In this land blessed by hydrocarbons, through the present Regional Autonomy Statute we will form a self-government that allows us […] to make Gran Chaco the main centre of development in Bolivia, an articulating centre of Bolivianness and geographical reference point of the South American Chaco. The tenacious struggle of the original chaqueños to shake off all dependency flowed in the people that bravely fought for 45 per cent of the hydrocarbon royalties; subsequently demanded autonomy and conquered it democratically through the vote, as the corollary of its historically autonomous vocation. Here is the First Autonomous Statute of the Gran Chaco Region that expresses the feeling and the aspirations of the Chaco people. LONG LIVE GRAN CHACO!

− Excerpt from preamble, Regional Autonomy Statute of the Gran Chaco, September 2016Footnote 1Introduction

On 20 November 2016, residents of Gran Chaco ProvinceFootnote 2 in Tarija Department in south-east Bolivia voted by popular referendum to approve a statute that established Gran Chaco as Bolivia's first ‘autonomous region’ – one of several levels of autonomy recognised in Bolivia's 2009 Constitution.Footnote 3 Underpinning Gran Chaco's successful autonomy bid was a claim to receive and administer 45 per cent of the hydrocarbon royalties allocated to Tarija Department, which contains most of Bolivia's gas reserves.Footnote 4 These resources constitute the main source of national income in Bolivia and the economic basis for the ‘process of change’ implemented by President Evo Morales from 2006. The recognition of Gran Chaco as an autonomous region makes this remote, semi-arid and sparsely populated province, in fiscal terms at least, the richest in Bolivia.

Gran Chaco's regional autonomy project is illustrative of how identity, territory and political power are being remapped in the context of Bolivia's recent hydrocarbon boom and neo-extractivist development model, in ways that are producing new territorialities. What is perhaps most striking, however, is that this elite-led extractivist project is being advanced and legitimised through the constitutional framework of Bolivia's plurinational state. This article considers the historical evolution of resource regionalism in the Chaco, its intersection with broader processes of state formation under the Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement towards Socialism, MAS) government (2005–19; 2020–present) and its implications for Indigenous decolonial struggles.

As I will go on to describe, demands for regional autonomy reflect long-standing ‘resource grievances’ related to the Chaco's status as a gas-producing region and its marginality within departmental and national politics.Footnote 5 This project gained a new lease of life under the MAS government, which saw regional autonomy as a means of weakening the power of Tarija's right-wing departmental elite and consolidating its own power over the Chaco and its gas fields. Gran Chaco's regional autonomy thus demonstrates how Indigenous visions of a plurinational state are being appropriated by, and subordinated to, the territorial dynamics of a neo-extractivist development agenda, providing a basis for new (but historically familiar) sovereign alignments between state resource interests and agrarian elites in the Chaco.

The article also considers the implications of regional autonomy for the Chaco's Indigenous peoples – the Guaraní, Weenhayek and Tapiete – whose ancestral territories contain the region's most important gas reserves. While regional autonomy began as an elite-led project that excluded them, these Indigenous peoples have now achieved significant representation within Gran Chaco's regional assembly. However, I argue that racialised inequalities, clientelist relations and bureaucratic constraints limit what Indigenous representatives are able to achieve within such political spaces. Meanwhile, Indigenous territorial claims continue to be obstructed by regional elites and the MAS government, and the direct impacts of extraction in these territories continue to accumulate. Notwithstanding these limits, the testimonies of Indigenous representatives make clear that they are not simply political instruments of regional and national elites, but are slowly and patiently seeking to carve out spaces within the pluri-extractivist state to pursue their own claims to postcolonial recognition and resource justice.

The article is structured as follows. The first section sets out a theoretical framework for understanding the Chaco's regional autonomy project at the intersection of extractivism and plurinationalism. The second section describes the historical emergence and evolution of Gran Chaco's regional autonomy project from the 1930s to the present. The final section explores the shifting position of Chaco Indigenous peoples within this regional autonomy project, the constraints faced by elected Indigenous representatives and how they reflect on their positions in relation to broader Indigenous agendas for decolonising the state.

Research for this article involved institutional ethnography, documentary analysis and interviews conducted during three two-month trips in 2016, 2017 and 2019. This included several periods of participant observation within the Autonomous Regional Assembly of Gran Chaco, where I discussed regional autonomy and day-to-day politics with Indigenous representatives, non-Indigenous politicians and technical staff, and observed political meetings, administrative processes and civic events. In 2017, I conducted interviews with chaqueño political leaders and Indigenous representatives within the Chaco's regional assembly and Tarija's departmental legislative assembly. The article also draws on my broader engagements with Indigenous movements in the Chaco since 2008, which have focused primarily on their struggles for territory. Throughout the article, pseudonyms are used to protect the identities of research participants.

Territory, Extractivism and Plurinationalism

The recent extractive industry boom in Latin America and the rise (and in some cases fall) of leftist governments has generated a vast literature exploring the shifting dynamics of extractivism in the region, including its implications for citizenship, the environment and Indigenous peoples.Footnote 6 Much of this literature has focused on how extractive industry projects threaten and are resisted by local groups, producing socio-environmental conflicts. In this regard, the territorial dynamics of ‘neo-extractivist’ or ‘progressive extractivist’ regimes have much in common with those of their neoliberal counterparts.Footnote 7 Bolivia and Ecuador have been seen as emblematic of the contradictions between leftist states’ discourse on Indigenous rights and the environment and dependence on resource rents to finance social and infrastructure spending.Footnote 8 Maristella Svampa argues that such conflicts are giving rise to a new ‘eco-territorial turn’, as Indigenous and environmentalist movements converge around forms of place-based resistance to extractivism.Footnote 9

Yet the territorial dynamics of extractivism are not limited to environmental dispossession and the local defence of territory. Diverse local actors also seek to shape how extraction happens and who benefits from it.Footnote 10 Where efforts to prevent extraction from happening fail (as they often do), issues of environmental governance, access to employment, compensation and the distribution of resource rents often emerge as the enduring focus of political contestation. Of course, hydrocarbon companies actively seek to channel local agency into demands for recognition and benefit-sharing.Footnote 11 Such local engagements with extraction produce new forms of territoriality, which may challenge, as well as articulate with, resource nationalist projects.Footnote 12 Felipe Irarrázaval describes the emergence of ‘metano-territorialities’, as different social groups develop spatial practices that seek to develop to ‘modify, refuse or access benefits from the natural gas production network’.Footnote 13

In Bolivia, nationalist articulations of nature and nation under the MAS government have been accompanied by ‘competing modes of spatial practice’ as local actors seek to reconfigure the relationship between citizenship and the subsoil ‘from the ground up’ – from right-wing departmental autonomy movements, to mining cooperatives seeking direct agreements with transnational companies, to gas-fuelled visions of Indigenous autonomy.Footnote 14 The Chaco region of Tarija, which contains most of Bolivia's gas reserves, has been a key site for subnational territorial projects linked to the governance of gas.Footnote 15

A focus on such extractivisms ‘from below’ challenges state-centric analyses of leftist governments, revealing how political authority and state formation are not pre-given or static, but are constituted through local conflicts over land and resources.Footnote 16 As Michael Watts argues in the Nigerian context, ‘access to resource rents amplifies […] subnational institution-making; politics becomes then a massive state-making machine’.Footnote 17 While proponents of resource-curse theory have long observed such dynamics, recent work by geographers and anthropologists looks beyond economic competition to situate such conflicts within longer postcolonial struggles over territory, citizenship and nation.Footnote 18 This work provides an important starting point for understanding Gran Chaco's regional autonomy project.

Yet my interest, in this article, is not merely in how local state-making occurs in neo-extractivist states, but in the implications for decolonising the state and territory. It is here that the concept of plurinationalism is relevant, as a key point of articulation between Indigenous decolonial projects and local state formation in Bolivia. Plurinationalism has been understood by Bolivian intellectuals as a response to the crisis of a unitary state inherited from the colonial and republican periods, which failed to reflect the plurality or ‘motley’ (abigarrado) nature of the Bolivian population.Footnote 19 Concretely, the vision of a plurinational state in Bolivia emerged from Indigenous movements and their long-standing claims to self-governance of their ancestral territories.Footnote 20 It was developed by the Plurinational Constituent Assembly of 2006−8, where representatives of Indigenous and peasant organisations participated in rewriting Bolivia's national Constitution.Footnote 21 The 2009 Constitution redefines Bolivia as a ‘plurinational state’ and recognises Indigenous peoples’ right to self-governance through the constitution of autonomías indígenas originarias campesinas (Indigenous peasant autonomies, AIOCs), among other measures.Footnote 22 The Constitution identifies three routes to Indigenous autonomy: (i) the conversion of already-existing municipalities; (ii) the conversion of tierras comunitarias de origen (Indigenous community lands, TCOs), renamed territorios indígena originario campesinos (Indigenous peasant territories, TIOCs); and (iii) the creation of regional Indigenous autonomies composed of two or more converted municipalities.

As other scholars have noted, the 2009 Constitution represents a ‘domestication’ of Indigenous peoples’ vision of autonomy.Footnote 23 Moreover, the implementation of Indigenous autonomy in practice has stalled due to a combination of procedural obstacles and the MAS government's economic dependence on resource extraction in Indigenous territories.Footnote 24 As such, previous scholarship has tended to treat extractivism and plurinationalism as contradictory forces within Bolivia's ‘process of change’. Without contesting this contradiction between Indigenous autonomy and extractivism, this article argues that extractivism and plurinationalism are also becoming articulated in local processes of territory and state formation in the Bolivian Chaco, with significant consequences for Indigenous decolonial projects. Specifically, Gran Chaco's regional autonomy process shows how local dynamics of extractivist state formation are redefining the meaning and content of plurinationalism in the Chaco, in ways that marginalise alternative Indigenous visions of territory and autonomy. I use the term pluri-extractivism to describe and critique this articulation.

One the one hand, I chart how regional elites’ resource claims have been reframed, legitimised and institutionalised within the framework of Bolivia's plurinational state – the 2009 Constitution and the 2010 Ley Marco de Autonomías y Descentralización (Autonomy and Decentralisation Framework Law). I argue that the MAS government has supported this autonomy process as a means to consolidate its own power within the gas-rich Chaco in the face of departmental opposition in Tarija. Meanwhile, Indigenous peoples – the intellectual architects and intended beneficiaries of the plurinational state – continue to have their claims to territory effaced and obstructed, both by local agrarian elites and by an extractivist state.

Yet, plurinationalism and extractivism are also becoming articulated in a second way, which is of relevance to this article. Indigenous and peasant organisations have emerged as active participants in struggles over gas-rents distribution in Tarija, where political actors cannot avoid engaging in the politics of extraction.Footnote 25 In this context, local control of gas rents is seen by diverse local actors as an essential part of building a plurinational state; as I was frequently told on recent trips to Tarija, ‘sin recursos no hay autonomía [without resources there is no autonomy]’. While Indigenous demands for a direct share of national or departmental hydrocarbon rents have been frustrated by elite opposition and formal Indigenous autonomy remains inaccessible, some Indigenous leaders see occupying positions within local state institutions as a means of directing hydrocarbon rents towards rural Indigenous communities, who suffer from chronic underinvestment alongside the direct socio-ecological impacts of extraction.

The construction of regional autonomy in Gran Chaco sits at the intersection of these two processes. On the one hand, chaqueño elites have sought to include Indigenous peoples in their regionalist project as a means to gain political legitimacy and increase their capacity for social mobilisation (such as road blockades) in the face of strong opposition from departmental elites. On the other hand, Indigenous organisations have actively fought for inclusion in regional autonomy as a means to advance their own political agendas – inclusion within regional planning processes, the allocation of state funds to Indigenous development priorities, and the breaking down of historic structures of racialised rule that frame Indigenous peoples as incapable of holding political office or managing resources. It is important to note that Gran Chaco's regional autonomy is just one expression of how plurinationalism and extractivism are being articulated, with its own particular set of dynamics. Further research is required to examine other iterations of pluri-extractivism in Bolivia – and indeed, whether the term has any broader resonance beyond the Chaco. I now turn to the origins of regional autonomy in the Chaco, which underline the historical and geographical specificity of this project.

The Origins of Regional Autonomy in the Bolivian Chaco

A Neglected Hydrocarbon Frontier

Stretching from the sub-Andean mountain range of Aguaragüe in the west to the arid Chaco plains in the east, the Chaco region of Tarija Department has historically been at the political and imaginative margins of the Bolivian nation-state. While non-Indigenous settlement in the region began in the late eighteenth century, strong military resistance by the Guaraní meant that Bolivian state forces did not have military control of the region until the late nineteenth century.Footnote 26 The first paved road connecting the Chaco to the Bolivian altiplano (highlands) and the capital La Paz was not built until the 1930s. This historic isolation has contributed towards a strong regional identity, with most residents of the Chaco identifying themselves as chaqueños rather than as tarijeños.

The 1932–5 Chaco War with Paraguay marked a turning point in the region's history. The war brought thousands of largely poor Aymara- or Quechua-speaking peasants from the Andes to fight in defence of the Chaco's oil and gas reserves, where many of them perished due to extreme heat, lack of training and equipment and poor military leadership.Footnote 27 Although Paraguay won the war and was awarded three-quarters of the disputed Chaco Boreal, the portion that remained in Bolivia contained some of South America's most important oil and gas reserves. The end of the war saw an intensification of hydrocarbon development, following the creation of the Bolivian state-owned oil company Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB) in 1936 and nationalisation of hydrocarbons reserves in 1937. This period also brought many new settlers to the region, as the Bolivian state encouraged ex-combatants to occupy the Chaco's gas-rich lands, a process that exacerbated Indigenous dispossession and the spread of forced-labour practices.Footnote 28

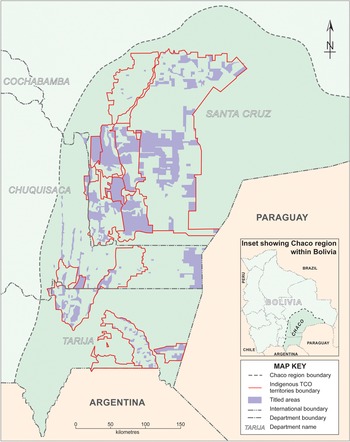

The Chaco's emergence as a hydrocarbon frontier, combined with its marginality to national and departmental development, created the conditions for the first iteration of a regional autonomy movement. Following the Chaco War, the 1941 Royalties Law allocated an 11 per cent royalty to hydrocarbon-producing departments.Footnote 29 In Tarija Department, this money was managed by departmental elites based in the temperate colonial city of Tarija at some distance from the arid Chaco and its gas fields (see Figure 1). Few of these resources were channelled into Gran Chaco Province, which continued to lack basic infrastructure. In 1983, following Bolivia's return to democratic rule, politicians from Gran Chaco began meeting with political leaders in the Chaco region of neighbouring Santa Cruz and Chuquisaca departments.Footnote 30 The result was a joint proposal for the creation of a ‘tenth department’ in the Bolivian Chaco. Known as the Pacto de Quebracho, this agreement was based on shared grievances regarding the centralism of national and departmental governments and an agro-industrial vision of regional economic development.

Figure 1. Map Showing Location of Gran Chaco Province in Tarija Department, Bolivia

Source: Map compiled by Chris Orton in the Cartographic Unit, Department of Geography, Durham University.

A 1989 newspaper article entitled ‘The Chaco … German Busch Department?’ (see Figure 2) is illustrative. Detailing the sacrifices of the disastrous Chaco War, the authors lament:

After the traumatic military contest, the country didn't know any more of the Chaco and its people. On looking there, governments only saw oil deposits and towers. They never understood what the Chaco is … [the Chaco's] historic unity has always been submerged in backwardness and dependency, so its future always had to await solutions in three capitals of different departments (Santa Cruz, Sucre and Tarija), that could never fulfil the hopes of this people.Footnote 31

Figure 2. ‘Gran Chaco and Its Potential’

Note: Illustration from 1989, which depicts the province as a site of hydrocarbon development, agro-industry and cattle ranching with commercial links to Argentina and Paraguay. No reference is made to the region's Indigenous peoples.

Source: Ramiro Antelo León and Oscar G. Montes, ‘El Chaco … Departamento German Busch?’ (1989, found in archive of Centro de Estudios Regionales de Tarija).

The authors go on to make a case for regional autonomy, asking: ‘Why not a Department of the Chaco? What mean interests could prevent […] us from overcoming this arbitrariness of our history through which this vigorous region was severed, fragmented and condemned to live in three different and faraway Departments?’Footnote 32 As Figure 2 makes clear, Chaco Indigenous peoples were not considered within this vision of regional development – other than perhaps as an element of the Chaco's historic ‘backwardness’.

While this tenth department never materialised, the threat it posed to Tarija's departmental elites played an important role in ongoing negotiations over the inter-departmental distribution of gas rents. In parallel with the Pacto de Quebracho, leaders in Gran Chaco Province put forward a demand to receive 45 per cent of the 11 per cent of gas royalties received by Tarija Department, based on the argument that Gran Chaco represents 45 per cent of Tarija Department's territory. Tarija's departmental government responded by passing Resolution 16/83, which established that 45 per cent of annual hydrocarbon royalties generated by Gran Chaco Province should be invested in the province. However, there were repeated delays in transferring these resources and most of the money went to Yacuiba, the seat of the sub-prefecture and the most populous of Gran Chaco's three municipalities. This was exacerbated by the 1994 Ley de Participación Popular (Popular Participation Law), which allocated state funds to municipalities based on population. As local politician Fermin Ramos explained: ‘First there was a draining centralisation in the department and later there was a centralisation in Yacuiba as the capital of the province […] from there the spirit of being autonomous was born – to be able to manage our own resources, to be able to elect our own authorities and to be able to plan our own development.’Footnote 33

As this brief overview makes clear, Gran Chaco's regional autonomy project has its origins in long-standing ‘resource grievances’ regarding the Chaco region's emergence as a hydrocarbon frontier and its marginality to national and departmental development.Footnote 34 Nevertheless, the realisation of this project has been made possible by a set of more recent political transformations: first, the gas boom of the 1990s and resulting struggles over the governance of the subsoil that marked Morales’ rise to power; and second, the institutionalisation of Indigenous visions of a plurinational state under the 2009 Constitution and 2010 Autonomy and Decentralisation Framework Law.

A Neo-Extractivist Alliance

As has been widely discussed, Bolivia's MAS government emerged from popular responses to neoliberalism and, more specifically, demands for the renationalisation of Bolivia's hydrocarbon reserves – a story in which the Chaco of Tarija (which contains approximately 85 per cent of these reserves) played a central role.Footnote 35 In 2003, plans to allow export of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the Chaco to the United States via Chile, Bolivia's historic rival, sparked national protests and demands for a renationalisation of Bolivia's gas fields. Following the deaths of 80 people in clashes with the police in the 2003 Gas War, President Sánchez de Lozada was forced to resign, paving the way for the election of Morales two years later. On assuming office in January 2005, Morales passed the ‘Heroes of the Chaco’ Decree nationalising hydrocarbons. The Chaco's gas fields were theatrically occupied by the military while contracts with transnational oil companies were renegotiated.Footnote 36

These national struggles over the governance of the subsoil were accompanied by an escalation of political conflict in Gran Chaco Province relating to the transfer and distribution of hydrocarbon royalties by Tarija's departmental government. In 2001, a 14-day road blockade in the Chaco led Tarija's departmental council to pass a new resolution determining that Gran Chaco's 45 per cent would be distributed equally between its three municipalities.Footnote 37 Ongoing delays with the transfer of funds led to further roadblocks in 2002. On 14 February 2004, Chaco leaders from Tarija, Santa Cruz and Chuquisaca departments formally renewed their pact to promote the creation of a tenth department. These struggles occurred in the context of an explosion of hydrocarbon development in the Chaco and a dramatic increase in royalties and Direct Hydrocarbon Tax flowing into the accounts of the departmental prefecture of Tarija.Footnote 38

The national political crisis of 2003–5 provided a context for a strategic alignment between these resource-nationalist and resource-regionalist projects. After being forced out by social protest in 2003, President Sánchez de Lozada was succeeded by his former vice-president Carlos Mesa. Mesa's multi-party interim government (2003–5) saw ongoing social protest from labour unions, right-wing autonomist movements, and the growing MAS party led by Morales. Amidst this social upheaval, Mesa made a pact with the leading chaqueño politician Wilman Cardozo, who agreed to support Mesa's government in exchange for Mesa's support for the Chaco's autonomy claim.Footnote 39

This pact was renewed by Morales, who was elected president in 2005 after Mesa was forced from office. Morales’ first term in office was rocked by coordinated autonomy campaigns by lowland departmental elites (2006–8), who viewed the new government as a threat to the established racial-spatial order and (in Tarija and Santa Cruz) to their own aspirations for control of the Chaco's gas wealth.Footnote 40 In this context, Morales viewed Gran Chaco's regional autonomy project as a means to weaken Tarija's departmental autonomy campaign and strengthen central government control over Gran Chaco's gas fields, which provided the material foundation for his entire ‘post-neoliberal’ development project.

Contestation between a resource-nationalist government and right-wing campaigns for departmental autonomy thus provided a new opportunity for local non-Indigenous elites in Gran Chaco to pursue their historic claim for regional autonomy. While chaqueño leaders did support a 2006 referendum on departmental autonomy, they ultimately continued their alliance with the MAS government on the condition that it agreed to hold a binding referendum on regional autonomy in Gran Chaco Province.Footnote 41 This referendum was held in conjunction with the referendum on Bolivia's new Constitution on 6 December 2009 and asked ‘Are you in agreement that the province enters a regime of regional autonomy?’ The ‘yes’ vote won, with a majority of 90 per cent. The victory was followed by the establishment of the Asamblea Regional del Gran Chaco (Regional Assembly of Gran Chaco Province), tasked with elaborating a regional autonomy statute.

Despite this victory, regional autonomy continued to be seen by many in the Chaco as a result of political manoeuvres by MAS and a few chaqueño politicians rather than a genuine grassroots demand. When I visited the region in 2011–12, 2014, 2016 and 2017, the views of local residents appeared mixed, with demands for greater state spending tempered by critiques of self-serving local politicians. Radio and press coverage questioned the work of the regional assembly, which was critiqued for being primarily concerned with its own survival. Meanwhile, Tarija's departmental elites denounced the whole autonomy project as ‘unconstitutional’. As such, the Estatuto Autonómico Regional (Regional Autonomy Statute) was elaborated in a climate of uncertainty and contestation. Nevertheless, when the statute was put to a popular referendum in Gran Chaco Province on 20 November 2016, the ‘yes’ vote won with a resounding 72.4 per cent of votes (versus 27.6 per cent for ‘no’), paving the way for the establishment of an executive branch of the regional government in 2017. Finally, this gave the Chaco's autonomy project a more legitimate and permanent status.

The above discussion demonstrates how the political upheavals that marked Morales’ rise to power – centring on conflicts around the governance of the Chaco subsoil – provided new openings for chaqueño leaders to pursue their historic claim to regional autonomy. Beyond the contingencies of elite political manoeuvring, what perhaps stands out most in this account is that the MAS government sought to align itself not with Indigenous organisations and territorial projects in the Chaco – the architects and supposed beneficiaries of a plurinational state – but with provincial elites pursuing a regionalist project from which Indigenous peoples were until recently excluded. Even more surprising is that the discursive and legal framework for advancing regional autonomy was precisely that of plurinationalism.

Situating Regional Autonomy within a Plurinational State

While the plurinational state was conceived of by Indigenous organisations in Bolivia as a means to transform the colonial structure of the state and accommodate their long-standing demands for self-governance of their ancestral territories, the concept of autonomy within the 2009 Constitution is not limited to Indigenous peoples, but encompasses a variety of forms of political decentralisation. For example, departments are defined as ‘autonomous’, while non-Indigenous peasants can be included in the AOIC category. As Raúl Prada observes, this is ‘an institutional plural state’, composed of ‘multiple territorial ordinances’, including ‘Indigenous territorialities, local geographies, regional geographies and national cartographies’.Footnote 42 The 2009 Constitution defines regional autonomy as part of the territoriality of the plurinational state, noting that ‘in exceptional cases, a region can be formed by a single province’.Footnote 43 Given that the political pact between the MAS and chaqueño elites was already in place in 2009, one wonders if this clause might have been written with Gran Chaco in mind.

The 2010 Autonomy and Decentralisation Framework Law provides a legal framework for the implementation of these different forms of autonomy. A region is defined here as:

A continuous territorial space composed of various municipalities or provinces which doesn't transcend the limits of the department, which has as its objective to optimise the planning and public management for integral development, and which constitutes a space of coordination and concurrence of public investment. Indigenous peasant territories, decided by their own norms and procedures, can be part of the region.Footnote 44

Regional autonomy excludes legislative competencies and is limited to regional planning based on ‘minimum goals of economic and social development […] according to the conditions and potentialities of the region’.Footnote 45 The Law places emphasis on the representation of Indigenous peoples and territorial entities within regional autonomy; not only can autonomous regions be demanded by Indigenous peoples, but Indigenous peoples are to be included in the regional planning process, including through representation in a regional economic and social council.Footnote 46

While regional autonomy began as a project of non-Indigenous chaqueño elites from which Indigenous peoples were excluded, plurinationalism has thus provided the legal and constitutional framework for its implementation under the MAS government. Plurinationalism also represents a new discursive terrain for regional autonomy, enabling it to be reimagined as part of a wider process of building a plurinational state in Bolivia. Moreover, this plurinational framing has contributed towards opening spaces for Indigenous participation in the construction of regional autonomy in the Chaco. I now turn to examine the implications of these articulations for Chaco's Indigenous peoples and their decolonial projects.

Navigating Pluri-Extractivism: Indigenous Peoples and Regional Autonomy

From Exclusion to Incorporation

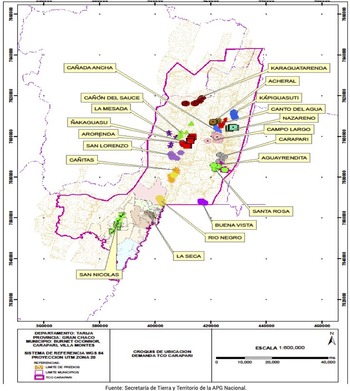

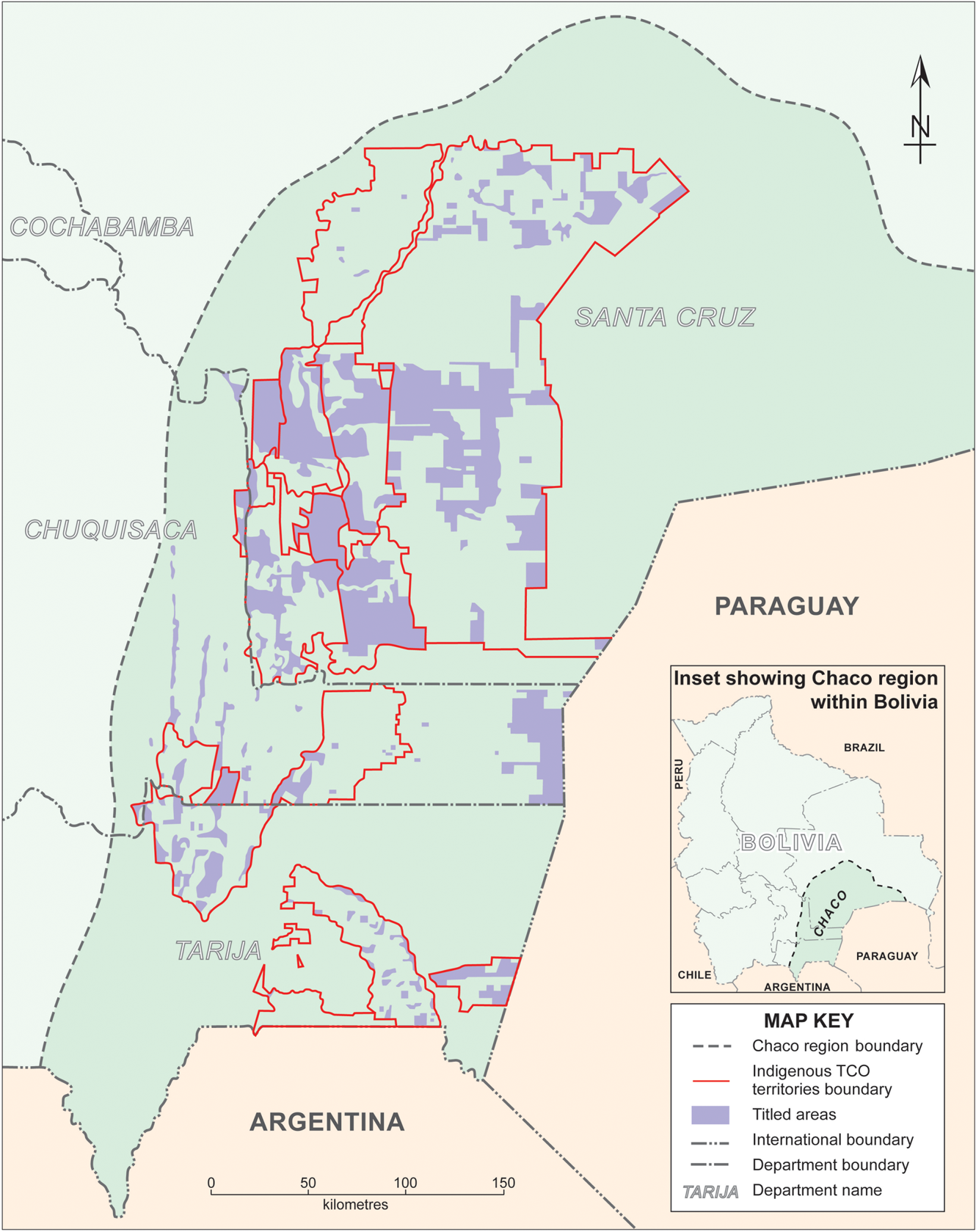

Gran Chaco Province is home to three Indigenous peoples, the Guaraní, Weenhayek and Tapiete. Following a history of state-backed territorial dispossession, these Indigenous peoples began organising in the late 1980s around demands for territory. The 1996 Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agraria (National Institute for Agricultural Reform, INRA) Law led to the recognition of five territorial claims within the province: TCO Weenhayek, TCO Yaku-Igua (Guaraní), TCO Tapiete, TCO Itika Guasu (Guaraní) and TCO Karaparí,Footnote 47 a Guaraní territorial claim recognised by the Bolivian state in 2008. With the exception of TCO Tapiete, all these territorial claims contain important gas reserves. Perhaps not coincidentally, all besides TCO Tapiete remain in a legally fragmented state following the TCO land-titling process, which remains incomplete (see Figure 3). That is, collective Indigenous land rights are not held over a contiguous area (the claimed TCO territory), but comprise a patchwork of isolated fragments of less-productive land that are interspersed with privately titled or unresolved property claims. These ambivalent land-titling outcomes are partly a result of inherent weaknesses in the INRA Law (which prioritises private property claims in TCOs provided they demonstrate productive land use), but also reflect the political dynamics of the titling process, which saw sustained opposition from non-Indigenous land claimants and the influence of hydrocarbon interests.Footnote 48

Figure 3. Map Showing Outcomes of TCO Land Titling in the Bolivian Chaco

Source: Adapted with permission from Fundación TIERRA, Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos en Bolivia: Entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama (La Paz: Fundación TIERRA, 2011), p. 125. Previously printed in Anthias, Limits to Decolonization, p. 2.

This lack of territorial integrity and unfinished nature of the TCO titling process means that TCOs in Tarija are unable to gain formal Indigenous autonomy. The 2009 Constitution states that Indigenous autonomy is ‘based on consolidated [i.e. titled] Indigenous territories and those in process, once consolidated’,Footnote 49 while the 2013 Ley de Unidades Territoriales (Law of Territorial Units) explicitly prohibits the recognition of Indigenous peasant autonomy in Indigenous territories that are not continuous.Footnote 50 Indigenous peoples in Gran Chaco are also unable to achieve autonomy at a municipal level, as this requires winning a municipal referendum – something that is impossible to achieve given their status as demographic minorities within their respective municipalities. This set of legal obstacles to achieving formal Indigenous autonomy provides important context for understanding why Indigenous peoples have sought participation in regional autonomy.

As noted above, early iterations of regional autonomy were based on a regional economic-development vision that overlooked the presence of Indigenous peoples entirely. This is unsurprising given that, during the early 1980s, many Indigenous families in the Chaco remained trapped in relations of semi-slavery on non-Indigenous haciendas, where they were subject to violent forms of discipline and lacked basic citizenship rights. As chaqueño politician Horacio Sánchez admitted, the protagonists of regional autonomy looked to local peasants, teachers and workers’ federations for support:

Only on some occasions did they request – and this is painful – the help of Indigenous peoples. But almost never, as far as I remember, did they involve them, with an equitable and protagonist role, in the negotiations, in the demands. When they needed strength to block that bridge […] they put some Indigenous people there to help – they gave them coca, alcohol, and that was it. But involve them – let's see, what ideas do you have? – no … They didn't recognise them much because they didn't reclaim their rights.Footnote 51

Nevertheless, following Indigenous mobilisation in the late 1980s, the Asamblea del Pueblo Guaraní (Guaraní People's Assembly, APG), established in 1987, led the way in challenging the 1989 Pacto de Quebracho and its proposal of a ‘tenth department’ in the Chaco, which encompassed and erased Guaraní ancestral territories. Instead, they proposed the establishment of an autonomous Guaraní Nation extending over the entire Chaco region of Bolivia – a proposal that struck fear into national as well as departmental and regional elites.

Given these precedents, it is not surprising that Chaco Indigenous people continued to express suspicion about Gran Chaco's regional autonomy project and its advance under the MAS. An event I attended on ‘chaqueño peasant identity’ in 2011 was illustrative. Organised by a local research non-governmental organisation (NGO) in Tarija City, the event gave voice to Indigenous peoples’ deep distrust regarding the way in which regional identity was being used for political ends in ways that marginalised them. As one Guaraní leader commented: ‘Why are they only talking about peasant identity and not about Indigenous peoples?’Footnote 52 The Weenhayek participant observed: ‘They always want to make us disappear’ and noted that ‘autonomy isn't new, it's what we did many years ago’. A female Guaraní leader expressed a similar sentiment, arguing: ‘When they put forward the issue of autonomy, we already had it. Our ancestors weren't professionals but they had a lot of knowledge that stayed inside of us.’ She claimed that the real objective of the event was to enlist Indigenous peoples’ support for a non-Indigenous autonomy project, noting ‘we continue to be betrayed, especially with the territorial issue in the Chaco’.

Despite these evident tensions, Indigenous peoples have ultimately gained significant representation within the Chaco's new regional institutions. Gran Chaco's Autonomy Statute stipulates that Indigenous peoples will have one assembly member for each of the three Indigenous peoples, who are to be elected ‘according to their own usos y costumbres [norms and procedures]’.Footnote 53 This mirrors the broader structures of Bolivia's plurinational state; the 2009 Constitution and 2009 Ley Régimen Electoral Transitorio (Transitory Electoral Regime Law) created special Indigenous circumscriptions within the Chamber of Deputies, Plurinational Legislative Assembly and departmental legislative assemblies. Given the small size of Gran Chaco's regional assembly, the results of this special representation are striking: out of a total of nine asambleístas (assembly members), three are Indigenous, with the remaining six elected by popular vote. Indigenous representatives also argued that their presence in the regional assembly was a result of their demands for representation, following their participation in mobilisations instigated by chaqueño leaders in 2001, 2004 and 2008 (see below).

Alongside this political representation, the Chaco's Regional Autonomy Statute, Regional Development Plan and Operating Regulations include various articles recognising Indigenous languages, symbols, practices and political concepts. For example, the regulations state:

The ethical principles on which service to the Chaco people is based are: YEYORA, OHUUMIN OCHOUMET [freedom], MBOREREKUA, LAIKYWEEJ ¡IIHI¡ [solidarity and generosity], IYAMBAE, OWEEN OT¡AMSEK [being without an owner, free of oneself], MBOROAIU, YOPARAREKO, INA¡AWHAWULHKIA [feeling of love, friendship, brotherhood, equality] YOMBOETE, YOPOEPI, OJWAAWALHIAJ IHII [respect for others and oneself, reciprocity] MBAEYEKOU, INALA¡NHUUNNEEN [harmony with oneself, equilibrium].Footnote 54

The preamble of the Autonomy Statute includes the following passage:

On this land, several racial groups coexisted, originating from the Pampa and its passage to the Amazon, fighting with courage to defend their habitat and their right to land and life, and finally fighting against European conquerors and republican colonists, giving rise to the historic mixing of the Chaco people and its strongest Indigenous peoples that transcended the history, such as the Guaraní, Weenhayek and Tapiete.Footnote 55

This passage is reminiscent of the discourse of mestizaje that underpinned the foundation of Latin American republics, in which the mixing of Indigenous and Spanish blood – combined with an appropriation of Indigenous histories of anti-colonial resistance – served to give legitimacy to a national independence project led by criollo elites. Arguably, these examples amount to little more than an instrumental co-option of indigeneity to serve an elite-led project for capturing gas rents. It is unclear how Indigenous ‘ethical principles’ will translate into political practices and priorities. Nevertheless, the presence of three elected Indigenous representatives within the regional assembly represents a watershed in a region where Indigenous peoples were only in the 1990s recognised as rights-bearing citizens. The question arises: What, in practice, are Indigenous assembly members able to achieve? The following vignette provides some insights.

Inside the Autonomous Regional Assembly

The Asamblea Regional del Chaco is housed in a large concrete building (see Figure 4) on the outskirts of Caraparí, the smallest of the Gran Chaco's three urban centres and the site of important gas wells. When I first visited the assembly building in 2016, I was astounded by its sheer size. One of many ‘white elephants’ that have sprung up during the Chaco's gas bonanza,Footnote 56 it appeared jarring against the backdrop of the lush green mountains of Aguaragüe, a national park co-managed by the Guaraní.Footnote 57 The assembly's exterior is decorated with the Bolivian crest, the regional autonomy shield (see Figure 5), a wire illustration of a gas well, and a curious mural depicting hydrocarbon infrastructure and environmental destruction. Inside, wide corridors of mainly empty offices surround a giant concrete courtyard, containing what can only be described as a large paddling pool. As I toured the expanse of the building with Mauricio, the appointed advisor to the Guaraní assembly member, we contemplated possible uses for the pool; he suggested that the legislators could hold ‘aquatic sessions’ with towels, swimming trunks and piña coladas. Despite its opulent design, the building's deterioration over the past few years has become evident; the roof is now decayed and mouldy, and the concrete is starting to look aged. Already, the assembly is beginning to look like a relic from the gas boom.

Figure 4. The Autonomous Regional Assembly of the Chaco Tarijeño

Source: Photo by author.

Figure 5. The Official Shield of the Autonomous Regional Government of the Chaco Tarijeño

Note: This shield is reproduced on the regional assembly's documents and building.

Source: Agencia Chaqueña de Información, available at http://achi-yba.blogspot.com/2012/08/los-simbolos-regionales-del-gran-chaco.html, last access 2 Dec. 2021.

During my first visit in 2016, I spent several days in the Indigenous peoples’ bench of the regional assembly, chatting with Mauricio, the Guaraní asambleísta Jorge, and other assembly employees. Outside and around the Indigenous offices, colourful posters show scenes from rural Indigenous life and declare the assembly's commitment to Indigenous cultures of the Chaco (see Figure 6). During this visit, Mauricio was optimistic about what Indigenous peoples could achieve based on their demographic weight within the assembly. Because the remaining six assembly members were split equally between the ruling MAS party and the right-wing opposition party Camino al Cambio (Path to Change, CC), Mauricio felt they were in a strong position to make demands in exchange for their political support. Given the assembly's limited powers, such demands were necessarily limited to inclusion within public spending plans and regional planning processes. Still, following a history of Indigenous exclusion from public institutions and minimal state investment in rural Indigenous communities, this was significant.

Figure 6. Poster Hanging by Indigenous Peoples’ Bench of Regional Assembly

Note: This poster states that the assembly is ‘committed to the cultures and the preservation of our beautiful Chaco land’.

Source: Photo by author.

However, Guaraní asambleísta Jorge did not appear to share Mauricio's optimism. Hailing from a rural community in Caraparí municipality, I have known Jorge since 2008, when he was an articulate leader at the forefront of a new territorial claim. Sitting behind his desk in his plush new office, he looked weary and dejected. He admitted that most of his work in the assembly was not directly related to the demands of Guaraní communities. Indeed, many of his activities related to ensuring the continuing existence of the regional assembly, which remained in a precarious state pending the popular referendum approving the Regional Autonomy Statute later that year. When I asked about the Guaraní's current priorities within the assembly, he mentioned a series of construction projects, many of which were paralysed due to lack of funds. However, he reflected that the Guaraní would not really benefit from these roads anyway, given that they were mainly subsistence producers. Meanwhile, he noted that Guaraní communities in Caraparí municipality had still received nothing from the departmental cash transfer programme PROSOL (Programa Solidario) – a result of the fact they have still not obtained legal personhood as Indigenous communities (discussed below).

When I returned to Caraparí in 2017, the regional assembly had acquired a somewhat more permanent status, following a regional referendum on 20 November 2016, in which the Regional Autonomy Statute received a ‘yes’ vote of 72.4 per cent. This assured the regional assembly's future and set in motion the establishment of the executive branch of the regional government. I met Mauricio in the central plaza of Caraparí and we walked together towards the assembly. He paused at a measured distance from the building to update me on the internal politics of the Indigenous bench. He explained that, while the three Indigenous legislators initially had a political pact with the ruling MAS party, this had broken down. The Guaraní representative Jorge had remained aligned with the MAS, the Weenhayek representative had made a pact with the right-wing party, while the Tapiete representative had been removed from his position owing to an administrative technicality – namely, his failure to formally ‘resign’ from his post before being re-elected by his people.Footnote 58 As such, while the Indigenous representatives made up three out of nine legislators, they had remained divided by rival party interests, whose promises often remained unfulfilled. As Mauricio concluded: ‘The Indigenous peoples have always been an instrument to benefit interest groups and their political priorities. And unfortunately, the three [Indigenous representatives] have not been able to act in a coordinated way to demand the fulfilment of promises. And part of these promises is that effective and significant resources arrive to the three [Indigenous] peoples.’Footnote 59

The susceptibility of Indigenous representatives to division and co-option by rival party interests should not be taken as evidence of the colonial stereotype of the easily bribable Indian. The Guaraní, in particular, have a long tradition of forging temporary alliances with multiple factions as a means of evading control by karai (non-Indigenous) political institutions – something that has been called ‘Guaraní diplomacy’.Footnote 60 These divisions must also be read in the context of the MAS government's efforts to consolidate its political hegemony, in ways that have narrowed the room for manoeuvre for Indigenous activists in Bolivia. Increasingly, political opponents have found themselves silenced, imprisoned, exiled or excluded from access to public institutions and funds.Footnote 61 This exacerbates the dilemmas faced by Indigenous representatives in the Chaco.

Jorge, the Guaraní representative in the assembly, reminded me that the Guaraní have always maintained a non-aligned position vis-à-vis political parties – a position I have heard repeated many times in Guaraní assemblies. He described how the need to make political alliances with the two main political parties compromised the value Guaraní place on an independent ‘autonomous’ stance.Footnote 62 It had also caused division between the three Indigenous legislators, he explained, with offers from political parties undermining Indigenous people's sense of having their own political vision. Jorge admitted feeling unable to achieve much in his role, aside from securing a few small projects for Guaraní communities in exchange for his political support for one of the main parties. He also complained that Guaraní communities did not put forward their demands or take advantage of his position – an indication of the distancing from Indigenous communities that often follows absorption of Indigenous leaders into the state. Despite these challenges, however, he expressed optimism. Once the executive branch of the Chaco regional government was established, Indigenous legislators would be able to approve all fiscal policies of the provincial government, he noted, providing further opportunities to direct state resources towards rural Indigenous communities.

Notwithstanding this possibility, Jorge admitted that his position did not allow him to address the most pressing problem for Guaraní communities in Caraparí municipality: access and rights to land, which was beyond the assembly's competencies. While the question of Indigenous land claims remains unresolved throughout the Bolivian Chaco, these communities’ situation is particularly acute. Excluded from earlier processes of Indigenous mobilisation in the 1980s and 1990, these Guaraní communities only recently formed their own Indigenous organisation, the APG Karaparí, presenting a TCO claim to the Bolivian state in 2006. In 2008, an investigation by the International Labour Organization (ILO) confirmed the continuing existence of forced-labour practices in the municipality, which are known locally as empatronamiento (a form of debt peonage).

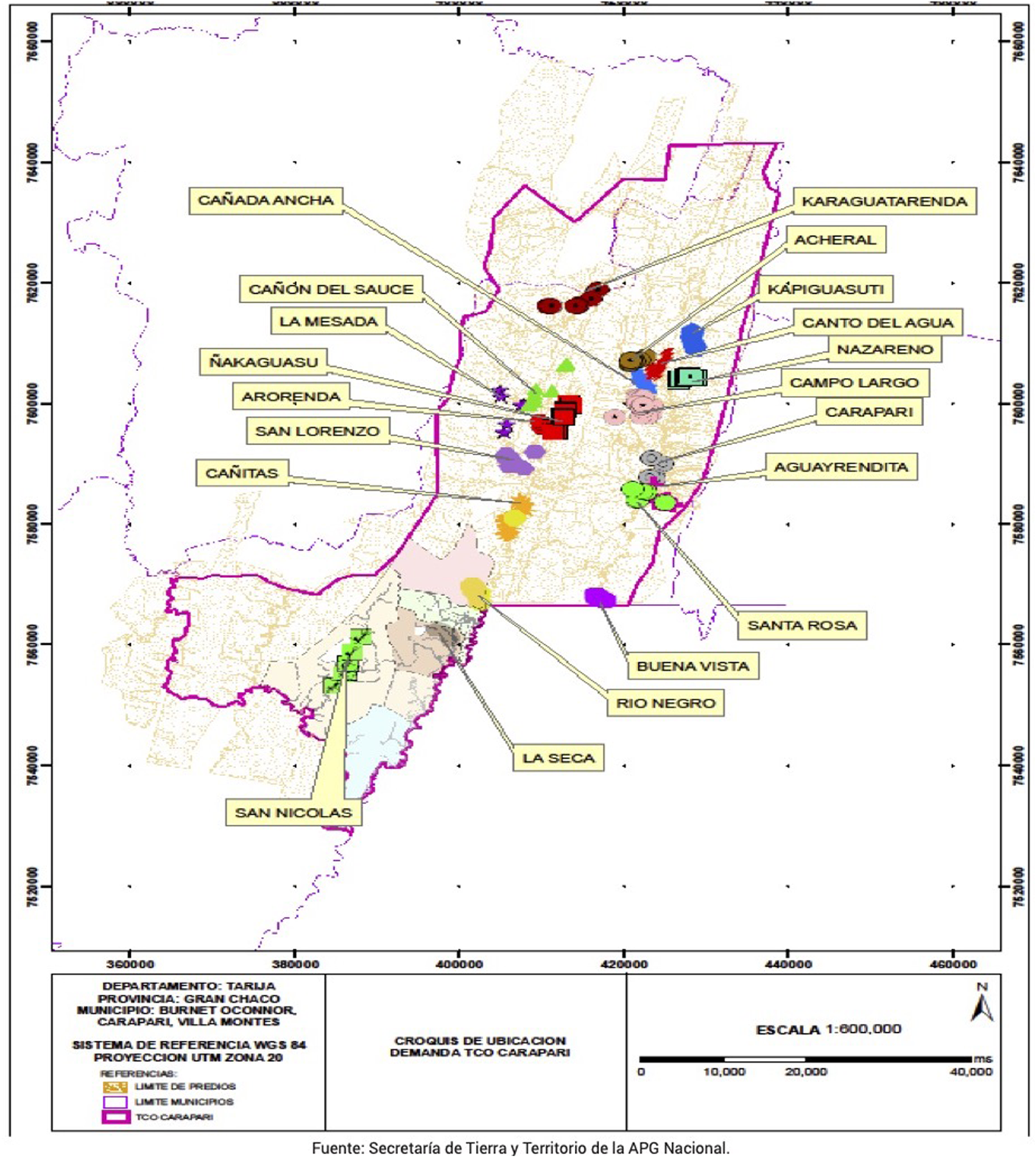

Under the 2009 Constitution and revised INRA agrarian reform law of 2008, the discovery of such practices is grounds for state expropriation of private land to award to Indigenous claimants. However, this has not occurred in TCO Karaparí. To date, the MAS government has only recognised one of 22 communities included in the territorial claim (see Figure 7), subjecting the remainder to a process of individual land titling that has privileged non-Indigenous land claimants and ‘invisibilised’ Guaraní communities, many of which have found themselves trapped within the boundaries of private properties. While sustained opposition of local peasant organisations aligned with the MAS has been a major obstacle, many Guaraní believe the state's unwillingness to recognise their territorial claim is due to the existence of important gas reserves in the territory. Meanwhile, the state's refusal to grant these communities legal personhood means that hydrocarbon development continues to unfold without prior consultation.Footnote 63

Figure 7. Guaraní Communities Included in the Karaparí TCO Claim

Note: At the date of publication, only Kápiguasuti had been granted legal personhood as an Indigenous community.

Source: Secretariat of Land and Territory of the APG, reprinted in Defensoría del Pueblo, ‘Estado de situación del ejercicio del derecho a la tierra y al territorio por parte de las familias guaraníes en el Municipio de Caraparí’ (La Paz: Defensoría del Pueblo, 2014), p. 24.

The land situation also affects communities’ ability to access state development projects. Jorge gave the example of Cañon Ancho, where the Guaraní community live inside the property of their patrón, who presented himself as the leader of the community and succeeded in getting funding for cattle-ranching projects from the municipality and provincial government. While these projects are of no benefit to Guaraní families, Jorge described how people remained silent owing to the patrón's continuing power in the community. While there is not space here for a detailed discussion of these broader challenges of decolonising territory, it is notable that Indigenous representation within the Autonomous Regional Assembly does little to resolve the ongoing forms of territorial and environmental dispossession faced by Indigenous communities in the Chaco.

Indigenous representatives were quick to acknowledge these limitations. Yet, they also described how occupying the state formed part of long-term Indigenous agendas for decolonisation and resource justice. A Guaraní−Spanish translator within the regional assembly critiqued the rigid laws and statutes of the assembly, but also argued that the presence of Indigenous peoples in the assembly was ‘opening up a path’ for future generations, which was ‘not going to open on its own’.Footnote 64 A departmental Indigenous legislator argued that participation in state institutions was a means of addressing long-standing Indigenous grievances regarding the unequal distribution of economic benefits and environmental costs of extraction, and of advancing Indigenous development priorities – from budgets for bilingual teachers to changing the school calendar to accommodate the fishing season. He explained:

We're hopeful about regional autonomy because […] it's better that our authorities are from the region; an authority that is self-governing, manages its own resources, is an authority that knows the needs that we have … As Indigenous peoples, we could take advantage of this space to generate and work on projects that benefit our people, not depend anymore on people from here [Tarija City].Footnote 65

As this demonstrates, despite facing ongoing forms of racialised exclusion within the Chaco, some Indigenous leaders share the critique of departmental centralism that underpinned demands for regional autonomy. This leader also saw Indigenous participation in the Chaco's regional government as a just recompense for the sacrifices Indigenous peoples had made in social mobilisations in defence of regional autonomy. As he put it:

Regional autonomy has been an achievement, it's been a struggle that has not only been by the people of the city. Guaraní, Tapiete, Weenhayek have also been part of this struggle […] the famous 45 per cent that they've achieved for the Chaco, we also fought for that conquest, and the criollos – we say criollo for the people of the city – don't recognise us. That is, they don't recognise the sacrifice that the Indigenous person also made to achieve something for their benefit […] it's like the Chaco War, you know that [the dominant narrative of] the Chaco War doesn't mention a single Indigenous person, but our ancestors tell us another history, which the karai are reluctant to recognise. Worse still if we want to [gain credit for] this [regional] autonomy process. Why? Because this will affect […] it will affect their pocket [their money]. The resources they manage they don't want the Indigenous person to manage, you see. That's the total reality that exists today.Footnote 66

As this passage reveals, Indigenous participation in regional autonomy gains meaning in the context of a long struggle for postcolonial recognition. Throughout history, Chaco Indigenous peoples’ erasure from regional and national historiography has legitimised their exclusion from political and economic power. Indigenous demands for a seat at the table of regional autonomy can be read as an act of resistance to these ongoing acts of erasure. As the final sentences of the quotation imply, such recognition is also viewed as connected to ongoing struggles over the distribution of gas rents. Concretely, Indigenous representatives have been fighting for a fixed 15 per cent share of the regional assembly's annual income to be allocated directly to Indigenous organisations – a proposal that would represent a significant shift in regional power relations and the territoriality of regional governance, albeit without departing from an extractivist development model.

The above testimonies make clear that, for all the ambivalences of regional autonomy, Indigenous representatives are not simply political instruments of elite interests. Rather, by occupying spaces in the pluri-extractivist state, they engage in acts of strategic manoeuvring and resistance against a long history of racialised rule.Footnote 67 As another Indigenous departmental legislator argued:

I think [participation in the regional assembly] is worth a lot, it's our grain of sand that we've put there, because in this way Indigenous peoples are being taken into account, that we're also capable of occupying a space, a political space – we feel capable, because before they said ‘you, no, you don't know, so stay there’, but now the same people are realising that Indigenous peoples are capable.Footnote 68

Defending Gran Chaco's 45 Per Cent?

What these ‘grains of sand’ will achieve over the coming years and decades remains to be seen. The steady decline of Gran Chaco's gas reserves, combined with shifting geographies of hydrocarbon extraction, mean that the future of regional autonomy is far from certain. During my 2017 fieldwork, the beginning of seismic testing in Tariquía National Park (located in Tarija Department but outside of Gran Chaco Province) was already generating heated debates about whether Gran Chaco's 45 per cent share of departmental royalties could be justified. Politicians in neighbouring O'Connor Province were leading calls for a more just distribution among provinces, while rural communities had mobilised in a march on the regional capital to demand a new ‘8 per cent law’ allocating a fixed share of departmental hydrocarbon royalties to non-Chaco municipalities.

On 11 May 2017, I attended a meeting in the Municipal Council of Yacuiba, whose purpose was to devise strategies to defend the Chaco's 45 per cent in the face of these various challenges. The invitation letter sent to Indigenous representatives described the event as ‘a meeting of COORDINATION,Footnote 69 which will touch on themes of great importance for the Chaco's population, such as: Law 3038 – 45 Per Cent of Hydrocarbon Royalties; treatment of the Fiscal Pact and 8 Per Cent Transference Law; various points’. Various local politicians gave speeches, arguing that the 45 per cent was part of Gran Chaco's ‘patrimony’ as an entidad territorial autónoma (autonomous territorial entity) under the 2009 Constitution, and that it was recognised in law and in the Regional Autonomy Statute, and was therefore ‘untouchable’. One man proposed the creation of ‘20 padlocks’ through different articles of law to ensure the 45 per cent could not be challenged.

Tellingly, Indigenous representatives provided more critical interventions. Most compelling was the speech by the Weenhayek departmental representative. He began by greeting the audience in Weenhayek, reminding everyone that, under the 2009 Constitution, everyone had the right to express themselves in their own language. He said it was an honour to be invited and at a moment when ‘unity calls us’ in Gran Chaco. While Indigenous peoples wanted to be part of this, however, he reminded participants that ‘this unity shouldn't be only for the issue of resources’.Footnote 70 There were also natural disasters – recent drought and declining fish stocks had decimated Indigenous communities – which also called for regional unity. He noted that during the past two years, departmental Indigenous assembly members had not received a single visit, suggestion or paper from the Chaco's regional authorities. Despite this, he and other Indigenous representatives had been called to defend Gran Chaco's 45 per cent. He emphasised: ‘We [Indigenous peoples] have suffered for a very long time amidst the boom of Tarija Department, of Gran Chaco’, inviting the audience to visit Indigenous communities, which ‘had not received benefits that have an impact in our TCO, our territory’. He noted that Indigenous peoples ‘have been shouting and complaining for years’ about not receiving their share of benefits, even though the Constitution recognises that attention should be given to the demands of communities directly affected by hydrocarbon development. Indigenous peoples were aware of this, he said, because ‘the part that suffers is not the city – the environmental impacts are suffered by us, inside our territory’.

As this makes clear, Indigenous support for regional autonomy is not unconditional, nor is it uncritical. While there are clear limits on what Indigenous representatives are able to achieve within an extractivist state, Indigenous representatives use their presence within these political spaces to voice prescient critiques of broader structures of colonial power, environmental dispossession and resource injustice. It is in transforming these broader geographies of territory and power – not only in pluralising political institutions – that the challenge of decolonisation lies.

It is also worth noting that Chaco Indigenous peoples have abandoned their hopes for alternative, Indigenous-led visions of autonomy and plurinationalism. Indeed, the possibilities of pursuing the two established routes to Indigenous autonomy – Indigenous peasant territories and Indigenous municipalities – remain a frequent topic of conversation among Indigenous organisations. Indigenous peoples are also engaged in creative strategies for consolidating their territorial claims, such as the physical occupation of state lands (which provides a pragmatic alternative to the ongoing struggle for rights to privately claimed properties within TCO land claims). As such, regional autonomy is just one of multiple arenas in which Indigenous peoples in the Chaco are seeking to strategically navigate competing notions of territory and sovereignty in defence of their own agendas of territory and self-determination.Footnote 71

Conclusion

While plurinationalism and extractivism have previously been seen as competing projects within Bolivia's ‘process of change’, this article has revealed how they are becoming articulated in local processes of state formation in the Chaco. The successful campaign for regional autonomy in Gran Chaco highlights how local actors rework the relationship between extraction, territory and citizenship ‘from the ground up’ to produce new forms of territoriality. Bolivia's plurinational state provides a new context for such articulations, which risk displacing and subordinating Indigenous peoples’ own visions of autonomy and plurinationalism. A focus on these local dynamics of state formation enriches debates on extractivism, moving beyond a focus on state-led dispossession and place-based resistance to reveal how Indigenous decolonial projects are also compelled to navigate competing subnational claims for territory and resource sovereignty.

Of course, this is not only a story about local state formation. It is also an account of the consolidation of central state power by the MAS government, which has used subnational demands for autonomy and fiscal decentralisation to weaken political opposition in the lowlands. The success of regional autonomy in Gran Chaco reflects the bargaining power of local elites in the context of broader disputes over political authority, nature and nation.Footnote 72 This sheds important light on the limits to decolonisation within an extractivist development model. Despite overseeing the most radical constitution in Bolivia's history, the MAS government's reliance on subsoil resources located in Indigenous territories has led to the formation of historically familiar alliances of sovereignty with non-Indigenous landowning elites in the lowlands, which have been prioritised over Indigenous demands for territory and autonomy.

Despite these ambivalences, this article has revealed how Indigenous peoples have demanded representation within Gran Chaco's regional government and are seeking to use this as a means to advance their own political agendas – such as inclusion within regional planning processes, the allocation of state funds to Indigenous development priorities, and the breaking down of historic structures of racialised rule. I have argued that strategic navigation of elite-dominated political spaces is a necessary part of Indigenous decolonial politics in Tarija, and does not signal an abandonment of broader Indigenous agendas of territory and self-determination. Still, the accounts of Indigenous representatives highlight the limits of these political spaces, where colonial power structures, bureaucratic obstacles and clientelistic party politics limit Indigenous representatives’ ability to centre Indigenous development priorities. Of course, these dynamics are nothing new; clientelism, corporatism, corruption and racism are long-standing features of state institutions in Tarija Department. In that sense, pluri-extractivism may be a vehicle for continuity and ‘gatopardismo’ as much as it is a new configuration of power.Footnote 73 The ongoing dispossession and abandonment suffered by rural Indigenous communities in the Chaco sheds further critical light on the limits of Indigenous representation within an extractivist state.

In the context of shifting hydrocarbon geographies and declining gas fields, the future of Gran Chaco's regional autonomy is uncertain. Competing subnational claims to autonomy and gas rents raise questions about what alternative articulations of pluri-extractivism may emerge over the coming years in Tarija Department and beyond. How Indigenous peoples will navigate these shifting territorial and resource politics, and to what extent they will succeed in recentring and consolidating their own visions of Indigenous autonomy within a plurinational state, remains to be seen.

Acknowledgements

This research benefitted from funding from the Independent Research Fund Denmark Project: LEAKS: Resource Enclaves and Unintended Flows in Latin America, and from the European Research Council (ERC) Grant: State Formation through the Local Production of Property and Citizenship (Ares (2015)2785650 – ERC-2014-AdG – 662770-Local State). I am extremely grateful to the three anonymous reviewers, to JLAS editors and to Sarah A. Radcliffe and Lauren Martin for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.