Introduction

Caregivers’ extratextual talk (verbal deviations from the print) during shared-book reading is a stronger predictor of preschoolers’ vocabulary skills than frequent reading (Roberts, Jurgens & Burchinal, Reference Roberts, Jurgens and Burchinal2005; Zucker, Cabell, Justice, Pentimonti & Kaderavek, Reference Zucker, Cabell, Justice, Pentimonti and Kaderavek2013). One aspect of the extratextual talk considered especially beneficial for language development in the preschool years is the more challenging, abstract talk (also known as decontextualized, inferential, high-demand, and non-immediate talk). Such talk – connecting the book to the child’s life, predictions, and explanations – contrasts with concrete language such as labelling and describing the pictures, and predicts vocabulary and emergent literacy skills into the school years (DeTemple, Reference DeTemple, Dickinson and Tabors2001; Dickinson & Porche, Reference Dickinson and Porche2011; Dickinson & Smith, Reference Dickinson and Smith1994; Hindman, Connor, Jewkes & Morrison, Reference Hindman, Connor, Jewkes and Morrison2008).

Why does abstract talk during shared reading predict preschoolers’ language development? Abstract (versus concrete) talk tends to be more complex in terms of its syntax and vocabulary (Curenton, Craig & Flanigan, Reference Curenton, Craig and Flanigan2008; Demir, Rowe, Heller, Goldin-Meadow & Levine, Reference Demir, Rowe, Heller, Goldin-Meadow and Levine2015). For example, making inferences and providing explanations often involve complex constructions (e.g., “he hid because he was scared”) and mental state and linguistic verbs (e.g., “he thinks the fox is coming”). Abstract talk also provides rich information about referents (e.g., “sharks have sharp teeth so they can catch their prey”) versus simply labelling (e.g., “that’s a shark, look at its teeth”). Thus abstract talk provides children with the opportunity to learn a more diverse syntax and vocabulary, and can strengthen semantic networks (Blewitt, Rump, Shealy & Cook, Reference Blewitt, Rump, Shealy and Cook2009).

Another way that abstract talk might influence children’s language skills is through the extended, child-involved style of discourse that it tends to engender in certain contexts. For example, research on language use with young children during mealtimes has documented that explanations and narratives (two kinds of abstract talk) often extend over multiple speaker turns, involving the caregivers asking questions and following up on children’s responses to extend the conversation (Snow & Beals, Reference Snow and Beals2006). Similarly, in the reminiscing literature, some caregivers are shown to use an elaborative style (characterized in part by questions and follow ups that extend the conversation) when talking about the past with their young children, which is shown to predict language development (e.g., Reese, Leyva, Sparks & Grolnick, Reference Reese, Leyva, Sparks and Grolnick2010; for a review see Salmon & Reese, Reference Salmon and Reese2016). Explanatory talk during readalouds in kindergarten classrooms is also shown to involve discussions over multiple speaker turns (Gosen, Berenst & de Glopper, Reference Gosen, Berenst and de Glopper2013; Mascareño, Snow, Deunk & Bosker, Reference Mascareño, Snow, Deunk and Bosker2016), and preschool teachers’ child-involved analytic talk is more predictive of children’s vocabulary growth than other features of the talk, such as immediate recall and feedback (Dickinson & Smith, Reference Dickinson and Smith1994). From a social-interactionist view (Peterson & McCabe, Reference Peterson and McCabe1994; Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978), such talk is likely to benefit the child’s developing language skills not only because of the abstract/concrete content of individual utterances, but also and perhaps more importantly because of its interactive and co-constructive nature.

Previous research has tended to focus on the overall amount or level of abstraction during shared reading and its relation to children’s language development. This approach typically indexes the level of abstraction by counting the number of utterances that are abstract. A limitation of this approach is that it does not consider utterance function (e.g., questions, statements) or the overall style of the extratextual talk (e.g., to what degree it supports the child’s involvement and the co-construction of meaning). In light of this, some researchers have reasoned that abstract questions might be especially beneficial for preschoolers’ language development (Massey, Pence, Justice & Bowles, Reference Massey, Pence, Justice and Bowles2008; Zucker, Justice, Piasta & Kaderavek, Reference Zucker, Justice, Piasta and Kaderavek2010). It is in fact well documented that questions, and in particular wh-questions (e.g., what questions), predict toddlers’ language development (e.g., Cristofaro & Tamis-LeMonda, Reference Cristofaro and Tamis-LeMonda2012; Rowe, Leech & Cabrera, Reference Rowe, Leech and Cabrera2017). Furthermore, as children get older, parents and teachers ask them more challenging or abstract questions (e.g., why questions) during shared reading (Deshmukh, Zucker, Tambyraja, Pentimonti, Bowles & Justice, Reference Deshmukh, Zucker, Tambyraja, Pentimonti, Bowles and Justice2019; Tompkins, Bengochea, Nicol & Justice, Reference Tompkins, Bengochea, Nicol and Justice2017).

However, there is no strong evidence that abstract questions are especially beneficial for vocabulary development. Zucker et al. (Reference Zucker, Justice, Piasta and Kaderavek2010) found no association between inferential (abstract) questions during classroom based shared reading on preschoolers’ vocabulary skills 4 weeks later, although there was a non-significant trend toward such questions being beneficial for children with higher initial skill. More recently, Tompkins et al. (Reference Tompkins, Bengochea, Nicol and Justice2017) found that mothers’ inferential yes/no questions and statements during shared reading predicted preschool-age children’s vocabulary skills 6 months later, whereas inferential wh-questions and literal utterances of any function did not.

We take a different approach to that of previous research and suggest that the overall style of the extratextual talk might be more important for preschoolers’ language development than the level of abstraction. Our paper addresses a recent call for researchers to examine the input during shared reading along multiple dimensions (for example, not only its level of abstraction but also its degree of interactivity) to determine which aspects of the input are most important for children’s vocabulary growth and why (Rowe & Snow, Reference Rowe and Snow2020). Based on the existing literature (for a recent summary see Rowe & Snow, Reference Rowe and Snow2020), we define an interactive style of extratextual talk for preschoolers as one that is characterized by questions and follow ups that appraise and elaborate on children’s responses to extend the conversation. We expect that a highly interactive style of extratextual talk will provide a supportive context for abstract discussions to unfold during shared reading with preschoolers, and thus predict language outcomes above sheer level of abstraction.

Importantly, a highly interactive style of extratextual talk is not necessarily high in its level of abstraction. An example of a highly interactive reading style that is largely concrete is the well-known Dialogic Reading approach, which has been shown to improve toddlers’ language outcomes (e.g., Whitehurst, Arnold, Epstein, Angell & Fischel, Reference Whitehurst, Arnold, Epstein, Angell and Fischel1994). Similarly, a mother who uses lots of abstract extratextual talk might not necessarily support her child’s participation in the discourse by using a highly interactive style. Thus level of abstraction and interactivity can be considered separate dimensions of extratextual talk. However, these separate constructs may be related, in that interactivity may support or provide a platform for abstract discussions to unfold. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the relation between these two dimensions of the extratextual talk, and their role in children’s vocabulary skills in the shared-reading context.

Our goal was to investigate the relation between mothers’ level of abstraction and interactivity during shared reading, and their role in preschoolers’ vocabulary development. Thirty-five mother-child dyads were video-recorded during shared reading in their homes, and child vocabulary skill was measured both concurrently and 1 year later. First, we hypothesized that the level of abstraction would be positively associated with a more interactive reading style. Second, we hypothesized that both the level of abstraction and interactivity in mothers’ extratextual talk would predict children’s concurrent and later vocabulary skills, but that interactivity would be a stronger predictor of these skills.

Research questions:

RQ1. To what degree is the level of abstraction related to use of an interactive reading style during shared reading?

RQ2. Controlling for SES, child age, and the amount of extratextual talk, what are the contributions of the level of abstraction and interactive style to variance in children’s concurrent vocabulary skills?

RQ3. Controlling for SES, child age, the amount of extratextual talk, and children’s earlier vocabulary skills, what are the contributions of the level of abstraction and interactive style to variance in children’s later vocabulary skills?

Method

Participants

Thirty-five mother-child dyads (13 boys and 22 girls) participated in the present study. This sample was a subset from an earlier, larger observational study (Muhinyi, Hesketh, Stewart & Rowland, Reference Muhinyi, Hesketh, Stewart and Rowland2020). Participants were recruited from Greater Manchester in the United Kingdom. On visit 1, children’s ages ranged from 36 to 59 months (M = 46.3, SD = 6.7). Raw scores on the British Picture Vocabulary Test (BPVS-II; Dunn, Dunn, Whetton & Burley, Reference Dunn, Dunn, Whetton and Burley1997) ranged from 40 to 87 (M = 63.0, SD = 12.3). Standard scores on the BPVS ranged from 91 to 138 (M = 111.29, SD = 11.15), indicating that as a group children’s vocabulary skills were above average. Twenty-seven of the children were White, 6 Mixed-race, 1 Asian, and 1 Black. Table 1 shows participant SES and frequency of home reading as reported by mothers. Most dyads were frequent readers, and most read books together more than four times a week. English was the home language for all families. Thirty mothers (85.7%) had at least an undergraduate degree or equivalent, three (8.6%) had at least A levels or equivalent (equivalent to a US high school diploma in the US), two (5.7%) had at least 5 GCSEs (a general educational development credential, usually obtained at the end of the period of obligatory education between 14 and 16 years of age).

Table 1. Home Reading Frequency and Socioeconomic Status

Note. N = 35. IMD = Indices of Multiple Deprivation (Education, Skills, and Training Deprivation deciles; 10 = least deprived). Percentages may not equal 100 because of rounding.

Procedure

Data were collected on an initial home visit and then 1 year later on a second home visit. Participants were asked to read the books as they normally would. Written informed consent was obtained from the mother. Demographic information was collected by a questionnaire. On the initial visit, the researcher played the Pop up Pirate game with the child, before assessing their language skills. Dyads were then videoed sharing two of four age-appropriate and commercially available stories, all of which had scope for abstract discussions about the story. Of those two books each dyad shared, one had a false-belief and one did not. The books were all unfamiliar to dyads, and the false-belief books (and the non-false belief books) were very closely matched in terms of linguistic and visual features, and yielded comparable talk (see Muhinyi et al., Reference Muhinyi, Hesketh, Stewart and Rowland2020 for more detail). Families were visited a year later by the same researcher and children’s language skills were again assessed.

Video-recordings and transcription

Dyads were video-recorded using a small digital camcorder (Samsung VP-MX20/ZEU) placed on a tripod approximately 2 m from the dyad at a 45° angle. The zoom function was used to capture the interaction more closely. Dyads sat in a place where they were comfortable or would normally read together, and were instructed to share the books as they normally would. Televisions were switched off during the video-recording, and the researcher sat away from the dyad.

Video-recordings were transcribed by the researcher in CHAT format (from the CHILDES programs; MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2012). Nonverbal behaviours (e.g., gazing, pointing, page turning) were transcribed where this would aid coding. Utterance boundaries were defined as outlined by Ratner and Brundage (Reference Ratner and Brundage2013) when two or more of the following cues were present: silence for 2 seconds or greater, terminal intonation, or a complete syntactic unit or pragmatically complete contribution (e.g., mother: what’s that?; child: a lizard). Repetitions of the same word (e.g., no no no), rote counting, and character names (e.g., Little Red) were transcribed as single words. For reliability, a second researcher transcribed a separate video until 95% agreement was obtained on utterance boundaries (including utterance type, e.g., question vs. non question). The remaining transcripts were then verified by the second researcher and disagreements were discussed and resolved. Then CHECK and FREQ were then run in CLAN to identify and fix any misspelled words.

Measures

Child Vocabulary

The British Picture Vocabulary Test 2nd edition (BPVS-II; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Dunn, Whetton and Burley1997) was used to measure children’s receptive vocabulary on both visits. Raw scores were calculated and converted to standardized (UK-normed) scores. Administration time was approximately 10–15 minutes.

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status was indexed by postcode using the Education Skills and Training Deprivation deciles of the English Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD, 2015). This scale ranges from 1 to 10 (10 = least deprived). Participants in the present sample lived in areas ranging from the most to the least deprived (see Table 1). This measure was used as it reflects education and income. The majority of participants lived in areas of low deprivation.

Extratextual talk

The total amount of maternal extratextual talk was indexed by the number of word tokens (i.e., the total number of words including repetitions of the same word). Number of word tokens was computed in the CLAN program (Computerized Language ANalysis). The number of utterances was computed as an additional measure of the amount of maternal extratextual talk.

The level of abstraction was coded by coding all maternal extratextual utterances according to the abstraction coding scheme in Appendix 1 (based on work by van Kleeck, Reference van Kleeck, van Kleeck, Stahl and Bauer2003 and widely used in shared-reading research). Utterances not related to the plot (e.g., Do you want to turn the page? Let’s see!) were coded as transactional (van Kleeck, Reference van Kleeck, van Kleeck, Stahl and Bauer2003). If an utterance involved levels of abstraction from more than one category (e.g., an explanation might involve a lower level inference or description), then the highest level was coded. The level of abstraction was indexed by calculating the proportion of abstract utterances (i.e., those involving inference, text-to-life references, prediction, and explanation; see Level 2 and Level 3 in Appendix 1) relative to the total number of extratextual utterances.

The degree of interactivity was indexed by a composite variable comprising the following measures:

Questions. The number of questions was computed in CLAN by identifying all maternal utterances ending in a question mark. Wh-questions. Maternal questions were categorized into wh-questions (i.e., those framed by how, what, which, when, where, who, whose, or why, such as Who is in there? What do you think she’s gonna do? What did they make in the end? Why can’t he see him?). Other questions. All questions that were not wh-questions were coded as other questions. This category included yes/no questions, tag questions, and all other question types (e.g., Are they sweets? It does, doesn’t it? Huh?).

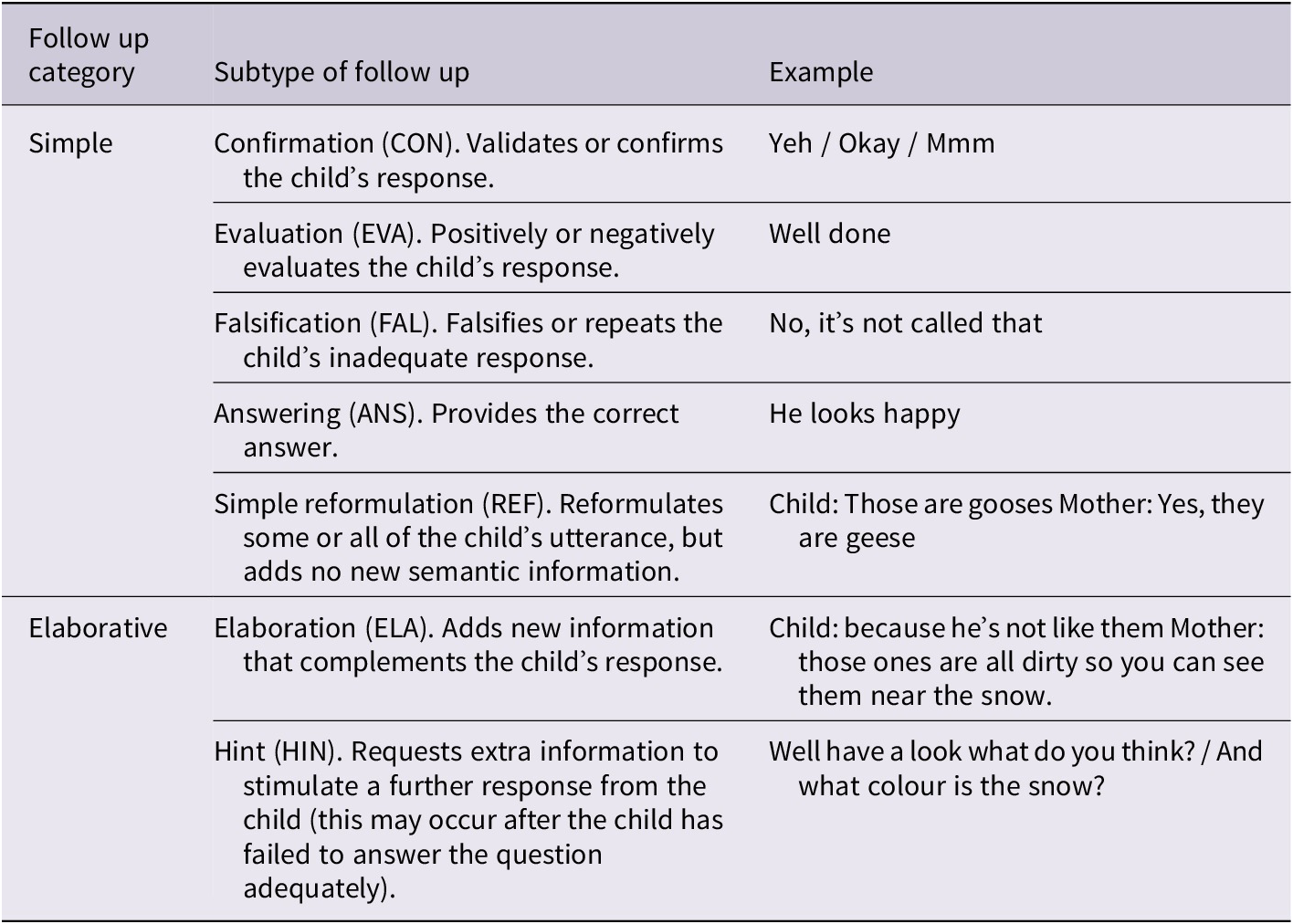

Follow ups. Children’s responses to maternal questions were identified and marked in CLAN. Maternal utterances (both questions and comments) that followed up on the child’s response to a question were then identified in CLAN, and hand-coded as simple or elaborative (based on earlier work by Mascareño et al., Reference Mascareño, Snow, Deunk and Bosker2016; see Appendix 2 for detailed description and examples).

To ensure reliability, 20% of the transcripts were coded by a second coder. Disagreements were discussed and resolved after an initial transcript. Agreement for the level of abstraction and follow ups was 79% and 87.5%, respectively. Kappas (ĸ) were both .76 with corrections made for chance, indicating excellent reliability (Fleiss, Reference Fleiss1981).

Creating the composite variables

We created composite variables to index maternal interactivity and the amount of maternal extratextual talk. Extratextual talk variables were standardized (so that the mean was 0 and standard deviation was 1) and sum averaged. Amount of extratextual talk was a control variable, comprising the number of word tokens and the number of utterances. Interactivity comprised the proportion of all question types and follow ups (both simple and elaborative). Variables comprising the composite variables were positively related among one another, and tended to relate to children’s vocabulary skills in the same direction and in similar magnitude (see Table S1, Supplementary Materials).

Results

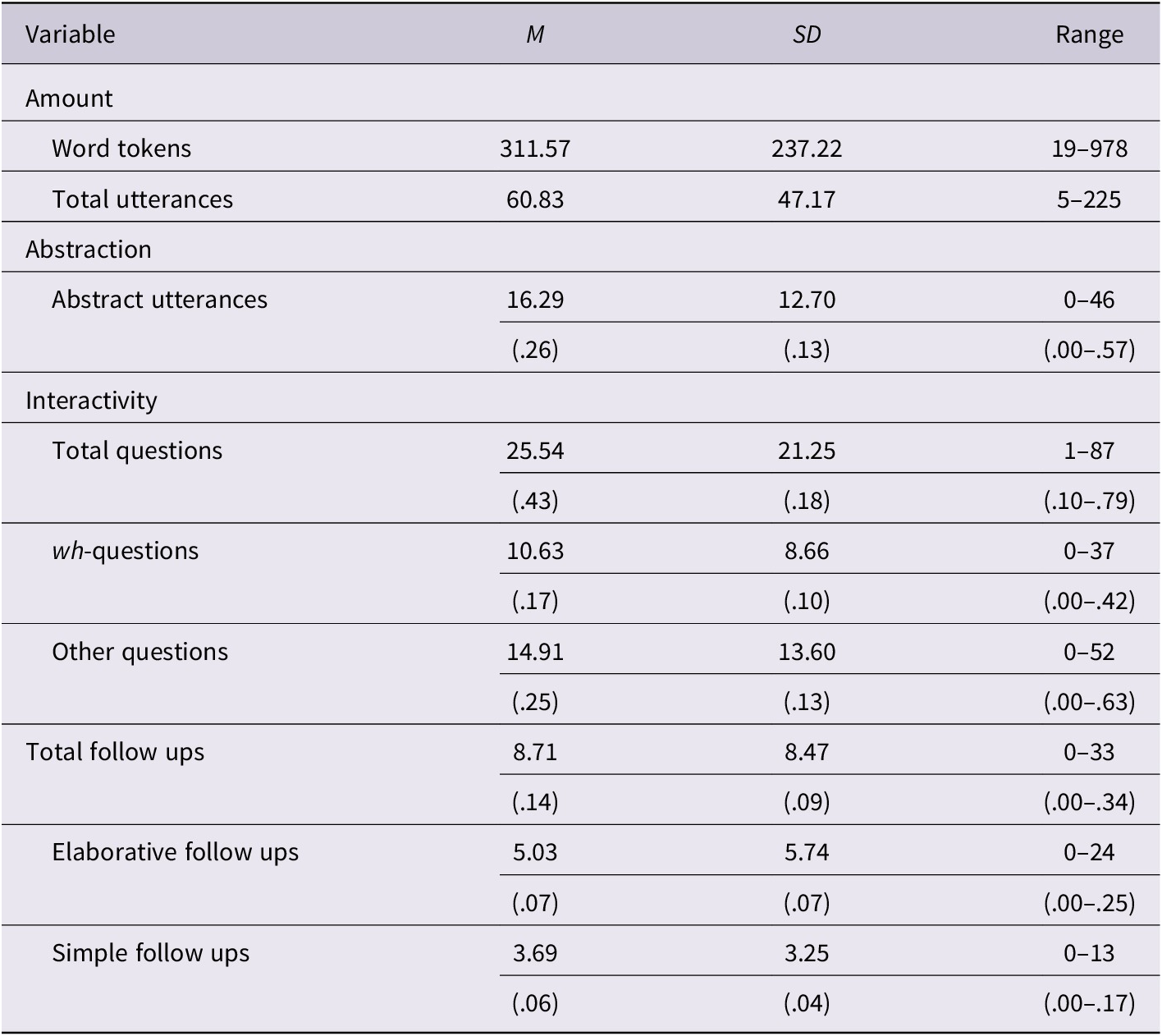

As shown in Table 2, there was considerable variability in maternal extratextual talk. All maternal extratextual talk variables were positively skewed, indicating that most mothers were at the lower end of the ranges shown in Table 2. Proportional measures were used in subsequent analyses, as we were interested in the quality (not quantity) of extratextual talk. Raw vocabulary scores were used, as these reflected greater variability.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for Maternal Extratextual Talk Variables (Proportions)

Note. N = 35. Total follow ups and total questions (frequencies and proportions) may differ from the sum of the components shown in the table because of rounding. Proportions calculated relative to the total number of utterances.

Relations among extratextual talk variables and SES

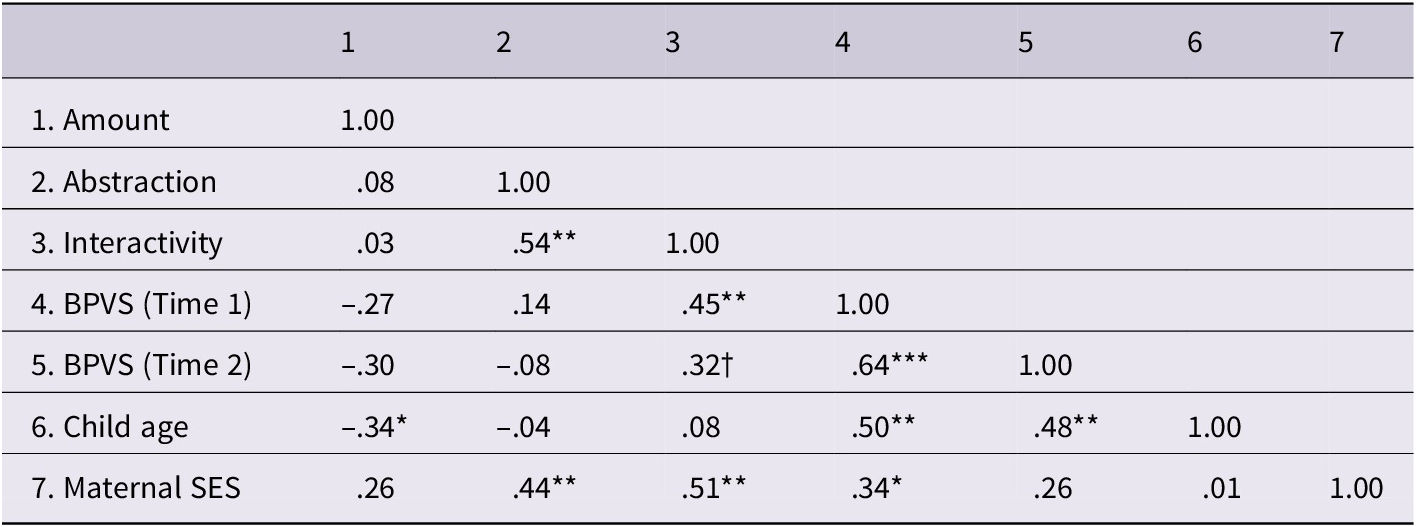

Bivariate correlations among the extratextual talk variables and demographic variables are presented in Table 3. Abstraction was significantly positively correlated with Interactivity (r = .54, p = .001), indicating that on average mothers whose extratextual talk had a higher level of abstraction also used a more interactive style of extratextual talk with their children. Amount was not significantly correlated with Abstraction or Interactivity (rs < .08, ps > .10), suggesting that more verbose mothers did not necessarily use higher quality extratextual talk. Socioeconomic status was significantly positively correlated with Abstraction and Interactivity (r = .44 and r = .51, respectively, ps < .01), and positively but non-significantly correlated with Amount (r = .26, p = .14). Thus on average mothers of higher-SES produced more and higher quality extratextual talk.

Table 3. Correlation Matrix for Composite Extratextual Talk Variables, Child Language Skills, Child Age, and Maternal SES

Note. N = 35. For the correlation between Maternal SES and Amount, n = 34 (one outlying data point was excluded). Pearson correlations were used. BPVS = British Picture Vocabulary Scale. † = p < .10. * = p < .05. ** = p <.01. *** = p < .001.

Assessing multicollinearity

Given the moderate correlations between Abstraction and Interactivity (r = .54, p = .001) and between child age and initial skill (r = .50, p = .002), steps were taken to assess multicollinearity. All Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) were < 10 and tolerances were > .20 (Bowerman & O’Connell, Reference Bowerman and O’Connell1990; Menard, Reference Menard1995; VIFs were in fact < 5, and thus met even more stringent criteria). There were no instances of condition indices above 30 coupled with high variance proportions of >.50 (Tabachnick & Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell2012). Also, the same pattern of results was yielded from separate regressions as in the models presented. Thus we concluded that multicollinearity was not a problem for our analyses.

Predicting children’s concurrent and later language skills

Table 3 shows bivariate correlations between the extratextual talk variables and child skill. Abstraction was not significantly correlated with child vocabulary at either time point (ps > .10). However, Interactivity was significantly positively correlated with children’s initial scores on the BPVS (r = .45, p = .006), and positively, but not significantly, correlated with children’s later scores on the BPVS (r = .32, p = .063).

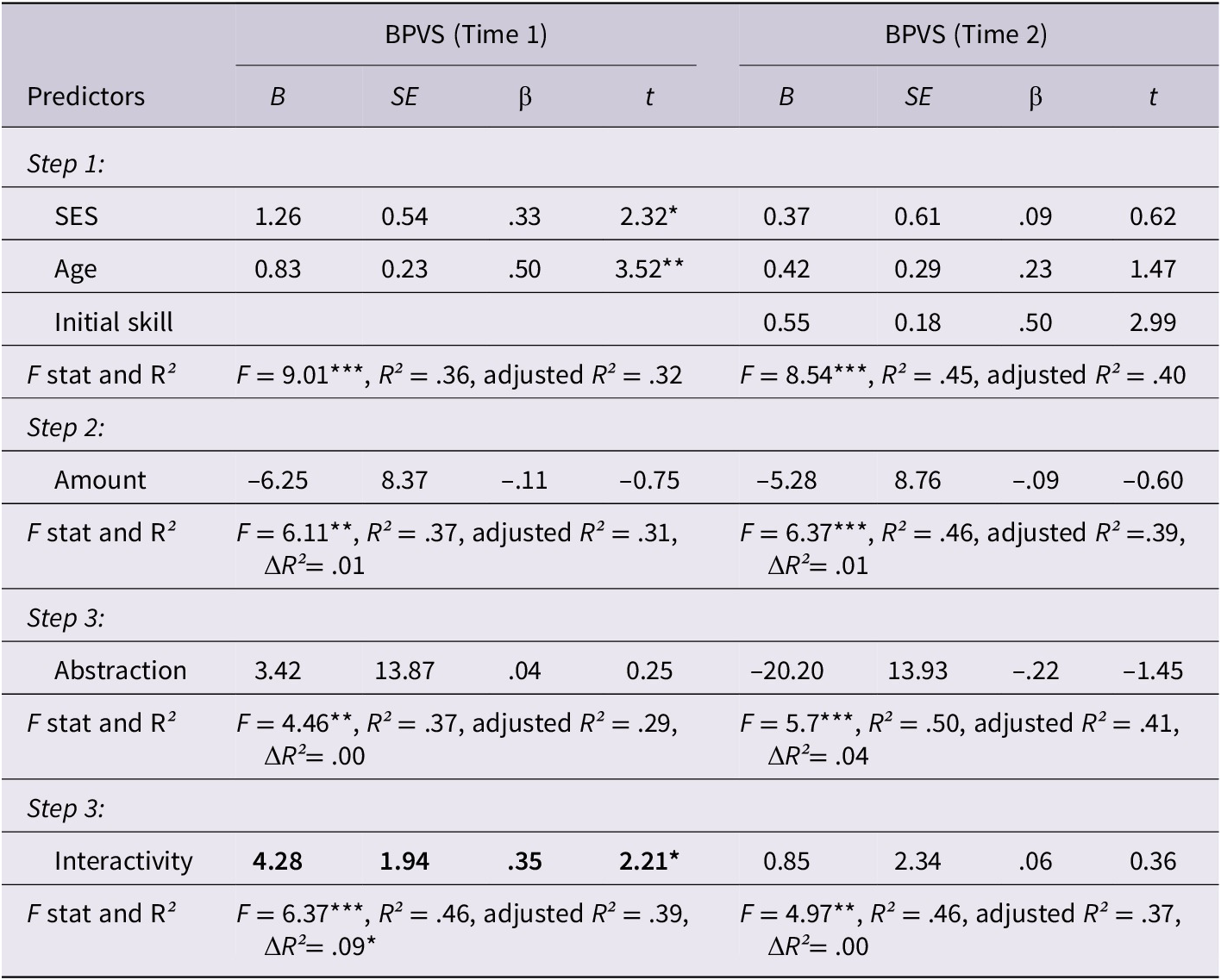

Table 4 shows separate hierarchical regression models for each dependent variable. Step comparisons are based on R-squared improvement. The model predicting concurrent scores on the BPVS indicates that Step 1 (maternal SES and child age) accounted for approximately 36% of the variance in children’s concurrent scores on the BPVS. Step 2 (Amount) did not account for additional significant variance in the model. However, at Step 3, Interactivity was a significant predictor, accounting for an additional 9% of variance in children’s concurrent vocabulary skills, whereas Abstraction did not explain additional variance in children’s concurrent vocabulary skills.

Table 4. Separate Hierarchical Regression Models Predicting Children’s Time 1 (concurrent) and Time 2 (later) Vocabulary Skills With Relevant Controls

Note. N = 35. BPVS = British Picture Vocabulary Scale. SES = Socioeconomic Status. Step 1 (introduction of the control variables) for each dependent variable produced the same results for each of the three Step 2 analyses, thus it is presented only once. Amount was log transformed to correct heteroskedasticity but this did not affect the pattern of results. † = p < .10. * = p < .05. ** = p <.01. *** = p < .001.

The model predicting later BPVS scores indicates that maternal SES, child age, and initial skill accounted for approximately 45% of the variance in children’s later vocabulary skills. Entering Amount at Step 2 did not significantly increase the variance accounted for by the model. Similarly, the extratextual talk variables at Step 3 did not significantly increase the proportion of variance accounted for, and thus neither of these extratextual talk variables were significant predictors of children’s later vocabulary skills. There were no significant interactions among the extratextual talk variables and children’s age or initial skill.

Table 5 shows the overall hierarchical regression models (estimating the simultaneous contribution of abstraction and interactive reading style to variance in children’s language skills). The same pattern of significant results was yielded in the overall regression model as in the separate models, but Abstraction was marginally negatively associated with children’s later skills in the overall model. Note that we also tested for possible two-way interactions of age and initial skill with the extratextual talk variables, and between Abstraction and Interactivity (not presented as none were significant).

Table 5. Overall Hierarchical Regression Models Predicting Children’s Time 1 (concurrent) and Time 2 (later) Vocabulary Skills With Relevant Controls

Note. N = 35. BPVS = British Picture Vocabulary Scale. SES = Socioeconomic Status. Step 1 (introduction of the control variables) for each dependent variable produced the same results for each of the three Step 2 analyses, thus it is presented only once. Step 4 tested for possible two-way interactions of age and initial skill with the extratextual talk variables, and between abstraction and interactivity with the extratextual talk variables (not presented as none were significant). Amount was log transformed to correct heteroskedasticity but this did not affect the pattern of results. † = p < .10. * = p < .05. ** = p <.01. *** = p < .001.

Discussion

We investigated the relation between the level of abstraction and an interactive style during shared reading, and their separate contributions to variance in preschool-age children’s vocabulary skills. Results showed that the level of abstraction was associated with interactivity, and both were associated with SES in our small and largely middle-class sample. Results also showed that high interactivity was associated with children’s concurrent vocabulary skills, but the relation between high interactivity and later vocabulary skills (although positive) was not significant. The level of abstraction was not associated with concurrent or later skills.

Our results suggest that caregiver level of abstraction and use of a highly interactive reading style during shared reading are separate, but related, dimensions of the extratextual talk. Mothers who used a more interactive style also displayed a greater level of abstraction on average (although there was substantial individual variability). This finding supports our prediction that a highly interactive style of extratextual talk, characterized by questions of all types and by follow ups that both appraise and elaborate on children’s responses, provides a context for abstract talk to unfold.

Why did interactivity (versus the level of abstraction) predict children’s concurrent vocabulary development? This finding supports our hypothesis that a highly interactive style during shared reading can support vocabulary learning over and above the sheer level of abstraction because it promotes the child’s active participation and co-construction of meaning (Peterson & McCabe, Reference Peterson and McCabe1994; Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978; Wei, Ronfard, Leyva & Rowe, Reference Wei, Ronfard, Leyva and Rowe2019). It is of course also possible (and likely) that mothers found it easier to engage children with better language skills in elaborations about the book. However, the children in our sample had high language abilities on average, and thus we think that even those at the lower end of the range could participate in highly supported discussions about the story. In addition, the coefficient for interactivity predicting later vocabulary was positive, and we expect that in a larger sample this association might be significant given the magnitude of the effect (t > 1). Thus we tentatively interpret these results as suggesting that in our sample high interactivity supports vocabulary development, rather than simply reflecting it.

Previous research on abstract talk during shared reading has found no strong evidence for one particular utterance function (e.g., abstract questions vs. statements) relating to child vocabulary skill (e.g., Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Bengochea, Nicol and Justice2017; Zucker et al., Reference Zucker, Justice, Piasta and Kaderavek2010). Importantly, our approach reflects the fact that regardless of whether a specific utterance is concrete or abstract, it forms part of an overall style of discourse during shared reading that may be less or more interactive in nature. Collectively, our studies suggest that the overall style of the extratextual talk involving abstract discourse may be important for children’s language development, and that focusing on specific utterance functions at different levels of abstraction or on the level of abstraction alone may miss important processes.

Although our results were generally aligned with our hypotheses, it is unclear why the level of abstraction (and indeed the amount of extratextual talk) did not relate to child skill. This finding conflicts with previous research (e.g., DeTemple, Reference DeTemple, Dickinson and Tabors2001; Hindman et al., Reference Hindman, Connor, Jewkes and Morrison2008; Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Bengochea, Nicol and Justice2017; Zucker et al., Reference Zucker, Cabell, Justice, Pentimonti and Kaderavek2013 – also see Haden, Reese & Fivush, Reference Haden, Reese and Fivush1996 who found that styles characterized by higher level talk and confirmations on children’s contributions predicted children’s later literacy skills). It may be the case that children in our somewhat linguistically advanced sample were just as likely to benefit from mothers simply reading the text as from extratextual talk. However, this interpretation seems inconsistent with the positive association observed between interactivity and child vocabulary skills. The pattern of results observed here suggests that, in our sample at least, children benefitted only from fine-tuned interactions about the book. That is, in the absence of high interactivity (questions and importantly follow ups on child responses), the amount of extratextual talk and its level of abstraction had no bearing on child skills. In line with Rowe and Snow’s recent call (2020), these results warrant further research to clarify the contributions of these separate dimensions of the extratextual talk.

The current findings have some practical implications for shared-reading interventions. Parent training can increase the amount of abstract language used during shared reading (Hockenberger, Goldstein & Sirianni Haas, Reference Hockenberger, Goldstein and Sirianni Haas1999; Morgan & Goldstein, Reference Morgan and Goldstein2004), but there is less evidence of a transfer to children’s language development. Our results suggest that interventions focused on training caregivers to use abstract language in ways that actively support the co-construction of meaning (through questions and follow ups) may be beneficial. Simply increasing the level of abstraction by providing an abstract commentary about aspects of the plot, or asking a greater number of abstract questions that the child may not yet be ready to answer without support, may be less beneficial. Specific training could encourage and support caregivers to ask a variety of questions (including both wh-questions and yes/no questions) when discussing challenging aspects of the plot with preschoolers (Beck & McKeown, Reference Beck and McKeown2001); and to follow up on children’s responses and increase (or indeed lower) the level of abstraction where appropriate (Danis, Bernard & Leproux, Reference Danis, Bernard and Leproux2000). Such training could be especially helpful for families of low SES.

There are several limitations to the present study. Sample size was small, and lack of power may have prevented us from detecting significant associations with later language skills. In addition, multiple models were run, and our sample comprised a fairly wide age range of children (36–59 months); in a larger sample we might have detected significant interactions with age. Future research aimed at teasing apart the contributions of different aspects of the extratextual talk could benefit from a larger, socioeconomically diverse sample, involving less advanced children who are read to less frequently at home. Future research might also benefit from using informational books, which are shown to facilitate more abstract talk than storybooks (e.g., Price, Van Kleeck & Huberty, Reference Price, Van Kleeck and Huberty2009).

In sum, our results suggest that a highly interactive reading style, characterized by questions and follow ups that both appraise and elaborate on children’s responses, provides a supportive context for abstract talk to unfold during shared reading. Encouraging and supporting caregivers to use such a style may increase opportunities for preschoolers to benefit from the abstract talk. Future research that considers both these dimensions of the extratextual talk can further inform our understanding of how shared reading supports young children’s language development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an Economic and Social Research Council studentship awarded to Amber Muhinyi (grant number ES/J500094/1). Caroline Rowland is supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/L008955/1). We thank the participants for their time and willingness to take part, and Leone Buckle and Maxine Winstanley for help with coding and transcription. We also thank Meredith Rowe for providing feedback on an earlier version of this paper. Declarations of interest: none.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000921000696.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Coding Scheme for Level of Abstraction

Note. Coding scheme based on the Coding Categories for Levels of Abstraction (van Kleeck, Reference van Kleeck, van Kleeck, Stahl and Bauer2003). The level of abstraction is indexed by calculating the proportion of abstract utterances (i.e., those utterances at Level 2 and Level 3) relative to the total number of extratextual utterances.

Appendix 2. Coding Scheme for Maternal Follow Ups

Note. Table adapted and modified from Mascareño et al., Reference Mascareño, Snow, Deunk and Bosker2016.