Introduction

Future retirement trends have become an increasingly important social and political issue in Britain. The last 15 or more years have seen a variety of policy initiatives aimed at reversing the trend to male ‘early’ retirement and encouraging people to remain in work for longer. The voluntaristic initiatives against age discrimination in employment under the Major and Blair governments have been followed by measures such as the improved incentive to delay claiming the state pension, the implementation of the Employment Equality (Age) Regulations in October 2006 and the decision to raise state pension ages in the future (eventually, in stages, to 68 by 2046).

The ostensible reasons for this are now well known, and have been thoroughly discussed. First, the period since the 1970s has seen a marked acceleration in the decline in the economic activity rates of men aged 50–64, and a small rise in those of women, raising the question of whether supporting a large non-working population in late middle age is fiscally sustainable. Concerns have been mitigated somewhat by the rise in the employment rates of older people that has taken place since 1994. However, if this is but a temporary respite, Britain faces the prospect of slowly falling average ages of male retirement far into the future.

A second reason is that Britain will have an ageing population after the second decade of this century, as the baby boomers move into retirement. On present trends, the proportion of the total UK population aged 65 and over (65+) will rise from 16 per cent in 2005 to 22 per cent in 2031. By 2022 there will be 3,000,000 more working-age people over the age of 50, and 1,000,000 fewer under the age of 50, making it imperative to raise the employment rates of older people (Whiting, Reference Whiting2005: 287). Of course, the precise age structure of Britain's twenty-first century population remains in the realm of conjecture. Much will depend on future birth rates, death rates at older ages and levels of immigration: the birth rate has recently risen to its highest level since 1980, and unexpectedly high levels of immigration have boosted population numbers to 60,587,000 in mid-2006, with over 70,000,000 projected for 2051 (ONS, 2007a, 2007b). Growth of this magnitude will reduce the gerontic dependency ratio. Nevertheless, a future ageing population will present considerable fiscal challenges.

A third reason is that extending working lives seems to be the least unpalatable method of improving the basic state pension after its long fall in relative value since 1980 – from 20 per cent of male average earnings in the late 1970s, to 15 per cent in the early 1990s (which, had it continued unchecked, would have fallen to 6 per cent by the year 2040) (Johnson, Reference Johnson1994). Occupational and private pensions are in crisis, with four out of five final salary schemes now closed to new entrants (Association of Consulting Actuaries, 2007); money-purchase schemes have diminished in value; and the incomes yielded by the whole private pension sector remain poor. For example, in 2005/06 the average income from private or occupational pensions received by the wealthiest quintile of retired households was only £17,730 per annum, and this would have been very unequally distributed within that quintile; the poorest quintile of households received an average of £1,230 per annum; and the average for all households was only £6,230 per annum (Jones, Reference Jones2007: 18).

Finally, there has been some concern that early retirement is robbing the British economy of skilled employees and human capital, thereby inhibiting economic growth. Various speculative estimates have been made of the extent of this loss – £31 billion in 2002, according to the Employers Forum on Age (Employers Forum on Age, 2002). Early retirement has also created a human tragedy of deindustrialised older men who have been stripped of their work-based identities (Macnicol, Reference Macnicol2006: 12, 90–2).

Matters of interpretation

On the face of it, therefore, there would appear to be an urgent need to extend working lives. However, the empirical underpinnings behind this urgency require further exploration, since they are open to varying interpretations. A rather more critical scrutiny is therefore required.

First, the trend to male ‘early’ retirement must be examined. This is often presented as a recent (post-1970s) phenomenon. However, it is actually a long-run trend and therefore cannot be reversed by withdrawing benefits. The economic activity rates of men aged 60–4 fell slightly in the 1920s and more rapidly in the recession and economic restructuring of the 1930s. (Since there was no census in 1941, this conclusion can be reached only by the use of contemporary testimonial and social survey evidence.) The significance of this has been obscured by the buoyancy of older men's employment in the 1950s and 1960s, when manufacturing enjoyed a period of temporary prosperity. Hence the economic activity rates of men aged 60–4 were 88.7 per cent in 1921 and 87.2 per cent in 1931, rising slightly to 87.7 per cent in 1951 and more sharply to 91.0 per cent in 1961. The extent to which the post-war blue-collar economy protected the labour market niche occupied by older men is demonstrated by the fact that the economic activity rates of men aged 65+ fell by only one percentage point in the 1960s, from 24.4 per cent in 1961 to 23.5 per cent in 1971 – by far their slowest fall in any decade between 1881 and 2001. It was therefore with some relief that the 1954 Phillips Committee Report noted that the pre-war trend to earlier retirement appeared to have been ‘arrested and perhaps even reversed’ (Committee on the Economic and Financial Problems of the Provision for Old Age, 1954: 24). Raising state pension ages had been under discussion in the early 1950s. Hugh Gaitskell, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, had warned in 1951 of the increasing proportion of old people and worsening dependency ratios, concluding that ‘we need a totally new outlook on the question of retirement’. Low unemployment, a higher age of entry into employment and rising life expectancy meant that ‘we should work longer and retire later . . . In due course some formal alteration of pension age in pension schemes, both national and occupational, may well be necessary’ (Gaitskell, Reference Gaitskell1951). However, such concerns were allayed by subsequent economic growth – until the OPEC-led oil price shock of 1973 precipitated a ‘second industrial revolution’ that led to the shedding of older workers.

Second, the tendency in recent policy discourses has been to view as misguided short-termism the reliance on male ‘early’ retirement in the 1970s and 1980s as a means of coping with economic restructuring, workforce downsizing and global competition. However, the use of age proxies at that time was entirely rational and widely supported by governments, trade unions and employers. It was one of several swings in official policies towards older workers that have occurred over the past 80 years between the polar opposites of retention and early exit (both being undertaken in the name of economic efficiency) (Macnicol, Reference Macnicol2006: 35). Just as unemployment was used as a deflationary device in the 1980s and early 1990s (and was therefore seen in 1991 by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Norman Lamont, as a price ‘well worth paying’ to reduce inflation (Lamont, Reference Lamont1999: 90)), so early retirement was a widely supported means of facilitating economic modernisation.

A third factor to consider is the recent rise in older people's employment rates. For those aged between 50 and state pension age, these have risen from 62.4 per cent in the spring of 1994 to 71.7 per cent in the second quarter of 2007. Interestingly, their economic activity rates have risen less rapidly, and the number of people aged 50 to state pension age who are economically inactive has increased (because of a growth in total numbers), from 5,547,000 in the fourth quarter of 1999 to 6,445,000 in the second quarter of 2007 (Whiting, Reference Whiting2005: 287; DWP, 2007a: 7). Even more striking has been the increase in employment among people above state pension age, such that now 1,308,000 are working (attracting comment in the press, some of it interestingly critical (Cecil, Reference Cecil2006)). Part of this may be through choice, and therefore to be welcomed. On the other hand, part has been driven by urgent necessity, caused by falling stock market values, the erosion of private pensions, the collapse of many occupational pension schemes, increasing consumer debt and the impossibility of saving.

The vital question is whether the economic foundations for these recent rises are firm and long term, or precarious and short term. If the former is the case – the result of a ‘sound’ economic strategy and ‘successful labour market policies’ promoting deregulation, flexibility, wage elasticity and labour mobility (DWP, 2006: 14–16) – then the buoyant economic conditions can be maintained. However, there is an opposing view, based on less favourable underlying trends. Sceptics point out that the long economic boom pre-dated 1997 – its commencement coincided with, and was perhaps triggered by, Britain's exit from the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992 – and that therefore New Labour can take little credit for it (apart from perhaps sustaining it): growth has been driven by global economic forces and must soon come to an end. The recent troubles of the Northern Rock Building Society in the UK and the whole sub-prime lending market in the USA might be vindications of the view that the UK's apparent economic prosperity is built upon a quicksand foundation – unsustainable levels of borrowing, inflated house prices, an overvalued stock market, a dangerously small manufacturing base, undue reliance on financial services, continued destruction of the environment, and so on – all amounting to what two financial journalists have called ‘one big offshore hedge fund’ with ‘growth artificially induced by debt’ (Elliot and Atkinson, Reference Elliot and Atkinson2007: 74, 30).

The likely future gains in life expectancy at age 65 are also the subject of some controversy. We cannot necessarily assume that disability-free life expectancy will increase in the future as rapidly as will life expectancy, and that health and working capacity will simultaneously improve. For a large minority of the population, health status may decline because of negative factors such as obesity, sedentary lifestyles, resistance to antibiotics, new epidemics, widening income inequality and so on. On present trends, more than half of adults and a quarter of children will be clinically obese by 2050 – a doubling of 2004 levels – giving rise to warnings that obesity could be a crisis potentially as serious as climate change (Mulholland, Reference Mulholland2007). Likewise, alarm has been expressed over future levels of hypertension, caused by binge drinking, smoking, a salt-rich diet and lack of exercise (Messerli et al., Reference Messerli, Williams and Ritz2007). The incidence of these negative trends will be exacerbated by larger numbers moving into old age: for example, only recently the National Audit Office has warned that cases of dementia may rise from an estimated 560,000 at present to 750,000 by 2020 and 1,400,000 by 2051 (National Audit Office, 2007). Such negative factors may principally affect the oldest-old who are well above working age, but they may pull average health status down and shorten life expectancy at age 65 for a substantial minority.

The hazards of demographic forecasting can be illustrated by the ongoing debate over life expectancy projections. In recent years, there has been much inaccurate comment in the press to the effect that ‘people are living longer’ – comment, which, on closer inspection, turns out to be empirically contentious. One example will suffice. In September 2005, the Continuous Mortality Investigation (CMI) published data which were reported in the press as showing that ‘we are all [sic] living longer’. The new CMI mortality tables indicated that a man aged 65 in 2005 could expect to live to 86 years and 7 months – a remarkable three-and-a-half years longer than in 1997 – and the projection for 2015 was 89 years and 10 months. These data, it was said, were ‘likely to fuel calls for the retirement age to be increased’ (Jones, Reference Jones2005). Another headline categorically stated that the ‘ageing process may mean working longer’ (Knight, Reference Knight2005). However, the CMI sample was based on people who had bought life insurance and pension plans, and was therefore biased towards the higher social classes (who enjoy an eight-year advantage in life expectancy at birth compared with manual workers, and a five-year one at age 65). And the study repeatedly emphasised that there was considerable uncertainty in all estimates of future mortality, given the possible negative health trends in the future. These widely reported projections were much higher than those released by the Office for National Statistics one year later, which suggested that average life expectancy at age 65 in the United Kingdom had increased between 1980–2 and 2003–5 by 3.7 years for males (to 16.6 years) and by 2.5 years for females (to 19.4 years) (ONS, 2006a).

For the Pensions Commission and the 2006 Green Paper, gains in life expectancy at age 65 have been ‘dramatic’, recent and unexpected. Compounding this problem is said to be the ‘fool's paradise’ and ‘irrational exuberance’ of high stock market values in the 1990s that deluded myopic pension fund managers and discouraged them from effecting the cutbacks in defined benefit schemes that were a fiscal urgency (Pensions Commission, 2004: 2, 94, 123; DWP, 2006: 63). It is an explanatory narrative that has proved quite durable. For example, in a perceptive account of older workers’ problems, Patrick Grattan argues that ‘With the benefit of hindsight we were all (including the actuarial profession), sleep walking for a few decades. The Pensions Commission administered a reality check in its first report in October 2004’ (Grattan, Reference Grattan, Bauld, Clarke and Maltby2006: 296).

In fact, life expectancy at age 65 for women began to improve noticeably in the 1950s, and for men in the 1960s, after stagnating for much of the twentieth century. More rapid increases occurred from the 1970s. The causes are complex, but it is likely that blue-collar industrial jobs caused men to be ‘worn out’ by late middle age and die relatively quickly after retirement; the shift to a service-based economy appears to have been beneficial in this respect (as also may have been the trend to earlier retirement). Again, the implication that actuaries have been ‘sleep walking’ to disaster is unwarranted. One reason why the ‘compression of morbidity’ debate on health status and old age took off in the 1970s was precisely because demographers noticed that life expectancy at age 65 was improving, yet health care utilisation rates and levels of recorded morbidity were simultaneously increasing, raising the prospect of growing numbers of health-impaired older people (Verbrugge, Reference Verbrugge1984). Admittedly, as recently as the 1980s British mortality projections underestimated the extent of the decline; but it is clear that the overall problem has been attracting comment for some three decades.

Older workers and the New Deals

It is important to remember that the strategy of extending working lives is inextricably linked to welfare reform, the New Deals and the replacement of a ‘passive’ welfare state with an ‘active’ one. The publication of the 2006 Green Paper, A New Deal for Welfare: Empowering People to Work, and the March 2007 Freud report marked a new and potentially more aggressive phase of welfare reform, in which the analytical distinction between ‘human capital’ and ‘work-first’ approaches is becoming increasingly blurred. The aim is to get 1,000,000 more older people back into paid employment, as a contribution towards the target of an overall employment rate of 80 per cent among the population of working age. Interestingly, the Freud report argues that the old full employment fiscal policies of the 1960s have gradually been replaced by labour market activation through the New Deals. In other words, the welfare state is increasingly becoming an instrument of employment policy (Freud, Reference Freud2007: 12).

The public justifications for the New Deals are several. The most beguiling is that many sections of the population appeared to have been ‘written off’ in the years of Conservative governments up to 1997 (one third of people aged between 50 and state pension age jobless, the numbers on unemployment benefits having increased by 50 per cent since 1979, a tripling of claims to incapacity benefits since the 1970s, nearly one third of Britain's children in relative poverty) (DWP, 2006: 14). Labour market participation is said to confer identity, dignity, improved health, higher incomes and greater self-worth on citizens, enhancing their social capital. (Much, of course, depends on the quality and remuneration of the jobs.) Accordingly, the proposed tightening up of work obligation, with the implied threat of coercion, is attractively presented as ‘empowerment’ – most strikingly in the use of the ‘social’ model of disability to justify more work obligation for disabled people (Daguerre, Reference Daguerre2007: 76).

Workfare can be seen as politically astute, neutralising the undoubtedly strong public hostility towards benefit ‘scroungers’, although more proactive New Deals are likely to encourage the public to see more claimants as ‘workshy’. There are also rather more controversial justifications for workfare – such as the fact that making as many citizens as possible support themselves through paid employment minimises redistribution through social security (the largest single item in public expenditure). While this is currently being presented as a fiscal necessity if pensions are to be improved (DWP, 2006: 20, 63), it has simultaneously enabled New Labour to present a populist, low-tax agenda to the electorate. The New Deals are also part of a broader supply-side approach to economic and social problems which focuses on the behaviour of individuals and the ‘barriers’ that prevent them working, thereby individualising unemployment and diverting attention from demand-side factors (including the behaviour of multinational firms and international flows of capital).

There are two further impulses behind workfare which are even more contentious. First, it is essentially a rationalisation of existing labour market trends. In the short term, the employment rates of many population sub-groups have been rising since the early 1990s, as a consequence of a long period of economic stability and growth. Had this not been the case, the New Deals would not have been politically viable. Of course, not all groups have experienced this rise: youth joblessness remains high, and claims to incapacity benefits have fallen only recently (and by relatively little). There is also continuing concern about the 1,700,000 ‘hidden unemployed’ (those on incapacity benefits but desiring to work, plus the unemployed not claiming benefits) which, if added to the ‘claimant count’ unemployed, gives a total of nearly 2,600,000 de facto unemployed (Beatty et al., Reference Beatty, Fothergill, Gore and Powell2007: 22). Again, the aggregate number of working-age people who are economically inactive now stands at 7,890,000. An expanding labour force is accompanied by persistently high levels of economic inactivity, raising the disturbing question of whether there are enough suitable jobs for all those who want them. This is in sharp contrast to the official view that Britain is now close to a full-employment economy (Hain, Reference Hain2007). Nevertheless, it is obvious to all that a major reason for the apparent success of the New Deals is that they have coincided with a 15-year economic boom.

In the long term, the New Deals are also a product of the slow growth of part-time jobs. Since 1951, part-time jobs in the British economy have increased from 831,000 to 7,560,000 (ONS, 2006b, 2008). This alone makes official claims about the overall employment rate having reached 74.8 per cent somewhat dubious, and renders the target 80 per cent employment rate among the working age population attainable. Giving each part-time job a notional 50 per cent full-time value would deflate today's employment rate to about 64 per cent. Much net job growth in the British economy is in part-time and low-paid work. The New Deals can therefore be seen as the policy response to these long-run labour market changes: increasingly, it is argued that every individual citizen without caring responsibilities should support himself or herself via paid employment – as in the New Deal for Partners (DWP, 2006: 70). The male breadwinner family wage is being replaced by the individualisation of economic activity.

Finally, it is important to remember that, ultimately, welfare reform is integral to New Labour's overall macro-economic strategy of enhancing global competitiveness and achieving stable, non-inflationary economic growth by expanding labour supply, thereby driving down wages, lowering production costs and keeping interest rates low. It is an approach most famously articulated in the supply-side theories of Richard Layard, and has been dominant within the Treasury since the late 1990s (Daguerre, Reference Daguerre2007: 69). This is occasionally mentioned in official publications. Sometimes the language is euphemistic, as when the 2006 Green Paper praises the government's ‘conscious effort to build macroeconomic stability, combined with a new approach to welfare’ and warns that Britain's strength as a global economic player means being able to rival the emerging economic superpowers of China and India (DWP, 2006: 15, 19, 20), or when the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions warns that welfare reform is needed ‘at a time when the global forces of economic and demographic change present new and even greater challenges for our economy and labour market’ (Hain, Reference Hain2007). At other times it is explicit, as when Winning the Generation Game states that ‘Increasing the number of people effectively competing for jobs actually increases the number of jobs in the economy . . . in a flexible labour market, wages can and do adjust. More people competing for jobs means that people are less keen to demand wage increases’ (Cabinet Office, 2000: 39).

New Labour therefore stands in the long tradition of classical economists who have always seen wage reductions as a necessary prerequisite for non-inflationary economic growth: by lowering production costs, they reduce the price of goods and services, making them cheaper on world markets; and the wage-bargaining power of organised labour is undermined if more workers compete for jobs. This strategy has a long history. For example, wage-reduction arguments were advanced during the economic restructuring of the 1930s depression. Anti-Keynesians such as Lionel Robbins were frustrated that unemployment benefit and assistance levels rendered wages relatively inelastic: as Robbins put it, the ‘rigidity of wages’ in Britain following the First World War was ‘a by-product of unemployment insurance’ (Robbins, Reference Robbins1934: 61). Likewise, Patrick Minford's proposed cure for unemployment in the 1980s included cuts in welfare benefits and compulsory workfare (Minford, Reference Minford1983: 48–9). Such arguments are again being advanced in today's globalised world.

Future employment patterns

New Labour's perspective on the problems of older workers is an almost exclusively supply-side one, based on behavioural economics. Labour market demand is little mentioned. ‘The problem is not a lack of jobs’, declares the 2006 Green Paper (DWP, 2006: 18), ignoring the complex mismatches of age, skill, region, gender, sector and so on, that characterise modern economies and have reduced employment opportunities for older men. The solution is one-dimensionally located at the level of the individual firm, via an attack on the irrational ‘discriminatory’ policies and ‘outdated prejudices’ of employers (DWP, 2006: 65–6). Emphasis is placed on achieving ‘cultural change’ on the part of employers and employees by addressing the ‘personal factors’ that allegedly prevent economically inactive people from working, and by ‘incentivising’ work. When retirement is discussed, it is in the context of ‘the decision to retire’ (implying voluntary choice).

However, supply-side optimism cannot obscure some very real underlying structural problems. Basically, it is not clear whether working later in life is to be achieved via an expansion of existing patterns of employment, or via radically new ones. If it is to be the former, then several problems exist. The main difficulty faced by older workers who are made unemployed is regaining good employment, and therefore the solution is seen, logically, as ensuring their retention in an existing job. However, retention will threaten the employment prospects of young job seekers unless supply-side policies can cause individual firms with high proportions of older workers to expand enough to retain 1,000,000 additional employees. The scope for such expansion is very doubtful. Again, there are many legitimate obstacles to longer working, such as a greater intensification of work, leading to more employee burn-out, or the fact that 24 per cent of people aged 45 to 64 are caring for a sick, elderly or disabled person (Evandrou and Glaser, Reference Evandrou and Glaser2003: 583). An unresolved contradiction is that expanding labour supply can only hold down wages if there is a ‘lump of labour’ (a fixed volume of employment); if, as New Labour argues, there is not a ‘lump of labour’, more labour supply will lead to more jobs being created, with the bargaining power of workers remaining strong. To be sure, more people working is associated with an expanding economy (DWP, 2006: 66); but it is likely that economic growth is the cause of employment growth, rather than the other way round. An economy cannot grow without a supply of labour; but labour supply does not of itself guarantee economic growth.

The second problem is the regional variation in older people's employment rates. For people aged between 50 and state pension age, these vary from 77.8 per cent in the South East to 64.9 per cent in Inner London, 65.1 per cent in Wales and 65.7 per cent in the North East. The variation in the proportions inactive due to sickness, disability or injury is even greater: 56.7 per cent in Wales and in the North East and 35.5 per cent in the South East (DWP, 2007a: 13). If working lives are to be extended, they must be extended in the deindustrialised, economically depressed parts of Britain.

A third difficulty is that part-time working and self-employment become more prevalent as cohorts age. Hence the proportions of people aged between 50 and state pension age working part-time are currently 12.0 per cent (men) and 43.0 per cent (women), rising to 66.3 per cent (men) and 70.9 per cent (women) for those above state pension age. Self-employment likewise rises proportionately, from 22.9 per cent (men) and 10.2 per cent (women) for those aged 50 to state pension age to 43.4 per cent (men) and 15.5 per cent (women) above state pension age (DWP, 2007a: 10). It is difficult to envisage how extensions of part-time work will produce the levels of income necessary to sustain people working to age 68 (particularly as five-sixths of part-time jobs are currently performed by women), or precisely what policies will encourage self-employment. The 2006 Green Paper articulates the laudable aim of working with employers to extend ‘flexible’ working opportunities, but it is not very explicit on precisely how this might be done (DWP, 2006: 62). The first report of the Turner Commission was likewise rather reticent on specific policy solutions, listing five general reasons why older people's employment rates ‘could’ rise in the future: continuation of ‘sound macroeconomic policy’; the increasing shift from defined benefit to defined contribution pension provision; continued focus on Incapacity Benefit reform; active labour market policies to encourage search for work at all ages; and age discrimination legislation (Pensions Commission, 2004: 38). The second, third and fourth imply coercion. The fifth articulates the legitimating principle justifying this coercion. Only the first outlines an economic strategy, and is a mere five words in a report of over 300 pages. In its second report, the Turner Commission was only a little more forthcoming, still limiting itself to a discussion of the incentives implicit in state taxation, benefit and pension systems and the need to ‘send a powerful signal’ via the removal of the default retirement age. Once again, it was an exclusively supply-side, behavioural analysis, confined to the level of the individual firm (Pensions Commission, 2005: 334–44).

Existing patterns of older people's employment therefore provide a rather fragile basis on which to extend working lives. If, on the other hand, radically new working patterns are to be the basis, then these need to be clearly spelled out. A further problem is that jobless people aged 50+ are very heterogeneous, in terms of their skills, remuneration expectations, work histories, local labour market offerings and so on. This is a problem with all workfare programmes – a ‘one size fits all’ approach is too blunt an instrument to deal with the multiplicity of needs and circumstances (Dean, Reference Dean2003) – but it is particularly difficult with economically inactive older people and recipients of incapacity benefits (categories which often overlap). Providing them with tailor-made career advice and placing them in jobs is thus very challenging (Grattan, Reference Grattan, Bauld, Clarke and Maltby2006: 302–5). Finally, there is the political problem of expecting some citizens to work later in life (especially those worn out by hard manual jobs), while a privileged minority retire early on adequate occupational pensions and then survive longer in retirement.

What does the history of retirement tell us?

Retirement is variegated by many factors – socioeconomic status, prior work history, gender, ethnicity, age, marital status, health status, personality, community networks and so on. The causal impulses can be multi-layered and complex: structural factors merge imperceptibly into circumstantial ones, with ‘choice’ diminishing as one moves down the occupational structure. For example, wealthier married retirees may be more affected by the retirement decision of a spouse; by contrast, blue-collar retirees possess so little choice that such an event will be an irrelevance. There are many other intriguing aspects, such as Henry Aaron's point that retirement generally occurs only once in a lifetime: there can therefore be no trial-and-error experimentation to get it right (Aaron, Reference Aaron and Aaron1999: 67).

Accordingly, researching retirement is methodologically challenging: as two American scholars have remarked, it ‘strains the capacities of economic theory and statistical technique’ (Aaron and Burtless, Reference Aaron, Burtless, Aaron and Burtless1984: 22). The ideal approach would be a three-stage project. The first stage would draw conclusions from observations of labour market, economic, social and cultural change. (Most historical studies have had to be confined to this very broad and general approach.) A second stage would be to conduct interview-based and/or ethnographic research in order to ascertain the motives and circumstances of individual retirees. Much good work of this type has been done (for example, Disney et al., Reference Disney, Grundy and Johnson1997; Arthur, Reference Arthur2003), but there are hazards: such surveys tend to focus over-narrowly on the personal circumstances of respondents, and responses can be affected by factors such as the length of time spent in retirement or the tendency of human beings to rationalise the inevitable. A third stage, therefore, would be to combine the above two approaches: an examination of macro-level changes in the economy and micro-level changes within an individual firm (such as technological innovation, or changes in working practices) would provide the context in which interview-based results would be placed and their veracity tested. Only then could we answer such difficult questions as how to distinguish between ‘voluntary’ and ‘involuntary’ retirement.

Nevertheless, within this complexity two broadly contrasting historical models have been suggested, either in opposition or in some combination (Macnicol, Reference Macnicol and Mokyr2003). Supply-side explanations tend to view the ‘invention of retirement’ as a collective choice, or as a response to specific incentives (notably, accumulated savings, state pensions and private or occupational pensions), with the result that an ‘expectation of retirement’ has become culturally embedded. Such explanations have become more popular in the last 35 years. This may be because increasing pensioner prosperity has indeed enhanced choice and democratised ‘the retirement decision’. However, it is more likely due to a shift in the economic and political climate, resulting in the ascendancy of supply-side, behavioural economics. By contrast, demand-side explanations tend to view the principal causal factor as the slow contraction of the labour market niche that has employed older workers. Beginning in the 1880s, it would be argued, older workers have been deskilled and deindustrialised; this process has accelerated and spread faster down the age structure with the enormous labour market changes that have taken place since the 1970s.

These historical models are of relevance when we consider the employment prospects of older men in the future. The specific incentives to retirement generally cited in supply-side explanations do not stand up to critical scrutiny when seeking an aggregate explanation: they only apply to a wealthy minority of retirees. Throughout history, the state pension has had little effect: for example, in the early 1950s two thirds of men worked on past state pension age, whereas now two thirds of men have left work before that age. It follows therefore that raising the state pension age will not by itself extend working lives. As demonstrated earlier, private and occupational pensions have been too low to act as an inducement for any other than a small minority of high earners – and they tend to retire latest. Employers’ early exit incentives have had some effect, but these were only ever introduced out of economic necessity, to assist workforce downsizing and firm restructuring (Vickerstaff et al., Reference Vickerstaff, Baldock, Cox and Keen2004). Accumulated savings at a level that would encourage retirement are held by only the very wealthiest. Recent estimates of the proportion who are saving adequately for retirement vary between, at best, one half and, at worst, one tenth (Howard, Reference Howard2007; Wachman, Reference Wachman2007). This is reflected in the incomes from investments obtained by pensioner households: for the poorest 60 per cent of such households, it averages less than £500 per annum per household; for the second-richest quintile it averages £980 per household; and for the richest quintile, it averages £5,410 per household (Jones, Reference Jones2007: 18). Indeed, the Turner Commission was set up partly because of low levels of saving for old age: it calculates that c.9,600,000 people are not saving enough (Pensions Commission, 2004: 159). The 2006 Green Paper admits that citizens have been making poor and badly informed choices regarding their own early retirements (for example, on matters such as life expectancy and the required level of savings); ironically, it simultaneously argues that providing citizens with more retirement choice is a central government aim (DWP, 2006: 66–7). Rational choice explanations also do not fit easily with the evidence that only about one third of jobless men aged 50–64 (7.9 per cent of the total age group) define themselves as ‘retired’ (DWP, 2007a: 8). Finally, it is undoubtedly the case that an expectation of retirement has become culturally embedded (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson2002: 12–13), but this is essentially a rationalisation and acceptance of long-run economic trends.

Demand-side explanations, while being rather broad-brush and general, nevertheless offer a far better explanation for the spread of retirement since the 1880s. They accord with the voluminous testimonial evidence from the late nineteenth century that older workers were finding it increasingly difficult to hold on to their jobs in a new industrial era of more scientific management regimes, with a greater emphasis on individual productivity (Macnicol, Reference Macnicol1998: 18–59); they explain the correlation between the spread of retirement and prevailing economic conditions (including the recession of the 1930s, the re-enlistment of many older workers in the buoyant economy of World War II, and the spread of male ‘early’ retirement with the decline of manufacturing in the 1970s and 1980s); and they fit with the evidence that the majority of recent ‘early’ retirements have been involuntary – reluctantly acknowledged in official circles (Cabinet Office, 2000: 22), even if this has not materially affected policy responses – and that those who retire earliest tend to be the lowest paid, least skilled, most unhealthy and least able to exercise choice (Whiting, Reference Whiting2005: 287–8). If demand-side explanations are more convincing in the long run, therefore, extending working lives can only be achieved if more jobs suitable for older workers are created. Supply-side policies will only have a limited effect.

Exploring the future

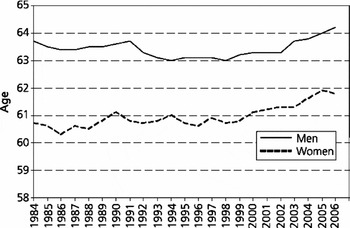

So much for the past: what about the future? Interestingly, from an examination of the history of retirement, two very different conclusions could be drawn. On the one hand, the fact that male retirement originated in the 1880s and has slowly spread down the age structure means that it is a long-run trend that is unlikely to be reversed. From this perspective, the present upward movement in older people's employment rates is but a temporary aberration, and will not be sustained. A world recession – triggered, say, by political turbulence in the Middle East and a concomitant sharp rise in the price of oil, or by economic disruptions caused by political terrorism within particular nation states, or by the sheer unsustainability of consumer debt – might suddenly and dramatically reverse it. British people now owe £1.34 trillion in mortgage and unsecured debt – slightly higher than the UK's total projected Gross Domestic Product for 2007 (Grant Thornton News, 2007). A debt-driven recession and a rise in interest rates would cause consumers to reduce their spending on retail goods, and lead to redundancies in precisely those sectors in which older workers have recently gained employment. We may find ourselves back in the pessimism of the early 1990s, when it seemed that the trend to male ‘early’ retirement was irreversible, and would inexorably continue (Laczko and Phillipson, Reference Laczko and Phillipson1991). Much depends on how far the rising employment rates have been caused by New Labour's sound economic management, or by world economic forces over which individual governments have relatively little control. What we do know is that older men's employment rates are very sensitive to overall economic conditions. Hence the employment rates of men aged 55–9 fell from the mid 1970s to the mid 1980s, then rose in the late 1980s with a tightening labour market and a brief economic boom, and then fell again in the recession between 1990 and 1994, only to rise again slowly (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson2002: 5; Pensions Commission, 2004: 36–7). Put another way, the average age of male labour market exit rose between 1987 and 1991, then fell; only by 2003 was the 1991 level regained (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Average age at labour market exit, 1984–2006, by sex

Reproduced by permission of the Office for National Statistics

Source: Freud, Reference Freud2007: 33

On the other hand, we may have entered a completely new phase of economic development, in which the labour of older people will again be needed, much as it was in the nineteenth century – although there may be significant differences (such as an increasing feminisation of work at later ages). Since long-term sickness or disability are, on the face of it, the most frequently cited reasons for early exit, it would follow that better occupational health policies could improve working capacity and employability (say, on the Finnish model of ‘workability’) (Phillipson and Smith, Reference Phillipson and Smith2005: 78–9; Maltby, Reference Maltby, Loretto, Vickerstaff and White2007). However, improving employability does not by itself create jobs. The problem is that health and working capacity at later ages are often self-defined in relation to the availability of jobs: there is plenty of recognition that self-reported health is affected by higher expectations, but much less acknowledgement of the labour market effects (Beatty and Fothergill, Reference Beatty, Fothergill, Loretto, Vickerstaff and White2007). To be sure, cultural and attitudinal barriers to men taking the new hypercasualised, postindustrial jobs may be breaking down. Deindustrialised parts of Britain are slowly reviving – even Merthyr Tydfil, arguably the epitome of deindustrialisation (Seager, Reference Seager2007). Again, workfare may become so draconian in the future that older, economically inactive people have little choice.

The key issue will be the quality and remuneration of such new, post-industrial jobs. Many of them are likely to be low skilled and poorly paid: call centre work, shelf stacking, food processing and so on. Is the ‘McDonaldisation of old age’ really desirable? Where the balance of rights and responsibilities is concerned, should the former include really ‘making work pay’ by highly redistributive in-work benefits or raised income tax allowances for older workers (with claw-back applied to higher earners), instead of compulsory workfare enforced by the threat of benefit withdrawal? This is an issue on which New Labour has been somewhat reticent, not least because of the class double standards involved. The ideal of allowing citizens to choose when they wish to retire is superficially attractive, but does not sit easily with the evidence that the majority of recent ‘early’ retirements have not been through choice. A problematic scenario would be a return to the nineteenth century working-class experience of ‘life cycle de-skilling’ (Ransome and Sutch, Reference Ransome, Sutch, Kertzer and Laslett1995: 303–27), in which less skilled workers moved to progressively lighter and more menial jobs as they aged, their diminishing incomes often being supplemented by Poor Law outdoor relief. If so, it will be interesting to see whether twenty-first century tax and benefit policies will be as generous in this respect as was the nineteenth century Poor Law.

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at a special session on ‘The Future for Older Workers’ at the Social Policy Association Annual Conference on 24 July 2007. I should like to thank all who participated in the session, especially my fellow presenters (Tony Maltby, Chris Phillipson and Sarah Vickerstaff). Useful comments were also provided by Dr Anne Daguerre and the two anonymous referees.