Lutherans constituted the second largest Protestant group in the early modern Dutch Empire after the Dutch Reformed Church, the official denomination of the Dutch East and West India Companies (VOC and WIC). Lutherans came to the Dutch overseas territories as employees of the VOC and WIC and were predominantly of German and Scandinavian origin. Lutherans in Batavia in the East Indies, and Berbice, Curaçao and Surinam in the Americas received recognition in the 1740s and 1750s, but their counterparts at the Cape of Good Hope only gained religious freedom in 1780 due to resistance from the colonial government and Reformed authorities. This article analyses the changing relationship between the Lutheran community and the Reformed Church at the Cape of Good Hope from 1652 to 1820. The Reformed faith was the official religion under the VOC and retained its predominance until British rule in 1806. The Lutheran community sought recognition from the 1740s and grew to 1,000 members by 1776. In 1780 they were permitted to form a recognised congregation, becoming the only denomination with this privilege during Dutch rule. Scholars have viewed Cape Lutheran activity as a process of growing group consciousness that culminated in a separate Church.Footnote 1 This article argues instead that the Cape Lutherans had a more ambiguous relationship with their Church as they oscillated between the two denominations guided by personal preferences and the restrictions imposed on Lutherans by the Reformed authorities. Some Lutherans converted, whereas others upheld their faith at home or returned to the Reformed Church after sympathising with the Lutheran Church harmed their careers. As a result, Lutherans remained flexible in their religious affiliations until the early nineteenth century.

The evolving status of Lutheranism arose from local circumstances as well as the influence of Lutheran and Reformed support networks overseas. At the Cape, the Reformed Church endeavoured to maintain its dominance and persuaded the local government that unregulated Lutheran activity disturbed religious harmony in colonial society. The Lutherans meanwhile petitioned for recognition from 1742 and practised their faith in clandestine services and domestic worship. A group of families constituted the heart of this activism, and connected the larger Lutheran community to allies abroad. Both Protestant groups engaged ministers abroad to influence the position of the Cape Lutherans from afar. The Reformed Church mobilised the classis in Amsterdam to convince the Heren XVII, the directors of the VOC in the Dutch Republic, that Cape Lutherans should not receive recognition. The Cape Lutherans employed a similar strategy, encouraging the Lutheran Church in Amsterdam to intercede with the Heren XVII on their behalf. The activists also communicated with ministers from the Francke Foundations in Halle and its Danish-Halle Mission in India, and with Lutheran clergymen in the Dutch colonial city of Batavia. These foreign ministers advised on the petitions for recognition, organised clandestine religious services and supplied the community with books. Despite foreign assistance, Cape Lutherans received recognition nearly four decades later than their counterparts elsewhere in the Dutch Empire. This relatively late recognition was the result of local resistance by Reformed clergy and their influence within the Cape government. Meanwhile, Lutherans had to weigh the opportunities for clandestine worship provided by foreign ministers against potential damage to their social status. The decisions Lutherans made regarding their religious affiliations depended on their own wishes as well as the actions of other Protestant stakeholders at home and abroad.

The religious policy of the Dutch Republic has often been described as tolerant. This article invites the study of toleration and religious coexistence in the Dutch overseas territories. In contrast to the Dutch Republic, where the Reformed faith never became the state religion, territories under VOC control were subject to the Reformed Church, the official denomination of the Company. Recent scholarship has emphasised that the VOC actively promoted the Reformed faithFootnote 2 and sent nearly 1,000 ministers and several thousand lay-readers to the East Indies.Footnote 3 The second charter of the VOC, of 1622–3, argued for the continuation of the VOC monopoly to protect the Reformed faith.Footnote 4 The WIC similarly maintained a strong Reformed course in the Americas, as Danny Noorlander has shown, with the majority of its directors being full members of the Reformed Church who sat on ecclesiastical councils supervising religious policy in the colonies, most notably in Brazil.Footnote 5 The religious policy of the VOC included converting native peoples on Formosa, Ceylon and in the East Indies,Footnote 6 but equally targeted its European Catholic and Lutheran subjects. The VOC's stance towards the Lutheran populace, however, varied from territory to territory. The Cape developed a pattern of religious coexistence that differed from that in the Dutch Republic and the East Indies. In southern Africa, Lutheran life became characterised by religious mobility as Lutherans navigated between their restrictive local circumstances and the opportunities offered by contacts abroad. The Lutheran support network challenged, but did not overcome, the restricted social and religious position of Lutheranism in Dutch colonial society.

This article contributes to the scholarship on the role of Christianity among Europeans in the Dutch colonial world, and argues that behind the VOC's official Reformed façade lay a more religiously diverse European population which negotiated its status with the help of various branches of Protestantism, both locally and abroad. Drawing from new primary sources from ecclesiastical and institutional archives in South Africa, the Netherlands and Germany, this article identifies three phases of Lutheran interaction with the Reformed faith: a phase of compliance from 1652 to 1740, a phase of resistance from 1741 and a third phase from the 1780s until the early nineteenth century when Cape Lutherans secured recognition but increasingly returned to the Reformed Church.

Tacit compliance with the Reformed Church, 1652–1740

For the first ninety years of Dutch rule, most Lutherans tacitly accepted the privileged position of the Reformed Church. Lutherans had been present at the Cape since the foundation of a maritime replenishment station there in 1652, but could not hold separate services. They did not come forward as a group requesting recognition prior to the 1740s as the community was too small and, as one of the community leaders put it in 1742, in the previous ninety years there were not enough affluent members among the community to maintain a minister.Footnote 7 From the 1730s Germans formed the majority of newly arriving VOC employees and part of the community's older generation transitioned from the ranks of sailors and soldiers to become high Company officials and affluent landowners, reaching the social and financial standing that could warrant a request for a separate minister.

The Reformed Church strengthened Christian unity by accepting Lutherans into its congregation, but only if they adhered to Reformed principles. The first Reformed church council, installed in 1665 and acting under the supervision of the Amsterdam classis,Footnote 8 admitted Lutherans to communionFootnote 9 but the practice had apparently ceased by 1714 when several Lutherans requested the eucharist.Footnote 10 On the advice of the classis, the Reformed Church in Cape Town investigated their views on ‘essential parts of the religion’ first since ‘there are currently many hiding among the brethren of the Augsburg Confession who differ from us on more issues than just Holy Communion’.Footnote 11 During a formal examination, the church council and elders tested whether prospective members agreed with the Reformed view on justification. Unsurprisingly, this measure deterred the Lutherans, and initially none of them attended communion services any more.Footnote 12 Lutherans received the eucharist in Cape Town and the inland districts of Stellenbosch and Drakenstein only several years later.Footnote 13

Attending the communion service was not the same as becoming a member (lidmaat) of the Reformed Church. It was only possible to fully join after proving confirmation of faith (belijdenis), or submitting an attestation from a Reformed Church in Europe.Footnote 14 Not everyone at the Cape desired to subject themselves to these examinations or met the requirements. Less than half of the European population were church members,Footnote 15 a lower figure than that in the Dutch Republic.Footnote 16 A handful of Lutherans became members of the Reformed Church.Footnote 17 The most obvious motive was a genuine affinity with the Reformed faith. But for some Lutherans at the end of the seventeenth century, this was the only available form of Christian worship; a necessary evil, better than no worship at all. For most Lutherans, the Reformed faith played a central role in their lives upon marriage. As they had nearly all come to the Cape as single men and then married Reformed women, these immigrants joined their spouse's church to solemnise their marriages and baptise and catechise their children. Lutherans who joined in this way were seen as model integrators. By the early 1730s the Reformed Church was satisfactorily informing the classis that the Lutherans ‘listen diligently to the gospel and have educated their children in the true Reformed faith’.Footnote 18 As a result, the Reformed congregation in Cape Town had grown to 300 members, many of whom were Lutherans and their offspring.Footnote 19

Cape Lutherans were a heterogeneous group and modelled their religious affiliation around their preferences and liberties. While part of the Lutheran population converted, another group returned to Europe for religious reasons. In 1706 two ministers of the Danish-Halle Mission, Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg and Heinrich Plütschau, visited the Cape on their way to India and observed a group of Lutherans who did not practise their religion:

We hoped that we should have met with, among the Christians here, such Souls, as might have a true Hunger and Thirst after the Word of God; most of them being German Lutherans, left without a Minister: but hitherto we find little among 'em …. Everyone pretends he cannot serve God so well in these parts, as in his own Country; and so they think they had rather put it quite off, till they came home again.Footnote 20

The missionaries correctly deduced that part of the Lutheran population was unwilling to worship in the Reformed tradition, but mistakenly interpreted this as a lack of zeal. On the contrary, ‘many hundreds’ of Lutherans, as the German surgeon Christoph Frick stated in 1685, wanted to leave the Dutch East Indies just to practise their religion again.Footnote 21 Frick himself declined an advantageous alliance with the daughter of a Cape German for this reason and returned to Europe.Footnote 22 In the late eighteenth century nearly all of the militia and sailors at the Cape were Lutherans. Yet, according to one of the community leaders, Tobias Christian Rönnenkamp, many returned after their contracts expired in order to freely practise their beliefs.Footnote 23 In 1776 Rönnenkamp met August Schreiber from Holstein, who had sold his possessions and was about to leave the colony. Schreiber said he wanted to ‘serve the Lord’, which he had not been able to do at the Cape. With tears in his eyes, he confided to Rönnenkamp:

Truly, Sir! Believe me as an honest man – I want to spend all that I have on a minister, but we will never get one, those people [the Reformed] … are against it as you know; should I, now that I am old and alone, continue to live like a Beast, no! I will return to my country, and I wish I was already there, because I long to die a Christian, and I do not see any possibility to do so here.Footnote 24

Not all Lutherans who wished to return were able to do so. Practical reasons, fear of the dangerous return voyage and rumours about a lack of employment in the German lands dissuaded Lutherans from leaving.Footnote 25 As a result, a third group of Lutherans, who settled in the colony permanently, integrated both faiths into their lives. This group attended services in the Reformed Church while they practised their Lutheran faith in the domestic sphere.Footnote 26 It was this group of Lutherans that began the petitions for recognition towards the mid-eighteenth century.

Resistance, 1741–79

The Lutheran population of the seventeenth-century Cape had been small and unorganised. During the eighteenth century, migration from the Holy Roman Empire to the Cape soared. The Lutheran populace increased from 509 individuals in 1741Footnote 27 to ‘at least 1,000’ in 1776, excluding the dispersed inland population.Footnote 28 The steady immigration also added arrivals who were not yet incorporated into the Reformed Church. In the 1740s and 1750s Lutherans in other parts of the Dutch Empire received recognition, and in 1741 the Danish king, at the suggestion of the Danish-Halle Mission,Footnote 29 asked the Dutch States-General to extend this religious freedom to the Cape Lutherans. The growing Lutheran presence and formation of Lutheran congregations elsewhere in the Dutch Empire spurred an elite group to petition for recognition. This delegation initially consisted of Company officials, burghers and artisans, but soon the group decided to include the signatures of lower-ranking individuals such as soldiers as well.Footnote 30 The delegation drew support from a community diverse in geographical and socio-economic backgrounds: Company officials from the city, farmhands and landowners in rural districts, and itinerant sailors and soldiers. In 1742 the delegation submitted their first request for recognition to the local government. They asked for their own minister to ‘freely practise their religion’Footnote 31 ‘in the same way as has been allowed in the United Netherlands’.Footnote 32 The demand for equality aimed at imperial equality with Lutherans under Dutch control, rather than equality with the Reformed.Footnote 33

It took longer to realise equal religious coexistence at the Cape than in other Dutch overseas territories. Cape Lutherans received formal freedom of religion together with Batavia in 1742 to make the territories attractive for a larger number of Europeans.Footnote 34 While the decree took effect in Batavia, local resistance from the Reformed clergy and their contacts within the government delayed implementation of the proclamation in southern Africa. Governor Hendrik Swellengrebel (s. 1739–51) and his successor Ryk Tulbagh (s. 1751–71) were brothers-in-law to the Reformed minister François le Sueur, who actively campaigned against the Lutheran cause. According to a contemporary tale, Tulbagh maintained that he would never authorise a Lutheran church ‘as long as he still had one eye open’.Footnote 35 Swellengrebel, in contrast to Tulbagh, sympathised with the petitioners, but tempered his support with his family relationship to Le Sueur. Swellengrebel initially met the Lutheran delegates in private, but their conversations remained moot. He confessed that he could personally tolerate a Lutheran minister, but was not willing to convince the Heren XVII since counterparts in the Dutch Republic suspected him of sympathising with the Lutherans.Footnote 36 Swellengrebel permitted the petitioners to send their request to the Heren XVII for consideration, but could do little to sway government opinion towards religious freedom. Besides backing by the governors, the Reformed Church also found support with the Amsterdam classis which lobbied the Heren XVII on their behalf.Footnote 37 The local Reformed clergy and their connections in the Dutch Republic were fundamental in delaying religious freedom at the Cape. The first Lutheran petition of 1742 and the subsequent petitions submitted in 1743, 1751 and 1753 all proved unsuccessful.

Cape Lutherans established their own support network with ministers in Amsterdam, Halle, Tranquebar and Batavia throughout the eighteenth century to aid their restricted position. Established Lutheran Churches in Amsterdam and Batavia acted as advisors. The Francke Foundations in Halle were a centre of Pietism, an influential movement within the wider Protestant population at the Cape towards the late eighteenth century. A few colonists came into contact with the Francke Foundations in Europe and maintained ties with them after moving to southern Africa. Ministers of the Danish-Halle Mission visited the Cape en route to Tranquebar in India. Ministers in these four places supplied the Cape Lutherans with books, provided pastoral support and instructed them on how they should petition for freedom of religion. The core of this network was a group of Cape Lutheran activists who enabled religious activity for the larger community. The Dutch immigrant Johannes Needer, a leading figure in the 1740s, corresponded with ministers in Amsterdam and organised large-scale Lutheran book imports.Footnote 38 Cape Lutherans corresponded most intensely with the Lutheran Church in Amsterdam. Contacts began in 1741 on the initiative of Cape Lutherans, followed by an official correspondence a year later. Amsterdam lobbied the Heren XVII, searched for suitable clergymen for the Cape congregation and informed them of the status of coreligionists elsewhere in the Dutch Empire. A group of mainly German-speaking families maintained contacts with German Lutheran ministers of the Francke Foundations and the Danish-Halle Mission. The Francke Foundations and the Danish-Halle Mission supplied books and maintained direct links with followers of German Pietistic traditions within the Lutheran population. Contacts in Batavia informed Cape Lutherans about their counterparts in the largest Dutch settlement in Asia. Batavians sent copies of their minutes and resolutions, and the Lutheran pastor Jan Brandes, who assumed his post in 1778, exchanged letters with his friends in southern Africa. Besides his letters to the Lutheran minister Andreas Lutgerus Kolver, he also advised Rönnenkamp on church matters such as the baptism of children from Reformed-Lutheran families.Footnote 39 These connections with ministers abroad proved vital in sustaining Lutheran activism at the Cape during the period of unsuccessful petitioning and resistance.

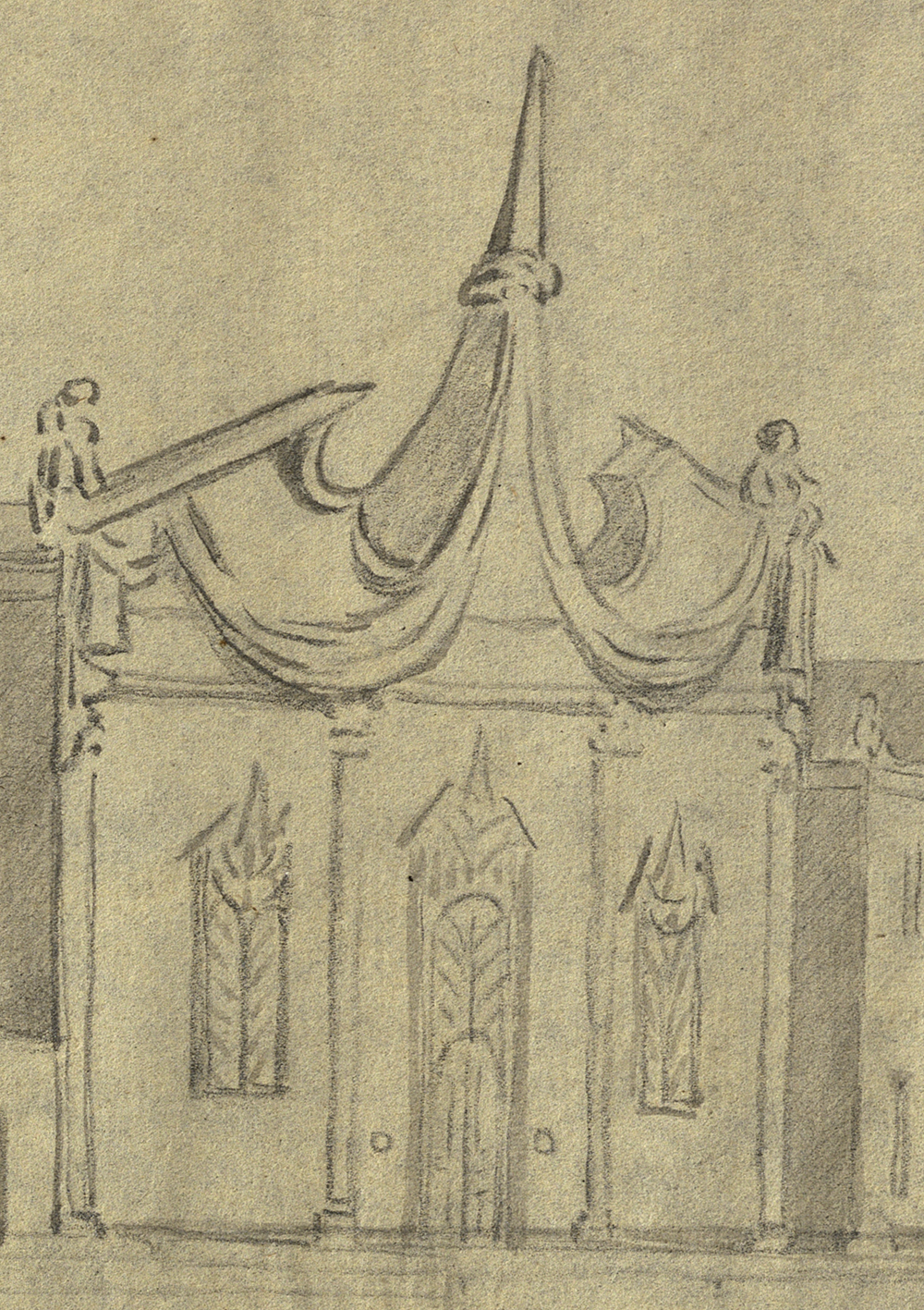

Contacts with foreign ministers also enabled clandestine Lutheran activity.Footnote 40 As consecutive unsuccessful petitions left the Lutherans without a church for longer than anticipated, the community organised unofficial services whenever suitable clergymen visited the Cape. The first to hold group worship was Georg Schmidt, a missionary of the Moravian Church, who evangelised the African Khoekhoen population from 1737 to 1744.Footnote 41 Schmidt regularly visited Lutherans for pastoral care and organised small-scale gatherings.Footnote 42 From the 1730s, Cape Lutherans asked ministers travelling to or from Asia to lead religious services. These ministers were chaplains of the Danish and Swedish East India Companies, missionaries of the Danish-Halle Mission and Lutheran ministers destined for Batavia. The ministers preached, administered communion and confirmed new members. In 1776 between 800 and 900 people attended a service organised by a visiting minster, and more than 300 received communion.Footnote 43 The services initially took place in the houses of prominent Lutherans, who converted a room into a place of worship.Footnote 44 The community congregated in a building that resembled a proper church from 1776 when the affluent wine producer Martin Melck and his wife Anna Margaretha Hop bequeathed to the community a building which was provisionally disguised as a wine storehouse, but had the interior of a church (see Figure 1).Footnote 45 The Lutheran services held there and in other private establishments were not genuinely clandestine. The government begrudgingly allowed Lutheran services as long as they were conducted by visiting ministers and therefore occurred infrequently. The ministers also first had to obtain the governor's permission.Footnote 46 By allowing intermittent worship, the government could keep the community subordinate to the Reformed Church. While such clandestine services sustained Lutheran activity, they inadvertently gave the government a reason to postpone religious freedom.

Figure 1. The clandestine Lutheran church, c. 1777: Johannes Schumacher, ‘View of Cape Town’ (detail). Reproduced by kind permission of the Swellengrebel Archive, St Maarten (NL), F I-60.

The Lutheran petitions, book distributions and clandestine services eroded the initially peaceful relations between the Lutherans and the Reformed Church. In 1750 the Reformed Church observed the ambiguous religious affiliations among the Lutherans and wondered whether those ‘who, in all respects, stay true to their own teachings’ may receive communion.Footnote 47 The Amsterdam classis wanted to prevent hostile relations between the two denominations and recommended that Lutherans should still receive the eucharist.Footnote 48 The Reformed Church and Cape government also preferred united worship as they believed a separate Lutheran Church would deepen the growing confessional and societal divide. The Reformed Church argued that granting the Lutherans religious freedom would lead to discord within mixed confessional families.Footnote 49 The Church was also concerned that its membership would decline if children were raised in the religion of their Lutheran fathers.Footnote 50 Otto Friedrich Mentzel, a German VOC official who lived at the Cape in the 1730s, confirmed:

All Christian children born in this country are baptised and taken into the Reformed Church. Nevertheless, should a Lutheran Evangelical Church be set up and a minister appointed, I have no doubt, that all descendants of Lutherans, who had not yet become communicants of the Reformed Church would become members of the Lutheran Church, and the Reformed Congregation might then number little more than a third of the whole community.Footnote 51

The growing Lutheran zeal in the colony particularly alarmed the Reformed Church as it contrasted with the limited devotion of some Reformed churchgoers. Until the late eighteenth century, the Cape was not an exemplary religious society. Membership of the Reformed Church was not mandatory: around 1700, only 8 per cent of the free adult population of Cape Town were church members and in Stellenbosch membership fluctuated between 16 and 27 per cent from 1695 to 1726.Footnote 52 When the Reformed VOC minister François Valentyn visited the Cape in 1714, he observed that only forty men and forty-eight women attended the communion service. No official from the Cape government took part in the service, nor were any of them church members. He feared that ‘inland it may not be expected to be one-half so good’, and concluded that the local clergymen had made little progress among the inhabitants, ‘due in no wise to faltering of their zeal, but to the stupidity and indolence of the Burghers. I perceived also, that there are many Lutherans among the Servants’.Footnote 53 When Gustaaf Willem Baron van Imhoff, governor-general of the Dutch East Indies, conducted an official inspection of the Cape in 1743, he concluded to his amazement that the colony was a ‘congregation of blind heathens rather than a colony of Europeans and Christians’.Footnote 54 In response to Van Imhoff's recommendations, the government built new churches in the inland districts, but the Reformed church councils continued to lament the limited devotion and disinterest of its members.Footnote 55 The Cape government, too, was concerned about the state of the Reformed religion in the colony and issued decrees against drinking, working and selling goods on Sundays.Footnote 56 Such official complaints about a perceived lack of religious zeal were, of course, by no means unique to the Cape and can be found in contemporary sources in Europe and North America. They also have to be interpreted as sources produced by clergy and officials in favour of extending the prominence of Reformed Christianity. Still, in the case of the Cape, these statements reflect a contrast in engagement between the Reformed and Lutheran communities. It was only towards the end of the eighteenth century that a religious revival brought about a rise in domestic piety, especially among the Reformed.Footnote 57

There was an additional reason why the Reformed Church wanted to prevent a Lutheran minister from taking office. The Lutheran populace was overwhelmingly non-Dutch, consisting mainly of Germans and a few Scandinavians. Congregants sang in GermanFootnote 58 and held religious services in Dutch or German.Footnote 59 When a church was finally opened, 81 per cent of its members were German immigrants.Footnote 60 The Reformed Church may have wanted to prevent these immigrants from nurturing a separate national and linguistic identity.Footnote 61 The Reformed Church therefore closely watched the contacts of the Lutheran community with foreign ministers who could sustain beliefs from the migrants’ places of origin. As we have seen, the Lutherans had strong connections with the Francke Foundations and the Danish-Halle Mission. The Reformed Church condoned services led by Hallensian ministers and had noticed a few Lutheran books circulating in the colony, which they suspected Halle had provided.Footnote 62 Yet the Church did not know that the connections with Halle and its mission went even deeper as the spiritual support in letters and the majority of the regular book supplies escaped the eyes of the Reformed authorities.

The superficial knowledge that the Reformed Church and local government had gathered about the Cape-Halle-Tranquebar network was nevertheless sufficient to object to a minister with contacts to the Francke Foundations. The Lutherans had their eyes set on a candidate from HalleFootnote 63 and proposed Christiaan Frederik Blettermann, the son of a German immigrant and alumnus of the Francke Foundations’ Latin school, who was now minister in his father's native town of Sondershausen.Footnote 64 The Cape Lutheran Daniel Gottfried Karnspeck, who had briefly studied theology at the University of Halle,Footnote 65 also expressed his wish to fill the post in the name of the Danish-Halle Mission.Footnote 66 The Reformed Church, however, stated that they would rather have a Dutch-born pastor, and certainly not a Dane or another foreigner to ‘maintain peace between us and our brethren [Lutherans]’.Footnote 67 Governor Joachim van Plettenberg (s. 1774–85) and the Heren XVII, too, only wanted a Dutch-born pastor.Footnote 68 The authorities realised that the Christian community could factionalise if a future Lutheran Church united foreign nationals and their faith under one roof. The government and Church therefore wanted to avoid installing a Lutheran pastor who was affiliated with Halle and its mission, someone who could only fuel connections with the Holy Roman Empire.

Establishment of a Lutheran Church and return to the Reformed Church, 1780–1820

Cape Lutherans received recognition in 1779 and inaugurated their church the next year. Governor Tulbagh's death in 1771 and the completion of the storehouse-church had sparked renewed incentives to petition for recognition. This time the Lutherans employed a different strategy. The Lutheran Church in Amsterdam directly approached the Heren XVII without informing the Cape government. The Reformed authorities in Cape Town and Amsterdam were therefore unable to appeal to the Cape government and the Heren XVII. The Heren XVII provisionally granted the Cape Lutherans freedom of religion, which translated into an official charter after the Cape government consented in 1779. The Lutheran Church in Amsterdam nominated the Dutch pastor Andreas Lutgerus Kolver, and the congregation formed a church council and appointed deacons and elders. With the inauguration of the church came full recognition, but not complete equality of Lutheran citizens. Rather, the opening of the church posed new challenges. Disagreements arose between the Churches over baptism and the church building, and Lutherans started to be excluded from high government positions. As a result of these disagreements, increasing numbers of Lutherans returned to the Reformed Church in order to secure career prospects for their families.

Recognition of the Lutheran faith entailed greater visibility of the community, which both the Cape government and the Reformed Church tried to counter. The authorities did not want the church building to underline the public presence of the community and vie for hegemony with the Reformed Church in Cape Town's architectural landscape. This created tension when the Lutherans laid out their plans to elevate the storehouse to a proper church. While the Lutheran church in Batavia was hidden behind a wall and trees, the Cape Lutherans envisaged a church that would make ‘a visual statement of its importance’.Footnote 69 Yet they were not allowed to enhance the building with an altar, pulpit, tower, spire, clock or bells.Footnote 70 The building was therefore deceptively modest from the outside, with subtly sculpted swags adorning the front façade that joined a small steeple (see Figure 2). The design and execution of the façade were the work of the German sculptor Anton Anreith.Footnote 71 Foreign sojourners remarked how strange they found a church with an elaborate façade, rather than a spire. Visitors variously described the exterior as ‘a short pyramid’ with ‘voluminous festoons’ and ‘three or four chubby figures … perched … rather clumsily on the roof’.Footnote 72 This unconventional façade was removed during maintenance work in 1818–20, and was replaced by a clock tower, now permitted under the religiously more lenient British rule (see Figure 3).Footnote 73 The initial architectural restrictions prompted the Lutherans to concentrate on the interior, for which Anreith constructed a grand wooden pulpit with two figures of Hercules supporting the stage which emphasised the significance of their church as the only recognised denomination besides the Reformed Church. The Lutherans employed architecture to demonstrate pride in their recognition as much as to contest their still inferior status.

Figure 2. The Lutheran church, 1797: Lady Anne Barnard, ‘The Lutheran church in Cape Town’ (detail), National Library of South Africa, Cape Town, MSB 68, INIL 7058. Reproduced courtesy of the National Library of South Africa: Cape Town campus.

Figure 3. The Lutheran church tower from 1818: Arthur Elliott, ‘The Lutheran church in Cape Town’ (detail), early twentieth-century photograph, WCARS, E 7934. Reproduced by kind permission of the Western Cape Archives, Cape Town.

Career prospects for Lutherans worsened as their wish for recognition became more pronounced. Lutherans had initially obtained high posts in governmentFootnote 74 but this changed towards the 1770s when it became an informal requirement for Company officials to be Reformed.Footnote 75 Some Lutherans converted in order to secure positions, such as Otto Lüder Hemmy, a high Company official and elder of the Lutheran community who converted in 1776,Footnote 76 three years after his promotion to vice-governor.Footnote 77 Lutherans who anticipated that their employment would suffer did not attend the Lutheran church after its inauguration, and the community shrank from 1,000 adherents in 1776 to 441 in 1780.Footnote 78 The membership list of the 1780 congregation includes only four people who had signed the first petition of 1742, and nine descendants of the original signatories. The remaining signatories had been unable or unwilling to pass on their religion to their children, or had returned to Europe.Footnote 79 In the 1780s new regulations came into place that excluded Lutherans from government positions. The Heren XVII decided that no Lutheran could serve on the Councils of Policy and Justice and no more than half of the lower councils should be made up of Lutherans.Footnote 80 Seven officials lost their positions or were no longer considered for positions because of their faith.Footnote 81 Unlike the previous decades, when the pragmatic Cape government accepted the non-Reformed into senior posts, after recognition of the Lutheran faith the Heren XVII successfully enforced their exclusion from the highest echelons of the colonial administration.Footnote 82 For as long as Dutch rule continued, being Reformed was the precondition for a career in government, which prompted Lutheran families to return to the Reformed Church.

Lutherans also returned to the Reformed Church so long as they were not allowed to baptise or confirm their children in their own faith. Cape Lutherans were theoretically subject to the same regulations as their coreligionists in Batavia, which stipulated that daughters had to be baptised in the Church of their mothers and sons in the Church of their fathers. Parents could also baptise their children into the Reformed Church regardless of the infant's sex, but not into the Lutheran Church.Footnote 83 The Reformed Church was initially unaware of these regulations, hence the Lutheran pastor baptised as he pleased. As the Reformed authorities acquainted themselves with the Batavian regulations in 1782, they objected that the Lutheran pastor had unlawfully baptised the daughter of a Lutheran father and Reformed mother, and had confirmed four children.Footnote 84 The Lutheran church council argued that they had been granted freedom of religion on the same conditions as the Lutherans in Amsterdam and Batavia. In these cities couples could baptise their children in the Church they preferred, whether it be Lutheran or Reformed.Footnote 85 But the Lutherans knew they strained the truth. They had been advised by their friend Jan Brandes, Lutheran minister in Batavia, who welcomed any new member who had been sufficiently instructed in the Lutheran faith. ‘Your church disputes are truly saddening & very tricky. We are not watched so intensely here’, Brandes wrote to Rönnenkamp, a Lutheran elder in Cape Town.Footnote 86 Brandes wrote he had not baptised a daughter of a Lutheran father yet, but had heard it was subject to a fine of 300 to 500 rixdollars.Footnote 87 The minister stressed that his friends at the Cape should maintain good relations with the Reformed, as ‘a religious war with the dominant denomination is somewhat hard to endure’.Footnote 88 The Lutheran Church in Amsterdam, however, did not see any confirmation from Batavia that Brandes's baptismal practices were lawful.Footnote 89 From 1783 Lutheran baptisms in Cape Town became subject to stricter control and the church council had to present a list of christenings that year.Footnote 90 Meanwhile, the Heren XVII investigated whether the regulations were still in force in Batavia, to which they received an affirmative response. The matter was finally settled with a novel solution in 1786. While the Cape had to follow the same rules as Batavia which meant that Lutherans could not baptise daughters of a Lutheran father and a Reformed mother, new members could be confirmed from the age of eighteen.Footnote 91

The rule of the VOC at the Cape came to an end in 1795. The following short periods of British (1795–1803) and then Dutch rule (1803–6) marked a new phase of religious tolerance. During British rule, the Lutherans baptised freely, and they could serve in government without restrictions.Footnote 92 When the Cape fell into Dutch hands again between 1803 and 1806 under the rule of the Batavian Republic, the new commissioner-general Jacob Abraham Uitenhage de Mist introduced a church order that perpetuated religious freedom as it proclaimed religious parity of all denominations.Footnote 93 This new church order echoed the religious reforms of the Batavian Republic (1795–1806), where all denominations received legal equality in 1798 and non-Reformed citizens were admitted to public office. The Reformed Church was no longer privileged.Footnote 94 However, the improved legal position of the Cape Lutheran congregation under Batavian rule could not prevent a decline in membership. The church council observed that the children of their most eminent members had returned to the Reformed Church for baptism and catechesis.Footnote 95 By 1805 the number of members had stagnated.Footnote 96 The Lutheran minister, Christian Heinrich Friedrich Hesse (s. 1800–17), deduced that the decree that VOC employees had to be Reformed still showed effect, and the disputes over baptism between the two Churches hampered further growth. In addition, most families in the rural districts lived closer to a Reformed church. The pastor estimated that there were not more than twenty families of which all members were Lutheran.Footnote 97 Hesse penned his observations when the Cape had grown from a small maritime replenishment service into an expanding colony. Migration into the frontier regions meant that by the turn of the nineteenth century, some colonists lived several hundred kilometres from Cape Town, and had to travel up to multiple weeks to reach the city.Footnote 98 As a result, Lutheranism became an overwhelmingly urban movement. In 1792 there were 459 Lutherans in Cape Town, but only fifteen resided further inland. The Reformed population, by contrast, numbered 641 members in the city and 1,408 outside of Cape Town.Footnote 99 Hesse's statements also reflect a change in zeal among the Lutheran population which indicates that their distance from the Lutheran Church was not only geographical but also emotional. Hesse lamented in 1815 that ‘the indifference of the congregation had long ago caused many of them, which were formerly considered as of the greatest importance, to be abandoned, and that, if the minister were entirely to relax in the performance of his duties, it would give to most of them very little concern’.Footnote 100 Hesse, an alumnus of the Francke Foundations’ Latin School and a theology graduate of the University of Göttingen,Footnote 101 was the type of candidate whom Cape Lutherans a generation earlier so longed for. Instead, Hesse signalled the evolving religious affiliations of his church members. Although Lutherans now had free choice over which church they attended, they succumbed to practical and career-driven motivations to secure their livelihoods. A growing number of Lutherans had returned to the Reformed Church to complete their integration into Cape society.

Lutherans at the Cape of Good Hope adapted their religious activities to the changing religious and political climate. Lutherans chose whether they worshipped in the Reformed or Lutheran tradition out of a strategic imperative as much as personal preference. During the first decades of Dutch rule, Lutherans either returned to Europe for religious reasons or worshipped in the Reformed Church. These churchgoers could be only nominal members of the Reformed Church and uphold their Lutheran faith clandestinely. From the eighteenth century, many Lutherans attended irregular clandestine services while they took part in Reformed services for the rest of the year. Once the Lutherans opened their church in 1780, the congregation shrank as an increasing number of families returned to the Reformed Church to secure their career prospects. The Protestant population of the early modern Cape cannot therefore be easily divided into Lutherans and Reformed. Instead, Lutherans alternated between compliance and resistance.

In their religious behaviour, Cape Lutherans were influenced by local authorities as well as allies abroad. The Lutheran support network overseas challenged the restricted position of the Cape Lutherans and provided them with alternative ways of worship. Recommendations by foreign ministers were instrumental in crafting and planning the petitions and the lobbying by the Lutheran Church in Amsterdam eventually secured the religious recognition of Lutherans in southern Africa. Meanwhile, books and occasional services that the foreign ministers offered helped to bridge the period of absence of a church. Despite help from abroad, Cape Lutherans were realists and negotiated their position in an intra-imperial Dutch model and asked for recognition, not for religious parity. Yet the connections that invigorated Lutheran activism at the Cape also increased hostility between the community and the Cape authorities. The Lutheran network sustained the foreign German-Lutheran identity of the community, and the petitions eroded the civil relations between the two denominations. When the Lutherans secured recognition, their institutional success did not equate to an improved social position. On the contrary, their career opportunities diminished and Lutheran baptisms became subject to governmental control. These restrictions prompted Lutherans to return to the Reformed Church. Towards the end of Dutch colonial rule, the religious lives of Cape Lutherans became increasingly intertwined with their local Reformed environment.

The early modern Cape of Good Hope exemplifies that Protestants in the Dutch Empire forged ties with allies in Europe as well as Protestants in other colonies. Support from Christians elsewhere could extend to include other Protestant groups and missionary societies with similar interests. The Cape Lutheran community absorbed elements of Moravian and Hallensian Pietism as well as of Dutch Lutheran traditions. The example of the Cape Lutherans also shows how local circumstances could still be decisive in determining the status of Christian groups. These Protestants adapted to the new religious environment of their host society, but were flexible in the exercise of their faith depending on the degree of government intervention, and the power of religious institutions over the European population. The social status of their denomination, local opportunities and potential legal and social restrictions all conditioned whether Protestants beyond Europe stayed loyal to their Church.