Introduction

In a contemporary world riddled with crises like global pandemics, climate change, and the loss of linguistic diversity, ‘hope’ seems to be an especially critical attribute. But what is hope and how might sociolinguists and linguistic anthropologists take on the challenge of studying the linguistics and pragmatics of culturally diverse expressions of hope? Miyazaki (Reference Miyazaki2004:14) has described the power of hope as ‘the anticipation of what has not-yet become’ and characterized it as a method of knowledge production. His research on ‘hope’ among the Suvavou people of Fiji is ethnographically based and encourages the goal of grounding the more universalizing interest in hope by philosophers (e.g. Bloch Reference Bloch1986). My goal here is to further explore hope as a specific cultural formation with special attention to the role of linguistic resources and discursive strategies—the ethnopragmatics of Tewa hope in the second decade of the twenty-first century. I offer this study of Tewa hope and the kinds of cultural resources and strategies its members deploy as they confront a growing awareness of the diminishing role of their heritage language and other crises that undermine their continuity as a distinct ethnic group living within the Hopi Nation in NE Arizona of the US.

Like their Hopi neighbors and kinsfolk, the Tewa are not strangers in the strange land of apocalyptic thinking. They know that their history includes their emergence from the wreckage of multiple prior worlds when—to steal an image from W. B. Yeats—the center would not hold, and things fell apart. So, at a time when there are multiple threats to the language, culture, and the very existence of the Village of Tewa (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity1993), its members are deploying cultural and linguistic resources to engage in their own cultural form of hope ‘as a moral call’ (Mattingly Reference Mattingly2010). Mattingly's concept, derived from her research in medical clinics in Los Angeles, demonstrates a cultural association of hope—even when a positive outcome is not tangible or unlikely—with living a good life and being a good person (Mattingly Reference Mattingly2010). Though I highlight other divergences between the dominant society and the Tewa community, the linkage between hope, as a cross-cultural category, and the morally good is a shared cultural practice.

The Village of Tewa consists of about 700 people who are heritage speakers of a Kiowa-Tanoan language their ancestors brought to Hopi lands 320 years ago from their former Rio Grande pueblos in the wake of the Second Pueblo Revolt of 1696. Their distinctive language, now spoken fluently only among its older members, has become emblematic of their persistence as a people. But now that enduring emblem is threatened by an ever-increasing use of English in most domains of social life especially by middle-age and youthful members. In those generations there are comparatively few fluent speakers, though even those who do not speak have some receptive understanding of Tewa. As in many global Indigenous communities, members of the Village of Tewa express a need for heritage language revitalization as they simultaneously confront other threats to their existence as a distinct group.

These include threats from climate change that challenge their ability to grow food in a high desert environment in which subsistence agriculture has always been precarious. It includes the threat of a lack of water sufficient to sustain the people, their animals, and their plants. And more recently it included threats of sickness and death from the Covid-19 virus and the global pandemic which had taken an enormous toll on the community in terms of cases and resulting deaths and reminded its members that they are connected to a larger world exposing them to non-local sources of contagion. In this article, I want to look at these sources of crisis for an Indigenous community that must confront these challenges to survive. In the sections that follow, (i) I better introduce the Village of Tewa and the relevant cultural and linguistic resources of its members, (ii) position myself as an external advocate and this research as a product of collaboration, (iii) describe the multitude of crises that loom over the community and its cultural construal of them, (iv) explore the local form of hope that emerges from Tewa cultural and linguistic resources, and (v) briefly draw conclusions about cultural forms of hope and their study with special emphasis on language revitalization projects more generally.

The Village of Tewa

Located on First Mesa of the Hopi Reservation in NE Arizona, the Village of Tewa (Óóka'a Owinge)Footnote 1 have known several centuries of peaceful stability in their post-diaspora location. Vacating their eastern Pueblo homeland in the Galisteo Basin along the Rio Grande River (see Figure 1), in what is today Northern New Mexico, in the wake of the Second Pueblo Revolt of 1696 (Dozier Reference Dozier1966; Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity1993), the erstwhile Southern Tewa (Thanuge'in T'owa) followed invitations by the Hopi to move to their lands and pacify the region. Though they spoke Tewa, a Kiowa-Tanoan language, and the Hopis spoke a Uto-Aztecan language, their cultural adaptations were otherwise quite similar. Like the Hopi, the Tewa were agriculturalists though they would need to learn ‘dry-farming’ technology from these new neighbors since their new home would not contain any permanently flowing rivers that could be used for irrigation as in their former homeland (Schachner, Nicholas, Sinensky, & Bocinsky Reference Schachner, Nichols, Sinensky, Kyle Bocinsky, Bernardini, Koyiyumptiwa, Schachner and Kuwawiswma2021). Like the Hopi, the Tewa had a stratified society in which those highest in the ceremonial orders also possessed considerable political power in their communities. Though their Southern Tewa social organization featured a moiety system common to Eastern Pueblo communities, they would quickly adopt a clan organization based on the model of their Hopi neighbors. Though considerable accommodation to the Hopi and their environment was inevitable, the Tewa—unlike almost all of the many dozens of Pueblo Revolt diasporic groups—would never lose their language and would continue to use it as an important language in their linguistic repertoire. Though they would learn Hopi, and later English, the Tewa language often masked new cultural features and erased other evidence of apparent change. The word for ‘clan’—a prominent feature of Hopi society, but not originally Tewa—was a semantic extension of the Tewa word for ‘people’ t'owa. Many clans were named similarly to Hopi totemic names—Bear, Sun, Corn, and so on—but encoded in familiar Tewa vocabulary rather than Hopi. Though the Tewa encountered some difficulties in their adjustment to their Hopi neighbors that resulted in the ‘linguistic curse’ Tewa put on the Hopi, the groups eventually managed to live together and cooperate successfully. This, now more than three-centuries-old, ‘curse’ was a form of Tewa cultural revenge on the Hopi for failure to show appropriate gratitude for Tewa military service against Hopi enemies. In the wake of the Second Pueblo Revolt against the Spanish in 1696, Hopi First Mesa clans had invited their ancestors to move three hundred miles west to Hopi territory. According to the agreement, the Tewa would come and defeat Hopi enemies and be rewarded with land and other resources. But when the Tewa decisively defeated Ute marauders, Hopis failed to honor the agreement. The Tewa responded by placing a curse on the Hopi. This episode is recounted in narratives in which the speech of Tewa leaders to their Hopi counterparts is dramatically reconstructed as in the following translation (Dozier Reference Dozier1954:292).

Because you have behaved in a manner unbecoming to human beings, we have sealed knowledge of our language and our way of life from you. You and your descendants will never learn our language and our ceremonies, but we will learn yours. We will ridicule you in both your language and our own.

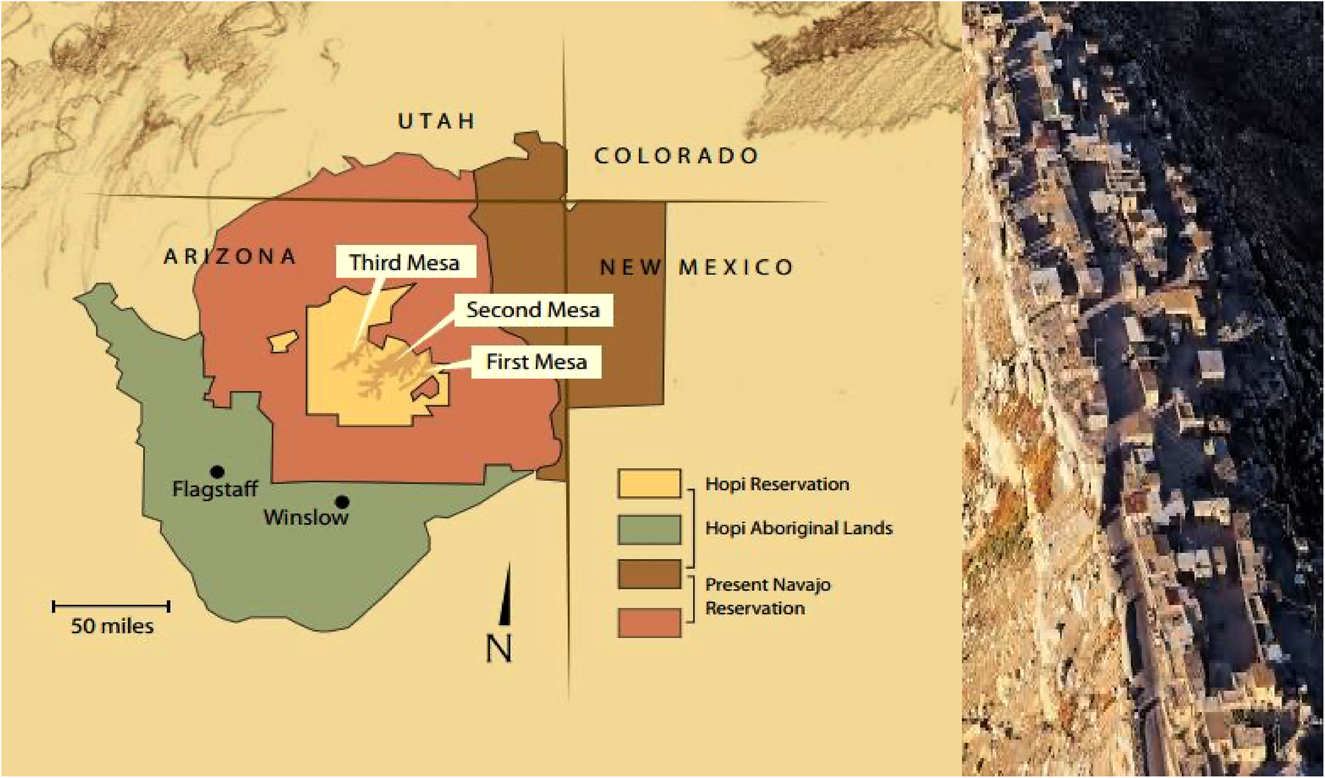

Figure 1. Map of Hopi Reservation in US Southwest and aerial view of First Mesa (The Village of Tewa is centered around the open plaza at the lower right).

As a metalinguistic statement about language and identity, the curse is multiply meaningful. It is remarkable in the powerful way it emblematizes the Tewa language to group identity, but it is also especially noteworthy as a valorization of Tewa asymmetrical bilingualism. Rather than view their need to learn Hopi as a consequence of their status as a displaced minority, the Tewa account views their asymmetrical bilingualism as a willful cultural achievement and as persisting evidence of Tewa moral superiority. The ‘curse’ narrative is a critical part of Tewa initiation ceremonies, and it is materialized in a petrified wood marker, serving as a monument of sorts, between the Village of Tewa and the adjacent Hopi Village of Sichomovi, where the historical curse occurred.

Though this narrative reflects tensions between the groups during the period immediately after the arrival of the Tewa around 1700, relations between Hopi and Tewa communities improved markedly since then. Many marriages in the First Mesa area—where the Village of Tewa resides—are intermarriages with Hopi spouses. These are still regulated in accordance with the matrilineal system of the Hopi where men will move to their wife's village. In addition to intermarriage, the Tewa now also developed a ceremonial cycle in which each clan ‘owns’ a particular ceremony and supplies the leadership for that event. As with the Hopi, Tewa individuals work to support the ceremonial performances of other clans and expect members of those other clans to do the same when it is time for their own clan's ceremony.

Tewa indigenous language ideologies emerge from the cultural focus on ceremonial practice and the enregisterment (Agha Reference Agha2003; Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003) of a culturally prominent form of speech known as kiva speech (te'e hiili) as the cultural exemplar of proper language use. This model includes such attributes as indigenous linguistic purism, strict linguistic compartmentalization, regulation by convention, and linguistic indexing of identity (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity, Schieffelin, Woolard and Kroskrity1998). Historical linguistic studies indicated that the linguistic purism that scholars such as Dozier (Reference Dozier1956) observed, was not created in the crucible of Spanish colonization, but rather preexisted it, not just for Tewa but for many, if not all, Pueblo groups (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity1993, Reference Kroskrity, Schieffelin, Woolard and Kroskrity1998). Loanwords from other indigenous languages, spoken by neighboring groups for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, were exceedingly rare. This long-standing and consistent cultural preference for ‘indigenous purism’ manifested as a dispreference for loanwords from all other languages and a strong preference for extending native vocabulary to fill lexical gaps. For the Village of Tewa, there is extremely minimal borrowing from Spanish (seventeen words) and Hopi (two words), despite long periods of past or current multilingualism (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity1993). But this practice of indigenous purism, for the Tewa, coexists with multilingualism to encourage a multilingual adaptation with little or no code-switching. This ideal is naturalized by some as a linguistic version of a strategy that combines the ideologies of purism and compartmentalization —such as the growing of six distinct colors of corn by growing them in separate fields. Archeologists like Ford (Reference Ford1980) attributed this practice to a strategy, encouraged by the ceremonial system of a people living in a harsh environment, that eschews the maximization of a single field in favor of the security of planting many distributed fields in an area characterized by great micro-climatic variation such that flash floods, sandstorms, drought, and other disasters would not completely destroy a family's ability to grow food. The naturalizing of linguistic compartmentalization by explicitly connecting it to a ceremonially prescribed agricultural practice promotes a sense of convergence between traditional practices and a natural order and conveys the partnership of the natural and social worlds.

‘Regulation by convention’ and linguistic indexing of identity are other pervasive attributes of Tewa discourse that are traceable to the power and influence of kiva speech—the ceremonial register associated with a theocratic elite who held both religious authority and political power. What Newman (Reference Newman1955) first called regulation by convention could perhaps be better understood as a value on what Bauman (Reference Bauman, Duranti and Goodwin1992) termed traditionalization—linguistic and discursive strategies designed to tether a text or a performance to a traditional model. Elsewhere I have illustrated how the ‘sacred chants’ announcing ceremonies of chanter-chiefs have provided a model for mundane work-party, grievance, or birth announcements (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity1992). But the most powerful, as well as succinct, example occurs in Tewa storytelling as in (1) below—a representative opening sentence in a traditional Tewa narrative.

(1) Owae;heyam-ba Bayaena-senó ba na-thaa;.

long ago-ba Coyote-elder-ba 3:sg-live

‘Long ago, so they say Old Man Coyote so he was living.’

In this sentence, traditionalization is achieved by a generically prescribed over-use of the evidential particle ba ‘so they say’. While only one of these is grammatically necessary to convey evidential meaning, narrators typically use two or more per clause to perform the voice of the storyteller and establish the chain of authentication to ancestral sources (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity2009). Though I have only offered two examples, many others could be provided to show the strong preference for using traditional models.

Much as a practitioner's ceremonial identities and the special names for these identities emerge in ceremonies, so other linguistic forms are associated with other indexed identities. Both a ceremonial emphasis on linguistically constructed identities and a folk history that clearly connects Tewa identity to the Tewa language combine to make the heritage language an emblem of identity and an explicit topic of indigenous discourses of language and identity. In Tewa, a metadiscourse involving language and identity is especially well-developed. Older Tewa have a saying, Naavi hiili naabi woowatsi na-mu ‘My language is my life’, which is widely used with either a singular or non-singular first-person pronoun. In its singular form, the saying usually conveys a recognition that one's biographical choices have a linguistic residue. The non-singular version is most often used to express pride in the purity of the local Tewa language by contrasting it with Rio Grande Tewa in New Mexico which, from the Arizona Tewa perspective, is characterized as riddled with Spanish influence. But in addition to relating a particular language to identity, the Tewa also use ‘the linguistic curse’ as a celebration of their asymmetrical bilingualism with Hopis who are said not to be able to learn Tewa because of the efficacy of the curse.

This brief sketch of the Village of Tewa can be further winnowed into three cultural features that are both resources and vulnerabilities for them.

(i) Like those of other indigenous people, many of their distinctive language ideologies emerge from their means of production and the cultural worldview in which it is practiced. In such a view, humans are a vital part of the natural order and successfully grow food not just through the hard work and botanical knowledge associated with farming but also through prayer and maintaining proper relations with katsina spirits who enable seeds to sprout, plants to grow, and precipitation to fall.

(ii) Tewa language ideologies promote a cultural attention to an authoritative practice of ‘speaking the past’—relying on replicable ceremonial practices, ancestral authority, indigenous purism, and the project of maintaining their languages as maximally distinctive, and a conviction that relevant identities are embodied in specific languages.

(iii) The history of the Village of Tewa and its citizens is one that emblematizes their language, rhematizing it as a sign of their distinctive identity (Gal & Irvine Reference Gal and Irvine2019). Given the centuries of culture contact and intermarriage with the Hopi, their language and their unique history persist as really the only distinctive attributes of its community members. As mentioned above, the language ideology that views language and history as consubstantial, makes the Tewa language the ultimate emblem of Tewa identity.

Positioning the researcher and the research

Any attempt to talk of humans and hope is necessarily interpretive. Such accounts of the pragmatics of hope not only examine material evidence and observable actions, they also impute intellectual understandings and affective appreciations. I attempt to understand Tewa hope, not as a member of that community but as a researcher who has conducted long-term research in the Village of Tewa. In my five decades of research involvement with the community, I have resisted what Czaykowska-Higgins (Reference Czaykowska-Higgins2009:20) has called ‘the linguist-focused model of research’ and attempted to take decolonizing approaches, which emphasized the importance of research-partnerships, greater collaboration, and community-based research (Shulist Reference Shulist2013). As a linguistic anthropologist interested in language ideologies, I was prepared to use ethnography as a way to better understand Indigenous linguistic practices as well as Indigenous understandings of their heritage language and other languages in their linguistic repertoire (Shulist & Rice Reference Shulist and Rice2019).

Though my research relationship with the Village of Tewa began back in 1973, well before the publication of such important works on Indigenous methodologies as Smith's (Reference Smith1999) Decolonizing methodologies, and more recent contributions by Wilson (Reference Wilson2008), Kovach (Reference Kovach2009), Lambert (Reference Lambert2014), and Leonard (Reference Leonard2017), I was influenced by both a political climate of activism and scholarship that emphasized the need for community-based research. Vine Deloria, Jr. had just published Custer died for your sins: An Indian manifesto in Reference Deloria1969 and its mocking of anthropological research for its penchant for following academic research agendas completely divorced from the needs and relevancies of Native American communities signaled the need for research reform. Hale (Reference Hale and Hymes1972), in an important article published in Hymes's (Reference Hymes1972) Reinventing anthropology, emphasized the importance of Native knowledge and the critical need for decolonizing linguistic practice and bridging the divide between academic and Indigenous communities. This research anticipated later publications on language endangerment (Hale, Craig, England, Jeanne, Krauss, Watahomigie, &Yamamoto Reference Hale, Craig, England, Jeanne, Krauss, Watahomigie and Yamamoto1992) and language revitalization (Hinton & Hale Reference Hinton and Hale2001) that would require a rethinking of academic research in Indigenous language communities and more of a re-orientation to community-based research. It also provided a transition to research that was more fully collaborative (Shulist Reference Shulist2013), involved greater participation by the language community (Czaykowska-Higgins Reference Czaykowska-Higgins2009:19), and was guided by Indigenous theories (Leonard Reference Leonard2017).

Working in the Village of Tewa as part of this research paradigm shift, I was also anticipating current emphases in Indigenous methodologies since my early research included Indigenous storytelling traditions (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity1993, Reference Kroskrity and Kroskrity2012). By attempting to learn the aesthetics and morality of Tewa storytelling, I was introduced to a key speech event for intergenerational cultural transmission. I learned to regard Indigenous storytelling practices as the wellspring of Indigenous perspectives on language, culture, and the vital transmission of these knowledges within communities. I learned to value what Stó:lō scholar Jo-ann Archibald (Reference Archibald2008) would later theorize as storywork: experiential narratives that constitute epistemic, theoretical, pedagogical, and methodological lenses through which language reclamation can be practiced and studied. As method, storywork provides data in the form of firsthand accounts and Indigenous values in cultural transmission as a means through which to gain insight into the significance of language reclamation in diverse communities (Archibald Reference Archibald2008:132–40). Brayboy (Reference Brayboy2005:427) asserts the critical importance of storytelling, ‘Stories serve as the basis for how our communities work.’ I have (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity and Kroskrity2012:4) also observed how Indigenous storytelling provides ‘narratives for moral instruction, healing, and developing culturally relevant tribal and social identities.’ Archibald, Lee-Morgan, & De Santolo (Reference Archibald, Lee-Morgan, De Santolo, Archibald, Lee-Morgan and Santolo2019:7) assert: ‘As a methodology, Indigenous storywork equips our communities not only to voice, listen to, and understand our stories with “respect, reverence, reciprocity, and responsibility” (Archibald Reference Archibald2008:140) but collectively to become an Indigenous research community’. This Indigenous perspective encourages us to explore the ways in which language reclamation relates to the more encompassing Indigenous projects of resilience, cultural sovereignty, linguistic self-determination, and social justice. And toward these ends, I agree with McCarty, Nicholas, Chew, Diaz, Leonard, & White (Reference McCarty, Nicholas, Chew, Diaz, Leonard; and White2018) that while storywork theories and methods do emphasize the more universally available source of Indigenous knowledge represented in storytelling, they also recognize the diversity of these traditions (Archibald Reference Archibald2008:140). Some of this diversity, of course, is represented in the form of protocols not only about displaying appropriate listening behavior (e.g. Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity and Kroskrity2012; Nevins & Nevins Reference Nevins, Nevins and Kroskrity2012) but also extending to concerns about who can tell and hear stories (e.g., Debenport Reference Debenport2010b). These included forms of concealment not only directed at outsiders but also insiders according to clan membership or gender identity.

Working with Indigenous storytellers in the Village of Tewa provided a key means for me to approximate Indigenous methodologies even in the role of an external advocate. In the earliest period of my research, I worked with relatively few people in part because documentation was a controversial activity in the 1970s. I have previously reviewed the early history of my collaboration with Village of Tewa elder Dewey Healing (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity2021), who modified a cultural stance of non-collaboration with outsider linguists into conditional cooperation when he realized that linguistic research could be practiced not as academic extraction but as a means of resource creation for a Tewa language community that was experiencing Tewa language loss. Though I had been introduced to a linguist-focused (Czaykowska Higgins Reference Czaykowska-Higgins2009:20) model of research in graduate school, my more ethnographically based engagement with the Tewa language community introduced me to local practices and encouraged an ethical transformation in my research which became increasingly more community focused (Debenport Reference Debenport2010a). Around 2002, the Village of Tewa began to develop its own protocols for researchers. I was asked to make several presentations about what a language documentation project would look like and how it would fit with the community's own interests in creating resources for language classes that were being planned at that time. After a series of community meetings between 2007 and 2012 in which about eighty people (in a community of 700) voiced their opinions—mostly expressing enthusiastic support, the Village Board approved a Tewa Practical Dictionary project and provided meeting space and other support. Since that approval in 2012, I have worked every year with members of a Dictionary team. These were in-person meetings from 2012–2019 and since the pandemic in 2020 these have been weekly meetings on zoom. In early 2022, the Project produced a fifth edition of the limited circulation dictionary which is used primarily as a resource for teachers and students. The project is still continuing as of the writing of this article.

In sum, my positionality is that of a linguistic anthropologist who is not a member of the community but who has conducted long-term, community-based research over five decades and who has been privileged to be allowed to learn an Indigenous language that is typically concealed from non-Tewas. My research is highly collaborative, and I am permitted to talk about it as well as the language practices of the community as long as I do not circulate reference or pedagogical materials or treat in detail ceremonial activities and associated forms of speaking. As a linguistic anthropologist and long-time friend of many members, I have written this article as an expression of my admiration of their agency and persistence—their survivance (Vizenor Reference Vizenor2008; Wyman Reference Wyman2012; Davis Reference Davis2017).

Crises

Crisis, as a useful analytical category, ‘refers to structural processes generally understood to be beyond the control of people but simultaneously expressing people's breach of confidence in the elements that provided relative systemic stability and reasonable expectations for the future’ (Narotzky & Besnier Reference Narotzky and Besnier2014:54). While this concept of crisis suggests an objectivist concern with ‘real’ and quantifiable threats, it also allows us to understand such threats through the lens of cultural worldviews that magnify, minimize, or endow significance to destabilizing outcomes. Each of the crises confronted by the Tewa in the first two decades of the twenty-first century had some destabilizing effect but collectively their impact was especially powerful. Confronting these challenges, most people attempt to retain a measure of control over the activities and matters they can control. Since crises are culturally construed, those experiences provide a necessary context for understanding the cultural production of hope.

Climate change

There is no debate about the existence of climate change in this high desert community. It is all too real. In a land with no rivers or lakes, the Tewa—like their Hopi neighbors—have traditionally relied on ‘dry farming’—a technique of planting in winter run-off areas and relying on a sandy soil to insulate sub-surface moisture that would nurture Indigenous varieties of maize capable of sending their roots deep (Schachner et al. Reference Schachner, Nichols, Sinensky, Kyle Bocinsky, Bernardini, Koyiyumptiwa, Schachner and Kuwawiswma2021). This technique, which has served Indigenous people well on the Hopi Mesas for more than a thousand years and enabled them to sustainably farm in an arid environment, presupposes a significant winter snowfall. But most winters in the past five to ten years seemed to produce comparatively little snow. Even though in the winter of 2018, when snow finally fell in abundance, it did not seem to make a lasting difference. More water drained into the fields but the hot winds that followed brought a penetrating heat and dryness that, according to many Tewa farmers, wicked needed moisture away, leaving fields inadequately watered, leaving corn plants stunted, and leaving people—particularly those who were tending and relying on the fields—more convinced than ever that something was very wrong. If a winter that provided so much snow that people had trouble opening their doors against waist deep drifts, or finding roads that were passable did not do the trick, what could? From one of the driest years to one the wettest, the hallmark of climate change and its fickle and erratic effects was now a conspicuous feature of life on the mesas. The pattern, or lack of pattern, continues into summer 2021 as people complain of wind, smoke from fires in nearby Flagstaff, and the 2022 summer monsoon flooding of Polacca Wash, that covered the main highway on the Hopi Reservation in mud and flood debris, and destroyed many Tewa homes (Hopi Tutuveni 2022). The rapid juxtaposition of drought and uncontrollable flooding is especially disturbing to the Tewa.

Environmental degradation/lack of water

Other changes also amplify the perception that the hard life on Hopi lands is getting harder. The springs on which Hopis rely for drinking water are not recharging—some are at record low points and do not provide adequate water for people, animals, or plants. Some of the springs, like much of the well-water available to Hopis, contain high levels of naturally occurring arsenic that make it unfit for human consumption. The Hopi Reservation water crisis is quite real and as a people with no surface water continually running across its lands, the Tewa there—like the Hopi—must rely on cooperative arrangements that they might strike with the Federal government, the Navajo Nation, the City of Flagstaff, and other competitors for claims to water rights. Resources that once could be counted on—in local theory also called ceremony—as a form of reciprocity and collaboration with the natural world iconized by the Water Serpent Avaayun— through proper prayer and ritual—are now the objectives of designated Hopi Tribal negotiators and their attorneys who must argue and compete with neighboring Navajos or the City of Flagstaff for water rights to ensure a source of clean drinking water. Disaster has been averted in 2022 as a cooperative arrangement has been worked out with the Navajo Nation which will run an underground water line to the First Mesa area while it provides similar infrastructural support to Navajos in Jeddito. This solves an immediate problem, but it does not erase some lingering concerns.

Some Tewa feel that the failing natural springs are due to corresponding failures by Hopis and Tewas who forfeited their role as guardians of the natural world when they, along with the Navajo, signed deals with Peabody Coal that gave Big Energy the right to mine coal and use precious subsurface water as an underground slurry to move coal particles (Whiteley Reference Whiteley1998). Tewa, like the Hopi majority, generally take this role as environmental guardians very seriously and, insofar as land is concerned, identify as Hopis who ‘as part of their covenant with Maasaw … were allowed to cultivate the land if they agreed to be stewards of the earth’ (Kuwaniwisiwma Reference Kuwanwisiwma, Powell and Smiley2002). Though the Hopi Tribe (which includes the Village of Tewa) refused to renew its contract in 2019, this refusal comes with a massive loss of revenue and a lingering sense of colonial violation in a domain in which Indigenous people had compromised their values. From the objectivist perspective of the natural sciences, this has little to do with climate change, but it is connected in many Tewa minds and hearts as part of a single phenomenon involving an Indigenous people and their very moral relationship to their lands.

Diminishing use of Tewa

Outside experts will think that there is no significant connection between climate change, environmental degradation, and the Tewa and their language. But many Tewa will say that this is not the case. Some are concerned that the ceremonies overseen by certain clan leaders may not be conducted properly and this lack of ritual rigor and ceremonial protocol may be a factor in the current climate imbalance. A feeling of uneasiness abounds in one of the two kiva groups that leaders of the other lack sufficient heritage language competence to properly conduct their ceremonies on behalf of the Village. Carbon emissions certainly have something to do with the climate crisis, but as some of my Tewa co-workers confide ‘the ceremonies connect us in the right way to this world, they keep things together, and we can't do the ceremonies right without the knowledge of our language’. This dynamic relation between cultural actors and the natural world is a naturalization of a reciprocal relation—providing human stewardship, proper prayerful thoughts, and ceremonies, on one side, and ongoing natural resources and the blessings of nature on the other. The most important product of Tewa culture—corn in its six colors—provides food to eat and differentiated colors that are essential to ceremonial life. But this is the result of Tewa practices of planting only one color per field and planting many fields far from one another (Ford Reference Ford1980)—a survival strategy that fits the microclimatic variation of the Hopi mesas. This fundamental act and its naturalization are the rationalization for Tewa language ideologies of linguistic purism and strict compartmentalization and for an unusual species of multilingualism without loanwords. But for some Tewa the moral order, usually ascribed to the nature of things, is damaged—if not broken—and many Tewa see themselves as having some responsibility to repair the situation.

The emblematic Tewa language, while still widely spoken among older adults, is rarely heard among young people. Though the lack of heritage language vitality is less severe than in many Native American communities in the US, thus is certainly partially due to the settler-colonial imposition of boarding schools and the hegemonic influence of English which is critical for economic survival on the Reservation. Schooling occurs in English and virtually all employment on the reservation requires it. Tewa efforts at language instruction are limited to after-school classes that attempt to serve all youth regardless of their highly variable proficiency in Tewa. Many older Tewa are deeply concerned about the continued existence of a heritage language that is so much a part of their identity as a people. Yet there is no unifying plan. Members of one kiva group strongly support language documentation efforts and the after-school classes. They are part of a majority of Tewa villagers who see language revitalization as important and necessary. But the leaders of the other kiva group are adamantly opposed to either documentation or teaching.

The pandemic

An additional and especially devastating crisis was experienced in the form of the pandemic which hit the Hopi Reservation very hard by mid-2020, producing positive tests in almost a third of residents and many deaths particularly for those with pre-existing conditions.Footnote 2 In various attempts to halt the spread of the virus, the Hopi Tribe closed road access into or out of the Reservation, imposed lockdowns and curfews in all of its villages, and banned—with the cooperation of ceremonial leaders—all overt sacred and social dances, and any group meetings. But while these measures helped to slow the spread of the virus, they could not prevent the pain and suffering of those who were its victims, and many Tewa families still grieve for one or more of their family members who died. Several members of the Tewa Dictionary Team, assembled after the Village Board approved the project in 2012, suffered deaths in their families. The loss of many elders who were considered exemplary speakers of Tewa contributed to the accumulated sense of precarity.

If these collective crises have had a unifying theme perhaps it is as a potentially humiliating lesson in the impossibility of the strictly local. The Covid-19 virus, like climate change, environmental degradation, and encroachment of English, are evidence that the community participates in a variety of systems that oppress it in various ways. That the disruption undermines confidence in existing structures to retain, maintain, or attain an orderly balance is apparent. Ceremonial leaders—at least some—cannot be trusted to perform their ritual obligations properly. Families and homes mostly do not live up to the responsibility of teaching youth their Tewa language. Tribal government does not seem to have an iron-clad plan for solving the water crisis on the Hopi Reservation let alone the larger problem of the woefully underdeveloped Reservation economy now that Big Energy corporations have been sent packing. Climate change threatens to make a precarious ecological environment into an impossible one as less rain and snow fall, the arid winds become more frequent, and the temperatures move to abnormal extremes. This is not the devastation, represented by Lear (Reference Lear2006), that Plenty Coups and the Crow confronted after the loss of both buffalo and horses threatened to utterly transform their Indigenous world and require a ‘radical hope’. Lear (Reference Lear2006:103) defines this form of hope in the following manner:

What makes this hope radical is that it is directed toward a future goodness that transcends the current ability to understand what it is. Radical hope anticipates a good for which those who have the hope as yet lack the appropriate concepts with which to understand it.

But rather than the more devastating cultural collapse experienced by the Crow, the Tewa crises are more like destabilizing challenges to their sense of continuity as a people. They have not been forced from the Hopi lands they have occupied for more than several hundred years but their confidence in farming them as a distinct people has been undermined.

Hope in Tewa cultural practice

A conspicuous feature of a Tewa cultural response is the elevation of moral value over economic value as one might expect in a society socioeconomically predicated on the survival of the many rather than the thriving of the few. Something like a ‘moral call for hopeful action’ is projected in the words and actions of many Tewa and it most definitely motivates people in the present to work toward a better future (Antelius Reference Antelius2007; Mattingly Reference Mattingly2010). Since the crises pose threats to the very existence of the Tewa as a distinct people, they require a response to these threats, some of which, like climate change, appear permanent and others, like the pandemic, perhaps temporary. For them, this required reorientation to an unknown future is ‘centered around social reproduction, that is, the objective and subjective possibilities to project life into the future (“hope”)’ (Narotzky & Besnier Reference Narotzky and Besnier2014:55). It is about maintaining and adapting a form of life to the ‘not yet’ of an uncertain future (Bloch Reference Bloch1986). But what Miyazaki (Reference Miyazaki2004:5) calls ‘the radical orientation of knowledge’—appropriately amended to also include ‘action’ by Borba (Reference Borba, Peck, Stroud and Williams2019:167)—cannot be properly understood for the Tewa through either universalist philosophical assumptions or a phenomenology that ignores linguistic categories and communicative practices, as Crapanzano has asserted (Reference Crapanzano2003:11). Guided by his suggestion, I want to begin to understand Tewa hopeful knowledge and action by seeing how it is informed by the Tewa language and the ideologies that scaffold its usage.

The grammar of Tewa hope

As a linguistic anthropologist and member of the community's Village of Tewa Dictionary Project, I have had a close-up view of Tewa grammar and use. The Tewa language provides three main ways to express ‘hope’. There is the adverb agáedimo’ ‘hopefully’, which expresses a generalized wishing for or wanting the result of the verb usually realized with ‘obligative’ aspect and best translated as ‘will’ or ‘should’.

(2) Agáedi;mo’ din-hae;lae-pay-mí.

‘Hopefully all (crops) will grow for me!’

The other ways of expressing something like ‘hope’ in Tewa are two verbs. Both of these verbs, -piiva and -yeet'an, have semantic fields that give them alternate or secondary senses that are not shared by English ‘hope’.

(3) O-kwé;-piva.

‘I am hoping for rain.’

(4) Óyyó na-mu-mí-na'a-di deh-yeet'an.

‘I am hoping for something good.’

My translations of (3) and (4) both use English ‘hope’ for the verb but native speakers say that -piva could also be translated as ‘want’ and/or ‘expect’ and that -yeet'an also means ‘aiming at/for’. (It is the same verb that one would use in talking about aiming a rifle or a bow and arrow.) Both words are considerably more agentive than English ‘hope’. It might also be pointed out that performative language ideologies and familiarities with ceremonial practice predispose most Tewa to view thoughtful (silent) prayer as a potentially powerful action or as an embryonic form of action. Tewa linguistic categories begin to suggest a more distinctly cultural form of hope inflected for agency, motivation, and future-orientation. In her philosophical discussion of hope, Waterworth (Reference Waterworth2004:8–10) usefully contrasts expectation and anticipation, viewing the latter as a critical component of hope. The Tewa seem to agree but Tewa hope is still more than mere anticipation. The linguistic categories guide Tewa speakers, as well as those who analyze the language, to a way of seeing hope as linked to incipient action. In keeping with a Whorfian emphasis, not on some misrecognized caricature of linguistic determinism, but rather on what he saw as the dialectic of language structure and cultural uses of language (Whorf Reference Whorf and Carroll1956:156), we can see how the Tewa language has adapted well to the demands of a difficult natural environment that requires continuous attention and appropriate actions to produce a sustainable culture. This is manifested not only in their agentive conception of hope but also in their adaptations to Hopi patterns of land use and dry-farming. These adaptations involved the appropriation of Hopi concepts of social organization, such as land-owning clans, even though such borrowings were hidden through the semantic extension of Tewa words—like t'owa (originally ‘people’ but later ‘clan’). Much like the farmers in this exacting landscape, Tewa speakers are predisposed by their language, and language ideologies, to be ‘always getting ready’ (Schachner et. al. Reference Schachner, Nichols, Sinensky, Kyle Bocinsky, Bernardini, Koyiyumptiwa, Schachner and Kuwawiswma2021:132).

Articulating a useful notion of hope especially appropriate for Indigenous communities, Heller & McElhinney (Reference Heller and McElhinny2017:254–55) provide ‘the strategies undertaken on the terrain of language to repair past harm and, on that basis, to move forward to more equitable and peaceful futures’. Colonized twice in their history—by the Spanish and later by the United States—the Tewa, through language ideologies of Indigenous purism and strict compartmentalization, had potent tools to resist assimilating influences even while enduring colonial subordination. But the power and attraction of hegemonic English in popular, mediatized culture and in the conduct of all US and Hopi institutions now makes it the most formidable language they have encountered. Today, documentation efforts and Tewa language classes provide a new means of resistance even if these activities can at best preserve Tewa as second language for Tewa youth. I discuss this further in the next section.

The moral call for hopeful action is not merely a stance or an attitude, it is embodied in responses to several of the various crises. While climate change is clearly not purely a local issue, the Tewa have adopted new green technologies like solar power to run their community center—the administrative engine of the Village. And, in the hopeful spirit, they have identified with other native groups and in 2017 even sent a delegation to support resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline offered by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe at the border of North and South Dakota. Until recently, this type of intertribal support has been rare. Regarding their own environmental degradation, Tewas and Hopis chose the moral path of their own values over profit from mining leases. Since the water and snow that fall to the ground represent the transubstantiated spirits of their ancestors (Whiteley Reference Whiteley1998), Tewas and Hopis are morally right to refuse further energy leases even if they are punished economically for it. The Hopi Tribe, which includes the Tewa, has repeatedly voted down gaming and, so far, refused to include it in their plans for economic development on the Reservation. ‘That [gaming] would bring many unwanted things,’ I am told by some. Among those things are temptations to youth to move away from their culture in the food they eat, the beverages they drink, the professions they might work in, their place of residence, and further symbolic domination of mainstream popular culture.

The Tewa response to Covid was one of almost complete compliance with lockdown, curfew, and social distancing required by the Tribe to combat infection rates that amounted to almost one-third of the Reservation population. Similarly, vaccination rates are very high as people look to be protected so that they can resume ceremonial activities and social dances, and other public assemblies as quickly as possible.

Hope and Indigenous language revitalization

The language programs represent yet another hopeful response. Both the documentation represented by the Tewa Dictionary Project and the language classes for youth offered in the community center show that there are still efforts being made to maintain the heritage language and to create resources for its transmission across generations and for general circulation in the community. On the positive side, classes are lively and well attended by as many as fifty participants, ranging in age from youth to middle-aged participants. A recurring problem in offering these classes is that they are basically offered in a one-size-fits-all format that is incapable of offering a graded or more individualized experience. But the classes themselves become an activity that is community building and for all of its shortcomings as an under-funded grassroots effort, it is still widely regarded as a success. As Debenport (Reference Debenport2015:112) has cogently observed, Indigenous language revitalization efforts are often viewed as ‘“successful” despite the lack of quantifiable results or the predictions about language “death” made by academics and media figures’. Linguists may want to evaluate success through measures of fluency but many Indigenous language communities, including the Tewa, prefer to appreciate what Perley (Reference Perley2011) has called the ‘emergent vitalities’ of new forms of heritage language use that push back against a more totalizing heritage language loss. Youth who would not otherwise learn Tewa can attend classes and use the language there to develop the confidence to begin speaking with older relatives. Middle-aged speakers can find in the classes a context for further developing their conversational use of the language. Classes may be one-size-fits-all in format, but speakers can integrate their experience into their lives in ways that are individually appropriate. It is a way to go beyond the use of Tewa greetings like Sengidimo’ (lit. ‘with health and strength’) in everyday speech and Facebook entries to develop further conversations.

But while the classes do provide an important but somewhat formal educational resource for intergenerational communication in Tewa, the informal education of a still rich cultural life in the Village of Tewa provides another especially welcome and instructive one. Adding to the rich ceremonial calendar of the Tewa and their Hopi neighbors is a growing interest in sponsoring and performing Tewa social dances of various types. These are especially popular and attract participation and engagement from all age groups. What is especially remarkable is that they require performers to perform and compose both old and new songs. These songs are taught line by line in almost daily practices for weeks leading up to the event. This provides a rare opportunity for explicit linguistic instruction in context and is an excellent opportunity for learners to master a collection of songs and to perform them in public to a supportive audience. One song regularly sung during Yaaniiwe social dances was composed by Dewey Healing almost fifty years ago. I know from our research together that he composed it to express his concern about the maintenance of the Tewa language. He recognized a pattern of diminishing Tewa use long before others in his community and began to take steps toward language documentation (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity2021). A gifted songwriter and singer, he composed ‘Where shells are shaken by the waves’—it was his expression of hope, one that would lead to an innovative collaboration with the author of this article and ultimately to the beginning of the current Village of Tewa Dictionary Project. Though the song was composed long ago it is still regularly sung in these social dances and each time the song is taught word by word and line by line to the rehearsing performers including many young adults.

The content of the song transports us first to the lake from which the Tewa say they emerged into this world—possibly Blue Lake, Colorado. Shells are associated with that place as well as the Tewa name of their Village—Óók'a Owinge (lit. ‘Shell Village’). This primordial time of the ancestors is linked to the present action of the singers who are exhorting the people to follow the ancestral ways that are being and have been provided by the elders. Moving from present, the songwriter looks to the youngest generation and includes them in the lyrical embrace. The final line is future-oriented and conveys, with the rhetorical blending of a toast and a prayer, the hope that the Tewa people will live on!

Here we see the Tewa language song text, and its many contextualized performances, used to create an ancestral language-mediated chronotope (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin, Emerson and Holquist1981). This is nostalgic representation of an idealized past that is materialized in present actions (texts and performances) and inclusively oriented to a future embodied by grandchildren and great-grandchildren. This is the Tewa language community reproducing itself on the model of the past—a ‘speaking of the past’ (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity1993) that is a requirement of ceremonial efficacy (Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity, Schieffelin, Woolard and Kroskrity1998). It is the Tewa community deploying what Eisenlohr (Reference Eisenlohr2004) terms a distinctive regime of temporalization. Such regimes of temporalization, like the diasporic Hindu Mauritians he analyzes, or the Tewa described here, are in sharp contrast with the temporalization associated with Andersonian (Reference Anderson1991) linguistic nationalism and the ‘empty, homogenous, time’ associated with the future-orientation of modern nation-states. In contrast, the traditionalizing regimes construct an exemplary ancestral authority and evoke a unity of past and present and envisage a temporal process of replicated reproduction. Debenport captures this well in her discussion of paradoxical nostalgia: ‘Just as nostalgic discourses are not strictly about the past, hopeful discourses are not strictly about the future’ (Debenport Reference Debenport2015:112). Nostalgic discourses use the past as a model for action in the present and hopeful discourses, like the Tewa example here, approach an uncertain future with a preparation informed by the past.

This is not the ‘radical hope’ described by Lear (Reference Lear2006) in his interpretation of Crow people in the late nineteenth century, like Plenty Coups, meditating on a future after cataclysmic change. Tewa people do not know what the not-yet of the future will bring, but they are motivated to use their Indigenous traditions, including their distinctive language, in the present in order to bring about a future good life. Their hope is not radical since they are not so much leaping into a completely unknown future as moving into a rapidly changing world in a measured pace using resources that have served them well before, using ‘strategies undertaken on the terrain of language to repair past harm and, on that basis, to move forward to more equitable and peaceful futures’ (Heller & McElhinney Reference Heller and McElhinny2017:254–55). In contrast to a more radical hope, Tewa hope seems to be of the type identified by Tuck (Unangax) (Reference Tuck2009:417) as ‘generative’—a hope that is ‘involved with the not yet and, at times, with the not anymore… about longing, about a present that is enriched by the past and the future’. Tewa hope could also be described as ‘conservative’, rather than radical, since it is aimed at actions that would ensure they never have to confront a ‘not anymore’.

Hope: A coda

Though Bloch (Reference Bloch1986) and others have talked about hope in more universalist terms as if it were a translinguistic and transcultural category, I have followed Crapanzano in critiquing this perspective, a ‘mere’ hope—a relatively passive response— and in taking hope seriously ‘as a category of both experience and analysis’ (Crapanzano Reference Crapanzano2003:4). While there are clearly important universal features of hope such as its links to ‘opening’ time and creating a basis for motivation in the present for actions that might produce a better, future ‘good life’ (e.g. Antelius Reference Antelius2007; Mattingly Reference Mattingly2010), I think there are also benefits to exploring its linguistic and cultural variability and to view its operation within each distinct culture as a contingent ‘formation’ shaped by a particular historical trajectory and set of prevailing political economic structures. This may be especially true for Indigenous communities like the Tewa, where a hopeful anticipation of a better future involves decolonization and adaptive indigenization, where it involves heeding the moral call to work now, using cultural resources, to traditionalize a chaotic, complex, and rapidly transforming world.