Introduction

Dynamic capabilities are second-order organizational capabilities aimed at achieving competitive advantage through generating and modifying firms' routines and practices (Zollo & Winter, Reference Zollo and Winter2002). Dynamic capabilities are especially relevant for achieving sustainable competitive advantage and maximizing long-term performance in changing and turbulent environments (Arndt & Bach, Reference Arndt and Bach2015; Corner & Kearins, Reference Corner and Kearins2018; Efrat, Hughes, Nemkova, Souchon, & Sy-Changco, Reference Efrat, Hughes, Nemkova, Souchon and Sy-Changco2018; Markovich, Efrat, & Raban, Reference Markovich, Efrat and Raban2021; Teece, Reference Teece2007, Reference Teece2012, Reference Teece2018a, Reference Teece2018b; Torres, Sidorova, & Jones, Reference Torres, Sidorova and Jones2018; Wang & Ahmed, Reference Wang and Ahmed2007; Williamson, Reference Williamson2016). They ‘enable the firm to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external resources to maintain leadership in continually shifting business environments’ (Teece, Reference Teece2014, p. 329). Previous studies have advocated the centrality of external information retrieved by firms in advancing their capabilities (Markovich, Efrat, Raban, & Souchon, Reference Markovich, Efrat, Raban and Souchon2019) and emphasized information management (Oliva, Couto, Santos, & Bresciani, Reference Oliva, Couto, Santos and Bresciani2019; Sher & Lee, Reference Sher and Lee2004), but it is not clear which types of information enhance dynamic capabilities and how. Empirical research on the nature of information sources and the paths by which they foster dynamic capabilities is still at a rudimentary stage, which is surprising given the surge of information availability in the current decade. Addressing this research gap is important, as there is an extensive need for accurate and relevant information for decision-making processes in this era of the information society (Dabrowski, Reference Dabrowski2018) and information overload (Saxena & Lamest, Reference Saxena and Lamest2018).

Teece and colleagues’ (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997; Teece, Reference Teece2007, Reference Teece2014, Reference Teece2018a, Reference Teece2018b) classification of dynamic capabilities is the most widely cited typology in this domain (Arndt, Reference Arndt2019; Benitez, Llorens, & Braojos, Reference Benitez, Llorens and Braojos2018; Jantunen, Tarkiainen, Chari, & Oghazi, Reference Jantunen, Tarkiainen, Chari and Oghazi2018; Tallott & Hilliard, Reference Tallott and Hilliard2016; Wilden, Devinney, & Dowling, Reference Wilden, Devinney and Dowling2016) and provides the basis for the current research. Teece's dynamic capabilities typology comprises three activities: sensing the environment to discover, learn, and rate opportunities; seizing opportunities; and reconfiguring for organizational transformation, often through innovation implementation. While previous studies acknowledge the relevance of external information to all three activities of dynamic capabilities (Sher & Lee, Reference Sher and Lee2004), sensing is most receptive to external information. According to Teece (Reference Teece2007), sensing involves investing in research, understanding customer needs, technological capabilities, latent demand, industry structure, and likely competitor's responses. These activities are all related to obtaining and using competitive intelligence or competitive information (Global Intelligence Alliance, 2004; Rodenberg, Reference Rodenberg2007; Wright & Calof, Reference Wright and Calof2006). As a system aimed at scanning the environment (De Almeida, Lesca, & Canton, Reference De Almeida, Lesca and Canton2016), competitive intelligence spans web-based information sources as well as human sources of information and intelligence (Calof & Wright, Reference Calof and Wright2008; Wright & Calof, Reference Wright and Calof2006). According to Teece (Reference Teece2007), sensing involves ‘available information in whatever form it appears’ (p. 1323); hence, previous work has concentrated on information as a resource (Bitencourt, de Oliveira Santini, Ladeira, Santos, & Teixeira, Reference Bitencourt, de Oliveira Santini, Ladeira, Santos and Teixeira2020) and neglected to differentiate between types and sources of information. By distinguishing between web-based and human information sources, we follow Liu and Yang (Reference Liu and Yang2020), who called for a better understanding of contributors of external resources. Furthermore, we explore how sensing mediates the effects of competitive information sources on seizing and reconfiguring.

Competitive intelligence using web-based sources is a dynamic, global, up-to-date, and available method of retrieving and analyzing high-quality information (Chen, Luo, & Wang, Reference Chen, Luo and Wang2017; Markovich et al., Reference Markovich, Efrat, Raban and Souchon2019). However, firms differ in their actual access to information and their abilities to turn it into actionable decision-making (Vaughan & You, Reference Vaughan and You2011). Before the exponential rise of the web, managers preferred cheap and informal human information channels (Souchon & Diamantopoulos, Reference Souchon and Diamantopoulos1999); however, web-based sources are now likely to play a role in building and improving dynamic capabilities alongside traditional human information sources. For example, firms may ‘listen’ and gather important customer information to improve decision-making not only through their sales representatives, but also by scanning discussions on social media (He et al., Reference He, Shen, Tian, Li, Akula, Yan and Tao2015). The assumption that both human and web-based information sources are antecedents of dynamic capabilities has not been empirically examined, a gap we wish to address.

This paper uses a mixed-methods approach comprising two studies. Study 1 analyzes in-depth field interviews with executive managers from 12 firms and concludes that web-based and human information sources have complementary roles in monitoring the firm's business environment and influencing all three dynamic capabilities. The results from study 1 reveal that sensing relies on various sources of information and plays an essential role in promoting seizing and reconfiguring. These findings are further substantiated in study 2, which draws on data from a survey of 139 senior managers. This research makes two contributions. First, following previous research which acknowledged that external information is crucial to dynamic capabilities (Kump, Engelmann, Kessler, & Schweiger, Reference Kump, Engelmann, Kessler and Schweiger2019), we provide evidence for the distinct and shared influence of web-based and human information sources in advancing the formation of dynamic capabilities. Second, in contrast to studies which tend to investigate dynamic capabilities as a given cluster, discussing their antecedents or consequences, we analyze inter-relationships among the three capabilities. We provide empirical evidence for the mediation effect of sensing on the impacts of web-based and human information sources on seizing and reconfiguring. To our knowledge, such a mediation effect is new.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: first, we introduce the theoretical background and formulate hypotheses, followed by a description of the mixed-methods approach and the details of studies 1 and 2. After presenting the findings, we conclude with a general discussion of the two studies, implications and limitations.

Theoretical background

Linking the use of information sources to dynamic capabilities

Competitive intelligence concerns the systematic collection of information about the external business ecosystem that could affect the firm's decisions, including information about customers, suppliers, competitors, products, and regulations (Kars-Unluoglu & Kevill, Reference Kars-Unluoglu and Kevill2021). There are two main types of information resources: (a) traditional competitive intelligence is information derived from human sources (Oakley, Reference Oakley2019), primarily employees, especially salespeople (Wright & Calof, Reference Wright and Calof2006) but also managers (Peng, Lockett, Liu, & Qi, Reference Peng, Lockett, Liu and Qi2022; Vézina, Selma, & Malo, Reference Vézina, Selma and Malo2019). Until the digital revolution of the mid-to-late 20th century, human information sources were the primary source of intelligence (Oakley, Reference Oakley2019); (b) publicly available information which nowadays comes mainly from the web (Naghshineh, Reference Naghshineh2008; Tropotei, Reference Tropotei2019). The growth of the web enables firms of all sizes to access information cost-effectively, but firms differ in their abilities to convert information into decisions (Fuld, Reference Fuld2010). Vaughan and You (Reference Vaughan and You2011) categorized web-based information into three main sources: firm websites, discussion spaces, and collections of web pages with hyperlinks for firms.

The role of competitive information in building dynamic capabilities derives from four knowledge processes, that are microfoundations of dynamic capabilities: (1) knowledge from external sources accumulates within organizations and undergoes renewal through experimental internal learning (Deng, Liu, Gallagher, & Wu, Reference Deng, Liu, Gallagher and Wu2020; Macher & Mowery, Reference Macher and Mowery2009; Shamim, Zeng, Shariq, & Khan, Reference Shamim, Zeng, Shariq and Khan2019). This external knowledge is considered hard to acquire, especially by small firms (Eriksson, Reference Eriksson2014). (2) Knowledge integration occurs by combining the knowledge accumulated from external and internal sources. Synchronization and consolidation of internal and external knowledge leverage the firm's dynamic capabilities (Eriksson, Reference Eriksson2014). (3) Knowledge utilization is critical, since unused data and information are either worthless (Markovich et al., Reference Markovich, Efrat, Raban and Souchon2019) or, at best, associated with latent worth, but is relatively neglected in the literature. Typical usage processes are codification and knowledge sharing. (4) Knowledge reconfiguration involves generating new combinations of existing knowledge or leveraging existing knowledge in new ways. Knowledge reconfiguration affects the firm's ability to sense opportunities (Eriksson, Reference Eriksson2014). In the following section, we further discuss the link between competitive information sources and dynamic capabilities while formulating hypotheses.

Hypotheses development

Web-based information is characterized by ease of use, relevance, accessibility, and reduced cost (Markovich et al., Reference Markovich, Efrat, Raban and Souchon2019). Ungureanu (Reference Ungureanu2021) emphasized the significant contribution of web-based sources to information collection activities and noted that incomplete and fragmented information retrieved from the web can be complemented by analyzing additional sources of information. Human and web-based information sources are synergistic approaches which can generate new understandings when combined (Hribar, Podbregar, & Ivanuša, Reference Hribar, Podbregar and Ivanuša2014). Fleisher (Reference Fleisher2008) explained that analysts integrate information from the web with other information sources, particularly human sources, to understand the diversity of viewpoints on important issues and generate insights. Fuld (Reference Fuld2010) noted the complementarity of web-based and human sources of information. For example, information posted on social networks about an employee's dismissal by a rival firm could indicate changes in the organization's structure or business difficulties. Therefore, an intelligence expert may attempt to confirm or test the reliability of this information through human sources (Fuld, Reference Fuld2010). We seek empirical support for these assertions in our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: There is a positive correlation between web-based and human information sources.

Sensing, the capability to identify and evaluate internal and external opportunities (Teece, Reference Teece2018a, Reference Teece2018b), can be achieved through embedded firm routines for scanning and exploring the firm's environment, technologies, and markets (Amit & Schoemaker, Reference Amit and Schoemaker1993; Pavlou & El Sawy, Reference Pavlou and El Sawy2011; Roberts, Campbell, & Vijayasarathy, Reference Roberts, Campbell and Vijayasarathy2016; Tallott & Hilliard, Reference Tallott and Hilliard2016). Sensing includes gathering information to spot customers and understand their needs and latent demands while also predicting competitors' responses (Liu & Yang, Reference Liu and Yang2020). Teece (Reference Teece2007) indicated that sensing requires extant knowledge about customers' needs and technological development and emphasized the importance of using the filtered information and its meanings to keep management informed. In summarizing the microfoundations of sensing, Teece (Reference Teece2007) pointed out stages that are inherent components of the competitive intelligence cycle: gathering, filtering, and analyzing competitive information. According to Matarazzo, Penco, Profumo, and Quaglia (Reference Matarazzo, Penco, Profumo and Quaglia2021), sensing is the capacity to scan environment trends, especially on social media, particularly to gather relevant marketing intelligence. Matarazzo et al. (Reference Matarazzo, Penco, Profumo and Quaglia2021) emphasized the accessibility and importance of exploiting customers' and competitors' digital platforms, including extracting information from LinkedIn, Facebook, YouTube, blogs, micro-blogs (Twitter, Snapchat), and other mobile applications.

In summary, the relationship between sensing and information sources seems to be synergistic, leading to the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a: Usage of web-based information is associated with stronger sensing capabilities.

Teece (Reference Teece2007) explained that the microfoundations of sensing include various sources of information that are typically human, for example, conversations at a trade show. Firm's employees – salespeople, sales managers, and research & development experts – are human sources of information (Barnea, Reference Barnea2014; De Almeida, Lesca, & Canton, Reference De Almeida, Lesca and Canton2016; Fuld, Reference Fuld1995; Le Meunier-Fitz Hugh & & Piercy, Reference Le Meunier-Fitz Hugh and and Piercy2006; Schoemaker, Heaton, & Teece, Reference Schoemaker, Heaton and Teece2018). Examples of sensing routines performed by human information sources include firm managers meeting with peers, giving speeches, or attending presentations at relevant conferences (Biesenthal, Gudergan, & Ambrosini, Reference Biesenthal, Gudergan and Ambrosini2019). Wright and Calof (Reference Wright and Calof2006) found that 73% of firms gained information about competitors from their own employees. Schoemaker, Heaton, and Teece (Reference Schoemaker, Heaton and Teece2018) emphasized the need for wide peripheral vision and monitoring of warning signals, unrecognized threats and opportunities that may lurk around corners. The personal contacts of the firm's employees may contribute important pieces of competitive information as part of their work routines. Hence, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2b: Usage of human information sources is associated with stronger sensing capabilities.

Sensing is an essential dynamic capability to ultimately convert information sources into improved seizing. Teece (Reference Teece2007) indicated that seizing newly sensed opportunities requires a well-designed business model based on data, analysis (Schoemaker, Heaton, & Teece, Reference Schoemaker, Heaton and Teece2018), intelligence, and market research (Teece, Reference Teece2007). Once a new opportunity has been sensed, either from web-based or human sources, the firm should create a business model to define its commercialization and investment strategy and priorities. In this context, a business model is a mechanism that enables a firm to seize and implement opportunities. In defining the firm's path to market, such business models make assumptions about competitors' behaviors and embrace the identities of the market segments to be targeted. These activities necessitate intelligence on the firm's environment and market (Teece, Reference Teece2007). Investment decisions, an integral part of seizing activities, are subject to errors caused by human bias, and obtaining external data may reduce the potential for such bias (Teece, Reference Teece2007). These information-gathering activities are an integral part of building a solid business model (Liu & Yang, Reference Liu and Yang2020). In this respect, seizing is enhanced by systematic use of human and web-based sources of information. Nevertheless, the benefits of web-based and human information may not fully materialize if the firm is not able to absorb the information properly. Information can only produce new opportunities if it is adequately identified and thoroughly analyzed to determine its value and suitability (Kurtmollaiev, Pedersen, Fjuk, & Kvale, Reference Kurtmollaiev, Pedersen, Fjuk and Kvale2018). Additionally, sensing capability can help the firm recognize and interpret the best and most relevant alternatives and views available through its information sources. ‘Firms high in sensing capabilities are more alert to new market opportunities in their business ecosystem’ (Zhang & Wu, Reference Zhang and Wu2013, p. 543). This leads us to the next hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Sensing capabilities mediate the impact of web-based and human information sources on seizing capability.

Reconfiguring, the third dynamic capability, is the capability for continuous renewal and the ability to transform knowledge into new products, processes, systems, and services (Paavola & Cuthbertson, Reference Paavola and Cuthbertson2022; Tallott & Hilliard, Reference Tallott and Hilliard2016). Schilke (Reference Schilke2014) indicated that inter-organizational learning routines of knowledge transfer across organizational boundaries are important to support new product development. According to Pavlou and El Sawy (Reference Pavlou and El Sawy2011), reconfiguring requires knowledge about market trends and new technologies. They claimed that in new product development, firms should sense the environment and gather information about the market to identify new product opportunities and then pursue these opportunities during exploratory early-stage research activities. These knowledge processes include collection of web-based information as the main information source and information from human sources as a complementary source (Hribar, Podbregar, & Ivanuša, Reference Hribar, Podbregar and Ivanuša2014). Scanning the environment is an essential component of developing reconfiguring ability (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997; Zhou, Zhou, Feng, & Jiang, Reference Zhou, Zhou, Feng and Jiang2017). The development of a strong sensing capability facilitates the differentiation and analysis of trends and changes in the market using different analytical frameworks and proactive searches, creating new combinations and connections. Thus, sensing may help reconfigure a process through the use of information channels (Zhang & Wu, Reference Zhang and Wu2013). Therefore:

Hypothesis 4: Sensing capabilities mediate the impact of web-based and human information sources on reconfiguring capability.

Method

The study's context is complex due to the increasing quantity and quality of business information available to firms (Lackman, Saban, & Lanasa, Reference Lackman, Saban and Lanasa2000; Olszak, Reference Olszak2014; Rajaniemi, Reference Rajaniemi2007) and the centrality of information to dynamic capabilities. For this reason, we used a mixed-methods approach combining in-depth interviews with survey-based data. By doing so, we aimed to harness the strengths of the two methods used to achieve both depth and breadth in the analysis of the subject (Creswell & Creswell, Reference Creswell and Creswell2003). We, therefore, performed two studies: study 1 aimed at identifying the contributions of web-based and human information sources to sensing, seizing, and transforming, and the findings and propositions from this study led to the analysis of survey-based data in study 2.

Study 1

Sampling and data collection

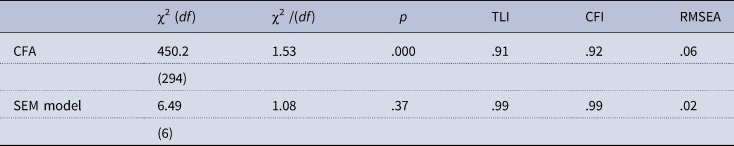

We conducted interviews with 12 executive managers from 12 firms in Israel. The interviewees were all board members: three CEOs (Chief Executive Officers), five marketing EVPs (Executive Vice Presidents), two investment EVPs, one finance EVP, and one research & development EVP (Appendix A). They were chosen based on their involvement in their firms' decision-making and therefore were expected to have a thorough understanding of the strategic planning. All firms included in the study were solely responsible for their strategic planning and were active for at least 6 years, which indicates a nonrandom survival based on accumulated resources (Coad, Frankish, Roberts, & Storey, Reference Coad, Frankish, Roberts and Storey2013). These criteria enabled depth and breadth in exploring the interactions of the information sources with the firms' dynamic capabilities. The 12 firms were purposefully chosen to represent a wide range of industry and service sectors, as firms in the same industry appear to have similar sensing practices but differ in seizing and reconfiguring (Jantunen, Ellonen, & Johansson, Reference Jantunen, Ellonen and Johansson2012). By including diverse sectors in our study, we aimed to relieve any sensing-related constraints and thus achieve a comprehensive understanding of all three dynamic capabilities.

Each interview lasted about 90 min. Nine of the interviews took place at the respective executive's office, and three were conducted over the phone. The interview guide consisted of five sections: general questions about the firm and the interviewee; competitive intelligence characteristics and processes, distinguishing between web-based and human information sources; and three sections relating to sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capabilities. The interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Data analysis

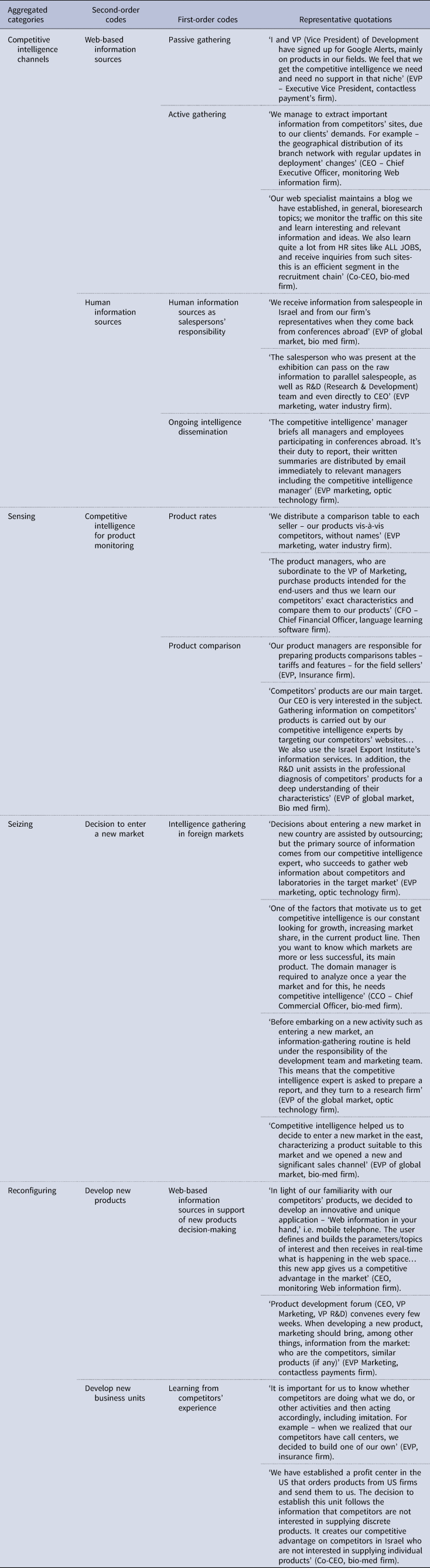

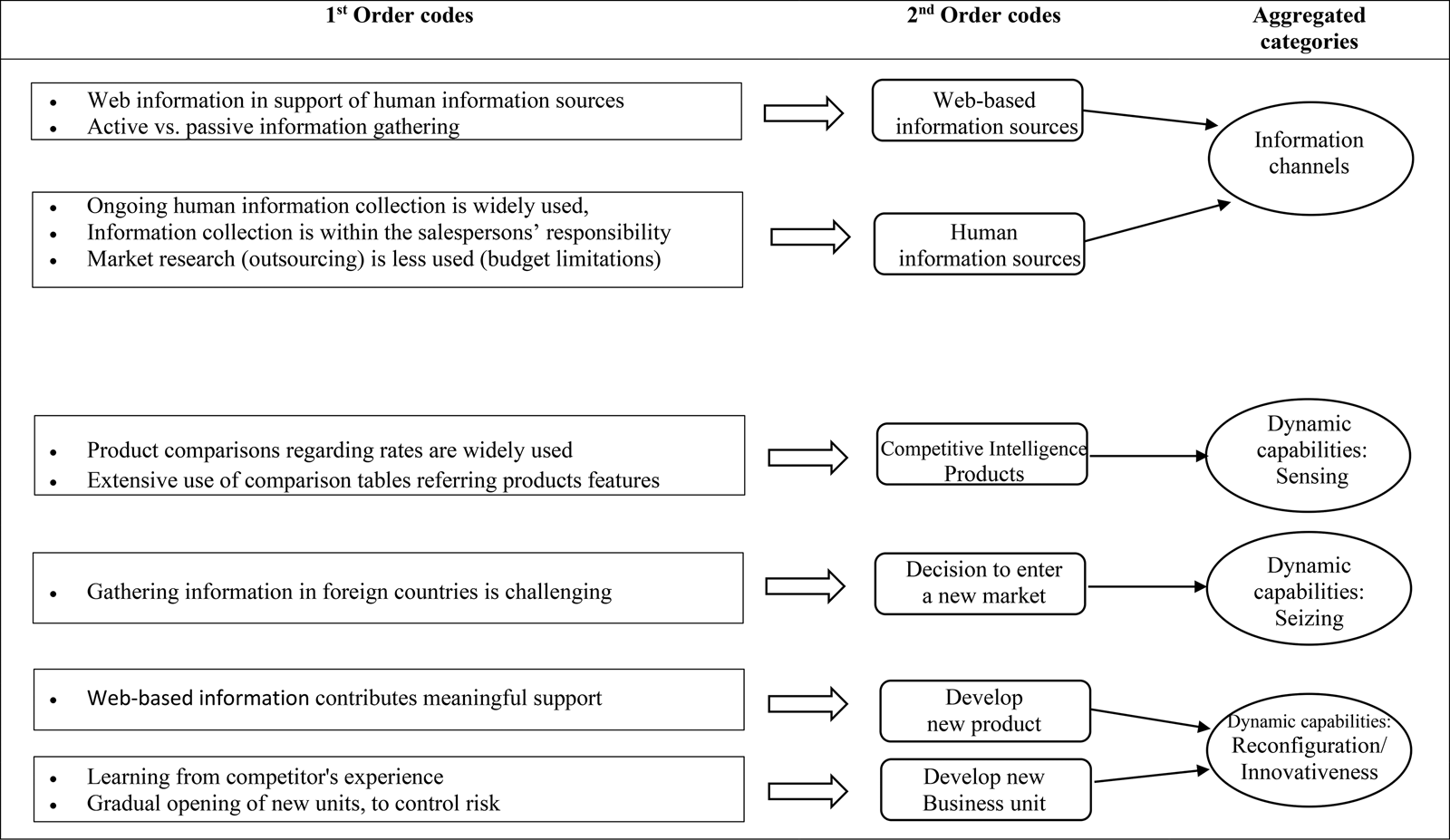

The data were analyzed in four steps following Miles and Huberman (Reference Miles and Huberman1994). In the first step, we manually open coded the raw data and extracted first-order codes from the interviews (Glaser, Reference Glaser1992; Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1990). In the second step, we re-examined the first-order codes which emerged from the open coding (i.e., intelligence gathering, ongoing intelligence dissemination, product comparison), and continued to axial coding, aggregating recurring codes and categories, and identifying relationships between the initial open codes and the newly developed, more abstract categories across the interviews (i.e., competitive intelligence for product monitoring, decision to enter new market). The third step aimed to enhance reliability by cross-checking our findings against the collected data from our interview summaries and records. In the fourth step, we ran quality checks by collecting feedback from the interviewees on our summarized findings. Finally, two of the co-authors checked the coding process against the interviewees' feedback to ensure coding and aggregated categories, that is, web-based information, human information, sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring. The findings were then written and illustrated following Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). Figure 1 illustrates the coding and categories scheme.

Figure 1. Coding and aggregated categories.

Study 2

Survey sample

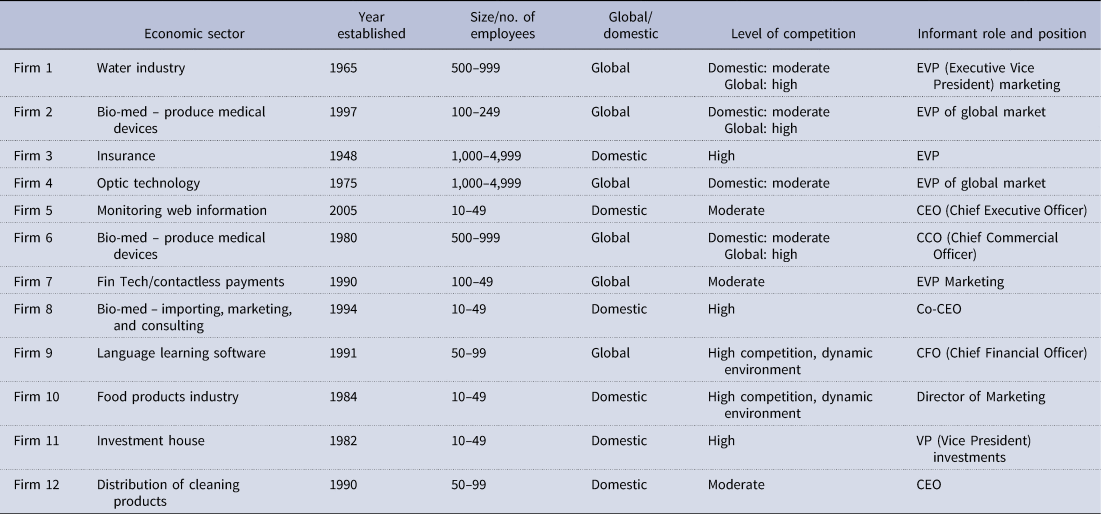

The goal in study 2 was to substantiate study 1's findings. We have cross-sectional data collected between January and February 2019, aiming to capture the essence of information sources and dynamic capabilities, which go beyond a specific industry. Several criteria were used to establish if the firm in which the manager is employed, is suitable for the study including, the industry in which it operates, level of competitive intensity in the market, and existing products or services. The web-based questionnaire was sent to 253 managers identified through social media and firm directories such as D&B's Database of Israeli firms. The questionnaire was distributed by email, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn. The Qualtrics platform was used to manage the survey. We received 164 full questionnaires (response rate = 65%). Twenty-five participants were removed from the sample because they did not meet the requirements of the sampling group; that is, they were managers from non-profit organizations, low-level managers, or managers whose job titles indicated that they were not exposed to our research topics. The final sample consisted of 139 managers.

Survey instrument and measures

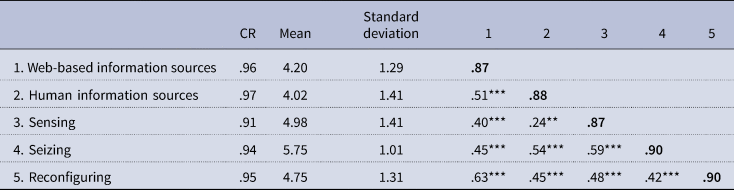

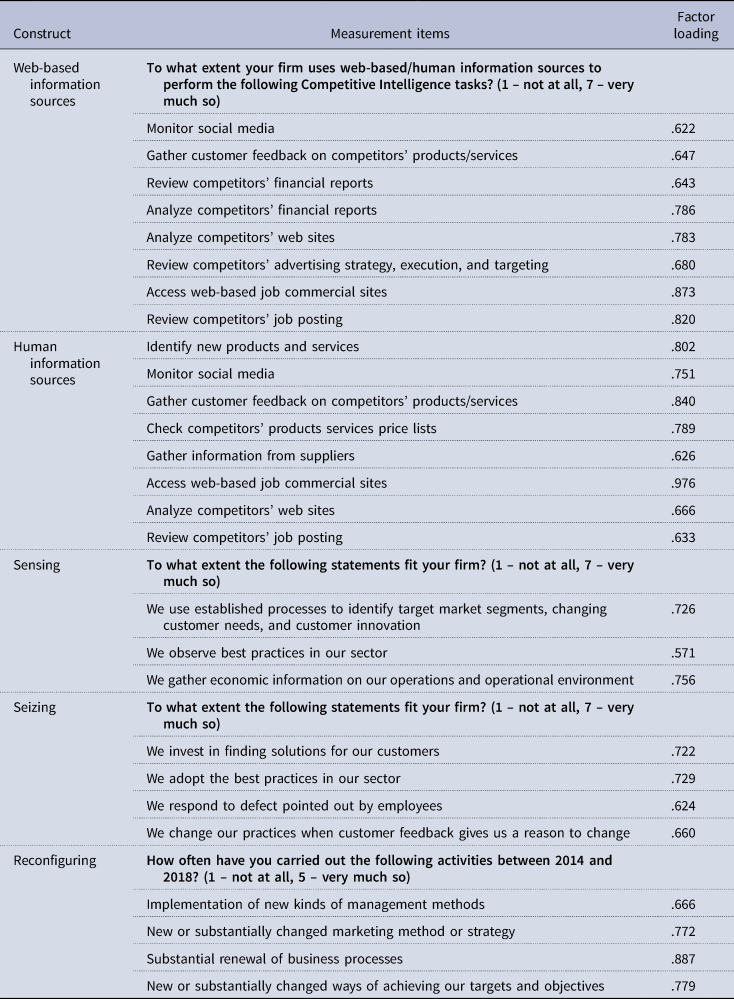

The constructs included in the questionnaire were first translated from English to Hebrew and then back-translated. The two versions were screened by a third author fluent in both languages to identify and correct any divergence in meaning. All of the measures were sourced from existing scales in the business literature and were based on a Likert scale of 1 to 7. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics, correlations, critical ratio (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) for the constructs. A full list of the items and loadings is presented in Appendix B.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

CR, critical ratio; square rooted AVEs on diagonal.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

In order to determine the relevancy of the items and scales for our study, we ran a pre-test with five managers. The outcome of this pre-test allowed for a better fit of the items used in study 2, in capturing the essence of the information aspects aimed at while eliminating irrelevant items.

Convergent validity was tested by calculating the AVE for each scale in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). The lowest AVE for the sample was .87, suggesting that, on average, the amount of variance explained by the items was higher than the unexplained variance. Discriminant validity was examined by comparing the squared AVE values to the correlations between constructs. All of the squared AVE values exceeded the correlations for each pair (see Table 1).

Web-based information was measured based on Teo and Choo (Reference Teo and Choo2001), referring to the level of use of the various information sources from the web (eight items; AVE = .76, CR = .96).

The measurement of human information source was adapted from Teo and Choo (Reference Teo and Choo2001), Fuld (Reference Fuld1995), Prescott and Bhardwaj (Reference Prescott and Bhardwaj1995), and Marin and Poulter (Reference Marin and Poulter2004) and referred to the scale of information gathered from employees exposed to competitive information in their daily operations (e.g., sales) (eight items; AVE = .78, CR = .97). These results also suggest acceptable discriminant validity and good reliability.

The measurements of sensing (three items; AVE = .76 and CR = .91), seizing (four items; AVE = .81 and CR = .94), and reconfiguring (four items; AVE = .82 and CR = .95) were all sourced from Wilden, Gudergan, Nielsen, and Lings (Reference Wilden, Gudergan, Nielsen and Lings2013). In the adaption process, one item from the sensing scale was dropped due to its low compatibility.

Finally, three control variables were included in the study: environment intensity (four items) sourced from Jaworski and Kohli (Reference Jaworski and Kohli1993), firm size (no. of employees), and firm age.

Findings

Study 1

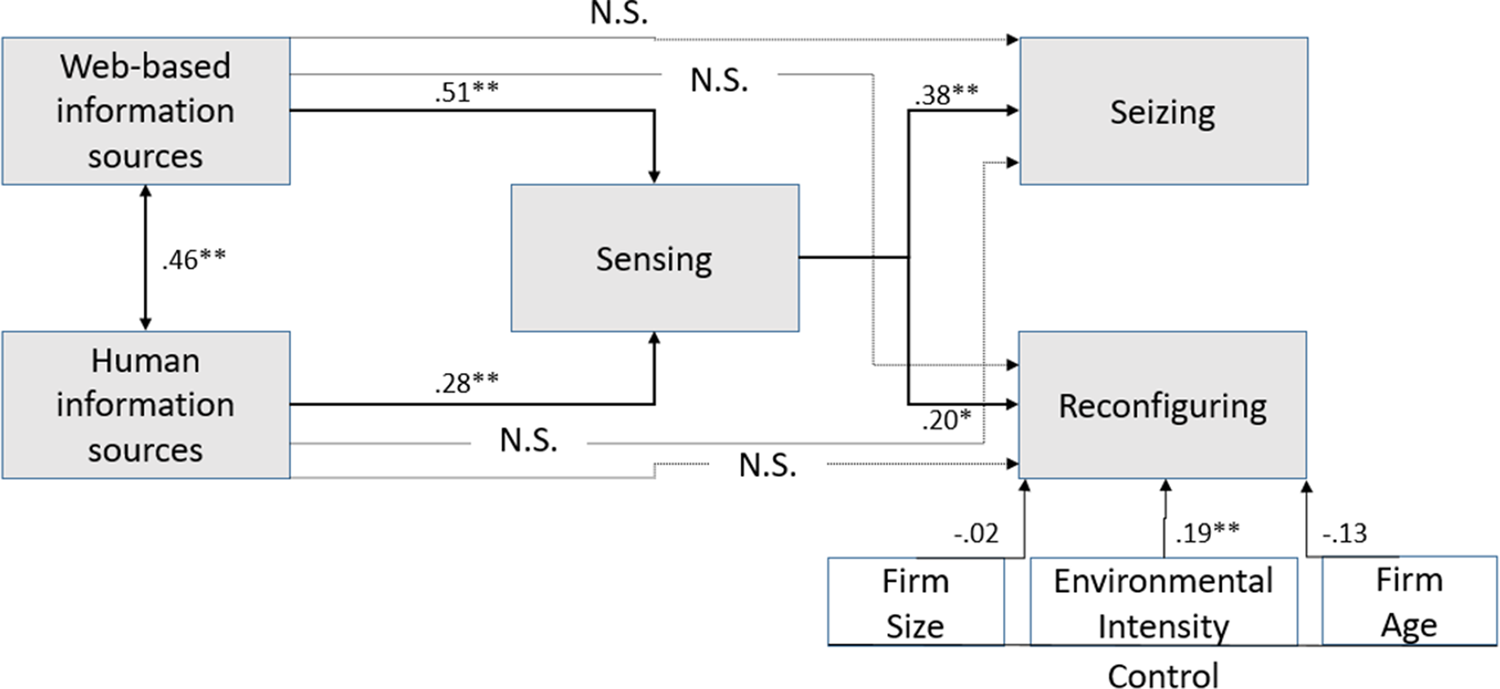

Sensing through web-based and human information sources

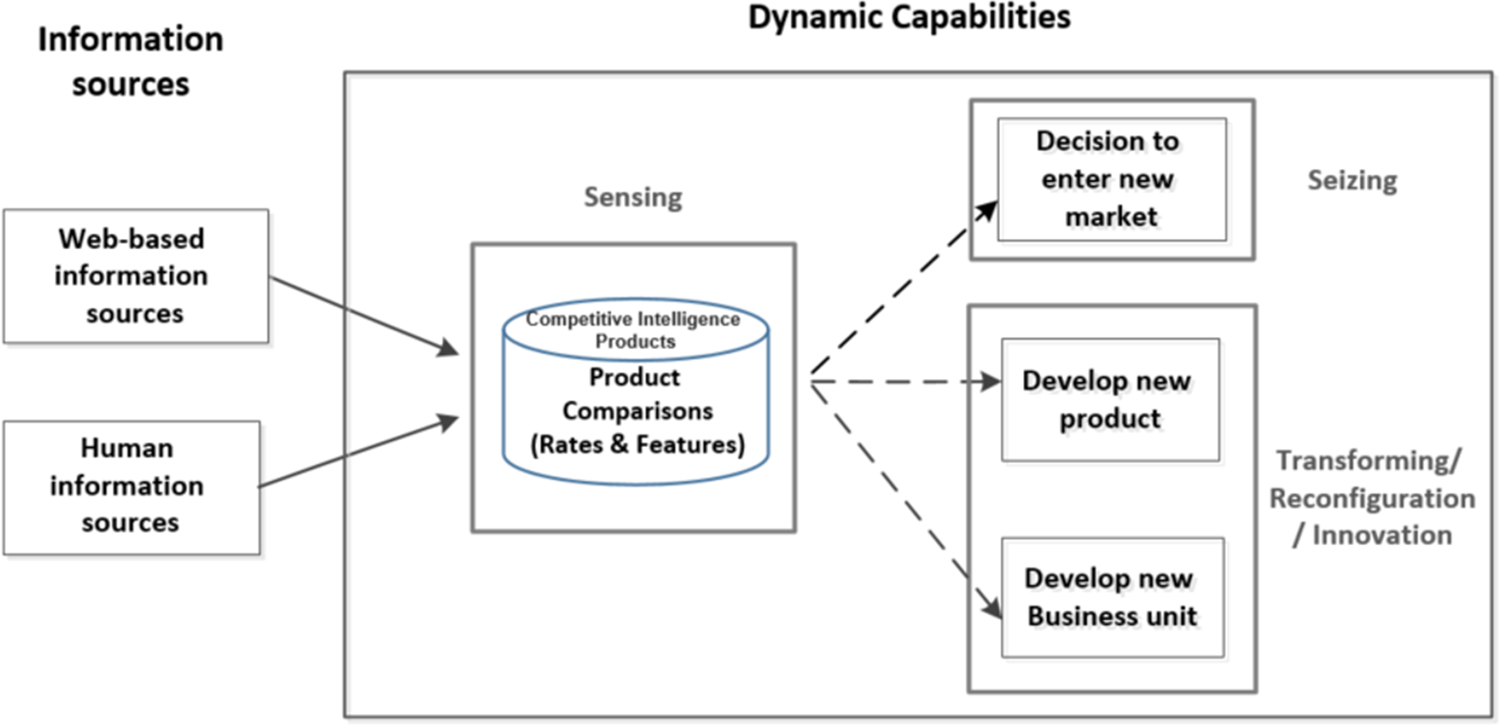

As illustrated in Figure 2, we discovered that web-based information developed alongside human information in enabling sensing capability. All firms searched and investigated competitors' websites and products involving web-based information at least to some extent alongside human information in order to find and seize opportunities and improve innovativeness.

‘Vice president of Development and I have signed up for Google Alerts, mainly on products in our fields. We feel that we get the Competitive Intelligence we need and need no support in that niche’ (Executive Vice President, contactless payment firm).

‘The Competitive Intelligence’ manager briefs all managers and employees participating in conferences abroad. It's their duty to report; their written summaries are distributed by email immediately to relevant managers including the Competitive Intelligence manager’ (Executive Vice President marketing, optic technology firm).

Figure 2. Information sources-dynamic capabilities pathway: aggregate categories.

Web-based and human information sources and the seizing capability

We found that web-based information supported the decision-making process on whether to enter a new market.

‘Decisions about entering a new market in a new country are assisted by outsourcing; but the primary source of information comes from our competitive intelligence expert, who succeeds in gathering web information about competitors and laboratories in the target market’ (Executive Vice President marketing, optic technology firm).

Human information sources were also used to support such decisions but to a lesser degree due to data-gathering barriers, such as differences in language and/or culture, geographical distance, or a small and expensive international sales force. Furthermore, purchasing reports from research firms acted as secondary move mostly aimed at completing the information gathered by internal means:

‘Strategic issues such as entering a new market will be assisted less by outsourcing and more by speaking face-to-face with the relevant people and also by our competitive intelligence expert…The large amount of free information we get from the Internet reduces the need to use research firms’ (Executive Vice President of global market, Bio-med firm).

Web-based and human information sources and the reconfiguring capability

The respondents noted two transforming activities that heavily utilize information sources: developing new products and developing a new business unit.

Developing new products draws substantially on competitive sources of information. Such information provides product comparison tables and benchmarks for prices and features. The participating firms relied primarily on web-based information, moderately on human information, and very little on market research. The respondents noted that web-based information helped them in developing new products' processes. While human information seems to provide moderate support, the market research was much less present and received low priority. Web-based information seems to fill the market research firms' diminishing place. The emphasis on products reflects that the most common output from information sources is product comparison. Firms' field levels – salespeople, resellers, and customer managers – use comparison rates and features tables. In some firms, research & development departments add important comparative information, mainly at headquarters level. In this way, the firm's field managers and headquarters are harnessed for the benefit of product development.

‘It is very important for us to be innovative, to produce new and attractive products. It brings us a competitive advantage. We mainly use information derived from financial statements: benchmarking, profit per product, profit per product unit, cancellation rates, and expenses relative to premiums’ (Executive Vice President, insurance firm).

Developing new business units is leveraged by web-based and human information sources. Decisions to establish significant new profit centers in new niches are made following benchmark information gathering on existing units in other relevant firms, or after defining service lacunas:

‘We have established a profit center in the US that orders products from US firms and sends them to us. The decision to establish this unit follows the information we gathered from the internet coupled with information from our managers and sales representative, that our competitors (also importers) are not interested in distributing (in Israel) items in small quantities. This gives us an advantage over our local competitors’ (Co-CEO, bio-med firm).

(See Appendix C for a full list of representative quotes as well as first- and second-order themes.)

In sum, study 1 revealed that usage of web-based information develops alongside traditional human sources in enabling sensing capability. Furthermore, while both information sources advance seizing capability manifested through the decision to launch a new operation, the latter is less prominent in the process. Moreover, both web-based and human sources support operations defined under reconfiguration. Finally, sensing is essential in processing the information retrieved from both sources in order to enable decisions relating to seizing and reconfiguring. Study 2 aimed to substantiate these qualitative findings.

Study 2 findings

As a preliminary stage of analysis, we conducted two checks to limit common method variance (CMV): the Harman single-factor test and the marker variable technique (Lindell & Whitney, Reference Lindell and Whitney2001). The Harman single-factor test showed that the single largest factor explained 23% of the variance (significantly lower than the threshold of 50%). In the marker variable analysis, the variable used was social desirability (theoretically unrelated). A pairwise comparison of the correlations of the two models' constructs – the unconstrained CFA (without the marker variable) and the constrained CFA (containing the marker variable) – showed no significant differences in factor loadings. The difference between the paired correlations ranged from .000 to .001, confirming the low likelihood of CMV.

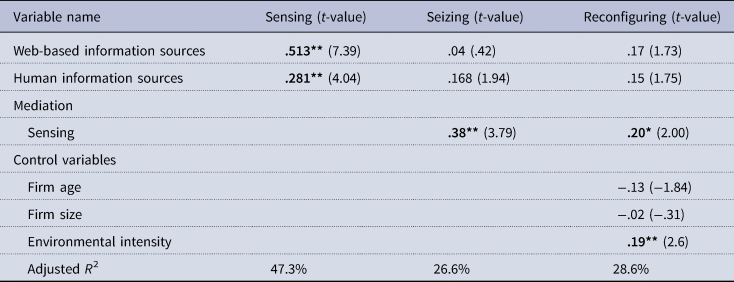

The goodness of fit of the CFA model was satisfactory (χ2(294) = 450.2, p < .000, CFI = .92, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .06). The research model was tested through structural equation analysis using the software package AMOS23, and the fit measures were satisfactory: χ2 = 6.49, df = 6, χ2/df = 1.08, p > .10, TLI = .99, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .02 (see Table 2).

Table 2. Fit measures

The results of the hypothesis testing are presented in Table 3. Figure 3 illustrates the results of the structural model. The correlation between web-based and human information sources is significant (r = .46, p < .001). Therefore, hypothesis 1 is supported. Both web-based and human sources of information are significant predictors of the level of sensing (β = .51, p < .01, and β = .28, p < .01 respectively), supporting hypotheses 2a and 2b. Hypothesis 3 proposed that sensing mediates the effects of both source types on seizing. Following MacKinnon, Fairchild, and Fritz (Reference MacKinnon, Fairchild and Fritz2007), we first checked the direct effects of the sources on seizing and on sensing (mediator) (β = .24, p < .01, β = .28, p < .01, β = .51, p < .01, β = .28, p < .01, respectively). We then ran the model with the mediator. The direct effects on seizing became non-significant, indicating full mediation and supporting hypothesis 3. Similar results were obtained for reconfiguring. The direct effects of web-based and human information on reconfiguring and on sensing were all significant (β = .27, p < .01, β = .21, p < .05, β = .51, p < .01, β = .28, p < .01). Again, once sensing was introduced into the model as a mediator, the direct effects of the sources became non-significant, supporting hypothesis 4.

Figure 3. Research model. Note: *p < .05, **p < .01.

Table 3. Structural model results – sensing mediation

*p < .05, **p < .01.

General discussion

The goal of the current research was to assess the contributions of two sources of competitive information, human and web-based, as drivers of dynamic capabilities. To that end, we integrated the relevant literature on competitive information with Teece's (Reference Teece2007) typology of dynamic capabilities, namely sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring. The ensuing hypotheses offer a framework where human and web-based information sources are essential ingredients of sensing, which, in turn, mediates their contributions to the subsequent dynamic capabilities of seizing and reconfiguring.

While the concept of dynamic capabilities has been widely researched over the last two decades (Corner & Kearins, Reference Corner and Kearins2018), including the integration between knowledge processes and dynamic capabilities (Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, Couto, Santos and Bresciani2019), little is known about how the world of information is handled and used by managers to build and enhance dynamic capabilities. Our research makes several contributions to the domains of information sources and dynamic capabilities.

The interviews with executive managers (study 1) shed light on the effects of both types of information sources in facilitating sensing and, subsequently, seizing and reconfiguring. All interviewees advocated complementarity between web-based and human information in endeavoring to monitor their ‘field of business battle.’ While this finding resembles Fleisher's (Reference Fleisher2008) outcomes and follow Bulger's (Reference Bulger2016) recommendation to use human along web-based sources of information, our findings go further in confirming that usage of web-based information does not reduce the role of human sources, but, instead increases the size of the information sources pie. This finding is strengthened by the fact that none of the firms had a dedicated competitive intelligence unit but nevertheless pronounced a strong dedication to using such means.

The findings of study 1 helped us frame the goals of study 2, which defined the scales needed to substantiate study's 1 findings. Study 2 empirically confirmed the synergy between web-based and human information sources and provided evidence of the importance of extracting competitive information from various sources as a focal driver of sensing, which in turn enhances seizing and reconfiguring. To some extent, our results echo Wright and Calof's (Reference Wright and Calof2006) findings on the importance of combining web-based and human sources of information and Gračanin, Kalac, and Jovanović's (Reference Gračanin, Kalac and Jovanović2015) findings regarding the comparable importance of these sources.

Human information collection requires managerial attention and learning, which allows for dedicated training of the sales teams to become qualified as field information gatherers (Kars-Unluoglu & Kevill, Reference Kars-Unluoglu and Kevill2021). Consequently, this traditional source of information is expensive and time-consuming to acquire (Kotler, Reference Kotler2012). Douglas and Joël Bon (Reference Douglas and Joël Bon2013) argued that salespeople who collect competitive information may generate more sales revenue and hence leverage firms' market share and profit margins. They emphasized the need for special managerial attention and training programs for achieving this. Such managerial attention should also include dedicated selection and recruitment processes to assemble a sales force with appropriate capabilities for these tasks.

Alongside human information, abundant information can be found easily and cheaply on the web. Markovich et al. (Reference Markovich, Efrat, Raban and Souchon2019) showed that the perceived quality of web-based information sources among managers was rather high. Furthermore, web-based information sources positively impacted competitive intelligence embeddedness and contributed to the decision-making process. Matarazzo et al. (Reference Matarazzo, Penco, Profumo and Quaglia2021) noted that ‘SMEs tend to be “digital followers” of bigger firms by cross-reading of web, social media and magazines’ (p. 652) in order to listen to the market and learn what is happening globally. Therefore, one might expect that efforts directed toward gathering information will shift from human to web-based sources (Teece, Reference Teece2018a, Reference Teece2018b), especially in SMEs, which are often resource-constrained (Pinho & Prange, Reference Pinho and Prange2016). Yet, our research shows that the importance of human information remains substantial alongside the extensive use and importance of web-based information.

In sum, despite the easy availability of web-based information as an alternative information source and the need to invest in training and equipping the sales force with sophisticated digital devices to improve their ability to acquire useful information, human information remains a valuable tool in advancing firms' competitiveness. The case of Novartis Pharmaceuticals (Day & Schoemaker, Reference Day and Schoemaker2016; Schoemaker, Heaton, & Teece, Reference Schoemaker, Heaton and Teece2018) provides an example of the potential of information from sales representatives as an intelligence force. At Novartis, sales representatives were equipped with devices to improve and change their conversations with their clients from monologs to dialogs, enabling management to sense weak signals and get a clearer peripheral view of the business environment.

The qualitative results of study 1 indicate that sensing is crucial in advancing seizing and reconfiguring by compiling information from various sources. Study 2 confirmed study 1 by uncovering quantitative mediating effects of sensing on the relationships of web-based and human sources of information with seizing and reconfiguring. The structure of the intelligence cycle may provide an explanation of the mediation by sensing (Nasri, Reference Nasri2011). The first stage of the cycle is planning and focus: key intelligence topics are defined, and the required resources are assessed (Ungureanu, Reference Ungureanu2021). This stage, which initiates the collection and analysis of information, can be attributed to the sensing ability. A firm that does not focus its intelligence efforts in the right strategic directions will reduce the power of information sources to improve the utilization of opportunities and the reconfiguration of the company (Markovich et al., Reference Markovich, Efrat, Raban and Souchon2019). Thus, our research emphasizes the essential role of utilizing information in the process of sensing, which evolves into enhanced seizing and reconfiguring. In doing so, this paper advances on Teece's (Reference Teece2007, Reference Teece2018a, Reference Teece2018b) theoretical claims of dynamic capabilities inter-relationships. The processes of successful seizing and reconfiguring vary in time and scope but share a common denominator in the form of relevant and accurate impact of information sources, and enhanced sensing will reveal more opportunities as input (Pavlou & El Sawy, Reference Pavlou and El Sawy2011). Given the potential for information overload, sensing capabilities are invaluable for both screening out irrelevant information and focusing on essential information. Failing to respond to the threats exposed by sensing capability may be fatal to the firm, as in the case of Kodak (Schoemaker, Heaton, & Teece, Reference Schoemaker, Heaton and Teece2018). Superior sensing capability is important for efficiently mediating seizing and reconfiguration and by exposing more information about the business environment (Torres, Sidorova, & Jones, Reference Torres, Sidorova and Jones2018).

Conclusion and implications

Limitation and direction for future research

Our research has several limitations that offer opportunities for future research. First, the sample included managers from firms in various industries and fields of expertise. While this allowed us to extract valuable data via diverse insights, finer resolution of the effects could be obtained by comparing service versus manufacturing firms or local versus international firms. Second, our sample was collected in a single country, Israel. Due to the spillover of intelligence processes from the military to civilian arenas (Crosston & Valli, Reference Crosston and Valli2017), we expect that Israel provides a rich context for our study. However, we encourage quantitative studies from developing and developed countries to validate the findings. Finally, our research results relate to a certain point in time, but dynamic capabilities are not developed instantaneously. Hence, we recommend longitudinal research that explores the temporalities relevant to the development of each dynamic capability. Such research will enhance the understanding of the relationships of the growth of dynamic capabilities with the nature and extent of dynamic capabilities interplay.

Theoretical implications

This research addresses a gap in the literature by empirically exploring the potential role of competitive intelligence in dynamic capabilities development in light of the considerable advances in and diffusion of online platforms and technologies. We highlighted how firms may achieve dynamic capabilities by applying competitive information channels: web-based alongside human sources. We demonstrated that the use of these sources enhances all dynamic capabilities types – sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring. We further confirmed the mediating effect of sensing. Specifically, we found that both web-based and human competitive information facilitate sensing, which in turn mediates the effects of these information sources on both seizing and reconfiguring.

Our study provides two main theoretical contributions. First, while existing knowledge already confirmed the centrality of external information for building dynamic capabilities (Torres, Sidorova, & Jones, Reference Torres, Sidorova and Jones2018), most research has concentrated on the information retrieved and neglected its source. Our findings advance existing work distinguishing between two well-known information sources, web-based and human, and illustrate their idiosyncratic influences on dynamic capabilities. As mentioned earlier, the competitive intelligence cycle, which includes planning, information gathering, and analyzing, is vital to the strategic stages of defining objectives, analysis, and strategy formulation. The centrality of information sources to this process is evident in defining the forces that make up the current firm's competitive environment (e.g., competitors, customers, and other stakeholders). Hence, the combined effect of the web-based and human sources allows decision makers to better understand the business environment.

Second, unlike previous studies that explored individual dynamic capabilities (Bingham, Heimeriks, Schijven, & Gates, Reference Bingham, Heimeriks, Schijven and Gates2015), our research provides insights into the links among dynamic capabilities. Previous studies found no direct impact of sensing on performance (Markovich, Efrat, & Raban, Reference Markovich, Efrat and Raban2021), but we conclude that the true value of sensing is its mediation of the effect of information sources on seizing and reconfiguring, both of which have been shown to enhance firms' performance (Wilden et al., Reference Wilden, Gudergan, Nielsen and Lings2013). In this respect, we advance on Bingham et al., (Reference Bingham, Heimeriks, Schijven and Gates2015) in explaining the development of all three types of dynamic capabilities in parallel, based on sensing.

Practical implications

It can be assumed that greater emphasis on competitive intelligence will contribute to better strategic decision-making processes and enhanced dynamic capabilities. Such an increase in attention can be achieved by raising the organizational level of competitive intelligence ownership in the firm. Higher positioning of competitive intelligence will increase managerial awareness and through it, the use of competitive information in dynamic capabilities development and decision-making (Durán & Aguado, Reference Durán and Aguado2022). This will enhance the achievement of strategic goals and growth engines. An important observation arising from our qualitative research findings is that while the managers valued information sources in support of their strategic decision-making processes, none of the firms had a dedicated competitive intelligence unit. Indeed, in all firms, marketing personnel were responsible for human and web-based intelligence.

When available, the intelligence unit usually provides a thorough analysis of the current business environment. This includes early warnings to assess new threats in hidden corners (Schoemaker, Heaton, & Teece, Reference Schoemaker, Heaton and Teece2018), intelligence about competitor's responding and adjusting to the strategy's initial and advanced implementation phases. An intelligence unit should draw an updated picture of the business environment – customers, suppliers, regulation authorities, etc. (Cavallo, Sanasi, Ghezzi, & Rangone, Reference Cavallo, Sanasi, Ghezzi and Rangone2020; Herring, Reference Herring1992). Elite intelligence units provide predictive intelligence reports – a forecast of the competitive environment that the firm is likely to encounter. To conclude, in order to leverage the added value of the information in the organization, it is suggested that the intelligence experts will have an autonomous unit, distinguished by a separate mission, and that they will be informed of the strategic planning in advance.

Appendix A: Key firms characteristics

Appendix B: Constructs, measurement items, and factor loadings

Appendix C: Data supporting interpretations of competitive intelligence processes