Introduction

The 3rd c. CE has been the focus of intense scholarly attention and debate in recent decades as the “critical century” for the Roman Empire. Most scholars identify political instability and an institutional crisis triggered by Gothic invasions on the Danube and the Black Sea, by the Sassanian threat in the east, and by a lack of consensus on imperial succession as central to this crisis.Footnote 1 An epidemic mentioned in our sources, the so-called Cyprianic Plague, has occasionally been acknowledged as an additional challenge, but never as a genuine trigger for substantial transformations. Most recently, Kyle Harper in a series of articles and in his 2017 monograph, The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire, has offered a controversial reinterpretation of the evidence connecting a perceived acute crisis during the third quarter of the 3rd c. CE with the “Plague of Cyprian,” which had hitherto basically gone unnoticed in scholarship on ancient pandemics or the 3rd-c. crisis of the Empire.Footnote 2 Harper argues for a series of key tests of resilience during the course of Roman rule: the end of the Roman Climate Optimum sometime around the 2nd c. CE, the Antonine Plague of the late 2nd c. CE, the Cyprianic Plague during the middle of the 3rd c. CE, the Justinianic Plague in the middle of the 6th c. CE, and eventually the Late Antique Little Ice Age in the 6th and 7th c. CE.Footnote 3 According to Harper, these events functioned as stressors stretching the basic structures of the Empire. His hypothesis fits in well with present-day debates on global warming, overpopulation, and the spread of pandemics new and old, and also partly explains the success of his book among a more general public.Footnote 4 Harper argues that this 3rd-c. pestilence entered the Roman Empire from Ethiopia via Egypt in winter 248/9 CE and made its way westward from there, prompting the edict issued by Decius in late 249 CE commanding sacrifices to the imperial gods and Empire-wide persecutions of Christians in 250/1 CE.Footnote 5

My article is a response to Harper's very useful series of articles on this epidemic which constitute its first comprehensive treatment and filled a real lacuna in our knowledge about ancient epidemics. Surprisingly, very few scholars have engaged with this epidemic before Harper and − perhaps even more surprisingly − very few have responded to his conclusions. Based on a careful rereading of the main sources, I offer a critical response to Harper's arguments and challenge his main interpretations about the date of the epidemic, its origins, and the timeline of its spread around the Mediterranean.

The date and alleged origin of the Plague of Cyprian in Egypt

In the following I will reanalyze the substantial literary evidence of this undoubtedly important disease outbreak assembled and presented in full for the first time by Harper.Footnote 6 I present my analysis of the events in chronological order, following the spread of the epidemic around the Mediterranean. Harper's argument for the origin and first appearance of this disease hinges mainly on two letters by Bishop Dionysius of Alexandria quoted in Eusebius's Church History, the letter to Bishop Hierax (Euseb. Hist. eccl. 7.21.1–10) and the letter to the brothers in Egypt (Euseb. Hist. eccl. 7.22.1–11). Based on these two letters, Harper claims that it “seems incontestable that a pandemic disease event erupted by Easter of 249 in Egypt and quickly spread across the empire, reaching Rome by the second half of 251 at the latest and recurring for the next two decades.”Footnote 7 At another juncture, he places the arrival of the disease in Rome even earlier, in the first half of 251 CE:

The letter to Hierax actually places the outbreak of our plague in Alexandria two years before its apparent arrival in Rome and Carthage, allowing us to date its beginnings to 249. This dating is not only plausible, but adds credibility to the narrative of a plague moving from East to West and arriving in Rome in early 251.Footnote 8

Harper considers Dionysius's two letters as the earliest evidence for the Plague of Cyprian, vindicating his theory of an Ethiopian origin of the outbreak.

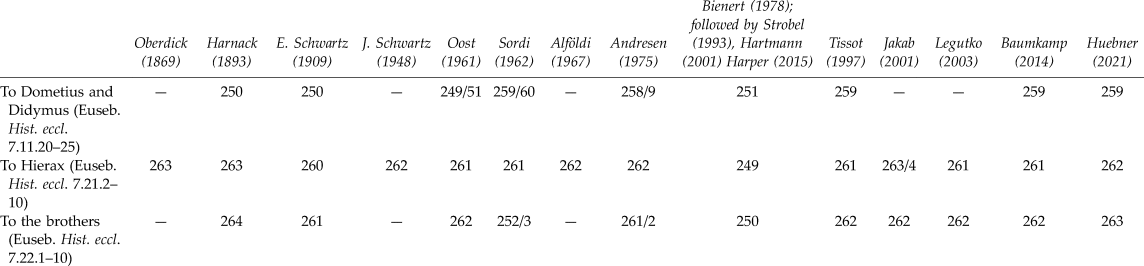

The dating of Dionysius's letters to Hierax and to the brothers in Egypt is, however, far less certain than Harper makes it look and has engendered a vast body of scholarship. In dating the two letters in question to the reign of Decius, Harper follows Strobel and glosses over an entire scholarly discussion (Table 1).Footnote 9 Multiple scholars before and after Strobel are actually in agreement that the two letters must have been written considerably later, and place them almost unanimously in the early 260s CE, a dating that entirely undermines Harper's chronology of how the epidemic unfolded. The sequence of the letters defended by most scholars also respects the order in which they are presented by Eusebius, who is believed to have had a dossier with Dionysius's letters at his disposal and who generally remained true to the chronology of events in his annalistic history.Footnote 10

Table 1. Dating of relevant letters in Eusebius's Church History

Ironically, Harper relies on Strobel's dating of these letters, while Strobel did not believe that Dionysius was referring to an actual plague outbreak at all, seeing here rather “a rhetorical, highly suggestive construct; it belongs to the rhetorical exaggerations.”Footnote 11 While Harper accepts Strobel's dating, he does not follow his interpretation. The first possible reference to the pestilence in Alexandria occurs in Eusebius's Church History in an Easter letter to the brothers Dometius and Didymus (not mentioned by Harper), which has been most convincingly dated to 259 CE.Footnote 12 From his place of exile in the Libyan desert to which he had been sentenced during the persecutions under Valerian between 257 and 260 CE, Dionysius writes:

The presbyters, Maximus, Dioscorus, Demetrius, and Lucius concealed themselves in the city, and visited the brethren secretly; for Faustinus and Aquila, who are more prominent in the world, are wandering in Egypt. But the deacons, Faustus, Eusebius, and Chæremon, have survived those who died in the pestilence.Footnote 13

I therefore conclude that there is no good evidence for an initial outbreak of the pestilence in 249 CE in Alexandria. According to my reading of the relevant sections in Eusebius's Church History, a major outbreak of the disease seems to have hit the city only almost a decade later in the later 250s CE. In the two further Easter letters discussed above − addressed to “Hierax, an Egyptian bishop,” and to “the brothers in Egypt,” and written according to most scholars during the last few years of his life between 262 and 264 CE – Dionysius then laments Alexandrinian factionalism, continuous or successive pestilences (συνɛχɛῖς λοιμοί) and a tremendous loss of men in Alexandria. In these two letters, in my opinion written with hindsight, Dionysius also defends himself against the accusation that he had fled from the persecutions instead of suffering martyrdom, thereby looking back on the past decade of his ministry. He places events in a clear sequence: he had spent the years 249–51 CE in hiding and the span of time from 257 to 260 CE in exile;Footnote 14 after that, gentiles and Christians alike had suffered from both “war and famine.”Footnote 15

This last point must refer to the suppression of the usurpation in Alexandria by the Macriani brothers, who had risen against the emperor Gallienus in August/September 260 CE. Their usurpation in Alexandria ended in fall 261 CE, as the papyrological evidence corroborates.Footnote 16 The role of Mussius Aemilianus, prefect of Egypt, in this conflict is not yet entirely clear.Footnote 17 The Historia Augusta, whose general trustworthiness has been the subject of ongoing debate,Footnote 18 suggests that this Aemilianus, who had been prefect since 257 CE, and was the one who sent the Alexandrinian bishop Dionysius into exile during the persecution of Valerian,Footnote 19 had supported the Macriani in 260/1 CE.Footnote 20 Alföldi suggests that, after the brothers Macriani were defeated, Mussius Aemilianus probably initiated a revolt, since he had backed the brothers and not Gallienus, building a stronghold in the Fayum.Footnote 21 Aurelius Theodotus was sent to Egypt in fall 261 CE to suppress the rebellion which ended in spring 262 CE.Footnote 22

The letter to Hierax (Euseb. Hist. eccl. 7.21.2 − 10) should thus date to the moment when the conflict had just ended – Easter 262 CE.Footnote 23 Dionysius is looking back on months of civil war – rotting bodies still lying in the streets and drifting in the harbor. He has a presentiment that these unsanitary conditions might lead to another wave of the deadly pestilence that had hit Alexandria several years earlier, during the Valerian persecution:

Such are the vile exhalations wafted from land, sea, rivers, and the harbor mists that it is the discharges from corpses rotting down to their component elements that form the dew. Yet people are puzzled as to the source of the constant epidemics, the serious diseases, and the variety of deaths, or why this immense city is depopulated (Euseb. Hist. eccl. 7.21.8, transl. Maier Reference Maier1999).

Such a lament about the recurrent episodes of the pestilence makes no sense in 249 CE, where Harper places this letter, regarding it as a reference to the first outbreak of this disease. A brief respite then ensued, Dionysius narrates, before another outbreak of the disease irrupted violently in Alexandria.Footnote 24 In his Easter letter to the brothers in Alexandria, written according to most scholars during the final years of his life, Dionysius laments that people were suffering and that many had died. By the time of its writing, around Easter, it seems that the pestilence had begun to ebb. This wave must thus have started in the winter months of 262/3 CE, and Dionysius most likely wrote the letter on Easter 263 CE.Footnote 25 He died in 264 or 265 CE.

The timeline of the plague's spread around the Mediterranean

Let us reexamine the remaining evidence for the Cyprianic Plague, focusing on the reconstruction of the spread of this epidemic. Thanks to Harper's meticulous study we have an excellent overview of the existing sources, most importantly (apart from the letters of Dionysius already discussed): Cyprian and his biographer, Pontius of Carthage, Porphyry, Zosimus, Eutropius, Aurelius Victor, the Historia Augusta, the Chronicle of Eusebius in its Armenian and Latin translation, and later on Zonaras. While Cyprian, Pontius, and Porphyry were eyewitnesses of the epidemic, Zosimus, Aurelius Victor, and the Historia Augusta probably relied on the lost historic works of further contemporaries of the pestilence, the Athenian historians Dexippus and Philostratus, writing from the perspective of the Greek mainland, and the hypothesized Enmannsche Kaisergeschichte, a contemporary historical account in Latin, whose author was presumably based in Rome.Footnote 26

Contrary to Harper's account, the emperor Decius was already dead by the time that we hear about the epidemic for the first time. Among the first victims seems to have been − at least according to Aurelius Victor − Decius's son and successor, 15-year-old Hostilianus, who allegedly died of the disease in summer 251 CE:

When the senators had learned of this they voted the rank of Augustus to Gallus and Hostilianus and appointed Volusianus, the son of Gallus, as Caesar. Thereafter a plague broke out and while it raged ever more violently Hostilianus died but Gallus and Volusianus won popular favor because they meticulously and assiduously arranged the burials of all the poorest folks (Aur. Vict. Caes. 30.1–2, transl. Bird Reference Bird1994).

The Epitome de Caesaribus, presumably based on the lost Enmannsche Kaisergeschichte,Footnote 27 echoes this without adding any further information: “Vibius Gallus, with Volusianus, his son, ruled two years. In their time, Hostilianus Perpenna was made imperator by the senate and, not much later, was consumed by the plague.” (Epit. de Caes. 30.1.2, transl. Banchich Reference Banchich2018). No date is given in any of our sources for the death of Hostilianus, but it must have occurred shortly after the beginning of Trebonianus Gallus's reign. Decius and his elder son, Herennius, perished in early June 251 CE in the battle of Abritus, and Trebonianus Gallus, one of Decius's generals, was made emperor by the troops immediately thereafter.Footnote 28 Hostilianus, the surviving younger son of Decius, was also proclaimed Augustus and adopted by Trebonianus Gallus.Footnote 29 On his own son, Volusianus, Trebonianus Gallus bestowed the title of Caesar.Footnote 30 When Hostilianus died shortly thereafter, Gallus then appointed his son Volusianus as fellow Augustus and moved to Rome in fall 251 CE, where they remained until summer 253 CE.

There is a tradition according to which Hostilianus died of the pestilence in the military headquarters at Viminacium in Moesia Superior. The Archaeological Park of Viminacium boasts that a mausoleum excavated at the site and measuring approximately 20 × 20 m is his burial site.Footnote 31 The mausoleum contained a very rare bustum burial, which means that after the body of the deceased had burned on the funeral pyre, the tomb was built on the spot around the ashes. Moreover, after the burial a thin layer of earth was cast over the remains in the mausoleum, before the cremation site was sealed off by stone and lime plaster. Remains of the bones found in the tomb were recently sent for ancient DNA analysis.Footnote 32 However, no inscription confirming this identification has been found yet.

The possibility that Hostilianus was indeed in Viminacium around the time that his father and brother fell in battle in May/June 251 CE finds some confirmation in the numismatic evidence. An entire series of coins was struck by the mint of Viminacium in the local year 12 (250/1 CE) for Hostilianus as Caesar – undoubtedly on the occasion of the latter's visit to the town.Footnote 33 Furthermore, the mint struck coins for Hostilianus as Augustus which also show the year 12 (250/1 CE), but no doubt belong to the final weeks of this year, i.e., July/August 251 CE.Footnote 34 Peculiarly, for the year 13 (251/2 CE) coins were struck again in the name of Hostilianus as Caesar, and might point to the fact that the first few weeks of Trebonianus Gallus's reign were rather tumultuous, at least as long as Hostilianus was still alive.Footnote 35 All this evidence suggests that the younger son of Decius did not remain in Rome but came to the region during the last year of his family's rule.Footnote 36 Was he made emperor by the troops only to die during the first outbreak of the epidemic, weeks later, in the military headquarters?

Zosimus, a pagan historian writing at the turn of the 6th c. CE in Constantinople, is our most detailed source for the age of the 3rd-c. emperors. He does not mention the pestilence at all in connection with the young emperor's death, and, following a different tradition, reports that Hostilianus was murdered by his colleague, the emperor Trebonianus Gallus – an episode that apparently took place in Rome:

After this settlement, Gallus went to Rome very proud of the peace he had made with the barbarians. And although at first he referred kindly to Decius’ reign and adopted one of his surviving sons, in the course of time he became afraid that revolutionaries might recall Decius’ kingly virtues and bestow the empire on his son. So Gallus plotted his death, without the slightest regard for his adoption or for propriety” (Zos. 1.25, transl. Ridley 2017).

That Hostilianus's and Trebonianus Gallus's co-rule did not last more than a few weeks finds some support in the papyri from the province of Egypt. The first and last record of both emperors side by side on papyrus dates to August 13 of the first year of their rule – that is, 251 CE.Footnote 37 This first year of their joint rule would have ended on August 31, 251 CE. Hostilianus, however, was probably already dead by the end of this month because we have another papyrus dated to “year one” of the emperors Trebonianus Gallus and his son Volusianus.Footnote 38 The editors date this “year one” from September 1, 251 CE to August 31, 252 CE, but, since we have another papyrus dated to a “year three” of the two emperors in power until August 253 CE,Footnote 39 “year one” of Trebonianus and Volusianus must refer to the period before August 31, 251 CE. Moreover, there seems to have been a short time in the latter half of August 251 CE when Hostilianus was already out of the picture and Volusianus had not yet been named co-emperor: an Oxyrhynchus papyrus is dated to “year one” of the emperor Trebonianus Gallus without mentioning any co-emperor. It must belong to the turbulent weeks before August 31, 251 CE.Footnote 40 It thus seems likely that Hostilianus died in the second half of August 251 CE; however, the place and nature of his death, whether in Rome or Viminacium, and whether of disease or murdered by his colleague, remain uncertain.

Back to the epidemic and Rome: according to Zosimus, the disease arrived in the city when Hostilianus was already out of the picture. As it ravaged the population, Trebonianus Gallus and his son Volusianus gained popular support by providing proper burials for its victims even among the poor (Zos. 1.26). Zosimus's report must be given some credibility, as he is said to have largely relied on the lost history of the Athenian historian Dexippus, a contemporary of the Cyprianic Plague. Zosimus actually gives the most detailed account of the spread of the epidemic in the Roman Empire during the reign of Trebonianus Gallus, and provides us with very interesting additional information about its origins. While Harper places the first outbreak of the disease in 249 CE,Footnote 41 according to my reading of Zosimus the disease only made its first appearance under Trebonianus Gallus. Moreover, Zosimus's sources locate its first outbreak – contrary to Harper's account – in the regions affected by the renewed Scythian invasions: in other words on the Danube, in Lower Moesia, and in Asia Minor, rather than in Egypt:

Gallus was so lax in his administration, however, that the Scythians first threw the provinces adjoining them into chaos, and then devastated all the countries right down to the coast. There was not one province in the Roman Empire which was left undamaged, and they took nearly every unwalled city and most of the fortified ones as well. With war thus pressing heavily on the empire from all sides, a plague afflicted cities and villages and destroyed whatever was left of mankind: no plague in previous times wrought such destruction of human life (Zos. 1.26, transl. Ridley 2017).

Greek historians of Late Antiquity used “Scythians” as a catch-all term for the Gothic tribes from the steppe north of the Black Sea who fought on horseback, not the historical Scythians described by Herodotus who flourished from the 7th to the 3rd c. BCE in the Black Sea steppe. The Goths had arrived on the Pontic-Caspian steppe presumably from Scandinavia in the 2nd c. CE.Footnote 42 These marauding tribes may have been the same ones with whom Trebonianus Gallus had concluded a treaty in summer 251 CE. Zosimus lumped the Goths, the Borani, the Urugundi, and the Carpi (tribes at home in the regions north of the Lower Danube) together as Scythians who invaded the adjacent Roman territories and plundered whatever was still left (Zos. 1.27 and 1.31).

Zosimus thus appears to connect the origin of the pestilence with renewed Scythian invasions of Roman territories in 252/3 CE. His subsequent references to the disease, addressed below, likewise focused on the Danube, Lower Moesia, and Asia Minor. On the basis of the available evidence, therefore, it would seem that the disease appeared initially on the Balkan front and spread from there across the Empire. The contemporary 13th book of the Oracula Sibyllina – written from an Alexandrinian Christian/Jewish perspective between 264 and 267 CEFootnote 43 – corroborates the timeline passed down by Zosimus: Decius and his sons died before the disease started to wreak havoc within the Roman Empire:

Eutropius, writing around 369/70 CE, strengthens my dating by placing the first appearance of the disease firmly in the reign of Trebonianus Gallus – erroneously conflating Gaius Valens Hostilianus Messius Quintus, son of Decius, with Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus, and stressing the devastating power of the pestilence by employing three different terms for the same disease: “Subsequently Gallus Hostilianus, and Volusianus, the son of Gallus, were chosen emperors. … They achieved nothing at all remarkable. Their reign was notable only for the plague, diseases, and afflictions (pestilentia et morbis atque aegritudinibus) (Eutr 9.5, transl. Bird Reference Bird1993).Footnote 44

The Chronicle of Jerome, a translation into Latin of Eusebius of Caesarea's Chronicle, also dates the arrival of the pestilence to the reign of Trebonianus Gallus, referring to Dionysius and Cyprian as witnesses for outbreaks in Alexandria and Carthage: “A pestilential sickness seized many provinces of the whole world, and especially at Alexandria and in Egypt, as Dionysius writes, and the book On Mortality by Cyprian is a witness” (Jer. Chron. p. 219a Helm (anno 2269), 258th Olympics, transl. Pearse et al. 2005, 303).

The Armenian translation of Eusebius's Chronicle, like Jerome's, equally places the pestilence after Decius's death, showing that it was Eusebius, not Jerome, who dated it to the reign of Trebonianus Gallus and further validating my dating.Footnote 45 The Chronicle dates the first outbreaks of the Plague of Cyprian in Carthage and Alexandria simultaneously to 253 CE. Orosius, a Christian historian from the early 5th c. CE, emphasizes the pervasiveness of the pestilence, calling it basically a pandemic that affected all regions of the Empire, but (following Eutropius) wrongly identifies Hostilianus, the son of Decius, with Trebonianus Gallus:

In the thousand seventh year after the founding of the City, Gallus Hostilianus seized the throne as the twenty-sixth emperor after Augustus, and with difficulty held it for two years with his son, Volusianus. Vengeance for the violation of the Christian name spread out and, where the edicts of Decius for the destruction of churches circulated, to those places a pestilence of incredible diseases extended. Almost no Roman province, no city, no house existed, which was not seized by that general pestilence and laid bare. Gallus and Volusianus, famous for this plague alone, were killed while carrying on a civil war against Aemilianus … (Oros. 7.21.5–6, transl. Deferrari Reference Deferrari1964).

Later on in his History against the Pagans, Orosius again places the beginning of the epidemic in the reign of Trebonianus Gallus and Volusianus:

Here in Rome, likewise, under Gallus and Volusianus who had succeeded the persecutor, Decius, who had met his death early, a seventh plague arose from the poisoning of the air. This pestilence throughout all the confines of the Roman Empire, from the east into the west, not only gave over to death almost the entire human race, but also “poisoned the lakes and infected the grass” (Oros. 7.27.10, transl. Defferari Reference Deferrari1964).

Orosius's poisonous airs and pestilent waters are reminiscent of Bishop Dionysius's complaint to Hierax about “the air, reeking everywhere with the evil exhalation” and the pestilent “mist from the ground,” “breezes from the sea,” “airs from the rivers,” and “vapors from the harbors” that eventually brought on the pestilence in Alexandria.Footnote 46 By quoting Vergil's verse about a cattle plague in Italy (Verg. G. 3.481), Orosius seems to imply that humans also spread the infection to their animals – unheard of in any other source for the Cyprianic Plague − an idea which Harper speculates Orosius found in the account of Philostratus.Footnote 47

Aside from Bishop Dionysius of Alexandria, Bishop Cyprian of Carthage was an eyewitness to the pestilence. One of Cyprian's sermons addressed to the Christian community at Carthage contains a detailed description of the symptoms of the disease; modern scholarship has therefore named the pestilence after him. Cyprian is held to have composed his De mortalitate in 253 CE in the middle of the outbreak in Carthage.Footnote 48 The Cyprianic pseudo-epigraphical De laude martyrii belongs to the same circle around Bishop Cyprian of Carthage, and also mentions the pestilence, highlighting the unusual symptoms formerly unknown from other infectious illnesses and the high death toll.Footnote 49 Cyprian's biographer, Pontius of Carthage, remembered the pestilence a few years later as a most gruesome event invading every house and carrying off numberless people.Footnote 50 Orosius considers the pestilence a punishment for the persecutions of Christians initiated by Decius and points out that the duration of the epidemic was contemporary with the 15-year reign of Gallienus between 253 and 268 CE.

The Excerpta Salmasiana II from the 10th c. CE, Symeon the Logothete from the late 10th c. CE, the Byzantine chronicler of the 11th-c. CE George Cedrenus, and Zonaras, the Byzantine chronicler of the 13th c. CE, provide a very similar description of the epidemic reminiscent of Orosius.Footnote 51 However, they are the first who report that the pestilence originated in Ethiopia, probably all relying on the same lost tradition, which makes Harper conclude:

Numerous sources, all probably descending from Philostratus, locate the origin of the disease in “Ethiopia.” Of course, from Thucydides’ day “Ethiopia” was the cradle of diseases, but the fact that the disease appeared in Alexandria at least a full year before Rome and Carthage adds credence to this detail.Footnote 52

I find it rather futile to speculate with Harper whether this source might have been the 3rd-c. CE historian Philostratus of Athens, of whose existence and work we know so little; it might have rather been a much later Byzantine chronicler mingling the historical account of this pestilence with classic plague topoi. Harper rightly notes that Ethiopia had been the putative origin of many epidemics since Thucydides's description of the Athenian plague.Footnote 53 This alternative tradition thus does not provide a solid argument that the Cyprianic Plague might have started there. Ethiopia in ancient historiography meant the region south of Egypt in landlocked Africa around the source regions of the River Nile. Harper's reconstruction of the spread of the disease from inner Africa via the Nile to the Mediterranean follows these Byzantine chroniclers − without mentioning different accounts in the earlier sources and using the highly unlikely dating discussed above for Dionysius's letters as further validation.

After its initial outbreak, the pestilence reappeared in several waves around the Mediterranean. Zosimos, who had placed the first outbreak of the disease in the context of the Scythian invasions in the reign of Trebonianus Gallus in 251/2 CE, mentions another outbreak among Valerian's troops marching from Antioch to Cappadocia in 259 CE, drawing almost certainly on the lost text of the Athenian Dexippus. Zosimus reports that more than half of the men infected died of the disease.Footnote 54 As discussed above, it was also in 259 CE that Dionysius of Alexandria mentioned that a recent outbreak of the disease caused many among the members of his clergy to die, a reference Harper did not include.Footnote 55 Then, according to Zosimus, the disease reached Illyricum during the same period and ravaged with unprecedented violence the cities recently captured by Gothic invasions; here again Gothic raids are connected with a renewed outbreak of the epidemic.Footnote 56

According to the Justinianic historian Peter the Patrician, writing in the 6th c. CE and having as his source probably Dexippus, the disease broke out in spring 260 CE among Valerian's soldiers who were fighting against the Sassanians, and the contingent from Mauretania was particularly heavily affected.Footnote 57 Valerian's troops were stationed at that time in northern Mesopotamia near Edessa, one of the frontier cities in the province of Osroene. Zosimus, who is the only other extant source for this episode, knows nothing, however, of an epidemic among Valerian's army in Mesopotamia.Footnote 58 For the year 262 CE, the Historia Augusta reports that about 5,000 people a day were dying in Rome and the cities of Greece, possibly reflecting the perspective of Dexippus from the Greek mainland.Footnote 59 The philosopher Plotinus, who was born in Lykopolis in Lower Egypt, but later moved to live in Rome, was witness to the devastation of “the pestilence” (τοῦ λοιμοῦ) in the city; the epidemic even took the lives of his massage therapists.Footnote 60 Porphyry attests elsewhere that the city of Rome suffered for multiple years under this epidemic.Footnote 61

Probably the same wave of the disease devastating the population of Rome in 262/3 CE is mentioned by Aurelius Victor.Footnote 62 In spring 263 CE, according to my redating of the letter discussed above, Bishop Dionysius is lamenting recurrent pestilences and a tremendous loss of men in Alexandria.Footnote 63 During what was possibly the final recurrence of the disease in August 270 CE, Zosimus reports that the pestilence also attacked the barbarians and took the life of Emperor Claudius.Footnote 64 Again, we have references to the Scythians and to the Danube provinces for this last documented outbreak of the epidemic, which this time seems to have wreaked more havoc among the Gothic tribes than in the Roman army.Footnote 65 Aurelius Victor, on the other hand, was ignorant about the cause of Claudius's death. Zonaras reports that Claudius fell ill in Sirmium after a hard winter followed by famines that took a toll on the Roman troops. Eutropius merely speaks of a disease that carried Claudius off within two years of the beginning of his reign, but does not give further details.Footnote 66

Several authors agree that some regions experienced recurrent outbreaks of the pestilence. Evagrius Scholasticus transmits a passage from the lost contemporaneous history of Philostratus of Athens: “for Philostratus is surprised that the plague of his time lasted fifteen [years].”Footnote 67 This passage is critical for Harper's claim that Philostratus did write about the Plague of Cyprian. Zonaras, who also reports that the pestilence lasted 15 years,Footnote 68 might have gained this knowledge from Evagrius or directly from Philostratus. While the pestilence is attested for the period between late 251 and 270 CE, the “15 years” of Philostratus might thus refer to an Athenian experience of the disease recurring in multiple waves during one and a half decades. Also appealing is the explanation that the period of Gallienus's rule, which lasted 15 years from 253 to 268 CE, was associated by the biased contemporary historians with the years of the pestilence.Footnote 69

A seasonality of the Cyprianic Plague is reported by the Byzantine chronicler Symeon the Logothete, who asserts that the disease started in the autumn and abated at the rising of the Dog Star in July/August.Footnote 70 The connection between the abating of one wave with the rising of Sirius, the Dog Star, could also, however, simply have been a topos. Diodorus Siculus, writing in the 1st c. BCE, asserts that the sacrifice made at the time of the rising of Sirius brought an end to outbreaks of pestilential diseases.Footnote 71

In sum, according to my reading of the sources, the disease made its first appearance on the Balkan front, not in Egypt, and reached many regions all over the Empire, from the Balkans to Greece, the major harbors of the Mediterranean, including Rome, Carthage, and Alexandria, and the Roman military headquarters in Illyricum, Asia Minor, and Osrhoene, over a duration of almost 20 years from 251/2 to 270 CE. Certain regions such as Rome, Athens, Alexandria, and the Balkan fronts were reportedly touched several times over these two decades.

The numismatic evidence

The numismatic evidence for the Plague of Cyprian is considerably less straightforward and thus more difficult to interpret than the literary sources. Harper invokes coins of Trebonianus Gallus that show Apollo Salutaris, salutary health-giving Apollo, on their reverses as evidence for the Plague of Cyprian as early as the second half of 251 CE. It was the mint in Rome that struck Apollo Salutaris on coins minted under Trebonianus Gallus of a type dated, by circular reasoning, with reference to the alleged death of Hostilianus from the pestilence in fall 251 CE.Footnote 72 However, these coins could originate from any point during the reign of Trebonianus Gallus, from summer 251 to summer 253 CE. Harper's argument that Apollo Salutaris's imagery might be connected to a pestilence does, however, fit the fact that coins of Volusian, Aemilian, and Valerian I, all of whom ruled during the epidemic, also show Apollo Salutaris.Footnote 73 Gallienus and Claudius Gothicus portray Apollo with the legend Salus Aug(ustorum), praying for the health of the emperors.Footnote 74

However, the invocation of Apollo as the healing god was nothing new. Apollo Medicus had a temple in Rome from the 5th c. BCE and features prominently in Augustan poetry.Footnote 75 Moreover, the emperors during the third quarter of the 3rd c. CE seem to have had a particular affinity to Apollo, who appears as Apollo Conservator on the coins of Aemilian, Valerian, Gallienus, Claudius Gothicus, Quintillus, and Aurelian,Footnote 76 as Apollo Propugnator on the coins of Valerian and Gallienus,Footnote 77 and as Apollo Palatinus on the coins of Gallienus.Footnote 78 Apollo is shown without any legend on coins of Herennius Etruscus and Hostilianus as principes iuventutis.Footnote 79 He also features without any epithet, but with his attributes – a laurel branch and a lyre – on coins of Gallienus and Aurelian.Footnote 80 Coins referring to Salus publica, invoking the physical health of the Roman people, were also minted in the 3rd c. CE, during the reigns of Macrinus, Hostilianus, Valerian, Gallienus, Tacitus, Florian, and Probus, some of whom did not rule during the Plague of Cyprian.Footnote 81 Moreover, the healing god Aesculapius appears on coins of Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Gallienus, Claudius Gothicus, and Aurelian.Footnote 82

In sum, in my opinion Apollo Salutaris and recurrent depictions of Salus publica and Aesculapius on coins over the centuries are evidence for concern for health, but not necessarily for an epidemic. Harper adopts an extreme position by referring to the numismatic evidence as “attesting a major outbreak of disease in the middle of the 3rd c.” – a maximalist interpretation that overinterprets our data.Footnote 83 The association of the appearance of Apollo Salutaris on coins with the Cyprianic Plague remains possible but hardly definite; drawing any conclusions from these coins about the extent of the epidemic means giving in to the temptation to overstretch the evidence.

The papyrological evidence

From Dionysius's letters, we learn that Alexandria was hit by several distinct waves of the pestilence, with one striking in 258/9 and another in 262/3 CE. According to Eusebius's Chronicle discussed above, the first wave seems to have hit Alexandria in 253 CE and to have spread to the Egyptian hinterlandFootnote 84 – an important specification that his Church History does not contain. Whether the pestilence ever reached beyond the densely populated quarters of Alexandria is a matter of contestation. So far, no papyrological evidence dates unequivocally to the time span of the Cyprianic Plague, even though papyrological documentation for the 3rd c. CE is dense and continuous.Footnote 85 Compared to 10,443 documentary papyri loosely dated to the 1st c. CE and 25,903 loosely dated to the 2nd c. CE, we have 25,086 for the 3rd c. CE.Footnote 86 We can therefore hardly speak of a dark century, at least as far as Middle and Upper Egypt are concerned. Should we thus not expect to find multiple references among the papyri to a mass mortality event of that scale? By comparison, multiple securely dated papyri make reference to the Antonine Plague, the plague under Maximinus Daia, and the Justinianic Plague and potentially also the Hadrianic Plague.Footnote 87 Harper refers to papyri documenting the Plague of Cyprian from the city of Oxyrhynchus in Middle Egypt without discussing their content further.Footnote 88 As he gives little consideration to the papyrological evidence, I will discuss extant testimonies in more detail below.

The only papyrus (P.Merton 1.26) from the 3rd c. CE that refers to an infectious disease and can be securely dated – the appointment of a guardian for a little orphan girl from Oxyrhynchus whose parents had both died of the “shivering disease” (ἀπό τινος φρ{ɛ}ικώδους νόσου τɛτɛλɛυτηκότων) – was written on February 8, 274 CE, so it does not fit the timeline of the Cyprianic Plague. Moreover, the so-called “shivering disease” is generally identified as malaria.Footnote 89 However, some other papyri refer to some form of infectious disease potentially related to the Plague of Cyprian, although these are only roughly dated to the 3rd c. CE based on their handwriting style.

In a letter on papyrus, POxy. 14.1666, dated to the 3rd c. CE for paleographic reasons, a certain Pausanias writes to his brother Heracleides that he had heard that an infectious disease was spreading in the region of Oxyrhynchus: “I beg you to write to me, my brother, about your safety, because I heard in Antinoopolis that in your region [i.e., the Oxyrhynchite] a pestilence (λοιμὸς) was spreading.”Footnote 90 Pausanias was traveling down the Nile, probably from Thebes or Coptos in Upper Egypt all the way to Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast, a journey that comprised nearly 900 km. When he reached Antinoopolis in Middle Egypt, he thought about making a stop to visit his brother in Oxyrhynchus, which lay 100 km further north. Because of rumors of a pestilence he refrained from doing so. Interestingly, the pestilence seems to have been limited to the region of Oxyrhynchus, while all other towns and cities which Pausanias passed through on his journey down the Nile remained untouched, which would be highly unusual if we were dealing with the very contagious Plague of Cyprian here.

Another papyrus found in Oxyrhynchus (PSI 4.299), a private letter, recounts some severe condition (νόσος) that befell several members of the same family. The letter writer, Titianus, reports that such a severe sickness had befallen him that he had been unable to move and – even though he had recovered – he was still suffering from infected, purulent eyes and pain in all parts of his body. Titianus's father, his mother, and all children of the family had also been infected but had recovered.Footnote 91 Titianus's description of the afflictions is very similar to the symptoms described by Cyprian of the plague of his time: “The pain in the eyes, the attack of the fevers, and the ailment of all the limbs.”Footnote 92 Titianus's festering eye infection reminds us in particular of Cyprian's description of “eyes … on fire with the injected blood,” which sometimes led to the loss of the sufferer's eyesight.Footnote 93 The letter of Titianus has been dated paleographically (but also because of its vague references to Christianity) to the late 3rd c. CE and could therefore possibly refer to the Plague of Cyprian but also to the infectious disease outbreak limited to the Oxyrhynchite region mentioned in the previous papyrus letter.

Another papyrus letter, PStras. 1.73, of unknown Egyptian provenance and roughly dated by its editor to the 3rd c. CE, speaks about “a large pestilence” (νόσος μɛγάλη) that befell an entire family and caused a small boy to die: “After you had left us, we came down with a serious disease, I … and their children, [and] little Mimos died and my whole foot is infected from the illness.” Again, we might have a reference here to our pestilence, for Cyprian also speaks of infected feet or parts of the limbs: “that in some cases the feet or some parts of the limbs are taken off by the contagion of diseased putrefaction.”Footnote 94

Potentially referring to a pestilence is the letter from a certain Lykarion to his father, Psonthuonsi, who is traveling abroad (Stud. Pal. 22.33). The son urges his father, who had been gone for quite some time, to return home. He tells his father that many members of their household had died this year – he speaks of “much dying” (πολλὴ θνῆσις). In the aftermath, most of the surviving family members had decided to leave.Footnote 95 However, neither the provenance of the letter is known nor its dating – the 1st c. CE, but also the second half of the 2nd c. or the 3rd c. CE have been suggested − which leaves it open whether this great mortality has anything to do with our epidemic.

The same expression, “a great dying” (μɛγάλη θνῆσις), is also used in another papyrus letter, PMich. 8.510, found in Karanis in the Fayum, but probably sent from Alexandria. Its dating is equally uncertain. Here the letter writer, a woman named Taeis, reports about the many deaths that happened in Alexandria ([ἐ]π<ɛ>ὶ μɛγάλη θνῆσ[ις γέ]γονɛ ἐν Ἀλɛξανδρίᾳ). This letter has been dated to the late 2nd or 3rd c. CE; “the great dying” in Alexandria could thus refer to the Antonine or Cyprianic Plague, but also to any other violence such as local uproars, persecutions, or civil war, all of which were often reported for Alexandria.Footnote 96

Furthermore, among the papyri from 3rd-c. CE Roman Egypt happens to be the largest coherent group of documents from the Roman Empire, consisting of roughly 1,000 papyri, dating exactly to the two decades that frame the Plague of Cyprian and that otherwise constitute the darkest decades of the Roman Empire, as far as the availability of source material is concerned. Documents from the so-called Heroninus archive offer in-depth insights into the running of a Roman estate from roughly 250 to 270 CE.Footnote 97 This landed estate was owned by Aurelius Appianus, a Roman knight who belonged to the imperial elite and held a city councillorship in Alexandria.Footnote 98 Appianus's estate was managed by a certain Heroninus, after whom the archive is named. Heroninus oversaw the day-to-day running of Appianus's land in Theadelphia from September 249 to summer 268 CE, when he was succeeded by his son Heronas. Appianus's lands in other regions of the Fayum were managed by colleagues of Heroninus, with whom he corresponded regularly. The central administration was located in the district's capital, Arsinoe, and consisted of men from the local elite who were city councilors and medium landowners in their own right. In their roles as Heroninus's superiors, they also feature frequently in the archive. However, no signs could be detected that the estate of Appianus had been affected by a demographic or economic crisis during the decades from 250 to 270 CE. The region was vigorous and heavily monetized at least until 270 CE, when the Heroninus archive breaks off.Footnote 99

In sum, symptoms portrayed in at least two papyri dating to the 3rd c. CE resemble the disease described in detail by Bishop Cyprian of Carthage in his treatise De mortalitate and potentially confirm that the epidemic did reach beyond Alexandria. The papyri do not, however, offer any direct support for a mass mortality event on a scale such as Harper envisions in the Egyptian hinterland around the middle of the 3rd c. CE.

The archaeological evidence

Archaeology has so far added relatively little to our understanding of this epidemic. A mass grave from the catacomb of Saints Peter and Marcellinus in Rome has been adduced by Harper as potential material evidence for the impact of the Cyprianic Plague in the city.Footnote 100 In more recent publications not considered by Harper, the excavators interpret the excavated and partially excavated rooms (X80/T16, X82/T18, and X78/T15) differently: instead of a one-time burial, these publications argue for a careful interment over a number of years to decades between the middle of the 2nd c. and the early 3rd c. CE. In addition, the excavators stress the careful and very elaborate handling of the dead bodies, with plaster, resin, and amber and remains of gold and silver adornments, unknown for other mass burials resulting from an epidemic.Footnote 101 They argue that the burial place might have been reserved for members of a community whose funeral practices are found in the Near East and North Africa and who might have been the first Christians of the city – their burial ground might have formed the primitive pole of the vast underground Christian funerary space of Saints Peter and Marcellinus which was later created at the end of the 3rd c. and beginning of the 4th c. CE.

The catacomb also comprises a number of unexcavated rooms (X80, X81, X83, and X84), a later addition to the central portion of the catacombs, where preliminary soundings have revealed large body assemblages.Footnote 102 A coin of Gordian found in X81 points to a terminus post quem of 238 CE, which leads Harper to speculate that the mass burial might be connected to the Plague of Cyprian. However, as long as excavations at the site do not progress, this identification of the bodies with plague victims remains just speculation.

The same doubts arise concerning the funerary site excavated at Roman Egyptian Thebes, where in a layer of slaked lime in one Theban tomb (TT37, Tomb of Harwa and Akhamunru) remains of human skeletons were discovered by the Italian Archaeological Mission to Luxor and adduced by Harper as possible evidence for a mass burial at an entry point of the plague in the Upper Nile region.Footnote 103 According to the first reports published by the excavation director, Francesco Tiradritti, in 1998, funerary equipment dating from the Ptolemaic period to the 3rd and 4th c. CE was found under the slaked lime layer, which does not support a dating of the incineration site to the middle of the 3rd c. CE, but rather suggests a date in the 4th c. CE or later.Footnote 104 In 2014, Tiradritti published an article in Egyptian Archaeology in which he interpreted the corpses as an effort to quickly dispose of plague-infected individuals connected to the Cyprianic Plague.Footnote 105 According to this article, 3rd-c. pottery and 3rd/4th-c. oil lamps narrowed the date further to the middle of the 3rd c. CE, a surprising conclusion that would need to be backed by the more detailed excavation reports. Moreover, given the lack of C-14 analysis, it is unclear whether the corpses actually date from the same period as the lime kilns. In the lime kilns the burnt remainder of decorative elements of limestone (identified as parts of the cenotaphs of Harwa and Akhimenru) were found. The human remains from earlier periods of the tomb might have similarly served as fuel for the lime kilns. It is worth noting that other lime production sites containing human remains have been found in Egypt: monastic communities from the 4th c. CE onwards are known to have burned limestone from ancient tombs for other building projects, and mummies and their coffins were used to fuel the fires.Footnote 106 Again, the archaeological evidence for a mass mortality event around the middle of the 3rd c. CE is thus hardly conclusive.

Conclusions

Based on a detailed reading of the available evidence, I have suggested some important revisions to Harper's narrative of the origin and evolution of the 3rd-c. CE epidemic. The first mention of the Cyprianic Plague falls, in fact, not in the beginning of the reign of Decius (249–51 CE), but in the reign of Trebonianus Gallus (251–53 CE). The literary sources recording the events of the 250s and 260s CE point to a disease that saw its first outbreak in the Empire among Roman troops fighting in Moesia and on the Danube in an effort to repel Scythian invasions. The pandemic's first documented victim may have been Hostilianus, the teenage son of Decius who allegedly died from the pestilence, although a different tradition has it that he was in fact murdered by his co-emperor, Trebonianus Gallus.Footnote 107 Since no mention of disease is made in the aftermath of the battle of Abritus in July 251 CE, it seems more reasonable to see the onset of the epidemic as coinciding with the renewed invasions of the Goths. It may well have reached the Roman Empire via incursions by steppe people from central Eurasia into Roman territories and then traveled with the Roman army to Mediterranean ports such as Rome, Carthage, Athens, and Alexandria, before possibly spreading further into the hinterland of these cities. In this light, we cannot consider the onset of the epidemic as an impetus for the edict commanding sacrifices released by the emperor Decius in 249 CE, as Harper has speculated.

The more important point is that there is little evidence to support the theory that the disease appeared first in Ethiopia in the late 240s CE and then slowly traveled down the Nile to Alexandria and from there across the Mediterranean to Rome, as Harper has suggested. My reading of the sources thus essentially refutes the theory that Egypt's southern border was the entry point for the pandemic. While the 6th-c. CE Justinianic Plague seems to have irrupted first in Pelusium on the Egyptian Mediterranean coast, it possibly traveled there from China via the Indian Ocean and up the Red Sea.Footnote 108 It is also worth noting that multiple Late Medieval and Early Modern diseases repeatedly reached Egypt chiefly via the Mediterranean, through the movement of goods, people, and, at least in some cases, rodents. During the Middle Ages and Early Modernity, the southern route from Sudan seems to have played little part in the transmission of disease, and the sources for the 3rd c. CE do not give the impression that the pattern then was significantly different.Footnote 109

Estimating the plague's impact on the history of the Empire during the turbulent middle decades of the 3rd c. CE seems impossible, given the general dearth of evidence from one of the darkest periods of the Roman world. Harper argued that the Cyprianic Plague had “significant social, economic, political and cultural ramifications,” but this remains a question for debate, since the sources do not easily lend themselves to such a wide-reaching interpretation.Footnote 110 While the epidemic undoubtedly exacerbated the political and military crisis of the third quarter of the 3rd c. CE, it should probably not be considered as the root of the crisis itself, as Harper has suggested.

Harper rightly terms it a pandemic though, that spread over the entire Mediterranean world. As is so often the case, this pandemic was probably very disparate in its impact – heavily affecting some densely settled cities or cramped military camps, while sparing more rural areas. It seems highly likely that the port city of Alexandria would have been more severely affected than its remote hinterland, and the same was probably true for other major cities. If we believe that the reports of Bishop Dionysius, the Historia Augusta, and Cyprian on mortality rates in Alexandria, Rome, and Carthage can be taken at face value, then the pandemic may have weakened the major capitals of the Empire and Roman army camps at the frontiers at a critical juncture. Zosimus reports that, during its first appearance on the Balkan front, the disease also spread to the cities and villages and took many lives (Zos. 1.26.2). Again, in Illyricum during another wave of the disease in 259 CE, Zosimus relays that many cities were affected and depopulated (Zos 1.37.3). Papyri from 3rd-c. CE Egypt contain a handful of references to an infectious disease with symptoms similar to those described by Cyprian for the pestilence in Carthage; but unfortunately none of these texts bear a date that would allow us to connect them securely to the Plague of Cyprian.

Yet, the wealth of extant papyrological evidence for Middle Egypt for the two decades of the Cyprianic Plague provides no support for any demographic, economic, or social disruption in the Egyptian hinterland. Nor have mass tombs yet been identified from any part of the Roman world that clearly date to the years of the Cyprianic Plague, and which would corroborate Harper's claim for an Empire-wide mass mortality event. While the numismatic, archaeological, and papyrological evidence is thus at best inconclusive, epigraphic evidence is entirely lacking. If anywhere, we should search in the provinces of Moesia, Dalmatia, and Pannonia for further evidence among the epigraphic and archaeological record of excess mortality during those two decades.

Similar to the Antonine Plague a century earlier, identifying the pathogen of the Cyprianic Plague remains a puzzle to be solved. Based upon the surviving evidence, the disease seems to have been highly contagious. Harper suggested a viral haemorrhagic fever diagnosis, such as Ebola.Footnote 111 Like every tentative diagnosis of a Roman epidemic, however, this remains up in the air unless and until remnants of ancient DNA are isolated from skeletons spatiotemporally coincident with reports of the 3rd-c. pandemic – a difficult task, as a virus that killed its host swiftly is exceptionally difficult to characterize from ancient DNA. The vast necropolis of the military camp with over 13,000 graves at Viminacium in Moesia Superior, headquarters of the Roman army during the battles against the Goths under Trebonianus Gallus, might be a place to start genomic work, especially since the Archaeological Park of Viminacium (Serbian Kostolac) claims to show the mausoleum of the first plague victim, the emperor Decius's teenage son, Hostilianus.

Acknowledgments

I owe thanks to the anonymous reviewers of JRA for their constructive criticism and suggestions for improvements. My thanks also go to David J. DeVore and Brandon McDonald for their very helpful comments. Finally, this article benefited greatly from the valuable feedback I received on an earlier version from the audiences at the Climate Change and History Research Initiative annual colloquium, “Resilience, environmental change and society: perspectives from history and prehistory,” at the Max-Planck Institute in Jena in March 2019, and at the Princeton University virtual series, “Pandemics in the past: from prehistory to (almost) the present,” in May 2020.