INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is a life-stage like no other in terms of the ‘unequalled efflorescence of symbolic activity in all spheres’ (Eckert Reference Eckert2000:5), not least the sphere of linguistic variation. Researching the language of young people allows us to witness the negotiation, construction, and performance of emerging identities at a point at which many of the mechanisms behind these processes are being tested for the first time. Often, such research is carried out in mainstream high schools (e.g. Eckert Reference Eckert2000; Moore Reference Moore2003; Mendoza-Denton Reference Mendoza-Denton2008; Lawson Reference Lawson2009; Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2011; Kirkham Reference Kirkham2013), tracking and comparing the linguistic and social behaviour of different groups of students. In contrast, this article reports on a project that focuses on a particular group of young people from the outset—those who have been excluded from mainstream education for behavioural/disciplinary issues or because they find it difficult to adapt to the requirements of a mainstream school environment. The research took place in two learning centres in Manchester, UK, each catering for no more than fourteen students at any one time, thus providing a very different context to most school-based studies.

The focus here is on th-stopping, and the ways in which the feature is used to enact ‘street’ or ‘tough’ identities among particular individuals. I argue that th-stopping acquires this social meaning in this particular context in part through its association with grime (a UK music genre in which, like hip hop, the tough urban experience is central), and that it is the young people's involvement in grime-related social practices that allows them to draw upon it as a resource in this way. The article is structured as follows: first, I provide some background on th-stopping as a feature, looking briefly at its relationship with ethnicity and culture. I then touch upon the concept of multiethnolects, before positioning the study in relation to approaches to identity and ethnicity. This is followed by a description of the research context and the methods used, before reporting on the process of analysis and subsequent findings. The final section is split into two parts—a quantitative analysis of the data from all speakers, followed by a stance-based interactional analysis of some specific events involving a small selection of key individuals.

th-stopping in British English

th-stopping is being used here to refer specifically to the realisation of voiceless /θ/ as [t], with dh-stopping referring to the realisation of voiced /ð/ as [d]. Dh-stopping is much more widespread than th-stopping, occurring in any position, for example, them [dem], brother [ˈbrʌdə], with [wɪd], and in a wide range of varieties of British English including Liverpool (Watson Reference Watson2007) and London (Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill, & Torgersen Reference Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill and Torgersen2008). th-stopping can also occur in any position, for example, three [triː], birthday [ˈbɜːtdeɪ], youth [juːt]; however, it is much less frequent in British English, and is generally only found in quite specific varieties that originated elsewhere, such as West Indian Englishes and Creoles (e.g. Wells Reference Wells1982), Jamaican Creole (e.g. Cassidy Reference Cassidy1961), British Creole (e.g. Sebba Reference Sebba1993; Patrick Reference Patrick, Schneider, Burridge, Kortmann, Mesthrie and Upton2004), and Irish English (e.g. Hickey Reference Hickey2007). The notable exception is Liverpool English (e.g. Watson Reference Watson2007), although this, like its influencing Irish varieties (Honeybone Reference Honeybone, Grant and Grey2007), tends to quite clearly use the dental stop [t̪]. Perhaps due to its infrequent nature, I am not aware of any studies of th-stopping within the English varieties of the British Isles outside those of Liverpudlian and Irish. Where it is mentioned, it is done so in passing, or to make the point that it is not frequent (e.g. Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill and Torgersen2008:16; Dray & Sebba Reference Dray, Sebba, Hinrichs and Farquharson2011; Baranowski & Turton Reference Baranowski, Turton and Hickey2015:303).

th-stopping, ethnicity, culture, and music

The link between spoken language and ethnicity is complex, and variationist thinking on it has changed considerably over the years (see Fought Reference Fought, Chambers and Schilling2013 for an overview), with recent focus much more on the concept of ‘ethnolinguistic repertoires’ (Benor Reference Benor2010) rather than more bounded ethnolects. However, whether we see language as reflecting ethnicity or whether we see language as contributing to the social performance of ethnicity (which in turn is a facet of the performance of identity; see discussion below), the links between phonological features and particular ethnicities remain. th-stopping is associated with varieties of English that are associated with particular ethnic groups, for example, Chicano English (Mendoza-Denton Reference Mendoza-Denton2008), Polish American English (Newlin-Łukowicz Reference Newlin-Łukowicz2013), and, in particular, speakers of black varieties of English such as African American Vernacular English (Rickford Reference Rickford1999; Thomas Reference Thomas2007) and British Creole (Patrick Reference Patrick, Schneider, Burridge, Kortmann, Mesthrie and Upton2004).

However, the link between th-stopping and black cultures goes beyond the language varieties themselves and emerges in other social practices such as involvement with certain music genres. In the US, th/dh-stopping (primarily dh-) has been noted alongside other linguistic features as being part of Hip-Hop Nation Language (HHNL) (Alim Reference Alim2006) or Hip-Hop Speech Style (Cutler Reference Cutler1999, Reference Cutler2003). In these and other studies, hip hop is seen as being the story of the street, with a focus on the African American experience (Alim Reference Alim2006:122), and of life in the ‘hood’ (Pichler & Williams Reference Pichler and Williams2016:14) or ‘ghetto’ (Roth-Gordon Reference Roth-Gordon2009:65). Pichler & Williams (Reference Pichler and Williams2016) bring the study of HHNL to the UK, showing how a group of four young men use specific linguistic features to index cultural concepts (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2004) that serve to authenticate their identities in relation to hip-hop culture and what it represents.

Although hip hop is clearly relevant in the UK, there also exists a uniquely British style of rap in the form of grime, a music genre that developed in early 2000s East London, and one which, while sharing similarities with US hip hop, actually has its musical roots in UK garage, bashment, jungle, and dancehall. Alongside dancehall,Footnote 1 grime emerged out of black cultures (Drummond Reference Drummond2016), but unlike its musical cousin, it is arguably cross-racial (Dedman Reference Dedman2011:519). Linguistically, grime traditionally draws upon (and likely feeds and reinforces) Multicultural London English (MLE), that repertoire of features that has been documented over the last ten or so years in the capital city (e.g. Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox, & Torgersen Reference Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox and Torgersen2011). th/dh-stopping in general is prevalent in both MLE and in grime, but th-stopping specifically can be seen by glancing at some grime lyrics: “Grime is a road ting” (Bugzy Malone), “It's not a ting to draw the ting if you wanna swing” (Skepta), “That's a mad ting” (Lady Leshurr and many others), “Now you could get a box on some MMA ting” (Potter Payper). The fact that all of these examples are of the word ting is not coincidental, and is discussed later.

Multiethnolects

MLE constitutes a multiethnolect—the contested term (see Cheshire, Nortier, & Adger Reference Cheshire, Nortier and Adger2015 for a discussion) used to describe an ethnically neutral way of speaking that results from interaction between speakers from a wide variety of language backgrounds, as has occurred in various European urban centres. The project described here was carried out precisely with this concept in mind, with a view to exploring the value of identifying a possible Multicultural Urban British English (MUBE) as an overarching version of MLE (e.g. Drummond Reference Drummond2017, Reference Drummond, Braber and Jansen2018). Pichler & Williams’ (Reference Pichler and Williams2016:6) London based study reported the problems of distinguishing specific linguistic features as either being part of HHNL or as being part of everyday MLE, as there is considerable overlap between the two repertoires. The same overlap undoubtedly exists in the context being described here; however, I do not see it as problematic, due to the fact mentioned above, that MLE (or a possible MUBE) is generally seen as being the language of grime (Green Reference Green and Coleman2014:68). Moreover, the type of contextually dependent variation under investigation here clearly fits within the ‘stylistic practice’ understanding of the concept of multiethnolects (Svendsen & Quist Reference Svendsen, Quist, Quist and Svendsen2010).

Language, identity, and stance

Fundamental to both this study and the third-wave variationist approach it espouses is the understanding that ‘[linguistic] variation is not just a reflection of the social, but essential to its construction’ (Eckert Reference Eckert and Coupland2016:70). In fact, I would go further than this and suggest that variation (and indeed language) cannot reflect anything due to the fact that it itself is constructing and enacting the very realities we perceive. As soon as we talk of one thing reflecting another, we are setting up a situation in which there is separation between the two, as if there is an external something—be that a social hierarchy, an identity, a reality—whose characteristics are able to be represented and reflected in part through language. Rather, identities are created in context; they are ‘the outcome of social practice and social interaction’ (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2011:1). Yet in order to study this effectively, we should not rely on interaction alone. Bucholtz & Hall (Reference Bucholtz, Hall, Llamas and Watt2010:19) make the point that ‘identity does not emerge at a single analytic level… but operates at multiple levels simultaneously’. It is through interaction that individual features acquire social meaning, but it is through language contact and other mechanisms that the features are available to be used in the first place. Bucholtz & Hall (Reference Bucholtz, Hall, Llamas and Watt2010:19–25) discuss their five principles that they see as fundamental to the study of identity (see also Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2005). Although all are relevant, three in particular speak directly to the approach taken here.

• The emergence principle. Identity is best viewed as the emergent product rather than the pre-existing source of linguistic and other semiotic practices and therefore as fundamentally a social and cultural phenomenon.

• The positionality principle. Identities encompass (a) macrolevel demographic categories; (b) local, ethnographically specific cultural positions; and (c) temporary and interactionally specific stances and participant roles.

• The partialness principle. Any given construction of identity may be in part deliberate and intentional, in part habitual and hence often less than fully conscious, in part an outcome of interactional negotiation and contestation, in part an outcome of others’ perceptions and representations, and in part an effect of larger ideological processes and material structures that may become relevant to interaction. It is therefore constantly shifting both as interaction unfolds and across discourse contexts.

The focus here, therefore, is very much on the (social) practices in which the young people engage, as it is within these that realities are enacted and performed. Relevant to this approach is the fact that social meaning does not reside in individual linguistic variables, but rather in the clustering of these variables along with other nonlinguistic symbolic resources. Within studies of language variation, uncovering the social meaning of these clusters usually takes the form of investigating either style (e.g. Eckert Reference Eckert2000; Moore Reference Moore, Maguire and McMahon2011) or stance (e.g. Ochs Reference Ochs, Duranti and Goodwin1992; Rauniomaa Reference Rauniomaa2003; Kiesling Reference Kiesling2009), or a combination of the two (e.g. Eckert Reference Eckert2008; Moore & Podesva Reference Moore and Podesva2009).

Stancetaking is a useful framework within which to view language variation, social meaning, and concepts of style (e.g. Jaffe Reference Jaffe2009, Reference Jaffe and Coupland2016; Kiesling Reference Kiesling2009). Stance here refers to ‘the processes by which speakers use language (along with other semiotic resources) to position themselves and others, draw social boundaries, and lay claim to particular statuses, knowledge and authority in ongoing interaction’ (Snell Reference Snell2010:631). Kiesling (Reference Kiesling2009) shows how a stance-based approach complements existing variationist views by demonstrating how they are, in many ways, talking about the same ideas using slightly different terminology. Where ‘the Stanford group’, as Kiesling refers to them (e.g. Eckert Reference Eckert2000; Benor Reference Benor, Sanchez and Johnson2001; Zhang Reference Zhang2005; Podesva Reference Robert2007; Mendoza-Denton Reference Mendoza-Denton2008), discusses personal styles and personae, Kiesling sees these styles as repertoires of stances (Reference Kiesling2009:178). Similarly, when Schilling-Estes (Reference Schilling-Estes1998) refers to the roles conversational participants play within interaction, this too is stance. The present study takes the uncontroversial position that stance and style can operate within the same overarching theoretical framework, and this framework is the basis for the interactional analysis later.

Of interest in the discussion surrounding variability of social meaning in relation to linguistic variation is the extent to which speaker intent plays a part. Eckert (Reference Eckert and Coupland2016) questions the emphasis on the conscious/unconscious distinction (in terms of how aware a speaker is of a particular variable or variant) found in first-wave variationist ideas, pointing out how difficult it is to distinguish between the two anyway. She goes on to suggest that ‘agency does not equal or require awareness’ (Reference Eckert and Coupland2016:78), explaining how the social meaning of variables can be understood and utilised at a very unconscious level. Similarly, Bucholtz & Hall (Reference Bucholtz, Hall, Llamas and Watt2010:26) make the point that ‘habitual actions accomplished below the level of conscious awareness act upon the world no less than those carried out deliberately’. In other words, all actions have a role in the performance of identity, be they intentional or unintentional, conscious or unconscious. Often it makes little difference whether particular features/actions are intentional or not, although in cases where it is possible to identify intent, doing so can add additional insights into particular interactions, as I demonstrate later.

Ethnicity

I am approaching the concept of ethnicity from within the view of identity described above, and on the understanding that although I separate it at one stage of the analytic process as a way of exploring a possible effect, it makes little sense to view any aspect of identity as independent of any other (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2011:2). I am specifically distancing myself from the idea of ethnicity being a meaningful mechanism by which to pregroup individuals in this kind of study (or any kind of study of social life; see for example Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004). This is nothing new (see for example Mendoza-Denton Reference Mendoza-Denton2008; Madsen Reference Madsen2013; Kirkham Reference Kirkham2015) but it does need to be stated, as much variationist work has tended to inflexibly group people in this way almost by default. As with any other aspect of identity, ethnicity is treated as being of interest if it emerges as something being enacted within particular interactions or across particular contexts. I do provide (largely) self-reported ethnicities for each individual, but I do this partly in order to then challenge the assumptions that such a blunt, nonintersectional, macro approach makes. By taking the focus away from ethnicity as something separate and discretely measurable, I am trying to align the study alongside work such as Rampton (Reference Rampton2011), Madsen (Reference Madsen2013), and Kirkham (Reference Kirkham2015). Unlike these studies, however, there is not a refocusing onto issues around social class, for reasons I discuss shortly.

THE STUDY

Context

The UrBEn-ID (Urban British English and Identity) project was a two-year study (July 2014–July 2016) funded by The Leverhulme Trust, which explored the use of language and other semiotic practices in the enactment of identities among fourteen to sixteen year olds in inner city Manchester. The ethnographic part of the study took place in the academic year 2014–15. The project's two main research sites were inner-city learning centres within the Manchester Secondary Pupil Referral Unit (PRU), which cater for years ten and eleven (aged fourteen to sixteen) students who have been permanently excluded from mainstream education. The young people must attend every day during normal school hours (9.00–3.00), and study a reduced curriculum of core subjects for GCSE.Footnote 2 By definition, all of the pupils in the learning centres have issues of one kind or another with the school context, hence they have ended up where they are—separated from mainstream with very little chance of returning.Footnote 3 The reasons for their exclusion varied widely—from fights, to bullying, to confrontations or aggression towards teachers and school staff, to general and persistent more minor discipline issues, often brought about by an inability to adapt to the mainstream environment. Many times we never knew the reasons for exclusion as we never asked; we just listened if they wanted to tell us. In addition (and perhaps not unrelatedly) to their volatile experiences with the school system, many of the young people had unstable family lives. Again, we did not ask, but the information we gathered either from the young people themselves or from the staff suggested a variety of home life experiences ranging from difficult to traumatic.

The centres are staffed by a variety of people. Each has two coordinators who are in charge of the day-to-day running of the centre and who usually have some kind of youth work background. In addition to being in charge of the centre, the coordinators sit in on classes as additional support for the subject teacher. The subject teachers work on a peripatetic basis—moving between centres to deliver classes in the core curriculum subjects of English, math, science, and art. There are additional classes in Preparation for Working Life (PfWL) and Personal Social and Health Education (PSHE), the first of which is delivered by a specialist teacher, the second by one of the coordinators. The final key staff member is the youth worker—a permanent member of the staff in each centre who offers general support in and out of classes. Due to the small and enclosed nature of the environment, there is a real sense of everybody pitching in. Meals are prepared by whichever staff members are keen and capable, be that coordinators, youth workers, or even caretakers, and staff roles seem very fluid, at least to an outsider. In between classes, pupils are generally free to play pool, table tennis, watch TV (usually music videos), or go outside and smoke. At one of the centres they are also free to go to the local shop, although they are supposed to let staff know they are going. At the other centre the shop is further away and they are not allowed to go there.

The result of all of this is a lively, often very noisy environment in which young people are free to express emotions, disagreements, and their own individual personalities within the enforced boundaries of fairness and awareness of others. Arguments (often extremely intense) are frequent, although physical fights are rare. Battles between staff and students are everyday occurrences, often involving the same individuals. Attendance was patchy, although often predictable on an individual basis, with some rarely missing a day, and others turning up only occasionally.

The participants

The twenty-five participants discussed here all attended one of the two centres over the course of our time there. Some were present throughout the period, others were more transitory. Some were previously known to me due to a pilot study I carried out at the same locations the previous year. Table 1 provides pseudonyms, sex, centre, year group, and ethnicities of the participants. Ethnicities were established through a combination of self-reporting and staff-reporting. Social class was never a focus of the project, as the participants represent a uniform sample in terms of social background and educational expectations and attainment. This is not to say that class is not relevant, simply that there was no meaningful social variation, meaning that the study is, by default, one of this particular socioeconomic group. The PRU population in general tends to represent the lower end of the socioeconomic scale, with pupils known to be eligible for and claiming free school meals (indicating low-income families) being around four times more likely to receive a permanent or fixed-term exclusion than those who are not eligible (Department for Education 2016). As far as I know, all participants were born and raised in the UK, the vast majority in Manchester.

Table 1. Participants.

METHODS

Two researchers (the author and a research associate, Susan Dray) spent the 2014–15 academic year involved in the day-to-day practices of the two centres. We collected detailed fieldnotes and audio recordings whenever the opportunity arose. Fieldnotes were gathered through observation and participation in activities both in and out of class. It was often possible to make brief notes at the time, but full notes were written up in detail that evening or the following day in the form of a field diary. A variety of audio recordings were made, including spontaneous interactions in and out of class; interviews/conversations between individuals or small groups of young people and one researcher; peer or self-recording by the young people, often while outside smoking; mock-interviews while preparing for college applications; and discussions of words we heard the young people use. Recordings were made on Zoom H2 and Zoom H1 recorders. All of this resulted in 413,000 words of fieldnotes and seventy hours of audio recordings. Overall consent for our research activities in the centres was established from the outset from the head of the PRU, the centre staff, and the young people. We also asked for specific permission each time we introduced the voice recorder.

We did face some practical issues, however. Throughout our time in the centres we were very aware that we were visitors in their world, and that without the cooperation of both the young people and the staff there simply was no project. In actual fact, we had almost full cooperation from all members of staff, who were happy to have us participate in and observe whatever we wanted (unless there was a specific issue of privacy or sensitivity) and mixed cooperation from the young people. At first, some were understandably wary of us and could not understand why we were there. But over time, they got used to (and at times even enjoyed) us hanging around and interacting with them. Our requests to record what was going on gradually became routinely granted, with several individuals keen to take the opportunity to gather some additional data by taking charge of the audio recorders. But there were times when the young people did not cooperate, and simply refused to participate. On other occasions the individuals we needed just were not there, having not turned up that morning, or having been temporarily excluded for an incident earlier that day or that week, or having simply left for another centre at short notice due to some change in circumstances. All in all, the PRU is a challenging, unpredictable, yet endlessly fascinating and rewarding environment in which to be involved.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Quantitative analysis

The data presented here represent a mixture of recording contexts; where possible, however, each speaker's total includes at least some data from a ‘research meeting’—a conversation/interview with one of the two researchers in which the young people were either alone or in pairs. The purpose of this was to try to ensure at least some sense of comparability, albeit in a limited way. Data collected from the mock college interviews were excluded on the basis of this being a very different context in which only a few participants were involved. Not all of the data we recorded are suitable for this type of phonetic analysis, so what is presented here represents a large sample of the total. As the analysis progresses throughout this section, the data set is made more specific and is reduced. Table 2 provides a contextualising overview by showing the results of the auditory analysis of all 886 tokens of (th) from the speech of twenty-five participants. This represents a mean rate of just over thirty-four tokens per speaker; however, there is some variation in the total for each individual, mainly due to the methodological issues mentioned above (attendance, cooperation, etc.).

Table 2. Overall results of the auditory analysis for (th).

Preliminary auditory analysis of the (th) variable was carried out at the time of transcription of the audio recordings using Elan. The transcriber was one of the two researchers or one of five employed transcribers; they highlighted some of the more obvious variants as they occurred. More careful auditory analysis was then carried out by me to check those tokens already identified, and to identify all other instances of the variable. Tokens that were unclear even after repeated listening due to poor recording quality or overlapping speech were marked as such and discarded from further analysis. The only other issue that emerged in the process was the difficulty in discriminating between [f] and [θ] on occasions. Sometimes it was clearly one or the other, but other times the two were almost indistinguishable. Here the field notes and prolonged observation helped, as both researchers had noted several times in our day-to-day observations the almost complete absence of [θ] in the speech of any of the participants (the difference is, of course, much easier to distinguish with additional visual cues). As a result, I was predisposed to identifying genuinely in-between tokens as [f]. This would be potentially problematic in a study of th-fronting specifically, but as the main focus here is on th-stopping, I feel satisfied with the process.

All speakers

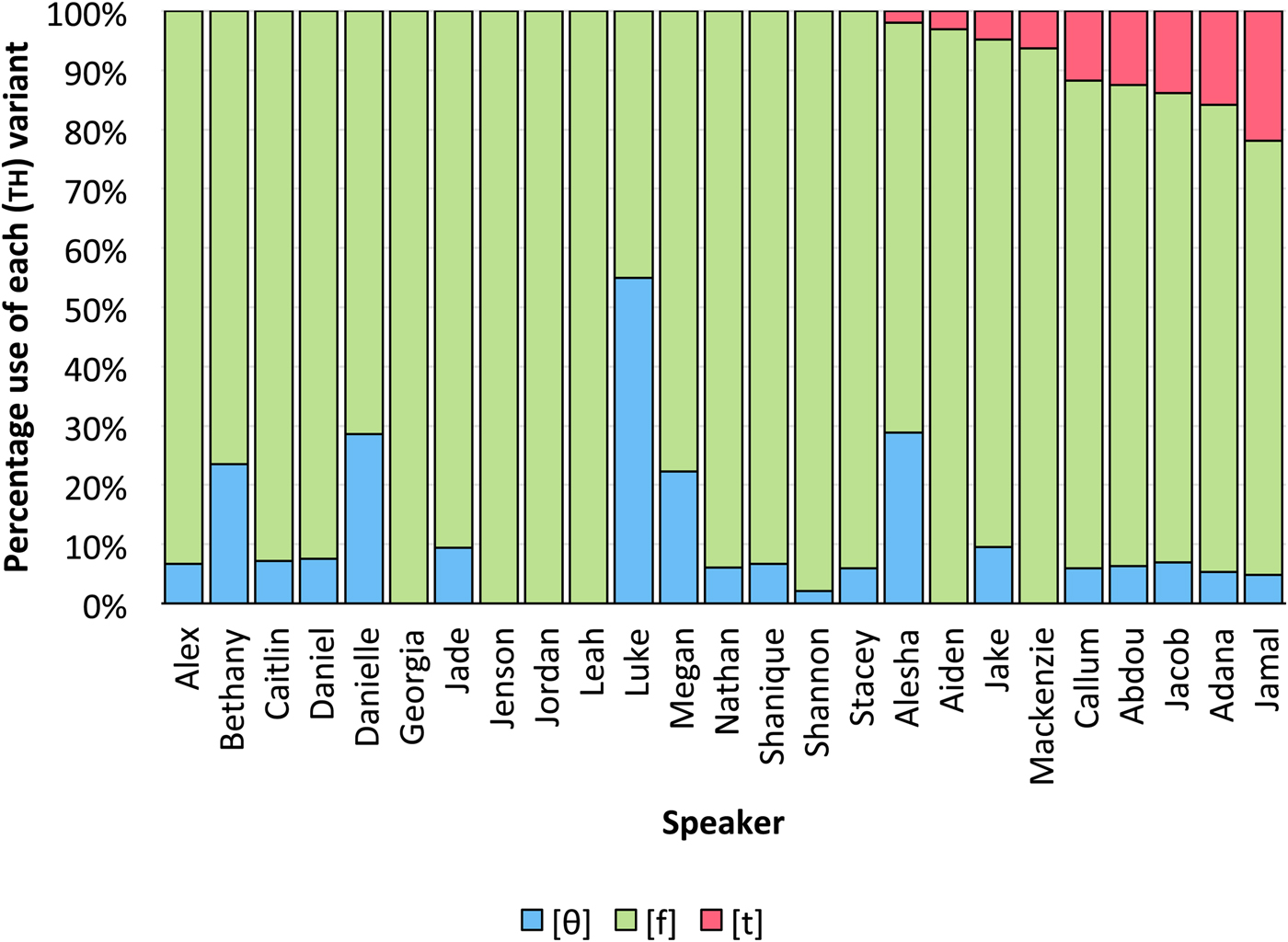

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 819 [θ, f, t] (th) tokens among twenty-five speakers, ordered from the right by frequency of [t]. [h] and [ʔ] tokens have been removed due to very small numbers and limited obvious relevance to the analysis, as have tokens that were unclear. Two things immediately stand out from the chart: (i) that fronted [f] is by far the most frequent variant among the group as a whole, accounting for almost 85% of the total and 100% of the tokens for five of the speakers; and (ii) use of [t] is very limited, both in terms of overall frequency (5% of the total) and in terms of distribution among speakers (eight of twenty-five).

Figure 1. Distribution of the 819 [θ, f, t] (th) tokens, ordered from the right by frequency of [t] (twenty-five speakers).

Multiple logistic regression analyses were carried out using Rbrul (Johnson Reference Johnson2016), including individual speaker as a random effect. Rbrul is a variable rule program in the mould of Goldvarb (Sankoff, Tagliamonte, & Smith Reference Sankoff, Tagliamonte and Smith2005), yet which incorporates mixed-effects modelling. The result is a model which ‘can still capture external effects, but only when they are strong enough to rise above the inter-speaker variation’ (Johnson Reference Johnson2009:365). Rbrul expresses coefficients in log-odds rather than factor weights, although both are given in the analysis presented here. The first analysis was carried out on the data presented in Figure 1, except that those speakers with fewer than ten tokens (Danielle, Jenson, Megan) were excluded. These exclusions resulted in 800 tokens from twenty-two speakers being entered into the model, with thirty-five realisations of [t]. The dependent variable was (th) with the application value as [t] and the nonapplication values as [f] and [θ]. The independent variables are described in Table 3. Each independent variable was included based on the plausibility of it playing some kind of role in the observed variation, informed by previous studies or by experience of the context. The results of the analysis can be seen in Table 4. It should be pointed out that two of the tokens in particular are ones that might normally be excluded from traditional quantitative variationist analysis on the basis of their context of use not being natural to the speaker. Both were used in the process of describing someone else's speech, so in that sense they did not ‘belong’ to the speaker using them. However, this highlights a problem with traditional variationist research, as it begs the question of where to draw the line. Yes, these examples are clearly not occurring as a natural part of these speakers’ repertoires (at least not in these instances), but excluding them necessitates the implementation of a cut-off point for other less clear examples. Rather than get into a situation whereby the researcher decides what is and is not ‘natural’ for a particular individual, I am taking the approach that all language is data, and if it occurred, it is part of the linguistically constructed reality of that moment.

Table 3. Independent variables for the regression analysis.

Table 4. Regression analysis (Rbrul) of the effect of linguistic and social factors on the realisation of voiceless (th)—twenty-two speakers with > ten tokens.

Before looking at the statistically significant variables, it is perhaps worth looking, in particular, at one of those that did not reach statistical significance in this model: ethnicity. Ethnicity is of particular interest here, as it of course relates to points made earlier with regard to the links between th-stopping and black varieties of English. However, ethnicity does not emerge as a statistically significant influence on the realisation of /θ/ as [t]. It would be easy to simply state this fact and move on; however, there is clearly a correlation between ethnicity and use of [t], even if it is not strong enough to emerge as significant among the other variables. As can be seen in Table 5, the percentage of [t] realisations among white British speakers is considerably lower than almost all the other ethnic groups, and if we were to take a very blunt ‘white’ vs. ‘not white’ approach, the difference would be very large indeed. While this approach is fairly common in variationist studies, it rarely explains anything in itself. This is not to say there is no value in it at all—looking for correlations such as these then opens the door to investigating why they might be occurring, but in themselves they do not carry much meaning (cf. Cameron's Reference Cameron, Joseph and Taylor1990 ‘correlation fallacy’). After all, ethnicity itself is such a fluid concept that is constructed in practice rather than something passively inhabited (e.g. Schilling-Estes Reference Schilling-Estes2004), so unless one looks at how it is being constructed, a simple measurement offers limited insights. In addition, straightforward correlations (and statistical analyses such as the ones above) miss the important fact that in this particular case, three White British speakers did use [t], and two Mixed White/Black Caribbean or Black Caribbean speakers did not. Admittedly, when we are talking about such large data sets as can be found in a lot of first wave variationist studies (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1972) in which such correlations are central, these kinds of outliers are perhaps of little relevance; after all, the aims of such studies, especially in relation to issues of identity, tend to be very different (see Drummond & Schleef Reference Drummond, Schleef and Preece2016 for a discussion). But in a smaller-scale study such as this, a single instance of a variant can, arguably, provide a lot of information: ‘Indexical meaning can… arise out of statistical commonality or single instances of use that are salient enough to gain meaning for speakers’ (Kiesling Reference Kiesling2009:177). But this observation works both ways—on the one hand, the existence of these outliers warns us against drawing blunt ethnicity-related conclusions, but, on the other, we do still need to account for the fact that the rest of the speakers did fall into such a pattern. One possibility is that ethnicity is playing a more indirect role, perhaps mediated by another social factor (or combination of factors). This idea is explored shortly.

Table 5. Use of [t, f, θ] divided by speaker ethnicity. Percentages show proportion of total tokens for that group.

With regard to those factors that did emerge as statistically significant, the models suggest that informal contexts are more likely to generate realisations of [t] than formal contexts (research meetings). In fact, only four of the thirty-five [t] tokens appeared in a formal context. While this is perhaps not surprising, it is of some interest in that it reinforces the observed similarities between the various informal contexts. For example, this category groups together the lessons themselves and the breaks between lessons, two situations that might usually be seen as something quite different in a ‘normal’ school environment. But this is not a ‘normal’ school environment—classes are very small (could be anything from one to seven pupils) and the atmosphere is very relaxed. So-called banter between students (see Dray Reference Dray2017) is as common in the classroom as it is outside, and while they may be pulled up for excessive swearing, for example, in class, the same can happen outside class. However, when we invited individuals or pairs to come and talk to us separately, however informal we made it, this was still an unfamiliar and relatively new situation for them, and one that tended to inhibit use of [t]. The possible reasons for this are explored in the next section.

The raps factor is of interest as it begins to identify a possible social practice aspect of the variation rather than a macro-social influence. All it suggests at this stage is that those individuals who we observed rapping as part of their everyday practice (Abdou, Aiden, Callum, Georgia, Jacob, Jamal) are more likely to use a [t] variant. Crucially, however, only two of the recorded tokens of [t] being discussed here occurred during rapping; the rest occurred as part of ‘normal’ speech. Position is of passing interest, but is largely predictable, given that thirty of the thirty-five instances of [t] occur in word initial position. It is also interesting to note that of the six individuals who we observed rapping, three are white British, one is Black African, one is mixed white British/black Caribbean, and one is mixed white British/Pakistani. The reason this is important is that in a study with a larger sample it might be expected that the traditional association of rap/grime with black culture results in a greater likelihood of ‘rappers’ being nonwhite. In this case, ethnicity might emerge as a statistically significant factor alongside rapping, or else the argument could be made that ethnicity is being mediated by rap, thus still playing a role. I cannot discount this interpretation, and it potentially brings in useful discussion around what resources are available to be used by, and how ethnicity can be enacted differently within, different groups of people. However, the data that is available here do not allow that investigation in any meaningful way.

With raps emerging as significant, it might seem strange that music does not do the same. However, I think this is more to do with the way in which we coded the data for musical tastes. If we had our time with the young people again we would delve more deeply into this, but the reality is that our knowledge is limited and patchy in this area. The categories we used are vague and overlapping, and we did not manage to gather information consistently. Rapping is far more robust, as this is a straightforward measure of an observed activity.

A further model was tested including only the nine individuals who had produced [t] (342 tokens in all) and this time the only two factors emerging as statistically significant were again formality and position (see Table 6).

Table 6. Regression analysis (Rbrul) of the effect of linguistic and social factors on the realisation of voiceless (th)—nine speakers who produced [t].

One final point should be made in relation to the more quantitative aspect of the study—the fact that [t] appeared only in a very limited set of lexical items (thing x 23, thief x 5; everything x 2; three x 2; birthday x 1; teeth x 1; anything x 1). Although lexical context was excluded from the model on the basis of the distribution of the variants being so skewed between the items, it is of course of interest that only certain words appear able to use [t]. Clearly the most frequent context is thing, which is perhaps no surprise when we consider the grime lyrics from earlier. In fact, it would be plausible, and in many ways more robust from a quantitative perspective, for this whole study simply to focus on variation within thing. Footnote 4 With that in mind, one final model was tested that included only thing related words (thing, anything, everything) that were realised as [θ, f, t]. Individuals with fewer than five tokens were excluded. The results can be seen in Table 7. Interestingly, the only factor that emerges as statistically significant this time is raps.

Table 7. Regression analysis (Rbrul) of the effect of linguistic and social factors on the realisation of voiceless (th)—only thing words.

Clearly none of the models can fully explain the situation, as each is necessarily partial and limited in its own way; with such small numbers (thirty-five instances of [t] overall) and with such skewed data, we should be cautious about reading too much into them. Also, by inputting raps as an influencing factor, we are in danger of simply substituting ‘practice’ categories for macro-social categories. Taken as a whole, however, the results above do serve a purpose in that they provide insights into some possible patterns, highlighting areas that perhaps warrant further investigation. Clearly there is something about both being in an informal context, and being someone who raps, that predisposes an individual to produce [t], even taking into account the limited lexical range in which such variation is possible. In addition, it would appear that straightforward ethnicity is not a relevant explanatory category to pursue. But at the moment these remain abstract and somewhat meaningless correlations. In order to gain insights into what these patterns might mean, we turn to the interactional data below, which highlights two specific contexts.

Interactional analysis

One context that plays a significant role in the data here is the weekly art lessons in one of the centres. These are generally very laid-back sessions, lasting longer than normal lessons (over two hours), with a teacher who enjoys engaging with the class in casual conversation as they are working, and an extremely experienced youth worker, Michael, who is well-respected and who relates to the young people especially well. The class contains four of the [t] producers, and the context (over various recordings) accounts for nineteen of the thirty-five tokens of [t].

The four individuals under discussion could loosely be described as friends within the context. Jamal is undoubtedly the ‘leader’, as is evident from the behaviour of the others around him. Casually but immaculately dressed in either sweatpants or jeans and t-shirts, Jamal is slim and quite small compared to the others, although he carries himself with apparent confidence, at least to an observer. Jacob is a sportsman—he is well-built and physically fit, and often talks of his physical/sporting activities. He is viewed by the others as a bit of a joker,Footnote 5 and dresses casually in sweatpants and t-shirts. Abdou, throughout our time in the centres, appeared to constantly seek Jamal's approval, with Jamal in turn mocking him at almost every opportunity. Often the target of the mocking was Abdou's appearance, with Jamal regularly describing him as “ug” (‘ugly’). Abdou seems to put up with a lot of abuse (mostly verbal but occasionally physical) but keeps coming back for more. Jake is the outsider of the group—coming from a different part of Manchester, he would rarely see the other boys outside school. He is bigger than the others, but not toned like Jacob.

Topics of conversation in the art class tend to be quite wide-ranging; however, a recurring theme is one of ‘toughness’, be that fights the boys have either had or witnessed, getting into trouble with the police, or demonstrating how friendly they are with known criminals or possible gang members. Extract (1) took place during a conversation in which all four boys were present, along with Michael, the youth worker (aged around fifty). Also in the room were one of the girls, Shanique, one of the centre coordinators, Joy, and me. However, Michael and the four boys were sitting together, with everybody else outside of this small group. They were working on mosaics—which at this moment meant arranging cut-up images onto a page. The conversation leading up to the extract was about somebody (let's call him Marcus) they all knew who was in prison, and when he was getting out. Here, they are discussing when they last saw him.Footnote 6

(1)

Abdou is the first to use a [t] variant in line 20 when he is talking about Marcus being a “tief”. The reason this is of interest is because up until this point in the recording, Abdou had produced nineteen tokens of voiceless /θ/, sixteen of which were realised as the ubiquitous [f], and three as [θ]. Incidentally, all three [θ] tokens occurred while he was singing as he worked, so it is likely that he was simply replicating the standard variant within the original version of the song itself. Jacob produces a similar realisation of the same word in line 22, having previously produced eleven tokens of voiceless (th) comprising seven [f], three [θ] and one [t]. So what is it that brings about Abdou's use of [t] at this particular point?

I think there are two plausible (related) explanations. Firstly, from a stance-based perspective, Abdou and the others are clearly setting themselves up as being part of this tough, criminal life. There has already been talk of when each person last saw Marcus, thus establishing their credentials as being close to that world. They are not necessarily trying to outdo each other, but they are each trying to lay claim to at least being in close proximity to Marcus. Abdou and Jamal are slightly ahead here given the fact that Marcus was actually with them on the bus (line 1), and they were all part of whatever misdemeanour is mentioned by Jamal (unfortunately unclear) which led them all to “run for it” (lines 5–7). Jamal then lays special claim to being close to Marcus by emphasising that Marcus used to chill with him and not Lamar (line 15). Abdou then delights in recalling when Marcus robbed “Lamar's” (presumably Lamar's house) which is when he says that he used to be a “tief”, a sentiment then echoed by Jacob. It could be argued that the use of [t] is one element of the style Abdou is creating and manipulating in the context of ‘tough-talk’. In using [t] in this environment, Abdou is reinforcing the stance he is taking in which he is trying to align himself alongside Marcus as an insider to this world. He has already provided his credentials as being a friend of Marcus, and now he is reminiscing (in a very positive way—there is laughter in his voice) about his criminality. In order for this interpretation to work, there must of course be something indexically linking [t] to a stance of toughness. I return to this shortly.

An alternative explanation calls on lexical rather than phonetic variation. The fact is, of the five examples of the word thief we have analysed in the recordings, all are realised with the [t] variant. Although impossible to say for sure with such a small sample, there is a possibility that thief and tief are seen as two distinct words with slight differences, if not in referential meaning, then at least in contextual appropriateness. The difference is subtle, but such an interpretation renders this less an instance of th-stopping and more one of lexical choice. This interpretation is supported by the fact that in line 23 Michael, the adult youth worker, also uses the [t] variant. Although this is specifically not a study of the adults’ speech, the language of the adults as interlocutors is of course relevant, as it forms part of the interactionally created reality. There is no reason to suspect that Michael was aligning himself alongside Abdou and the others in terms of their positive stance towards the world of criminality; rather, his use of tief was a predictable lexical choice given his own Jamaican heritage and very noticeable Jamaican English dialect and accent, an accent that very much includes variants of /θ/ as [θ, t] (Wells Reference Wells1982:565) (although not [f], which indeed is a variant I did not hear Michael use). In this sense, tief simply is the Jamaican English word for thief, so this is the natural word for Michael to use. For the boys, however, there is no such natural explanation; the boys do not have Jamaican English dialects.

There is a possibility that the increased use of [t] in this context comes about as a result of the boys accommodating towards Michael's speech. I cannot dismiss this interpretation, as Michael is present in the majority of the art lessons (the situation in which most of the recorded th-stopping occurs). If this were the case, however, I would have expected a lot more th-stopping to emerge in other situations, as Michael is with the boys most of the time in one way or another. But this does not appear to happen, either in the recorded or observed data. The interpretation is therefore not impossible, and it might be the case that individual instances can be reliably interpreted as coming about in this way, but it is an unlikely explanation of the overall pattern. There is also a strong possibility that there is a priming effect in operation—that one use of [t] in a particular context encourages a repeated use. Although this is likely, however, I would argue that it does not detract from the stance-taking interpretation. It may lower the bar for the availability of [t] to be used, but its use is certainly not inevitable, and this would not explain its initial use.

The boys are choosing (for want of a better word, see earlier discussion surrounding the conscious/unconscious distinction) to use this particular variant. At which point, the distinction between the two explanations (lexical or phonetic) largely ceases to be relevant, as the question simply becomes—what is the indexical link between a stance of toughness and either tief or [t] in the speech of the boys? I believe one possibility lies in the cultural associations of th-stopping in relation to music. Recall that raps emerged as statistically significant in the model, suggesting that those individuals who we observed rapping were more likely to produce [t]. In fact, three of the four the boys here (Abdou, Jamal, Jacob) and both of the th-stoppers are ‘rappers’. But we are talking about a specific type of rap—that practiced in UK grime and Jamaican dancehall. Grime especially is very down to earth, and very much of the street. It is the story of hardship, of disenfranchisement, of the daily battles faced by what many see as the UK's underclass (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2008). Grime belongs to the poverty-stricken inner city, and while it crosses racial divides, it is socially grounded in a particular social class (Dedman Reference Dedman2011:519). Grime is tough. And most importantly, grime speaks to urban British youth in the language of urban British youth, and its participatory nature thus sets up a cycle of linguistic reinforcement. Grime (and, to an extent, dancehall) is not a type of music that people passively listen to, it is a type of music they engage with (Dedman Reference Dedman2011, Drummond Reference Drummond2016). Its history is one of young men creating homemade tapes of themselves rapping, and this DIY approach has continued; the tapes have simply been replaced by phone videos and YouTube. The fact that we observed these young men rapping in our day-to-day attendance at the learning centres is crucial; it helps to demonstrate how embedded the music is in everyday life. We have several examples of boys (including Jamal and Abdou) seamlessly slipping into rap as part of a conversational interaction, as if the lines between their ‘normal’ conversational speech and their ‘grime’ speech are blurred or even nonexistent.

I am wary of overstating the specific grime significance here, as many of the characteristics and social connections described above are equally relevant to hip hop more widely (e.g. Cutler Reference Cutler1999; Alim Reference Alim2006; Alim, Ibrahim, & Pennycook Reference Alim, Ibrahim and Pennycook2009; Quinn Reference Quinn2010; Jeffries Reference Jeffries2011). However, I would suggest that the especially immersive nature of grime sets the findings from this study apart from apparently similar studies such as Cutler (Reference Cutler1999), which looks in great detail at ‘Mike’ and his use of AAVE features partly as a result of his alignment with hip hop (see also Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2011). While there are many comparisons to be drawn, especially in relation to the lifestyle Mike became part of, I would argue that listening to, and learning lyrics of, well known hip-hop tracks (as Mike did) is subtly yet crucially different from actually engaging with the production of grime.

In summary, what I am arguing here is that the boys are using this particular variant in the process of adopting a stance of toughness in relation to the interaction that is taking place. The variant acquires this social meaning in this particular context through its association with grime (and rap/hip hop and dancehall more generally), which embodies a street/urban/tough lifestyle. The quantitative analysis gave a partial picture by highlighting the possible connection between use of [t] and ‘rapping’, and this then formed a basis for the interactional analysis.

However, it is not always the case that [t] is used so explicitly to align with a tough stance in relation to the content of the particular interaction taking place. It can also be used more generally to index participation (or desired participation) in that world of grime, especially when such involvement does not perhaps come quite so naturally. Callum is very different to Jamal and his friends. At the other centre, he is an energetic and generally cheerful boy who, although seemingly confident, does not appear to have the swagger or coolness of Jamal especially. Callum is white, interested in grime, and we have observed him rap. In the thirty-four tokens of /θ/ we have recorded of him, twenty-eight are [f], four are [t] and two are [θ]. Two of the instances of [t] come close together in a recording made, again, during an art lesson. Interestingly, grime had itself been the topic of conversation moments before the extracts below, with Callum actually rapping in class and then talking about one of his favourite artists. In extract (2), Callum is wandering around the room, and seems to be looking for the voice recorder.

(2) Callum: yo where's that little recorder thing <[tɪŋ]>?

When he finds it he says:

(3) Callum: yo this th-<[f]>- this thing's <[tɪŋz]> still on.

Extract (3) is very telling, as Callum self-corrects from fing to ting, an apparently conscious move. This correction arguably illustrates the role of intent discussed earlier; neither of the identities that Callum performs before and after the self-correction of this contextually salient variable is any less real than the other, yet the second one is the one he intended to perform at that particular moment. By consciously using a particular variant, Callum is taking a stance in an attempt to (re)align himself as someone involved in grime and all it represents. Without that self-correction, we are glimpsing another side of Callum—the side that he likely performs in other contexts, and, arguably, the side that comes most naturally to him given the social constraints of his particular life experience. It is almost as if for a second he forgot the identity he was performing at that moment, and consciously re-adopted his preferred stance in relation to the grime lifestyle. Perhaps [t] is an example of a feature that at the moment remains conscious and awkwardly intentional, yet one that, in time, will become automatic and more integrated into his own style (Eckert Reference Eckert and Coupland2016:78). This scenario brings to mind an incident described in Cutler (Reference Cutler1999:429) when Mike, a white teenager who uses AAVE speech features as part of his increasing identification with hip-hop culture, self-corrects his standard pronunciation of [æsk] to the more desirable AAVE version of [æks]. A similar occurrence is described in Bucholtz (Reference Bucholtz2011:34) when she suspects a young male speaker is ‘correcting away from Standard English’ in his use of remote past been. Arguably, Callum's need to perform this identity at this point was made especially acute due to an incident that had occurred a few minutes previously (extract (4)), just after he had been rapping. Having heard him rap, the teacher (James) asked him what it was. Also present are Mark, an IT support teacher, and Adana, a girl in the class.

(4)

The reason this exchange was funny for the staff was that Brixton and Buxton are two very different places to get mixed up. Brixton, in South London, has a reputation for being a tough place, famous for the Brixton Riots in 1981, whereas Buxton, in Derbyshire, is a well-to-do and picturesque market town popular with tourists. In fact, Callum's misunderstanding goes deeper than this, as the Church Road he is talking about, famous for its gang violence and the grime artists Nines and Skrapz, is in fact in North London and not in Brixton at all. It is therefore plausible that Callum was especially aware at that point of how he was being perceived by others, and the self-correction was a fleeting example behind the scenes of this process.

CONCLUSION

I have tried to show how the use of th-stopping, a linguistic feature heavily associated with black varieties of English, is possibly being used in this particular context not as a marker of ethnicity, but as part of the process of enacting and performing an identity in relation to a particular way of life, a way of life that is embodied in the social practices of grime (especially) but also in hip hop and dancehall. These two example scenarios—the four boys in extract (1), and Callum in extracts (2) to (4)—show two ways in which [t] is being used in this way within an interaction. The two processes are similar in some ways, but different in others. The four boys are using [t] very much to take a stance that aligns them within the world created by the topic of conversation. Their precise involvement in that world is unclear, but at that moment, that is the reality they are creating. I am therefore suggesting that [t] is being used as a linguistic resource (alongside other linguistic and nonlinguistic resources), which helps to place them in that world in that moment. [t] carries this social meaning in this context by way of its indexical associations with rap, grime, and a general sense of ‘tough’ or ‘street’ culture. This link is reinforced by the quantitative analysis carried out previously which showed the meaningful correlations between an individual's engagement with this social practice and use of that particular variant. Callum also uses [t] as a resource in the performance of identity, with the variant again indexing some sense of street/tough/grime values. Yet the stance he is taking is in relation to that world rather than the particular interaction at that time. It seems to be a world that he is on the edges of, rather than embedded within, and his use of the variant is arguably more agentive and more conscious.

The extent to which the young people themselves feel that they align specifically with a grime lifestyle is debatable, especially the boys in extract (1). This is simply my reading of the situation based on the recorded and observed data, and it must always, like any such sociolinguistic analysis, remain partial. Callum, by contrast, does appear to be making an open and concerted effort to align himself with the lifestyle, perhaps because he is at present just that bit further away from it. However, almost regardless of how any of them view their own relation to grime as a music genre itself (or dancehall or hip hop), the ‘tough’, ‘street’ indexical resource of [t] is available to them to be used in this way as a result of their involvement. By invoking the practice of grime, I am putting it forward as a possibly useful and productive lens through which to view, analyse, and understand urban British youth language and identity. I am not suggesting that the use of [t] as a phonetic variant (or as a possible lexical variant in the case of, for example, ting and tief) has emerged in the speech of these young people purely as a result of their engagement with grime; clearly such forms have been around in British English for a long time (see e.g. Hewitt Reference Hewitt1986). Neither am I suggesting that by foregrounding this indexical link we should close our eyes to a likely relationship between the use of [t] and ethnicity after all. I am simply offering an interpretation of the sociolinguistic realities of a particular group of people, in a particular context, at a particular point in time. And within those constraints, th-stopping very much appears to be a grime ting.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

- <[ ]>

phonetic transcription

- [ ]

overlapping speech

- (.)

pause of less than one second

- (sec)

pause times in seconds

- ((laughter))

contextual or paralinguistic information

- (unclear)

unintelligible speech

- :

lengthening

- underline

emphatic stress