1. Introduction

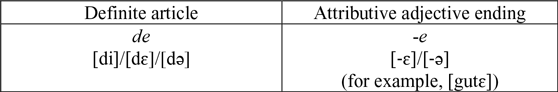

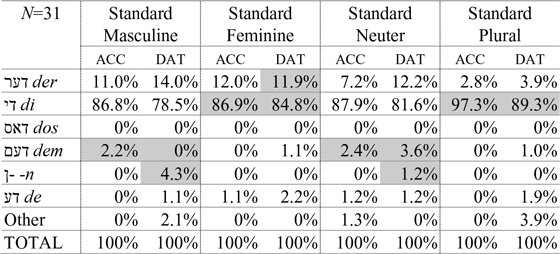

The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that the post-War generations of Yiddish speakers in the main Hasidic communities worldwide (Israel, the New York area, Montreal, and Antwerp) have complete absence of morphological case and gender from their grammar. Most of the speakers in our study use an invariable determiner pronounced as /dɛ/ or /di/, whereas the earlier case and gender suffixes on attributive adjectives have been reanalyzed as a single attributive marker, /ɛ/. The paper builds upon our research on the present-day Yiddish of Hasidic speakers in London’s Stamford Hill (Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a), which found that this variety of Yiddish had completely lost morphological case and gender within two generations, starting with speakers who acquired their language in the immediate post-War period. In this respect, our findings resemble those of Krogh (Reference Krogh, Aptroot, Gal-Ed, Gruschka and Neuberg2012, Reference Krogh, Elmentaler and Hundt2015, Reference Krogh2018), Assouline (Reference Assouline, Aptroot and Hansen2014), and Sadock & Masor (Reference Sadock and Masor2018), who have conducted research on the morphological case and gender of Hasidic Yiddish speakers in New York and Israel. However, while these authors interpret their findings as evidence of case syncretism or “extensive loss of gender and case morphology” (Krogh Reference Krogh, Elmentaler and Hundt2015:383), our elicited spoken and written data point to a much more far-ranging phenomenon: the total loss of morphological case and gender and its complete absence from full noun phrases in the present-day language. As argued in our work on Stamford Hill Hasidic Yiddish (Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a), this variety has undergone a significant and rapid change since World War II, as Hasidic speakers and writers of Yiddish who came of age in the pre- and inter-War period have the same case and gender system as their non-Hasidic counterparts and roughly the same tripartite system as that found in Standard Yiddish.Footnote 1 This pre-World War II system is exemplified in table 1 below for the sake of comparison.Footnote 2

Table 1. Nominal case and gender marking in Standard Yiddish (after Kahn Reference Kahn, Kahn and Aaron2017:675–676).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In section 2, we provide a historical background of contemporary Hasidic Yiddish, including its relation to the most relevant pre-War dialects of the language. Section 3 outlines the present study, describing the participants and the design of the research tasks. Section 4 summarizes the findings of each task, while section 5 provides discussion and analysis of them. Section 6 concludes.

2. Historical Background

Hasidism emerged as a spiritual movement within Judaism in the late 18th century in an area corresponding to present-day Ukraine. Over the course of the 19th century, the movement proliferated and gained a large following among Eastern European Jews. Hasidic rebbes, or spiritual leaders, became the heads of dynasties generally named after the locations in which they were founded; well-known dynasties include Belz, Karlin, Lubavitch (also known as Chabad), Satmar, and Vizhnitz. Like other Eastern European Jews more broadly, adherents of the Hasidic movement were overwhelmingly speakers of Eastern Yiddish, which can be divided into three chief dialects: Northeastern, Mideastern, and Southeastern.Footnote 4 Most of the Hasidic dynasties were located within the Mideastern and Southeastern Yiddish dialect regions (corresponding to present-day Poland, Hungary, Romania, and Ukraine), and hence their adherents mainly spoke Mideastern and Southeastern Yiddish.

By contrast, Hasidism was less prevalent in the Northeastern Yiddish dialect regions (corresponding to present-day Lithuania, Latvia, and Belarus). Yiddish speakers in the Northeastern dialect area were more typically associated with a non-Hasidic Haredi variety of Jewish educa-tion and practice, and as such, the Yiddish term Litvish, meaning ‘Lithuanian’, has come to be commonly used with specific reference to non-Hasidic Haredi Jews, in addition to the more general geographical meaning.Footnote 5 However, some Hasidic dynasties (most prominently Chabad and Karlin) were based in the Northeastern dialect region, and hence adherents of those groups have traditionally spoken Northeastern Yiddish. Nevertheless, despite their Lithuanian geographical origin, such Hasidic speakers of Northeastern Yiddish may not identify themselves as Litvish because of the strong association between this term and non-Hasidic Haredi Judaism.

Until World War II, the Yiddish spoken by adherents of the Hasidic movement resembled that of non-Hasidic Jews with respect to its morphological composition: Hasidic and non-Hasidic users of Yiddish employed the same tripartite gender and case system (with the exception of Northeastern Yiddish, which has only two noun genders; see Jacobs Reference Jacobs1990). This system was similar to the one in the standard form of Yiddish provided in table 1 above (see Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a for further discussion of case and gender in historical varieties). However, there were some instances of case syncretisms between accusative and dative in the spoken dialects, especially for nouns with nonhuman referents (Wolf Reference Wolf, Marvin, Ravid and Weinreich1969), which could be seen as the starting point for later developments (see also Krogh Reference Krogh, Aptroot, Gal-Ed, Gruschka and Neuberg2012 for the same hypothesis).

The Holocaust and concomitant dispersal of the surviving Hasidic communities from their pre-War Eastern European centers led not only to a catastrophic decrease in the numbers of Hasidic Yiddish speakers, but also to a rapid realignment, whereby survivors from different geographical locations and traditional Hasidic groups (as well as non-Hasidic Haredi, or strictly Orthodox, Jews) were brought together in new locations, chiefly Israel, Antwerp, the New York area, London’s Stamford Hill, and Montreal. The Hasidic population of these new Yiddish-speaking Haredi centers was generally much larger than its non-Hasidic Haredi counterpart, and there was greater interaction between the two groups as they became increasingly united, in contrast to the majority secular societies (see Heilman & Skolnik Reference Heilman and Skolnik2007). This situation led to substantial dialect mixing. Furthermore, native Yiddish speakers were joined by an influx of L2 speakers, who became part of these newly established primarily Hasidic communities. In our view, this final factor was crucial to the rapid development of the language over the subsequent several decades.

In this paper, we claim that this unusual and rapid geographical and sociolinguistic transformation resulted in a complete loss of the pre-War morphological case and gender system, to the extent that contemporary speakers have a total absence of these morphological elements. Having demonstrated this to be the situation with respect to the Yiddish of London’s Stamford Hill Hasidic community (see Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a), in the present paper we evaluate the speech and writing in multigenerational Yiddish-speaking communities in the other main Hasidic centers worldwide. We demonstrate that the same process has taken place in the language of these communities as well, so that it is now possible to speak of a global variety of Yiddish used by Haredi, and chiefly Hasidic, speakers which completely lacks morphological noun case and gender.Footnote 6 We refer to this variety of Yiddish as Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

Our analysis of morphological case and gender in the contemporary Hasidic Yiddish of speakers between the ages of 18 and 87 (median: 28 years; one third of participants over 40) is based on interviews with 40 native Yiddish speakers who were born and raised in Haredi communities worldwide.Footnote 7 We worked with 13 Israeli participants (three female) between the ages of 20 and 87. The Israeli participants grew up in communities such as Bnei Brak, Ashdod, and in and around Jerusalem. An additional 22 participants (nine female) between the ages of 18 and 72 are from the New York area (including a range of Haredi neighborhoods in Brooklyn, as well as several Haredi communities in upstate New York). In addition, three participants (two female) are from the Montreal area and are between the ages of 18 and early 40s, and two participants (both male) are from Antwerp and are between the ages of 20 and 30.Footnote 8

Our participants do not differentiate varieties of Yiddish based on the historical dialects (for example, Northeastern, Mideastern or South-eastern) and rarely do so in any geographical terms (for example, Polish, Hungarian, Russian, Lithuanian, American, Israeli). We therefore do not do so here. Rather, most speakers identify as speaking Hasidic Yiddish, and often differentiate between those who speak vos (that is, with a vowel profile most closely matching that of the traditional Northeastern dialect and who therefore pronounce the word וואס ‘what’ as [vɔs]), and those who speak vus (that is, with a vowel profile most closely matching that of traditional Mideastern and Southeastern dialects and who therefore pronounce the word וואס ‘what’ as [vʊs]). Those who speak vos include speakers from Chabad, speakers of a dialect known as Yerushalmer, or Jerusalem Yiddish, as well as those non-Hasidic Haredi speakers who refer to themselves as “Litvish Yiddish speakers”.Footnote 9 Those who speak vus comprise most other Hasidic affiliations, including Belz, Dushinsky, Karlin, Pupa, Satmar, Skver, Tosh, Tsanz, Vizhnitz, Vizhnits-Monsey and so-called klal Hasidish, that is, nonspecific/general Hasidic. It is important to note also that while some Hasidic sects are associated with one pronunciation or the other (for example, Satmar and Belz are associated with vus, while Chabad and Karlin are associated with vos), individual speakers inside those communities might differ. Our sample includes 26 speakers of vus (12 female), 10 speakers of vos (2 female), and 4 who speak a mixed phonological variety (usually one where וואס ‘what’ is pronounced [vʊs] but, for example, דריי ‘three’ is pronounced [draı] rather than [draː]). The speakers of the mixed variety often attributed this fact to their exposure to both vos and vus during their formative years, whether in the family, in educational institutions, or in the wider community. Five of the vos speakers are from the New York area and five from Israel.

Our interviews with participants reveal that there is significant mobility between geographical communities of speakers and even between Haredi sects. Fewer than half of our participants grew up in the same location as both of their parents (for example, Israel, the New York area, etc.). In most cases, one or both parents grew up in a different geographical location from the participant. The participants’ grand-parents come from a much wider variety of locations, including Romania, Hungary, Switzerland, Poland, the United Kingdom, and Israel. Most of the participants come from multigenerational Yiddish-speaking backgrounds, but a small number are first-generation (fewer than five speakers) or second-generation speakers (fewer than 10 speakers), with their parents or grandparents having acquired the language as their L2. Likewise, most of the participants come from multigenerational Hasidic backgrounds, but in some cases one or more of the parents or grandparents came from a non-Hasidic Haredi background, and in a relatively large minority of cases the Hasidic affiliation of either the participant or the participant’s family changed over the years (for instance, as a result of marriage or changes in the preferences of the head of the family).

Interview data indicate that there is much less mobility between Chabad and other Hasidic communities than between non-Chabad Hasidic communities. This may be due, at least in part, to the somewhat different orientation of Chabad, which places a great emphasis on outreach activities among nonobservant Jews and therefore has consider-able involvement in secular society. In contrast, most other Hasidic groups tend to interact much less with nonobservant Jews (see Wodziński Reference Wodziński2018, especially 214–217). Similarly, there is relatively little mobility between non-Hasidic Haredi and Hasidic communities, due to the traditional religious and historical differences between these groups, and because the former (like Chabad) generally have more interaction with secular and non-Jewish society (Heilman & Skolnik Reference Heilman and Skolnik2007:349).

All of our participants were raised in Yiddish-speaking homes and were largely educated in Yiddish, particularly in the early years. For teenagers, there was a gender distinction in schooling, whereby girls tended to receive more secular instruction in coterritorial languages than boys. The Israeli participants received secular instruction in Hebrew, with the New York and Montreal participants receiving it in English, and the Antwerp participants receiving it in Flemish or French.Footnote 10 In addition, the Montreal participants received some instruction in French as a Second Language, which, however, was rather limited as they typically reported being much less comfortable using French than English.

Instruction in religious subjects was typically received in Yiddish by both genders. Boys attended yeshivas, or Talmudic academies, whose curriculum focused on the classical religious Jewish texts with an emphasis on the Babylonian Talmud, composed largely in Aramaic, and its commentaries, composed largely in Hebrew. However, the language of instruction and discussion in the yeshivas is typically Yiddish, with increasing use of loshn koydesh (the traditional Yiddish term for premodern Hebrew) in the later years. Many of the participants use Yiddish on a regular basis in their current everyday life, including with their spouse, children, and friends. Others, by contrast, now only employ it only on occasion (for example, when talking with one or both of their parents). Some speakers also employ English, Modern Hebrew, and/or French (depending on the location) on a regular basis due to employment outside of the community. All participants are comfortable reading and writing in Yiddish, though not all of them regularly employ the language in these ways.

3.2. Description of Tasks

Our examination of the status of morphological case and gender in Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish is based on elicited spoken and written data. The tasks used to elicit the data are described below.Footnote 11

Task 1 was a sequence of open biographical questions asked in Yiddish about each participant’s cultural and linguistic background, including their Hasidic affiliation, family, schooling, and attitudes toward Yiddish and its use in everyday contexts. This task allowed the researchers to gather a corpus of free speech, including the participants’ use of case and gender.

Task 2 was an online translation task comprising a short text provided in both English and Hebrew and controlled for case, gender, definiteness, animacy, and the presence of attributive adjectives. Partici-pants could choose the version they were most comfortable with and were asked to read the text quietly sentence-by-sentence and then translate each sentence into Yiddish out loud. The task allowed the researchers to record the participants’ phonological realization of determiners and adjectival endings, which in turn made it possible to assess their use of morphological gender and case in a controlled narrative context as opposed to the free speech of task 1.

Task 3 was an image-based writing task, whereby participants were shown 33 pictures relating to eight singular and three plural nouns for each of the three genders (33 nouns in total). Some of the nouns were taken from the Swadesh list (Swadesh Reference Swadesh, Sherzer and Chicago1971:283), while the remainder were chosen because they are highly frequent, highly imageable, and reflect a mix of the Germanic, Semitic—in this case, Hebrew rather than Aramaic—and Slavonic lexical components of Yiddish. The inclusion of the Hebrew vocabulary was particularly important as the Israeli Yiddish speakers are generally bilingual in Modern Hebrew, which has morpho-logical noun gender. Therefore, we wanted to be able to determine whether or not the Israeli participants had a better sense of the gender of Semitic nouns than of other Yiddish nouns, due to their familiarity with gender in Modern Hebrew.Footnote 12 Each image was accompanied by a ד, the first letter of all forms of the Yiddish definite article and representing /d/, followed by a blank line. Participants were asked to fill in the blank line by completing the definite article and writing the word for the image. The task was designed to prompt the participants to provide the “dictionary” (that is, nominative) form of the definite article along with each noun, allowing the researchers to analyze their use of gender morphology separately from considerations of case and number.

Task 4 was a dictation task in which carrier sentences containing the same 33 nouns as in task 3 were read out to the participants in Yiddish by a speaker of Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish, who was using the invariable determiner de and the attributive marker -e, the characteristic spoken form for most Hasidic Yiddish speakers. Each noun appeared in three different grammatical environments, which in pre-War and Standard Yiddish would require different case markings—nominative, accusative or dative, preceded by a definite article and accompanied by an attributive adjective. Participants were asked to “write down the sentences that they hear,” with no further instruction given on the form of the definite article or morphological ending on the adjective. This task allowed the researchers to ascertain whether or not participants varied the form of the definite article according to the noun phrase’s role in the sentence (that is, whether or not they used different case morphology). Comparison with the answers provided in task 3 allowed us to gain further insight into the consistency of gender morphology. The task was administered in a Latin square design so as not to overburden the participants: Each noun was presented to some of the participants, but each participant saw a third of the nouns (equally distributed for gender).

Task 5 was a copy-editing task, whereby participants were presented with a paragraph written in Yiddish. The text was selected from a Hasidic Yiddish newspaper publication, but it was adjusted to include a balanced number of nouns in the three Standard Yiddish cases and genders, as well as forms that do not conform to Standard Yiddish.Footnote 13 In addition, distractor errors in the form of typographical errors and phonological spelling were included, such as שיל shil for שול shul ‘synagogue’. The participants were told that the article was taken from a Stamford Hill newspaper and reflected Yiddish usage there. The partici-pants’ task was to find any mistakes in the text or point out anything they would say or write differently. The point of this task was to investigate our participants’ sensitivity to different, sometimes inconsistent, case or gender morphology.

Task 6 was a judgment task, whereby participants were shown groups of four or five sentences, with each sentence containing a noun from a gender-balanced subset of the 33 nouns used in tasks 3 and 4. Each group of sentences contained one tested noun in subject, object, or prepositional object position. The group of sentences were minimal sets, varying only in the case form of the definite article, די di, דער der, דאס dos, and דעםdem, and a fifth form, for example, מיטן mitn from מיט דעם mit dem ‘with the’, where the contracted preposition + determiner form was available. For each sentence, participants were asked to indicate which version(s) of the determiner they found acceptable or unaccept-able, or if they were unsure. In a language with morphological case or gender marking, participants would be expected to accept one correct form of the definite article and reject the rest, but in a language without morphological case or gender, more variation or uncertainty would be expected. This task therefore provided a direct insight into the participants’ knowledge of and attitudes toward morphological case and gender. Comparison with the answers provided in tasks 3 and 4 allowed for further analysis of the participants’ strategies in selecting determiner and adjective forms.

The participants were presented with the tasks in the order listed above. Arranging the tasks in this order allowed us to begin with the most open task and to end with the forced-choice one, in order to avoid influencing the participants’ answers as much as possible. In addition to the completion of the tasks, the interviews also included periods of metalinguistic and sociolinguistic discussion, which serve to supplement our analysis of the data collected.

4. Findings

4.1. Task 1: Free Speech

The overwhelming majority of the 40 participants who completed task 1 consistently employed a single definite article, which we uniformly transcribe as de. For most speakers from the Chabad background and for those who identify themselves as speaking Litvish (that is, Lithuanian non-Hasidic Haredi) or Yerushalmer (that is, Jerusalem Yiddish; all of these communities traditionally spoke a Northeastern variety of the language), this form was pronounced as [di], but all other speakers (the majority of our participants) used the novel form pronounced as [dɛ] or [dǝ]. The novel form [dɛ] (and its optional reduced variant [dǝ]) has also been documented as the only definite article employed by Stamford Hill Hasidic Yiddish speakers in Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a.

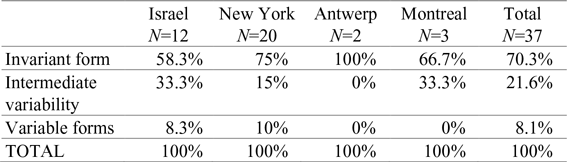

Along with the definite article de almost all participants employed a single form of attributive adjectives, marked by the suffix [‑ɛ] or the reduced variant [‑ǝ]. This variant is henceforth transcribed as -e, because Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish spoken in some geographical commu-nities have unstressed vowel reduction, as in, for instance,צוריק tsurik [tsǝrik], זיך zikh [zǝkh], so the pronunciation involving schwa is the result of a general phonological rule. This suffix was the marker of feminine nominative and accusative attributive adjectives in pre-War and Standard varieties of Yiddish, but it has been reanalyzed as an attributive marker in Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish (see Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a). Like the definite article, this attributive marker was attested in the speech of participants from all the communities under investigation. Accordingly, the Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish definite article and adjective paradigms are shown in table 2.

Table 2. Definite article and attributive adjective endings in spoken Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish.

The de …-e pattern applies to all nouns, both singular and plural, regardless of their gender and case in pre-War and Standard Yiddish. These results are in agreement with our data from Stamford Hill speakers (see Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a) and in stark contrast to the pre-World War II situation as described above (see table 1) and in more detail in Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a.

4.2. Task 2: Oral Translation

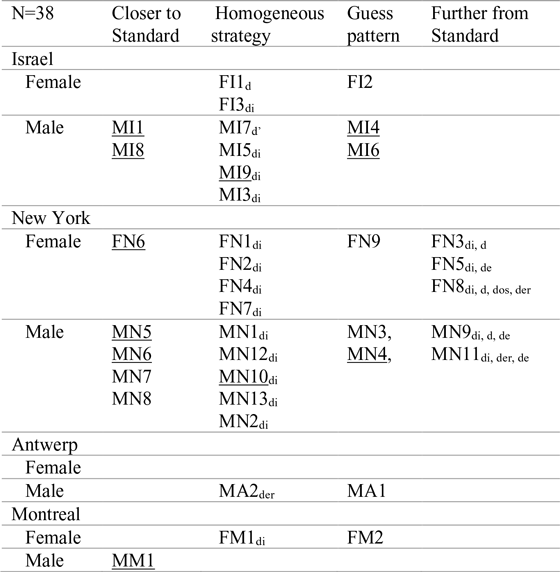

There was more variability in the results of task 2 compared to those of task 1. While in task 1 participants very rarely used forms other than de …-e, the same was only true for around 70% of the 37 participants who completed task 2. These participants continued to use a single invariant form of the determiner either throughout or in the overwhelming majority of cases, with a small handful of exceptions. Approximately 20% (a total of eight speakers) used an invariant form throughout, but they also used other forms with some regularity. About 8% (a total of three speakers) used forms other than de …-e regularly throughout their translation. This pattern holds for all geographical communities. These results are summarized in table 3.

Table 3. Proportion of participants providing invariant, variable, and intermediately variable forms, task 2.

Age, gender, and geographical location did not seem to be good predictors of the participants’ behavior in task 2.Footnote 14 Speakers using invariant forms ranged in age from 18 to over 80, came from all communities represented in our sample, and were equally represented in each gender. Similarly, speakers who used a variety of forms either occasionally or more regularly (rows 2 and 3 in table 3) ranged from around 30 to their mid-70s and were represented in three of the four communities in our sample, as well as each gender. Speakers from traditionally Northeastern Yiddish-speaking communities did not differ in their behavior from other speakers. Rather, the greatest predictor of use of a variety of definite determiner forms was active engagement with and interest in the Yiddish language as adults. This interest took a number of forms: involvement with secular Yiddish-speaking organi-zations such as theatres and Yiddish teaching, study of aspects of the grammar of the language (for example, etymology), and regular consumption of Yiddish-language written media. This type of speaker can be contrasted with those who reported using Yiddish as their vernacular but not having a particular interest in it from a linguistic or literary perspective.

However, none of the speakers in our sample exhibited standard-like case or gender morphology, or patterns of morphology similar to that of pre-War varieties of Yiddish. Even those speakers who used the fewest de …-e forms (and therefore the most variant forms) were sometimes inconsistent in the gender they assigned to a given noun or made use of mixed agreement patterns. Furthermore, although the three speakers who used the largest number of variant forms were all from traditionally Northeastern-speaking communities (one was Litvish, one Chabad, and one speaks Jerusalem Yiddish), each made use of adjectival forms with a null ending. Such forms are associated with the neuter gender (traditionally only in indefinite neuter noun phrases) and are therefore unexpected in the speech of Northeastern Yiddish speakers, which traditionally had only masculine and feminine grammatical genders.

The variant forms used included set phrases such as in a kleyn shtetl ‘in a small shtetl’ or in der heym ‘at home’ and contracted prepositional forms such as nokhn raykhn vetshere ‘after the abundant dinner’ and nokhn shabesdike sude ‘after the Sabbath feast’. The latter was also often used with nouns that are feminine in Standard Yiddish. Sometimes the semantic gender of a noun denoting a human male was reflected, as in der zun ‘the son’ or der man un di froy ‘the man and the wife’. In some cases, the masculine dative form of the article was used, as in betn fun dem oreme mentsh ‘to ask the poor man’, nebn dem oyvn ‘next to the oven’, and oyf dem shvartsn hitl ‘at the black hat’. As above, however, this form is also found with Standard Yiddish feminine nouns, as in, for instance, tsu dem altn froy ‘to the old woman’.

As we demonstrate below, use of variant forms in task 2 did not predict standard-like performance in the other tasks. Rather, we suggest that the participants were compelled to use variable forms in a more formal, story-telling context. This idea is supported by the fact that many participants who used an invariant form in the rest of their translation nonetheless translated the scene-setting phrase ‘in a small village’ (akin to ‘once upon a time’ in English) as in a kleyn derfl, which lacks the attributive adjective marker and is what would be expected in Standard Yiddish and many pre-War varieties. This analysis explains why participants who used a variety of forms relatively often in task 2 used them much less in the free speech of task 1. It also explains why they were inconsistent in gender assignment for particular nouns, both within task 1 and across other tasks: Awareness of the existence of forms other than de …-e does not necessarily correspond to an awareness of their standard use as specific case and/or gender markers.Footnote 15

Taken together, the results of task 1 and task 2 indicate an absence of true case or gender morphology on full nominals from the spoken language of our participants. The definite determiner appears almost exclusively as the novel form [dɛ] (or [di] for vos speakers), while attributive endings are uniformly marked with the attributive marker [-ɛ] (or [‑ǝ] for speakers with unstressed vowel reduction). Some fossilized forms reflecting earlier case and gender morphology persist in the language, but they are not used consistently or productively in everyday speech and may represent a more formal, story-telling register. Speakers who take an active interest in the Yiddish language were more likely to use the story-telling register involving variable gender and case forms.

4.3. Task 3: Picture Naming in Writing

Task 3 was completed by 38 participants. They were presented with a series of pictures and asked to write the name of the object in each picture using a noun in the nominative case with a determiner. The large majority of the participants assigned only masculine and feminine gender to the nouns, with their choices matching Standard Yiddish 45.8% of the time. The neuter determiner דאס dos was hardly used at all, and if the participants were randomly using דער der and די di across all nouns, we would expect their performance to be standard-like 50% of the time. Thus, overall performance on task 3 was roughly at chance, suggesting that the participants did not use different forms of the definite determiner as markers of morphological gender.

Table 4 summarizes the results of task 3 across all participants. It demonstrates that the participants’ use of particular definite article forms does not reflect morphological gender assignment in Standard Yiddish. Rather, a general pattern, irrespective of the noun’s gender in Standard Yiddish, is that speakers used דאס dos or דעם dem very infrequently; they used innovative forms such as דע de or ד׳ d’ about 10% of the time; and they overused די di and underused דער der.

Table 4. Distribution of definite determiner forms with nouns in each of the three Standard Yiddish genders and plurals, task 3.Footnote 17

Some other interesting patterns emerge, if one looks at the breakdown of the results for speaker gender, as shown in table 5. Here one sees that women generally used דער der less than men.Footnote 18 Women also used more innovative forms compared to men. One way to explain this pattern is to suggest that women prefer to represent the invariable spoken form of the article with a written form that is phonologically most faithful, without attempting to utilize the variety of forms available in pre-War and Standard Yiddish. At least some men showed the opposite tendency: They preferred to use not only די di but also דער der and to a lesser extent דאס dos and דעם dem; they also made use of innovative forms somewhat less, and therefore were less faithful to the spoken pronunciation.

The breakdown of the data for the different locations revealed less pronounced differences. A table is provided for the interested reader in Appendix. The only small difference was that New York speakers in general dispreferred innovative forms and tended to use די di instead. These observations might suggest that Israeli speakers are more innovative in their written usage compared to New Yorkers.

From the individual participant data two patterns emerge. The first one we refer to as the homogeneous pattern, and the second one the mixed pattern. Participants who followed the homogeneous pattern did not attempt to use the three article forms דער der, די di, or דאס dos. Rather, they did not differentiate the form of the definite determiner for any noun in its citation form. The choice of the definite determiner form appears to be phonological: These participants tried to match the phonological shape of the spoken /dɛ/ or /di/ with a familiar written form. In task 3, 50% of the participants fit the homogeneous pattern, with most of those usingדי di as their preferred written form of the definite determiner. These results are similar to the results of task 2, where approximately two thirds of the participants used an invariant form of the determiner in an oral translation. Not surprisingly, given the breakdown of the results by gender in table 5, most women show the homogeneous pattern. Also—again in line with the breakdown of the results by location in table 3—no New York speaker used an innovative form of the article as their only form, while several Israeli speakers did.

These results are summarized in table 6. Participants’ codes in this table and throughout the paper follow the following convention. The first letter refers to the speaker’s gender F=female, M=male; the second letter refers to the speaker’s location I=Israel, N=New York area, M= Montreal area, A=Antwerp; the following digits identify the speaker uniquely in their gender/location group. For instance, FI1 refers to No1 Israeli Female Speaker. Additional relevant information may be provided in a subscript. In table 6, the subscript identifies the relevant forms of the article the speaker used in task 3. Those participants who gave a variety of forms in task 2 more than a handful of times are underlined.

Table 5. The distribution of definite determiner forms used with nouns in each of the three Standard Yiddish genders and plurals in task 3, by speaker gender.

Table 6. Patterns of responses broken down by speaker gender and location, task 3.

Participants exhibiting the mixed pattern can be subdivided into three groups: those whose use of case and gender forms is furthest from pre-War and Standard varieties, those operating roughly at chance, and those whose use of these forms is closest to pre-War and Standard varieties. Partici-pants whose responses were least standard-like made use of novel determiner forms such as דע de and ד d. Those operating roughly at chance used a mix of דער der and די di forms alongside a smaller number of דאס dos and even דעם dem forms, but often favored one form and used others more sparingly.Footnote 19 Those whose responses were most standard-like used a variety of forms in more equal proportion and used them in standard-like contexts more often than would be expected at chance.

No participant used pre-War or Standard Yiddish forms 100% of the time. The participant whose responses were most standard-like used standard masculine and feminine forms 80% of the time.Footnote 20 By contrast, speakers of languages with morphological case and/or gender can be expected to make speech errors in this morphology at a rate of about 1%–4% (Luzzatti & de Bleser 1999, Schmid Reference Schmid2002). At the same time, it is noteworthy that greater use of a variety of forms in task 2 largely correlated with more standard-like performance in task 3: Nine out of eleven participants who used a non-די di form more than a handful of times in task 2 were in the mixed groups in task 3. Conversely, three quarters of the participants who used most standard-like forms in task 3 used a variety of forms of the determiner with at least some regularity in task 2. Yet participants were not consistent in their use of gender morphology for particular nouns across the two tasks, and individual participants who showed the most standard-like results in task 3 assigned the same nouns different gender in the two tasks. This pattern may not be taken as an indication of a morphological gender system; but it does show that speakers relatively consistently fall into either the mixed or the homogeneous group across tasks.

Once again, the strongest predictor of standard-like responses in task 3 was not age, gender, phonological profile, or geographical location, but interest in the Yiddish language. Such an interest appears to lead to an awareness of the existence of a variety of definite determiner forms (acquired through engagement with written sources, particularly historical and non-Hasidic ones) without an awareness of their use as morphological gender markers. We suggest that this is because these speakers lack the concept of morphological gender in their mental grammars of Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish.

The findings reported here were confirmed by metalinguistic discussions with participants who said they did not know the difference between the various historical forms of the determiner and were not sure which form to use in the written tasks. For example, FI2 commented that she would always use the (novel) form /dɛ/ in speech, and that she did not know which form to select for each lexical item in task 3. This remark explains why FI2 selected different determiner forms in task 3: While she did vary her choice of determiner for the 33 nouns, she did so not out of an innate familiarity with the gender of each noun, but rather out of an awareness that different variants of the determiner existed in the written language and should be used. As her inconsistent usage reveals, she does not have a knowledge of an actual gender (or case) morphology system regulating the use of these forms. Similarly, even those participants whose results were most standard-like in task 3 did not seem to be aware that Yiddish might have grammatical gender or had it at some point in its history. MI8, for instance, is a speaker of Jerusalem Yiddish who also speaks Modern Hebrew, a language with morpho-logical gender. He expressed surprise at the idea that nouns in Yiddish might have grammatical gender, despite being comfortable with the concept in Modern Hebrew.

4.4. Task 4: Dictation

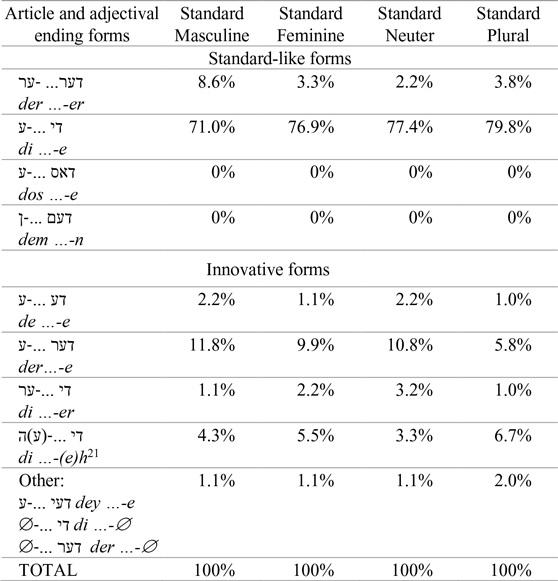

Task 4, a dictation task, allowed participants much more flexibility in their responses. Participants were asked to “write down what they hear” as a speaker of Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish dictated full sentences containing definite noun phrases with an attributive adjective. The results reflect this greater flexibility, with participants providing a much wider range of responses and a larger number of innovative forms (that is, forms that did not exist in pre-War varieties and in Standard Yiddish) compared to the previous tasks. In fact, participants used a total of 20 different determiner/adjective combinations, of which 15 were innovative.

Table 7 summarizes the results of task 4 for the nominative case. Across the three standard genders and plurals, the proportion of each form is approximately the same. Between 70%–80% of responses in the nominative case contained די …‑ע di …-e forms regardless of the noun’s gender or number in pre-War and Standard varieties of Yiddish. Between 5%–12% of responses contained the innovative form דער …‑ע der…-e across all standard genders and in the plural. Less than 10% of responses contained דער …‑ער der …-er (expected in Standard Yiddish masculine nominative and feminine dative) and a similar proportion contained די …‑(ע)ה di …-(e)h (an innovative form using a Hebrew-like spelling variant of די …‑ע di…-e). Again, these numbers hold across all standard genders and the plural. Remaining responses were split between the innovative forms דע …‑ע de …-e (<5%), די …‑ער di …-er (<5%), and other forms including demonstrative determiners and forms lacking an attributive adjective marker (<5% altogether). The Standard Yiddish neuter nominative דאס …‑ע dos …-e and masculine (and neuter) accusative/dative דעם …‑ן dem …-n forms were never used. These results are comparable to those of task 3, summarized in table 4 above, and strongly suggest that morphological gender plays no role in participants’ selection of definite determiner and attributive adjective forms. Table 7 shows the distribution of the articles and adjectival endings used with modified masculine, feminine, neuter, and plural nouns in the nominative case in Standard Yiddish.

The results of task 4 also demonstrate that participants do not perceive a link between the form of the definite determiner and that of the attributive adjective. While they are by far most likely to provide matching די …‑ע di …-e forms, they apparently do so because this is perceived to be the closest written form to the novel spoken determiner /di/ or /dɛ/ and the attributive marker /-ɛ/. However, they are more likely to provide mismatching forms such as דער …‑ע der …-e than the matching form דער …‑ער der …-er. Indeed, overall, participants wrote attributive adjectives with an ending matching the pronunciation /-ɛ/ (that is, ‑ע -e or ‑(ע)ה ‑(e)h) more than 10 times more often than attributive adjectives ending in either ‑ער -er or -∅. These results show that, regardless of the form of the definite determiner, speakers of Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish mark attributive adjectives almost uniformly with an ‑ע -e ending, corresponding to the spoken attributive marker /-ɛ/.

For this reason (and for the sake of clarity), we present the results of task 4 for the accusative and dative cases in table 8 according to the form of the definite determiner only. These results show that participants overwhelmingly providedדי di forms for plurals, although some participants provided דער der, דע de, and even דעם dem forms in the plural as well, especially for dative plurals. For singular nouns, the proportion of each determiner form is roughly stable across cases and Standard Yiddish morphological gender, with די di being used around 80% of the time, דער der between 5% and 15% of the time, דעם dem less than 5% of the time, and דע de less than 3% of the time. No participants provided any דאס dos forms in any case or gender. Table 8 shows the distribution of determiner forms used with modified masculine, feminine, neuter, and plural nouns in the accusative case and prepositional dative case in Standard Yiddish.

Table 7. Distribution of endings used with modified nouns in the nominative case, N=31, task 4.

Table 8. Distribution of determiner forms used with modified nouns in the accusative case and prepositional dative case, task 4.

These results confirm the participants’ overwhelming preference for די di as an invariant definite determiner in all cases and genders, as it is used between five and ten times more often than any other form.Footnote 22 דעם dem is used somewhat more often with nouns in the accusative and dative cases (in all genders) than in the nominative, but the effect is very small. Speakers did not provide the דאס dos form in any case or gender. For many speakers, די di appears to be the preferred invariant definite determiner because it is closest to their pronunciation of that form. As table 9 reveals, a strong preference for using די di with all nouns irrespective of case and gender was especially true for women and to a lesser extent for Israeli speakers irrespective of gender. The table shows a breakdown of different determiner forms used with modified nouns of all Standard Yiddish genders in all cases by speaker gender and location.

Table 9. Breakdown of determiner forms used with modified nouns in Standard Yiddish by speaker gender and location, task 4.

The speakers who provided forms other than די di appear to be somewhat aware of the correlation between variant determiner forms and singular noun number: Speakers provided a smaller variety of forms and fewer variant forms for plural nouns. This correlation is not perfect, however, as some participants nonetheless provided forms other than די di, including innovative forms, for plural nouns. Overall, the results demonstrate that participants have no association between the definite determiner form and morphological case or gender, suggesting that their mental grammars of Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish lack such concepts.

Comparing task 4 to previous tasks, one can tell that individual participants were not necessarily consistent across all tasks. While the vast majority of those who used invariant forms in tasks 2 and 3 tended also to do so in task 4, some introduced variant forms in this task. In the other direction, however, there was less consistency. About half of the participants who used variant forms in task 2 or task 3 used a single invariant form in task 4. Furthermore, even the participants whose performance was most standard-like in tasks 2 and 3 were not always consistent in the morphological gender they assigned to particular nouns, both across tasks and, occasionally, within task 4. These participants also made use of mixed morphological forms such as די …‑ער di …-er, which are unexpected in pre-War and Standard varieties of Yiddish. This pattern is inconsistent with the idea that these speakers have morpho-logical case and gender, and rather suggest that speakers are aware of the existence of a variety of definite determiner and attributive adjective forms but are unaware of their use as morphological case and gender markers.

4.5. Task 5: Copyediting

In task 5, participants were asked to correct a written text, originally derived from the Stamford Hill Tribune. This text had been altered to ensure a roughly equal number of masculine, feminine, and neuter nouns in each of the three cases, as well as roughly equal numbers of standard-like and non-standard-like definite determiner and attributive adjective forms, including mismatched morphological endings. Overall, the text included 16 non-standard-like forms.

On average, participants made 3.3 corrections to case or gender forms in task 5, with a range of 0–13 and a median of 2. Four out of 31 participants made no corrections to case and gender forms, while every participant corrected some spelling or other distractor errors. Two participants made more than eight corrections. Many corrections did not make the text more standard-like, particularly the large number of corrections of attributive adjectives to an ‑ע ‑e form that did not match the accompanying definite determiner. Several participants corrected standard-like forms to innovative or non-standard-like forms. These results are summarized in table 10.

Table 10. Number of corrections of case and gender morphology provided in task 5, by participant.

A number of corrections involved harmonizing mismatched case and gender morphology, although these were not always in the direction of pre-War or Standard varieties of Yiddish. Furthermore, many corrections introduced mismatched morphology, for instance, where the attributive adjective was corrected to an ‑ע -e form regardless of the form of the definite determiner. Some participants also offered two options for a particular correction; for example, one participant corrected פון דער נייעם בארג fun der nayem barg ‘from the.er new-n mountain’ to פון דער נייעם אדער די נייע בארג fun der nayem oder di naye barg ‘from the.er new-n or the.i new-e mountain’. Participants also occasionally introduced novel forms, for instance, correcting אינעם וואנט inem vant ‘in.the.n wall’ to אין ד וואנט in d vant ‘in the.∅ wall’. Most participants also ignored inconsistencies in the gender agreement on particular adjectives.

The participants making the most corrections in task 5 (FN6 and MM1, as well as MN5, MN6, and MN8) used variable forms with some regularity in at least two of tasks 2, 3, and 4. At the same time, many of these participants provided invariant forms in at least one of tasks 2, 3, and 4. Thus, all of these participants show inconsistent use of case and gender morphology across the four tasks as well as in specific lexical items. What all the participants in this group have in common is an active interest in the Yiddish language, which in task 5 is reflected in a more proactive approach to copyediting.

Overall, these results are consistent with those of earlier tasks in suggesting that participants do not have a concept of morphological case or gender in their mental grammars. In particular, these results demon-strate that most participants do not consider inconsistent use of case or gender morphology to be an error that needs correcting, whereas those who do make more case- and gender-related corrections nevertheless do not exhibit a grammar with a more robust case and gender system.

4.6. Task 6: Written Judgments

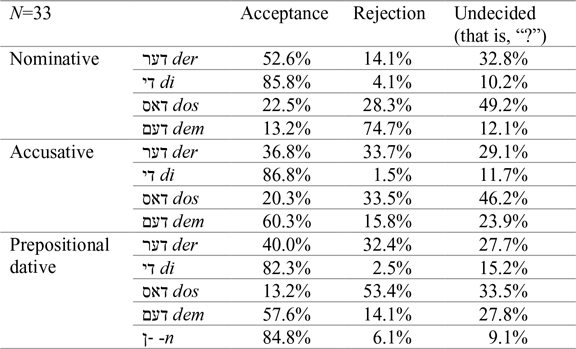

In task 6, participants were presented with 18 sets of four to five sentences each. The sentences in each set acted as carriers for one of nine nouns targeted in tasks 3 and 4, with the noun appearing in the subject, object, or prepositional object position. In each set, the target noun had a different form of the determiner (that is, דער der, די di, דאס dos, דעם dem) in each sentence. The participants were asked to indicate for each sentence in the set which of the determiner forms they would or would not use; which one sounded natural or unnatural to them, or whether or not they were unsure. For dative nouns, which were always objects of a preposition, an additional option was provided, namely, the contracted form preposition + definite determiner. In Standard Yiddish, there is only one prescriptively correct answer per set for subjects and objects and up to two for prepositional objects (that is, אויף דעם oyf dem and the contraction אויפן oyfn are both expected for ‘on the’ in masculine and neuter datives). Accordingly, native speakers of a language with morphological case or gender would be expected to be relatively certain in their responses.

Overall, participants accepted standard-like forms 61.4% of the time (that is, slightly better than chance), with individual participants ranging from 22.7% to 87.8%. However, participants rejected non-standard-like forms only 28.4% of the time (range: 16.4%–40.4%). These results suggest that they are more permissive than speakers of pre-War and Standard varieties would be, as they tend not to reject forms that diverge from Standard and pre-War Yiddish use. Furthermore, participants were undecided 25.3% of the time (range: 21.1%–29.2%), which does not resemble what would be expected in a language with morphological case or gender. These results are summarized in table 11: It shows average proportion of acceptance, rejection, and undecided judgments matching Standard Yiddish gender and case; it also shows a range of proportions for all gender and case combinations.

Table 11. Proportion of acceptance, rejection, and undecided judgments; range of proportions for gender and case combinations.

Table 12 provides another perspective on these findings: It shows the distribution of participants’ responses with respect to modified nouns that matched pre-War and Standard Yiddish gender assignment, irrespective of case. If Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish had lost only case and not gender, participants might be expected to consistently choose the form of the definite determiner according to morphological gender only and disregard the noun’s case. The results suggest that this is not so. Proportions of acceptance, rejection, and “not sure” responses for each of the determiner forms are stable across the three Standard Yiddish genders. Participants accept די di at a very high rate (80%–90%) and reject or are unsure about דאס dos at a relatively high rate (30%–40% and 40–45%, respectively). The contracted form of prepositional datives is very frequently accepted (80%–90%), regardless of noun gender. דער der and דעם dem fall somewhere in between these extremes.

Table 12. Participants’ responses for modified nouns matching Standard Yiddish gender assignment, task 6.

The participants’ responses, therefore, do not match the pattern that would be expected in a language with morphological gender. The participants allowed a range of forms and exhibited relatively high levels of uncertainty. These results are consistent with the findings in previous tasks in suggesting that participants recognize די di as an invariant definite determiner, but other forms are also accepted, albeit to a lesser degree. These findings also demonstrate that the contracted form of the preposition + definite determiner is widely permitted in all genders, with acceptability levels similar to די di, suggesting that this form has become fossilized when used with a relevant preposition and is no longer associated with particular morphological genders. Furthermore, the findings confirm a dispreference for דאס dos, which is also consistent with the results of previous tasks.

Table 13 summarizes participants’ responses by noun case, regardless of noun gender; it shows the distribution of participants’ responses with respect to modified nouns that matched pre-War and Standard Yiddish case assignment, irrespective of gender. If Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish had lost morphological gender and retained morphological case, one might expect one form of the determiner to be associated with a particular morphological case. Again, the results suggest that this is not the case. Participants accept די di at a high rate (80%–90%) in all case contexts and reject or are unsure about דאס dos at a lesser but still noticeable rate (at approximately 30%–55% and 35%–50%, respectively). Where available (that is, with prepositional objects), participants demonstrate a strong acceptance rate for the contracted form of the determiner (85%). Participants accept דער der marginally more in the nominative case than they do in the accusative or dative and accept דעם dem much more in the accusative and dative than they do in the nominative. However, acceptance rates for both דער der and דעם dem are no higher than 60% in any case, and 28% of participants are not sure about using דעם dem in the dative case, in addition to the 14% who reject it outright.

Table 13. Participants’ responses for modified nouns matching Standard Yiddish case assignment, irrespective of gender, task 6.

Again, these results are not expected in a language that has morphological case. Participants are more permissive and report higher levels of uncertainty than what would be expected in such a language. די di is used as an invariant definite determiner regardless of noun case, although contracted forms of the determiner are accepted alongside it in the dative case. While there is a higher acceptance rate for דער der in the nominative case and, conversely, a higher acceptance rate for דעם dem in the accusative and dative, these forms are accepted alongside די di rather than instead of it. Rather than suggesting that Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish has a productive system of morphological case, the results suggest that awareness of דער der and דעם dem as case forms is vestigial, along the lines of the who/whom distinction in English (see, for example, Schneider Reference Schneider, Svartvik and Wekker1992, Lasnik & Sobin Reference Lasnik and Sobin2000, Boyland Reference Boyland, Bybee and Hopper2001, Schepps Reference Schepps2010). In contrast, the contracted form of the determiner appears to be a fossilized form accepted in all prepositional dative contexts regardless of noun gender.

However, the overall results obscure a noteworthy effect of speaker gender.Footnote 23 Table 14 presents the same results as table 13 but broken down by speaker gender. Here it is evident that, while men and women behave the same way in some respects, in others their behavior varies. Men and women accept, reject, and are unsure about די di at similar rates across all cases, and they also behave similarly with respect to the contracted preposition + determiner form in the dative. However, men are much more likely than women to accept דער der in all three cases. For their part, women reject דער der at a much higher rate than men in all three cases. Men are more likely than women to accept דעם dem in the accusative and dative cases. However, men and women reject דעם dem at very similar rates in all three cases. Unlike דער der, which women reject at a higher rate than men, דעם dem is a source of uncertainty for women, as they are more often unsure than men about whether or not it sounds natural in the accusative and dative. Furthermore, men reject דאס dos at a higher rate than women in all cases, while women are more often unsure than men about using דאס dos. Table 14 outlines the participants’ responses with respect to modified nouns that matched pre-War and Standard Yiddish case assignment, irrespective of the noun gender. The results are broken down by speaker gender.

It might seem surprising that those speakers who were most likely to use variant forms in previous tasks—and who therefore might be expected to most closely approximate pre-War and Standard varieties of Yiddish—were nonetheless very permissive in task 6. Conversely, the least permissive speakers in task 6 consistently used invariant forms in earlier tasks. However, these results are not, in fact surprising, if our analysis thus far is correct. Speakers from the homogeneous group are expected to accept only those forms that approximate the spoken form of the definite article, just as they produce such forms in writing. At the same time, if speakers in the mixed group use a variety of forms not because they have a productive system of morphological case and gender but because they are familiar with these forms and know that they are often used in writing, they are expected to accept a range of forms when presented with alternatives.

Table 14. Participants’ responses for modified nouns matching Standard Yiddish case assignment irrespective of noun gender.

Overall, we find that women are more innovative in their choice of determiner: They especially prefer a single, invariant form and either reject or are unsure about forms that men accept. In contrast, men accept a wider range of forms across all cases and are more conservative in that they have a somewhat stronger association between דער der in the nominative and דעם dem in the accusative and dative. The latter is also true for Israeli speakers irrespective of their gender, which would identify them as more conservative speakers for case assignment. These patterns are in line with general sociolinguistic tendencies, which show that women are innovators of linguistic change (Labov Reference Labov1990). Furthermore, women’s choice of determiner seems to be more strongly associated with the phonology of the spoken definite determiner, whereas men make greater use of forms that differ in their pronunciation from the spoken determiner. However, regardless of speaker gender, determiner choice does not seem to be determined by morphological case or gender.

5. Discussion

To sum up, all of our participants appear to lack a morphological gender or case-marking system in their mental grammars. Some speakers are aware that historically there were four article forms in Yiddish, that is, דער der, די di, דאס dos, and דעם dem, as well as matching adjectival agreement endings ‑ער ‑er, ‑ע -e, and ‑ן ‑n; they produced a variety of definite determiner and attributive adjective forms in both written tasks 3 and 4, and in oral storytelling tasks 1 and 2, albeit in a way that is very different from Standard Yiddish. In contrast, other speakers used one form of the article consistently, which they perceived as phonologically closest to the spoken /dɛ/ or /di/ form of the article and the /‑ɛ/ attributive adjectival suffix. In judgment tasks 5 and 6, speakers behaved largely uniformly, accepting a much wider variety of forms than would be expected in pre-War or Standard varieties and, in the case of the homogeneous group of speakers, a wider variety than their production would suggest.

While most speakers were consistent in their mixed or homogeneous use of morphology, other speakers’ behavior varied across tasks. MN5, MN6, and MI8 were consistently the most mixed in their behavior, with MI6, MM1, MN4, FN6, and MN8 all using mixed forms in more than half of the tasks. The remaining speakers (32, or 80%) were mostly or entirely homogeneous in their behavior.

The factor that most strongly predicted this behavior was not the speaker’s age, gender, or location, but rather the speaker’s active engagement with and interest in the Yiddish language. Some of the mixed speakers were teachers of Yiddish (either in secular or Haredi contexts), while others enjoyed studying the grammar and etymology of the language for its own sake or had an interest in Yiddish-language media (again, either secular or Haredi). However, even the most consistently mixed speakers do not appear to have a productive system of morphological case and gender in Yiddish, as demonstrated by their inconsistent use of morphology across the tasks and their high rate of acceptance of a wide variety of forms in tasks 5 and 6. We therefore argue that Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish lacks morphological case and gender on full nominals, and that its speakers do not have such concepts in their mental grammars of the language.

Task 6, in particular, revealed a preference (specifically among men) for דער der forms in the subject position over accusative or dative forms, regardless of noun gender; it also revealed a related preference for דעם dem forms in the object or prepositional object position over nominative forms, again, regardless of noun gender. However, this tendency does not seem to indicate that the participants have a productive case and gender system. Rather, it seems akin to the tendency among native speakers of contemporary English to distinguish between who and whom or I and me in sentences such as It is I or He visited John and me. The use of the different forms in this case is not indicative of a systematic grammatical distinction; instead, it appears to reflect the speakers’ vestigial awareness of an older stage of the language. This is true both of English and of Yiddish.

Our findings are supported by metalinguistic discussion with partici-pants. Very few participants thought that determiner and attributive adjective forms might be associated with grammatical gender, and none associated them with case. Often, participants thought of the different determiner forms as spelling variants rather than distinct grammatical forms.

One somewhat surprising finding concerns differences between the older (aged 50 and up) speakers of the vus and vos dialects. In particular, older vus speakers were significantly less likely to use variable case and gender morphology than older vos speakers (including Litvish, Chabad, and Jerusalem Yiddish speakers). For example, the oldest participant in our study, MI10, was an 87-year-old vus speaker. In tasks 1 and 2, he used a single spoken definite determiner form, /dɛ/, and the invariant attributive adjective form /-ɛ/. His partial results from the other tasks suggest a similarly non-standard-like use of morphology. Similarly, FI3, a vus speaker in her late 50s, consistently used an invariant form, although she did accept a wide variety of forms in tasks 5 and 6. During the metalinguistic discussion she expressed surprise that different forms could be associated with morphological gender or case. Both MI10 and FI3 are fluent speakers of Modern Hebrew and are thus familiar with the idea of morphological gender.

In contrast, the speakers who most consistently used a variety of forms—MN5, MN6, and MI8—were all vos speakers between the ages of 50 and 75. All three grew up in consistently vos-speaking environments in Litvish, Chabad, or Jerusalem Yiddish communities. Given that these communities trace their roots back to Northeastern Yiddish, which had only two genders and thus a simpler morphological paradigm, they could perhaps be expected to have maintained morpho-logical case and gender distinctions longer than the descendants of speakers with a three-way gender distinction.

However, even these older vos speakers do not appear to have a productive morphological case and gender system; they seem to be making use of forms that they know exist in some other system (or use them in free variation). Furthermore, all three speakers used and accepted morphological forms associated with neuter gender, underlining the distinction between morphology in their variety and one in Northeastern Yiddish. Note, however, that MI7, a speaker of vos in his 50s, who grew up in a mixed vos- and vus-speaking environment, consistently used invariant case and gender morphology while accepting other forms in tasks 5 and 6.

These results suggest that the loss of morphological case and gender might have happened a generation later in vos-speaking Chabad, Litvish, and Jerusalem Yiddish communities. This would explain why older vos speakers appear more aware of and more likely to use variant morpho-logical forms than either younger vos speakers or both younger and older vus speakers. We believe there are two main factors contributing to this: Speakers in these communities traditionally tended to be more isolated from other Yiddish-speaking groups, and the morpho-phonological inventtory of the vos dialect made survival of a variety of forms more likely.

As far as the first factor is concerned, in Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a we argue that the loss of morphological case and gender in Stamford Hill Hasidic Yiddish was, in part, due to a greater dialect and speaker diversity: In the years after the Holocaust, Hasidic Yiddish-speaking communities, including the ones in Israel, the USA, and the UK, spoke a much wider range of geographical dialects and possibly had a larger number of L2 speakers than pre-War communities in Eastern Europe. Different geographical dialects might assign different morphological gender to particular nouns or have varying patterns of syncretism. These mixed communities, therefore, provided less consistent input on the use of case and gender morphology to children acquiring the language.Footnote 24

In contrast, Jerusalem, Chabad, and Litvish Yiddish-speaking communities were not subject to the same linguistic pressures at the time, although for different reasons. The Jerusalem Yiddish-speaking commu-nity has traditionally been insular and mixed very little with outsiders. Many contemporary Chabad Yiddish speakers are children of so-called shluchim (Jewish outreach workers as part of the Chabad mission), who used Yiddish as a lingua franca to communicate with family members but used other languages in other contexts. Litvish Yiddish speakers did not traditionally have much contact with Hasidic Yiddish speakers, as there is very little intermarriage between Hasidic and non-Hasidic Haredi communities, compared to intermarriage between (non-Chabad) Hasidic sects. Furthermore, use of Yiddish is much less widespread amongst Litvish communities than it is among Hasidic communities. Thus, for the older generation of speakers, their linguistic input was a relatively homogeneous Northeastern-derived dialect.

However, the older generation of Litvish, Chabad, and Jerusalem Yiddish speakers represented in this study now speak Yiddish with members of other (usually vus-speaking) communities regularly. The younger generation of speakers have similar levels of contact with vus speakers and are often educated in mixed or vus-speaking institutions. Younger vos speakers from the same communities behave no differently than their vus-speaking counterparts. We believe that this mixing of traditional dialects is thus a major factor in driving the loss of morphological gender and case in the Yiddish of contemporary Haredi speakers. Furthermore, we argue that the process of change that has taken place in both vos- and vus-speaking communities has reached the same point, namely, a complete lack of productive morphological case and gender system in speakers’ mental grammars. For this reason, and because the change seems driven by contact with Hasidic speakers, we feel justified in using the term Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish for the language of both vos and vus speakers of any Haredi affiliation.

The second factor is the distinct morphophonological profile of Northeastern Yiddish. Speakers of vus pronounce די di with a vowel ranging between [ɛ] and [ǝ], whereas speakers of vos use /i/. Both groups of speakers pronounce דער der with [ɛ], meaning that the vowels in the two forms of the determiner are further away in the vowel space of vos speakers than they are for vus speakers. Additionally, many historical Mid- and Southeastern varieties had processes of /r/ vocalization or elision, rendering the distinction between these two forms of the definite determiner even less conspicuous. Several historical dialects already had some case and gender syncretisms along these lines. Taken together, these phonological developments made the distinction between the דער der and די di forms of the determiner more perceptually salient in varieties of the language related to Northeastern Yiddish than in other varieties.

In addition to the generational and dialectal issues, other sociolinguistic factors also seem to play a role. Specifically, speaker gender appears to affect choice of written definite determiner and attributive adjective morphology. Women appear to be more innovative, making greater use of novel written forms, such as דע de, ד׳ d’, and ד d. They appear to prefer forms that more closely match their pronunciation, whereas men are more likely than women to use and to accept a variety of existing forms. These trends are somewhat clearer in the written language, as very few speakers make consistent use of a variety of definite determiner and attributive adjective forms in spoken Yiddish.

Perhaps unexpectedly, the country in which the participants grew up did not appear to affect their use of definite determiner and attributive adjective forms. This is important because some of the coterritorial languages, such as Modern Hebrew and French, have morphological gender marking. Nevertheless, Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish speakers uniformly lack such distinctions in their Yiddish. These observations suggest that gender (and case) morphology is not subject to external influence from the coterritorial languages—otherwise one would expect gender morphology in Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish from Israel and French-speaking countries. The loss of case and gender morphology must be an internal change, the conclusion also reached by Krogh (Reference Krogh, Aptroot, Gal-Ed, Gruschka and Neuberg2012, Reference Krogh, Elmentaler and Hundt2015).

Note that this rapid development is also not an inevitable result of a minority language situation: As discussed in Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a, Pennsylvania German and Volga German as spoken in Kansas have retained morphological case and gender in spoken and (for Pennsylvania German) written forms over a much longer period than Hasidic Yiddish (see Huffines Reference Huffines and Dorian1989, Ferré Reference Ferré1991, and Stolberg Reference Stolberg2015 for discussion of Pennsylvania German, and Khramova Reference Khramova2011 for discussion of Volga German in Kansas).

6. Conclusion

This paper has shown that there is a complete absence of morphological case and gender in the spoken and written Yiddish of several generations of Haredi speakers in four main Hasidic centers worldwide (Israel, the New York area, and to a lesser extent, Antwerp, and Montreal). One of the reasons that we wanted to compare speakers from the different communities was to ascertain whether or not there was an effect of the coterritorial languages (chiefly English, Modern Hebrew, and French) on participants’ Yiddish case and gender. This is important because some of these coterritorial languages, for example, Modern Hebrew and French, have morphological gender marking. Crucially, our findings show that Hasidic Yiddish speakers in all geographic locations uniformly lack such distinctions in their Yiddish.

In speech, our participants from all communities uniformly employed an invariable form of the determiner, /dɛ/ or /di/, for all nouns, regardless of the gender and case of these nouns in the pre-War and Standard varieties of Yiddish. They almost always employed an invariable form of adjectives, with the pre-War and Standard Yiddish feminine nominative and accusative suffix ‑ע ‑e having been reanalyzed as an attributive marker. When asked to produce the written form of the determiner along with a noun in the dictionary (nominative) form, speakers employed a variety of strategies, one of the most common being to select the variant די di—traditionally the feminine singular nominative and accusative determiner, as well as the plural determiner—across the board. This is likely due to the fact that in the communities in question this is the traditional determiner whose sound most closely resembles the spoken variant /dɛ/ or /di/. This strategy can be contrasted with that found in London’s Stamford Hill community, where participants commonly selected the variant דער der—traditionally the masculine nominative—as it corresponds more closely with their pronunciation of the oral variant /dɛ/ (see Belk et al. Reference Belk, Kahn and Eszter Szendrői2020a for discussion of this point). A smaller group of speakers employed a mixed pattern in their written data, which nevertheless revealed a highly inconsistent use of the different forms of the determiner and attributive adjectives. This inconsistent use of variable forms in writing corresponds to the lack of distinction between these forms in spoken language. Metalinguistic discussion confirmed that the speakers were unfamiliar with the rules governing the selection of one determiner as opposed to another in any given instance, which points to the absence of such forms in the speakers’ mental grammar and the lack of systematic instruction in their use in written language in school.

A prominent reason for this rapid change in the grammar of Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish may be the large-scale destruction of the traditional Eastern European Hasidic Yiddish speaker base and the subsequent geographic dispersal of most of the surviving speakers. This development, in turn, led to a major change in the demographics of Hasidic Yiddish-speaking communities, increased dialect mixing, greater contact between Hasidic and non-Hasidic Haredi speakers, a large influx of L2 speakers, and the emergence of a koiné variety of the language that became prevalent in all post-War Hasidic centers worldwide. This koiné variety has a new nominal system that does not exhibit morphological case and gender. Our findings, based on our analysis of data from native Yiddish speakers from the main Haredi (primarily Hasidic) centers on three different continents, reveal this caseless and genderless system to be a firmly entrenched characteristic of their language. The loss of morphological case and gender appears to have been driven by developments among Hasidic speakers, leading to a new variety of the language, Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish. This variety is not only shared by all Hasidic communities globally, but it has also led to significant change in the way Yiddish is spoken throughout the entire Haredi world.

APPENDIX

Participants’ codes follow the following convention. The first letter refers to the speaker’s gender: F=female, M=male; the second letter refers to the speaker’s location: I=Israel, N=New York area, M=Montreal area, A=Antwerp; the following number identifies the speaker uniquely in their gender-location group. So, for instance, MI6 refers to Israeli Male Speaker, number 6. The subscripts indicate whether or not the speaker speaks a vos pronunciation, which is indicated by the subscript o; a vus pronunciation, indicated by u; or a mixed pronunciation, indicated by m.

Table A1 shows the breakdown of forms used with the different feminine, masculine, and neuter nouns in the singular in Standard Yiddish in task 3, by speaker location (Montreal and Antwerp speakers are omitted).

Figure A1. Distribution of participants by age.

Table A1. Distribution of forms used with singular feminine, masculine, and neuter nouns in Standard Yiddish by speaker location, task 3.