1. Introduction

This article presents an experimental study investigating the relationship between the perception and production of a specific socially meaningful variable phenomenon: variable liaison in spoken French. The expression social meaning can refer to a number of different things, given its use in fields as varied as sociolinguistics, philosophy, formal semantics and linguistic anthropology; however, in this article we follow Podesva (Reference Podesva2011) who comes from a sociolinguistics perspective and defines it as referring “to the stances, personal characteristics, and personas indexed through the deployment of linguistic forms in interaction” (Podesva, Reference Podesva2011: 234; see also Beltrama, Reference Beltrama2020; Burnett, Reference Burnett2023). In sociolinguistics, whether a linguistic unit has social meaning, and what the nature of that meaning is, are usually taken to be diagnosable in both perception and production.

From the perception side, sociolinguists often employ experimental paradigms such as the Matched Guise Technique (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Hodgson, Gardner and Fillenbaum1960). In a matched guise experiment, participants listen to samples of recorded speech (called guises) that are designed to match as much as possible, differing only in the linguistic phenomenon studied. Each participant is exposed to only one of the guises, and after hearing it, their beliefs and attitudes towards the speaker are assessed, usually via questionnaire. Following up on early studies by Labov (Reference Labov2006 [1966]), Campbell-Kibler (Reference Campbell-Kibler2006; Reference Campbell-Kibler2007) showed how such methods, imported from social psychology, could be relevant for variationist sociolinguistics, which studies what social, grammatical and cognitive factors condition the use of sociolinguistic variants, e.g. grammatical alternatives like –ing and –in’ (as in working vs workin’, see Labov, Reference Labov1972; Tagliamonte, Reference Tagliamonte2012). Using the matched guise technique, Campbell-Kibler demonstrated that there exist consistent associations between the sociolinguistic variants –ing and –in’ and the properties that US English listeners attribute to speakers who use these variants. For example, participants in Campbell-Kibler (Reference Campbell-Kibler2009)’s matched guise study rated speakers as significantly more educated and more articulate in their -ing guises than in their –in’ guises. The use of the matched guise technique and related experimental paradigms has now become a standard way to study the perception of sociolinguistic variables (e.g., Levon, Reference Levon2007; Podesva et al., Reference Podesva, Reynolds, Callier and Baptiste2015; D’Onofrio, Reference D’Onofrio2018; Villareal, Reference Villarreal2018; among many others).

The discovery that differences between sociolinguistic variants could be diagnosed through sociolinguistic perception experiments has contributed to making social meaning a central object of study in variationist sociolinguistics. In particular, the development of the concept of indexical fields (Eckert, Reference Eckert2008) has helped analysts capture the complex meanings variants may have, including properties like educated or articulate, which can be tested in perception experiments. Indeed, the Third Wave framework (Eckert, Reference Eckert2012; Reference Eckert2018), which grew out of ideas from linguistic anthropology and ethnographic approaches (see Silverstein, Reference Silverstein1979; Ochs, Reference Ochs, Duranti and Goodwin1992; Eckert, Reference Eckert2000; among others), has been heavily influential in the development of our understanding of social meaning and its articulation with perception.

The idea that social meaning may be a driving force in both perception and production raises the question of how closely the two actually line up. Indeed, recent studies formally modelling sociolinguistic perception and/or production (such as Burnett, Reference Burnett2019; Reference Burnett2023; Beltrama, Reference Beltrama2020; Kleinschmidt et al., Reference Kleinschmidt, Weatherholtz and Jaeger2018) take for granted that there is a (more or less) transparent relationship between perception and production, where the former is, in some way, learned from the observations about the latter. As discussed by Squires (Reference Squires2013), this is also an assumption underlying much research in the exemplar theoretic framework (Bybee, Reference Bybee2001; Pierrehumbert, Reference Pierrehumbert, Bybee and Hopper2001).

In the past decade, there has been some interest in investigating whether speakers and listeners are sensitive to the same kinds of properties or categories. For instance, Eddington and Brown (Reference Eddington and Brown2020) found that in production, the realization of prevocalic, word-final /t/ in US English (e.g., not ever), produced with a glottal stop (i.e., [nɑʔɛvɚ]), was negatively correlated with speaker age (i.e., more glottal realizations by younger speakers). Using a matched guise task, they similarly found that listeners from five different US states rated speakers producing glottal stops in this phonological context as slightly younger than speakers producing other variants. Although this expected transparent relationship between production and perception is sometimes observed (i.e., I more often hear younger speakers producing a glottal stop, so when I hear someone produce a glottal stop, I infer that they are younger), it is often the case that there are some differences. In that same study, the authors found age-stratified variation in production for the same variable in a different phonological context; yet, listeners in their perception study did not show associations between specific realizations and the speaker’s age. Similarly, Squires (Reference Squires2013) showed that while participants in her study showed knowledge about the social patterning of certain syntactic constructions (e.g., non-standard there’s+NPPL which is associated with working class speakers) they did not necessarily rely on this (macro-level) knowledge when perceiving utterances in context. Specifically, they did not assume that an utterance of there’s+NPPL was more likely to be produced by a working class speaker than by a middle class speaker, despite knowledge that this trend exists at the level of the population. In fact, this follows the overall trend in the literature showing that social conditioning patterns that are found in production (i.e., corpus) studies are not always reflected in perception studies (e.g., Squires, Reference Squires2013; Alderton, Reference Alderton2019; Hilton and Jeong, Reference Hilton and Jeong2019; Eddington and Brown, Reference Eddington and Brown2020).

In this research note, we present the first data considering the social meaning of variable liaison in spoken French that allows a reliable comparison between perception and production. The social meaning of realized variable liaison is still debated, but recent work has drawn a clear link between liaison and the written form, in particular tying the realization of variable liaison to meanings like professional. Below, we detail an experimental investigation of variable liaison’s social meaning potential, comparing previous perception results with results from a new production experiment. We observe the opposite pattern from what is described above: listeners interpret social meaning for realized variable liaison that speakers do not appear to exploit in their productions in our task.

1.1 Variable liaison in spoken French

Liaison is a phenomenon in spoken French where a word-final consonant is realized if the following word begins with a vowel but is not pronounced in other phonological contexts. For example, the plural definite article les is pronounced as [le] in the phrase les copines ‘the girlfriends’, but as [lez] in the phrase les amies ‘the girlfriends’. Many words in French end in a liaison consonant, but their realization is not uniform. While some liaison consonants are always produced when the following word begins with a vowel, in other cases realizations are variable. For example, the adverb trop ‘too much’ ends in an optional liaison consonant /p/. In a phrase like il est trop abîmé ‘it is too damaged’, the sequence trop abîmé may be realized with liaison as [tʁopabime] or without liaison as [tʁoabime]. Such cases will be the focus of our study: variable liaison. Different linguistic accounts of variation in the realization of variable liaison have been provided in the literature, relying on notions like syntactic cohesion or frequency and transition probabilities (see Côté, Reference Côté, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011, for a thorough review). However, so-called extra-linguistic factors have long been of central concern to the analysis of variable liaison (for an excellent review of historical and contemporary sociolinguistic treatments of liaison, see Hornsby, Reference Hornsby2020).

Style, particularly entangled with conceptions of social class, was quickly proposed as the most important factor conditioning variation in liaison (Delattre, Reference Delattre1955). Specifically, Delattre proposed that more liaisons are realized in more elevated registers, but only in the “language of the most cultivated class” (Delattre, Reference Delattre1955: 45, our translation). Indeed, as summarized by Hornsby (Reference Hornsby2020: 131–135), realization of variable liaison has long been proposed to reflect social stratification by socioeconomic class (with elite speakers hypothesized to produce more variable liaisons on average than working class speakers). However, clear empirical support for this hypothesis has remained elusive: “le marquage social positif opéré par la liaison reste ainsi à démontrer très précisement” (Durand et al., Reference Durand, Laks, Calderone and Tchobanov2011: 111). That an analysis in terms of social class is insufficient can be seen by comparing the corpus studies of Malécot (Reference Malécot1975) and Laks (Reference Laks1983). The corpora used for both studies were collected in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with Malécot’s interviews being conducted with “members of the educated middle-class of Paris” and Laks’ corpus being collected in Villejuif, a traditionally working-class suburb of Paris. Both studies relied on spontaneous speech, and both reported very low overall rates of variable liaison; that is, both speakers taken as the Paris “elite” and speakers taken as the Paris “working class” used similar low rates of variable liaison in spontaneous conversational speech. Later work looking at a corpus of political speech similarly found no clear evidence of a link between a speaker’s socioeconomic background and their rate of realized variable liaison (Encrevé, Reference Encrevé1988). Encrevé proposed that politicians could in fact use (non-)realization of variable liaison to “jouer alternativement (et parfois simultanément) la stratégie d’identification et la stratégie de l’imposition de légitimité” (1988: 267), depending on where they are situated in the political field and what section of the electorate they are targeting. These are probably the clearest early proposals of the social meanings that might be associated with variable liaison. In line with “la stratégie d’imposition de légitimité”, Hornsby (Reference Hornsby2020: 196, emphasis our own) proposes that speakers could “signal written or prepared discourse through realisation of orthographic consonants.” Thus, realized variable liaison, insofar as it involves the production of a consonant that is always present orthographically, is somehow linked to the written form, a proposal that has garnered significant attention in the literature on liaison (see in particular the recent special issue of Langue Française entitled, “Liaison between orality and scripturality” Hornsby et al., Reference Hornsby, Laks and Pustka2023). Hornsby continues:

…discourse which is neither prepared nor scripted would show lowest incidence of variable liaison and befit speech events in which neither the speaker’s authority nor his or her professional expertise are at issue. (Hornsby, Reference Hornsby2020: 200, emphasis our own)

This analysis accounts neatly for the relatively high rates of liaison observed in (semi-)prepared speech (Ågren, Reference Ågren1973; Encrevé, Reference Encrevé1988; Pustka, Reference Pustka2017) compared to spontaneous speech (Durand et al., Reference Durand, Laks, Calderone and Tchobanov2011; Coquillon and Turcsan, Reference Coquillon, Turcsan and Gess2012; Hornsby, Reference Hornsby2019; Reference Hornsby2020). Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Abbou and Burnett2023) recently developed this idea further in a study that focused on how social representations of the written form (writing as a technology allowing for the codification of rules and laws, but also as a tool allowing for thoughtful [linguistic] preparation; orthography as a shared norm; deviation from the norm as creativity) were themselves related to structured value systems that are relevant for contemporary France. Their proposal was couched within a social theoretical framework called the pragmatic sociology of critique (Boltanski and Thévenot, Reference Boltanski, Thévenot and Porter2006, et seq.) and forms the basis of the present study. Below we summarize the key points of the proposal and recall their principal finding before detailing our own experimental study of the social meanings of variable liaison in spoken French.

1.2 The multiple worlds of meaning making

Much of the previous sociolinguistic work on variable liaison has operated within an understanding of the social world in which social structures determine individuals’ behaviour. In this view, individuals are seen as passive “agents” whose linguistic behaviours are shaped by (and thus reproduce) their social environment (à la Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1979).Footnote 1 The expectation that elite or working class speakers would show a specific rate of realized liaison is in line with such an understanding. However, such an approach has so far not yielded a solid understanding of the social meaning(s) of variable liaison, and does not offer us a clear path to the understanding of the link between the written form and realized variable liaison.Footnote 2 Therefore, in the present work, we follow Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Abbou and Burnett2023) and shift the focus of our attention from exclusively structural elements of society to the interplay between higher-level social objects (e.g., shared norms and values) and individual agency.Footnote 3 We will specifically focus on the ideological dimension of social action, which can be captured with axiologies. Axiologies refer to a specific value system that is structured around an agreed upon form of the “common good” (thus shared amongst members of a given society), and more specifically, here, we follow recent work by focusing on the value systems (axiologies) referred to as “economies of worth”, described by Boltanski and Thévenot (Reference Boltanski, Thévenot and Porter2006) in their pragmatic sociology (a current of sociology developed as a response to Bourdieu’s school of critical sociology; see Boltanski, Reference Boltanski and Elliott2011).

Pragmatic sociology considers individual (linguistic) action to be caught up in moral agency (the capacity of social actors to critically reflect on their own behaviours as well as those of others), as well as ideological choices and structural assignments, and while the study of axiologies is not by itself able to capture or explain all social phenomena – it must of course be situated as an approach amongst others, aiming to shed light on certain aspects of the social world – a focus on axiologies may prove to be a fruitful avenue for the study of liaison (and potentially of a certain number of other sociolinguistic phenomena). The study of axiologies (and pragmatic sociology in particular), as sets of shared values within a society, aims to account for language users’ agency as it plays out within specific socio-historical dynamics of norms and values, considering both how social actors critique others’ behaviours, as well as how they justify their own, yielding an ideal arena for comparative study of perception and production. If we want to consider how individuals make (linguistic) choices and act in the name of certain sets of beliefs, we must draw on a framework which takes axiologies as its starting point, and the pragmatic sociology of critique thus seems to be a suitable candidate.

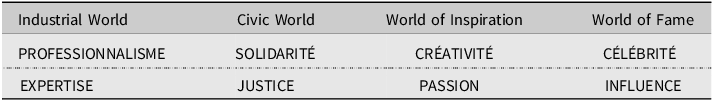

For an accessible synthesis of pragmatic sociology, we refer readers to Jacquemain (Reference Jacquemain2008), while Boltanski and Thévenot (Reference Boltanski, Thévenot and Porter2006) and Boltanski (Reference Boltanski and Elliott2011) provide a more in-depth presentation of the framework and its context. The baseline is that “there are different kinds of ‘principles’Footnote 4 that people can invoke” (Jacquemain Reference Jacquemain2008: 5) to justify their (linguistic) actions (which we as sociolinguists can in turn analyse as social meaning). In their book On Justification, Boltanski and Thévenot (Reference Boltanski, Thévenot and Porter2006) propose an architecture of principles organized in terms of polities and worlds, which Jacquemain (Reference Jacquemain2008: 2) refers to as a kind of “grammar” for multiple regimes of action. Here, we focus on four reference worlds from pragmatic sociology:

-

• The Civic World is articulated around the idea that the collective prevails. It mobilises the registers of representativeness, legality, officialdom.

-

• The World of Fame rests on the central principle that “reality is what people think it is,” and capitalizes on core ideas such as opinion, glory, and social recognition.

-

• The Industrial World is articulated around the principles of efficacy and performance, yielding a merit-based hierarchy.

-

• The World of Inspiration values breaking away from pre-determined customs and behaviours, focusing on the principle of creativity.

Crucially, worlds are populated by typical objects and beings (which reflect the corresponding core principles), and while any object or being can move between worlds (movement between worlds thus contributing to situational meaning making), their typicality of a given world can also be used by actors as a concrete manifestation of that world (i.e., a way of recognizing a world, a reinforcement of already present meaning). A stopwatch, which allows the precise measurement of the passing of time, might be an object typical of the Industrial World (e.g., in that it reflects the relevant core principles, allowing an objective measurement of efficacy), but if this stopwatch is safeguarded as a cherished family heirloom passed down through the generations, it may be, in a certain situation, an object of the Domestic World (an additional world which values tradition and ritualization).

Returning to (linguistic) social meaning, within this framework, certain kinds of linguistic variables can be considered as objects, which, like the stopwatch, have a complex indexical structure. Objects then have many various meanings potentially linked to them, a “constellation of meanings” that form an indexical field (Eckert, Reference Eckert2008). The situationally relevant meaning(s) are picked out as a function of the world a given situation is governed by. In the present case, realized variable liaison can be viewed as an object with a complex indexical relation to the written form. Social actors can utilize this indexical relation to position themselves and others in a social situation, giving meaning to the realization of variable liaison as a function of the world at play.

2. Perception

Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Abbou and Burnett2023) tested the potential social meaning associations that listeners attributed to (non-)realization of variable liaison in perception within the framework sketched above. Here, we briefly recall the principal result of that study, though we refer readers to the full article for more detail on the methodology.

The study was a task inspired by the Matched Guise Technique (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Hodgson, Gardner and Fillenbaum1960) and was framed as an evaluation of a casting call for voice actors. On each of 32 trials, participants (N = 60) were shown a small contextualization text depicting a social interaction that was meant to strongly evoke one of the targeted worlds, along with an instruction from the casting director indicating a target value (e.g., “The actors were asked to embody passion.”). These target values (two per world) were selected during two norming studies and are reproduced in Table 1. Following the contextualization text, participants heard two recordings of the same quotation, produced by two different voice actors (guises). Their task was to select the voice that they thought best portrayed the character in the social interaction while following the instruction of the casting director.Footnote 5 Crucially, the quotation always included exactly two variable liaison sites. One of the liaison sites involved a form of the verb être (e.g., c’était incroyable ‘it was incredible’), while the other varied and could be an adverb (e.g., trop abîmé ‘too damaged’), a plural noun (e.g., difficultés exceptionnelles ‘exceptional difficulties’), etc. One of the guises presented to participants included realized liaisons while the other did not. The authors then measured how often participants selected the realized guise or the non-realized guise in the different worlds.

Table 1. Target values (in the original French) for each world

Overall, participants selected the guise with realized variable liaison only slightly more than half the time (i.e., near the 50% chance level). Participants had a significantly higher preference for the realized guise only on trials that depicted a scene in the Industrial World, and specifically on trials where the voice actors were supposedly told to embody professionnalisme. The authors attributed this to the social representations of writing which align strongly with the values of the Industrial World, and concluded that listeners can attribute social meaning to the realization of variable liaison during interactions in the Industrial World, but not necessarily in other social situations. Thus, listeners associate the realization of liaison with a speaker aiming to portray professionalism, specifically in a social interaction where professionalism is at issue (i.e., an interaction in the Industrial World).

Having established the social meaning potential of realized variable liaison in perception, we can now examine if speakers are in turn likely to use the realization of liaison to position themselves. Below, we provide a test of the flip side of the coin of social meaning: production.

3. Production

Our production study was based on the perception study described above, but was framed as a voice acting exercise, rather than the evaluation of already recorded actors. Here, amateur and professional actors were asked to play the characters described in the stimulus texts to see if those interactions with characters clearly positioning themselves in the Industrial World would yield higher rates of variable liaison than interactions taking place in other worlds, as suggested by Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Abbou and Burnett2023).

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

We sought to recruit both amateur actors (i.e., individuals actively participating in either an acting class or a non-professional theatre group) and professional actors whose life was more anchored in the acting world. Participants were thus recruited through two principal sources: firstly by contacting active theatre groups in the Paris area, and secondly by posting an ad to an actor recruitment website.

We recruited 17 amateur actors and 10 professional actors to take part in our experiment. The experiment lasted between 10 and 15 minutes, and participants received a 10 EUR gift card as compensation.

3.1.2 Stimuli

The stimuli were a subset of the experimental items from Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Abbou and Burnett2023). Each item included a contextualization text describing a character, including their name and main activity (e.g., studies or profession) and a quotation from the character. Each text presented the character involved in a social interaction typical of the relevant world (e.g., an accountant giving financial advice to a client [Industrial World]) and ended with a statement indicating that the character was about to speak, followed by the quotation. Again, the quotation contained exactly two possible liaison sites, one involving the verb être (e.g., c’est impossible ‘it’s impossible’) and one involving another type of site (e.g., trop important ‘too important’).

Each item was designed to strongly evoke one of the targeted worlds, which was verified in two norming studies (for details, see Martin et al., Reference Martin, Abbou and Burnett2023). We selected the four items in each world (Industrial, Civic, Inspiration, Fame) for which participants showed the most consistent preferences in the norming studies, yielding a total of 16 final experimental items.Footnote 6

3.1.3 Procedure

Participants were usually recruited in groups, but were tested one-by-one by a research assistant. They were told that they would have to play a series of characters engaged in a social interaction. They were told that for each character, they would have to embody a specific value that would be shown to them before reading the contextualization text. The stimuli were presented in a pseudo-randomized PowerPoint presentation (such that no two trials in a row were presented with the same target value).

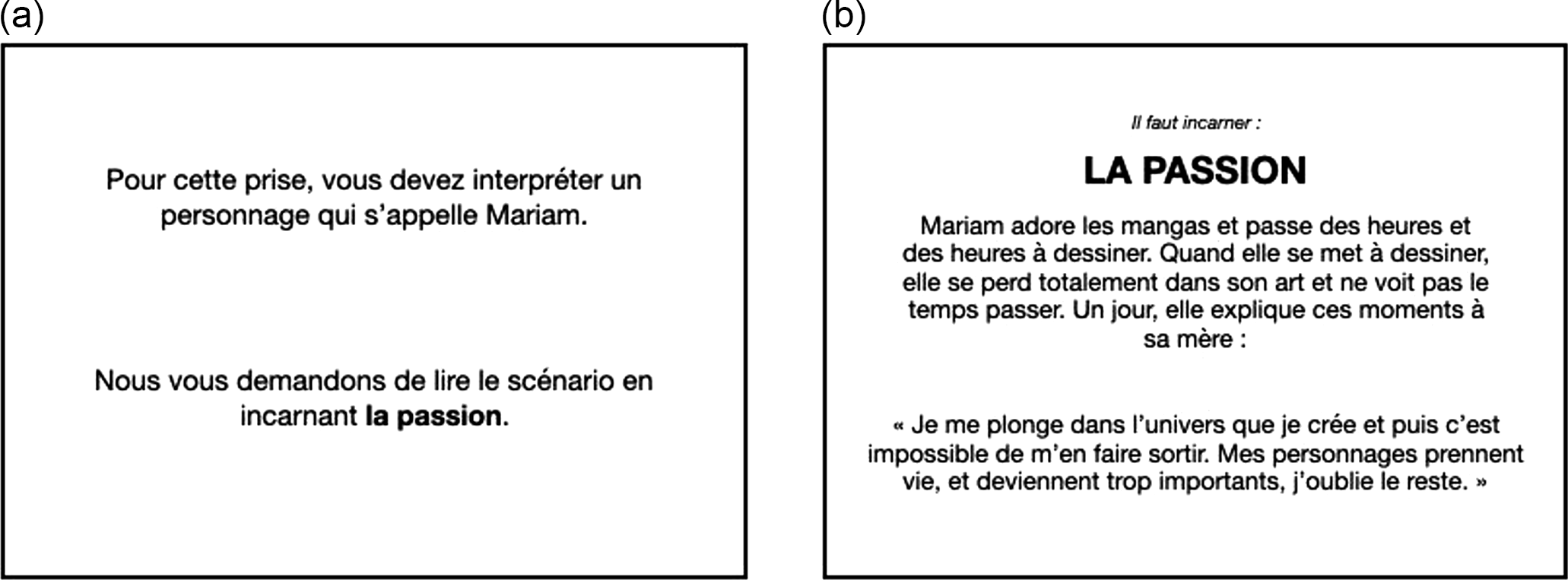

Each trial began with the presentation of the name of the character that the actors would portray and the specific instruction related to the target value (see Figure 1a). This instruction presented one of the two values, randomly selected, associated with the world of the item. For example, if the trial was in the World of Inspiration, participants were told either to embody creativity or passion. Participants were never told about the world manipulation, or that any of the values related to one another; they encountered each item only once.

Figure 1. Example trial from the World of Inspiration in the original French.

After the presentation of the character name and instruction, the instruction was moved to the top of the screen with the target value shown in a large font in bold. Underneath this instruction, the item text appeared, describing the character and the social interaction. Immediately underneath the contextualization text was the quotation from the character that the participants were asked to read (see Figure 1b). For each of the two liaison sites, we recorded whether the participant realized the liaison (1) or did not (0). Note that in contrast to the perception task presented in Section 2 (see fn. 5), participants in our production task were not given any explicit mention of the liaison sites. If a participant stumbled while reading or re-read the quote for any reason, only their final production was analysed. Participants thus each provided 16 final takes containing two liaison sites each. Participants were recorded using a mobile phone and recordings were manually coded offline.

3.2 Results

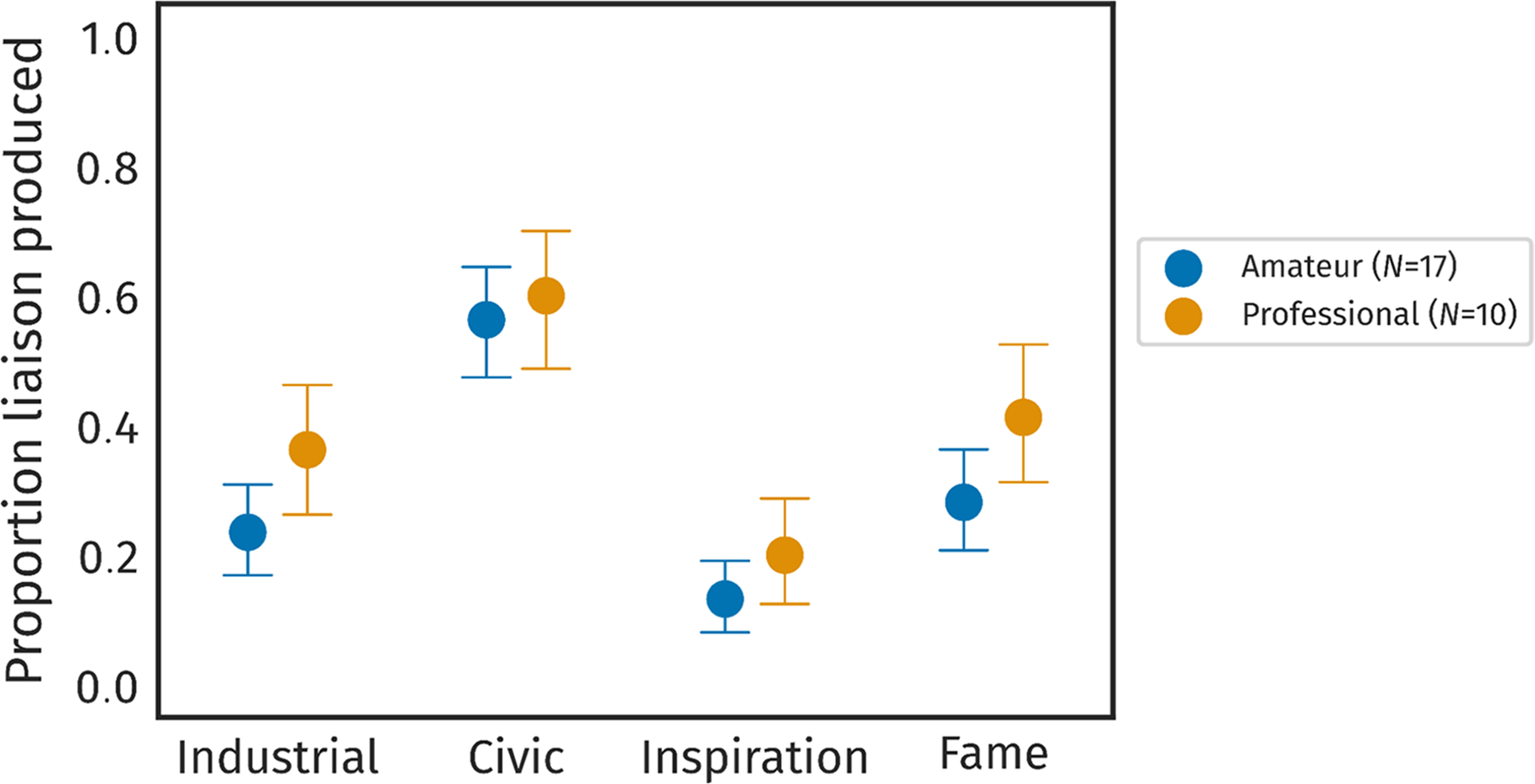

Rates of realized variable liaison per world are visualized in Figure 2. We analysed the data using logistic mixed-effects models implemented in R with the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). Following Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Abbou and Burnett2023), we examined whether our participants produced higher rates of variable liaison in the Industrial World trials than they did on average across the experiment. For this, we created three deviation coded factors to express the comparisons of the four worlds to the grand mean (mean liaison production = 33.6%),Footnote 7 along with a contrast coded factor to compare preferences of the amateur and professional actors, and the interactions between these factors. Alongside these factors, we included by-participant and by-item random intercepts. This full model was compared to simpler models that excluded one of the fixed effects or interactions, using a likelihood ratio test. The model excluding the factor distinguishing professional and amateur actors was not found to significantly differ from the full model (β = 0.63, SE = 0.43, χ 2(1) = 2.1, p > 0.05), indicating no reliable evidence for a difference between the performance of the two groups. The model excluding the factor comparing the Industrial World to the grand mean was similarly not found to significantly differ from the full model (χ 2(1) < 1). However, the models excluding the factors comparing the Civic World and the World of Inspiration to the grand mean were both found to significantly differ from the full model (Civic: β = 1.96, SE = 0.87, χ 2(1) = 4.5, p < 0.05; Inspiration: β = −1.88, SE = 0.90, χ 2(1) = 4.0, p < 0.05). None of the models excluding the interactions between these three factors and the factor distinguishing professional and amateur actors were found to differ significantly from the full model (all χ 2(1) < 1).

Figure 2. Proportion realised liaison by world for both amateur and professional actors. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals calculated on participant means.

We thus did not find the same pattern of preferences in production as was previously observed in perception. Instead, we saw above-average realization of variable liaison in the Civic World, and below-average realization of variable liaison in the World of Inspiration. Before interpreting this as a result of our experimental manipulation (i.e., analysing these productions as driven by social meaning), we should consider that this experiment used only a subset of the full experimental materials from the original perception experiment. We should thus verify that the patterns observed in production cannot be explained by specific features of this subset of stimuli. In the perception experiment discussed in Section 3, each participant saw 16 liaison sites per world. In the production experiment, this was reduced to eight, meaning each data point carried more statistical weight. If there are specific linguistic contexts that are more (or less) likely to be produced with liaison (all else being equal), these contexts could weigh more heavily in our production experiment than they did in the perception experiment and cause certain worlds to show higher (or lower) rates of liaison.

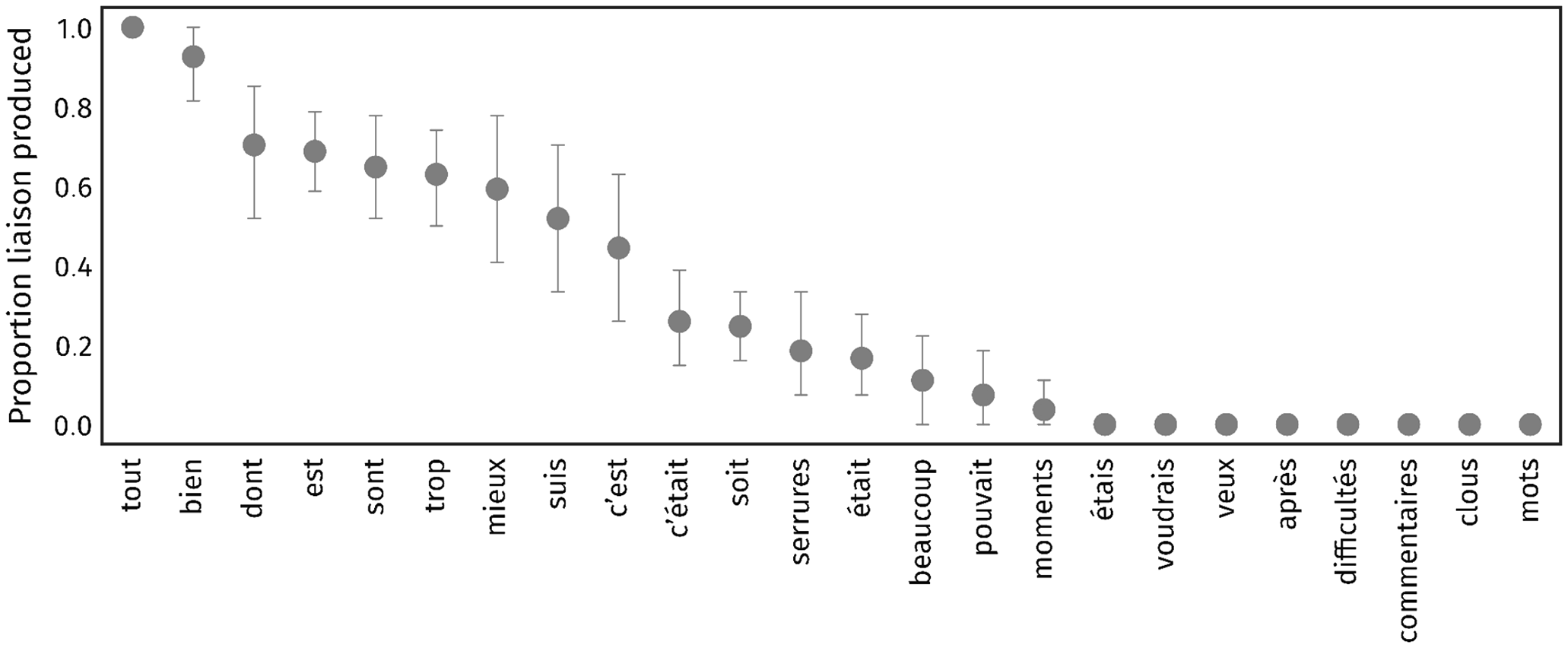

We therefore looked at the various linguistic contexts that remained in the stimuli used in this experiment. Figure 3 shows the rates of realized liaison in the 24 unique “word 1” contexts, combining the data from the different worlds and from professional and amateur actors.Footnote 8 “Word 1” corresponds to the word with the potential liaison consonant (e.g., “trop” in trop abîmé). Figure 3 shows a great range of word-based variability, with some words being produced with liaison (almost) all of the time (tout and bien), and others never being produced with liaison by any participants (voudrais, veux, après, etc). Note that we present here a binary vision of liaison, with the (target) consonant either being produced (1) or not (0); this type of analysis does not capture phenomena like pataquès where an alternative liaison consonant is realized. While this is not a major issue for the present data, which were produced from read texts, in spontaneous speech, a binary analysis of liaison might prove more limiting.

Figure 3. Proportion realised liaison by unique “word 1” context.

It is indeed the case that some of the words with the highest rates of liaison (tout, bien, est) occurred in the Civic World, which showed above-average rates of liaison when compared with the other worlds. Conversely, the World of Inspiration included some of the words with the lowest rates of liaison (moments, mots, difficultés, après). It is therefore likely that the higher rates of liaison in the Civic World are due to the (two) words that were nearly categorically realized with liaison (and which did not appear on trials in other worlds), and the lower rates of liaison in the World of Inspiration are due to the many words that appeared on those trials where liaison was never realized by any participants.

Nonetheless, there are striking patterns in the words that were more often produced with liaison and those that were less often produced with liaison. Many of the forms of the verb être, which are reported in the literature as showing the highest rates of variable liaison, indeed appear on the left side of Figure 3: est, sont, suis, c’est, c’était, soit. It is furthermore noteworthy that all of the plural nouns appear on the right side of the figure, in line with previous work showing relatively lower rates of realized variable liaison after plural nouns (e.g., Delattre, Reference Delattre1956; Côté, Reference Côté, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011; Pustka et al., Reference Pustka, Chalier and Jansen2017). With this in mind, we compared the rates of realized variable liaison in the present study with those reported in the corpus study of Pustka (Reference Pustka2017). That study looked at audiobooks for children and compared rates of realized variable liaison in different styles and registers, and appeared to us to be the most similar overall in terms of enunciative situation (i.e., actors reading prepared speech). Pustka (Reference Pustka2017) reports overall rates of realized liaison for 10 of our 24 unique liaison sites. Figure 4 shows a comparison between the rates of variable liaison realized in those 10 contexts in the present study compared to the rates reported in Pustka (Reference Pustka2017). The values reported in Pustka (Reference Pustka2017) and those observed in our production experiment are strongly correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.85).

Figure 4. Proportion realised liaison for the 10 contexts that appear in both the present study and in Pustka (Reference Pustka2017). The line is the regression line between the two series of values.

4. Discussion

Following recent work in perception, we tested the social meaning potential of variable liaison in spoken French using a production experiment. Focusing on the ideological dimension of social action within the framework of the pragmatic sociology of critique (Boltanski and Thévenot, Reference Boltanski, Thévenot and Porter2006, et seq.), Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Abbou and Burnett2023) showed that listeners in a perception task associated realized variable liaison with the value professionnalisme on trials in the Industrial World. The Industrial World is structured around a merit-based hierarchy, where efficiency and reliability are highly valued. The authors interpreted their finding by analysing realised liaison as an index to meanings of the written form that are valued in the Industrial World (notably the preparation that goes into a written text and the normative role of written language in France). In the present study, we used a production experiment and a subset of the same stimulus materials to test speakers’ use of variable liaison to convey professionalism. However, our participants did not appear to use the social meaning potential of liaison to perform our task, producing realized variable liaison at lexically-determined rates on a par with what has been found in previous (corpus) work.

The two findings thus appear to diverge. On the one hand, listeners are sensitive to the social meaning of liaison in perception, and on the other, speakers in our production task do not seem to exploit precisely this potential. This pattern is the opposite of what has been reported in previous studies comparing social meaning perception and production, which have tended to find a mismatch in the other direction (e.g., Squires, Reference Squires2013; Alderton, Reference Alderton2019; Hilton and Jeong, Reference Hilton and Jeong2019; Eddington and Brown, Reference Eddington and Brown2020).

It is important to keep in mind that the two tasks we compared are, despite their similarity, somewhat different in nature, beyond the modality of perception versus production. In the perception task, participants were presented with two guises. While the two guises were produced by different speakers, the (non-)realisation of the two liaison sites could potentially have drawn attention to this feature as something to focus on (and attention was in fact drawn to the production of liaison in the instructions given to participants). This would essentially reduce the task down to “is professionnalisme better conveyed with or without the realisation of liaison?”. In the production task, on the other hand, participants had every resource at their disposal (in addition to the [non-]realisation of liaison) to perform the characters and embody the target values. Other speech features like pacing, pitch, volume, are likely better (or at least sufficient) candidates compared to liaison to convey the intended meanings. This result highlights the difficulty in prompting speakers to exploit specific speech features to convey social meaning. Our production task also had the peculiarity of involving actors (both professional and amateur), and the style of speech that we elicit is thus rather different than what listeners might typically expect to hear. Given that the perception task was framed as an evaluation of voice actors, we think that the data from the two tasks are nonetheless interesting to compare.

Importantly, in contrast to previous work which tends to focus on social meaning as reflected by associations between linguistic forms and social groups, we analyse social meaning here that takes form through individual action as it plays out in the landscape of shared norms and values. That is, the social meaning of liaison, at least through the lens of a socio-pragmatic analysis, is not stratified in the same way as the social meaning of, for example, (ING) as studied by Campbell-Kibler (Reference Campbell-Kibler2006, et seq.). Eliciting socially meaningful uses of liaison (individual action) is thus a fundamentally different enterprise from analysing group-level patterns in a corpus. Future work on liaison production would undoubtedly benefit from further development of the acting game that we described here.

Liaison as a variable phenomenon has an additional particularity in variations that are actually attested. In the present article, we discuss variable liaison as a binary phenomenon, with a consonant being realized or not. However, pataquès, the production of a different liaison consonant than expected (e.g., trop realized with a liaison [z] as in [tʁozɛ̃pɔʁtɑ̃] rather than with the expected [p]) also occurs. Given its highly salient nature, fear of such forms might lead speakers to avoid certain liaison forms in some contexts, yielding different results in our production task than we might expect.

Finally, returning to the item-based results we observed, it seems likely to be the case that, on average, certain words are more or less likely to be produced with realized liaison. Indeed, lexical effects (e.g., word frequency) have been consistently noted when measuring liaison rates (see, e.g., Fougeron et al., Reference Fougeron, Goldman, Dart, Guélat and Jeager2001; Côté, Reference Côté, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011). In the case of a word that is not often realized with liaison (e.g., beaucoup), the realization of the liaison consonant by a speaker could thus draw attention on the part of the listener, pushing them to consider that the speaker might be trying to do more than convey the semantic content of the utterance (i.e., is attempting to convey additional, social, meaning). Determining the salience of a specific form can prove difficult given the different ways in which this concept can be operationalized (see, e.g., Bailey, Reference Bailey2019 and references therein), particularly in the absence of another variable to which it can be compared (e.g., the salience of realised liaison vs. the salience of ne omission). The stimulus items in the present study were designed to each contain one “more likely” liaison site (a form of the verb être) and one “less likely” liaison site (any other context), but future work could potentially specifically target highly frequent and very rare liaison contexts to work out to what extent surprisal might play a role in in-context meaning making.Footnote 9

5. Conclusion

Realization of variable liaison has been shown in a perception experiment to be interpreted by listeners as an effort on the part of the speaker to portray professionnalisme in social situations where efficacy and performance are key values. The fact that we did not observe speakers in the same situations producing higher rates of variable liaison highlights the delicate nature of social meaning associations. Realized variable liaison may very well lead to the perception of professionalism on the part of the listener, but this single linguistic variable’s link to such a social meaning does not appear strong enough to outweigh all other resources at a speaker’s disposal to convey so-called extra-linguistic meaning.

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding from the ERC under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement N°850539).

Declaration of competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.