“Everything that I command you, you shall be careful to do. You shall not add to it or take from it.”

(Deuteronomy 12:32, ESV)“Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and obey it.”

(Luke 11:27–28, NIV)1 Introduction

Increasing evidence suggests that there are fundamental differences in the moral decisions of religious and non-religious individuals (Goodwin & Darley, Reference Goodwin and Darley2008; Graham & Haidt, Reference Graham and Haidt2010; Piazza, Reference Piazza, Landy and Goodwin2012; Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press; Tetlock, Reference Tetlock2003). It is well established that religious affiliation in America is a strong determinant of the content of people’s moral values and attitudes, for example, whether or not one opposes same-sex marriage, premarital sex, stem-cell research, or abortion (Layman & Carmines, Reference Layman and Carmines1997; Olson & Green, Reference Olson and Green2006; Pew Research Center, 2013; Putnam & Campbell, Reference Putnam and Campbell2010). However, recent findings suggest that it is not only the content of people’s moral attitudes that distinguishes religious and non-religious individuals, but also the form or nature of their moral thinking (Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press). In particular, recent studies suggest that religious individuals tend to adopt a deontological (rule-based) approach to morality more so than non-religious individuals (Piazza, Reference Piazza, Landy and Goodwin2012; Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press; see also Tetlock, Reference Tetlock2003).

According to utilitarian ethics, the rightness or wrongness of an action is derived from its total consequences, or the net good or bad effects it produces (Baron, Reference Baron2006; Brandt, Reference Brandt1992, Reference Brandt1998; Mill, Reference Mill1861/1998; Rosen, Reference Rosen2003; Singer, Reference Singer1993; Sinnott-Armstrong, Reference Sinnott-Armstrong2009a). Within this framework, actions that are likely to maximize good effects, or minimize the occurrence of bad effects, are those kinds of actions one is permitted, or obligated, to perform (though in this framework “good” and “bad” do not necessarily have to be defined strictly in terms of “welfare” and “suffering”; see Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press; Sinnott-Armstrong, Reference Sinnott-Armstrong2009a). By contrast, according to deontological ethics, the rightness or wrongness of an action depends on whether or not the action follows or violates a universalizable rule or duty that everyone is obligated to follow (Alexander & Moore, Reference Alexander and Moore2008; Baron & Spranca, Reference Baron and Spranca1997; Kant, Reference Kant1785/1964; Kohlberg, Reference Kohlberg1969). Within this framework, actions that are consistent with a rule or duty (e.g., to tell the truth or not to lie) are the kinds of actions one is obligated to perform, and actions that violate rules or duties are the kinds of actions one is forbidden to perform. While some forms of deontology allow for rules to be overridden when the benefits of doing so clearly outweigh the disutility (e.g., see Gert, Reference Gert2004), strict forms of deontology argue for an absolutist or non-negotiable commitment to rules, or “protected” (Baron & Spranca, Reference Baron and Spranca1997) or “sacred” values (Tetlock, Reference Tetlock2003), even in the face of beneficial outcomes or utilitarian incentives (e.g., Finnis, Reference Finnis1973).

A number of studies have uncovered a robust relationship between self-reported religiosity (measured in terms of belief, identity and practices) and the deployment of a deontological ethic. For example, studies by Piazza, (Reference Piazza, Landy and Goodwin2012) found that religious individuals are more likely than non-religious individuals to appeal to the governing force of a moral rule (e.g., “It is wrong to break a contract”), rather than appeal to the perceived harmfulness or negative social effects of an action, when justifying its wrongness. Piazza & Sousa, (Reference Piazza and Sousain press) established the relationship between religiosity and non-consequentialist thinking more extensively. They showed that religious individuals are reluctant to judge a range of transgressive acts (e.g., lying, stealing, defying authorities, etc.) as permissible even when these acts (a) produce more good than bad consequences, (b) prevent even greater wrongdoing of a similar kind, or (c) cause no harm at all. In a similar vein, Tetlock (Reference Tetlock2003) found that religious fundamentalists often reject the notion that taboo trade-offs—where a sacred value (e.g., the sanctity of human life) is set in conflict with a secular good (e.g., monetary gain)—should even be contemplated, let alone undertaken (see also Ginges, Atran, Medin, & Shikaki, Reference Ginges, Atran, Medin and Shakaki2007). In sum, the relationship between religiosity and a deontological ethic has been firmly established, but the question remains: what exactly underlies this association?

1.1 Past investigations of potential mediators

Past studies have looked at a number of potential variables that might help explain the association between religiosity and rule-based morality, but none of these variables seem to provide a satisfactory account. Piazza, (Reference Piazza, Landy and Goodwin2012) surmised that a dogged commitment to rules might be symptomatic of a fundamentalist, right-wing authoritarian, or conservative personality type—a character profile which has been linked to closed-mindedness, a greater need for structure, lower levels of cognitive complexity and need for cognition, greater pessimism about the human condition, belief in a dangerous world, and a desire to maintain the status quo (see Altemeyer, Reference Altemeyer1998; Duckitt, Reference Duckitt2001; Eidelman, Crandall, Goodman, & Blanchar, Reference Eidelman, Crandall, Goodman and Blanchar2012; Hinze, Doster, & Joe, Reference Hinze, Doster and Joe1997; Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloway, Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003). However, in Piazza’s studies, predictors of religiosity still predicted rule-based morality even after accounting statistically for authoritarianism-conservatism, religious fundamentalism, personal need for structure, and need for cognition, suggesting that other elements, beyond those related to fundamentalism and right-wing authoritarianism, underlie the relationship.

Piazza & Sousa, (Reference Piazza and Sousain press) tested whether an intuitive-thinking style might explain the deontological mindset of religious individuals. Research by Shenhav, Rand, and Greene (Reference Shenhav, Rand and Greene2011) has linked belief in God to an intuitive thinking style (i.e., trusting one’s immediate judgment on an issue, rather than reflecting or deliberating about alternative possibilities), as measured via the Cognitive Reflection Test (Federick, Reference Federick2005). Other research has linked a reflective-thinking style (the opposite of intuitive thinking) to the adoption of utilitarian principles in moral judgment (Baron, Reference Baron2013; Paxton, Ungar, & Greene, Reference Paxton, Ungar and Greene2012, but see Royzman, Landy, & Leeman, Reference Royzman, Landy and Leemanin press, for a more nuanced result). Tying together these two lines of research, Piazza & Sousa, (Reference Piazza and Sousain press) tested whether possessing a more intuitive than reflective thinking style might mediate the non-utilitarian moral judgments of religious individuals—for example, whether they would judge “harmless” taboo violations as permissible or impermissible (see Haidt, Bjorklund, & Murphy, Reference Haidt, Bjorklund and Murphy2000). Their results did not support this mediation hypothesis.

Theorizing by Graham and Haidt (Reference Graham and Haidt2010) suggests that there may be important differences in the content of religious and non-religious individuals’ “moral foundations,” or the moral values that they tend to emphasize, and that these differential values may explain some important differences in moral judgment. In particular, they proposed that, unlike their non-religious counterparts, religious individuals cherish virtues related to group loyalty, respect for authority, and bodily/spiritual purity—virtues that they argue promote group cohesion, more so than virtues such as concern for welfare and justice, which tend to be valued fairly equally by all people (see Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009). While Piazza & Sousa (Reference Piazza and Sousain press; Study 2) experimentally controlled for differences in the valuing of welfare as an explanation for the relationship religiosity has with deontological thinking, no studies to date have looked at whether moralizing content outside the scope of welfare or justice (e.g., respect for authority) might explain the relationship.

In the present paper, we posit that the deontological orientation displayed by religious individuals is not the result of individual differences in what domains of morality one emphasizes. Neither will we argue that the deontological ethic of religious individuals is shaped mainly by dispositional forces orthogonal to their religious commitments or beliefs, such as how reflective or actively open-minded they are. Rather, we propose that the deontological thinking of religious individuals is largely driven by their unique meta-ethical beliefs. More specifically, we hypothesize that religious individuals who endorse a belief that morality is founded on God’s moral authority, as opposed to originating from human reason or intuition, are those individuals who generally eschew the consideration of outcomes when judging the morality of an act, focusing instead on the consistency of the act with divinely-grounded moral principles.

1.2 Meta-ethics, Divine Command Theory, and utilitarian moral thinking

Meta-ethics refers to a set of beliefs that people have about the nature or properties of morality, including beliefs about the origin or foundations of morality—or where morality comes from (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1990; Smith, Reference Smith1994). Past research on the meta-ethical beliefs of lay individuals suggests that people vary in the extent to which they perceive various moral propositions (e.g., “It is wrong to steal”) as having an objective versus subjective foundation, that is, as having a truth-value that is either dependent or independent of human minds (see Goodwin & Darley, Reference Goodwin and Darley2008, Nichols, Reference Nichols2004; though people tend to perceive certain classes of moral propositions as more objective than other classes; see Goodwin & Darley, Reference Goodwin and Darley2012). To believe that morality is objective is to consider moral propositions (e.g., unjustly causing harm is morally wrong) to be more like mathematical facts (e.g., 2 + 2 = 4) than personal opinions (e.g., sneakers are more comfortable than sandals) or social conventions (e.g., do not wear pajamas to work), in that their truth value exists independent from what any person or group of persons thinks, wills, agrees to, or commands—but rather is rooted in some objective feature of the act (e.g., the needless causation of suffering; see also Nucci & Turiel, Reference Nucci and Turiel1993; Turiel, Reference Turiel1983).

For many religious individuals moral propositions obtain their moral objectivity by virtue of their origin in divine commands. Indeed, past research has found that belief in God is a reliable predictor of moral objectivity (see Goodwin & Darley, Reference Goodwin and Darley2008, Study 3). Within philosophy, the belief that moral propositions derive their truth value from their alignment with divine commands is known as Divine Command Theory (henceforth DCT; Nielsen, Reference Nielsen1990; Reference Sinnott-ArmstrongSinnott-Armstrong, 2009b). Although there are several different versions of DCT, one popular version argues that, insofar as we can trust God’s wisdom to be perfect and supreme, and God’s character to be perfectly righteous and just, if God wills or commands us to do or not to do something, it is our moral duty to do or not to do it.Footnote 1 On this account, if God commands that murder is wrong (e.g., Qur’an 17:31, 33), then it is wrong to commit murder and it is our moral duty to not commit murder. Furthermore, because the truth-value of the moral claim that killing is wrong is dependent upon the perfect wisdom and goodness of God (“God knows what is best”), and the fact that God issued a command forbidding killing, and not upon the positive or negative effects it produces, DCT implies that it is our moral duty not to violate this divine command, even if doing so would produce better outcomes overall (e.g., taking a life to assuage a person’s suffering from a terminal illness).

This feature of DCT—that divinely ordained moral rules are to be respected and not violated, even in the face of what appear to be positive outcomes—accords with aspects of a strict or absolutist deontological ethic,Footnote 2 which asserts that certain moral acts (e.g., murder, lying) are absolutely wrong and strictly forbidden, and therefore should not be performed. These common features between DCT and absolutist deontological ethics may account for the resistance religious individuals have towards utilitarian thinking insofar as religious individuals are likely to endorse a DCT view of morality. Indeed, this seems to be the case. For many contemporary religious individuals, particularly those within the Abrahamic monotheistic (Jewish-Christian-Muslim) traditions, God is the ultimate source of moral truth (i.e., God has perfect moral wisdom), and it is only through divine revelation (recorded and transmitted through holy texts or scripture) that people come to know this truth (Gunton, Reference Gunton2005; Putnam & Campbell, Reference Putnam and Campbell2010; Wade, Reference Wade2009). Furthermore, for many religious people, divine authority is not to be questioned, either out of respect for God’s supreme wisdom or for fear of inciting His wrath (e.g., Genesis 22:5-8; Isaiah 55:8-9; Job 34:12; Qur’an 6:151; Romans 1:18; see also Aquinas, ca. Reference Aquinas1273/1947; Boyer, Reference Boyer2001; Johnson & Bering, Reference Johnson and Bering2006; Shariff & Rhemtulla, Reference Shariff and Rhemtulla2012).

Related to a belief in divine moral authority is a belief in the inadequacy of human nature as a source of moral knowledge or action (Sinnott-Armstrong, Reference Sinnott-Armstrong2009b). Within the Judeo-Christian religion this is referred to as the doctrine of “original sin” (e.g., Ephesians 2:8-9; Psalm 51:5; see also Aquinas, ca. Reference Aquinas1273/1947; Bonaiuti & La Piana, Reference Bonaiuti and La Piana1917). According to the doctrine of original sin, human nature was corrupted by an initial act of disobedience to God by Adam and Eve (humankind’s first parents; see Genesis 3). As a result, all of humanity is ethically debilitated, such that without God’s guidance a person remains ignorant of what is right and wrong, and will naturally choose evil (e.g., Romans 5:12-21). The doctrine of original sin thus postulates a pessimistic view of human nature, and, by extension, a pessimistic view of human judgment. Thus, for many religious individuals, the path to good moral judgment is following God’s perfect moral authority (e.g., Psalm 119:66), rather than relying on one’s own imperfect thinking about how to behave (see esp. Isaiah 55:8-9; Proverbs 3:5).

If religious individuals are more likely than non-religious individuals to endorse DCT, this belief may explain their unwillingness to violate moral rules in the pursuit of a greater good. To illustrate, consider the example of homosexuality and same-sex marriage. Since homosexual conduct is not harmful when practiced among consenting adults—indeed, it is often the expression of deep love and affection—then from a utilitarian perspective it should not be deemed wrong, despite the existence of any divine command forbidding it. From a DCT perspective, however, if there exists a divine command forbidding homosexual acts, as in the Judeo-Christian tradition (see Leviticus 18:22, 20:13; Romans 1:26-27), then the absence of harm does not nullify the act’s wrongness. Thus, an understanding of DCT endorsement goes a long way in explaining the “gap” that exists between religious and non-religious with respect to homosexuality and same-sex marriage. Individuals who reject DCT on epistemic grounds are free to endorse same-sex marriage for utilitarian reasons. In this research, we test whether differences in meta-ethical beliefs also explain the gap between religious and non-religious individuals in their endorsement of utilitarian morality more generally.

1.3 Overview of studies

Here we examined the role of DCT endorsement as an explanation for the negative link between religiosity and utilitarian thinking within American samples. Since, to our knowledge, no psychometric instrument is designed to assess belief in DCT, our first aim in Study 1 was to devise a reliable instrument that would do this. As our second aim, we sought to show that our new instrument would mediate the negative relationship that other indices of religiosity have with utilitarian thinking, to establish DCT as the active ingredient underlying the relationship observed in past studies. Additionally, as an ancillary goal in Study 1, we tested whether DCT endorsement would largely explain the well-established relationship between religiosity and social conservatism (Lewis & Maltby, Reference Lewis and Maltby2000; Putnam & Campbell, Reference Putnam and Campbell2010; Rowatt, LaBouff, Honson, Froese, & Tsang, Reference Rowatt, LaBouff, Johnson, Froese and Tsang2009). Many social conservative values—for example, taking a strong opposing stance towards abortion, divorce, or premarital sex—may be buoyed by the perception of divine commands (codified in holy texts or scripture) supporting a particular way of life or forbidding specific social acts. Thus, it is plausible that DCT is the primary factor sustaining the link between religiosity and social conservatism as well. Finally, in Study 1 we sought to show that our new instrument predicts these moral-decision outcomes independent of actively open-minded thinking (AOT), a trait-level cognitive variable involving an openness towards revising one’s beliefs or judgments in light of new or opposing evidence (see Haran, Ritov, & Mellers, Reference Haran, Ritov and Mellers2013), that has been negatively linked to religiosity (Baron, Scott, Fincher, & Metz, Reference Baron, Scott, Fincher and Metz2013, Study 4). As some have argued, a commitment to rules may be buttressed by an unwillingness to revise one’s moral position on an issue despite the utility stemming from the act (see Baron, Reference Baron2011, 2013; Paxton & Greene, Reference Paxton and Greene2010), thus, we included a measure of AOT in Study 1. We also included measures of Big Five personality to test the discriminant validity of our new scale.

Past research has shown that utilitarian thinking may be measured in terms of a stable cognitive style or orientation, plotted along a continuum (Lombrozo, Reference Lombrozo2009; Piazza, Russell, & Sousa, Reference Piazza, Russell and Sousa2013; Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press; but see Tanner, Medin, & Iliev, Reference Tanner, Medin and Iliev2007, for a different view). On one end of the continuum are strong deontological thinkers, who tend to believe that most rules (e.g., telling the truth) cannot be violated for any reason. On the other end of the continuum are strong utilitarian thinkers, who perceive that most rules or duties should be violated when doing so produces more good than bad consequences (e.g., stealing food or medicine to save a life). “Strong utilitarian thinkers” may be further differentiated from “weak utilitarian thinkers” in that strong utilitarians believe that it is a moral duty to violate rules when following the rule would prevent a greater good, while weak utilitarian thinkers view such rule violations are merely permissible, though not mandatory (see Lombrozo, Reference Lombrozo2009; Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press; Rozyman et al., in press). Consistent with previous research, in Study 1 we assessed utilitarian thinking styles using Piazza and Sousa’s (in press) Consequentialist Thinking Style scale, which assesses subjects’ moral position across thirteen different rule violations (e.g., deception, spreading gossip). For each transgression, participants may rule the act to be: (a) impermissible (deontological response), (b) permissible when there are more good than bad consequences (weak utilitarian response), or (c) obligatory when there are more good than bad consequences (strong utilitarian response). Consistent with previous findings (Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press), we hypothesized that our measures of religiosity would be negatively associated with a utilitarian thinking style. However, extending past findings, we predicted that our novel measure of DCT endorsement would mediate the relationship that these measures have with utilitarian thinking.

In Study 2, we sought to extend our investigation beyond utilitarian thinking measured at the level of abstract principles, to establish DCT as a mediator of the role religiosity plays in contextualized moral judgments. To this end, we presented a new sample of American participants a series of naturalistic moral dilemmas in which utilitarian principles and deontological principles were placed in conflict. The dilemmas covered a range of normative content, from telling the truth to obeying authority. For each dilemma, participants rated on a bipolar scale whether they would favor abiding by the relevant deontological rule or violating the rule to produce a greater good. Consistent with our hypothesis from Study 1, our prediction was that an endorsement of DCT would mediate the negative relationship between religiosity and preferring a utilitarian resolution to the dilemma. Additionally, in Study 2, we addressed some alternative explanations for our results, including differences in moral foundations (Haidt, Reference Haidt2012; Haidt & Graham, Reference Haidt and Graham2007) and beliefs about the function of moral rules.

2 Study 1

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

We recruited a sample of 290 adults (136 male, 154 female; M age=34.02 years, SD=11.40) via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk in exchange monetary compensation. Only individuals located in the United States were allowed to participate. The religiosity of the sample was 20% Protestant, 12% Catholic, 7% Evangelical, 10% Other Christian, 6% Non-Christian religion (e.g., Jewish, Hindu), 5% Personal spirituality, 15% Agnostic, 22% Atheist, and 3% None or no religion/faith. The sample was also politically diverse: 43% Democrat, 19% Republican, 32% Independent, and 6% other or not political.

2.1.2 Scale development

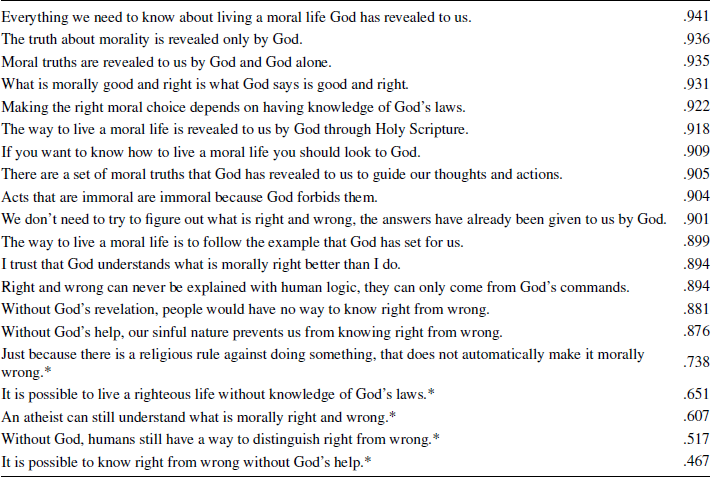

Twenty statements about God’s role (or, conversely, humankind’s role) in establishing or determining moral truths were generated by the authors via rational-empirical methods. Level of agreement with the items was assessed on 1 (Strongly disagree) to 9 (Strongly agree) scales, and responses were submitted to exploratory factor analysis and tests of convergent and discriminant validity. The twenty-item Morality Founded on Divine Authority scale (MFDA), along with loadings for each item on the first principal component, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: First principal component loadings of the 20-item Morality Founded on Divine Authority (MFDA) scale.

* Reverse-scored.

2.1.3 Measures of religiosity

Religiosity was assessed using several different pre-existing metrics (see appendices for all scales and items). Since the sample was American, and Christianity is the dominant religion in the U.S., we included Hunsberger’s (1992) Short Christian Orthodoxy (SCO) scale (Cronbach’s α = .96), which contains six items assessing endorsement of orthodox Christian doctrine. In previous research, this scale was found to correlate strongly with a preference for rule-based, as opposed to outcome-based, moral arguments (Piazza, Reference Piazza, Landy and Goodwin2012). We used the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire (SRFQ; Plante & Boccaccini, Reference Plante and Boccaccini1997; α = .98), which includes ten items that assess, in a more general and faith-neutral way, the importance of religious practices and faith within a person’s life. This scale has been shown to predict a deontological thinking style in past research (Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press; Study 2). We also included the 12-item Attitude towards Religion (ATR) scale (Piazza, Landy, & Goodwin, Reference Piazza, Landy and Goodwin2012; α = .94), which assesses positive attitudes towards religion and its role in society. All religiosity measures were assessed in terms of agreement on 1–9 scales. Additionally, as a more direct measure of religiosity, participants rated on a 1–9 scale how religious they are (1 = Not at all religious; 9 = Extremely religious).

2.1.4 Utilitarian thinking and social conservatism

Utilitarian thinking was assessed via Piazza et al.’s (Reference Piazza, Russell and Sousa2013) Consequentialist Thinking Style scale (CTS; see also Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press), which has participants respond to 13 questions in which they indicated whether a counternormative act was never morally permissible (deontological response), permissible if it produces more good than bad (weak utilitarian response) or obligatory if it produces more good than bad (strong utilitarian response). The 13 acts were lying, killing, assisted suicide or voluntary euthanasia, torture, stealing, incest, cannibalism, betrayal, deception, gossip, breaking promises, breaking the law, and treason. We also added a fourteenth item, abortion, not included in the original thirteen-item scale.Footnote 3 The 14 items had good internal reliability (α = .85; see Appendix A for the 14-item scale). We averaged participants’ responses to the 14 items, ranging from 1 to 3, such that higher scores represent a stronger commitment to utilitarian thinking.

Social conservative values were assessed using a revised version of Henningham’s (Reference Henningham1996) Scale of Social Conservatism. Henningham’s original 12-item scale was designed for an Australian audience over a decade ago. Some of the items are not relevant for an American audience (e.g., Asian immigration) or are no longer controversial (e.g., multiculturalism). Thus, we revised the scale with an American audience in mind, using some items appearing in Putnam and Campbell’s (Reference Putnam and Campbell2010) Faith Matters Survey, conducted with a U.S. sample. This internally reliable (α = .77), 13-item scale appears in Appendix A. Participants indicated their position dichotomously on each social issue by selecting “Opposed to it” or “NOT opposed to it”.

2.1.5 Actively open-minded thinking

We measured actively open-minded thinking with seven items from Haran et al.’s (Reference Haran, Ritov and Mellers2013) Actively Open-minded Thinking scale (AOT, α = .79; Appendix A), which participants rated in terms of level of agreement on a 1–9 scale. This scale measures a tendency to be open towards revising and updating one’s beliefs in light of new or contradictory evidence. As a measure of Big Five personality, we included John and Srivastava’s (Reference John and Srivastava1999) 44-item Big Five Inventory, which provides indices of Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness to experience. The Big Five were included to test for discrimination with the MFDA as a predictor of utilitarian thinking. Participants rated on a 1–9 scale how strongly various behavioral tendencies (e.g., “Likes to reflect, play with ideas”) represents who they are as a person (for complete list of items, see John & Srivastava, Reference John and Srivastava1999).

2.1.6 Procedure

Participants answered the CTS and social conservatism items first, followed by the religiosity measures, MFDA, AOT, Big Five measures, and demographics. No other measures were included. All participants were debriefed and paid at the end.

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Scale reliability

The twenty items of our new MFDA scale had a very high internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = .98). We conducted a principal components analysis, without rotation, of the twenty items, with parallel analysis (O’Connor, Reference O’Connor2000) as our extraction method. Only the first eigenvalue (14.24, explaining 71.20% of the total variance) exceeded those derived by chance via parallel analysis. Thus, only one factor was retained. This factor was comprised of all twenty items (Table 1); all twenty items loaded well above the conventional .40 cut-off (Kline, Reference Kline1994), with the reverse-scored items exhibiting the weakest loadings.

2.2.2 Convergent and discriminant validity

Table 2 presents zero-order correlations between the MFDA scale, religiosity, AOT, and outcome variables. As can be seen, believing that morality rests on God’s authority was found to highly correlate with our other metrics of religiosity, suggesting good convergent validity. Moreover, dimensions of the Big Five were only weakly correlated with MFDA (rs ranged from −.14 [Openness] to .16 [Agreeableness], ps < .05 except Conscientiousness: r = .10, p > .10), suggesting good discriminant validity. As predicted, MFDA negatively correlated with utilitarian thinking and AOT, and positively with social conservatism.

Table 2: Correlation matrix of religiosity, AOT, and outcome variables from Study 1 (Pearson’s r used for all columns except Social Conservatism, which used Spearman’s ρ). MFDA = Morality Founded on Divine Authority scale; SCO = Short Christian Orthodoxy scale; SRFQ = Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire; ATR = Attitude towards Religion scale. AOT = Actively Open-minded Thinking scale. CTS = Consequentialist Thinking Style scale. All presented correlations are statistically significant, ps < .001.

2.2.3 Correlations between self-reported religiosity and utilitarian thinking

Replicating previous findings (Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press), self-reported religiosity (measured with a single item) correlated negatively with utilitarian thinking for thirteen out of fourteen moral transgressions (rs = −.13 [breaking promises] to −.50 [abortion], ps < .03), the exception being torture, which was unrelated to religiosity (r = −.04, p = .47), as it was in Piazza and Sousa’s prior research. Correlations between self-reported religiosity and utilitarian thinking were very similar when “weak” and “strong” utilitarian responses were collapsed (= 1) and scored separately from deontological responses (= 0), Spearman’s ρs ranged from −.15, p < .01 (breaking promises) to −.52, p < .001 (abortion), with the exception of torture, ρ = −.06, p = .31. All subsequent analyses used the conventional three-point CTS score.

2.2.4 Mediation analysis of religiosity metrics and utilitarian thinking

The main purpose of this research was to demonstrate that endorsement of DCT accounts for the link between religiosity and non-utilitarian morality. To formally test the role of MFDA in mediating this relationship, we used a series of bootstrapping procedures (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2004) to estimate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the indirect effect of each religiosity measure via MFDA on utilitarian thinking, using 5,000 bootstrap resamples. We conducted analyses for all four of our religiosity measures, with the religiosity measure as the independent variable, MFDA as the mediator, and CTS as the dependent variable. The 95% CIs for the indirect effect of religiosity through MFDA did not contain zero in all four analyses (SFRQ [−.056, −.015]; SCO [−.048, −.010]; ATR [−.073, −.023]; self-reported religiosity [−.070, −.020]), and the direct effects of religiosity was not significant in any analysis, all ps > .07 (ps > .09 using 13-item CTS).

Importantly, to test the reverse causal direction (degree of religiosity as a mediator of MFDA and utilitarianism) we conducted similar bootstrapping procedures with our religiosity measures entered as mediators of the relationship between MFDA and CTS. In all four analyses, religiosity was not a mediator of MFDA and utilitarian thinking: the direct effect of MFDA remained significant all ps < .001 when religiosity was treated as a mediator, and the indirect effect of MFDA through religiosity was not significant (95% CIs SRFQ [−.035, .016]; SCO [−.042, .002]; ATR [−.031, .005]; self-reported religiosity [−.037, .007]).

The preceding findings suggest that endorsement of DCT accounts for the relationship between religiosity and non-utilitarian thinking within a religiously diverse American sample. However, since one of our measures of religiosity (SCO) was relevant only to religious individuals with a Christian faith, it would be important to determine whether endorsement of DCT also explains differences in moral orientation within our sub-set of Christian participants (n = 139) for this measure. Thus, we conducted a separate bootstrapping procedure for the SCO, this time excluding non-Christian participants from the sample. MFDA still emerged as a significant mediator of the relationship Christian Orthodoxy had with utilitarian thinking style (e.g., the indirect effect of Christian Orthodoxy through MFDA 95% CIs [−.066, −.021]; direct effect, p = .21). Thus, the relationship was robust with and without non-Christians in the sample.

2.2.5 Mediation analysis of religiosity and social conservatism

Similar bootstrapping procedures were run for the religiosity measures and social conservatism, treating MDFA as the mediating variable. The indirect effect of religiosity through MFDA on social conservatism was significant for all four religiosity measures (95% CIs SRFQ [.030, .053]; SCO [.033, .058]; ATR [.047, .074], self-reported religiosity [.039, .070]; direct effects, all ps > .092).

2.2.6 MFDA predicts utilitarian thinking independent of AOT and the Big Five

When MFDA was entered into a regression as a predictor of utilitarian thinking simultaneously with the Big Five and AOT, it remained a significant independent predictor, β = −.31,Footnote 4 t(282) = −4.37, p < .001, along with AOT, β = .17, t(282) = 2.43, p < .02, Agreeableness, β = −.25, t(282) = −4.43, p < .001, and Conscientiousness, β = −.15, t(282) = −2.58, p = .01 (all other β s < .07, ps > .24). In a similar analysis for social conservatism, MFDA remained a significant independent predictor, β = .59 (compared to .68 without additional covariates), t(282) = 10.08, p < .001, along with AOT, β = −.16, t(282) = −2.70, p < .01, and Conscientiousness, β = .13, t(282) = 2.55, p = .01 (all other β s < .08, ps > .14). Thus, endorsement of divine command theory was an important predictor of utilitarian thinking independent of other relevant personality dimensions, such as how actively open-minded, conscientious, or agreeable a person is.

2.3 Discussion

The results of Study 1 largely confirmed our hypothesis that differences in meta-ethics account in large part for the relationship between religiosity and moral thinking styles. Furthermore, the results confirmed the validity of our measure of DCT endorsement: MFDA showed high internal reliability, as well as clear convergent and discriminant validity. Regarding convergent validity, the MFDA correlated positively with other existing measures of religiosity, each emphasizing a slightly different aspect of religiosity (e.g., beliefs vs. practices). Regarding discriminant validity, the MFDA was only weakly correlated with theoretically unrelated personality constructs, such as the Big Five dimensions. Furthermore, the MFDA fully mediated the relationship each religiosity measure had with a utilitarian thinking style, as well as social conservatism. The MFDA also retained a strong relationship with both utilitarian thinking and social conservatism independent from measures of AOT and the Big Five.

3 Study 2

Despite these promising results, Study 1 had some limitations that we sought to overcome in Study 2. First, Study 1 did not rule out a plausible alternative explanation for our findings—namely, that endorsement of divine command theory might derive from a more general concern for authority, broadly defined. According to Moral Foundations Theory (MFT; Haidt & Graham, Reference Haidt and Graham2007), respect for authority is a virtue emphasized in many cultures and was shaped by our evolutionary history as primates living in hierarchically-structured groups of dominant and submissive members. It is known that political conservatives in America are more concerned with this moral foundation than liberals (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009). Thus, it could be that belief in DCT is part of a more general concern for respecting legitimate authorities—including, but not limited to, God’s authority. Study 2 sought to address this possibility, by including in our analysis the Authority subscale of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (or MFQ; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009).

Another untested variable that might explain our findings has to do with differences in the perceived function of rules. As discussed earlier, a fundamental tenet of Judeo-Christian faith is that humans are naturally sinful, and their wisdom is inferior to the supreme wisdom of God. Pessimism about the human condition might promote a deontological ethic: if humans are incapable of making good moral decisions on their own—for example, if we cannot figure out, in a given situation, what the right course of action is—then moral rules (revealed by God and grounded in His infallible wisdom) become necessary to guide us towards making ethical decisions. Thus, a belief in original sin, or the inherent corruptness of human nature and the fallibility of human judgment, might explain why religious individuals exhibit a strong commitment to deontological ethics—it is because they tend to see moral rules as functioning to prevent people from naturally making the wrong decision by trusting their own corrupt and imperfect judgment over God’s perfect judgment.

We tested this possibility in Study 2 using a new measure that we designed to discriminate between four possible functions people may perceive moral rules to fulfill: (1) rules protect people from one another (welfare function); (2) rules prevent one person from having an unfair advantage over another (fairness function); (3) rules guide people to make better moral judgments than they would on their own (guidance function—humans are fallible); (4) rules guide people to act better than they would on their own (guidance function—humans are naturally sinful). The first two functions are consistent with the harm principle of criminal law (i.e., that all persons are entitled to protection from harm from other persons; Feinberg, Reference Feinberg1984), and basic contractualist notions of justice (e.g., the Rawlsian notion that the moral principles people agree to should apply to all persons equally, regardless of race, sex, station, etc.; Rawls, Reference Rawls1971), while the latter two relate to our discussion of original sin and pessimism about human judgment. We made no predictions about whether the welfare and fairness functions would discriminate between religious and non-religious individuals, but we nevertheless included them for completeness. Instead, our main interest was the “guidance” functions. We predicted that religiosity would correlate with a perception that rules exist to counteract human fallibility and natural sinfulness, but we did not expect this variable to account for the relationship between religiosity and utilitarianism over and above the mediating role of DCT endorsement.

Furthermore, in Study 1, utilitarian decision-making was measured in relation to abstract situations, rather than contextualized events. If endorsement of DCT is truly what underlies the relationship religiosity has with deontological thinking, then we should be able to replicate our results at the level of specific moral dilemmas. To this end, in Study 2 we assessed utilitarian thinking via participants’ judgments of a variety of moral dilemmas which placed deontological principles in conflict with utilitarian ones, in order to show that our results generalize from global endorsement of moral principles to resolution of specific dilemmatic moral judgments.

Lastly, in addition to these primary objectives, Study 2 also investigated one ancillary issue pertaining to the relationship between religiosity and Moral Foundations Theory (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Haidt & Graham, Reference Haidt and Graham2007). MFT is a theory about the content of people’s moral judgments. It argues that there are at least five (possibly six)Footnote 5 distinct foundations, or domains of moral condemnation, grounded in five intuitive “moral systems” in the brain. These foundations include: Harm/care, Fairness/cheating, Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/disrespect, and SanctityFootnote 6/degradation. According to MFT, each moral system was designed by natural selection to respond to a unique set of social input; for example, it is postulated that the Care foundation is activated by signs of pain and suffering, while the Authority foundation is activated by insubordination directed at respected leaders or authorities. MFT proposes that, although human societies differ in the degree to which they promote the cultivation of each foundation, all human beings possess the intuitive architecture supporting processes related to each (Haidt, Reference Haidt2012; Haidt & Graham, Reference Haidt and Graham2007).

Consistent with this idea, research on MFT has found that specific individuals within American society differ in terms of how strongly they utilize content from each foundation within their moral judgments. In particular, Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009) found that political conservatives in America tend to utilize content from all five foundations in their moral judgments, while American liberals utilize mostly content from the Care and Fairness foundations. According to Graham et al., the reason that liberals discount content related to Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity in their moral judgments has mostly to do with the “social function” of these three foundations. It is argued that the foundations of Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity function primarily to limit the advance of individualism and self-expression, and to “bind together” people into groups such as families, tribes, and nations. It is surmised that, because liberals value autonomy and have a reduced investment in group-based enterprises, relative to conservatives, their lack of group-oriented values are reflected in their moral judgments (i.e., in their lack of concern for violations of authority, loyalty, or sanctity). A similar argument has been offered to account for differences in religious and non-religious individuals (see Graham & Haidt, Reference Graham and Haidt2010; Haidt, Reference Haidt2012).

Though we do not challenge the legitimacy of this “social function” explanation for why American liberals and conservatives differ in their valuing of different moral content, we do question whether differences in group orientation are sufficient, or even necessary, to explain why religious individuals, but not non-religious individuals, might prioritize concerns beyond those of harm or fairness. We propose instead that one principal reason religious individuals have a more expansive set of foundations (or moral concerns) is due to their meta-ethical belief that morality is founded upon divine authority. Insofar as divine commands (codified in religious texts) generally cover a broader range of issues than those pertaining to welfare and fairness, including obedience to authority, loyalty to one’s ingroups, and, in particular, concern for sexual/bodily purity (see footnote for examples),Footnote 7 we expect endorsement of DCT to account for much of the relationship religiosity has with the “binding” moral foundations. Specifically, we predict that endorsement of DCT will mediate the relationship religiosity has with Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity—foundations theorized to distinguish between religious and non-religious individuals.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

We recruited a new sample of 211 adult participants (99 female; M age = 33.24 years, SD = 12.23) via the same web service in exchange for monetary compensation. Recruitment was limited to individuals located in the U.S. The sample was religiously diverse: 16% Protestant, 14% Catholic, 4% Evangelical, 12% other Christian faith, 4% Jewish, 2% Hindu, 2% Buddhist, 2% other religion/faith, 5% Personal Spirituality, 19% Atheist, 14% Agnostic, 6% no religion/faith. The sample was also politically diverse: 43% Democrat, 18% Republican, 37% Independent, 2% other or not political.

3.1.2 Procedures

Participants answered 11 moral dilemmas, three questionnaires, and demographic questions, including self-reported religiosity, political orientation, level of education, and socioeconomic status. Whether or not participants completed the dilemmas prior to the questionnaires was counterbalanced. All participants were debriefed and paid at the end.

3.1.3 Materials

Moral dilemmas.

We developed 11 moral dilemma scenarios in which a decision had to be made between adhering to a deontological rule (e.g., do not lie) or breaking that rule to produce a greater overall good outcome (see Appendix B for all eleven dilemmas). These scenarios therefore have the same basic structure as utilitarian dilemmas used extensively in other research (e.g., Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, Reference Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley and Cohen2001; Paxton et al., Reference Paxton, Ungar and Greene2012). However, whereas the dilemmas used in prior research focus exclusively on breaking the deontological prohibition on killing in order to save more lives (so-called “trolley-type” dilemmas, named for the famous trolley problem), our dilemmas presented situations in which a wide range of deontological rules, not just those pertaining to killing, could be broken to produce better consequences. Many of these rules overlapped with those assessed by the CTS in Study 1 (e.g., lying, infidelity, breaking promises, etc.). Our materials therefore offered a more complete assessment of whether a person’s moral judgments are generally deontological or utilitarian. They were also intended to be somewhat less stylized and more naturalistic than classic trolley-type dilemmas, which have been criticized for their severity and exoticness (e.g., see Bartels & Pizarro, Reference Bartels and Pizarro2011). Participants indicated what they felt they should do in each situation on a 1–9 scale ranging from “definitely should [action obeying the deontological rule]” to “definitely should [action breaking the deontological rule]” and anchored at the midpoint by “I’m completely divided about what to do.” Higher scores therefore indicated a greater endorsement of a utilitarian resolution to the dilemma.

Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ).

The 30-item Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ; see Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva, & Ditto, Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011, for materials), assesses commitment to the five broad “foundations” of morality postulated by MFT. The survey consists of two parts. The first part asks participants to rate the relevance of several factors when making moral judgments (e.g., “whether or not someone was cruel” for the Care foundation). The second part assesses agreement with a variety of statements that reflect or negate one of the five foundations (e.g., “I am proud of my country’s history” for Loyalty). The items were administered using the standard zero-to-five response scales (see Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009). Part 1 was presented before Part 2, and the order of question presentation within each part was randomized for each participant.

Perceived function of rules.

To assess participants’ pessimism about human nature and humankind’s ability to make responsible choices in the absence of moral rules, we developed twelve items assessing what participants considered to be the function of moral rules. Specifically, participants were instructed: “Think about the rules that people in society should strive to abide by—the rules one can be punished for failing to keep. Then answer the following statements in terms of your level of agreement or disagreement about why those rules are in place.” Participants then rated their agreement with twelve statements on a 9-point scale. Three items assessed pessimism about human morality because of the perceived sinful nature of humanity (e.g., “The rules exist to prevent people from acting on their natural, sinful impulses”). These items therefore assessed an “original sin” view of humanity. Three more items assessed a more general view that human judgment is unreliable or fallible, though not necessarily inherently evil (e.g., “The rules exist because people do not always know what the best course of action is”). The other six items were comprised of three items assessing harm-based and fairness-based justifications for the existence of rules (e.g., “The rules exist to stop people from hurting each other”; “The rules exist to create an equal playing field for all”). These latter six items were not related to pessimism about human moral judgment and were therefore of less immediate theoretical interest. The order of presentation of the twelve items was randomized for each participant; see Appendix C for all twelve items.

Morality is Founded on Divine Authority (MFDA).

The 20-item MFDA scale was administered as in Study 1 on a 9-point scale. The reliability of the scale was very strong (α = .97).

Religiosity and political orientation.

Self-reported religiosity was assessed with the same single-item measure from Study 1. Political orientation was measured via two items in which participants reported their political views on social issues and, separately, economic issues, on a 7-point bipolar scale (1 = Very liberal; 7 = Very conservative). The two items (α = .86) were aggregated into a single index with higher scores representing greater political conservatism. Level of education was measured on a scale from 1 (Some high school education) to 7 (Graduate degree, Doctorate). Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured via the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (see Adler, Epel, Castellazzo, & Ickovics, Reference Adler, Epel, Castellazzo and Ickovics2000). Measures of SES and education were included based on some research that has linked higher social class to lower religiosity (Paul, Reference Paul2010), decreased concern for the welfare of others (Stellar, Manzo, Kraus, & Keltner, Reference Stellar, Manzo, Kraus and Keltner2012), and an increased concern for rule compliance (Lammers & Stapel, Reference Lammers and Stapel2009).

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Factor analysis of Function of Rules items

Before using our new function of rules measure in our analysis, we first wanted to explore whether the four subscales were differentiated from each other in the manner that we intended. To test this, we submitted participants’ responses to the 12 items to Principal Components Analysis with Varimax rotation. Based on the results of a parallel analysis (O’Connor, Reference O’Connor2000), two factors were retained. The first factor (eigenvalue = 5.11) consisted of the Welfare and Fairness items, and the second (eigenvalue = 2.53) consisted of the Guidance items (fallible and sinful). Factor loadings were acceptably high (> .62), and cross-loadings were generally low (< .41). On the basis of this analysis, we combined the Welfare and Fairness items and the sinful and fallible Guidance items, giving us two final scales tapping participants’ beliefs about why rules exist, one related to traditional legal and philosophical justifications about preventing harm and ensuring fairness, and another related to beliefs that humans are at best flawed decision makers and at worst inherently evil, and therefore need rules to guide them. We used these two six-item scales in all subsequent analyses.

3.2.2 Preliminary analysis of religiosity, MFDA, political conservatism, and utilitarian decisions

Table 3 presents the correlations between self-reported religiosity, political conservatism, and utilitarian responding to each dilemma. It can be seen that religiosity correlated with utilitarian responding in the predicted direction in ten out of 11 dilemmas. We also averaged responses to the 11 moral dilemmas to create an index of utilitarian thinking (α = .68). Consistent with the findings of Study 1, there was an overall moderate, negative correlation between self-reported religiosity and average utilitarianism scores (Table 3). Moreover, we also observed a moderate negative correlation between political conservatism and utilitarianism (Table 3). This negative relationship was observed for all but two of the individual dilemmas. Therefore, the previous result that religious and conservative individuals tend to be less utilitarian in their moral thinking (Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press) replicates when utilitarianism is measured using specific moral dilemmas rather than measures of general endorsement of utilitarianism. In addition, the MFDA was negatively correlated with utilitarian responding for all eleven dilemmas (Table 3).

Table 3: Pearson correlations between religiosity and political conservatism, Morality Founded on Divine Authority (MFDA), and utilitarian decisions (Study 2). N = 211. * p < .05.

N = 211

* p < .05.

Zero-order correlations between the main variables of Study 2 are presented in Table 4. Noteworthy was a significant negative relationship between the guidance function of rules subscale and our index of utilitarian judgments. As predicted, perceiving rules as existing to counteract human fallibility and inherent sinfulness correlated with a tendency to make deontological judgments.

Table 4: Pearson correlations between the main variables from Study 2. MFDA = Morality is Founded on Divine Authority scale. N = 211. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

N = 211.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

To further probe the negative relationship between MFDA and utilitarian responding, we conducted a stepwise linear regression (Table 5). We first entered basic demographic variables including religiosity and political conservatism as predictors in step 1. Religiosity was the only significant (negative) predictor of utilitarian responding in this model. In step 2, we added MFDA. In this model, MFDA significantly negatively predicted utilitarian responding, but the predictive effect of self-reported religiosity did not remain significant when including MFDA in the model. In step 3, we added the responses to the function of rules items, and in step 4 we added the MFQ, but neither of these additions significantly improved model fit. The only significant predictor of utilitarian responding in the final model was MFDA (Table 5). The association between endorsement of divine command theory and deontological morality is therefore highly robust, and cannot be explained by differences in religious and non-religious individuals’ beliefs about the function of rules, level of education or SES, or endorsement of different moral foundations.

Table 5: Stepwise linear regression: Standardized regression coefficients predicting utilitarian decisions (Study 2). MFDA = Morality is Founded on Divine Authority scale. MFQ = Moral Foundations Questionnaire. N = 211. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

N = 211.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

3.2.3 Mediation analysis

We next sought to demonstrate again that the MFDA mediates the zero-order association between self-reported religiosity and deontological responding. As in Study 1, we conducted a bootstrapping analysis with 5,000 resamples. The indirect effect of religiosity on utilitarian decisions through MFDA was significant (95% CI [−.241, −.065]). Moreover, the direct effect of religiosity on utilitarian responding was not significant when controlling for MFDA (p = .07), as in the above regression analysis. Also, in a reverse mediation analysis, where religiosity was treated as the mediator of MFDA and utilitarian decisions, the indirect effect through religiosity was not significant (95% CIs [−.168, .001]). In short, endorsement of DCT fully mediated the relationship between religiosity and utilitarian moral judgment—i.e., DCT is the part of being religious that seems to account for the deontological leanings of religious individuals.

We sought to test a secondary hypothesis that endorsement of divine command theory also mediates the relationship religiosity has with the “binding” moral foundations. Thus, we conducted a series of bootstrapping procedures, in which MFDA scores were entered as the mediator of religiosity and each of the binding foundation subscales (Sanctity, Loyalty, and Authority). We used 5,000 resamples for each analysis. As can be seen in Figure 1, MFDA significantly mediated the relationship between religiosity and sanctity (95% CIs [.28, .44]), religiosity and loyalty (95% CIs [.05, .20]), and religiosity and authority (95% CIs [.15, .31]). For each of the analyses, the direct effect of religiosity on the foundation was non-significant after accounting for the indirect effect through MFDA. Thus, perceiving morality to be founded on divine authority fully mediated the relationship that religiosity has with the “binding” foundations in our American sample.

Figure 1: Endorsement of divine command theory mediated the negative relationship religiosity had with the “binding” moral foundations (Study 2). MFDA = Morality is Founded on Divine Authority scale. Total effect in parentheses. *** p < .001.

We ran similar mediation analyses with political conservatism as the independent variable. While MFDA was a significant mediator for all three binding foundations (95% CIs, sanctity [.22, .37]; loyalty [.03, .15]; authority [.07, .20]), the direct effect of conservatism on the foundations remained significant (ps < .01), revealing that believing that morality is founded on divine authority only partly mediated the relationship conservatism has with these “binding” foundations.

3.3 Discussion

Study 2 once again replicated the negative relationship between religiosity and utilitarianism, this time measured using naturalistic dilemmatic scenarios. This indicates that religiosity does not just predict deontological judgments in the abstract (“It is never morally permissible to lie”), but it also does so in the context of specific, naturalistic decisions (“I should not lie about my friend’s appearance to protect her feelings”). Moreover, this association between religiosity and deontology was fully mediated by religious individuals’ greater endorsement of DCT, as measured by our MFDA scale.

The MFDA was uniquely associated with non-utilitarian responding, even when statistically controlling for other relevant variables, such as social class, beliefs about why moral rules exist, and individual differences in moral foundations, variables that played only a small role at most. This suggests that MFDA is not just acting as an imperfect proxy for some other belief about morality, which speaks to the discriminant and construct validity of the scale. On the basis of Study 1’s results, it could be hypothesized that MFDA was simply a proxy for respect for authority in general as a morally important attribute, or that it was a proxy for a belief in the inadequacy of human judgment or the inherent corruptness of human nature. Study 2 has ruled out both of these possibilities. A belief that morality is founded on divine moral authority appears to be the critical mediator of the negative relationship between religiosity and utilitarianism. It seems that one’s beliefs about the ultimate foundation or source of morality are at least as important in predicting downstream moral judgment as the domains of morality that one endorses.

4 General discussion

The present studies provide an answer to the question of why religious individuals exhibit an aversion towards utilitarian moral thinking. Our findings indicate that a belief that morality is founded on divine moral authority, as opposed to human reason or intuition, is the part of religiosity that promotes deontological moral judgments. In Study 1, we developed the Morality is Founded on Divine Authority scale (MFDA), the first psychometric instrument designed specifically to measure endorsement of Divine Command Theory (DCT). MFDA showed good convergent validity, correlating with established measures of religiosity, and discriminant validity, correlating weakly, if at all, with theoretically unrelated aspects of personality. Moreover, MFDA fully mediated the relationship various measures of religiosity had with a non-utilitarian response style, including measures related to religious identity, belief, and practices. Study 2 provided further evidence that endorsement of DCT is the critical mediating variable by again showing that MFDA fully mediated the relationship between religiosity and utilitarianism, this time measured via discrete judgments in response to several naturalistic moral dilemmas. Study 2 also showed that the relationship between MFDA and non-utilitarianism is not accounted for by religious individuals’ greater concern with respecting authority in general, rather than God’s moral authority in particular, or their endorsement of the belief that deontological rules are necessary to prevent people from making flawed moral choices. Our results converge on the conclusion that a belief in God’s moral authority is a key variable that accounts for the association between religiosity and a rejection of utilitarian morality observed in previous studies. Furthermore, this research complements other recent work on meta-ethical beliefs (e.g., Goodwin & Darley, Reference Goodwin and Darley2008, 2012) by further illuminating the important role these beliefs play in guiding folk moral judgments.

4.1 Divine Command Theory and Moral Foundations

Study 2 demonstrated that the association between religiosity and deontology is not explained by religious individuals’ greater concern with the foundations pertaining to Ingroup loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity posited by Moral Foundations Theory (MFT). Quite the contrary, MFDA fully mediated the association between religiosity and endorsement of these so-called “binding” foundations. It has been suggested that religious individuals are more group-oriented, and therefore are more likely to view issues of Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity as relevant to their moral judgments (Graham & Haidt, Reference Graham and Haidt2010). Our results suggest, instead, that the meta-ethical belief that morality is founded upon God’s moral authority is sufficient to account for the association between religiosity and endorsement of the “binding” moral foundations, at least within our American sample. We believe these mediational results reflect the fact that holy texts (e.g., the Bible or Qur’an), which are perceived by believers to contain the revealed will of God for moral living, cover a wide range of topics, including those pertaining to group loyalty, respect for authority, and sexual/bodily purity (see earlier references). Insofar as these foundations are mentioned in holy texts as being important to moral living, a divine command theorist would accept them as valued principles and, accordingly, prioritize them within their everyday moral judgments.

Of course our findings do not explain how religious faiths and communities themselves come to prioritize these concerns (i.e., how these topics find their way into religious texts in the first place); they only help illuminate the vehicle by which religious adherents in American society might come to prioritize them. Though we have not ruled out a “social function” or group-orientation account for this difference in moral values, we have shown endorsement of DCT to fully mediate the relationship between religiosity and the binding foundations, and while it is possible that being group-oriented is really what drives people to endorse DCT, we find it unlikely. Still, further research is needed to directly test the social function account proposed by Graham and Haidt (Reference Graham and Haidt2010), and contrast it with our alternative account, as well as to rule out other untested third variables. There is certainly a complex mesh of interactive factors underlying belief in God and DCT—some of which may involve group-level processes. Suffice to say, our results regarding the relationship between political orientation and moral foundations in Study 2 (MFDA only partially mediated the relationship) leaves open the possibility that a social function account may be required to help differentiate folk morality along the political spectrum.

More broadly, our results speak to the importance of people’s meta-ethical beliefs in motivating their moral judgments. Lay beliefs about meta-ethics are under-studied in psychology. Nevertheless, as our results attest, it appears that moral judgments can sometimes be better predicted by people’s beliefs about the nature of morality—specifically, whether moral truths originate with God or may be obtained via human reason—than by the content of their moral codes, since in Study 2 we found MFDA to uniquely predict deontological judgments, whereas differences in moral foundations did not. Thus, lay meta-ethics has the potential to be an exciting and important topic of research in the future.

4.2 Limitations and future directions

Perhaps the largest and most obvious limitation is that our sample consisted entirely of Americans, and the vast majority of our religiously-affiliated participants were Christians. This obviously limits the generalizability of our findings to other religions, such as Hinduism or Buddhism. Nevertheless, we focused on Western religions, and Christianity in particular, for three reasons. First, we thought that avoiding cultural heterogeneity in our sample would diminish the potential for unobserved third variables (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism) to creep in and reduce the internal validity of our results. Second, prior research that has established the relationship between religiosity and non-utilitarian thinking (e.g., Piazza, 2012; Piazza & Sousa, Reference Piazza and Sousain press) was conducted primarily with Western (U.S. and UK), largely Christian samples. It has not yet been established whether this relationship exists in other cultures and religions, and our aim here was to explain the relationship shown by prior studies, not to test its generalizability to other cultural milieus. Finally, expressions of DCT are quite prominent in the holy texts of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (see references in section 1.2), while they are less prominent in Eastern religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism. Indeed, many branches of Buddhism are non-theistic (e.g., Zen); furthermore, many Eastern, pantheistic religions often preclude the possibility of a moralizing, high God, who issues moral commands and demands obedience (though see Baumard & Boyer, in press, for possible exceptions). Therefore, if the zero-order relationship between religiosity and deontological thinking does generalize to Eastern religions, we might not expect endorsement of DCT to be the critical mediating variable in those cultures, though we would expect this to be the case for Jews and Muslims, who share this feature in common with Christians. Cross-cultural research on the relationship between religiosity, DCT, and utilitarian thinking is obviously an interesting and important direction for future research.

Another limitation of the present work is that it is cross-sectional (rather than longitudinal) and correlational. Therefore, we cannot definitively establish whether endorsement of DCT causes people to resist utilitarian thinking, or whether a preexisting deontological thinking style predisposes people to endorse DCT. While both of these causal links are plausible, we believe the former is more likely in naturalistic settings given that aspects of DCT (such as God being supremely wise and just and the source of all things) are explicitly taught by religious institutions across America and are embodied in religious doctrine (e.g., see the Apostles Creed and Nicene Creed), while deontological ethics are probably less explicitly transmitted through religious teaching (though see the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Part Three, Article 4 “The Morality of Human Acts,” with regards to certain acts being inherently evil independent of their consequencesFootnote 8) and less essential to religious faith; that is, one can be a deontologist on non-theistic grounds (see Gert, Reference Gert2004; Kant, Reference Kant1785/1964).

4.3 Conclusion

The present research aimed to clarify the well-established negative relationship between religiosity and utilitarian moral thinking. This association appears to a great extent attributable to religious individuals’ endorsement of God’s moral authority, as measured by our novel MFDA scale. This research demonstrates the importance of understanding the role of meta-ethical beliefs in shaping moral judgment over and above the role of individual differences in moral foundations. Beliefs about what makes an act right or wrong—for example, whether or not God has issued a command obligating or forbidding acts of a certain kind—may be just as important to people’s moral judgments as the specific features of an act, its consequences, or the domain of behavior it may belong to.

Appendix A Scales used in Study 1 not provided in text

Consequentialist Thinking Style scale

Below are a number of different actions a person can perform. Please indicate your moral position concerning each action. Please read each option before selecting the one that best represents your position.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on killing? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to kill someone.

-

2. If killing someone will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to kill that person.

-

3. If killing someone will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to kill that person.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on assisted suicide or voluntary euthanasia? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to assist someone in ending their life.

-

2. If assisted suicide will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to assist someone in ending their life.

-

3. If assisted suicide will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to assist someone in ending their life.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on abortion? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to have an abortion.

-

2. If an abortion will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to have an abortion.

-

3. If an abortion will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to have an abortion.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on torture? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to torture someone.

-

2. If torture will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to torture someone.

-

3. If torture will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to torture someone.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on lying? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to lie.

-

2. If lying will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to lie.

-

3. If lying will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to lie.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on stealing? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to steal.

-

2. If stealing will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to steal.

-

3. If stealing will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to steal.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on incest? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to have sexual relations with a family member.

-

2. If incest will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to have sexual relations with a family member.

-

3. If incest will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to have sexual relations with a family member.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on cannibalism? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to eat the flesh of a dead person.

-

2. If cannibalism will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to eat the flesh of a dead person.

-

3. If cannibalism will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to eat the flesh of a dead person.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on betrayal? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to betray someone.

-

2. If betraying someone will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to betray that person.

-

3. If betraying someone will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to betray that person.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on deception? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to deceive someone.

-

2. If deceiving someone will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to deceive that person.

-

3. If deceiving someone will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to deceive that person.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on malicious gossip? (Select one)

It is never morally permissible to gossip about a person.

If gossip will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to gossip about a person.

If gossip will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to gossip about a person.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on breaking promises? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to break a promise.

-

2. If breaking a promise will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to break a promise.

-

3. If breaking a promise will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to break a promise.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on breaking the law? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to break the law.

-

2. If breaking the law will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to break the law.

-

3. If breaking the law will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to break the law.

Which of the following statements best characterizes your position on treason? (Select one)

-

1. It is never morally permissible to betray your country or defy governing authorities.

-

2. If betraying your country or defying governing authorities will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally permissible to betray your country or defy governing authorities.

-

3. If betraying your country or defying governing authorities will produce greater good than bad consequences, then it is morally obligatory to betray your country or defy governing authorities.

Attitude toward Religion scale

-

1. Religion is for people who can’t think for themselves.*

-

2. One important benefit of religion is that it provides people with comfort during hard times.

-

3. Religion only serves to increase tensions and hostility between groups of people.*

-

4. There is little good that comes from religion.*

-

5. Religion makes most people better than they would be otherwise.

-

6. There are some important lessons to learn from religion.

-

7. Religious teachings espouse ideas that are out of date and have little relevance to modern life.*

-

8. One positive aspect of religion is that it helps bond people together.

-

9. Without religion a lot more people would act selfishly and care little about others.

-

10. All things considered, religion has caused more harm than good for the world.*

-

11. Modern scientific knowledge makes religion unnecessary.*

-

12. Religion mostly promotes tolerance and compassion.

* Reverse-scored. Assessed in terms of level of agreement (1 = Strongly disagree; 9 = Strongly agree).

Short Christian Orthodoxy scale

-

1. Jesus Christ was the divine Son of God.

-

2. The Bible may be an important book of moral teachings, but it was no more inspired by God than were many other such books in human history.*

-

3. The concept of God is an old superstition that is no longer needed to explain things in the modern era.*

-

4. Through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, God provided a way for the forgiveness of people’s sins.

-

5. Despite what many people believe, there is no such thing as a God who is aware of our actions.*

-

6. Jesus was crucified, died and was buried but on the third day He arose from the dead.

* Reverse-scored. Assessed in terms of level of agreement (1 = Strongly disagree; 9 = Strongly agree).

Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire

-