Article contents

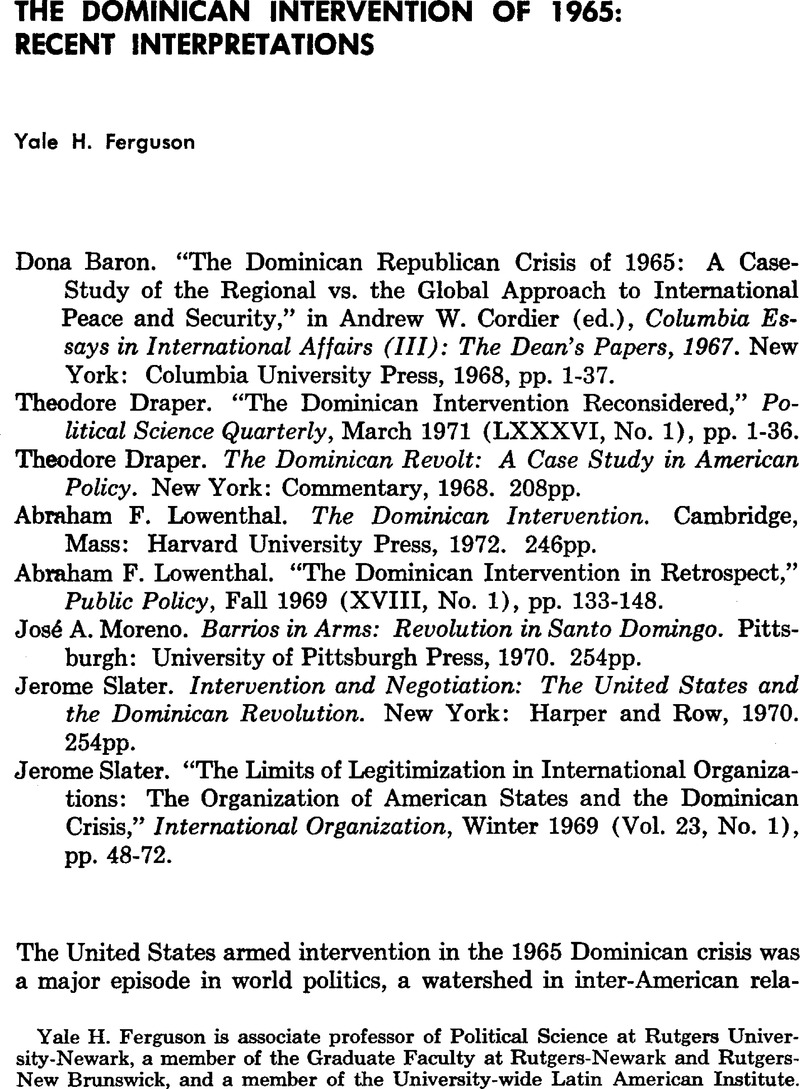

The Dominican Intervention of 1965: Recent Interpretations

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 May 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essay

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The IO Foundation 1973

References

1 The Baron, Lowenthal, and Slater articles are reprinted—along with other selections relating to the crisis by Fulbright, Senator J. William, Mann, Thomas C., Martin, John Bartlow, and Bosch, Juan—in Ferguson, Yale H. (ed.), Contemporary Inter–American Relations: A Reader in Theory and Issues (Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice–Hall, 1972).Google Scholar See also especially Szulc, Tad, Dominican Diary (New York: Delacorte Press, 1965);Google ScholarKurzman, Dan, Santo Domingo: Revolt of the Damned (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1965);Google ScholarNiedergang, Marcel, La Révolution de Saint Dominique (France: Librairie Plon, 1966);Google ScholarGeorgetown University Center for Strategic Studies, Dominican Action—1965 (Washington: Georgetown University, 1966);Google ScholarMartin, John Bartlow, Overtaken by Events: The Dominican Crisis—From the Fall of Trujillo to the Civil War (Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday, 1966),Google Scholar Part Four; Bosch, Juan, “The Dominican Revolution,” The New Republic, 07 24, 1965,Google Scholar and “Communism and Democracy in the Dominican Republic,” Saturday Review, August 7, 1965; Geyelin, Philip, Lyndon B. Johnson and the World (New York: Praeger, 1966), chap. 10;Google ScholarEvans, Rowland and Novak, Robert, Lyndon B. Johnson: The Exercise of Power (New York: New American Library, 1966),Google Scholar chap, xxiii; Roberts, Charles, LBJ's Inner Circle (New York: Delacorte Press, 1965),Google Scholar chap, xiii—and the extensive bibliographies in the works under review.

2 For an analysis of the Kennedy, and policies, Johnson, see Ferguson, Yale H., “The United States and Political Development in Latin America: A Retrospect and a Prescription,” in Ferguson, (ed.), Contemporary Inter–American Relations, pp. 348–391.Google Scholar

3 Moreno's research uncovered an extraordinary incident that occurred on April 28, which Draper says “tells as much about the U.S. intervention as any incident can.” Moreno relates: “Antonio Martínez Francisco, a rich businessman, was the Secretary General of Bosch's PRD when the revolution broke out. As a moderate, he sought mediation from the U.S. Embassy when the fighting started to get out of hand. His plea went unheard by U.S. officials. On April 28, Martínez sought political asylum in the Mexican Embassy, where he received a phone call from Arthur Briesky, Second Secretary at the U.S. Embassy, who asked him to come to the embassy to discuss important problems with W. T. Bennett. Martínez agreed, and a car arrived to take him from the Mexican Embassy. Inside the car he found a loyalist colonel and a CIA agent who took him at gunpoint to San Isidro. There he found the U.S. official who had led him into the trap, as well as U.S. air attache [Lt. Col. Thomas B.] Fishbun, surrounded by Dominican generals. He was forced to read over the radio an appeal asking the rebels to surrender their weapons.”

4 Draper insists that a general weakness of the Slater volume is that its author “wants to have his cake and eat it too,” that is, he has a “proclivity for saying one thing in one place for one purpose and another thing in another place for another purpose.” I think the problem, if any, stems from the nature of the Dominican case rather than Slater. Motives, objectives, actions, events—all were much too complex to lend themselves to the kind of neat either–or interpretations that Draper apparently finds much more satisfying.

5 See his A Revaluation of Collective Security: The OAS in Action, Mershon Center for Education in National Security Pamphlet No. 1 (Cleveland: Ohio State University Press, 1965);Google ScholarThe OAS and United States Foreign Policy (Cleveland: Ohio State University Press, 1967) chap. 2;Google Scholar and “The Decline of the OAS,” International Journal, Summer 1969.

6 “The Decline of the OAS,” p. 505.

7 “The Classifiers of Classified Documents Are Breaking Their Own Classification Rules,” The New York Times Magazine, February 4, 1973.

- 1

- Cited by