Introduction

Populist parties have for long failed to enter public office, but as of the late 1980s they began to be elected to political administrations. In Italy, populist parties have continuously been in parliament, either in government or in opposition, at least since the reshuffle of the Italian party system in the mid-1990s, making Italy a case of special interest in exploring the behaviour of populist parties in office. Against this background, it seems counterproductive that the literature on populism has remained disconnected from the study of policy agendas. Yet, due to recent events that have brought populist parties to office in various countries, there have been some attempts to fill this gap.

The behaviour of political parties in office has in fact been extensively studied by the scholars focusing on agenda-setting and issue competition in Europe and the United States (see Borghetto and Carammia, Reference Borghetto and Carammia2010). These studies, however, have mainly considered the traditional party families that have ruled European polities over the past decades, and only occasionally looked at the behaviour of populist parties (for an exception, see Borghetto, Reference Borghetto2018). Specialists of populism, too, have paid little attention to how populist parties shape government agendas, and have predominantly focused on radical-right parties, explaining coalition formation choices (De Lange, Reference De Lange2012, but see Otjes and Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2021), and their consequences on some specific policy areas, notably immigration (Albertazzi and McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015; Bobba and McDonnell, Reference Bobba and McDonnell2016; Kaltwasser and Taggart, Reference Kaltwasser and Taggart2016). As a result, we still know little about differences between the behaviour of populist and non-populist parties in office as we lack an empirical account of these divergences.

The present paper is another effort to bridge this gap, exploring to what extent do populist and non-populist parties behave differently when they are in office? And to what extent is their behaviour shaped by them being in government and in opposition? We follow an issue-attention approach (e.g. Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005; Green-Pedersen and Mortensen, Reference Green-Pedersen and Mortensen2010) and consider issue emphasis in policy agenda as the key strategic choice driving the behaviour of political parties in government and in opposition.Footnote 1 This approach assumes that political parties in office behave strategically, that their strategies are mainly driven by issue attention choices, and that therefore parties will choose to emphasize the issues on which they expect to obtain electoral benefits.

Our analysis covers populist and other parties in Italy over more than two decades (1996–2019), identified using The PopuList (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019). We use unique data from the parliamentary questions to capture parties' strategies in government and in opposition (discussed below). Data were originally collected by the Italian team of the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP) (Borghetto and Carammia, Reference Borghetto and Carammia2010; Russo and Cavalieri, Reference Russo and Cavalieri2016) and updated by the authors. Our unit of analysis is each parliamentary question, coded following the Italian Agendas Codebook, which adapts the CAPFootnote 2 master codebook (see Bevan Reference Bevan, Baumgartner, Breunig and Grossman2019) to Italy. To measure attention distribution in parliamentary agendas and compare populist and other parties we rely on a classic measure in the policy agendas literature: entropy (John and Jennings, Reference John and Jennings2010; Alexandrova et al., Reference Alexandrova, Carammia and Timmermans2012). We find mixed results depending on whether populist parties are in government or in opposition. Indeed, when in government populist parties behave just like other parties, most likely because populists have extra incentives to portray themselves as ‘competent’ policymakers. In contrast, when in opposition populist parties adopt a more concentrated agenda, arguably to signal their difference from other ‘elite’ parties.

The paper proceeds as follows. We begin by discussing available knowledge on the behaviour of (populist) parties in office and speculate on the conditions under which populist parties are likely to behave differently to other parties. Second, we describe the design and methods used in the paper. Specifically, we present the Italian context and clarify the use we make of the disputed notion of ‘populism’ in the present research. In addition, we provide details on the technique of content analysis used to code parliamentary questions and compare populist and other parties, which enables establishing whether and to what extent they behave differently. Finally, we present our exploratory results, before discussing their implications for the scholarly understanding of party government and the so-called ‘normalization’ of populism in contemporary democracies.

Theoretical framework and expectations: understanding the behaviour of populist parties in office

The behaviour of populist parties in office, and notably their influence on the agendas of parliaments has been explored by previous studies on agenda setting, political parties and populism. Yet, most of the studies on the general mechanisms of policy agenda formation have neglected the specificity of populist political actors, whereas the few studies that have looked at populist parties have done so without comparing them to more established political actors. In other words, the scholars of agenda setting and those of populism have by and large talked past each other. As a result, we still lack an empirical account of standing differences between the behaviour of populist and non-populist parties in office.

Scholars of agenda setting and issue competition have provided useful insights on how political parties behave in government (Greene, Reference Greene2015). These studies have mainly addressed parties belonging to the traditional party families that dominated European polities over the last century (Mair, Reference Mair2013). Building on classical accounts of party competition, salience theory and issue-ownership theory (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996), scholars contend that governing parties behave strategically, choosing to stress those issues on which they have an advantage over their competitors (see Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Budge, Reference Budge2015). For a long time, the classic left-right ideological divide has structured issue competition strategies and informed party mandates (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Mair, Reference Mair2013). Scholars have demonstrated that until the 1980s the implementation of welfare state policies was more likely when left-wing majorities were in office (see Imbeau et al., Reference Imbeau, Pétry and Lamari2001), since right-wing ones would opt for spending on domestic security and public order (Klingemann et al., Reference Klingemann, Volkens, Budge, Bara and McDonald2006; Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2012). Further analyses have shown that the left-right ideological divide has started to lose momentum (Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave and Zicha2013), mainly because parties try to fulfil their mandate by matching their electoral pledges to swings in citizens' preferences (Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995) and media attention (Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave, Baumgartner, Bevan, Breunig, Brouard, Chaqués Bonafont, Grossman, Jennings, Mortensen, Palau, Sciarini and Tresch2016).

Other accounts have posited that issue attention is crucial to understand the behaviour of parties in office and the formation of policy agendas (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005; Adler and Wilkerson, Reference Adler and Wilkerson2013; Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2019). These researchers have elaborated an ‘attention-based model of party mandate’, which sees issue attention as a particular type of information that parties want to signal to their voters, as they struggle to control the content of the policy agenda (Froio et al., Reference Froio, Bevan and Jennings2017). Acting as an information processor, parties adapt their policy agenda to take into account the flow of information coming from the external environment and public concerns. In this interpretation, issue attention is not only about the affirmation of political parties' preferences before elections: rather, it constitutes a more complex and dynamic process by which parties continuously adapt their agendas, behaving as ‘agenda setters’ or as ‘agenda takers’ when overwhelming problems drive citizens' priorities (Borghetto and Russo, Reference Borghetto and Russo2018).Footnote 3

Specialists of issue competition and agenda setting have predominantly focused on the behaviour of traditional party families: that is, conservative and social democratic parties that have alternated in government throughout the 20th century. The arrival of populist parties in office is a relatively recent development in European politics (Albertazzi and McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015), and the study of their policy impact is still limited. Specialists of political parties and populism have looked at populist actors primarily from the vantage point of electoral competition, since they are considered responsible for the reconfiguration of political conflict in contemporary democracies (see Bale et al., Reference Bale, Van Kessel and Taggart2011; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Mudde and Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2012; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). The study of contemporary populism has mainly focused on the radical right, given the growing relevance that these parties acquired in political competition (see Mudde, Reference Mudde2019), and investigated mostly the content of their electoral campaigns, their strategies of coalition formation (De Lange, Reference De Lange2012; Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019) and, more recently, their policy impact (Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2001). In this respect, extant literature recognizes that populist parties have potentially direct influence over policy outputs when they enter government (Schain, Reference Schain2006; Akkermann, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2012), but the extent to which they have succeeded in influencing policies is still debated.

Researchers have emphasized that populist parties tend to behave weakly when they are in office, mainly due to organizational difficulties in transitioning from opposition to government in terms of lack of qualified personnel and expertise outside their ‘owned’ issues, notably immigration (Heinisch, Reference Heinisch2003; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007: 266, 281). Others indicate that populist parties can successfully shape public policy when they redirect policy action towards their issues of predilection, mostly immigration and European integration (Zaslove, Reference Zaslove2004; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2014; Albertazzi and McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015). While knowledge on the behaviour of populist parties in office is not scarce (see for an overview Albertazzi and McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015; Louwerse and Otjes, Reference Louwerse and Otjes2019; Otjes and Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2021), only a few studies have compared the behaviour of populist parties in government to that of other parties, and even fewer have paid attention to policy issues other than immigration (Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2001; Schain, Reference Schain2006; Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2012; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2014).

To fill this gap, the paper compares the behaviour of populist and other parties systematically, looking at differences and similarities in issue-attention profiles when they are in government as opposed to when they are in opposition. In this framework, issue attention in policy agendas provides information on the strategic behaviour of populist parties in office. Building on extant research on political parties and issue competition, our overarching expectation is that the behaviour of populist parties in office differs depending on their institutional role. Specifically, we expect that in government the behaviour of populist parties will not differ much from other political parties, as they will be subject to the same institutional constraints as well as to demonstrating their ‘responsible’ government credentials. Conversely, when in opposition, we anticipate that populist parties display different behaviour compared to other parties, exhibiting a more concentrated agenda, seeking to signal their difference from mainstream competitors.

Previous studies have suggested that parties in government are compelled to broaden their agendas as they must cope with a wide range of issues linked to state governance responsibilities (Greene, Reference Greene2015), including economic affairs, defence, and international relations (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Bevan, Timmermans, Breeman, Brouard, Chaqués-Bonafont, Green-Pedersen, John, Mortensen and Palau2011; Alexandrova et al., Reference Alexandrova, Carammia and Timmermans2012), as well as policy legacies and other commitments (Adler and Wilkerson, Reference Adler and Wilkerson2013). These constraints are likely to be particularly compelling for populist parties, as often they have limited credentials as governing parties. Many citizens still regard populist parties as too inexperienced, incompetent, or radical to perform a government's daily operations (Steenbergen and Siczek, Reference Steenbergen and Siczek2017: 123). By diversifying their policy agendas, populist parties in government behave similarly to non-populist ones and might therefore signal to their voters that they can cope with government responsibilities and handle everyday policymaking.

Conversely, populist parties are likely to display concentrated agendas when they are in opposition because this is the role in which they can take greatest advantage of their ‘challenger’ profile. Previous studies have suggested that some populist parties are ‘single-issue’ – in that they concentrate on a few issues closely associated with their campaigns and reputation (see Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2001; Mény and Surel, Reference Mény and Surel2002) – or ‘niche’ – in that during electoral campaigns they focus on issues transcending the traditional Rokkanian cleavages (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). Today, however, most populist parties are no longer at the fringes of their political systems, and several have also broadened their electoral agendas (Bergman and Flatt, Reference Bergman and Flatt2020) and entered public administrations. Yet, they still present themselves as an alternative to, or as challengers of, the economic and political ‘establishment’ (Mudde and Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2012). Our expectation thus rests on the idea that, when populists are in opposition, they are free to follow an issue selection strategy signalling their voters that they differ from other parties and from the ‘elites’. In other words, by concentrating on a few issues at the core of their campaigns they refrain from compromising on issues that other parties have placed on public agendas and maximize the expected returns of being ‘challengers’.

To sum up, we anticipate that populist and non-populist parties behave similarly in terms of issue attention when in government but not in opposition. Specifically, we expect populist parties to have a more concentrated and focused agenda than other parties when in opposition, but to have less freedom when in government. As populism remains a much-debated concept, the next section elaborates on the specificities of the Italian case, discusses how we define populist parties and introduces the data and methods of the study.

Research design

Italy: populist parties in government and in opposition for over two decades

Like other representative democracies, in the 1990s, Italy experienced the emergence of populist parties and their access to parliament. Since then, these parties have continuously sat in parliament, held government and/or opposition roles for over two decades, and have turned Italy into the ‘promised land of populism’ (Tarchi, Reference Tarchi2015b). In this context, identifying populist parties is challenging and it calls for some conceptual and empirical clarifications.

Populism remains a highly contested concept and scholars continue to disagree on whether it constitutes an ideology (Taggart, Reference Taggart2000; Mudde and Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2012) or a style (Laclau, Reference Laclau2005; Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2016; Müller, Reference Müller2016). Nowadays however, researchers agree that populism refers to a set of ideas about the antagonistic relationship between the ‘corrupt’ elites and the ‘virtuous’ people with the inherent arguments that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people (Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019). The paper follows this minimalist definition to identify populist and non-populist parties and to study their behaviour in parliament. This choice implies recognizing that extremism (i.e. the opposition to the democratic constitutional order) is not a constitutive component of populism per se (for a discussion, see Mudde and Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2012; Eatwell, Reference Eatwell, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017). While populism may be combined with some form of radicalism, in that populists oppose specific tenets of liberal democracy, we consider it incompatible with political extremism as populists do not fully reject democracy as a system of government. This approach is based on that of The PopuList (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019), which we use to classify Italian parties (see below).

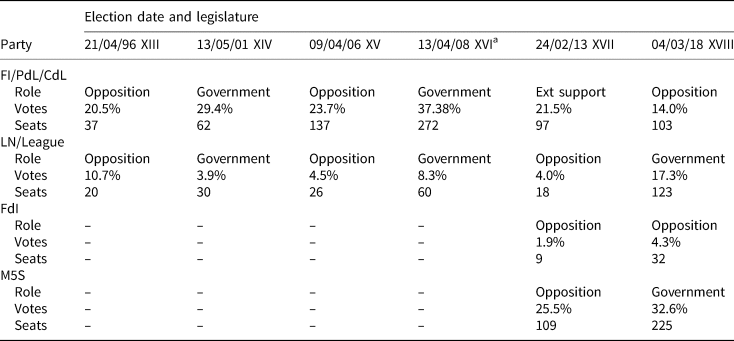

While populism in Italy is not a recent phenomenon (for an overview see Tarchi, Reference Tarchi2015a), its contemporary outbreak traces its roots to the mid-1990s, with the implosion of the Italian political system, a major crisis which radically transformed Italian politics up to the present day. The Tangentopoli corruption scandal emerged in 1992 and led to the demise of long-standing Italian parties: the Christian Democratic Party (Democrazia Cristiana) which governed Italy in different coalitions uninterruptedly between 1946 and 1994, the Italian Socialist Party (Partito Socialista Italiano) and the Italian Communist Party (Partito Comunista Italiano). This crisis culminated in the so-called ‘Second Republic’, a political system characterized by the emergence of (re)new(ed) populist parties, with different ideological leanings that took part in government and/or opposition repeatedly for over 20 years (Verbeek and Zaslove, Reference Verbeek and Zaslove2016) as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Populist parties in Italy: electoral results and role in parliament

Source: Archivio storico delle elezioni, Dipartimento per gli affari interni e territoriali, Ministero dell'Interno (https://elezionistorico.interno.gov.it). Note: General election results and number of seats refer to the lower chamber. Populist parties identification based on The PopuList (2019), available at: https://popu-list.org/.

a After the appointment of the Monti cabinet in November 2011, only the League (among the parties in the table) did not accorded external support to the new government.

Not all populist parties enjoyed the same electoral support. Among the most successful, Berlusconi's personal parties (Forza Italia, then La Casa delle Libertà and Il Popolo delle Libertà and then Forza Italia again) dominated the Italian party system, holding both government and opposition roles for over two decades, endorsing a pro-market liberal anti-left platform to appeal to ‘hard working, upstanding’ people (Raniolo, Reference Raniolo2006; Ruzza and Fella, Reference Ruzza and Fella2011). In addition to Silvio Berlusconi's parties, other electorally successful populist parties in Italy have been those on the radical right and notably the League (Lega) and Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d'Italia), characterized by strong nativist and Eurosceptic agendas (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi2003; Albertazzi et al., Reference Albertazzi, Giovannini and Seddone2018). Another successful populist party emerged recently, in late 2009: the Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle, M5S) funded by Beppe Grillo, a comedian and subsequently activist and blogger (Mosca, Reference Mosca2020). The M5S failed to fit into the traditional categories of left and right (Pirro, Reference Pirro2018; Mosca and Tronconi, Reference Mosca and Tronconi2019), configuring a specific form of ‘techno-populism’ that combines technocratic appeals to expertise and populist invocations of the people (Bickerton and Invernizzi Accetti, Reference Bickerton and Invernizzi Accetti2018). In the 2018 general elections, the M5S tried to distance itself from radical-right positions on immigration in an attempt to find a coalition agreement with the mainstream left Democratic Party (Partito Democratico, PD). Yet, after the refusal of the PD to form a joint government, the M5S agreed to form the first all-populist coalition government in Europe with the League. That government lasted 1 year after which the PD agreed to form a new coalition with the M5S.

In sum, the fragility of the First Republic paved the ground for the emergence of contemporary populist parties in Italy after the mid-1990s. Although enjoying different electoral support, these parties have held both government and opposition roles for around 30 years, making Italy's ‘Second Republic’ a special case for the study of populist parties' behaviour in office.

Data and methodology

To compare the behaviour of populist and other parties in office, our analysis looks at the content of the Italian parliamentary question time – the weekly oral questions posed by MPs in the lower chamber – over the past six legislatures, from the initiation of the ‘Second Republic’ (1996–June 2019). Parliaments are crucial venues for the formulation of policy agendas, as they constitute the formal institution where parties compete to fulfil their representative role in between elections (Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave and Zicha2013). In Italy, question time (interrogazioni a risposta immediata) was tested in 1996 and then officially introduced in 1997 (Art. 135-bis Camera dei Deputati). Parliamentary questions are just one of the many possible parliamentary activities, and questions do not necessarily translate into policy outputs (Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2010), but they are a core intermediate step in the policymaking process between elections (Soroka, Reference Soroka2002; Otjes and Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2018). In fact, parliamentary questions serve the ‘symbolic’ purpose of signalling preferences, where parties try to gain an advantage over their competitors by strategically choosing which issues to emphasise (Russo and Wiberg, Reference Russo and Wiberg2010; Wagner and Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014), thus providing an appropriate measure of party behaviour inside parliaments (Russo, Reference Russo2011; Vliegenthart and Walgrave, Reference Vliegenthart and Walgrave2011; Russo and Cavalieri, Reference Russo and Cavalieri2016; Borghetto and Russo, Reference Borghetto and Russo2018). In other words, oral parliamentary questions expand and update the conflict over issues that are priorities at a given time. For these reasons, the paper considers parliamentary questions as an appropriate institutional venue to investigate parties' strategic behaviour in office, whether in government or in opposition.

Our unit of analysis is each parliamentary question, coded according to the CAP codebook for Italy, which distinguishes among 21 macro topics (see Table A1 in the Appendix). We use The PopuList Footnote 4 (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019) to identify populist and other parties in Italy (see Table A2 in the Appendix). To assess and compare issue attention and the size of the agenda of populist parties with other parties when they entered the Italian parliament, we use an indicator of agenda entropy, derived from information theory (Shannon, Reference Shannon1948). Measuring the entropy means looking at the attention dispersion across policy issues. This varies from complete concentration, when a single issue dominates the entire agenda, to complete diversity, when all items receive an equal level of attention. Scholars of agenda setting and public policy have applied this measure extensively (e.g. John and Jennings, Reference John and Jennings2010; Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Bevan, Timmermans, Breeman, Brouard, Chaqués-Bonafont, Green-Pedersen, John, Mortensen and Palau2011; Alexandrova et al., Reference Alexandrova, Carammia and Timmermans2012). Also known as Shannon's Information Entropy Index or Shannon's H,Footnote 5 the normalized entropy score ranges from 0 or low entropy (when attention is concentrated on one single topic) to 1 or high entropy (when the attention is spread evenly across more topics). To compute the normalized version of the Shannon Diversity Index (H), we applied the classic formula suggested by Boydstun et al. (Reference Boydstun, Bevan and Thomas2014):

In the formula, xi is a policy topic and p(xi) is the proportion of total attention to that specific topic; ln(xi) is the natural log of the proportion of attention to that topic; n is the total number of topics.Footnote 6 For the analyses, we calculated the entropy index for each party.

Results

In this section, we compare issue attention in the policy agendas of populist and non-populist parties as it appears during the question time. The empirical investigation is structured following the general expectation of this study: hence, we first look at similarities and differences between populist and non-populist parties in general, and then explore if these patterns can be explained by parties' institutional roles.

We begin by assessing whether populist and non-populist parties behave differently during question time. For this, we calculate the entropy scores for populist and non-populist parties and compare them. If populist parties behave differently to other parties, we should find that in the parliamentary questions the policy agenda of populist parties is concentrated on a smaller number of issues than the agenda of other parties. Subsequently, we calculate the share of attention that populist and non-populist parties attribute to each issue item in the parliamentary questions. This allows us to see if the size of the agenda of populist parties is linked to their emphasis on specific issues.

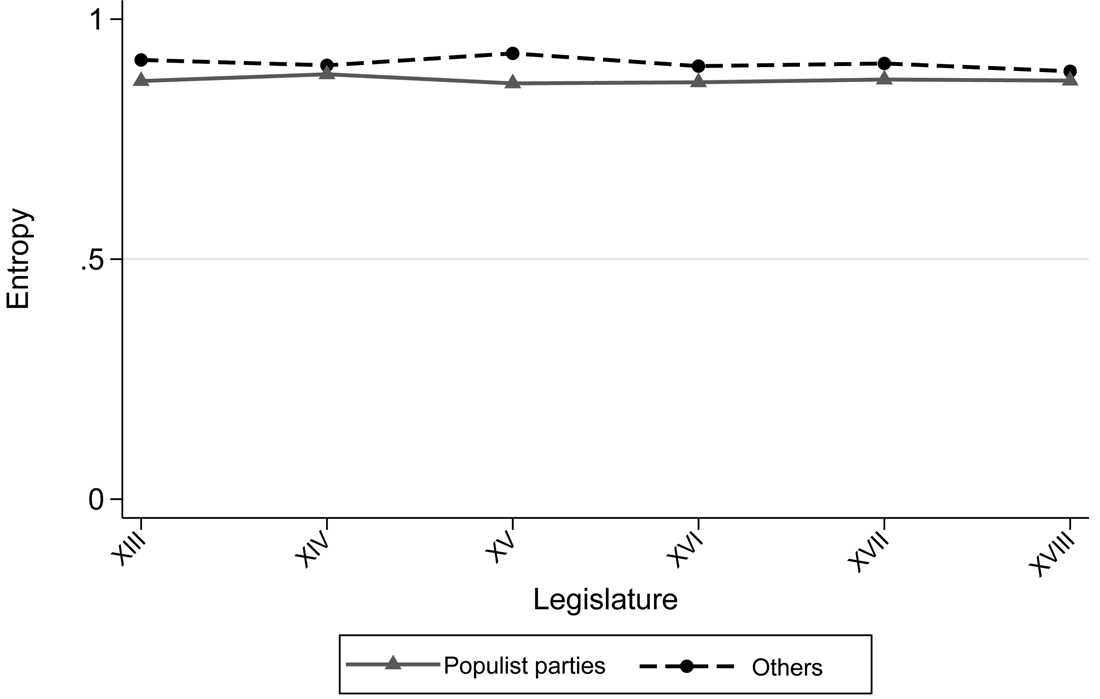

Figure 1 shows entropy scores for populist (triangle) and other parties (circle) across legislatures.

Figure 1. Entropy across legislatures.

Note: Entropy score is 0 when attention is concentrated on one single topic, and 1 when the attention is spread evenly across more topics.

The results illustrate that the entropy scores for both populist and non-populist parties are relatively high (>0.8), but those of non-populist parties remain higher (>0.9) than those of populist parties (>0.8) across legislatures. These findings suggest that, in the parliamentary questions, populist parties have a higher tendency than non-populists to concentrate on a few issues, signalling different behaviours. To see whether this is associated with emphasis on specific issues by populist parties, Figure 2 illustrates the share of attention that populist and non-populist parties attribute to each issue in the question time. The graph shows the 10 most frequent topics (out of 21; counts on all topics are reported in Table A1 in the Appendix) addressed in the parliamentary questions by populists and other political parties.

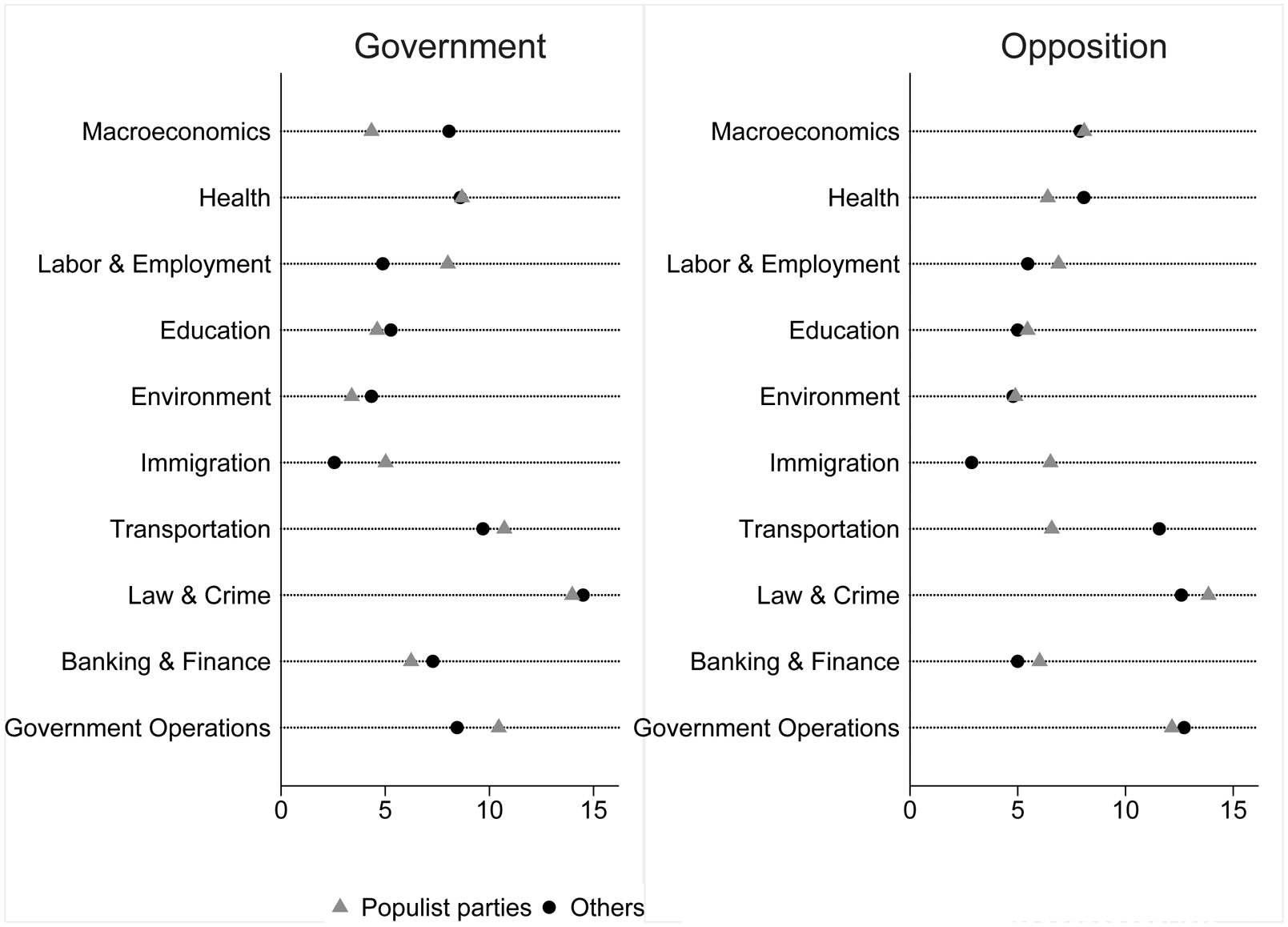

Figure 2. Issue attention by populist and non-populist parties in government and opposition.

Figure 2 indicates that there are important issue attention differences between populist parties and other parties. Populist parties tend to focus more than other parties on ‘Immigration’ as well as on ‘Labour and Employment’. In particular, more than 5% of all the parliamentary questions by populist parties focus on ‘Immigration’, whereas less than 3% of those of other parties have the same focus. This also occurs with questions related to ‘Labour and Employment’, which count for 7% of the agendas of populist parties and less than 5% in the agenda of other political parties. Less sizable differences exist for ‘Law and Crime’ and ‘Government Operations’, which populist parties emphasize slightly more than other parties in the question time. For ‘Law and Crime’ and ‘Government Operations’ attention from non-populists is also relatively high, although it is still lower than for populists. In addition, the theme on which there seems to be an issue emphasis mechanism is ‘Immigration’ which scores high in the agenda of populists and low in the agenda of non-populists (+ 6% of attention by populist parties). To test for the significance of our results, we run t-test statistics. These confirm that the difference in the attention profile of populist and non-populist parties is statistically different from 0 (t = 2.26, d.f. = 5962, P < 0.1). These findings mirror those of previous studies suggesting that populist parties choose different strategies to compete with non-populists (Albertazzi et al., Reference Albertazzi, Bonansinga, Vampa, Albertazzi and Vampa2020). In particular, populist parties tend to concentrate on a narrower set of issues than other political parties, to differentiate themselves from their competitors. Among these, ‘Immigration’ is an issue over which some populist parties (radical right ones) enjoy an advantage as ‘issue owners’.

We now turn to the second step of our investigation, to understand if these differences depend on the institutional role of populist parties in office. If this is the case, then we should find: (a) that the distribution of attention between populist and non-populist parties is not different if we account for their role in government; and (b) that the difference in attention distribution by populist and non-populist parties in opposition is higher than the same difference when they are in government. As before, to examine these patterns, we calculate entropy scores and distributions of attention for populist and non-populist parties when they are in government and when they are in opposition, and we compare between them. The results suggest that the entropy score of non-populist parties in government is higher than that of populist parties in government, albeit the difference is minimal (0.81 for populist parties and 0.82 for non-populists). Moreover, in opposition the entropy score of non-populist actors is higher than that of populist parties (respectively 0.85 and 0.80). In other words, the difference between incumbents and challengers is more pronounced for populist than for non-populist parties – thus their strategy of issue attention is more subject to change depending on their role (government/opposition) within institutions. To zoom on these trends, we calculated entropy scores for the (Northern) League in the XVII legislature (opposition) and the XVIII legislature (government). We found that the entropy score of the League in government (0.88) is slightly higher than when the party is in opposition (0.86), confirming that when populists are in government, they expand their agenda to address a broader set of issues.

Substantively, these findings are in line with what scholars have called the ‘normalization’ of the previously ‘fringe’ role of populist parties (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019), as they learn the formats of parliamentary behaviour. Nevertheless, these findings also highlight that populists experience the difference between being in government and being in opposition more than other parties. To examine whether this is also linked to specific issue emphasis by populist parties, Figure 3 explores the share of attention to each issue by populist and non-populist parties in government and the same for populist and non-populist parties in opposition.

Figure 3. Issue attention by populist and non-populist parties.

In line with our previous findings, the graph on the left in Figure 3 shows that in government there are some issue attention differences between populist parties and other parties on ‘Labour and Employment’, ‘Immigration’, and ‘Government Operations’. Interestingly enough, the issue over which differences between populist and other parties in government are smaller is ‘Law and Crime’, despite the importance it plays in the Italian electoral campaigns (Castelli Gattinara, Reference Castelli Gattinara2016). However, the t-test statistics show that the difference in the attention profile of populist and non-populist parties in government is not statistically different from 0 (t = −0.90, d.f. = 5962, P > 0.1), suggesting that the attention profile of populist and non-populist parties in government is not statistically different. This is in line with our expectation about the impact of the ‘constraints’ mechanism on the behaviour of populist parties in office. Moving to the behaviour of populist parties in opposition, the graph on the right in Figure 3 compares attention distribution between populist and non-populist parties in opposition. We find that there are some important issue attention differences, especially on ‘Immigration’, ‘Labour and Employment’ and ‘Law and Crime’, to which populist parties devote systematically more attention than other parties during question time. The difference is larger for ‘Immigration’, to which populist parties in opposition dedicate more than 6% of all parliamentary questions, whereas other parties less than 3%. The t-test for the attention profile of opposition parties displays significant results (t = −1.81, d.f. = 5101, P < 0.1), suggesting that the distribution of attention of populist parties in opposition is statistically different from that of non-populist parties in opposition and confirming our expectation about the ‘challenger’ mechanism.

To sum up, we find that populist parties concentrate on a few issues and overemphasize specific issues when they are in opposition while, when they are in government, they distribute attention across a broader set of topics and differences with other parties are not significant. Substantively, these findings suggest that populist and non-populist parties behave differently when they are in opposition but not when they are in government. In the conclusions we discuss these findings and speculate on their implications.

Discussion and conclusions

This study bridges research on agenda-setting, political parties and populism to explore the behaviour of populist parties in office. It has offered a preliminary attempt to unravel the influence of populist parties in government and in opposition using analytical tools borrowed from the literature on agenda setting. Specifically, we followed an issue attention approach and traced issue concentration in the parliamentary questions in Italy over the period 1996–2019. With respect to previous attempts to study populist parties in office, this paper takes an innovative approach as it compares populist political parties to other parties and it considers their institutional role (in government and/or opposition) that may condition parties' behaviour. We can draw two main conclusions from this study. First, we find that differences between populist and other parties in terms of issue emphasis exist and they are statistically significant, suggesting that populist parties maintain their focus on key issues of strength. Specifically, we showed that populist parties tend to concentrate on a narrower set of issues than other political parties, to differentiate themselves from other more mainstream competitors. Second, we find that the behaviour of populist parties in office changes depending on their institutional role. In fact, when in government, differences between the entropy scores of populist and other parties are relatively small and not statistically significant. Conversely, differences between the entropy scores of populist parties and other parties in opposition are larger and statistically significant. In other words, when populists access office, they do not behave differently from other parties when in government (signalling that they are ‘competent’ policymakers), but their behaviour when in opposition is different (signalling that they are different from ‘elite’ ones).

Although exploratory, these results allow us to identify some specific features in the behaviour of populist parties in office and how they adapt to the rules of parliamentary institutions. Populist parties have a higher tendency than others to concentrate on a few issues, not just because they are ‘ideologically’ populist nor simply because they run for elections as ‘challengers’. Instead, it is the combination of being populist and the institutional role that is fundamental in differentiating the attention profile of political parties. In government, populist parties expand their agendas, an issue attention strategy that allows them to play the role of ‘competent’ and ‘responsible’ political parties able to handle everyday policymaking and its constraints. In opposition, instead, they play the ‘challenger’ card of single-issue entrepreneurs in a much more pronounced way than other political parties. Our findings are in line with those by Louwerse and Otjes (Reference Louwerse and Otjes2019). While using a different research design and data, they show that the main driver of populist parties' parliamentary behaviour in opposition is not to ‘propose amendments to change policies’ (Louwerse and Otjes, Reference Louwerse and Otjes2019: 481) but rather to ‘scrutinise government action’ (ibid.).

Further research on policy agendas and populist parties could focus on other cases to understand whether populists with different ideological leanings (notably radical-left or radical-right) in other countries and institutional venues (especially those of executive bodies) provide similar results. In addition, future research should also look at the influence of coalition-formation mechanisms on issue attention and policy agendas when populist parties are in office. Similarly, our analyses did not consider the general policy priorities of voters during electoral campaigns. It might well be that populist parties attempt to align policy agendas with past electoral promises, pressing issues of the day or with the ‘party system agenda’ (Green-Pedersen and Mortensen, Reference Green-Pedersen and Mortensen2010), as suggested for other parties. Future studies focusing on electoral campaigns, rather than parliamentary questions, could scrutinize the relationship between ‘nicheness’ and populism during elections, to understand if and how being a niche party mediates populism and issue concentration in policy agendas.

This paper is only a first, although fundamental, step to understand how populist parties in office use their power, by combining insights from the literature on agenda setting, political parties and populism. This is crucial because it contributes to understanding how populist parties adapt to the rules of parliamentary institutions, deflating the myth of populists' exceptionalism, at least in terms of their behaviour in parliament. As discussed by Mudde (Reference Mudde2016), so far the political ‘illegitimacy’ of populist parties seems to justify a kind of exceptionalism in the way these parties have been studied. In fact, for a long time scholars have dealt with populist parties using theories intended to explain their specificities, treating them as ‘outsiders’. Yet, many of these parties have now existed for decades, have survived their founder leaders and have either joined coalition governments with mainstream parties (see Fidesz, Freedom Party of Austria, M5S, etc.) or (more rarely) formed populist governments (see the League and M5S; Syriza and the Independent Greeks – National Patriotic Alliance). These developments suggest that it is time to study populist parties with the theories used to study established political parties, not just as ‘challenger’ parties. For these reasons, we believe that while these results are exploratory and drawn from the Italian context, they hold broader implications for the study of political parties, public policy and the so-called ‘normalization’ of populism in contemporary democracies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2021.25

Funding

This research was funded by the Università degli Studi di Roma Unitelma Sapienza, under grant name ‘Se il populismo diventa maggioranza: cittadini e classe politica in Italia’ led by Prof. Nicolò Conti.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments throughout the publication process. We are also grateful to the Italian team of the CAP for sharing the data. We also want to express our gratitude to Pietro Castelli Gattinara and those who provided valuable input at the 2019 ECPR panel ‘Politics in Polarised Southern Europe’.