I. Introduction

This paper examines the potential legal, social, and ethical implications associated with implementing active voluntary registries as a community-oriented solution for increased interaction between law enforcement and individuals with dementia. We explore the particular importance of implementing proactive strategies in communities experiencing the highest growth in the dementia population, such as Phoenix, Arizona. It argues that while potential barriers to implementation should be considered, voluntary registries may offer communities a cost efficient and effective approach to address this growing interaction in communities across the country, particularly in regions experiencing significant growth in the dementia population and initiatives to support aging-in-place.

Section II discusses the growing number of individuals nationally and worldwide diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease and the associated economic and social costs to caregivers and society. Section II provides a backdrop for recognizing the growing public health crisis associated with dementia in the City of Phoenix and reviews some of the strategies Phoenix used to address the crisis. Section III looks at the increased interaction between law enforcement and individuals with dementia within the context of search and rescue efforts and discusses proactive measures across the country to protect individuals with dementia when they go missing. Section IV provides an overview of the role and function of voluntary registries in protecting this vulnerable population and includes comparative tables illustrating registries in place across the United States (US) and the state of Arizona. Section V focuses on the potential barriers to the enactment of voluntary registries through a legal analysis of HIPAA, state privacy statutes, and privacy and liability considerations. The paper concludes with section VI, which argues that notwithstanding potential legal and ethical concerns, voluntary registries may offer communities a cost efficient and effective approach to address this growing interaction in communities across the country, particularly in regions experiencing significant growth in the dementia population and with initiatives to support aging-in-place.

II: Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia Related Diseases: A Growing Public Health Crisis

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) estimates that there are approximately 50 million people living with dementia globally, and that an additional 10 million individuals will be diagnosed with this brain disease each and every year. 1 Within the US, the Alzheimer’s Association (2021) estimates that 6.2 million people are living with Alzheimer’s or some other form of dementia. 2 With the greatest risk factor for dementia being ageReference Herbert, Bienias, Aggarwal, Wilson, Bennett, Shah and Evans 3 , Freedman et al (2018) have suggested that this number will markedly increase due to the country’s shifting demographics.Reference Freedman, Kasper, Spillman and Plassman 4 Alzheimer’s Disease was recognized nationally as a major public health issue in 2012.Reference Blank 5 Since then, federal councils and agencies have been tasked with creating coordinated action plans to address the growing crisis and at least 43 states have developed plans targeted to increase awareness, improve data collection, increase research funding, improve public safety for those with Alzheimer’s Disease, and improve and develop policies to help this population and their families. 6

The economic burden of dementia is significant, with Alzheimer’s Disease considered the most expensive disease in the United States. Within the US, 2021 estimates suggest that the cost of paid care for individuals living with Alzheimer’s Disease and other cognitive impairments is US $355 billion per year. This figure does not account for unpaid care provided by family members and other caregivers, which has been estimated at US $256 billion annually.

The economic burden of dementia is significant, with Alzheimer’s Disease considered the most expensive disease in the United States. 7 Within the US, 2021 estimates suggest that the cost of paid care for individuals living with Alzheimer’s Disease and other cognitive impairments is US $355 billion per year. 8 This figure does not account for unpaid care provided by family members and other caregivers, which has been estimated at US $256 billion annually. 9

While these numbers are staggering, they pale in comparison against the physical, mental and social costs borne by families, caregivers, and local communities. Only 15% of individuals with dementia live in a nursing home setting, with the majority of those affected living at home or in other community settings.Reference Mather and Scommegna 10 Estimates suggest that this burden of care falls on approximately 16 million caregivers in the US, who collectively provide 18.6 billion hours of unpaid assistance annually. 11 Caregiving for individuals with dementia is time intensive, with daughters disproportionately providing the bulk of the unpaid care.Reference Kasper, Freedman, Spillman and Wolff 12 Foregone wages and the impact of providing care can also have long term implications on the caregiver’s wellbeing.Reference Coe, Skira and Larson 13 Studies suggest that those caring for an individual with dementia often feel stressed, overburdened, isolatedReference Brodaty and Donkin 14 , and exhibit a higher prevalence of depression.Reference Ma, Dorstyn, Ward and Prentice 15 In addition, there is a physical toll to caregiving, with Brodaty and Donkin (2009) noting that “caregivers report a greater number of physical health problems and worse overall health compared to non-caregiver controls.” 16 Caregivers across the country face growing challenges as they struggle to cope with the increasing financial cost and emotional stress associated with caring for dementia patients. These stresses are particularly burdensome for individuals living in states with rapidly increasing dementia populations, as systems and supports are not keeping up with this growing public health crisis.

In 2020 the State of Arizona was home to approximately 150,000 individuals living with dementia. 17 Consistent with US figures, the majority of care in Arizona is provided by family and friends. 18 With an increasing number of adults aged 65 years and older in the state, the number of people living with dementia in Arizona is expected to grow to 200,000 by 2025, representing the highest projected growth rate in the United States. 19 While this sharp increase will place a significant burden on the state’s health system and related services, much of the burden will be borne by caregivers and the local communities in which these individuals reside. The Arizona Alzheimer’s Task Force recognizes the need for collective action across agencies and stakeholders, in order to not only cater for the increase in individuals with dementia, but also to support the caregivers and family members. As articulated in the Task Force’s Framework for Action, this includes creating a “Dementia-Capable System” in the state. 20

In recognition of the growing public health crisis associated with dementia, the City of Phoenix (“Phoenix”), the fifth largest city in the US and home to nearly one quarter of Arizona’s population, committed itself to becoming a “dementia-friendly city.”Reference Ventar 21 In early 2020, Phoenix was named a member of Dementia Friendly America, and became the largest city in the US to achieve this status.Reference Burkhart 22 As articulated by Mayor Kate Gallego in her 2019 State of the City address, one central component of the initiative is specialized training for members of the Phoenix Fire Department who are often first on the scene when issues arise with individuals suffering from dementia in the community.Reference Gallego 23 Members of the Phoenix Police Department already undergo Mental Health First Aid training, a curriculum focused on acute psychiatric emergencies and substance abuse which includes content related to dementia, though dementia is not a central component of the training.

In addition to mental health first aid and dementia training, Phoenix has implemented multiple additional strategies to address the acute needs of people with dementia who access the public safety system. When a person living with dementia or their caregiver calls for 9-1-1 assistance, dispatchers patch the caller through to the county crisis line to provide someone to talk while emergency responders (including police or mobile crisis teams) are en route. In addition, police officers responding to calls for behavioral health issues, including dementia, can author a report and referral to a crisis team or community navigator from a partner agency for follow-up. The Phoenix Police Department includes dementia in its behavioral health strategy, and notes that people living with dementia are frequently included in referrals to community navigator programs. 24

More recently Phoenix began to explore the possibility of a voluntary registry of individuals suffering from dementia as a pillar of their “dementia-friendly” agenda. As currently framed in the City’s discussions, such a registry would expedite missing persons investigations for people with dementia and potentially improve the likelihood of safe return of the missing person to caregivers. This would reduce the resource burden on an already-strained public safety system and personnel. While such voluntary registries for a variety of behavioral health indicators are not new in the US, nor in the State of Arizona, they do raise a number of questions that need to be addressed prior to implementation.

III. Increased Interaction Between Law Enforcement and Individuals with Dementia

The ever-increasing number of individuals living with dementia at home with family and friends raises questions about the need for innovative approaches to proactively address this growing public safety issue. According to the Alzheimer’s Association 60% of individuals living with dementia will have trouble returning to their home from an outing at some point in time. 25 Anyone experiencing memory problems is at risk of wandering. 26 The term “wandering” is used to describe a set of behaviors such as repetitive pacing, excessive walking, and hyperactivity.Reference Rowe, Vandeveer, Greenblum, List, Fernandez, Mixson and Ahn 27 Persons with dementia may experience wandering, along with cognitive impairment and loss of short-term memory, increasing the likelihood that they may become disoriented and possibly lost. 28 Common dementia-associated behaviors such as memory loss, confusion, and wandering, tend to increase as an individual’s disease progresses. Not knowing when or if an individual with dementia might wander is a major cause for caregiver stress and burnout and further contributes to this growing public safety problem. 29

Wandering from home is among the most common emergency situations that requires police intervention affecting individuals with dementia.Reference Sun, Gao, Brown and Winfree 30 A delay in search and rescue efforts can mean the difference between life and death for the missing person. Experts estimate that up to 61 percent of individuals with dementia who wander and become lost, will suffer significant injury or death if not located within 24 hours.Reference PRWeb 31 Many who wander are found within 1.5 miles of where they were last seen 32 making proactive caregiver planning and search and rescue efforts essential to successfully locating missing individuals.

The 2011 Rowe et al. study reviewed 325 missing person incident reports that required calls to law enforcement involving individuals with dementia. 33 In the majority of cases, the person who went missing was intentionally unsupervised while conducting a normal and expected activity. This lack of supervision suggests that the individual did not likely have a prior history of wandering. The findings reported by Rowe et al. suggest that quickly and efficiently finding individuals who go missing is critical to avoid adverse outcomes.

Table 1 shows the number of missing individuals found dead vs. found alive in the 2011 Rowe et. al. study. Notably, it took significantly more time to locate those who died than those who were found alive. Ninety percent (n=195) of the individuals who were found alive were located within two days after they were reported missing. Of those who were found dead the two main causes of death were death by exposure (n=57) and drowning (n=37). The third cause of death was motor vehicle accidents, where the missing individual was either a driver or a pedestrian (n=3). Age and gender were not significant factors in who was dead vs. alive. The study did not address who located the missing individuals, though it is likely law enforcement personnel played a major role in search and rescue efforts as law enforcement assistance was sought in each case.

Table 1 Timing is critical when responding to search and rescue calls. Rowe et al. study summary33

In response to the growing dementia population and the recognition that timing is critical when responding to search and rescue calls, many law enforcement agencies have implemented a variety of tools and practices to assist first responders in locating missing individuals with dementia. These strategies range from public alert systems to passive identification techniques and active locator techniques. “Silver Alerts” are a form of public alerts that exist in every state in the US that help alert the community when a person who wanders is driving a vehicle. Passive identification programs display an individual’s health and identification information on items that may be kept on their person at all times, such as bracelets, identification cards, and tagged clothing. Active locator technology programs use wireless technology such as radiofrequency to help locate missing individuals and tracking technology uses satellite and cellular signals similar to GPS car systems.

As the Rowe et. al. 2011 study indicates, and Table 1 illustrates, research suggests that in order to reduce negative outcomes when individuals with dementia go missing, communities must expand and build upon current initiatives and implement preventive evidence-based strategies that aid law enforcement efforts to quickly locate missing persons with dementia, and respond to their needs in an appropriate manner. 34 Search and rescue efforts place a great burden on police departments’ financial and personnel resources, costing departments an average of US $13,500 per search and rescue effort. 35 Timing is critical when it comes to avoiding adverse outcomes when individuals with dementia go missing. Rather than wait for a person to exhibit wandering behavior as a prompt for preventative action, caregivers and the community should work together to take proactive measures to protect this vulnerable population. Active voluntary registries have been introduced as one effective strategy to assist law enforcement in quickly and cost effectively locating missing individuals.

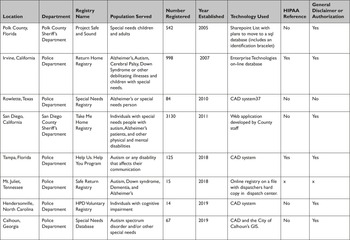

IV. Comparative Tables: Law Enforcement Agencies & Municipalities Using Voluntary Dementia Registries

To date, voluntary registries have been implemented in multiple US communities with varying success. Many of these registries serve vulnerable populations and include individuals with cognitive disabilities such as Cerebral Palsy, Down Syndrome, Autism, Alzheimer’s, and other physical and mental impairments. Police and sheriff departments across the country have implemented registries in an attempt to introduce policies and systems that support law enforcement in their search and rescue efforts when a vulnerable individual goes missing. Table 2 illustrates examples of law enforcement and municipal agencies across the country that have implemented voluntary registries to address missing incidents involving individuals with cognitive disabilities. Voluntary registry systems provide law enforcement with important information about registered individuals including a physical description of the registrant, significant locations, medical information, and information about cognitive or communication impairments that can greatly assist first responders to quickly and safely locate missing persons with dementia during emergency calls.

Table 2 Voluntary Registries throughout the United States

*Polk County data collected March 2021 all other data collected April/May 2020

As illustrated in Table 2, one of the first US voluntary dementia registries for public safety was established in Polk County, Florida in 2005 with the program officially launching in 2007. 36 Voluntary registries continue to grow in popularity as law enforcement and communities recognize the lifesaving and cost saving benefits associated with implementation. Registries use varying technology to house registered individuals’ data; some use paper forms, online forms or a combination of both to proactively plan for an emergency situation. When a registered individual goes missing, first responders can immediately access an individual’s identifying information via the voluntary registry, minimizing the duration of the search and limiting risk to both the individual and the community.

Individuals diagnosed with dementia who wander may attempt to return to a place from their past such as a former home, favorite place in the community, or former place of employment. Providing individuals diagnosed with dementia or other cognitive impairments the option to voluntarily register before a missing incident or other emergency occurs, provides law enforcement with vital information; such as an individual’s identifying information, frequently visited locations, and locations from their past. Active voluntary registries can include this type of information as well as other relevant information that might assist law enforcement responding to a search and rescue call. Having access to this information in advance allows law enforcement to quickly and efficiently respond to calls for assistance by greatly reducing the amount of time required to interview caregivers and investigate leads before commencing an active search.

While it is encouraging to see large cities like Phoenix adopt solutions to address increased interaction between law enforcement and individuals with dementia, more needs to be done. The City of Phoenix is home to many elderly citizens and is considered a popular retiree community worldwide. According to the World Population Review, using the US Census 2018 ACS 5-Year Survey, there will be approximately 1,206,740 adults, 173,258 of whom are considered seniors, living in the City of Phoenix in 2021. 38 States with large retiree populations and rapidly growing aging populations, will particularly benefit from innovative and targeted solutions that support first responders and law enforcement in quickly and efficiently locating missing persons with dementia. Phoenix has recognized the importance of community-oriented solutions in addressing its growing dementia population, though the fifth largest city in the country has not yet implemented a voluntary registry system. Current solutions include a first responder Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) that collaborates with behavioral health partners to provide appropriate crisis services and to assist individuals with mental illness. 39 Additionally, current Phoenix policing practices include a Mental Health First Aid training (an eight-hour course) for all police officers. The course does not currently include dementia training, though there are discussions around expanding the training to include a dementia focused course. There currently is not a policing code specific for dementia in Phoenix. Rather, the Phoenix Police Department uses general welfare codes in responding to calls related to people with dementia. The Phoenix Fire Department also responds to calls related to people with dementia, through the fire department and its Crisis Response Unit does not generally engage in missing persons operations.

The Sun, Gao et al. (2019) study which focused on evaluating and understanding police competence in handling Alzheimer cases and surveyed two police departments located in central Phoenix.Reference Sun, Gao, Brown and Winfree 40 Police officers reported that they encountered challenges when responding to calls involving individuals with dementia, in part because the individual had difficulty with recalling information and communicating with police. Police subjects reported that there were no separate standard policing search protocols or procedures when engaging with the dementia population, reporting that they instead followed the same protocols used in search and rescue emergencies for missing children. 41 The study’s findings suggest that law enforcement departments would greatly benefit from training focused on recognizing the signs of dementia and on improving communication skills. Improving police officer competency when responding to emergencies involving individuals with dementia through education and the implementation of proactive policy, systems, and procedures, such as an active voluntary registry system, will help law enforcement agencies as well as the entire community keep vulnerable populations safe while meeting this growing societal challenge. 43

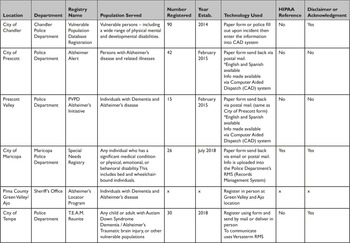

Table 3 illustrates voluntary registries that have been implemented throughout the state of Arizona. Registries have been implemented in rural areas of the state, such as Prescott and Prescott Valley, as well as in more populated suburban communities such as Tempe and Chandler. Agencies and municipalities throughout the state of Arizona that have implemented voluntary registries can provide a blueprint for registry creation and implementation for the City of Phoenix.

Active voluntary registries encourage collaborative proactive planning by caregivers and law enforcement. Registries facilitate rapid and efficient responses to search and rescue calls by providing emergency dispatchers and law enforcement access to critical data. Frequent barriers to registry implementation and uptake include concerns about privacy and protecting individual health information. In many cases, departments reference the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) as a barrier to, or consideration of, enacting voluntary dementia registries for public safety.

Table 3 Voluntary Registries in Arizona

*Data collected May 2020

V. Legal Implications Posed by Voluntary Registries: A Look at HIPAA, State Privacy Statutes, Privacy & Liability Considerations

Voluntary registries, especially those that compile information on individuals with health conditions, raise a number of legal and ethical issues. This section focuses on the key concerns and potential barriers to implementation, and argues that the benefits voluntary registries offer as a community-oriented solution to protecting vulnerable populations, such as individuals with dementia, outweigh potential ethical, privacy, or liability concerns.

A. HIPAA Overview

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) is a federal law that creates national standards that protect individuals’ sensitive health information from disclosure without their authorization and consent. 44 HIPAA was enacted, in large part, to provide patients with confidence that their private healthcare information would remain confidential in order to allow for and encourage the free flow of medical information in response to the need to “improve the portability and accountability of health insurance coverage” for employees between jobs.Reference McKinstry 45 HIPAA’s other objectives include preventing “waste, fraud, and abuse in health insurance and health care delivery, to promote the use of medical savings accounts, to improve access to long-term care services and coverage, to simplify the administration of health insurance, and for other purposes.” 46

Pursuant to the Act, in December 2000, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) issued The Privacy Rule, 47 (45 CFR Part 160 and Subparts A and E of Part 164) also known as the “Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information,” regulating who has access to Protected Health Information (PHI) and under what circumstances private health information may be shared and used. 48 The Privacy Rule became effective on April 14, 2001 and was the first comprehensive Federal law regulating private health information. 49 The HIPAA Privacy Rule delineates specific “covered entities” that are subject to the Rule. Contrary to popular belief, HIPAA does not apply to all entities that hold sensitive health related information. The Privacy Rule outlines the permitted use and disclosure of health-related information by these covered entities and delineates which entities must comply with HIPAA. 50

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services lists the covered entities and individuals subject to the Privacy Rule on their website 51 :

-

i. healthcare providers such as hospitals and doctors;

-

ii. health plans including health insurance plans and government plans like Medicare;

-

iii. healthcare clearinghouses, which are private or public entities that serve as intermediaries and perform functions such as data analysis and billing for a covered entity; and;

-

iv. business associates of HIPAA covered entities, such as the individuals and entities listed above, that provide services such as data processors, collection agencies, accounting services, inter alia. 52

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has regulatory authority over HIPPA compliance for covered entities and their business associates. 53 HIPAA is enforced by state attorney generals and failure to comply with HIPAA can result in both civil and criminal penalties for covered entities. Criminal sentences for violations can include up to ten years in prison and fines up to $US250,000.Reference Lawson, Orr and Klar 54 Civil money penalties for HIPAA violations have been awarded up to $US4.8 million.Reference Tomes and McCart 55 HIPAA does permit the disclosure of certain protected information without patient authorization by covered entities for specified uses in the public interest such as in judicial proceedings, to avert threats to public safety, and for research and public health. 56

B. HIPAA as Applied to Voluntary Registries

Most municipal and law enforcement agencies are not covered entities under Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 45 Sections 164.104, 164.502, and therefore are not subject to HIPAA’s Privacy Rule.Reference Kirtley and Shalley-Jensen 57 As a non-covered entity, law enforcement agencies will not be sanctioned for non-compliance under the Privacy Rule, and consequently, municipalities and law enforcement agencies that implement voluntary registries do not need to concern themselves with the threat of potential HIPAA liability. Nevertheless, as illustrated by Tables 2 and 3, some law enforcement agencies with voluntary registries reference HIPAA on their websites and in their registry forms. For example, Irvine’s Return Home Registry, Tampa’s Help Us. Help You. Registry, and the City of Maricopa’s Special Needs Registry all reference the HIPAA Privacy Rule, with Tampa’s registry form 58 even requiring the registrant to waive any HIPAA claims before placement on the registry.

The misconception that all law enforcement agencies and municipalities are subject to HIPAA has the potential to adversely impact the establishment, implementation, and success of voluntary registries for individuals with dementia and other health conditions. This misconception has the potential to deter agencies from exploring voluntary registries as a tool to assist law enforcement, and may also deter individuals adverse to signing potential HIPAA waivers from registering. Requiring individuals to waive potential HIPAA claims in order to participate in a voluntary registry serves no purpose since these registry programs are not captured by HIPAA and the legislation does not apply to these agencies. Such waivers may unnecessarily discourage vulnerable individuals or their caretakers from registering because they do not wish to preemptively waive legal recourse for the agency’s potential violation of (nonapplicable) HIPAA privacy rights. Agencies looking to create active voluntary registries to help mitigate negative interactions between law enforcement and individuals with dementia and other special needs, may be dissuaded from their efforts due to the mistaken belief that they must implement new security measures and protocols to safeguard health data, and that implementing registries could expose their agencies to potential HIPAA violation claims and subsequent penalties.

Law enforcement agencies considering implementation of registry systems need not look to HIPAA for legal guidance. Agencies should instead review relevant state and local privacy statutes to ensure their registries comply with existing applicable law.Reference Kirtley and Shalley-Jensen 59

C. State Health Privacy Statutes as Applied to Voluntary Registries

Since HIPAA and other Federal laws do not apply to all entities that may have access to private health information, agencies considering voluntary registries should review their state’s privacy and confidentiality statutes. This discussion focuses on state statutes and does not review all applicable state law, which includes local regulations and common law. State agencies should consider all legal protections afforded by state law, in order to ensure compliance when developing voluntary registries for dementia.

The level of protection states afford individuals’ private information varies state to state. Some states have no additional relevant privacy laws or they may have statutes that are identical in substance to HIPAA, 60 and generally HIPAA preempts state law that conflicts with the federal law.Reference Pritts, Choy, Emmart and Hustead 61 States may implement statutes that offer more privacy protection than HIPAA and that cover additional individuals and/or entities that hold private health information. In those instances, law enforcement agencies and municipalities should consider what agencies are defined in the statute and what kind of information is protected when evaluating applicability to their departments and to registry databases.Reference Pritts, Choy, Emmart and Hustead 61

Broadly speaking, states that offer additional privacy protections include some combination of the following:

-

1. Statutes governing the disclosure of private information held by HIPAA’s covered entities. Some state statutes are more comprehensive and offer more protection than HIPAA. These statutes do not apply to law enforcement agencies.

-

2. Statutes governing the use of private health information related to specific medical conditions and communicable diseases. Alzheimer’s Disease and other cognitive disorders are not considered a communicable disease, generally statutes in this category would not apply to law enforcement agencies.

-

3. Statutes governing how specific state agencies can use and disclose private health information. Law enforcement agencies should focus on ensuring compliance with statutes in this category.

States that have enacted extensive statutory protections that govern how its agencies can use and disclose private health information. California’s Information Practices Act of 1977 (IPA) applies to state agencies and expands upon the constitutional guarantee of privacy by setting limits on the collection, management and disclosure of personal information including health information and applies to “state agencies, offices, officers, departments, divisions, bureaus, boards, and commissions.” 62 California’s IPA provides individuals with remedies for noncompliance including fines and penalties to be waged against agencies for intentional violation of any provision. 63 Therefore, state agencies with voluntary registries in California should be sure to review CA’s IPA to ensure compliance with the Act.

Some state statutes, such as North Carolina’s N.C. Gen. Stat. § 132-1.2, protect nonpublic health information held by any state agency from public inspection under the state’s Public Records Act.Reference Pritts, Choy, Emmart and Hustead 64 Municipalities and law enforcement agencies should review state law to ensure compliance with applicable state public records statutes. States that do not have statutes that explicitly govern state agencies’ use and disclosure of private health information with respect to public records request, should nevertheless maintain practices and procedures that protect private information from public disclosure, in order to establish confidence in registrants that their private health information will be protected.

The state of Arizona has enacted statutes governing the use of private health information related to specific medical conditions, such as communicable diseases, for certain HIPAA covered entities. 65 In the interest of protecting public health, certain communicable diseases must be reported to the local board of health or the state department of health, even in the absence of the individual’s authorization. 66 Pursuant to Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 36-621., “a person who learns that a contagious, epidemic or infectious disease exists shall immediately make a written report of the particulars to the appropriate board of health or health department.” 67 The statute further requires that “the report shall include names and residences of persons afflicted with the disease,” and “if the person reporting is the attending physician he shall report on the condition of the person afflicted and the status of the disease at least twice each week.” 68 In addition to the inflicted person’s name and address, the Arizona Department of Health Services Communicable Disease Report for Healthcare Providers must also include a phone number, date of birth, diagnosis and other occupational risk related information. 69 Arizona does not currently have state statutes in place that explicitly govern law enforcement agencies’ use and disclosure of private health information. Moreover, voluntary disclosure of health information regarding noncommunicable conditions like dementia would not apply under the aforementioned privacy and disclosure statute.

After a comprehensive review of relevant state and local law to ensure that registries comply with state health privacy statutes, voluntary registries for dementia and/or analogous conditions should adopt certain best practices to address potential ethical and privacy concerns. These best practices should include a statement of confidentiality affirming that private health information will remain confidential, as well as a statement to put registrants on notice that agencies will exempt private health information from disclosure under the state’s public records acts and freedom of information requests.

D. Privacy Concerns Related to Voluntary Registrations

Aside from legal concerns related to construction and application of voluntary registries, public uptake of voluntary registries is a significant barrier to the success of registry tools for people living with dementia. The ability to keep particular areas of one’s life private and to control disclosure of sensitive information is a widely recognized individual social and legal right in the US. Potential registry users cite a variety of privacy concerns that dampen enthusiasm for enrollment, including social stigma, insurability, and risk of exploitation for both people living with dementia and their caregivers.

In Western society, fear is commonly associated with dementia and societal stigma is widespread, leading some people with dementia or caregivers of people with dementia to avoid disclosing their dementia diagnosis for fear of negative public perception or social exclusion.Reference Batsch and Mittelman 70 In a global survey, dementia concealment was most common in Europe and the Americas, with a majority of respondents in some North American regions reporting that they attempt to hide their dementia. 71

Some cultures consider dementia with a variety of implications for privacy, including Chinese culture that views dementia as a source of family shame,Reference Dong and Change 72 or Hispanic culture that conversely views dementia as a common component of aging and need for family caregiving.Reference Flores, Hinton, Barker, Franz and Velasquez 73 In the United States in particular, a long history of structural violence and healthcare disparities has contributed to deeply held distrust of healthcare systems by African-American communities, leading to delays or avoidance in seeking care and services related to dementia.Reference Clark, Phoenix, Bilbrey, McMani, Escal, Arulanantham, Sisay and Ghatak 74 Therefore, cultural considerations related to dementia perception and privacy may exert significant impacts on uptake of voluntary dementia registries.

Other concerns that limit participation in voluntary dementia registries include the threat of being targeted by predatory scams and identity theft as a result of being exposed as an older adult with dementia, particularly as vulnerable elderly individuals are a known target for scams. For example, in Arizona, consumer fraud and identity theft is a common occurrence. In response, the Arizona Attorney General’s office has established a senior scam alert series, as well as a formal task force against senior abuse.

Risks of being targeted further dovetail with underlying distrust of public safety officials and police departments among certain groups of Americans. This distrust is particularly articulated in African-American communities and other communities of color within the context of policing. The Pew Research Center reported in 2019 that a majority of Black Americans perceive unfair treatment by the police.Reference Horowitz, Brown and Cox 75 Racial tensions, particularly between police and the Black community, experienced significant spikes in 2020. In addition to racial tensions experienced by Black Americans, Hispanic communities have experienced public safety targeting with specific concerns about deportation, including state policies like SB107076 in Arizona and federal public charge immigration policies during the Trump administration. 77

More broadly than public distrust of public safety officials and police departments among ethnic groups, Americans report increasing levels of general distrust of government. According to the Pew Research Center (2019)Reference Rainie and Perrin78, Americans both perceive and report declining trust in government. Survey findings indicate that older Americans retain higher levels of trust in government than younger generations. However, it is important to note that for older adults living with dementia, the decision to enroll in a voluntary registry may lie with younger family members who have lower levels of trust in government, and who may be less likely to trust public agencies with protecting individual information through an active voluntary registry program.

E. Liability Considerations Posed by Voluntary Registries

This section presents legal liability considerations municipalities and law enforcement agencies should evaluate when implementing active voluntary registries. Tort and contract law serve as a legal basis for increased liability risk for agencies with voluntary registries. Under both legal theories a breach of duty by one or more parties is the legal basis for liability. In contract law, the breach is referred to as breach of contract and occurs when one party does not fulfil its duties under the contract. In tort law, the breach is referred to as a breach of duty and occurs when one party fails to fulfil its duty of care to another party.

Under a tort theory of liability, the relevant issue to consider within the context of voluntary registries, is whether a voluntary registry creates a special relationship between the registrant with dementia and the agency, thereby triggering a corresponding duty of care greater than that owed to the general public. Whether a special duty exists depends on the specific facts and circumstances involved, as well as state laws regarding tort liability. Under a contract theory of liability, the relevant issue to consider is whether voluntary registries create a tacit or implied contract between the state, municipality, or county holding the registry, and the registrant, by creating the expectation that responders will prioritize or respond to emergency calls in a particular manner.

To date, the discussion regarding legal liability of local agencies with voluntary registries has primarily focused on emergency management registries that register non-ambulatory individuals, or those with physical or cognitive limitations, in preparation for a local emergency, catastrophic event or natural disaster (and even this area of discussion requires additional exploration). While there is scare data or case law addressing liability within the context of voluntary registries for individuals with dementia, a look into emergency management registries can help inform best practices. Websites and registration forms often state that participation in the registry does not guarantee priority response.Reference Flowers 79 Instructions for placement typically require registrants sign a liability waiver, releasing the agency and its agents and employees from claims related to the use, disclosure, or failure to act upon the information provided.Reference Flowers 80

When considering liability, a major difference between emergency management/assistant registries and voluntary registries for dementia is that in the case of emergency management registries, emergency personnel and first responders are dealing with large scale disasters affecting an entire jurisdiction. This makes it very difficult to prioritize assisting all individuals placed on the emergency registry. Emergency management registries assist law enforcement in proactively identifying citizens in need of assistance during large-scale disasters when an entire region likely needs assistance and resources are spread thin. Conversely, voluntary registries for dementia exist to assist law enforcement responding to emergency calls involving a single registered individual.

We argue that the state, municipality, or county’s risk for liability in maintaining voluntary registries for dementia or other special needs is substantially less than liability for agencies with emergency management/assistant registries, as a result of law enforcement’s ability to focus on the individual registrant in distress when responding to an emergency call. For example, in response to an emergency call to law enforcement to assist in the search and rescue of an individual with dementia, responders are able to utilize registry information to direct resources and attention to locating the lost registered individual. In contrast, during a wide-scale emergency, first responders are tasked with balancing the needs of all registered individuals and the entire community and will have fewer resources available to them to assist all individuals placed on the registry. There is a greater likelihood that responders cannot prioritize locating and rescuing all individuals placed on an emergency management system during a natural disaster or catastrophic event, thus increasing potential liability claims for those agencies.

Despite the lowered risk for liability claims, disclaimers in voluntary registries for dementia should be used to help create realistic expectations for registrants and caretakers regarding how emergencies involving individuals with dementia or other special needs will be handled. Authorizations can also help registrants better understand how, when, and by who, private health information will be used.

F. Ethical Considerations and the Use of Disclaimers/Authorizations in Registry Forms

In order to ensure ethical best practices for active voluntary registries, we posit that registries should include disclaimers and authorizations in their registry forms to provide clarity and transparency in how private data will be used.

Disclaimers should clearly inform registrants that placement on the voluntary registry does not guarantee a particular outcome in the event of an emergency situation. The Irvine, (CA) Police Department’s Return Home Registry section on their website, includes a statement notifying registrants that, “This program does not guarantee the safe return of your loved ones, but it will provide officers with an additional tool to locate and return your loved one.” 81 Similarly, Calhoun’s (GA), Special Needs Database includes a section entitled “Acknowledgment” which states:

It is further understood that completion of this form and participation in the Calhoun Police Department “Special Needs Registry” is voluntary and cannot guarantee and is not intended to convey and warrant, either express or implied, as to outcomes, promises, or benefits from the use of this form and participation in this program. Use of the Calhoun Police Department “Special Needs Registry” constitutes acknowledgement and acceptance of these limitations and disclaimers. 82

Registry forms should also clearly state that participation is entirely voluntary and require signed consent via an “acknowledgment” where the registrant agrees to voluntarily share private health information to participate in the registry. Some agencies require registry participants to regularly update their information; some even requiring they be updated on an annual basis. Acknowledgments should also state who will have access to private health information and under what circumstances that information is shared. Forms should also advise registrants that they can discontinue participation and revoke consent at any time.

The City of Maricopa, Special Needs Registry states:

I hereby give my permission for the Maricopa Police Department to retain and distribute the information contained in this registration form to other first responder personnel for the sole purpose of identification and protection of the person identified above in an emergency or crisis situation. I acknowledge the information being provided is truthful, current, and valid and that I am authorized to submit it on my own behalf, or as the legal guardian, with the authority to submit on the behalf of another. It is further understood that my completion of this form and my participation in the Special Needs Registry is completely voluntary, without guarantee, and is not intended to convey or warrant either expressly or implied any outcomes, promises or benefits from the use of this form and participation in this program. Use of the Maricopa Special Needs Registry constitutes my acknowledgement and acceptance of these limitations and disclaimers. I also acknowledge that is my responsibility to keep the information on the registry up to date. 83

Disclaimers and acknowledgements are by no means a foolproof mechanism to protect agencies from liability, nor should legal disclaimers and acknowledgments allow registry hosts to shed legal and ethical responsibility for safeguarding and protecting sensitive health information, nor for diligently responding to emergency calls. However, including these statements in registry forms may help set expectations for registrants about who will have access to their private health information and how potential emergencies may be handled. The issue of whether the inclusion of disclaimers and acknowledgements in registries has been effective in preventing a finding of liability based on tort or contract law warrants further exploration as more communities across the US implement voluntary registries to assist law enforcement search and rescue efforts.

VI. Concluding Thoughts and Considerations

Communities should consider two growing trends when considering how to best meet the needs of individuals with dementia and their caregivers. First, communities should consider the rapidly increasing number of individuals diagnosed with dementia both nationally and within individual jurisdictions. Second, policy makers should track and consider the number of aging adults choosing to remain in their homes, living with family members, or in other community settings. Increasing costs associated with assisted living facilities, and concerns regarding COVID-19’s increased risk to elderly populations living in congregate settings, where 40% of U.S. deaths from COVID-19 occurred in the early months of the pandemic,Reference Kwiatkowski, Nadolny, Priest and Stucka 84 are two factors that will likely contribute to the decision to age at home for years to come. Given these very real financial and safety concerns, the number of adults residing at home with dementia will likely continue to increase.

As elderly populations increase within a given community, so too does the likelihood for an unexpected encounter between police and individuals with dementia. The behavioral and psychological symptoms associated with dementia make it even more imperative that first responders, including police officers, receive knowledge and skills training focused on people living with dementia. In addition to training, first responders need access to tools and strategies to recognize signs and symptoms of dementia in order to deescalate confrontations and to efficiently locate those who go missing. Innovative public safety strategies that support caregiver efforts by providing caregivers with the infrastructure to plan in advance of an emergency situation can reduce negative outcomes when individuals go missing, while also reducing caregiver stress and burnout, in turn improving outcomes for all parties.

As registries become more commonplace across the US, outreach and education can address concerns around the ethical, legal, and privacy concerns that may otherwise deter agencies from hosting registries and individuals from registering. While active voluntary registries are by no means a panacea for all dangers currently facing the growing population of people living with dementia, the more individuals who voluntarily register, the greater the likelihood that should these individuals ever go missing or have an unexpected interaction with police, they will return home unharmed.

Evidence indicates that first responders including law enforcement should use technology, and proactive processes that will enhance efforts to locate those who are reported missing, while collaborating with community service agencies to address the needs of residents with dementia and their families. 85 It is worth noting that some remain skeptical about the effectiveness of voluntary registries as a viable solution for increased interaction between first responders and individuals with disabilities, citing the risk of further stigmatization of people with certain diagnosis and privacy concerns.Reference Collins 86 Some advocates for individuals with disabilities worry that registries may not result in better outcomes and may in fact have unintended negative effects during interactions if first responders know they are encountering an individual with a specific diagnosis due to bias and stigma around certain cognitive disorders. 87 Proactive community-based solutions, like voluntary dementia registries, should go hand in hand with dementia training in order to raise police officer competence in handling emergencies involving individuals with dementia.

It is encouraging to see voluntary registries implemented in cities located in vastly different geographic locations across the US. From Irvine, California to Hendersonville, North Carolina, communities clearly see the value in utilizing voluntary registries as one approach to serving and protecting the dementia population. Cities like Phoenix, with a large and growing population of older adults living with dementia, have a unique opportunity to create partnerships between the public and private sectors to address the growing needs of this vulnerable population. The need to implement proactive strategies is particularly critical in areas experiencing exponential growth such as Arizona. Police and sheriff’s departments located in different regions throughout the state have successfully implemented voluntary registries.

As registries become more commonplace across the US, outreach and education can address concerns around the ethical, legal, and privacy concerns that may otherwise deter agencies from hosting registries and individuals from registering. While active voluntary registries are by no means a panacea for all dangers currently facing the growing population of people living with dementia, the more individuals who voluntarily register, the greater the likelihood that should these individuals ever go missing or have an unexpected interaction with police, they will return home unharmed. If larger cities in Arizona, such as Phoenix, consider registries as a part of a larger policy regime to address the needs of the dementia population while incorporating community outreach as part of their strategy for successful implementation, registries will likely become more accepted as an effective intervention strategy for law enforcement and are more likely to be systematically implemented across the country. Phoenix has the opportunity to lead the nation in its approach to addressing its rapidly growing dementia population by becoming a model for other large cities across the U.S. Partnerships between the police and the community to implement solutions to reduce adverse outcomes for individuals with dementia, have the added benefit of potentially increasing trust between the public and law enforcement, laying the foundation for future collaboration and community oriented solutions to public health crises.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our deepest appreciation to staff and leadership at the following agencies for their time and effort to contribute to this project and for their assistance in the collection of our data taking. Calhoun, Georgia, Police Department, Chandler, Arizona, Police Department, Hendersonville, North Carolina, Police Department, City of Maricopa, Arizona, Police Department, Irvine, California, Police Department, Phoenix, Arizona, Police Department, Mt Juliet, Tennessee, Police Department, Pima County, Arizona, Sheriff’s Department, Polk County, Florida, Sheriff’s Department, Prescott, Arizona, Police Department, Rowlette, Texas, Police Department, Prescott Valley, Arizona, Police Department, San Diego, California, Sheriff’s Department, Tempe, Arizona, Police Department, Tampa, Florida, Police Department.

Note

Dr. Ross served as a special advisor in health policy to the Mayor of Phoenix, Arizona, during the preparation of the manuscript. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.