No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

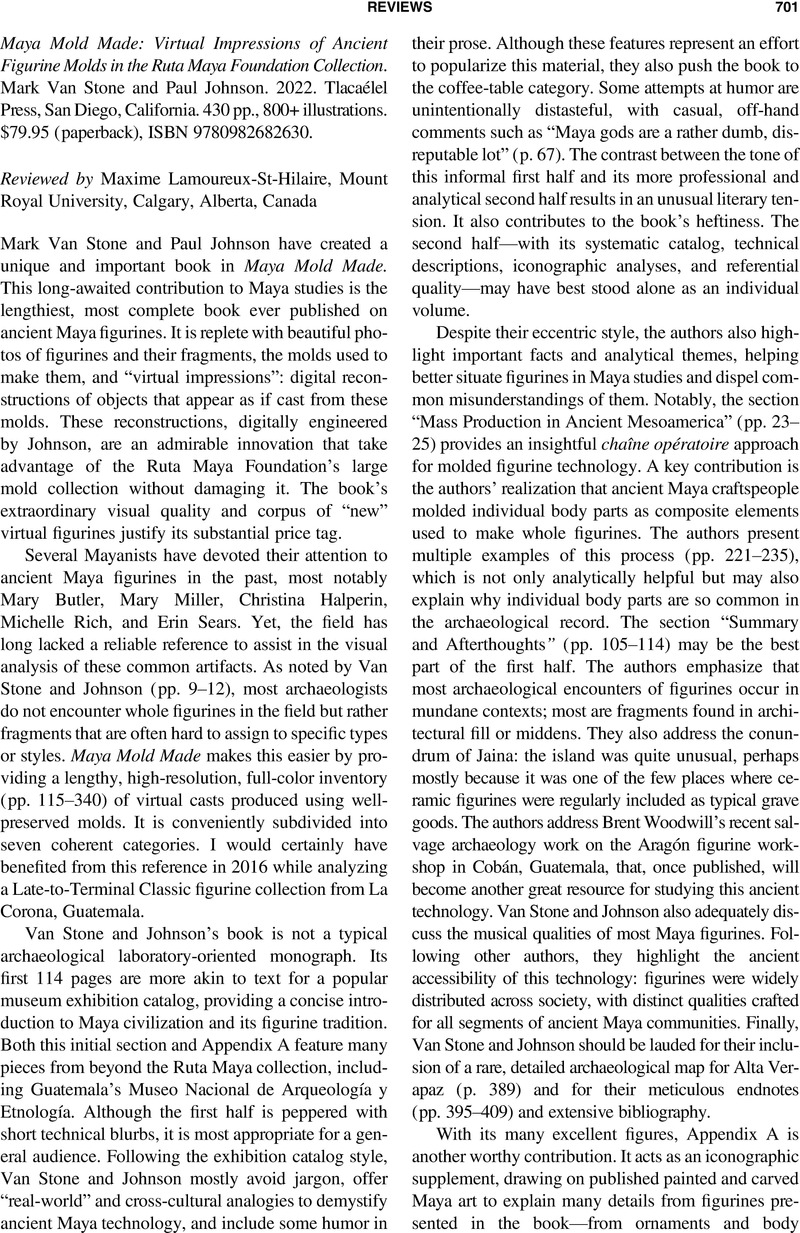

Maya Mold Made: Virtual Impressions of Ancient Figurine Molds in the Ruta Maya Foundation Collection. Mark Van Stone and Paul Johnson. 2022. Tlacaélel Press, San Diego, California. 430 pp., 800+ illustrations. $79.95 (paperback), ISBN 9780982682630.

Review products

Maya Mold Made: Virtual Impressions of Ancient Figurine Molds in the Ruta Maya Foundation Collection. Mark Van Stone and Paul Johnson. 2022. Tlacaélel Press, San Diego, California. 430 pp., 800+ illustrations. $79.95 (paperback), ISBN 9780982682630.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 October 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Review

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for American Archaeology