Article contents

The Word Order in Saravi Dialect and Spoken Persian Language: A Typological Comparative Study

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2022

Abstract

This research is a comparative study of the typological parameters of contemporary spoken Persian language and Saravi, a main dialect of the Mazandarani language, using some Greenbergian universals as its theoretical framework in word order correlations. The study aims to determine the common parameters and the variations of specific syntactic constituents among the systems studied here. On this basis it investigates the unmarked word order in declarations, as well as preparing a systematic comparison of phrasal genitive and adjective structures in the systems under investigation, along with examining their self and possessive pronominal orders. Together with revealing the use of differential orderings within the systems in these respects throughout the paper, the findings uphold Greenberg's language universals as a useful tool in classifying language types as well as specifying the variations of the syntactic constituents.

- Type

- Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The International Society for Iranian Studies 2012

Footnotes

We wish to express our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for providing valuable comments on the paper.

References

1 Greenberg, J., “Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements,” in Universals of Language, ed. Greenberg, J. (Cambridge, 1963), 73–113Google Scholar.

2 Karimi, Simin, “Word-Order Variations in Contemporary Spoken Persian”, in Persian studies in North America, ed. Marashi, Mehdi (Bethesda, MD, 1994), 43–73Google Scholar.

3 Shahidi, Minoo, A Sociolinguistics Study of the Language Shift in Mazandarani (Uppsala, 2008)Google Scholar.

4 DabirMoghaddam, M., “majhul dar zabân-e fârsi” [Passives in Persian language], The Journal of Linguistics, 2, no. 1 (1364/1985): 31–47Google Scholar; DabirMoghaddam, M., “Internal and External Forces in Typology: Evidence from Iranian Languages,” Journal of Universal Language, 7 (2006): 29–47CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Mahutian, Shahrzad, dastur-e zabân-e fârsi az didgâh-e rade šenâsi [Grammar of the Persian language from a typological perspective], trans. Samaii, Mehdi (Tehran, 1378/1999), 38–39Google Scholar.

5 E.g. Karimi, “Word-Order Variations”; Lazard, Gilbert, A Grammar of Contemporary Persian, English translation (Costa Mesa, CA, 1992)Google Scholar; honar, Nahid Eslami, “Barresi-e Arayesh saze ha dar Farsi Goftari-e Me'yar va ta'sir ân dar Amuzesh-e Zabâne Englisi be Bozorgsâlân” [A word order study of standard spoken Persian and its effect on teaching English to adults] (unpublished thesis, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, 1385/2006)Google Scholar; Dabir-moghaddam, Mohammad and Sharifi, Shahla, “Barresie Selsele Maratebe-e Rade Shenakhti-e Marbut be Hoze-ye Arayesh-e Vazhe-ha Dar Zaban-e Farsi-e Goftari” [A study of the hierarchical typology of word order in standard spoken Persian], Journal of Literature and Humanities of Ferdousi University, No. 149 (1384/2005): 85–112Google Scholar.

6 E.g. Shahidi, A Sociolinguistics Study; Kohan, M. N., “Guyeshe saari” [Sari Dialect], Iranian Journal of Linguistics, 11, no. 1 (1373/1994): 99–101Google Scholar; Shokri, Ghiti, Guyeš-e sari (mâzandarâni) [Sari dialect (mâzandarâni)] (Tehran, 1374/1995)Google Scholar; Bashirnejad, H., “zabân-e mahaliye Iran va durnamâ-ye âyande” [Vernaculars in Iran and their future perspective], Journal of Language and Linguistics, No. 5 (1386/2006): 8Google Scholar; Bashirnejad, H., “mâzandarâni: zabân, lahje yâ guyeš,” Abakhtar Journal, No. 14 (1384/2005): 175Google Scholar.

7 Shirin Mehmanchian Saravi.

8 Greenberg, Joseph H., ed., Universals of Language, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, 1966 [1963])Google Scholar.

9 Ibid., 60.

10 Ibid., 62.

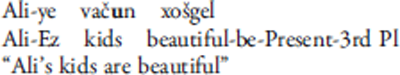

11 Ibid., 77.

12 Throughout this paper ‘a’ examples are spoken Persian and ‘b’ ones are Saravi.

13 The object markers are /-o/ and /–ro/ in Persian and /–re/ in Saravi.

14 Shahidi, A Sociolinguistics Study, 110.

15 This sign is used to represent ill-formed or ungrammatical structures.

16 While Persian includes both dependent and independent possessive pronouns, Saravi only displays the independent forms in its system, exemplified in example 11. Comparisons of self pronouns, possessive pronouns and possessive pronominal adjectives in the two systems are presented in Tables 3, 4 and 5, respectively.

17 Greenberg, Universals of Language, 62.

18 This example is the name of a mountain in Iran.

19 Greenberg, Universals of Language, 71.

20 The presence or absence of Ezafe is not a matter for consideration within the present example, where attention is focused on the order of the head noun and the subordinate (genitive).

21 Greenberg, Universals of Language, 60.

22 Ibid., 75.

23 Ali is genitive in both Persian and Saravi here.

24 Example 28b here is an ungrammatical structure, the concept of which is declared by the following sentence:

25 Greenberg, Universals of Language, 68.

26 Ibid., 68–69.

27 The sign is used to show the un-equivalency of the structures on its two sides.

28 Greenberg, Universals of Language, 71.

29 The lists of possessive adjectives are presented in Table 5.

30 Greenberg, Universals of Language, 68.

31 Greenberg, Universals of Language, 70.

32 The sign ? is used here to show the unusual sentence structure.

33 The word form “which” is not used explicitly in Saravi, but the meaning implies it.

34 In Persian the subject pronoun precedes the preposition, while Saravi uses the object pronoun without /-re/ (the object marker).

35 Though this might cause semantic changes due to the change in the degree of formality (thank you to the anonymous reviewer for pointing this out).

- 1

- Cited by