Introduction

International standards have proliferated in many policy areas over recent decades and are a key feature of global governance (Abbott and Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal2001; Mattli and Büthe Reference Mattli and Büthe2003; Mattli and Woods Reference Mattli and Woods2009). Standard-setting is particularly consequential in finance given its global reach and systemic implications for the economy. The post-2008 crisis literature on the international governance of finance (for some representative works, see Ban et al. Reference Ban, Seabrooke and Freitas2016; Helleiner Reference Helleiner2014; Helleiner et al. Reference Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018; Moschella and Tsingou Reference Moschella and Tsingou2013; Mügge and Perry Reference Mügge and Perry2014; Newman and Posner Reference Newman and Posner2018) has mainly investigated the issuing of new rules after the crisis (for example, Brummer Reference Brummer2015; Gabor Reference Gabor2016; Knaack and Gruin Reference Knaack and Gruin2020; Quaglia Reference Quaglia2020; Young Reference Young2012; Rixen Reference Rixen2013; Thiemann Reference Thiemann2018; Zaring Reference Zaring2020). The few works that have considered weak cases of global standard-setting have tended to deal with a single set of rules. For example, Thiemann (Reference Thiemann2014) considers the exclusion of shadow banking from the Basel Accords, Knaack and Gruin (Reference Knaack and Gruin2020) investigate epistemic contestation concerning digital finance in key international fora, whereas Rixen (Reference Rixen2013) accounts for the ineffectiveness of post-crisis regulatory reform of offshore financial centers. There is also surprisingly little scholarship on failed or negative cases of standard setting in finance – that is, cases of non-agreement and issues that are largely absent from the agenda of global bodies. Moreover, a systematic comparative analysis of multiple cases of weak or negative global rules remains a significant gap in the literature.

In this article, we examine weak and negative cases of international standard-setting (henceforth, we just refer to “weak” cases for simplicity). We acknowledge that there are a potentially infinite number of such cases, not least because international standard-setting is more often than not a long, complex, and contested process. Yet, most financial services are now subject to some degree to international soft law, which has proliferated since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 (Brummer Reference Brummer2015; Newman and Posner Reference Newman and Posner2018; Zaring Reference Zaring2020). Moreover, our focus is on “most likely” cases of international regulation – namely, financial entities and activities that have systemic implications for financial stability, generate significant cross-border externalities, and create opportunities for international regulatory arbitrage.

The cases we examine are all in the area of “shadow banking” to minimize sources of sectoral variation. Shadow banking refers to the system of non-bank financial intermediation or market-based finance, and typically includes a range of entities (such as hedge funds and money market funds) and activities (like securitization and repo markets) (FSB 2011). The sector is a most likely case of post-crisis standard setting because of the significant and well-documented role that it played in amplifying the international financial crisis (Ban et al. Reference Ban, Seabrooke and Freitas2016; Gabor Reference Gabor2016; Rixen Reference Rixen2013; Thiemann Reference Thiemann2018). Shadow banking also came under increasing regulatory scrutiny in response to the rapid expansion of the sector after 2008 (Ban and Gabor Reference Ban and Gabor2016; Gabor Reference Gabor2016), underscoring the need for strengthening domestic and international governance (Engelen Reference Engelen and Nesvatailova2018; Woyames Dreher Reference Woyames Dreher2019). In recent years, there have been renewed financial stability concerns regarding shadow banks’ exposure during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading central banks to provide unprecedented liquidity support to the sector (Tooze Reference Tooze2021). For instance, the former deputy governor of the Bank of England, Paul Tucker, has lamented the failure to reign in the risk of shadow banking, calling for comprehensive regulation of the sector (Financial Times, 7 August 2022).

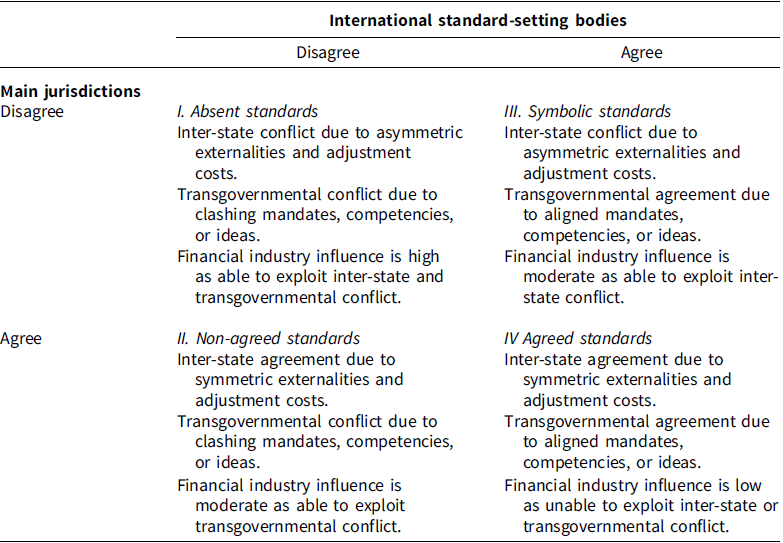

We argue that there is no a priori theoretical reason why international standard-setting should be more difficult than in other financial services. Rather, the wide variation in weak international standards in shadow banking that we observe is an empirical phenomenon to be explained. To systematically account for these outcomes, we integrate an inter-state explanation, which focuses on competition between major jurisdictions, with a transgovernmental explanation, which relates to conflict between different regulatory bodies at the international level. We also consider how these dimensions create conditions for and interact with financial industry lobbying. This allows us to construct a typology of distinct types of weak international standards: (1) absent standards, (2) non-agreed standards, (3) symbolic standards, and (4) agreed standards. The framework is then illustrated through a structured focused comparison of four different cases of shadow banking regulation.

The paper makes a significant contribution to scholarship on the governance of global finance by helping to delineate the scope conditions for international standard-setting and unpacking the interaction effects of inter-state and transgovernmental divisions. Beyond finance, it also generates new insights into the capacity of powerful economic interests to exploit multi-level regulatory conflicts. Finally, in the conclusion, we outline why our typology could potentially be applied to other regulatory fields to explain absent or weak standards, including data privacy, environmental protection, pharmaceuticals, and public health.

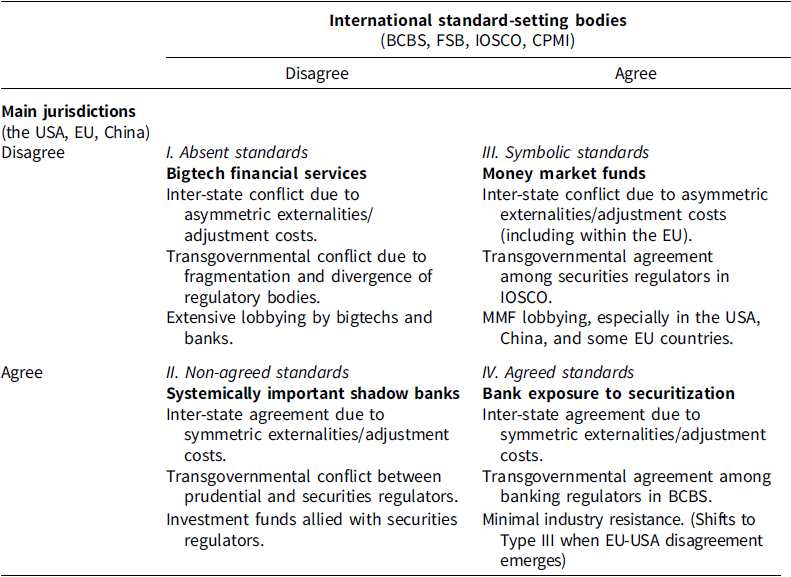

The article proceeds as follows. The next section reviews the existing literature and alternative explanations of international standard-setting, as well as detailing our analytical framework and methodological approach. The following sections then examine four regulatory cases in shadow banking – so as to keep several contextual factors constant across cases – corresponding to the four quadrants in our explanatory typology: ‘bigtech’ financial services (“Type I – absent standards”), systemically-important financial institutions (“Type II – non-agreed standards”), money market funds (“Type III – symbolic standards”), and bank exposure to securitization (“Type IV – agreed standards). The concluding section reflects on the wider contribution and application of our arguments.

Explaining international standard-setting

International standards are non-legally binding “soft laws” issued by transgovernmental bodies that generally bring together domestic regulatory agencies worldwide. This paper does not focus on the specific content of standards, but rather on their creation and robustness. We identify four possible outcomes of interest, thus creating a typology of standards for heuristic purposes: (I) absent standards, whereby there is only minimal discussion of certain issues and no substantive proposals are tabled; (II) non-agreed standards, in which detailed rules are proposed, but eventually not agreed; (III) symbolic standards, whereby only minimalist rules with a low level of precision and stringency are issued; and (IV) agreed standards with a relatively high level of precision and stringency. Nonetheless, even in this positive case, standards are not necessarily stable. On the contrary, new sources of conflict could lead to standards being weakened (type III) or abandoned (type II).

Existing explanations put forward by the literature on the politics of international standard-setting do not satisfactorily account for the four-fold typology we have identified. A historical institutionalist explanation would stress the path-dependent nature of global rule-making (Farrell and Newman Reference Farrell and Newman2010; Fioretos Reference Fioretos2010; Posner Reference Posner2009, Reference Posner2010, Reference Posner, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018) and the degree of “institutionalisation” (Newman and Posner Reference Newman and Posner2018) of global standard-setting bodies. From this perspective, once international rules are set, they become “locked in” through positive feedback effects and lobbying by vested interests; conversely, the absence of pre-existing rules serves as a barrier to standard-setting in the future. Moreover, a historical institutionalist explanation would posit that long-standing and well-resourced regulatory fora are better positioned to set international standards (Newman and Posner Reference Newman and Posner2018; Posner Reference Posner, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018). By contrast, rule-making is less likely in areas of finance characterized by weaker global bodies and/or fragmented responsibilities (Mügge and Perry Reference Mügge and Perry2014). Yet, this historical institutionalist explanation does not account for the variation of regulatory outcomes across shadow banking because in all the cases we examine, there are neither a dedicated international body, nor prior standards.

Second, inter-state scholarship would highlight the interests and power of the main jurisdictions in regulating global finance. For instance, Simmons (Reference Simmons2001) argues that the USA is the leading jurisdiction and, thus, international standard-setting is a function of the negative externalities resulting from non-adherence to the US rules and market incentives for the emulation of the US rules. Whenever there are insignificant negative externalities for the dominant financial center (the USA), no international standards will be set. Whenever there are significant negative externalities for the USA, the nature of international regulatory harmonization will vary depending on the incentives that other countries have (or not) to emulate the US rules. Taking a less US-centric perspective, Drezner (Reference Drezner2007) considers the “great powers” – defined as jurisdictions with a large domestic market, namely, the USA and European Union (EU) – and argues that international standard-setting in finance is a function of the interest convergence of the great powers, and the interest divergence between the great powers and other countries. In this case, great power conflict leads to either sham standards (where conflict with other actors is also high) or rival standards (where conflict with other actors is low, enabling great powers to form alliances with other jurisdictions). By contrast, great power agreement is likely to be conducive to club standards or harmonized standards, depending on the preferences of other countries.

We argue that both explanations in isolation are problematic in two respects. First, Simmons’s framework downplays the multipolar context of international standard-setting, most notably with respect to the increasing coherence and influence of the EU since the global financial crisis. While Drezner acknowledges the USA and EU as “great powers,” the status of China in the framework remains ambiguous. Second, neither framework considers the autonomous agency, preferences, or influence of transgovernmental regulatory agencies. We argue that these exerted an increasingly important and independent causal effect in shaping international standards since 2008.

Existing typologies also fail to provide a clear set of expectations regarding shadow banking. In the case of large investment funds, for instance, Simmons’s framework would predict that high negative externalities (arising from extensive cross-border activity) should lead to either market harmonization or political harmonization. Similarly, low conflict between the USA and EU over investment funds should generate club standards or harmonized standards, according to Drezner’s framework. But in neither case do these predictions accord with the failure to agree with international standards, as we detail below. Simmons’s framework also performs poorly in the case of “bigtech” finance because the combination of insignificant externalities (owing to the EU not hosting any large bigtech firms) and high market incentives to emulate (due to EU dependency on the US bigtechs) should lead to decentralized market harmonization – for which we find no evidence. By contrast, while Drezner’s framework helps to explain great power conflict over bigtechs, the influence of “other international actors” – including China – is ambiguous. Moreover, we find little evidence of either sham standards or rival standards as we would expect from increasing US-EU tensions.

A further inter-state explanation put forward by Singer (2004) posits that the trade-off between financial stability and the competitiveness of the domestic financial sector drives global standard setting. On the one hand, it could be argued that the fact that large shadow banking institutions have not yet caused a crisis, and are increasingly subject to stringent domestic regulation in some jurisdictions, might account for the weakness of international standards. On the other hand, however, financial regulators at the national, regional (EU), and international levels have repeatedly warned about the financial instability risks arising from the rapid growth of shadow banks since the global financial crisis. For example, central bankers have long highlighted the dangers of the impact of a “run” on a large investment fund (Constâncio Reference Constâncio2014; Haldane Reference Haldane2014; Tarullo Reference Tarullo2015), while multiple studies have raised concerns about both the systemic and operational risks arising from the growth of bigtech finance (Bains et al. Reference Bains, Sugimoto and Wilson2022; Ehrentraud et al. Reference Ehrentraud, Evans, Monteil and Restoy2022; Panetta Reference Panetta2021). At the very least, policymakers are acutely aware of the apparent trade-off between stability and competitiveness in these areas.

Finally, the business power literature points to the capacity of the powerful financial industry to potentially resist or substantially weaken international standards (Baker Reference Baker2010). For example, existing studies highlight the role of financial lobbying in undermining global rules on derivatives prior to the crisis (Pagliari Reference Pagliari2012; Knaack Reference Knaack2015) and agreement on industry-friendly standards, as in the case of Basel II (Young Reference Young2012). Since 2008, however, financial power was seriously weakened by the mobilization of powerful consumer groups and financial activists (Howarth and James Reference Howarth and James2023; Pagliari and Young Reference Pagliari and Young2014) and the empowerment of regulators with new prudential tools (Baker Reference Baker2013; Bell and Hindmoor Reference Bell and Hindmoor2015). Hence, multiple studies have shown that the financial industry has frequently failed to resist or object to international agreement on tougher international standards (Quaglia Reference Quaglia2014; Young Reference Young2012). Moreover, the shadow banking sector is arguably more fragmented and thus less well organized to resist global standards, at least compared to the banking sector. It is therefore all the more surprising that the international regulatory response has been so timid.

When considered in isolation, the above explanations of global standard-setting are inadequate in explaining the empirical record. To address this, we argue that critical insights from different theoretical perspectives need to be integrated in a systematic way.

Our explanation: inter-state and transgovernmental conflicts

Our framework focuses on the importance of both inter-state and transgovernmental conflict in shaping international standard-setting. The first theoretical approach we draw upon is an inter-state perspective, which assumes that international standards reflect the preferences of the main jurisdictions, namely, the USA, the EU, and, increasingly, China (Drezner Reference Drezner2007; Helleiner 2014; Quaglia and Spendzharova Reference Quaglia and Spendzharova2017; Rixen Reference Rixen2013; Simmons 2001; Singer Reference Singer2007). Crucially, the interests of the largest jurisdictions are assumed to be the key determinant of the likelihood, scope, and content of global rule-making. It follows that inter-state agreement – namely, the alignment of the preferences of major financial jurisdictions – makes the setting of international standards more likely, while inter-state conflict makes standards less likely.

The inter-state scholarship suggests that the incentives that large jurisdictions have to promote and agree on international standards are determined by two main factors: the concentration and distribution of cross-border externalities (Simmons Reference Simmons2001); and the adjustment costs borne by the domestic industry across jurisdictions (Drezner Reference Drezner2007). Negative cross-border externalities occur when financial entities or activities based in a certain jurisdiction cause harmful effects to third parties based in other jurisdictions. Hence, if certain financial services are concentrated in particular jurisdictions (e.g. hedge funds, which are mostly based in the USA and the UK), but produce negative externalities in third countries, there will be fewer incentives for the home state to agree to international standards. This is because its domestic financial industry would bear the brunt of adjustment costs – that is to say, the costs of complying with new more stringent rules – in order to limit negative externalities for others. However, critics note that state-centric perspectives downplay the extent to which national regulators are themselves embedded in complex institutional architectures and regulatory networks at the transnational level (Bach and Newman Reference Bach and Newman2014). We, therefore, need to incorporate the role of powerful global bodies as independent actors in their own right.

The second dimension of our explanation adopts a transgovernmental perspective, focusing on the role of “technocratic regulators” – i.e. domestic (unelected) officials who meet in international sectoral standard-setting bodies – in promoting international regulatory harmonization (Brummer Reference Brummer2015; Newman and Posner Reference Newman and Posner2018; Zaring Reference Zaring2020). A particularly dense global institutional architecture has developed for issuing “soft law” in finance and includes the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the BCBS, the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), and the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI). Studies suggest that these transnational policy communities (Tsingou Reference Tsingou2015) and networks of experts (Broome and Seabrooke Reference Broome and Seabrooke2015; Broome et al. Reference Broome, Homolar and Kranke2018; Seabrooke and Tsingou Reference Seabrooke and Tsingou2014) have common professional and educational backgrounds and shared epistemological views, thereby facilitating agreement on international standards.

We expect that where the preferences of different global regulatory bodies are aligned, agreement on international standards is more likely; conversely, where there is conflict between regulatory bodies, standards are less likely. Recent scholarship on regulatory conflict finds that transgovernmental disagreement can arise as a consequence of clashes over jurisdictional mandates and policy competencies (Bach et al. Reference Bach, De Francesco, Maggetti and Ruffing2016; Busuioc Reference Busuioc2016; Lombardi and Moschella Reference Lombardi and Moschella2017), as well as contrasting regulatory ideas and approaches (Ban et al. Reference Ban, Seabrooke and Freitas2016; James and Quaglia Reference James and Quaglia2022; Kranke Reference Kranke2020). It follows that technocratic conflict over international standards is more likely where a range of sectoral regulatory bodies are involved (for example, see Gabor Reference Gabor2016; Knaack and Gruin Reference Knaack and Gruin2020).

The final part of our explanation considers how the interaction of financial industry lobbying with inter-state and transgovernmental conflict is causally significant for the likelihood of international standard-setting. We start from the assumption that international standard-setting in finance is highly contested and leads to the mobilization of multiple actors and coalitions for and against reform (Baker Reference Baker2010; Bell and Hindmoor Reference Bell and Hindmoor2015; Pagliari and Young Reference Pagliari and Young2014; Young Reference Young2012; Young and Pagliari Reference Young and Pagliari2015). Our contribution here is to better specify the conditions under which organized financial interests are likely to prevail (or not) in resisting, weakening, or diluting new international standards. We expect that when major jurisdictions and/or regulatory bodies are divided, the financial industry will be able to exert greater leverage over regulatory outcomes. This is because lobbyists can exploit conflict through divide-and-rule tactics, by “venue shopping” to find sympathetic countries or bodies, and by forming strategic alliances with like-minded officials (for example, see Helleiner et al. Reference Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018; Howarth and James Reference Howarth and James2023; Lall 2012; Newman and Posner Reference Newman and Posner2018). By contrast, when states and/or global bodies are in agreement, there is far less scope to exploit divisions among policymakers. Our explanatory typology enables us to specify the degree of financial industry influence in each case. All else being equal, we expect financial industry influence to be high under conditions of both inter-state and transgovernmental disagreement; to be low under conditions of inter-state and transgovernmental agreement; and to be moderate when conflict is either between states or transgovernmental bodies.

Our framework integrates the above variables – inter-state and transgovernmental conflicts, and their interaction with financial lobbying – into a two-by-two matrix to systematically account for different types of weak cases of international standard-setting in finance (see Table 1). The explanatory leverage of our typology is illustrated by examining four post-crisis cases in shadow banking. By examining cases in a single policy area, we can minimize potential sources of sectoral variation that might affect the outcomes of interest. We consider the EU as a state-like jurisdiction (or actor) in international affairs (Drezner Reference Drezner2007, 35–9) because, over time, financial governance in Europe has shifted to the EU level: national legislations mostly reflect harmonized EU rules, EU-level bodies coordinate national-level supervision and have some direct supervisory power (see Mügge Reference Mügge2010; Quaglia Reference Quaglia2010). However, we remain mindful of how the EU differs from states.

Table 1. An explanatory typology for weak international standards in finance

Our analysis draws on multiple data sources. We conducted twelve semi-structured interviews between 2020 and 2022 with financial regulators and industry practitioners located at the domestic, EU, and international levels (located in London, Frankfurt, Brussels, Basel, and Washington) (see anonymized list of interviewees in the bibliography). To minimize problems of potential bias and exaggeration by respondents, we adopted two strategies. First, we interviewed a cross-section of practitioners from different jurisdictions and regulatory bodies in order to corroborate individual claims. Second, our interview findings were triangulated with publicly available documents and a systematic survey of press coverage. The results are detailed in the following sections (and summarized in Table 2) which provide a systematically structured focused comparison of four post-crisis cases in shadow banking.

Table 2. Applying the analytical framework to the case of shadow banking

Type I – absent standards: “bigtech” financial services

The first type of weak case concerns the absence of international rules, defined by minimal discussion and the failure to develop detailed proposals in global standard-setting bodies. An important example relates to the provision of financial services by “bigtech” firms – that is, large companies that provide digital services – such as e-commerce, social media, and telecommunications – via digital platforms. Although developments in bigtech finance have accelerated in recent years, concerns regarding the implications of platform technology for financial intermediation have been around much longer and parallel the post-2008 growth of shadow banking. As early as 2011, for example, prominent central bankers noted that large technology firms, like Google, had the potential to transform payment services (Khan Reference Khan2011; Padmanabhan Reference Padmanabhan2012) and posed a profound challenge to established banks (Spencer Reference Spencer2014). By 2015, central bankers were increasingly outspoken about the perceived threat posed by the “big 5” US bigtech firms. Yves Mersch, member of the ECB Executive Board, warned that “Payment services are incorporated seamlessly into [bigtech] digital ecosystems and thus potentially have global reach” (Mersch Reference Mersch2015). Tellingly, he called for international solutions, concluding that global service providers offering global products presented a “further challenge that has to be tackled.”

Over the past decade, regulatory concerns about bigtech finance have crystallized around three core issues. The first relates to the implications for systemic risks and financial stability. According to the FSB (2019), while bigtech can potentially contribute to “financial inclusion,” particularly in developing economies, it also brings well-established problems of financial intermediation, including “leverage, maturity transformation, and liquidity mismatches, as well as operational risks.” These challenges are compounded by the systemically important size of bigtech companies – notably market leaders like Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft in the USA and Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent in China. By exploiting economies of scale, it is feared that bigtechs could develop into critical financial infrastructures or “ecosystems” operating outside the traditional banking system, rendering them “too-big-to-fail on steroids” (interview H).

The second issue is competition – namely, the capacity of bigtech firms to challenge and potentially threaten the position of established banks. In particular, it is claimed that platform companies could potentially leverage their large customer base, access to data, and network advantages to establish a “platform bank” providing the full range of product lines – from payments to deposits, credit provision, and wealth management (Stulz Reference Stulz2019). Third is the potential for bigtechs to exploit regulatory arbitrage. This arises from the “blurring of boundaries” between finance and social media, and the use of different tools, methodologies, and interfaces by bigtech firms (interview G). At the same time, payment services remain largely outside the purview of prudential regulation, while credit provision creates risks akin to those of shadow banking. Moreover, senior regulators note that while several bigtech financial activities fall within the existing perimeter of activity-specific financial regulation, this becomes more problematic at scale when these activities have systemic implications (Panetta Reference Panetta2021).

To avoid prudential oversight, the US bigtechs have thus far tended to focus on profitable activities, like payment services, in collaboration with established US banks. By contrast, China has actively fostered financial innovation through the development of globally competitive national “tech” champions (Knaack and Gruin Reference Knaack and Gruin2020). For instance, Alipay – a subsidiary of Ant Financial within the Alibaba group – is now one of the largest mobile payment company in the world, operates one of the largest money market fund in the world (Yu’e Bao), and owns an online bank (MYbank). In recent years, however, Chinese authorities have begun to crack down on the activities of this previously largely “uncontrolled” sector (Financial Times, 4 October 2021).

But the possibility of agreeing international standards on bigtech finance is severely limited by inter-state conflict, rooted in the competing interests and divergent regulatory regimes of the main jurisdictions. As home to the largest bigtech firms, the USA and China are keen to defend their interests by resisting the development of new international standards – the adjustment costs of which would be borne by themselves, while the benefits would accrue also to third countries. Conversely, the main proponents of tougher international rules are European countries. Senior regulators acknowledge that this is largely driven by geopolitics – namely, “anti-American and anti-Chinese sentiment” (interview G). Specifically, EU policymakers seek to use international fora to address cross-border externalities generated by USA and Chinese bigtech, and to minimize competition with established European banks and fintech industry. Nonetheless, inter-state conflict is also apparent within Europe: while Germany, Austria, Italy, and Portugal tend to be “conservative” on regulation, Ireland, the Baltics, and Malta are more “progressive.” France and Spain tend to side with the former, but favor light-touch regulation at home to attract bigtech firms, while the UK (outside the EU) favors “anodyne” standards (interview G). Similar divisions characterize the main EU institutions – with the ECB and the European Securities and Markets Authority prioritizing financial stability, while the European Commission is keen to support a home-grown digital industry – thus weakening the EU’s voice in international fora.

These divisions are compounded at the international level by transgovernmental conflicts between different regulatory bodies. These have divergent mandates, objectives, and regulatory approaches with respect to bigtech finance, including prudential issues (BCBS), investor protection (IOSCO), and market infrastructure (CPMI). The FSB tries to act in a coordinating role but is often constrained by disagreements between central bankers concerned with upholding prudential rules, and finance ministers more sensitive to growth and competitiveness (interview L). Bigtech is also subject to turf fights over definitional issues: for example, while central bankers view digital assets as money, securities regulators regard them as securities, leading to divergent regulatory prescriptions. These fault lines are compounded by the involvement of a range of other regulatory agencies – notably those concerned with data privacy, telecoms infrastructure, and cybersecurity – which generate new obstacles to international coordination. Consequently, bigtechs often find themselves in “regulatory limbo” as regulators struggle to play “catch up” (interview I).

Inter-state and transgovernmental conflict has been widely exploited by industry stakeholders. On the one hand, the largest digital platforms wield a formidable lobbying capability at the global level and allied with sympathetic US Government officials to push back against any attempt to set international standards (interview I, L). By contrast, the established banking industry – led by the Institute of International Finance (IIF) – found itself in alliance with central bankers in pushing for the extension of prudential rules to new entrants (interviews J, K). Moreover, European banks worked with their home governments to counteract resistance from US bigtechs to new EU legislation in this area. The result of this confluence of multiple organized interests with inter-state and transgovernmental conflict is that agreement has thus far been limited to minimal declaratory statements (for example, see BIS 2021; FSB 2020).

Type II – non-agreed standards: systemically-important financial institutions

Our second type of weak case relates to international standards that are proposed and negotiated, but not agreed upon. We illustrate this by examining the fate of global rules concerning global systemically important financial institutions (henceforth “G-SIFIs”), including shadow banks. These are financial institutions whose distress or disorderly failure would cause significant disruption to the wider financial system because of their size, complexity, and systemic interconnectedness. The vast majority of G-SIFIs are located in the USA and, to a lesser extent, in the EU and the UK. On the one hand, the adjustment costs resulting from the introduction of new rules on G-SIFIs would be mainly concentrated in these jurisdictions, whereas the potential benefits – in the form of avoiding negative externalities from the failure of G-SIFIs – would extend to third countries. On the other hand, however, the USA and the UK are particularly worried about G-SIFIs because these countries host large financial sectors and financial institutions whose failure would be devastating for the national economy. There was therefore significant inter-state agreement as the interests of the USA and UK, supported by the EU, favored the development of new international standards in this area (interviews, A, B).

At the Seoul Summit in 2010, the Group of Twenty, under the leadership of the USA and the UK, and in agreement with the EU, endorsed the FSB’s framework for reducing the systemic and moral hazard risks posed by G-SIFIs. The implementation of the framework required, as a first step, that assessment methodologies should be devised to determine which institutions were to be designated as G-SIFIs, and thus potentially subject to more stringent prudential regulation and supervision. Although joint work between the FSB and IOSCO began in 2014, it soon became apparent that this was hampered by transgovernmental conflict. On the one hand, prudential regulators in the FSB feared that large investment funds could pose similar systemic risks to global banks. In particular, there was concern about the likelihood and impact of a “run” on a large investment fund, stemming from the fact that funds gave investors the possibility to withdraw their money on a daily basis but often invested in illiquid assets. Additional concerns were related to the concentration of the asset management sector and the increasing size of the largest funds, such as BlackRock and Vanguard, which now rivaled that of the biggest banks (Haldane Reference Haldane2014).

By contrast, securities regulators in IOSCO were less concerned about the systemic risk and argued that attempts to extend prudential tools to investment funds were based on a flawed logic. For example, the chairman of IOSCO, Greg Medcraft (Reference Medcraft2015), criticized the proposed adoption of regulatory tools from banking and insurance as “inappropriate” because they were “developed to deal with firms which have different risk profiles to asset managers. It is like creating a square peg for a round hole.” Instead, he insisted that as day-to-day “frontline regulators,” securities regulators had a better understanding of the industry. Another regulator suggested that “bank regulators do not understand asset management…[or] how good asset managers manage a fund” (interview E). Importantly, IOSCO and several of its members (including the US Securities and Exchange Commission [SEC]) also sat on the FSB (albeit outnumbered by prudential regulators), so their opposition had direct implications for the FSB’s work. As a result, the early negotiations were described as “fraught” as they were hampered by “disjointed agendas” and “rigid regulatory frameworks” that regulators struggled to adapt to the non-bank financial sector (interviews D, C).

Transgovernmental conflict was compounded by industry lobbying. Investment funds engaged in a concerted push to prevent rules that would label them as systemically important, mounting ferocious lobbying against the FSB-IOSCO’s (2015) proposals for assessment methodologies for non-bank, non-insurer G-SIFIs. For example, the ICI (2015) and the IIF (2015) argued that asset managers were not a source of systemic risk and did not believe that size alone was an appropriate criterion to assess the systemic relevance of investment funds. Significantly, the ICI (2015) also explicitly criticized the framing of investment funds by prudential regulators as “shadow banks”: “We have strenuously objected to the characterization of all portions of the financial system other than banks as mere ‘shadow banks’ – a term that describes this FSB workstream and that betrays the kind of bank regulatory ‘group think’ that pervades the current consultation.” In doing so, securities regulators increasingly allied with the investment fund industry at the global level. Indeed, IOSCO regulators felt that industry was “on their side,” and that working together “strengthened” their hand and enabled them to form a “pincer movement” against the FSB (interviews E, F).

The alliance proved to be a potent force. IOSCO Chairman Greg Medcraft (Reference Medcraft2015), and the head of the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority, Martin Wheatley, both acknowledged that IOSCO had been influenced by the critical response of the industry (Financial Planning, 22 June 2015). Prudential regulators also complained at the time about the influence of investment fund lobbyists over securities regulators as “proof that a problem exists” (interview A). The result was that securities regulators were able to successfully stall and ultimately weaken efforts to subject large investment funds to prudential regulation. Prudential regulators subsequently signaled a retreat, as the FSB and IOSCO decided to postpone the finalization of the assessment methodologies for shadow banks.

Type III – symbolic standards: money market funds

An example of agreement on symbolic international standards (Type III) – arising from inter-state conflict with transgovernmental agreement – concerns the regulation of money market funds (MMFs). These are investment funds that have a “diversified portfolio of high-quality, low-duration fixed-income instruments” (IOSCO 2012a, 1). In the USA and EU, MMFs serve as an important source of funding for governments, financial institutions, and businesses. In China, MMFs mainly provide funding to non-financial companies and savers often invest in MMFs, rather than bank deposits (Sun Reference Sun2019). When international standards on MMFs were first discussed in 2012, the industry had approximately $4.7 trillion of assets under management, with the majority of MMF assets held in the USA (53%), China (18%), Ireland (9%), France (6%), and Luxembourg (6%) (IOSCO 2012a). Adjustment costs to new international rules would therefore predominantly fall upon these jurisdictions, while externalities linked to the activities of MMFs involved third countries. This generated significant inter-state disagreements over the desirability and design of international standards on MMFs.

The global financial crisis ignited regulatory concerns over the systemic risks posed by large MMFs. But the inter-state conflict this generated was frequently leveraged by vocal industry groups urging policymakers to defend the competitiveness of the sector. In the USA, securities regulators in the SEC proposed several changes to strengthen the regulation and supervision of MMFs. But this provoked fierce opposition from the USA industry, which eventually succeeded in killing off the proposed reforms. Similarly, the EU advocated more stringent post-crisis regulation of MMFs, not least because two-thirds of the dollar-denominated funding provided by US MMFs to European banks disappeared in 2011. As Emil Paulis, a senior Commission official, put it “We are very disappointed that, in the USA, MMFs have not yet been successfully regulated by the SEC…. We regret what is happening there and we do not intend to follow that route” (cited in Financial Times, 30 September 2012).

But negotiations on EU legislation were riven by inter-state conflict from the start, which industry was eager to exploit. Disagreement centered on the methods used to value MMF asset portfolios: specifically, reliance on “variable net asset value” (NAV) approaches that use mark-to-market accounting, or a “constant” NAV approach which relies on amortized cost accounting. In France, MMFs were already regulated according to the variable NAV approach and regulators sought to include similar rules in EU legislation and the IOSCO’s policy recommendations. Edouard Vieillefond, a senior official at the French Autorité des Marchés Financiers, stated that he was in favor of a “ban on constant NAV funds, or at least for a set of strong prudential rules” (cited in Ricketts 2012). The UK echoed this position, as the Bank of England argued that constant NAV MMFs should either become regulated banks or variable NAV funds (Tucker Reference Tucker2010). It called for global standards or, at least, a “globally consistent approach”s because many MMFs were based in the USA, but they were internationally active, lending to banks, corporates, and sovereigns around the world. In May 2012, Paul Tucker suggested that the EU should act unilaterally, unless the USA reformed the MMF sector (Financial Times, 4 May 2012).

But the push by British and French regulators was opposed by several other EU member states – notably Ireland and Luxembourg – which sought to defend the attractiveness of their jurisdictions for the MMF sector. Consequently, internal divisions, compounded by the absence of EU legislation (at the time), undermined the EU’s collective influence in international debates. Further opposition to IOSCO’s proposals came from China, which boasted a thriving but lightly regulated MMF industry. Chinese funds employed constant NAV accounting methods and the impact of the 2008 crisis was limited, so regulators were wary of any international standards that could constrain the sector’s growth (Woyames Dreher Reference Woyames Dreher2019). Internationally, the China Securities Regulatory Commission and the Chinese MMFs industry association opposed precise and stringent international standards, taking the unusual step of submitting a joint response to the IOSCO’s consultation (China Securities Regulatory Commission and Chinese MMFs Association 2012).

IOSCO (2012a) published its Policy Recommendations on MMFs in early 2012 and invited interested parties to respond to the public consultation. Opponents did not consider MMFs as systemic vehicles and challenged their inclusion in the shadow banking system. The possibility of a mandatory move from constant NAV to variable NAV was criticized, stressing that it would likely result in massive outflows from MMFs. Other proposals, such as the establishment of private insurance, were considered unfeasible (IOSCO 2012a). The final version of IOSCO’s (2012b) policy recommendations included 15 key principles for valuation, liquidity management, use of ratings, and disclosure to investors.

However, the international standards eventually approved were weak and lacked both precision and stringency. They included a range of proposals, such as the possibility of moving to variable NAV or increasing capital and liquidity buffers for funds that did not adopt variable NAV. However, jurisdictions were free to choose which approach to adopt. Many policy options that had been mentioned in the IOSCO’s consultative paper (2012a) were eventually discarded – including the mandatory move to variable NAV, the use of capital buffers for MMFs (especially those based on constant NAV), and the possibility of subjecting MMFs to bank-like regulation. Other potential requirements were weakened or made optional – such as the use of “redemption gates” permitting funds to limit redemptions for a short period of time during market stress (Woyames Dreher Reference Woyames Dreher2019). Hence, broad agreement amongst securities regulators in IOSCO was ultimately insufficient to overcome inter-state conflict and MMF industry lobbying, resulting in largely symbolic standards.

Type IV – agreed standards: bank exposure to securitization

International standards related to bank exposure to securitization provide further corroboration of our argument. In particular, the case demonstrates the importance of inter-state and transgovernmental agreements for the development of new global rules characterized by high precision and stringency that significantly restricts financial activities. Critically, however, the case of securitization also illustrates how and why international standards can break down over time. In particular, shifting regulatory preferences in the main jurisdictions, or among different regulatory bodies, can undermine pre-existing agreements by generating new sources of divergence or conflict, leading standards to be weakened (Type III) or abandoned (Type II).

During the negotiations on the Basel III Accord that set capital and liquidity requirements for banks, the USA and UK led global efforts to strengthen bank capital requirements, including for securitized products. The EU supported these changes in principle, although member states disagreed over the precise level and definition of new capital rules (Howarth and Quaglia Reference Howarth and Quaglia2013). In 2014, the Basel III Accord, which had been agreed upon in 2010, was supplemented by a revised framework for securitization that substantially increased bank capital requirements on securitized products.

We argue that agreement was ultimately possible because transgovernmental and inter-state conflict was minimal, thereby reducing the effectiveness of industry lobbying. On the one hand, banking regulators took the lead in setting bank capital rules, including those for securitization, which limited the possibility of bureaucratic turf wars or regulatory clashes. On the other hand, the relatively even distribution of banking activity across the two main jurisdictions (the USA and EU) served to ameliorate sources of potential inter-state rivalry as this meant cross-border externalities and adjustment costs would be broadly symmetric. Although the USA has the largest market for securitization worldwide, the UK dominated the securitization market in Europe, and the EU was keen to support the development of these markets at home. All the main jurisdictions, therefore, had a powerful incentive to maintain a level of regulatory playing field. This also meant that at that time there was little scope for organized financial interests to exploit either regulatory or political divisions, and thus there is little evidence of concerted industry opposition to the proposals (Young Reference Young2013).

Yet, this consensus proved to be short-lived. Soon after the Basel III Accord was agreed upon, the EU and the UK took the lead in seeking to revive the securitization market in Europe. Following the crisis and the imposition of more stringent regulation, the level of securitization in the EU dropped significantly as banks preferred to tap central bank facilities for funding (Financial Times, 9 May 2013). Efforts to revitalize the market focused on Europe’s bank-based financial system, meaning that securitization could be used by banks to increase lending to the real economy without increasing their capital requirements. But it would also encourage small and medium-sized enterprises to bypass banks by securitizing their own assets and selling them on corporate debt markets (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Gabor and Hubner2018).

Central bankers in Europe were also keen to revive securitization because they relied on these markets in the conduct of monetary policy (Braun Reference Braun2020). Similarly, the ECB regarded the asset-backed securities market as an important component of the collateral framework of the Eurosystem. The Bank of England supported these efforts on the grounds that banks could use securitization to diversify their funding and transfer risk on underlying loans, while non-banks could also finance lending through securitization (Rule 2015). Both central banks became increasingly vocal in pushing for reduced capital requirements for safe securitization. Yves Mersch, a member of the ECB’s Executive Board, was critical of how higher capital requirements introduced after 2010 were calibrated on the worst-performing securitized products, likening the move to “calibrating the price of flood insurance on the experience of New Orleans for a city like Madrid” (cited in Financial Times, 1 October 2014).

The EU and UK led global efforts to reform the regulation of securitization by increasing the transparency and standardization of securitized products while weakening bank capital requirements for less risky securitization (Quaglia Reference Quaglia2021). In May 2014, the Bank of England and the ECB (2014) published a joint paper regarding the impaired securitization market in the EU. At the same time, the European Bankin Authority issued a discussion paper on simple and transparent securitization. Subsequently, securitization became a key component of the project for the Capital Markets Union in Europe (Braun Reference Braun2020; Braun et al. Reference Braun, Gabor and Hubner2018).

Problematically, the EU’s decision to unilaterally relax its post-crisis rules on securitization immediately undermined the basis for inter-state agreement at the international level. To minimize the potential for increasing divergence of preferences between the two main jurisdictions (the USA and EU), international regulators responded by reviewing the standards on securitization agreed in 2014. The BCBS and the IOSCO established a joint Task Force on Securitization, which was co-chaired by David Rule, a senior official at the Bank of England, and Greg Medcraft, the Chair of the IOSCO, and which developed criteria to identify simple, transparent, and comparable securitization.

In parallel, the BCBS began work to lower bank capital requirements for safe securitization. Yves Mersch explained that the two central banks had a “common analysis and a common suggestion,” arguing that if new rules failed to gain traction at the international level, an EU-specific approach would be needed (Financial Times, 8 April 2014). To placate these demands, the BCBS (2018) revised capital requirements for securitization exposures, including the regulatory capital treatment for simple, transparent, and comparable securitization, and set additional criteria for differentiating the capital treatment of simple, transparent, and comparable securitization from other forms of securitization. Under the impulse of EU and UK regulators, these changes were subsequently extended to short-term securitization in subsequent BCBS-IOSCO guidelines (2018). Consequently, the prospect of increasing inter-state divergence between the USA and EU led regulators to gradually weaken international standards on securitization agreed in the wake of the crisis – thereby shifting the outcome closer to Type III (symbolic standards).

Conclusion

This article sets out to investigate weak or negative cases where international standards in finance are either perfunctory or non-existent. We integrated an inter-state explanation, which focuses on conflicts between major jurisdictions, with a transgovernmental explanation, which examines conflicts between different regulatory bodies at the international level. We also considered how these dimensions create conditions for and interact with financial industry lobbying. From this we generated a matrix with four distinct types of cases: (1) absent standards, (2) non-agreed standards, (3) symbolic standards, and (4) agreed standards. This was then tested through a structured comparison of four cases related to shadow banking, the results of which are summarized in Table 2.

We argue that the paper makes important scholarly contributions to three bodies of literature. The first relates to the governance of global finance (Brummer Reference Brummer2015; Newman and Posner Reference Newman and Posner2018; Thiemann Reference Thiemann2018; Zaring Reference Zaring2020). In particular, it addresses an important analytical lacuna – namely, the lack of a systematic account of how and why international standards are either absent or largely symbolic. These weak cases shed important light on barriers to international standard-setting and the conditions for successful agreement. Moreover, our typology can potentially be extended to other regulatory areas beyond finance. Indeed, we can foresee the primary explanatory variables – i.e. inter-state and transgovernmental conflict – being used to explain absent or weak standards in fields as diverse as data privacy, environmental protection, pharmaceuticals, and public health, which constitute interesting venues for further research. All of these economic sectors are likely to yield cases of significant variation in the main causal mechanisms outlined in our theory: namely, the distribution of negative externalities and the adjustment costs of standard setting, the extent of bureaucratic competition and clashing regulatory approaches, and the capacity of private interests to leverage and exploit regulatory conflict at the international level.

Second, the paper contributes to scholarship on multi-level governance by seeking to integrate state-centric (e.g. Drezner Reference Drezner2007; Helleiner 2014; Simmons 2001; Singer Reference Singer2007) and transgovernmental accounts (e.g. Bach and Newman Reference Bach and Newman2014; Broome et al. Reference Broome, Homolar and Kranke2018; Porter Reference Porter2014; Tsingou Reference Tsingou2015). Commonly, these approaches are posed in juxtaposition with the assumption that power is a zero-sum game located at the national or transnational levels. By contrast, we recognize that regulatory capacity is shared across multiple levels and institutional bodies. Incorporating both inter-state and transgovernmental conflict into our explanatory typology also provides a more systematic basis for understanding the interaction effects between the two variables. That is, by deriving and testing empirical expectations related to the confluence of these two factors, we are better placed to unpack the scope conditions for international agreement and provide new insights on the variability of possible outcomes on weak standards.

Third, our explanation helps to qualify assumptions about business power (Baker Reference Baker2010; Bell and Hindmoor Reference Bell and Hindmoor2015). Multiple studies demonstrate that finance frequently builds alliances with supportive non-financial groups, national governments, and/or regulatory agencies for and against new international standards (James and Quaglia Reference James and Quaglia2020; Lall 2011; Pagliari and Young Reference Pagliari and Young2014; Young Reference Young2012; Young and Pagliari Reference Young and Pagliari2015). But we know less about how industry lobbying interacts systematically with inter-state and transgovernmental conflict across different cases. We posit that the power of finance to resist, weaken, or dilute international standards is greatest when lobbyists are capable of exploiting divisions among major jurisdictions and/or regulatory bodies. By contrast, broad agreement on regulatory issues among the largest countries and relevant transgovernmental bodies serves as a powerful barrier to industry efforts to undermine the imposition of new rules. In doing so, the framework advances business power scholarship by better specifying the conditions under which financial lobbies “win” at the international level, but also by foregrounding the mediating role of political and regulatory conflict in shaping whether pro- or anti-standards coalitions are likely to prevail.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for their constructive feedback on an earlier draft of this paper. A previous version of this article was presented at the Conference of the Council for European Studies in Lisbon in June 2022. We thank the discussants, fellow panelists, and audiences for their comments and reactions. We are particularly grateful to Shawn Donnelly, Erik Jones, Manuela Moschella, Aneta Spendzharova and Amy Verdun for their comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Notes on contributors

Scott James is a Reader in Political Economy at Kings’ College, London, UK.

Lucia Quaglia is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Bologna, Italy (corresponding author [email protected]).