1. Introduction

Political trust, defined as the belief that political institutions do not abuse their power, is a necessary condition for democratic legitimacy. Popular support for a regime is rooted in people's confidence in these institutions, which represents one aspect of diffuse political support essential for the survival of a regime (Easton, Reference Easton1957, Reference Easton1975). By establishing appropriate institutional arrangements, democratic systems emphasize procedural justice to resolve disputes, allocate resources fairly, and prevent corruption. The effective functioning of democratic institutions relies on people's political trust in them. Without such trust, governments face numerous challenges due to a lack of political support (Klingemann, Reference Klingemann and Norris1999; Norris, Reference Norris and Norris1999b). Previous studies argue that the erosion of political trust may not lead to an immediate regime breakdown but does impact people's evaluation of the regime. Over the long run, it also gradually diminishes government efficiency and governance capabilities (Lipset and Schneider, Reference Lipset and Schneider1987; Miller and Listhaug, Reference Miller, Listhaug and Norris1999; Norris, Reference Norris and Norris1999c).

Among the various dimensions of political institutions, public trust in the military remains strong, even in the presence of a democratic deficit. Norris explores the trend of political support since the beginning of the twenty-first century and concludes that the democratic crisis is exaggerated (Norris, Reference Norris2011). However, ‘The gap between the number of countries that registered overall improvements in political rights and civil liberties and those that registered overall declines for 2022 was the narrowest it has ever been through 17 years of global deterioration’ (Gorokhovskaia et al., Reference Gorokhovskaia, Shahbaz and Slipowitz2023: 1). According to global and regional surveys, public confidence in the military is usually higher than in other political institutions, such as the president, congress, and political parties (Malešič and Garb, Reference Malešič, Garb, Caforio and Nuciari2018). Despite the significance of trust in the military, there have been limited studies exploring this topic, both in democratic and non-democratic contexts (Sarigil, Reference Sarigil2015; Garb and Malešič, Reference Garb and Malešič2016; Koehler et al., Reference Koehler, Grewal and Albrecht2022; Solar, Reference Solar2022; Abouzzohour and Yousef, Reference Abouzzohour and Yousef2023).

By examining the trends and factors influencing public confidence in the military, particularly focusing on Taiwan, our study addresses three significant gaps in the existing literature. First, we contribute empirical findings to a topic that has received relatively little attention from scholars. Second, our investigation delves into a unique case study – a developing democracy with considerable economic growth – set within the distinct cultural context of East Asia and its Confucian heritage. Third, we provide data-driven research on a country where state–society relations have rarely undergone empirical scrutiny.

China has long claimed sovereignty over the island, posing a continual threat to Taiwan's democracy (Elleman, Reference Elleman2021). This threat highlights the significance of military trust, both domestically and internationally. Deterring a Chinese invasion and fostering domestic stability are two essential aspects of Taiwan's delicate balance, both of which are promoted by a strong and dependable armed force. However, past issues such as corruption, civil–military tensions, and potential foreign interference can erode that trust. Taiwan must develop a transparent and competent military that safeguards its independence while navigating the challenging geopolitical landscape to boost public confidence in the armed forces and bolster its democracy. In this delicate balance, trust is the cornerstone of security.

Furthermore, this research scrutinizes the important topic of public confidence in the Taiwanese military, highlighting its significance in comprehending the challenges of democratic governance and civil–military relations in East Asia. Trust in the military is fundamental for democratic stability and the maintenance of civilian control over the armed forces. Moreover, the scarcity of study on public trust in the Taiwanese military emphasizes the necessity for additional examination, motivated not only by academic curiosity but also by practical issues. Unlike countries with a history of military rule and varying degrees of democratic control over the military, such as those in Latin America, Taiwan's military has operated within a democratic framework since the early 1990s (Kuehn, Reference Kuehn2008, Reference Kuehn, Caforio and Nuciari2018). Analysing the sources of public trust within this context is crucial because they influence societal support for defence policy and national security initiatives. Stronger public trust can increase deterrence against foreign threats while also facilitating successful mobilization and cooperation with the armed forces during emergencies. Additionally, comprehending the elements that influence public trust in the military is critical for assuring civilian control and encouraging the military's continued professionalization, openness, and accountability. By researching popular faith in Taiwan's military, we acquire unique insights applicable to a democratic country confronting distinct security challenges. This knowledge can help to shape policies targeted at improving national security and building a robust civil–military connection.

Drawing on pertinent works in political science and political sociology that explore public trust in the military and its correlations with political, social, and cultural factors, we formulate a set of hypotheses to elucidate the dynamics of public trust in Taiwan's military between 2001 and 2022. The trajectory of trust in the military in Taiwan aligns with Desch's structural theory, which suggests that the level of trust in the military fluctuates in response to the severity of external threats (Desch, Reference Desch1998). In general, confidence in the armed forces remains higher than that in other political institutions, similar to patterns observed in other countries.

The second goal of this study is to explore the determinants of trust in the military in Taiwan. The statistical evidence indicates strong support for both cultural and institutional explanations of political trust in Taiwan. Among institutional factors, variables such as government trust show a strong correlation with public trust in the military. Moreover, the influence of democratic satisfaction and corruption control, while slightly less pronounced, still plays a significant role in shaping confidence in the armed forces. On the other hand, cultural factors, represented by civic engagement, interpersonal trust, and Confucian hierarchism, also exert noteworthy impacts on military trust, although their influence might not be as potent as the preceding three factors.

The paper's structure will be as follows: first, we will commence with a literature review aimed at comprehending the theoretical significance of public trust in the military and its potential origins within cultural and institutional theories. Derived from these conceivable explanations, we will formulate our primary hypotheses. Subsequently, we will detail the research design, encompassing data collection methods and the measurement of the pivotal concepts outlined in our hypotheses. Additionally, we will discuss the findings concerning the pattern of confidence in the armed forces and delve into its possible determinants. Lastly, we will draw conclusions and propose avenues for future research.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Civil–military relations

The research traditions of civil–military relations have a rich history. The relationships between society and the military are complex and encompass various areas, but at their core lies the question of civilian control (Rukavishnikov and Pugh, Reference Rukavishnikov, Pugh, Caforio and Nuciari2018). The main challenge is the dilemma: ‘how to reconcile a military strong enough to do anything the civilians ask them to do with a military subordinate enough to do only what civilians authorize them to do’ (Feaver, Reference Feaver1996: 149). This paradox stems from the tensions between two forces: a functional imperative and a societal imperative (Huntington, Reference Huntington1957: 2–3). In other words, ‘The very institution created to protect the polity is given sufficient power to become a threat to the polity’ (Feaver, Reference Feaver1999: 214).

There are two main approaches to achieving civilian control over the military in modern democracies: the political science approach and the sociological approach. The former emphasizes creating robust democratic institutions and fostering military professionalism to ensure the military's accountability to society (Huntington, Reference Huntington1957). The latter, championed by Janowitz (Reference Janowitz1960), posits that genuine civilian control requires deeply integrating the military into the broader fabric of society. While some may criticize the conceptual limitations of these approaches (Feaver, Reference Feaver1999), public trust in the military plays a decisive role in facilitating democratic control. For example, greater public faith in the military, coupled with increased professional autonomy but unwavering commitment to societal subordination, can foster a reciprocal relationship that leads to more stable civilian control (Feaver, Reference Feaver2023). Furthermore, higher levels of trust can strengthen the bond between civilians and the military, allowing for minimal intervention from each other. This concept of mutual trust resembles Huntington's definition of ‘objective civilian control’ (Huntington, Reference Huntington1957: 83). However, the premise of objective civilian control may be challenged by some in party-polarized political systems, where individuals, particularly those aligned with the opposition party, view military professionalism as a crucial check on executive power (Krebs et al., Reference Krebs, Ralston and Rapport2023). This phenomenon highlights the intricate nature of the civil–military relationship in modern democracies.

This depiction of the civil–military dynamic, placing a spotlight on public trust in the military, underscores a relationship that extends beyond a simple government–military dyad, encompassing a triad involving the populace, the government, and the military. Huntington (Reference Huntington1957: 89) argues that military influence is, in part, contingent upon the public's perceptions of the officer corps and military leaders, as well as the attitudes of societal groups towards the armed forces. Schiff (Reference Schiff2009) introduces the concordance theory of civil–military relations, suggesting that beyond the military and political elites, the citizenry is a pivotal third participant. The theory posits that when harmony prevails among these three entities on principal matters like the officer corps' social composition, political decision-making procedures, recruitment strategies, and military ethos, the likelihood of domestic military intervention diminishes. Emphasizing the significance of nurturing a positive bond between the military and the citizenry becomes paramount, as their mutual respect and understanding play a critical role in upholding democratic values (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Coletta, Feaver, Gheciu and Wohlforth2018; Rapp, Reference Rapp, Beehner, Brooks and Maurer2021).

To describe the concept of public trust in the military, we need to consider two dimensions: relational and domain-specific. This concept can be expressed by the simple formula: A trusts B to do X. The relational aspect refers to the relationship between the public (A) and the military (B), while the domain of action (X) represents where trust is either given or withheld. At the core of trust lies the belief that A considers B to be trustworthy, expecting them to behave with integrity and competence, and prioritizing A's interests (Citrin and Stoker, Reference Citrin and Stoker2018). Public confidence in the military, defined as the collective belief within a society, reflects the public's evaluation of the performance of its armed forces. These evaluative standards stem from two main sources: cultural perceptions and actual performance. Cultural standards establish the benchmark for how the entire society views the military organization, while performance standards assess whether the military is competent, reliable, and benevolent in fulfilling its mission. When the public deems the military trustworthy and perceives that the military prioritizes the public's interests, it reinforces the legitimacy of civilian control.

2.2 The sources of political trust

There are two distinct theoretical traditions contending to explain the origins of trust: one revolves around cultural factors, while the other centres on institutional factors (Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Hsiao and Wan2009). Cultural theories propose that political trust has its origins beyond the realm of politics, stemming from ingrained and enduring beliefs about individuals that are deeply rooted in cultural norms and transmitted through socialization during early life. As Mishler and Rose (Reference Mishler and Rose2001: 31) state, ‘From a cultural perspective, institutional trust is an extension of interpersonal trust, learned early in life and, much later, projected onto political institutions, thereby conditioning institutional performance capabilities.’ The cultural theory emphasizes the significance of a civic culture with high levels of political trust and interpersonal trust in ensuring the effectiveness of democratic governance (Almond and Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1963; Putnam, Reference Putnam1993, Reference Putnam2000).

Moreover, according to the cultural theories, political trust plays an indispensable role in ensuring the survival and effective functioning of the regime. Political trust not only promotes the public's acceptance of democratic values and ideals but also enhances the quality of political involvement (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993, Reference Putnam2000; Brehm and Rahn, Reference Brehm and Rahn1997; Braithwaite and Levi, Reference Braithwaite and Levi1998; Norris, Reference Norris1999a; Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2005). Cultural theories postulate that trust between individuals fosters trust in institutions. Interpersonal trust allows for greater cooperation and, according to Inglehart (Reference Inglehart1990, Reference Inglehart1997) and Putnam (Reference Putnam1993), contributes to building public trust in political institutions from the ground up.

The cultural theories argue that the source of political trust is exogenous outside the institutional framework, whereas the institutional theories posit that the generation of political trust is endogenous and depends on institutional performance (Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001). According to the institutional theories, political trust and distrust are individual rational responses to the outcomes of institutional performance, with a particular focus on economic performance (Przeworski et al., Reference Przeworski, Alvarez, Cheibub and Limongi1996; Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001). Political trust can reduce transaction cost and facilitate the functioning of political institutions (North, Reference North1990). The institutional theories argue that political trust in institutions and confidence in government are important for the development and maintenance of social trust (Offe, Reference Offe and Warren1999). Therefore, the institutional theories assert that political trust is the result of the expected utility derived from satisfactory institutional performance (Coleman, Reference Coleman1990; Hetherington, Reference Hetherington1998). Scholars have concluded that while the institutional theories have a significant impact on citizens' regime support in post-communist countries, the cultural theories do not exert the same level of influence, although they remain paramount for democracy as well (Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001; Lühiste, Reference Lühiste2006). A comparable trend indicating that the institutional approach holds greater explanatory power for political trust compared to the cultural approach has also been observed in East Asian nations (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Wan and Hsiao2011; Choi and Woo, Reference Choi and Woo2016).

The preceding cultural and institutional approaches both aim to capture the sources of political trust in the government. Governing bodies fall into two categories: representative institutions (legislative, executive) and professional ones (judiciary, military, police, civil service). While the former operates on democratic principles, the latter blend meritocratic, technocratic, and bureaucratic principles. Therefore, due to their emphasis on expertise and neutrality, professional institutions like the military may be perceived as more impartial compared to representative institutions that are more susceptible to political influence (Inoguchi, Reference Inoguchi, Inoguchi and Tokuda2017; Norris, Reference Norris, Zmerli and van der Meer2017). Consequently, investigating the specific patterns of trust in the military can be done through the lens of both cultural and institutional factors.

In addition, this research proposes to explore the longitudinal pattern of general public trust in the Taiwanese military by examining the roots of trust stemming from widespread societal features. This approach seeks to determine how factors affecting society as a whole influence the baseline level of public confidence in the military. This perspective differs subtly from that provided by Feaver (Reference Feaver2023), who discussed the trend of public trust in the American military since the early 1970s. Feaver focused more on variations of trust levels among key demographic groups and delved deeper into the causes of trust at specific points in time, such as 2019 and 2020. This distinction lies in the broader longitudinal scope of our approach compared to the deeper focus on specific time periods in Feaver's investigation into the causes of trust.

The six primary drivers of public confidence in the military highlighted by Feaver (Reference Feaver2023) can be categorized by their impact duration: long-term factors like patriotism (the lingering effects of a rally derived from being a country at war) and professional ethics (where the military upholds high ethical standards), and short-term causes like performance (public judgement of military operations), party influence, personal contact with the military, and public pressure. Our theoretical framework aligns with these categories. The cultural approach captures sources similar to long-lasting factors, establishing the contextual background for societal attitudes towards the military. The institutional approach focuses on sources akin to shorter-term factors like performance. While this study deliberately focuses on a specific range rather than providing a comprehensive overview of all potential trust origins, its framework still offers valuable insights into the sources of political trust in the military.

2.3 The cultural explanations of political trust

By Easton's original formulation, regime support refers to public attitudes towards the legitimacy of a political system with the multiple levels of political support from the most abstract to the concrete: political community, regime principles, regime norms, regime institutions, and political authorities (Easton, Reference Easton1965, Reference Easton1975; Dalton, Reference Dalton2004). The presence of high levels of political trust and a strong civic culture are two defining characteristics of critical or disaffected citizens. These citizens demonstrate strong support for democratic ideals while simultaneously holding critical views of democratic performance (Norris, Reference Norris and Norris1999c; Dalton, Reference Dalton2004; Torcal and Montero, Reference Torcal, Montero, Torcal and Montero2006). Much of the literature on democratic consolidation places a strong emphasis on the formation and promulgation of democratic attitudes and values (Przeworski et al., Reference Przeworski, Bardhan, Carlos, Pereira, Bruszt, Jip Choi, Comisso, Cui, di Telia, Hankiss, Kolarska-Bobinska, Laitin, Maravall, Migranyan, O'Donnell, Ozbudun, Roemer, Schmitter, Stallings, Stepan, Weffort and Wiatr1995; Linz and Stepan, Reference Linz and Stepan1996).

In explaining the sources of political trust from a comparative perspective, two approaches typically emerge: bottom-up and top-down theories. The former emphasizes the significance of individuals' experiences, while the latter considers the characteristics of a political system as factors influencing political trust. Empirically, understanding the patterns of political trust at the micro-level within a country is challenging due to the ambiguity surrounding how social capital, such as participation in voluntary organizations, affects trust. Previous research has shown that the patterns of political trust are clearer at the country level due to the rainmaker effect (Newton, Reference Newton, Torcal and Montero2006, Reference Newton, Castiglione, Van Deth and Wolleb2008; Roßteutscher, Reference Roßteutscher, Castiglione, Van Deth and Wolleb2008). The rainmaker effect suggests that higher levels of trust within a country lead its citizens to perceive their fellow citizens as more trustworthy (Newton and Norris, Reference Newton, Norris, Pharr and Putnam2000; Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Pharr, Dalton, Pharr and Putnam2000). Despite acknowledging variations in trust levels across countries, the rainmaker effect offers no explanation for this variation. We posit that the effects of bottom-up theories align with institutional theories, while top-down theories resemble cultural theories.

Following the principles of the new institutionalism,Footnote 1 actors behave rationally in accordance with rule-based constraints established by the institutional environment (North, Reference North1990). As Offe (Reference Offe, Torcal and Montero2006: 34) notes, ‘These institutional patterns define the ‘possibility space’ of citizenship and political action. They provide a learning environment which frames the citizens’ points of access to the political process, shapes perceptions, defines incentives, allocates responsibilities, conditions the understanding of what the system is about and what the relevant alternatives are.’ Based on these statements, individuals hold two types of beliefs: the first pertains to their own judgements, while the second concerns their perceptions of the surrounding circumstance. When institutionalism is applied to the case of political trust, Rothstein argues that the presence of universal and impartial political institutions fosters social capital, provided that public policies promote social and economic equality (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2005; Warren, Reference Warren and Uslaner2018).

Social capital theory identifies two interconnected aspects: interpersonal social trust and voluntary activism within social groups. Interpersonal social trust refers to the level of trust and confidence individuals have in others within their social networks or communities. It involves the belief that others will act in a trustworthy manner and fulfil their obligations. On the other hand, voluntary activism and belonging to more social groups refer to the level of active participation and involvement in social organizations, networks, or communities. This dimension reflects the extent to which individuals engage in voluntary activities, join community groups, or participate in civic organizations (Fukuyama, Reference Fukuyama1995; Brehm and Rahn, Reference Brehm and Rahn1997; Newton and Norris, Reference Newton, Norris, Pharr and Putnam2000).

These dimensions of social capital theory are often intertwined. Higher levels of interpersonal social trust can lead individuals to engage in voluntary activism and participate in more social groups. Active participation in social groups, in turn, can enhance interpersonal social trust by fostering social interactions, building relationships, and promoting cooperation among members. Therefore, drawing on cultural theories and the social capital thesis (Uslaner, Reference Uslaner and Warren1999, Reference Uslaner2002), we posit that individuals with higher social capital are more likely to demonstrate greater confidence in political institutions, including the military. Building upon this notion, our first hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1: Individuals who possess elevated levels of social capital, either through voluntary activism or through interpersonal trust, are more likely to extend their trust to the military.

Another significant aspect of Taiwan's political culture is the profound influence of Confucianism. Originating in ancient China, Confucianism has deeply impacted the culture and society of Taiwan (Huang, Reference Huang and Oldstone-Moore2023). The principles espoused by Confucianism, including reverence for authority, emphasis on strong family values, hierarchical relationships, and adherence to traditional norms and customs, have become deeply ingrained in the social fabric of East Asian societies. As a result, traditionalism is pervasive across various aspects of life, ranging from politics, family structures, education, to social interactions (Yao, Reference Yao2000; Shin, Reference Shin2012). These enduring traditional values not only significantly shape the overall development of society but also play an underlying role in shaping the patterns of political and economic behaviour among its people (Inglehart and Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005). The impact of Confucianism's influence on the collective mindset and societal norms cannot be understated, as it guides the interactions and decision-making processes of individuals within the Taiwanese society.

The compatibility of Confucianism's orientation, often termed ‘Asian values’, with the acceptance of authority and its relationship with democracy have been subjects of debate among scholars (Huntington, Reference Huntington1996). As Tu (Reference Tu1996: 25) points out, ‘Strong government with moral authority, a sort of ritualized symbolic powerfully accepted by the overwhelming majority, is acclaimed as a blessing, for it is the responsibility of the ruling minority to translate the general will of the people into reasonable policies on security, health care, economic growth, social welfare, and education.’ However, some researchers argue that the Confucian-based authority relations are not necessarily a significant impediment to democratization in East Asia (Dalton and Ong, Reference Dalton, Ong, Dalton and Shin2006). Shin (Reference Shin, Bell and Li2013) further argues that the doctrines of democracy and Confucianism are not inherently contradictory; rather, it is possible to integrate them, emphasizing a system of political meritocracy within democracy.

Thus, while respect for authority, influenced by Confucian values, may lead Taiwanese citizens to trust the government more (Shi, Reference Shi2001), it does not necessarily hinder democratic progress. Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Individuals who hold a stronger allegiance to hierarchical Confucian values are more inclined to have greater trust in the military.

2.4 The institutional explanations of political trust

The institutional theories view performance as the primary influencer of individual trusting attitudes, shaped by rational calculations during decision-making. This perspective is commonly referred to as a motivational approach since it requires individuals to assess whether placing trust in others benefits themselves (Deutsch, Reference Deutsch1960). Unlike interpersonal relationships, political trust centres on the interaction between citizens and the entity composed of political institutions (van der Meer, Reference van der Meer and Uslaner2018).

According to Newton and Norris (Reference Newton, Norris, Pharr and Putnam2000: 61), ‘Government institutions that perform well are likely to elicit the confidence of citizens; those that perform badly or ineffectively generate feelings of distrust and low confidence.’ The evaluations of regime performance can be ‘exemplified by satisfaction with democratic governance and also general assessments about the workings of democratic processes and practices’ (Norris, Reference Norris, Zmerli and van der Meer2017: 24). Specifically, the assessment of trustworthiness is believed to stem from evaluations of the governing party's historical competence in managing public goods and services, along with the effectiveness of accountability institutions and processes. These evaluations are often monitored using objective indicators, such as levels of corruption, adherence to the rule of law, and the state of democracy (Park, Reference Park, Zmerli and van der Meer2017; Norris, Reference Norris2022).

The relationship between regime performance and confidence in specific institutions, like the military, can be understood as a layered system of political support, ranging from diffuse to specific (Easton, Reference Easton1965; Norris, Reference Norris, Zmerli and van der Meer2017). Diffuse support, a general sense of trust and faith in the broader system, acts as the foundation for specific support, which is trust in individual institutions. This connection is likely strengthened when institutions deliver on expected outcomes, avoid major scandals, and demonstrate effective policy-making. Therefore, citizens who hold favourable views of overall government performance and feel empowered to participate in the political process are expected to exhibit greater trust in specific institutions. Consequently, positive evaluations of the overall regime lay the groundwork for trust in its individual components, including the military.

The initial aspect of performance arguments characterizes political trust as individuals' perceptions of the government, shaped by their evaluation of its performance in comparison to their expectations of how it should function (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington1998, Reference Hetherington2005; Hetherington and Rudolph, Reference Hetherington and Rudolph2015). While economic growth is a primary consideration in this context, as it directly impacts people's well-being, policy performance extends beyond the economy to encompass various other areas of government engagement, including national security, socio-economic welfare, and environmental protection (Roller, Reference Roller2005). A government's ability to effectively address these multifaceted issues is imperative for maintaining political trust. This first aspect represents a comprehensive evaluation of government performance, reflecting how well the government fulfils its responsibilities across various areas.

To further conceptualize the government's performance as a whole, we define it as trust in the national government, considering all three branches of political institutions, including the executives, legislation, and judiciary. When citizens perceive a higher level of government performance, they are more likely to place greater faith in other political institutions, such as the military. To test the validity of this argument, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Individuals who demonstrate trust in the central government are more inclined to place their trust in the military.

The second aspect of performance arguments pertains to general assessments about the workings of democratic processes and practices, which focuses on how a variety of people's voices can be taken into account fairly and effectively in the policy-making process. This involves citizen participation and free and fair political competition within an open and responsive political system that channels these inputs into government policies. Additionally, the rule of law with procedural justice plays a fundamental role in resolving political and social disputes, ensuring order in society, and upholding equality before the law as established by the constitution. The process should also be efficient, minimizing transaction costs and avoiding unnecessary burdens, expenses, or intrusiveness (Diamond and Morlino, Reference Diamond, Morlino, Diamond and Morlino2005; Rothstein and Teorell, Reference Rothstein and Teorell2008).

Related to the evaluation of democratic governance, the concept should be approached from two directions: the positive perspective, assessing whether the system is functioning effectively, and the negative perspective, examining whether the system is free from serious interference (Rothstein and Teorell, Reference Rothstein and Teorell2008; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012; Rose and Peiffer, Reference Rose and Peiffer2019). A properly functioning democratic system processes all requests impartially, upholding the principles of fairness and justice. On the other hand, if the democratic system is tainted by corruption, characterized by bending the rules, clientelism, nepotism, cronyism, patronage, and discrimination, it fails to fulfil its purpose. Hence, it is important to assess the quality of democratic governance from both positive and negative viewpoints. To test the validity of this proposition, our fourth hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 4: Individuals who demonstrate higher faith in democratic governance, either through their satisfaction with democracy or by perceiving lower levels of corruption, are more likely to place their trust in the military.

Generally, cultural explanations of political trust delve into the intricate nature of regime support, addressing attitudes towards political systems across various levels. Citizens with high levels of political trust and a strong civic culture are characterized as critical thinkers, supporting democratic ideals while scrutinizing democratic performance. Two main perspectives emerge: top-down theories, considering system-level factors, and bottom-up theories, emphasizing individual experiences. Social capital theory, encompassing interpersonal trust and voluntary activism, plays a crucial role in shaping political trust, with individuals possessing higher social capital more likely to trust political institutions, including the military. Additionally, Confucianism's influence on Taiwanese political culture is significant, potentially shaping trust in the military through hierarchical values (Shi, Reference Shi2015).

Conversely, institutional explanations view performance as the primary determinant of trusting attitudes, shaped by rational calculations. Citizens' evaluations of regime performance, satisfaction with democratic governance, and perceptions of corruption levels significantly influence their trust in specific institutions, such as the military. Trust in the national government correlates positively with trust in the military, reflecting citizens' inclination to extend trust to other political institutions amid higher government performance. These explanations underscore the complex interplay between regime performance, democratic governance, and trust in political institutions like the military (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Wan and Hsiao2011).

3. Data and measurement

This research tests the aforementioned hypotheses using the Taiwan regional datasets from waves 1 to 6 in the Asian Barometer project. These surveys have been conducted longitudinally in 2001, 2006, 2010, 2014, 2018, and 2022, with the aim of grasping the beliefs and behaviours of Taiwanese citizens towards democracy. The sample sizes of the datasets from each wave range from 1,259 to 1,657.

This study investigates trust in the military using a four-point Likert scale with ordered response categories. The scale ranges from 1 (meaning ‘None at all’) to 4 (meaning ‘A great deal of trust’). For further details on the scale's implementation in the questionnaire, please refer to the Appendix Table A1.

The first set of independent variables centres on cultural explanations, with a specific emphasis on social capital. This construct is gauged through two pivotal dimensions: the richness of social connections and the trustworthiness between individuals. The first dimension is assessed by exploring the diversity of organizations to which individuals belong, providing insights into the extent of their social connections and participation in various social groups. The second dimension evaluates interpersonal trust among strangers, following the framework proposed by Warren (Reference Warren and Warren1999a, Reference Warren and Warren1999b). To measure this facet of social capital, respondents are queried about the trustworthiness of others. This question aids in determining the level of trust individuals place in others, contributing to their overall social capital. By scrutinizing these two dimensions of social capital, we can glean insights into its impact on trust in the military.

The second cultural explanation is grounded in the Asian Values thesis of social hierarchy within Confucianism. This hierarchical concept is operationalized through a set of four questions, previously employed in empirical studies on Confucianism by Fetzer and Soper (Reference Fetzer and Soper2013), and Shi (Reference Shi2001, Reference Shi2015). These four questions, namely, ‘Government leaders are like the head of a family; we should all follow their decisions’, ‘When a mother-in-law and a daughter-in-law come into conflict, even if the mother-in-law is in the wrong, the husband should still persuade his wife to obey his mother’, ‘Even if parents’ demands are unreasonable, children should still do what they ask’, and ‘Being a student, one should not question the authority of their teacher’, are utilized in the last four waves of the study. Furthermore, the fourth question is also employed in the second wave, paired with the question ‘The relationship between the government and the people should be like that between parents and children.’ The third question is also featured in the first wave, coupled with the question ‘If there is a quarrel, we should ask an elder to resolve the dispute.’ All these questions are rated on a four-point ordinal scale.

Given that our analysis focuses on hierarchism in Confucianism, an abstract latent variable measured by four ordinal questions, we aim to transform these instruments into a score reflecting the underlying continuum of this personality trait. There are three primary methods for constructing such a dimension: additive models, factor analysis, and item response models. While additive models assume equal weight for all indicators and may not effectively assess dimensionality, and factor analysis requires continuous indicators, item response theory can be applied to discrete ordinal data without such limitations (Raykov and Marcoulides, Reference Raykov and Marcoulides2011; Warshaw, Reference Warshaw, Atkeson and Alvarez2018). Following Raykov and Marcoulides (Reference Raykov and Marcoulides2018), we utilize the graded response model of item response theory to construct the latent variable of hierarchism for our empirical analysis.

Two evaluative concepts form the foundation of performance explanations: the efficiency of government performance and the effectiveness of the democratic system. While social capital can indeed influence government confidence, as Hetherington (Reference Hetherington1998, Reference Hetherington2005) highlights, assessing government performance remains paramount. This assessment should focus specifically on the national government, encompassing all three executive, legislative, and judicial branches, as argued by Brehm and Rahn (Reference Brehm and Rahn1997) – a more robust measure compared to broader government services. In alignment with the methodological approaches of Cook and Gronke (Reference Cook and Gronke2005), as well as Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Wan and Hsiao2011), we measure government performance by examining political confidence in the national government, encompassing all three branches.

The four-point Likert scale used for the dependent variable (‘None at all’, ‘Not very much’, ‘Quite a lot’, and ‘A great deal’) was replicated for trust in the three political institutions. Applying the graded response model of item response theory, consistent with our hierarchism analysis, provided deeper insights into the underlying continuum of individuals' evaluations of the national government's performance.

Moving on to assess democratic governance's effectiveness, we analyse two key aspects: satisfaction with democracy's functioning and perceived prevalence of corruption. The first dimension is measured by asking respondents about their satisfaction with ‘the way democracy works in Taiwan’, capturing their overall perception of the system's effectiveness. For the second dimension, we focus on perceived prevalence of corruption within the national government, asking respondents how widespread they believe ‘corruption and bribe-taking’ are. This allows us to gauge their perception of the government's effectiveness in combating this critical aspect of effective governance.

Beyond our main variables of interest, personal-related variables are indispensable to control for, accounting for the diverse individual socialization processes shaped by unique life experiences. Scholars highlight the influence of political culture and socio-demographic factors like age, education, and occupation on political trust (Christensen and Lægreid, Reference Christensen and Lægreid2005). Cultural sociologists argue that early childhood socialization shapes our enduring values, beliefs, attitudes, and norms, ultimately influencing our trust in individuals, groups, institutions, and even nations. These early experiences become persistent frameworks for interpreting the world within each society (Rotenberg, Reference Rotenberg2010). To comprehensively represent personal variables, we include age, gender, education, residential location (urban or rural), and political interest. Political interest is measured on a four-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all interested, 4 = Very interested) to account for potential variation in engagement with political matters.Footnote 2

4. Trend of the public trust in the military in Taiwan from 2001 to 2022

To comprehend the evolving patterns of institutional trust in Taiwan during the early twenty-first century, we have examined the levels of trust in various segments of both political and social institutions. These include entities such as the military, president, national government, congress, court, political parties, civil service, police, local government, newspapers, TV, the election commission, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The collected data, as presented in Table 1, illustrate that public confidence in the military held the top position in 2001 and 2006, ranked fourth in 2010 and 2014, and secured the second place in 2018 and 2022 among political institutions. This suggests that the level of trust in the armed forces tends to exceed that in other political institutions. This observed trend aligns with the findings of Inoguchi (Reference Inoguchi, Inoguchi and Tokuda2017), and Malešič and Garb (Reference Malešič, Garb, Caforio and Nuciari2018), indicating a consistent pattern of high trust in the military across diverse countries.

Table 1. Political trust in institutions in Taiwan from 2001 to 2022

The data source is from waves 1 to 6 of the Asian Barometer project.

NA means not available.

An examination of data from Table 1 reveals longitudinal variations in trust levels for the military across different time periods. The percentages show a declining trend in trust from 2001 to 2014, with the most significant drop of approximately 11% occurring between 2006 and 2010. Trust in the military continued to decrease by roughly 3.8% and reached its lowest point in 2014. However, thereafter, trust in the armed forces experienced a recovery, surpassing the 60% mark from 2018 to 2022.

This change in the trust trajectory can be attributed to two explanations. The first explanation is systematic, as it involves tracking the fluctuating levels of trust in the military over time. A state that encounters significant external threats while facing minimal internal threats is expected to exhibit the most stable civil–military relations. In such circumstances, the emergence of a civilian leadership experienced and well-versed in national security affairs is more probable due to the challenging international security environment. Additionally, civilian institutions are likely to demonstrate greater cohesion, primarily influenced by the ‘rally ‘round the flag’ effect triggered by external threats. On the contrary, a state that confronts limited external threats but significant internal threats is expected to encounter the least effective civilian control over the military (Desch, Reference Desch1999: 13–15).

In the context of Taiwan, the perception of the degree of external threat posed by the People's Republic of China (PRC) has undergone changes over time. During the presidential term of Chen Shui-bian, spanning from 2000 to 2008, when the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which supports Taiwan Independence, was in power, the external threat and tensions in the cross-strait relationship were notably elevated. However, this situation saw a reduction between 2008 and 2016, during the presidency of Ma Ying-jeou from the Kuomintang party.

Chen Shui-bian's tenure witnessed a heightened focus on Taiwan's independence, contributing to escalated cross-strait tensions. Conversely, when Ma Ying-jeou and the Kuomintang came to power from 2008 to 2016, they pursued a policy endorsing the One China principle (Ho, Reference Ho, Templeman, Chu and Diamond2020), leading to a de-escalation of adversarial relations between Taiwan and the PRC. This shift in stance towards a less antagonistic approach contributed to a decrease in the perceived external threat. This change in the external threat landscape had a substantial impact on public trust in the military. With the decrease in the perceived threat, trust in the military experienced a notable decline, resulting in a drop of approximately 11% between 2006 and 2010. This decline can be attributed to the diminishing sense of urgency regarding external security concerns during the period of reduced cross-strait tensions.

The return of DPP to power in Taiwan, under the leadership of President Tsai Ing-wen in 2016, led to renewed cross-strait tensions. This shift in political landscape also influenced the public's perception of the external threat posed by PRC. As a result, the public's trust in the armed forces experienced an upswing, reaching levels exceeding 60% in both 2018 and 2022.

The level of tension in cross-strait relations has varied over time, reflecting the ideological stances of different Taiwanese administrations. At one end of the ideological spectrum is the ‘One China, one Taiwan’ stance, which asserts Taiwan's sovereignty as a distinct political entity. In the middle of the spectrum is the ‘two Chinas’ stance, which recognizes the PRC and the Republic of China (ROC) as two separate sovereign states. At the opposite end is the ‘One China’ perspective, which views Taiwan as a part of the PRC. Chen Shui-bian and Tsai Ing-wen's administrations both adopted ‘One China, one Taiwan’ stances, which often led to increased tensions with the PRC. The PRC views Taiwan as a breakaway province and has threatened to use force if the island ever declares independence. Pro-independence governments in Taiwan are seen as a threat to the PRC's territorial integrity, and the PRC has responded with military exercises and diplomatic pressure. Conversely, Ma Ying-jeou's government took a more pro-China stance, which aligned with the PRC's position. This resulted in a decrease in adversarial dynamics (Wu, Reference Wu and Lee2019).

To reinforce the argument regarding the fluctuation in the level of hostility in cross-strait relations during the terms of the mentioned presidents, corresponding public opinion polls in Taiwan also reflect a similar pattern. The Taiwan Mainland Affairs Council, a Taiwanese government agency, has consistently commissioned reputable survey organizations to conduct regular telephone surveys on ‘public views on the current state of cross-strait relations’ since 1998. A specific aspect of the survey gauges ‘the attitude of the Chinese Communist Party towards Taiwan’, prompting respondents to assess the level of hostility of the CCP towards the Taiwanese government and people.Footnote 3

During Chen Shui-bian's presidency, encompassing 23 surveys, an average of 63.7% of respondents perceived the Chinese authorities as unfriendly to the Taiwanese government, with 45.2% considering them unfriendly to the Taiwanese people. Throughout Ma Ying-jeou's presidency, spanning 25 surveys, average percentages were 51.3 and 44.7%, respectively. Up to 2023, Tsai Ing-wen's presidency has seen 21 surveys, with average percentages of 69.6 and 52.5%, respectively. These data illustrate that, during Ma Ying-jeou's presidency, public opinion perceived the Chinese authorities as the least hostile to the Taiwanese government and people.

The loss of diplomatic partners can be interpreted as a consequence of increased tension and pressure exerted by the Chinese authorities. This trend offers circumstantial evidence supporting the argument that the level of hostility between China and Taiwan has varied over time. At the onset of Chen Shui-bian's presidency, Taiwan had 29 diplomatic partners, a number that diminished to 23 by its conclusion. During Ma Ying-jeou's term, there was a more gradual decline, with only one partner lost. In contrast, Tsai Ing-wen's presidency has witnessed the sharpest drop, with 9 partners lost by 2023. The divergence in diplomatic losses suggests that the Chinese authorities perceived Chen Shui-bian and Tsai Ing-wen as facing greater hostility compared to Ma Ying-jeou. Thus, the pattern of diplomatic losses under each president supports the contention that the level of hostility between China and Taiwan has experienced fluctuations over time.

The second explanation concerns the short-term impact on public perception of the military, which can be influenced by unforeseen incidents and military propaganda disseminated through media channels. One notable incident is the tragic death of Hung Chung-chiu on July 4, 2013, which stemmed from improper military detention. This event triggered widespread public protests directed at both the Minister of National Defense and the Legislative Yuan of Taiwan. As a consequence, this incident significantly worsened the already low level of trust in the military. This erosion of public trust further deepened, plummeting from 49% in 2010 to 45% in 2014. However, trust rebounded, surpassing the 60% mark following the DPP's return to power in 2016.

In essence, fluctuations of trust in the military of Taiwan can be primarily attributed to the perceived severity of external threats, particularly from China. This perception has fluctuated in response to changes in Taiwanese administrations and their respective cross-strait policies. Desch (Reference Desch1999) argues that strong civilian control over the military thrives when external threats are high and internal threats are low. In such circumstances, both the public and the military prioritize the maintenance of national security to avoid open conflict. Social identity theory posits that individuals derive self-esteem and identity from their group affiliations (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981). When faced with a severe external threat, both the military and society may avoid internal conflict to maintain a unified national identity, which is pivotal for national cohesion and survival. Furthermore, avoiding internal conflict serves not only to strengthen social cohesion but also as a strategy aimed at ensuring the group's survival and success in overcoming the threat (Cuhadar and Dayton, Reference Cuhadar and Dayton2011).

This structuralist perspective helps explain the changing dynamic between civilian and military authority in Taiwan during this period. During this period without internal threats within Taiwan, the degree of civilian control of the military increases along with the degree of external threats. Simply put, stronger external threats result in stronger democratic control of the military. With stronger democratic control, the public can monitor the military's conduct to ensure it acts in the people's interest to protect the country. Thus, the levels of public faith in the military should also increase along with the degree of democratic control of the military.

5. The empirical results of partial proportional odds models

The scale measuring public confidence in the military consists of four ordinal points: 1 for ‘None at all’, 2 for ‘Not very much’, 3 for ‘Quite a lot’, and 4 for ‘A great deal of trust’. The dependent variable under investigation is categorical, offering four distinct values with a clear hierarchy. This configuration suggests that an ordered logit model is the most suitable choice for this analysis. The regression equation predicting a specific Taiwanese citizen's trust in the military is represented as follows:Footnote 4

However, a potential issue linked to ordered logit models is the assumption of proportional odds, also known as parallel regressions. This assumption posits that the influence of the independent variables on the dependent variable remains consistent across all levels of the dependent variable. Violation of this assumption might introduce bias into the results of the ordered logit model (Long and Freese, Reference Long and Freese2014).

The fundamental characteristic of the data structure in the dependent variable is its ordinal nature with multiple attributes. Reducing it to an indicator variable with only two categories, as done in statistical models like the logit or probit models, risks significant information loss and oversimplification of the inherent complexity in the data. Similarly, maintaining the same degree of regression slopes across all categories may be overly simplistic, as social phenomena often exhibit more intricate patterns than straightforward variations. Conversely, completely abandoning the ordinality and treating the attributes as mere unordered categories could introduce excessive complexity. In this context, utilizing partial proportional odds models to analyse the ordinal dependent variable by relaxing the assumption of parallel regressions on some of the independent variables can be seen as a balanced choice among these statistical models.

In the absence of theoretical reasoning to predict potential asymmetric impacts of explanatory variables on trust levels in the military, we take a data-driven approach to assess the parallel regression assumption. We aim to determine whether there are any violations of the parallel regression assumption among the independent variables. The Brant test, a widely used method, evaluates whether observed differences between predictions from the proportional odds model and actual data exceed what can be attributed solely to random chance (Brant, Reference Brant1990). The Brant test results from the six-wave surveys indicate that some independent variables of interest, as well as certain control variables, do not adhere to the proportional odds assumption.Footnote 5 As a result, we will proceed to analyse the data using a partial proportional odds model. This model will incorporate both the parallel regression assumption for most variables and relax the same assumption for some variables.

The partial proportional odds model operates by comparing category 1 against categories 2, 3, and 4. The second panel then contrasts categories 1 and 2 with categories 3 and 4, while the third panel compares categories 1, 2, and 3 with category 4. In simpler terms, the j th panel yields outcomes equivalent to those of a logistic regression where categories 1 through j are recoded to 0 and categories j + 1 through M are recoded to 1. Simultaneously estimating all equations leads to slightly differing results compared to the separate estimation of each equation. When interpreting outcomes for each panel, keep in mind that the current category of Y and the lower-coded categories serve as the reference group (Williams, Reference Williams2006, Reference Williams2016).

The results of the empirical analysis using partial proportional odds regressions are presented in Tables 2–7. The right-hand side of the regression models is divided into two sections: research and control variables. Since hypotheses 1 through 4 propose theoretical relationships between the dependent variable and the independent variables, and these hypotheses are directional in nature, one-tailed hypothesis testing will be employed in the subsequent discussion.

Table 2. Trust in the military: partial proportional odds models – Taiwan 2001

N/A, not at all; NVM, not very much; QALOT, quite a lot of trust; AGD, a great deal of trust.

Only one set of coefficients is presented for explanatory variables that meet the proportional odds assumption.

The data source is the wave 1 of Asian Barometer project. The number of cases is 881. Standard errors are in the parenthesis. The tests of research variables are one-tailed, and the rest of the tests are two-tailed, denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

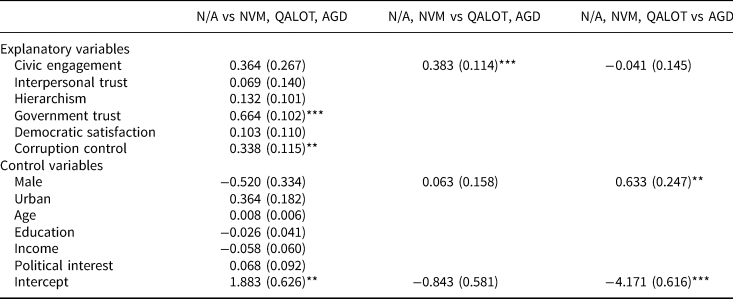

Table 3. Trust in the military: partial proportional odds models – Taiwan 2006

N/A, not at all; NVM, not very much; QALOT, quite a lot of trust; AGD, a great deal of trust.

Only one set of coefficients is presented for explanatory variables that meet the proportional odds assumption.

The data source is the wave 2 of Asian Barometer project. The number of cases is 1103. Standard errors are in the parenthesis. The tests of research variables are one-tailed, and the rest of the tests are two-tailed, denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Table 4. Trust in the military: partial proportional odds models – Taiwan 2010

N/A, not at all; NVM, not very much; QALOT, quite a lot of trust; AGD, a great deal of trust.

Only one set of coefficients is presented for explanatory variables that meet the proportional odds assumption.

The data source is the wave 3 of Asian Barometer project. The number of cases is 1210. Standard errors are in the parenthesis. The tests of research variables are one-tailed, and the rest of the tests are two-tailed, denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Table 5. Trust in the military: partial proportional odds models – Taiwan 2014

N/A, not at all; NVM, not very much; QALOT, quite a lot of trust; AGD, a great deal of trust.

Only one set of coefficients is presented for explanatory variables that meet the proportional odds assumption.

The data source is the wave 4 of Asian Barometer project. The number of cases is 1298. Standard errors are in the parenthesis. The tests of research variables are one-tailed, and the rest of the tests are two-tailed, denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Table 6. Trust in the military: partial proportional odds models – Taiwan 2018

N/A, not at all; NVM, not very much; QALOT, quite a lot of trust; AGD, a great deal of trust.

Only one set of coefficients is presented for explanatory variables that meet the proportional odds assumption.

The data source is the wave 5 of Asian Barometer project. The number of cases is 904. Standard errors are in the parenthesis. The tests of research variables are one-tailed, and the rest of the tests are two-tailed, denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

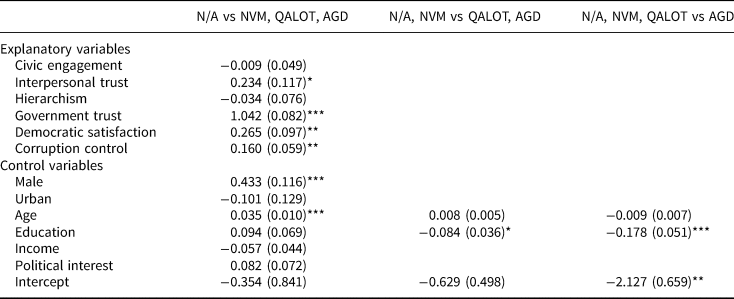

Table 7. Trust in the military: partial proportional odds model – Taiwan 2022

N/A, not at all; NVM, not very much; QALOT, quite a lot of trust; AGD, a great deal of trust.

Only one set of coefficients is presented for explanatory variables that meet the proportional odds assumption.

The data source is the wave 6 of Asian Barometer project. The number of cases is 1286. Standard errors are in the parenthesis. The tests of research variables are one-tailed, and the rest of the tests are two-tailed, denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Hypothesis 1 suggests a positive relationship between social capital and trust in the military. During the first two decades of the twenty-first century, Taiwanese individuals who engaged in a greater number of organizations or groups and had more connections within civil society tended to exhibit higher levels of trust in the military. Similarly, individuals who perceived others as more trustworthy were also more inclined to trust the military.

The first hypothesis is supported by statistical evidence in the results presented in Tables 2–4, 6, and 7, with the exception of Table 5. The concept of social capital consistently demonstrates its ability to enhance trust in the military, whether through individuals' active engagement in various social groups or their willingness to cooperate with others within society. Specifically, the variable ‘civic engagement’, which signifies social density and is measured by the number of social groups in which respondents participate, exhibits statistical significance in round 1 (2001) and round 3 (2010). Additionally, the variable representing trust in strangers is statistically significant in round 2 (2006), round 5 (2018), and round 6 (2022). To validate hypothesis 1, a test of the joint significance of the coefficients for the two variables in each round (the χ2 test of the Wald statistic) yields P-values of 0.014 in round 1, 0.052 in round 2, 0.002 in round 3, 0.957 in round 4, 0.006 in round 5, and 0.253 in round 6. Hence, we can conclude that hypothesis 1 is supported in four out of the six surveyed rounds.

Hypothesis 2 postulates a connection between the traditional values of hierarchism in Confucianism and an increased level of societal trust in the military. In Taiwan, as a Confucian society, citizens who have been socialized to embrace or inherit traditional values are more inclined to internalize these principles. They perceive a strong government with moral authority as favourable, viewing government actions not as intrusive but as benevolent (Tu, Reference Tu1996). Consequently, they are also more likely to extend this trust to the military. This hypothesis finds backing in the outcomes reported in Tables 3–6. In these tables, the coefficient estimates for the hierarchism variable exhibit a consistent positive direction and statistical significance, with P-values lower than 0.05. Nevertheless, the hypothesis is not substantiated by the results presented in Tables 2 and 7, where the coefficient estimates for the hierarchism variable do not attain statistical significance. On the whole, hypothesis 2 garners support in four out of the six rounds that were surveyed.

Hypothesis 3 suggests that a higher level of trust in the government corresponds to a stronger sense of confidence in the military. After considering the influence of cultural factors, Taiwanese citizens tend to view government performance as indicative of the military's credibility in fulfilling its duties. If citizens perceive that the government acts in the best interests of the people, they are likely to deem it trustworthy. Then, the military, as an integral part of the government's political machinery, is also likely to gain greater public trust. This hypothesis is strongly supported by the statistical findings across all tables. The coefficient estimates for the ‘trust in the national government’ variable consistently show a positive direction and are statistically significant with P-values below 0.05. These findings underscore the significant influence of Taiwanese citizens' perceptions of government performance, as measured by their trust in the government, on their attitudes towards the military.

Hypothesis 4 posits that the higher evaluations of the democratic system correlate with greater trust in the military. Government performance is not the sole criterion for trust evaluation; the democratic process, which involves impartially considering diverse voices from various segments of society, is equally important. This fair political process fosters a balanced government that reconciles competing policy objectives and generates compromises accepted, albeit not entirely satisfactorily, by society. It is through such democratic processes that a stable and efficient government can be maintained. Thus, Taiwanese citizens who perceive the political process as bound by law and free from improper interference caused by cronyism and money would have higher political support for the functioning of the political system as a whole. In turn, these Taiwanese individuals, with more faith in the entire democratic system, would also place greater trust in the military, which is a specific component of the political institutions.

The assessment of democratic governance is gauged through two variables: democratic satisfaction and corruption control. The coefficient estimates for the first variable, democratic satisfaction, consistently demonstrate a positive and statistically significant relationship in Tables 3–5 and 7. Similarly, the coefficient estimates for the second variable, corruption control, also exhibit a positive and statistically significant association in Tables 2, 4, 5, and 7. These robust statistical outcomes lend substantial support to hypothesis 4. Furthermore, to validate this hypothesis, we conducted a χ2 test of the Wald statistic for the joint significance of the coefficients for both variables in each round. The results of this statistical test yield P-values of 0.006 in round 1, 0.002 in round 2, 0.001 in round 3, 0.000 in round 4, 0.229 in round 5, and 0.002 in round 6. This confirms that hypothesis 4 is substantiated in five out of the six surveyed rounds.

Analysis of the statistical evidence underscores substantial support for hypotheses 1 and 2, rooted in cultural explanations of political trust, in Taiwan over the first two decades of the twenty-first century. Similarly, hypotheses 3 and 4, derived from institutional explanations of political trust, receive significant empirical backing. An evaluation of the consistency across all survey rounds, taken as a reliable criterion to assess the efficacy of these two types of political trust explanations, reveals the institutional explanation to be more robust than the cultural one. The statistical results of the institutional explanations consistently hold true across all six survey rounds.

To solidify our claim, we combine data from six survey rounds into a single dataset encompassing the years 2001–2022. We employ a consistent model specification across all six rounds on this pooled data, and the results are presented in Table 8. The consistent pattern across these outcomes underscores the greater robustness of the institutional explanation relative to the cultural one. Institutional factors exhibit statistically stronger significance throughout the pooled dataset compared to cultural factors. This finding aligns with prior research findings to a certain extent (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Hsiao and Wan2009, Reference Wong, Wan and Hsiao2011; Choi and Woo, Reference Choi and Woo2016).

Table 8. Trust in the military in Taiwan: partial proportional odds models (2001, 2006, 2010, 2014, 2018, and 2022)

N/A, not at all; NVM, not very much; QALOT, quite a lot of trust; AGD, a great deal of trust.

Only one set of coefficients is presented for explanatory variables that meet the proportional odds assumption.

The data source is the 6 waves of Asian Barometer project. The number of cases is 6682. Standard errors are in the parenthesis. The tests of research variables are one-tailed, and the rest of the tests are two-tailed, denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

6. Conclusion and discussion

This study endeavours to unveil the dominant trend of public trust in the Taiwanese military spanning from 2001 to 2022, alongside exploring the underlying factors that shape it. The trajectory of trust in Taiwan's military corresponds to Desch's structural theory, positing that military adherence to civilian mandates hinges on the interplay of external and internal threats confronting a nation. Trust levels in the military exhibit fluctuations in reaction to the gravity of external threats. Notably, the general trend showcases that confidence in the armed forces surpasses that in other political institutions, mirroring patterns discernible in other global contexts.

The second objective of this research is to delve into the determinants underlying the levels of trust in the Taiwanese military. The statistical findings strongly endorse both cultural and institutional interpretations of political trust within Taiwan. In terms of institutional factors, variables such as trust in the government are closely associated with public confidence in the military. Additionally, the effects of democratic contentment and control over corruption, while somewhat less pronounced, still wield a significant sway over the formation of trust in the armed forces. Conversely, cultural aspects, as exemplified by civic participation, interpersonal trust, and Confucian hierarchism, also contribute noteworthy influences on military trust, although their impact might not be as robust as the four aforementioned factors.

While the study centres on Taiwan, broadening its scope through a comparative analysis with other nations sharing similar structural factors – particularly the contrast between a smaller, less powerful armed forces country and a larger, powerful one – would provide a more comprehensive understanding. This approach could unveil commonalities or distinctive trends in political dynamics, yielding valuable insights into potential generalizability. Drawing parallels to Taiwan's situation concerning China, the comparison between Ukraine and Russia, or more broadly, any former Soviet state and Russia itself, serves as a pertinent example. In such scenarios, trust in the military within the smaller country assumes a vital role in deterring or responding to potential threats of infringement from the larger one.

This research represents a preliminary exploration, opening avenues for future investigation. Several potential directions for further research are worth considering. First, broadening the scope to include other East Asian nations would facilitate a comparative analysis between Taiwan and its regional counterparts. Such an approach could unveil common influences on trust in the military, including geographic factors, Confucianism, and patterns of international interaction and trade dependencies.

Second, delving deeper into the Taiwan case could uncover additional factors that strongly impact trust in the military. Conducting more extensive analyses may reveal overlooked variables or dynamics contributing significantly to observed trust levels.

Finally, exploring trust in the military as an independent variable and its influence on Taiwanese citizens' attitudes towards other political issues, such as Taiwan independence, national identity, or party identification, could yield valuable insights into broader socio-political dynamics. This holistic approach would enhance our comprehension of the intricate relationships between trust in the military and various socio-political dimensions.

In summary, expanding the country scope and conducting further investigations within the Taiwan context will lead to a more nuanced understanding of trust in the military and its implications in East Asia.

Supplementary material

The link for the replication data is: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/MBLV59

Appendix

Table A1. Variables, measurement, and descriptive statistics