Well, I can be cruel

But let me be gentle with you.

Joni Mitchell, “The Gallery,” Clouds, 19691

The release of a new album by 76-year-old Joni Mitchell on October 30, 2020—13 years since she released her last studio album, Shine—must have come as a surprise to those without the anticipation of dedicated fans. It seems fair to call those fans its target audience: The album consists of a five-disc boxset of recordings from the mid-1960s, which predate Joni's first record deal.Footnote 1 Although snatches of her performances during these years of budding musical professionalism have been released previously, nothing of the scale and scope of Joni Mitchell Archives—Vol. 1: The Early Years (1963–1967) has entered the domain of public consumption before.Footnote 2 Perhaps it is only natural that this relative inaccessibility has traditionally gone hand in hand with a tendency to look past these years within the pages of published scholarship and popular biography. Until now, there has been little musical material to work with, and Joni's many studio albums that date backward from Shine in 2007 all the way to Song to a Seagull in 1968 offer more than enough recorded music for those wishing to examine her artistry. The same can be said of recent biographies, or quasi-biographies, often written in conjunction with her, which elide her early years often for the simple reason of historical distance. What accurate information we have about Joni's life in the 1960s is relatively limited, as is what she can remember with precision half a century later, and that, of course, is fair enough.Footnote 3

But there is little overstating the enormity of these early, pre-studio album years in Joni's life. By the summer of 1965, aged twenty-one, Joni had become pregnant while living in Calgary; moved to Toronto under duress of unspoken shame; was abandoned by the child's father; became a single mother; married a man (Chuck Mitchell) she barely knew; and moved once more to Detroit. The marriage turned toxic before long, she made the painful decision to place her baby for adoption and, in early 1967, she separated from Chuck and embarked upon her solo career as a singer-songwriter in New York City. When centered like this, these details are shocking in their largely anonymized cruelty and shadowy patriarchy; they seem irrefutably to demand proper and sensitive consideration, unconsignable to introductory preamble or glorified footnote. It is no wonder that Joni has since referred to this time in her life, 1965–67, as “this three-year period of childhood's end.”Footnote 4

Within this turbulence, Joni wrote some of what would become her most celebrated original songs. They pepper her first four albums between 1968 and 1971, and they bear the scars of steep learning curves and formative moments of earlier years. Many would never be selected for the prestigious role of appearing on one of her studio albums, including the song “Urge for Going,” which Joni released as a B-side to “You Turn Me On, I'm a Radio,” her lead single from her 1972 record, For The Roses. But Joni wrote this song 7 years earlier, in 1965, and there are plenty of other recordings of her performing it in the mid-1960s as she made a name for herself frequenting the hottest folk venues and coffeehouses across North America. Three of these appear on Joni Mitchell Archives, but there are, in fact, many other performances of “Urge for Going”—at least a dozen, quite possibly more—that were recorded during these 3 years. Many took place in coffeehouses, others at larger venues, some in studios, and a couple are accompanied by video material.

These recordings are entangled with a transformative period in Joni's life, and “Urge for Going” serves as a kind of touchstone for how her musicianship developed and matured in these years of catalytic change. In this article, I want to meditate on these three important but underexamined years (1965–67) as refracted through Joni's music. To be more specific, I want to contextualize and trace the emergence of Joni's quite complicated relationship with the idea of freedom—as a goal, as a state of being, as a state of mind—in dialogue with her evolving interpretation of this one song, “Urge for Going.”

All of this requires decentering the studio album as a musicological line of inquiry and focusing instead on live performances and non-album recordings. But there is another issue at play which I should address first, because within popular music studies, to explore an entanglement like the one I'm suggesting is immediately to enter troubled waters. One of the most persuasive paradigms for understanding what popular musicians do is through the notion of the musical persona. In Philip Auslander's words, “when we see a musician perform, we are not simply seeing the ‘real person’ playing … When we hear a musician play, the source of the sound is a version of that person constructed for the specific purpose of playing music under particular circumstances.”Footnote 5 In this formulation, an awareness of potential layers of artifice in the performer's self-presentation is paramount. These kinds of layers are obvious in some instances—such as “in performances by flamboyant rock stars”—and less so in others; but “even self-effacing musicians, such as the relatively anonymous members of a symphony orchestra … perform musical personae.”Footnote 6

When formulated inclusively, this kind of model allows a performer's self-presentation to be understood as entirely fictional, or representing how they really feel, or perhaps somewhere in between. But Ross Cole has recently argued that, in practice, this is not how musical personae have been conceptualized by scholars. Linking Auslander's work back to that of Simon Frith (and more broadly to trends in Francophone post-structuralism), Cole has argued that persona theory “downplays the ‘real person’ to such an extent that they disappear behind a veil of sociology and spectacle.”Footnote 7 It steers us into a mode of listening where “what we hear in popular song is not honest personal confession, but a staged process of identity formation and performative masquerade in which a singer actively responds to the demands of an audience, whose members invest (both emotionally and financially) in a celebrity persona that may bear very little relation to the person behind the mask.”Footnote 8

One consequence of this is the tendency to view a musician's “real” identity and their staged persona as cleanly separable, “neat demarcations” which Cole has called “unprofitable to draw and follow.”Footnote 9 David R. Shumway's take on Joni's persona is a good example of this. He writes that

singer-songwriters may seem to lack star personas altogether or to manifest ones that are indistinguishable from their private selves. It is one of my tasks to show how this experience of direct address is produced; my assumption is that the Joni Mitchell the songs reveal is as much a performed role as is Mick Jagger's, Bob Dylan's, or even Brian Ferry's, and that would be true regardless of the singer's intentions.

One of the most powerful characteristics of Mitchell's persona, then, is honesty. There is, of course, a paradox when Mitchell—or, I would argue, any artist—successfully conveys honesty and makes her audience believe that they are being directly addressed. The implication of this belief is that that persona and self are identical; that in other words there is no persona. But even though we may accept that in “River” it is Mitchell herself who is “selfish and sad,” we as fans can only add that information to our understanding of the Joni Mitchell star persona, since we cannot know the private person. However, the conviction that the songs are true may encourage many to believe that they can know the real Joni, increasing the “tension between the possibility and impossibility of knowing the authentic individual” and making them look all the harder for the missing information that they hope will relieve it. What such listeners fail to understand is that this tension is a necessary condition of the star system and of fiction.Footnote 10

Shumway is writing about Joni around the release of Blue in 1971, at which point she had already achieved musical stardom and become embedded in the landscape of American celebrity popular culture. In other words, this is a moment at which it is especially worth seeking out the performative qualities of Joni's “honesty,” as he does, but the circumstances are quite different when we consider her earlier years. I can illustrate the point with one of Joni's first originals, the song “Born to Take the Highway,” an early performance of which came at The Wisdom Tooth coffeehouse in Detroit on November 15, 1966. She introduces the song to the audience by apologizing for its idealistic, even utopian view of travel:

Well, there's a reason that this song is kind of idealistic and a little bit on the schmaltzy side, and that is because I wrote it before I ever travelled any place, and since I began to travel a lot I've found that I have had some hard times of my own—for instance, one time I was on a flight between Chicago and Detroit and the stewardess gave me a lumpy pillow. And then there was another time when I'd asked for a pillow and they'd run out. And that was pretty awful. But actually, I really haven't seen too many troubles.Footnote 11

Between this backstory and the bright-eyed and bushy-tailed lyrics, there is no reason to doubt the idealism behind the song. The imagined halcyon days of life as a young, traveling musician lay before Joni as she composed it on the highway between Toronto and Detroit, and it offers a good example of Cole's suggestion of “hearing particular songs as acts of autobiographical making.”Footnote 12 But having survived polio as a child, been abandoned as a young pregnant woman, and lived as a single and poor mother, experiences of hardship certainly lay behind her, too. Probably nobody attending this gig would have known any of this, and most would have taken her vignette at face value, but as Joni later recalled to Malka Marom:

I'd come through such a rough, tormented period as a destitute, unwed mother. It was like you killed somebody, in those times. It was very, very difficult. I ran into people behaving very cruelly, ugly. I saw a lot of ugliness there. They experimented on me in the hospital. No one to protect me. So I had, in fact, seen quite a bit of the “I've looked at life from both sides now.” I had some serious battles for a twenty-one-year-old.Footnote 13

So when Joni says that she hasn't seen too many troubles, she is performing a kind of wholesome, innocent rural purity—a folk persona whose life exemplifies simplicity. In reality, Joni's first 21 years held no shortage of hardship, even if that is not something she discloses on stage. “Born to Take the Highway” captures a self-constructed, autobiographical truth—her pressing desire for escape and excitement for travel—which is partially shrouded in folk mystique, at least in this performance.

Bringing other songs into the mix further complicates things. In the same years as she was performing this persona, Joni also wrote and performed her song “Little Green.”Footnote 14 “Little Green” is Joni's pseudonym for her daughter; it is her most concentrated early effort to give musical expression to the heartbreak of parting with her new-born baby:

It was not until much later that the existence of Joni's daughter became public knowledge, and Joni's audience that night would have been none the wiser: In the words of David Yaffe, “Little Green” is a song in which Joni tells all but reveals nothing.Footnote 15 To neglect the complicated admixture of catharsis and pain that must have been interwoven into Joni's private experience of writing and performing this song would be to fail to do justice to Joni Mitchell the performing musician. It would also mean failing to treat her as a real human being who has dealt with real pain.

In this article I seek a more trusting approach to Joni's early work, by which I mean that I intend to avoid the skepticism that Cole detects in persona theory. I remain open, at least in principle, to the possibility that a musician's songs, or performances of songs, can constitute honest self-readings or reflections on their life. That is my issue with adopting Shumway's model: By collapsing together the idea of “honesty”—broadly construed—with an inaccessibly ethereal formulation of the “authentic individual,” it is easy to brand a trusting approach as naïve. Persona theory guards the scholar against being duped, but if taken dogmatically its critical impulses can veer into the unwavering suspicion of what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick has called “paranoid readings.”Footnote 16 William Cheng has pointed out just how elemental paranoid readings have become to the musicological condition: “By actively mining for threats in the world,” he writes, “practitioners of paranoid readings rarely fail to unearth the truths that they are chasing. With seductive rhetoric and logic, they produce self-satisfying critiques, which in turn affirm, after the fact, that no one can ever be paranoid enough.”Footnote 17

Sedgwick's “reparative readings,” committed more to pleasure and amelioration than exposure, offer an alternative.Footnote 18 It is a guiding idea behind Ruth Charnock's edited volume on Joni, in which Charnock points out the benefits of reparative listening and care.Footnote 19 Indeed, in a new disciplinary-rallying cry, Cheng re-envisions “musicology as all the activities, care, and caregiving of people who identify as members of the musicology community,” one built in turn on an ethics of care which is drawn especially from several important feminist thinkers, including Eva Feder Kittay and Virginia Held.Footnote 20 Yet, as he notes, care “remains weirdly radical, a sentimental outlier against normative critical impulses.”Footnote 21 One reason lies in misplaced preconceptions of the limits of care, namely that it belongs in the home of the nuclear family, firmly associated with motherhood. But Held has argued instead that “caring relations extend well beyond the sorts of caring that takes place in families and among friends, or even in the care of institutions of the welfare state, to the social ties that bind groups together, to the bonds on which political and social institutions can be built, and even to the global concerns that citizens of the world can share.”Footnote 22

Cheng is especially concerned with how musicologists treat their peers and their students; perhaps we can also exercise more compassion for the musicians we study.Footnote 23 What would it look like not to shy away from or minimize the harsh realities of Joni's early adulthood, to try to uphold its emotional costs as important and worthy of musicological inquiry? As an alternative to the criticality of persona theory, in this article I sketch an approach which adopts an intellectual disposition of care. It is not because Joni is a woman and somehow therefore more inherently needing of care, but because it is through a disposition of care that such emotional costs can be framed and taken seriously from a scholarly standpoint. It also allows a more permeable and messy relationship to emerge between Joni's life experiences and musical imagination. Sedgwick has written that “it is only paranoid knowledge that has so thorough a practice of … masquerading as the very stuff of truth.”Footnote 24 “Truth and care,” on the other hand, seem to “pose a false yet stubborn dichotomy in intellectual pursuits,” as Cheng puts it.Footnote 25 To paraphrase him, I would like to try to find truth in care instead of skepticism.Footnote 26

2

Musicologists can feel uncomfortable with displays of affection in their work. As Cheng puts it, they often “expertly sublimate their affections through histories, ethnographies, and analyses that show an undeniable love of music…while brushing away the need to say the embarrassing L-word outright.”Footnote 27 That L-word is of course love, and it is possibly a quirk in the system that many studies of Joni Mitchell wear their hearts on their sleeves, proclaiming their fandom more unashamedly. Charnock has recounted some of the personal moments that scholars have disclosed, many involving scenes of “the authors listening as a child or adolescent.”Footnote 28 She also points out the stigma attached to certain kinds of listening, especially evident in apologetically couched accounts of teenage girl discovery, part of what she calls “a long roster of critics who denigrate female listening”:

It's the tone of a woman feeling that she has to do the work of legitimizing what she loves, as if loving it isn't legitimacy enough, while also anticipating the ways in which this love will be trashed: as unoriginal, as romantic, as solipsistic, as immature, as too personal, as—let's just say it—too feminine: girl's stuff.Footnote 29

These kinds of experiences are often shaped around a particular studio album. For Anna Karppinen, it was Song to a Seagull, Joni's first album, which struck her as “not just a good first album by a fledgling singer-songwriter: it was a collection of extraordinary songs, all of which spoke to me in a way I had rarely encountered before.”Footnote 30 Brian Lloyd recalls being given For the Roses as a freshman in college and spending “the next several months listening intensely to that album—every night after homework was done, headphones on, suitably stoned.”Footnote 31 Many, including Yaffe and Michelle Mercer, cite Blue as their defining Joni experience.Footnote 32 Charnock does too, and she fondly remembers being given a ripped copy of Blue by one of her friends the day after her twenty-first birthday party, most of which she missed because she got so stoned that her friends had to put her to bed early.Footnote 33

So it fits that most studies of Joni's music revolve around the album concept. Lloyd Whitesell's book remains the most extended example of this, in which he groups Joni's work “into four distinct periods, defined according to the studio albums released between the following dates: 1968–1972 (five albums), 1974–1979 (five albums), 1982–1988 (three albums), and 1991–1998 (three albums).”Footnote 34 In her book, Karppinen pays special attention to Joni's first nine records and points to the importance of the album format within Joni's musical auteurship. (After her first album, she was heavily involved in producing her own music, while album covers were often her own artistic work.Footnote 35) Charles Ford, following Whitesell, focuses on Joni's “early style” by analyzing her first five studio albums.Footnote 36 Others limit themselves to a selection of songs from one album, like Lloyd with For the Roses, or to a single song from an album, such as Charles O. Hartman in his analysis of “Michael from Mountains,” or simply to one album, as Sheila Whiteley does with Blue.Footnote 37

Whiteley frames her discussion of Blue within the context of 1960s counterculture, a “generic label for a somewhat loose grouping of young people, a generational unit, who challenged the traditional concepts of career, family, education and morality and whose lifestyle was loosely organized around the notion of personal freedom.”Footnote 38 This certainly comes through in Blue, in which Whiteley hears “a tension between freedom and dependency.”Footnote 39 She points out that the opening song, “All I Want,” demonstrates Joni's awareness “that the ‘road’ will be problematic, but equally [that Joni is] certain that it provides ‘the key to set me free.’” But Blue was released in 1971, and we don't need to look that far ahead to detect the prevalence of this notion of freedom. It is often highlighted as a theme in her debut record, Song to a Seagull. Karppinen writes that, in Song to a Seagull, Joni moves “towards a more adventurous way of life—associating with unpredictable men and longing for the absolute freedom of flight.”Footnote 40 She argues that “Song to a Seagull, despite following on the heels of the break-up of her marriage, is not a ‘divorce album’ as such. Although there is an undercurrent of melancholy … the overall tone of Seagull is that of hope and dynamic movement.”Footnote 41

For many scholars, “Cactus Tree”—the last track on the album—epitomizes this sense of freedom. Karppinen argues that it “stands in direct opposition to the kinds of songs women were expected to sing in the sixties. Instead of waiting demurely for her one true love, or pleading for his attention and the all-important diamond ring, Mitchell delivers a frank but kind-hearted report of the many men she had met.”Footnote 42 Likewise, Marilyn Adler Papayanis notes that it “is not about the freedom to sleep around (though this is certainly an important aspect of being free) but, rather, the freedom, always the privilege of men, to live for herself.”Footnote 43 Whitesell writes that “personal freedom” is of “absolutely central importance” to Song to a Seagull given how the album is bookended, but his interpretation of that freedom is less straightforward:

The opening song, “I Had a King,” relates the protagonist's escape from a suffocating marriage; the closing song, “Cactus Tree,” evokes the more spacious horizons, as well as the emotional costs, of her ongoing quest. The two scenarios stand for the two poles she is compelled to negotiate in her search for self-fulfillment: the perils of domesticity and the perils of rootlessness. By countering the irresistible, open-ended urge for independence with a difficult, unresolved yearning for love, Mitchell sets up a lasting internal controversy at the core of her musical expression.Footnote 44

Whitesell suggests that Joni's idea of freedom is a troubled one, that independence in its purest form is no nirvana. Like Papayanis, he links this to romantic love, a nod to Joni's fleeting relationships in the aftermath of her divorce from Chuck. That there might be something larger at play is picked up on by Peter Coviello:

“Cactus Tree”…brings to its first full expression less an idle embrace of “freedom,” that keyword of the era, than a wrought, mistrusting, precisely calibrated ambivalence about the promises of that freedom, particularly as it had come to be routed through the gendered idioms of 60s-left cultural radicalism.Footnote 45

What Coviello is getting at here is something that Whiteley has discussed in detail.Footnote 46 Although the 1960s counterculture movement reflected “a growing recognition that a political system which perpetuated inequality and a general lack of freedom was untenable,” it nevertheless continued to exclude and subjugate women.Footnote 47 As Whiteley writes, “the lifestyle and the musical ethos of the period undermined the role of women, positioning them as either romanticised fantasy figures, subservient earth mothers or easy lays.”Footnote 48 In a period of folk revival when music was considered to be saying things of cultural and political importance, “women performers were largely viewed as ineffectual, as entertainment.”Footnote 49 Audre Lorde made the point more generally when she spoke of “the dangers of an incomplete vision”: Looking back, she commented that “if there is one thing we can learn from the 60s, it is how infinitely complex any move for liberation must be,” there being “no simple monolithic solution to racism, to sexism, to homophobia.”Footnote 50

This is to say that Joni's reflections on freedom seem not only to unsettle the hegemony of the monogamous romantic relationship, but also to speak to the everyday inequality of women in society at large. About “Cactus Tree,” Coviello has put it more eloquently than I could hope to in his discussion of the song's “central preoccupations, which are of course ‘freedom’ and the way it circulates in what the song names, at the very outset, ‘a decade full of dreams’”:

It is a relation that, for Mitchell, is not at all simple or self-evident. Indeed, it is precisely the wrought-up, articulate tension that the song nurtures and sustains in relation to an idea of “freedom” that makes it both the early-career powerhouse that it is, and something of a Rosetta stone for the whole of the career that was to follow. For Mitchell is of course invested in, attracted to, and not unbeguiled by prospects of freedom, even when they speak in idioms somewhat worryingly sententious; but in her persistent ironizing of those languages, her undercutting leaning against them, she registers as well a far-sighted misgiving about what “freedom” can and will mean in the contexts in which it circulates—especially for women.

The song invites us to see that “Cactus Tree” is a shimmering distillation, less of Mitchell's youthful and ardent poeticism, than of her fierce and unsparing ambivalence: a testament, in all, to what would become for her, over many years and many records, a habitual resistance to “freedom” itself, in the offered registers, especially as they entangle the sexual and the political.Footnote 51

This freedom is mature, layered, complex, and a long way from the optimism of “Born to Take the Highway” as Joni may have first sung and played it on the road from Toronto to Detroit in early 1965. But how have we got here? Song to a Seagull was released in 1968, toward the end of the “decade full of dreams” of which she sings in “Cactus Tree.” Joni's early years seem key in this respect: To make sense of this freedom that so many scholars have thoughtfully highlighted we need to see Song to a Seagull not as a starting point but as one of many stars in the constellation of Joni's music, a constellation that precedes and exceeds her studio discography. And to do this, we need to go back to 1964 when Joni stepped out into Toronto to begin a new chapter in her life.

3

Cameron Crowe: Can we say “Urge For Going” is a song that felt like a kind of beachhead for you?

Joni Mitchell: I think so. I think it's the first well-written song that I have. I felt it was well-written. Memories of summer's end and winter coming on. Just what the song says, you know? And a desire to escape that cold period. Footnote 52

Joni recalls that she had sixty dollars to her name when she arrived in Toronto, where she rented an attic flat for fifteen dollars a month, the cheapest she could find.Footnote 53 She had become pregnant at the age of twenty with her then boyfriend Brad MacMath while studying at art college in Calgary. It wasn't long before MacMath abandoned her and bailed to California, and Joni saw out the remaining months of her pregnancy alone, too consumed with guilt to reveal the truth to her parents.Footnote 54 In her words (as I quoted above), an unplanned pregnancy was akin to having killed somebody. Aged twenty-one, she gave birth to a baby girl, Kelly Dale Anderson, on February 19, 1965.Footnote 55 Although Kelly Dale was placed in a foster home, it would be months before Joni finally signed the adoption papers. In April, she met Chuck Mitchell while performing at the Penny Farthing, a coffeehouse in Toronto.Footnote 56 They got married a mere 2 months later, on 19 June, and moved to Detroit in what Joni later described as “an attempt to keep [her] child”; eventually, she made the painful decision to relinquish her parental rights.Footnote 57

It was in Detroit that the folk duo of “The Mitchells” began, and Joni and Chuck started to frequent the city's coffeehouses, taking up a residency at The Chess Mate at Livernois & McNichols in July.Footnote 58 In August, Joni became a late addition to the Mariposa Folk Festival in Caledon East, Ontario, her first major appearance before a large audience.Footnote 59 She recalled in an interview in 1968 that she thought that she had “bombed”: “I didn't have much variety. I wasn't very good, but had a lot of trouble with the audience booing and hissing and saying ‘Take your clothes off, sweetheart.’”Footnote 60 On her way back from the festival in the car, feeling like quitting the music scene, Joni scribbled down the line “It's like running for a train that left the station hours ago/I've got the urge for going but there's no place left to go.” She rediscovered it later when clearing out her guitar case and used it as the seed for the song “Urge for Going”: “I wrote that [line] in August, and the next thing I knew it was September, and then October. I was really cold, and I was saying ‘I hate winter and I really have the urge for going someplace warm,’ and I remembered that line. So I wrote ‘Urge for Going’ as it now stands, from that.”Footnote 61

That gives us October 1965 as a possible date for the song's completion. Joni made one of the earliest currently available recordings of it in her Detroit flat, perhaps that month, as part of a tape for her mother's birthday which also contained early versions of “Born to Take the Highway” and “Here Today and Gone Tomorrow.”Footnote 62 “I've written a couple of new songs since we were out here,” Joni says at the start of the recording, “and I think you'll like this one especially, Mom.” She would later introduce the song more elaborately, like this:

It's a song that was inspired by the part of the country that I come from, a place called Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, which really isn't a disease although I've seen it in some medical journals. The Saskatoon itch and all that kind of stuff. You get that from picking Saskatoon berries.

In Saskatoon or in Saskatchewan—or on the prairies for that matter, that includes the American prairies—the winters and the summers are very radical, with the temperature varying as much as 150 degrees in a season. So when the winter sets in, it really sets in, and drops down to about 50 below and all the people sit around and complain a lot, but they never really do anything about it. Some people think that they're frozen stiff, but that's not really true. They just complain and say, “I wish I was in Florida,” and the farmers and the people who are wealthy enough do go down to Florida or some island for the winter. But then the rest of us poor old common folk up there have to sit and suffer through.

And that was what I had in mind when I wrote this song, but I think it means different things to different people. It's called the “Urge for Going.”Footnote 63

This introduction lends itself to quite a straightforward reading of the lyrics: The “trees shivering in a naked row,” the meadow grass “turning brown,” and the “bully winds” pushing the fallen leaves “face down in the snow” all conjure the image of a punishing winter onset in landlocked southcentral Canada.Footnote 64 Although desperate to leave, Joni is trapped within this seasonal repetition, while the other active characters in the story—her “man in summertime,” the “geese in chevron flight,” and summertime itself (personified as a woman)—succeed in escaping. Between this introduction and her 1968 interview, there are Janus-faced sentiments of entrapment and loneliness: on the one hand looking back to her previous life in Saskatoon, and on the other looking ahead doubtfully now that the folk movement she wished to be a part of had come and gone.Footnote 65 If “Born to Take the Highway” captures the initial, momentary optimism of Joni's musical journey, “Urge for Going” reflects the cyclic gloom that preceded it as well as the unmatched expectations that followed.

Joni's performance of “Urge for Going” on the “Myrtle Anderson Birthday Tape” is her fastest rendition of this song with a tempo of about 125 BPM.Footnote 66 There is a strict agility to her fingerpicking, a kind of perpetual motion, which is punctuated by treble, bell-like drone notes that ring out during verse and chorus. She sings with metric regularity, most of the lyrics’ stresses coming comfortably on the beat, and in her voice we hear a breathiness that signifies her youthfulness. But sonically, there is more to it than that: Her breathy vocal tone has the effect of marking the note onsets with a sharp attack followed by quick decay, one that enters into a dialogue with her plucking guitar style. Just as the perpetual motion of her guitar playing conveys a sense of forward motion, so she seems unwilling to linger on the note she has just sung, eager instead for the next word or phrase.

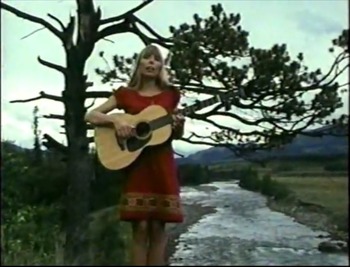

In June 1966, Joni and Chuck moved from Detroit to New York City and extended their range of coffeehouses beyond Michigan, performing at locations across North America.Footnote 67 One of Joni's engagements during this time involved making a studio recording and music video of “Urge for Going” for the Canadian television series Mon Pays, Mes Chansons on August 17.Footnote 68 Video recordings such as these are even more complex documents than audio recordings, with several invisible agents behind them, so it is especially important here not simply to attribute every creative choice to Joni. But the video complements her lyrics and playing in fascinating ways. It is shot in an unspecified location of natural, wild beauty in Canada.Footnote 69 As if liberated from everyday concerns, Joni wanders leisurely and aimlessly with her acoustic guitar among trees and against the backdrop of a mountainous Canadian vista. These natural allusions to independence and freedom are emphasized above all by the relentless movement of the flowing river, the gurgling sounds of which are dubbed over the recording and thus enmeshed sonically with Joni's song. Her bold red dress overshadows the greens and glassy reflections of the water, as if she is being purposefully likened to a single poppy in a field, or perhaps the prairie lily, the provincial floral emblem of her native Saskatchewan. Either way, it is a stereotypical depiction of rare and delicate femininity that suggests she is of and yet transcends her surroundings (see Figure 1). There is, then, a simultaneity at play here. Joni moves about as if untethered by the real world and yet still in search of freedom in its purest form, akin to the flowing of rivers or the flight of birds. She sits by the river's rapids, gazes wistfully into the distance, casts her eyes above at the “geese in chevron flight”: What she is looking for is out there, somewhere. Or perhaps more precisely, it is the excitement of being out there that she seeks (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Still from Mon Pays, Mes Chansons: Joni standing by the river.

Figure 2. Still from Mon Pays, Mes Chansons: Joni sitting by the river.

Joni's performance here is slower, at 116 BPM—the studio setting of this recording is possibly a contributing factor—but the song retains its energy through the added instrumentation: Joni is accompanied by a second, cheerfully melodious acoustic guitar part and a bass player. The inclusion of the bassline in particular adds buoyancy to this performance, sharpening the already spikey accents that punctuate each bar.

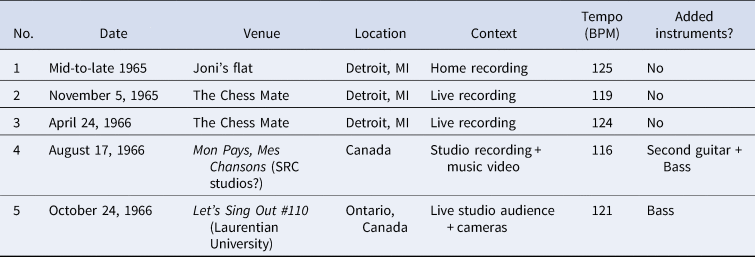

Table 1 groups together five early performances of “Urge for Going.” Broadly speaking, they all conform to the same general interpretative approach: The perpetual motion of the fingerpicking, the metric regularity of Joni's vocal phrasing, her breathy, detached vocal articulation, the consistently spritely tempo, and (where applicable) the added instrumentation all betray a sense of forward motion. In short, these are the features of what I am calling her idealistic interpretation. They put the urgency into “Urge for Going,” one shaped by a desire, most obviously, to escape the monotony of Saskatoon. Given that Joni composed the song in 1965—in other words, after her disenchanting debut at Mariposa and a few months into her marriage—that desire perhaps also stemmed from the lack of fulfillment her new life had so far offered her. In the same way that Joni's “Born to Take the Highway” captures an idealized sense of travel, so too does “Urge for Going,” in this formulation, long for an idealized notion of freedom.Footnote 70

Table 1. Five performances of “Urge for Going,” mid-1965–October 1966

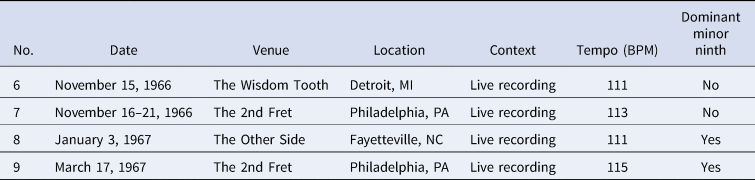

Between November 16 and 21, 1966, Joni took up a residency with Chuck at The 2nd Fret in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a coffeehouse that would welcome her back many times in the late sixties.Footnote 71 This gig came less than a month after her performance on CBC TV's Let's Sing Out #110 at Laurentian University, and yet the recording of “Urge for Going” from this residency captures quite a different interpretative strategy, one which can be found across other performances in late 1966 and early 1967 (Table 2).Footnote 72 It is not just that her tempo is slower (down to 111 BPM in some instances), although that is part of it, but also that she has changed her fingerpicking style: The perpetual motion of earlier renditions is replaced here with a lilting accompaniment, and the ringing bells of the treble strings are now subsumed into a much quieter, consistent overall dynamic. It seems likely that Joni has been influenced at least partly by Tom Rush's slower, brooding cover version of “Urge for Going” which he released as a single in October 1966, but the air of resignation creeping into this song is her own, expressed in a reflective and pensive tone absent from her earlier performances. All of this is heightened by a compositional change in the guitar part in the two later gigs, namely at The Other Side in Fayetteville, North Carolina on January 3, 1967 and The 2nd Fret on March 17, 1967. This change occurs at the brief two-bar transition between verse and chorus: Her performances up to this point have approached the downbeat tonic chord of the chorus via a dominant seventh, but in these performances Joni ratchets up the tension by adding in the flattened sixth note of the tonic scale, turning the chord into a dominant minor ninth.Footnote 73 This is a very subtle but hugely powerful difference, one which adds a layer of surprising anguish to the chorus and whose weighty dissonance seems disproportionate to the resolution that follows.

Table 2. Four performances of “Urge for Going,” November 1966–March 1967

Much can happen in the space of a year. Musically, Joni was not satisfied in her partnership with Chuck. “When Chuck … and I got married,” she remembers, “I kind of got sucked into music, compromised music because he wanted us to sing as a duo, and his choice of material would not be mine.”Footnote 74 Backstage at The 2nd Fret after their gig on November 17, they were interviewed by a reporter from the Philadelphia Daily News for an article that appeared the next day, portentously titled “Togetherness Not For This Couple.” The interviewer writes:

The husband-and-wife folk music team of Chuck and Joni Mitchell, at the 2d Fret, are unique among show business duos. They work alone in separate sets, but never sing side by side. “We're two altogether different types,” Joni explained. “And our voices clash when we work together.”Footnote 75

Joni would later say that “as soon as the duo dissolved, the marriage dissolved,” but their marriage problems ran much deeper than musical difference.Footnote 76 She told Yaffe that “Chuck Mitchell was my first major exploiter, a complete asshole,” as well as saying that:

My husband thought I was stupid because he had a BA in literature. … He took me on as a trophy wife. He liked my body, but he didn't like my mind. He was always insulting me, because he had the pride of the well-educated, which is frequently academic stupidity.Footnote 77

It is hard not to read these tensions into the Philadelphia Daily News article, an illuminating moment snatched from the twilight of their short, mismatched marriage. Belittling accusations of stupidity are the common theme of Joni's recollections of the marriage. “Chuck called me stupid a lot,” she told Marom: “I married into a hotbed of teachers and I only had a high school education, and I called children ‘kiddies,’ which is an Irish regionalism but it made me seem déclassé and, to him, stupid.”Footnote 78 It seems that her marriage to Chuck represented an example in miniature of the kind of contradictory sexist countercultural tendencies to which Whiteley has importantly drawn our attention.Footnote 79 David Crosby described him as “a guy who was using her and keeping her down. The guy was a talentless nobody who hooked on to a tremendously talented girl and married her to keep her in line and used her to have an act and make a living.”Footnote 80 With this in mind, the posters and flyers which bill Chuck and Joni's duo as “The Mitchells” seem uncomfortably possessive.Footnote 81

The hallmarks of this changing interpretative approach are captured across Joni's performances of this song in late 1966 and early 1967 (as described above and condensed in Table 2). There is no linear trajectory of change, but each performance evokes a more contemplative and less certain mood than before. In these gigs, and surely other ones around this timeframe, she is experimenting with and growing into a new feeling for “Urge for Going” at the same time as her folk musical duo is unraveling, and her stifling marriage increasingly coming apart at the seams.

4

The marriage hobbled into 1967. Chuck and Joni's final performance together came in May of that year, meaning that by the time Joni performed “Urge for Going” at Canterbury House in Ann Arbor, Michigan on October 27, 1967, she had entered a new phase of her life and career.Footnote 82 She was, at this point, living independently in New York, courting romances with the likes of Crosby and Leonard Cohen from the summer onward, and pursuing her aspirations as a solo artist.Footnote 83 Around this time, she composed songs which echoed her estrangement with the reality that had supplanted the world of travel she initially imagined: She conjured up the loneliness of “Marcie,” which Joni described as “a song about most girls who have come to New York City,” rebuked Chuck in “I Had a King,” and dealt with the trauma of giving up her child in “Little Green.”Footnote 84

Musically, her interpretation continued to evolve. At 104 BPM, this performance of “Urge for Going” is her slowest that I have been able to find from these years, and in many ways it consolidates the changing strategy I hear in the four performances listed in Table 2. The lilting quality of the guitar is even more pronounced than before, and the dynamics remain subdued throughout other than occasional swells. The most radical changes, however, are in Joni's voice. Her delivery of the lyrics is much more flexible and metrically supple—by way of example, her opening two lines, “I awoke today and found/the frost perched on the town,” abandon all on-the-beat regularity—and her vocal timbre has shed much of its breathiness in favor of a more supported, forwardly placed mixed voice. Her tendency to sing off the voice is replaced by the richer legato with which she sings through and sustains long notes and phrases, especially noticeable on her held notes at the end of each verse leading into the chorus. The anguished dominant minor ninth flares up at these points, too, in ways that lightly mirror the greater unpredictability about this performance in general: On its first appearance, she crescendoes through the two bars, but in subsequent iterations her voice almost disappears behind the guitar's gentle dissonance. She concludes with an extended but understated guitar postlude, the effect of which is to punctuate the end of the song with a musical question mark.

Joni's interpretation of this song in October 1967 is utterly different from the version she recorded in her flat for her mother's birthday in 1965. The perpetual motion, louder dynamics, and faster tempo of her earlier performances betray an impatience for the freedom she seeks, a freedom at that stage idealistically rooted in the promises of a new life in Detroit (or, at least, beyond Saskatoon), and based around what popular psychologist Tal Ben-Shahar would call an arrival fallacy—the false belief that reaching a valued destination can sustain happiness.Footnote 85 What I am sensing in this later performance is the disappearance of this impatience and the presence, instead, of the same ambivalence to freedom that Coviello hears in “Cactus Tree”; a song which, incidentally, Joni wrote that same month, and which she played at the same gig at Canterbury House.Footnote 86 “Urge for Going” amplifies Joni's ambivalence about freedom but it also, in its many manifestations, traces the emergence of that ambivalence musically; as one of her first originals, conceived alongside “Born to Take the Highway,” it straddles two phases of Joni's life that are worlds apart. In 1965, that highway was only imaginatively envisioned. By 1967, Joni had traveled thousands of miles on the roads connecting Detroit, Toronto, New York City, Philadelphia, and so many other cities reaching down the east coast of the United States and scattered across Canada. By the time of the gig in Canterbury House, she had accomplished everything the song seems to yearn for, and yet she sounds lonelier and less certain than before.

What has evolved instead is a much more complicated relationship with solo travel and musical vagabonding, as the reality of life as a traveling musician turned out not to be the utopia Joni may have hoped for. And that reality, of course, was one which was colored by a folk revival counterculture which espoused social liberation and equality, but which in practice continued to stifle and marginalize the voices of women. Although Joni has been particularly acerbic in her recollections of her relationship with Chuck, there is much more at play here than a bad marriage. The fingerprints of continuing patriarchal society—both within and without that counterculture—are all over Joni's experience of the 1960s, from the imposed shame for an unplanned pregnancy, the muted pain of the foster home, the exploitative marriage right through to the loneliness of life as a solo female musician. It is the crystallization, to quote Coviello once more, of her “habitual resistance to ‘freedom’ itself, in the offered registers.”Footnote 87 It is hard to believe that Joni was only 23 years old in October 1967.

Embracing care as a guiding impulse not only foregrounds the challenging and often cruel cultural landscape that Joni ventured into in her early years as a budding professional musician; it also helps us to make sense of how such experiences became enfolded, stylistically and interpretatively, into her musical practice. It does not replace critique: Criticality and persona theory remain vital tools for studying popular musicians, or any musicians for that matter, and Joni's later career furnishes a telling example. Her participation in the racist practice of blackface at parties in 1976 (as the “only black man in the room”) and for her ninth record, Don Juan's Reckless Daughter, must come in for critical scrutiny.Footnote 88 Indeed, Miles Parks Grier has shown how commonly Joni's supporters either sanitize or minimize this episode in her life.Footnote 89 My point is simply that there will always be space for critique but, likewise, that it need not be our default modus operandi. In this article, I have sketched an alternative which strives for an intellectual disposition of care, one which, when appropriate, can cradle the historical groundwork, analytical thinking, and other modes of inquiry which we routinely bring to our scholarly tasks.

The “definitive” studio recording of “Urge for Going” would have to wait until 1971. Originally destined for Blue but ultimately omitted in favor of newer songs, Joni eventually released it as a B-side to “You Turn Me On, I'm a Radio” in 1972, the lead single from her fifth record, For The Roses. There is much about Joni's 1967 “Urge for Going” that is recognizable in this studio recording, but once again, it is her voice that attracts the most attention: The forward placement and smooth, resonant legato of her mixed voice is so far from the youthful breathiness of her earlier performances, and there is a confidence to the metrical ambiguity of the lyrics. But perhaps the gesture that most neatly symbolizes the transformation that has taken place is her addition of blue, flattened thirds in the vocal part at the beginning of each chorus.Footnote 90 Wrapped up in those blue notes—and the blueness of this 1971 recording in general—are years of poetic and musical maturation distilled into a song of experience.

Adam Behan is Assistant Professor of Music at Maynooth University. His research is situated within performance studies, and he works primarily on music in the twentieth century, classical and popular. His work has been published in Twentieth-Century Music, Music Analysis, Quodlibet, and Music & Letters.