ownership, the armed forces, and harsh punishments for those viewed as deviants with respect to social order stability (Funke Reference Funke2005).

Originally, the concept of authoritarianism was developed to explain an individual’s adherence to antidemocratic, totalitarian, and intolerant ideologies (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik and Sanford1950). The willingness to support authoritarian arrangements tends to be positively associated with authoritarian orientations (Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Seligson and Tucker Reference Seligson and Tucker2005).Footnote 4 Accordingly, the term “democratic character” includes preferences for democracy as a form of government as well as tolerance toward people holding different worldviews (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1988; Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982; Feldman Reference Feldman, Eugene Borgida and Miller2020).

Figure 2 illustrates how authoritarianism involves consistent negative relationships across political attitude variables. As expected, authoritarian voters are more likely to display a disaffection with current political systems and parties. Moreover, authoritarian orientations are positively associated with intolerance of the political rights of groups with which the individual expresses strong disagreement. Those individuals who score high in authoritarianism tend to oppose the rights of the main established parties to compete in elections, compared to nonauthoritarians (D, p < .05). Such individuals also tend to be more dissatisfied with and less supportive of democracy (E, p < .05) and to exhibit lower political tolerance (F, p < .01).

Figure 2. Marginal effects of authoritarianism on political attitudes.

Last, figure 3 plots the marginal effects of authoritarianism on social attitudes. Feldman’s (Reference Feldman2003) theory implies that strong supporters of authoritarianism are more likely to hold prejudicial and intolerant attitudes. Authoritarians tend to be social conformists and expect others to conform to the established social norms of sexuality (Barker and Tinnick Reference Barker and Tinnick2006). Results show that authoritarians are less supportive of the rights of those identifying as gay or lesbian to marry and to run for political office (G, p < .001). Because gay and lesbian individuals fail to conform to existing social conventions regarding sexual behavior, authoritarians are inclined to dislike such individuals and be less supportive of a range of gay rights initiatives (Barker and Tinnick Reference Barker and Tinnick2006; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009, 96).

Figure 3. Marginal effects of authoritarianism on social attitudes.

Furthermore, authoritarians tend to be more religious and view religion as a very important aspect of their life (H, p < .001). The relationship between religiosity and authoritarianism was first documented by Adorno and others in the 1950s, and subsequent research has further established the existence of such a correlation (see Burge Reference Burge2018; and Feldman and Johnston Reference Feldman and Johnston2014). The strength and significance of these findings have prompted additional researchers to examine the cognitive mechanisms underlying this relationship; this research identifies an important role for low openness to experience and high rigidity in the processing of information (Wink, Dillon, and Prettyman Reference Wink, Dillon and Prettyman2007).

Authoritarians are also more likely than nonauthoritarians to disapprove of those participating in peaceful demonstrations to express their views (I, p < .01). Collective demonstrations are more often seen by authoritarians as nonconforming and disruptive to the established social order (Feldman Reference Feldman2003). Indeed, authoritarians’ fear of public disorder and social disturbance is so pervasive that it often results in support for a strong government response to such demonstrations against a cause of concern (Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009).

By and large, authoritarianism is consistently associated with a range of conservative social and political attitudes as well as attitudes toward the use of force (with p values ranging from .001 to .05, table A1, Appendix A). The political attitudes and beliefs among authoritarians versus nonauthoritarians are expected to diverge even further as more controversial social and political issues grow increasingly important and salient within the Brazilian political arena.

Most important, the above results support the utility of the child-rearing scale as a reliable and valid measure within the Brazilian context that provides cross-country robustness to the measurement of authoritarian orientations in Latin America and acts as an indicator of social and political values as theorized by Feldman’s (Reference Feldman2003) social conformity account.

Presidential voting model, 2018

The AmericasBarometer survey inquired about a participant’s first round 2018 vote choice only. Given the nominal nature of vote choice in multiparty systems, a multinomial regression is the most appropriate model specification for investigating vote choice (Alvarez and Nagler Reference Michael and Nagler1998). The vote-choice variable was divided into three categories: votes for challenger Jair Bolsonaro of the right-wing Social Liberal Party (the reference category), votes for the PT incumbent Fernando Haddad, and votes for other candidates. Blank and null votes were excluded from the analysis.Footnote 5 I include standard demographic variables in the voting model as well as terms for geographic regions (the Southeast region being the reference category) and political behavior variables: partisanship, ideology, religious denomination (evangelicals), and economic voting.Footnote 6 In addition, I include each of the social and political preferences and attitudes toward the use of force variables individually.

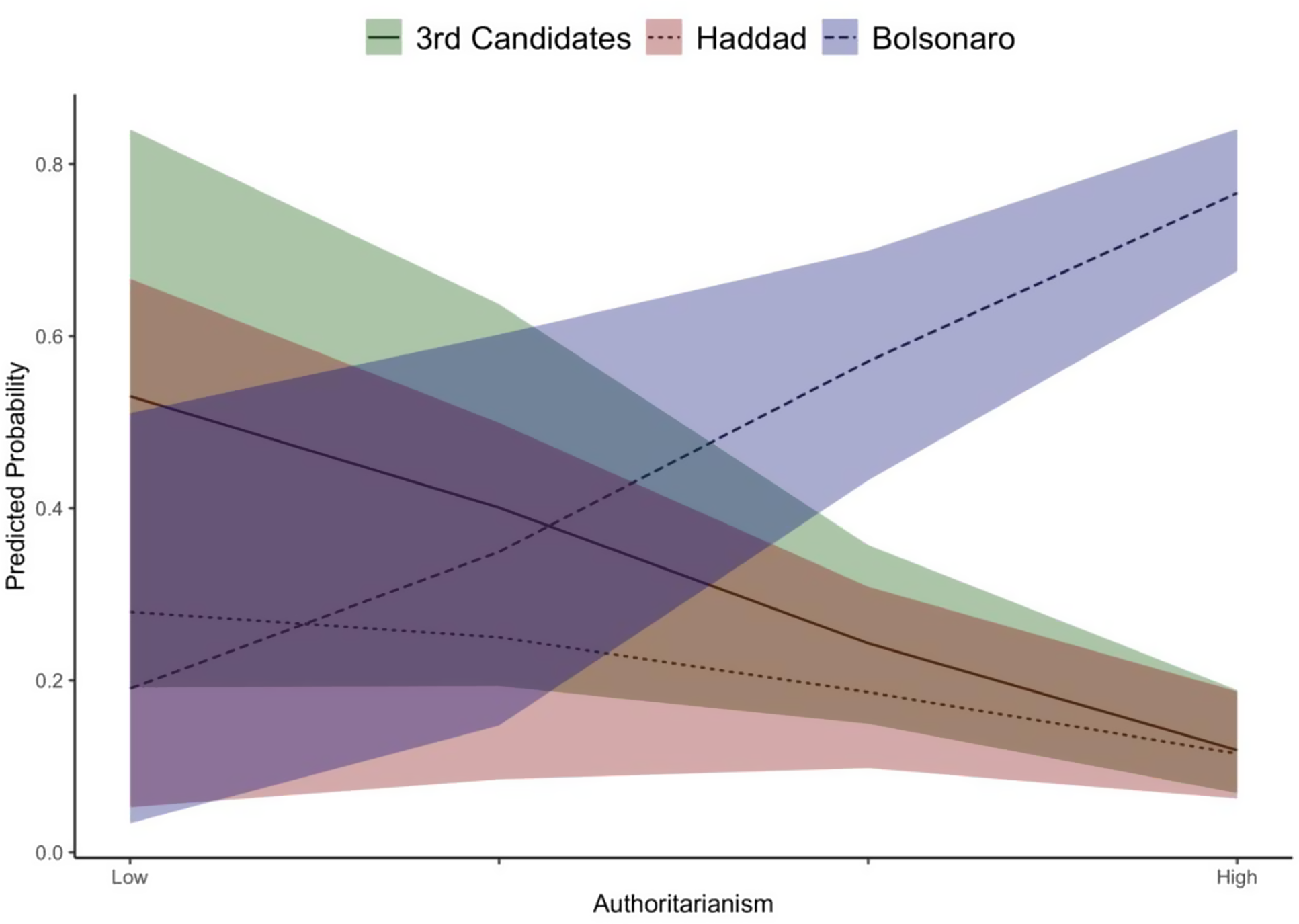

In figure 4, I present the graphical representation of the impact that a unit of change from low authoritarianism to high authoritarianism has on the estimated probability of casting a vote for Haddad, Bolsonaro, or a third-party candidate, holding all other variables constant at their observed values. When the predicted probabilities are arrayed across the authoritarian scale, the highest probability that an individual votes for Bolsonaro occurs at the highest end of the authoritarian continuum. Among those ranked low in authoritarianism, the probability of voting for third-party candidates is indistinguishable from the probability of voting for Haddad. It is important to note that authoritarianism is only positively associated and significant for Jair Bolsonaro.

Figure 4. Authoritarianism predicted probabilities on 2018 presidential voting in Brazil.

Authoritarianism exerts a positive and significant effect on the probability of voting for Bolsonaro in comparison to voting for either Haddad or a third-party candidate (p < .05). In these elections, the absolute majority of high-authoritarian voters chose Bolsonaro, whereas nonauthoritarian voters supported other candidates. Notably, these results hold even after controlling for ideology, religiosity, partisanship, issue positions, and antipetismo (i.e., anti–Worker’s Party sentiments). Table 2 presents the coefficients for the 2018 multinomial voting model.

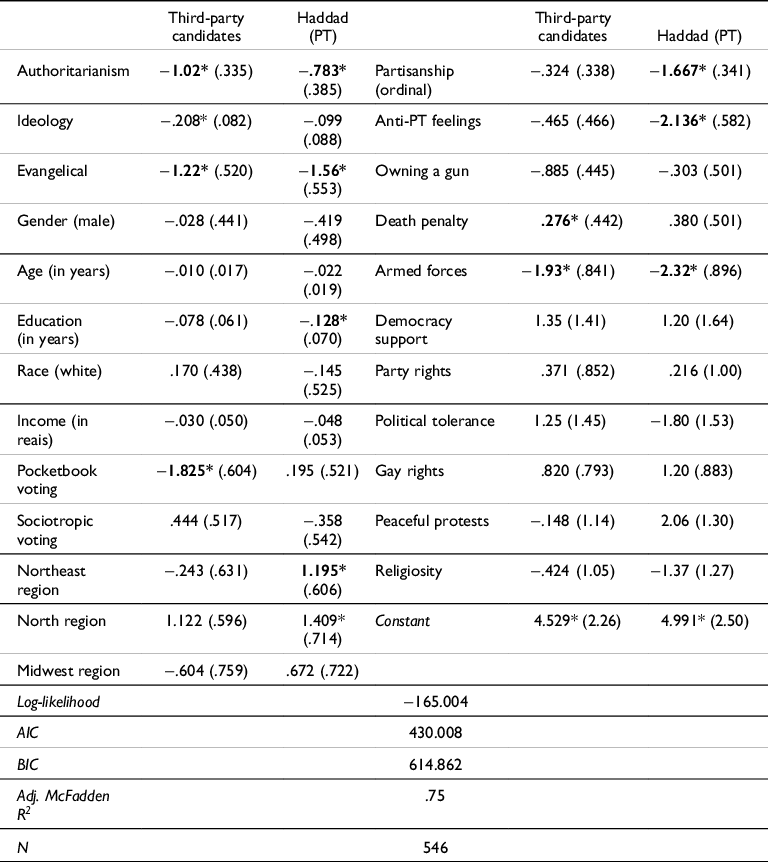

Table 2. Multinomial logistic regression for the 2018 Brazilian presidential vote.

Note: Jair Bolsonaro is the reference category. Standard errors are presented in parentheses.

*p < .05.

Voters from the Northeast and Northern regions of Brazil were significantly more likely to vote for Fernando Haddad than for Jair Bolsonaro (p < .05). In fact, a geopolitical division within the country has existed since at least 2014, with vast areas of the Northeast and Northern regions casting more votes for the Worker’s Party, and antipetista voters mostly concentrated in the Midwest and Southeast regions (Ribeiro, Carreirão, and Borba Reference Ribeiro, Carreirão and Borba2016).

While many Brazilians voters agree with Bolsonaro’s conservative political positions, most of the issue positions included in this study did not play a significant role in vote choice. As table 2 shows, only support for the armed forces was significantly predictive of casting a vote for Bolsonaro over the other candidates (p < .05), and support for the death penalty increased the probability that an individual votes for Bolsonaro (p < .05) only in comparison to third-party candidates.Footnote 7

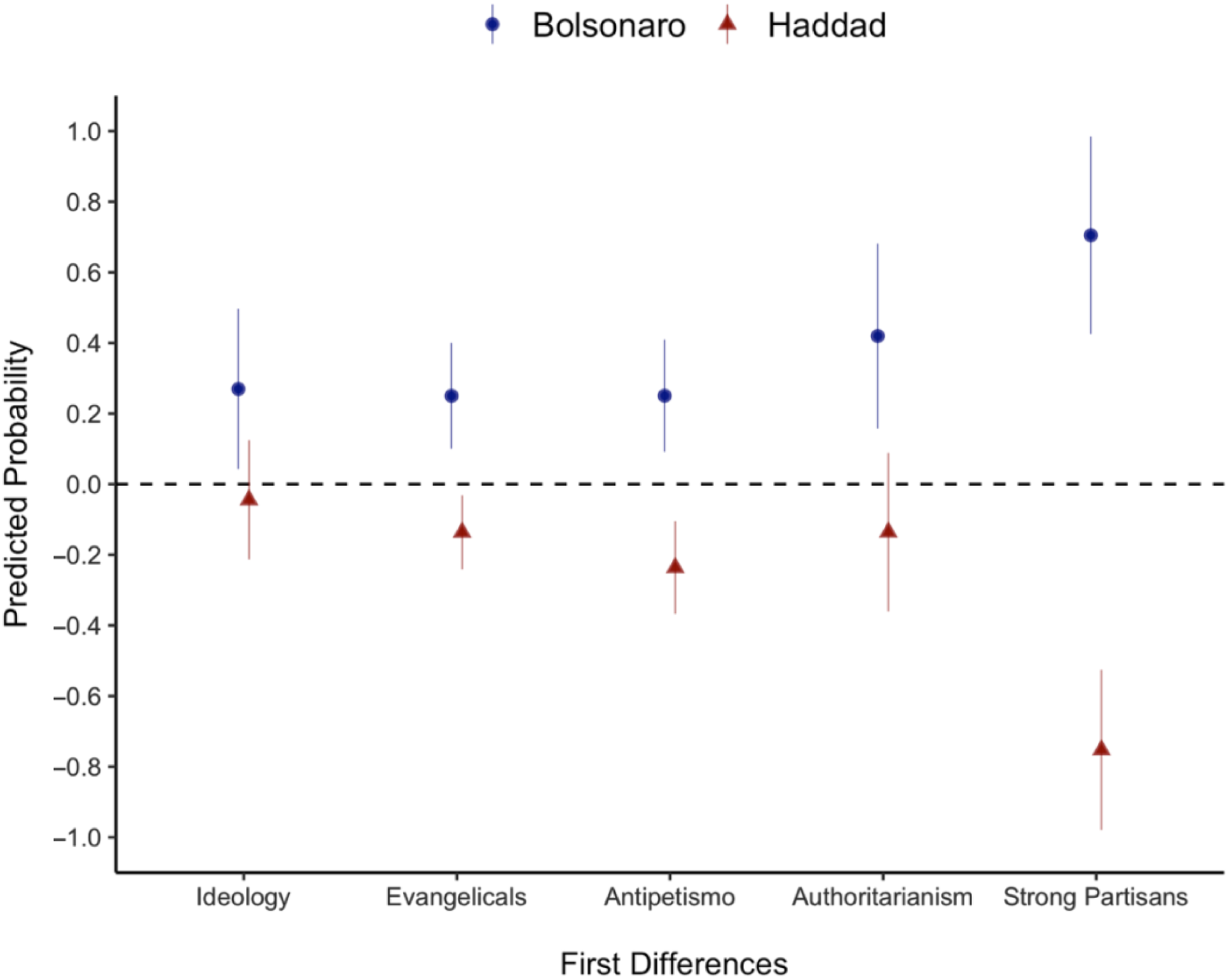

To provide a substantive interpretation of the effect of authoritarianism on voting for Bolsonaro in comparison with the other relevant and statistically significant political behavior variables, I estimate the quantities of interest to fully extract the information available from these statistical models (King, Tomz, and Wittenberg Reference King, Tomz and Wittenberg2000). In figure 5, I present the first differences in predicted probabilities of voting for Jair Bolsonaro and Fernando Haddad, the two candidates who received enough votes to continue running in the second-round runoff election.

Figure 5. First differences in predicted probabilities of voting for Bolsonaro and Haddad.

Each point in figure 5 represents the change in predicted probabilities of voting for Bolsonaro or Haddad when changing from the lowest observed value to the highest observed value of each statistically significant variable, with all other independent variables held at their mean or mode values, along with 95 percent confidence intervals (CI).Footnote 8 Most studies on voting behavior in Brazil have concluded that the left-right scale is poorly associated with vote choice or political preferences (Ames and Smith Reference Ames and Erica Smith2010; Oliveira and Turgeon Reference Oliveira and Turgeon2015; Batista Pereira Reference Batista Pereira2020). However, 2018 Brazilian voting behavior data reveal that an individual’s ideology is significantly associated with voting for Bolsonaro (p < .05) in comparison to third-party candidates. The change of moving from extreme left-wing to extreme right-wing ideology in the probability of voting for Bolsonaro is +27.5% CI [5.7%, 49.8%], despite the lack of significant effects on the probability of voting for Haddad or other candidate.

Evangelicals were also significantly more likely to vote for Bolsonaro and less likely to vote for Haddad or for a third-party candidate (p < .05). Thus religion has once again become a potent political force in Brazilian elections. Evangelicals display distinct electoral behavior when compared to other voters in past elections (Smith Reference Smith2019). For example, past presidential candidates Anthony Garotinho and Marina Silva received a great deal of support from this voting bloc in 2002 and 2006, respectively (Borges and Vidigal Reference Borges and Vidigal2018).

In the 2018 elections, however, evangelicals became even more politically relevant (Finchelstein Reference Finchelstein2019) as Bolsonaro received strong support from evangelical sectors and churches in Brazil (Smith Reference Smith2019; Amaral Reference Amaral2020). The first difference between a nonevangelical and an evangelical voter shows an increase of +25% CI [10.1%, 38.5%] on the vote for Bolsonaro while reducing by −13.5% CI [−23.9%, −3.7%] the probability of voting for Haddad.

In the Brazilian context, partisanship has typically centered on the Worker’s Party because it is the political party most associated with both party preference and rejection (Samuels and Zucco Reference Samuels and Zucco2018). Despite the limited effects of antipetismo on political attitudes (Ribeiro, Carreirão, and Borba Reference Ribeiro, Carreirão and Borba2016; Borges and Vidigal Reference Borges and Vidigal2018), the increase of negative partisans in Brazil implies that any PT challenger presidential candidate benefits politically from the proliferation of such an ideology. Accordingly, negative feelings toward the PT lead to a significant increase in the vote probability for Bolsonaro in comparison to Haddad (p < .05), whereas no significant differences arise between third-party candidates. Strong negative feelings toward the PT (antipetismo) result in a significant increase of +25% CI [8.9%, 42.1%] in the probability that an individual votes for Bolsonaro, whereas the probability of an antipetista voter choosing Haddad is −23.7% CI [−40.1%, −10.1%].

The partisanship measurement, with respect to the intensity of partisan feelings toward the PT and PSDB, is statistically significant (p < .05) and remains one of the strongest voting predictors in Brazil. The difference in the ordinal scale between a strong PT partisan and a strong PSDB partisan in voting for Bolsonaro is an impressive +69.9% CI [36.4%, 90.2%]. This means that PT partisans are extremely more likely to vote for their party’s candidate, while PSDB partisans are more likely to vote for the challenger (Bolsonaro). These robust results confirm the strength of party feelings in voting behavior in Brazil (Borges and Vidigal Reference Borges and Vidigal2018; Samuels and Zucco Reference Samuels and Zucco2018). As Samuels and Zucco (Reference Samuels and Zucco2018, 80) highlight, voting behavior in Brazil has been largely structured by the partisan attitudes of the PT and PSDB. Strong partisans tend to be the most attentive to political campaigns, the most informed about politics, and the most likely to follow party cues and have the strongest opinions of and reactions to the political world (Bartels Reference Bartels2002; Zaller Reference Zaller1992).

Ultimately, the difference between nonauthoritarian and authoritarian voters with respect to the probability of voting for Bolsonaro is +41.9% CI [14.9%, 64.5%], without significant effects on the vote probability for Haddad. The effects of authoritarian tendencies between political-social change versus political-social stability preferences are as powerful as partisanship, ideology, religion, or even antipetismo (figure 5). Under certain political and electoral conditions, right-wing authoritarian candidates successfully mobilize the electoral support of authoritarian voters and win the presidential vote in established democracies.

Discussion

The election of Jair Bolsonaro in 2018 ended the long runoff history between the PT and the PSDB. This work advances the field’s understanding of Bolsonaro’s political success beyond the previously established findings around antipetismo, religious cleavages, or anti-corruption feelings. By applying a social psychological orientation measured by beliefs about social conformity and individual autonomy in child-rearing values, I provide strong evidence that authoritarianism is important for explanations of beliefs about the use of force in Brazil.

Moreover, this work demonstrates that assessing authoritarianism using child-rearing questions is strongly associated with a wide range of political attitudes and social preferences from intolerance attitudes to support for democracy, women’s equality, or LGBTQ rights, as a valid measure of authoritarianism should be. Most critically, the results reveal that authoritarianism is associated with electoral support for an openly authoritarian right-wing politician in the largest Latin American democracy.

The significant impact of ideology on the vote probability for Bolsonaro in Brazil is another important finding. Brazil has been experiencing severe fragmentation in its party system configuration together with the emergence of new right-wing actors and organizations in recent years (Zucco and Power Reference Zucco and Power2020). Using data from the 2018 Brazilian Election Panel Study, Rennó (Reference Rennó2020, 5) argues that the Bolsonaro vote was oriented on an alignment of right-wing ideological positions. Likewise, using data from the 2018 Brazilian Election Study, Amaral (Reference Amaral2020) finds significant associations between ideology and voting behavior with an increase from 27% in 2014 to 43% in 2018 (Amaral Reference Amaral2020, 8). Taken together with the increase in the number of individuals reporting a right-wing ideology, these findings raise several questions about voters’ ideological positions. Is voters’ ideological self-placement changing? Or is the symbolic meaning of left and right labels changing among Brazilian voters?

Dinas and Northmore-Ball (Reference Dinas and Northmore-Ball2020) state that an individual’s willingness to classify themselves as left-wing or right-wing is shaped by a general reluctance to identify with the ideological label associated with a past authoritarian regime (called anti-dictator bias).Footnote 9 In Brazil, the past association between the authoritarian military regime and the right (e.g., Alvarez et al. Reference Alvarez, Antonio Cheibub, Limongi and Przeworski1996; Power Reference Power, Loxton and Mainwaring2018) is reflected in the reluctance of Brazilian political elites to accept the label “right-wing,” a tendency known in Brazil as “ashamed right” (Dinas and Northmore-Ball Reference Dinas and Northmore-Ball2020; Power and Zucco Reference Power and Zucco2009). However, as an openly far-right politician with a comprehensive right-wing agenda and rhetoric, Jair Bolsonaro represents the antithesis of this tendency (Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2019, 75; Rennó Reference Rennó2020).

Presidential elections are information-rich environments, and citizens rely heavily on political elites to gather information about politics (Zaller Reference Zaller1992; Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2006; Zechmeister Reference Zechmeister, Ryan, Matthew and Elizabeth2015). Once informed, authoritarian individuals in Brazil likely connected their worldviews as well as their religious and social experiences with Bolsonaro’s positions on political-social issues and adopted those issue positions as their own (Bartels Reference Bartels2002; Lenz Reference Lenz2009). Put a different way, Bolsonaro provided the ideological packaging necessary for certain voters to understand their own belief system structure (Zechmeister Reference Zechmeister2006) or provided the social-identity cue for voters to recognize themselves as being politically right-wing (Hillygus and Shields Reference Sunshine and Shields2008; Lupu Reference Lupu2013). As a result, when asked to place themselves within the left or right spectrum, more individuals might express a self-reported symbolic ideology in opinion polls. More research is needed to investigate these patterns in ideological self-placement and the public opinion connotations of ideological labels in Brazil.

In past presidential elections, authoritarian voters in Brazil likely supported any PT challenger candidate due to the lack of an authoritarian alternative more aligned with their preferences. In the 2018 election, Bolsonaro offered an authoritarian voting option, and his candidacy gained traction with the authoritarian members of the electorate by appealing to the predispositions that support this social psychological orientation. Namely, he advocated for conformity to traditional social norms, the use of force in the form of tougher measures by which to punish criminals, and greater intolerance of nontraditional social groups. Bolsonaro did not have to convince authoritarian voters of his political positions. Rather, his message was aligned with what such voters wanted to hear regarding societal worldviews and moral issues.

There is a long history of research on authoritarianism investigating the role of different threats in activating authoritarian dispositions (Lavine, Lodge, and Freitas Reference Lavine, Lodge and Freitas2005; Hetherington and Suhay Reference Hetherington and Suhay2011; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005; Federico and Malka Reference Federico and Malka2018). Authoritarianism is not politically relevant in a vacuum but influences political contestation when events and elites activate it (Johnston, Lavine, and Federico Reference Johnston, Lavine and Federico2017). Thus authoritarian behavior is activated in reaction to specific threats. Experimental evidence has shown that a perceived threat alters the cognitive strategies employed by authoritarians to extract novel political information from the environment (Lavine et al. Reference Lavine, Lodge, Polichak and Taber2002; Lavine, Lodge, and Freitas Reference Lavine, Lodge and Freitas2005). Others suggest, based on social identity, that in-group norms and out-group leaders during campaigns may play a role in preferences over preferences for personal freedom and individual autonomy (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Moseley, Layton and Cohen2021). Feldman and Stenner (Reference Feldman and Stenner1997), however, found no relationship between economic threats and authoritarianism (e.g., unemployment, economic distress) but did find a relationship between authoritarianism and perceived societal threats.

Political outsiders (e.g., “populists” or “anti-party” candidates) can build an electoral base by reaching out to different voters or emphasizing different policies (Carreras Reference Carreras2012). Such dynamics encourage candidates to seek personal bonds with the electorate and voice their positions to activate dormant and new cleavages. Jair Bolsonaro’s attacks on politically progressive movements and tapping into voters’ fears of crime and public safety, as well as his strong discourse on the demise of traditional moral and cultural values, signals to an authoritarian voter that societal or political order is threatened. It is plausible that Bolsonaro’s election is somehow related to the manifestation of voters’ authoritarian inclinations, as the “authoritarian dynamic” theory posits (see Stenner Reference Stenner2005, 14). However, because of the type of data and the empirical strategy employed here, my result does not speak to whether Bolsonaro is the cause or the result of the Brazilian electorate’s authoritarian orientations observed.

Whether or not authoritarianism remains a salient cleavage of vote choice largely depends on the rhetoric of political elites, especially that of Jair Bolsonaro himself. The results indicate that in 2018 Bolsonaro benefited from the authoritarian electoral cleavage almost as much as from partisanship. The centrality of the presidential election in Brazil implies that subnational candidates tend to organize their campaign strategies around the presidential contest (Samuels Reference Samuels2002). Thus future studies are needed to examine Brazilian elections below the presidential level. If the authoritarian cleavage is deep enough, the effects are likely to be apparent in these lower-level elections as well.

Overall, the authoritarian divide in political attitudes in the Brazilian society is likely to persist through the years. In conditions of social stability, the divide between authoritarians and nonauthoritarians is not particularly large or salient (Stenner Reference Stenner2005). Evidence indicates that the clash between authoritarian and nonauthoritarian worldviews on social, political, and moral issues will endure as Brazil becomes increasingly inclusive and tolerant of diversity, fueling the ire of authoritarians who are largely against such social change. Moreover, authoritarianism is a psychological orientation that exists in various forms among different populations and whose specific determinants vary across time and space in mass political behavior (Feldman Reference Feldman2003).

Clearly, many people remain dissatisfied with the way democracy works even where support for this form of government remains strong. In light of this, an important question for democratic theory to answer is whether Western liberal democracies are able to contain mass public authoritarian impulses (Feldman Reference Feldman, Eugene Borgida and Miller2020). If authoritarians are elected purely because they represent an option within the political arena, then the risks to democracy might not be serious. It is up to democratic institutions and political elites to work as a protective barrier against the rise of autocrats under democratic regimes.

If a candidate enjoys support precisely because he represents a rejection of democratic values, then the election of an authoritarian politician in conjunction with a public that is not committed to democracy is likely to result in democratic decline (Seligson and Tucker Reference Seligson and Tucker2005; Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009). The notion that the overwhelming majority of citizens need to support democracy for democracies to endure is still necessary today (Claassen Reference Claassen2020). If democratic support weakens even in long-established democracies and citizens’ choices reveal a willingness to act against democratic ideals (Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020), then the ability of any democracy to retain the support of a majority of its citizens in the future is uncertain.

Finally, this study is not without limitations. One weakness is the use of a three-item scale. The three child-rearing items have shown acceptable but less than ideal internal reliability. The scale was based on the best available data in the AmericasBarometer, but it nonetheless weakens the construct validity of the measurement. Engelhardt, Feldman, and Hetherington (Reference Engelhardt, Feldman and Hetherington2021) show that adding new items to the existing child-rearing set improves our ability to measure authoritarianism and its predictive effects. That said, the results might be even stronger with longer scales (Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and James2008). Furthermore, in an ideal world, the survey data would have been collected immediately after the election. In the present case, survey interviews were conducted approximately one month after Bolsonaro took office.

Despite these limitations, my analysis reveals that authoritarianism is central to understanding the emergence of leaders with autocratic inclinations within democratic regimes. This study also illustrates the utility of the child-rearing scale for studying political conflict in contemporary Latin America. As an initial investigation into this topic, this work provides a foundation for future research to build on to study both the causes and consequences of authoritarian orientations among the public opinion and political thinking in Latin America. Most important, this study further advances the field’s understanding of the role authoritarianism plays in structuring voting preferences and electoral cleavages in Latin America.

The Brazilian case outlined here builds on previous empirical studies that demonstrate how differences in authoritarian orientations intuitively prepare an individual to be more attracted to some political identities and preferences than others (Feldman Reference Feldman, Eugene Borgida and Miller2020; Federico Reference Federico and van Prooijen2021). The average citizen possesses a range of beliefs, values, and worldview orientations that motivate their interactions with the political world (Federico Reference Federico and Adam2015). How individuals across the authoritarianism spectrum respond to current social and cultural controversies has an impact on their support for policies that limit the rights of certain social groups and on their vote for authoritarian leaders.

Supplementary material

To view the appendix for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lar.2022.32