Collaboration in Mixed Home Care

Due to demographic change, many countries face the challenge of ensuring adequate care for elderly people. In Germany, more than 3 million people are currently in need of nursing care, 81 percent of whom are aged 65 years or older (1). Although 27 percent of the care-dependent elderly people live in nursing homes, more than two thirds are cared for at home, where care is accomplished by a variety of only weakly connected caregivers (Reference Granovetter2) such as relatives, friends, neighbors as well as healthcare and nursing services (Reference Eggert, Sulmann and Teubner3). To ensure the best possible care for the person in need, it is essential to coordinate all involved actors. The multifaceted and complex task of organizing and coordinating the various supporting caregivers is usually performed by a caring relative (Reference Renyi, Rosner, Teuteberg, Kunze, Abramowicz and Corchuelo4) for whom daily care is usually already an enormous burden. Therefore, technological support can be a great benefit particularly for informal caregivers and can thus strengthen care networks (Reference Renyi, Rosner, Teuteberg, Kunze, Abramowicz and Corchuelo4).

Computer-Supported Collaborative Care (CSCC)

The research field of CSCC is particularly concerned with the question of how technology can support entire care networks for the elderly living at home. In contrast to the research field of computer-supported collaborative work (CSCW), the focus of CSCC is more on a person than on a shared objective (Reference Consolvo and Roessler5), and aspects such as emotions, trust, privacy, and so on are considered more important (Reference Consolvo and Roessler5) than increases of efficiency and effectiveness of work processes. Unlike in large health facilities, the use of technology is less common in mixed home and community care, although several studies point to its importance and potential for the networking of caregivers (Reference Winge, Wangler, Johansson, Nyström, Waterworth, Bath, Day and Norris6–Reference Phung, Hoang, Lawrence, Cappello, Wang and Buyya13).

In home care, the telephone is still the predominant medium of communication, supplemented by numerous handwritten memos at the patient's home (Reference Renyi, Teuteberg, Kunze, Abramowicz and Paschke14). Applications that help to organize the daily care work and coordinate the caregivers involved can therefore contribute significantly to improving mixed home care situations (Reference Fabiano, de Carvalho, Tellioğlu, Hensely-Schinkinger, Habiger, de Angeli, Bannon, Marti and Brodin15).

The recognition of this potential has led to the development of a variety of care collaboration software tools for mixed home care (Reference Renyi, Kunze, Rau, Rosner, Gaugisch, Pfannstiel, Krammer and Swoboda16), including research prototypes such as CareBetter (17), Cuidador Acvida (Reference Garcia and de Lara18), and Zirkel (Reference Renyi, Teuteberg, Kunze, Abramowicz and Paschke14) as well as commercial applications such as Carezone (19), Jointly (20), and CaringBridge (21). In the United States of America (USA), Carezone claims to have more than 5 million application installations. Despite strong efforts to create the necessary software that is adapted to the target group (Reference Verdezoto, Wolff Olsen, Luo, Liu and Yang22–Reference Baldissera, Camarinha-Matos, Afsarmanesh, Camarinha-Matos and Soares26), the adoption of such technologies in Europe is still relatively low. The most widespread European app, Jointly, only has 1,000+ installations from the Android Play Store (access date: 28 May 2019) (27).

The introduction of technological support systems into mixed home care constitutes a complex challenge, as varying expectations of different actors (patients, informal and professional caregivers, and society) have to be matched (Reference Renyi, Rosner, Teuteberg, Kunze, Abramowicz and Corchuelo4;Reference Craig, Dieppe, Macintyre, Michiel and Petticrew28). The complexity of the introduction of technological applications in the healthcare sector can be evaluated by means of a systematic framework. In 2017, Greenhalgh et al. (Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton, Papoutsi, Lynch, Hughes and A'Court29) presented a new framework for theorizing and evaluating Non-adoption, Abandonment and challenges to the Scale-up, Spread and Sustainability of health and care technologies (NASSS), based upon their own studies as well as other theoretical frameworks. The NASSS framework (Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton, Papoutsi, Lynch, Hughes and A'Court29–Reference Greenhalgh and Abimbola31) includes seven domains: “the condition or illness, the technology, the value proposition, the adopter system (comprising professional staff, patient, and lay caregivers), the organization(s), the wider (institutional and societal) context, and the interaction and mutual adaptation between all these domains over time” (Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton, Papoutsi, Lynch, Hughes and A'Court29). Therefore, the framework takes into account not only the specifics of the respective networks, but also the aspects associated with the introduction of the new technology and the consequences that may lead to changes during implementation.

It is also assumed that the more complex the individual domains are, the less likely it is that the technology will achieve sustainable acceptance across the system. Thus, the framework was designed to capture the complexity and provide appropriate handling support (Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton, Papoutsi, Lynch, Hughes and A'Court29–Reference Greenhalgh and Abimbola31).

Motivation, Aims, and Research Questions

In a participatory design process, in which nurses, neighborhood helpers and caring relatives had been involved, the authors of this paper developed a collaboration prototype for mixed home care (Reference Renyi, Teuteberg, Kunze, Abramowicz and Paschke14). However, several barriers hampered the evaluation beyond screen-based prototype testing. Despite a broad recruiting strategy, only some caregivers could be encouraged to evaluate the prototype. But as the commitment of entire care networks was lacking, field tests failed several times, as did the adoption and scale-up. Some field tests had to be aborted prematurely because the health status of patients deteriorated or patients deceased.

These difficulties motivated the authors to closer examine the current state of mixed home care collaboration application (mHCA) evaluation. Methodological aspects of studies were investigated with regard to evaluation instruments, recruiting strategies, and objectives. Further analysis of the identified interventions regarding non-adoption, abandonment, and other challenges was conducted using the NASSS framework.

Our primary research question thus is: How are mHCA evaluated in the literature and how can previous experience be assessed using the NASSS framework? The discussion section of this paper summarizes the results as concretized NASSS model for mHCA for elderly mixed home care.

Methods

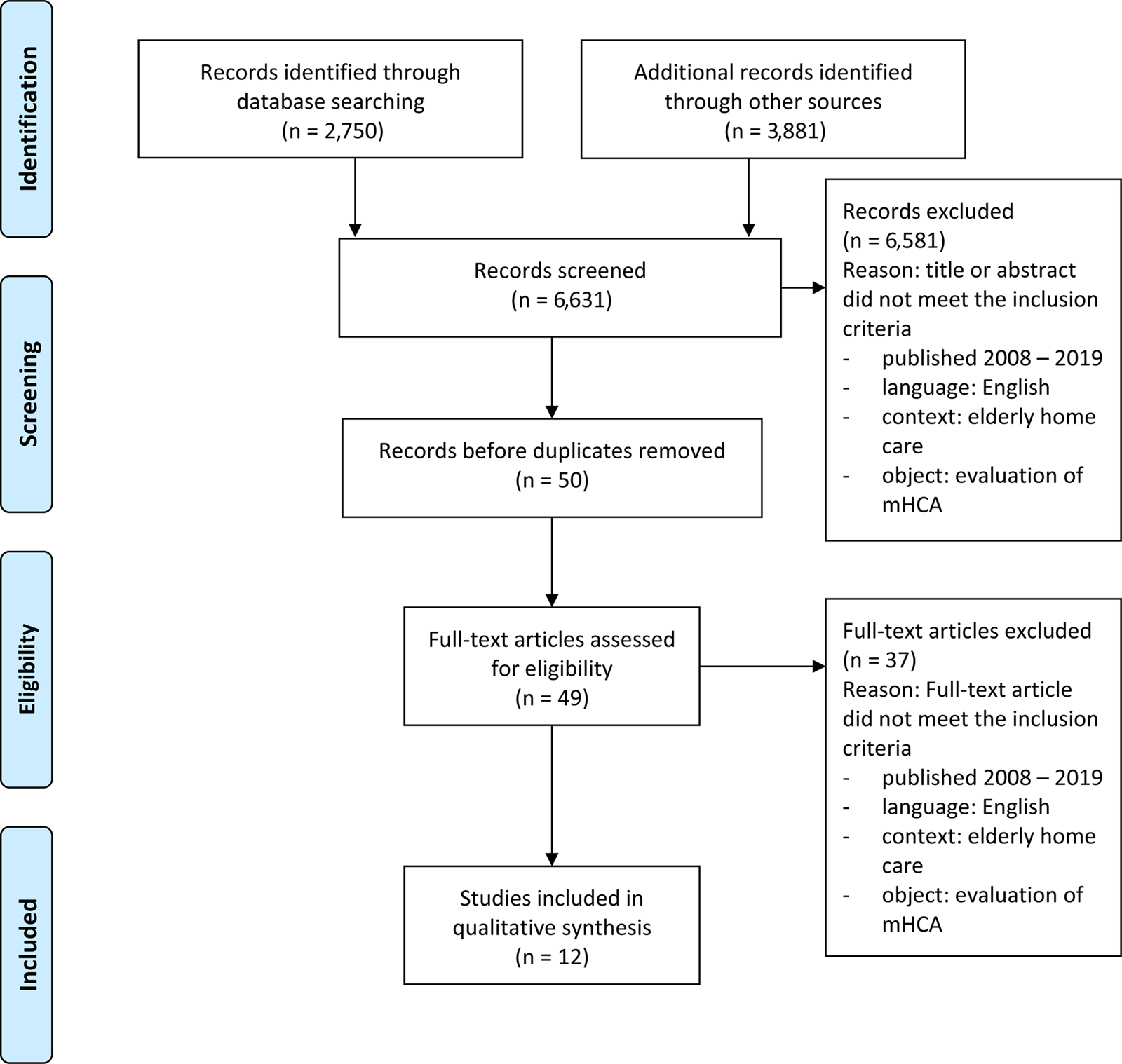

In spring and summer 2019, a systematic literature review was conducted using five bibliographic databases (SpringerLink, IEEE Explore, PubMed, Compendex, and ScienceDirect), based on the PRISMA guidelines (Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman32), to identify literature published about mHCA and their evaluation. Although various study results may also be applicable to other home care contexts, the inclusion criteria for studies to be included in this contribution were defined as follows. The studies had to focus on collaboration in home care networks for elderly people, must be written in English and published between 2008 and 2019.

A broad search strategy was employed including the words “(elderly/long-term/home) care,” “collaboration/coordination/organization,” and “application/intervention.” Additionally, a market research revealed nineteen applications available in mobile application stores and on Web sites. Their evaluations were searched using the Google Scholar search engine. The complete search strategy is described in the Supplementary Material.

For study selection, the first author screened the literature databases and applied the inclusion criteria to all titles and abstracts retrieved from the searches, and then added relevant articles for deeper analysis. Independently of each other, the first three authors read all full-text articles and excluded those that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thereby, the authors came to identical results. The study selection process is presented in a PRISMA flow chart (Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman32) in Figure 1. The appraisal tool “CASP Qualitative Checklist,” (33) by the “Critical Appraisal Skills Programme,” was used to validate the quality of the selected papers. The checklist was not designed as a scoring system, but as a guide for systematical considerations on the quality of studies. The first two questions (clear formulation of the research aims and appropriateness of methodology) are screening questions to determine whether to proceed with the analysis. All included studies passed this test.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow-chart of literature selection according to Moher et al. (Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman32).

Data extracted from the papers included source, date of publication, title, authors, name of application, country of evaluation, study design, description of application, and summarized results.

Results

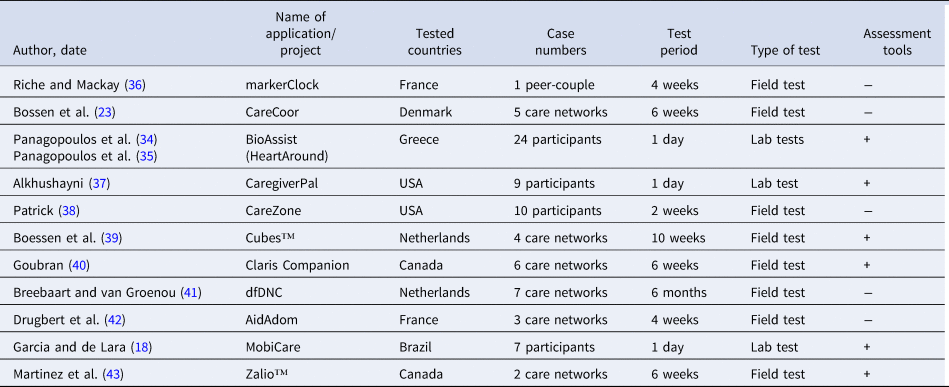

The systematic search identified 2,750 papers whose titles and abstracts strongly relate to healthcare collaboration. Additionally, 3,874 papers were identified through the search engine Google Scholar. Seven other studies were identified through snowball search. A total of 6,581 papers were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. After duplicate removal (n = 1), the abstracts of forty-nine papers indicated a possibility of reporting on mHCA, the assessment of which resulted in twelve relevant studies which again evaluated eleven different applications. If an application was mentioned in several studies, only the original evaluation report was included. As Panagopoulos et al. (Reference Panagopoulos, Kalatha, Tsanakas, Maglogiannis, de Ruyter, Kameas, Chatzimisios and Mavrommati34;Reference Panagopoulos, Menychtas, Tsanakas and Maglogiannis35) evaluated, redesigned, and re-evaluated their application, both evaluation studies were included in the analysis. See Table 1 for an overview of included studies.

Table 1. Identified applications for care collaboration

Study Designs

All studies emphasize the importance of involving future users in the development process. To create target group specific applications, interviews, workshops, and usability tests were conducted. However, in terms of sample size, duration and type, the evaluations vary widely. Four studies (Reference Garcia and de Lara18;Reference Panagopoulos, Kalatha, Tsanakas, Maglogiannis, de Ruyter, Kameas, Chatzimisios and Mavrommati34;Reference Panagopoulos, Menychtas, Tsanakas and Maglogiannis35;Reference Alkhushayni37) used 1-day usability workshops, whereas another study (Reference Breebaart and Broese van Groenou41) observed the usage of an application for more than 6 months. All applications were tested without randomized control groups or pre-post comparisons.

Objectives

Most of the studies included in this analysis investigated the usability of the application technology. For this purpose, three studies used the System Usability Scale (SUS) (Reference Panagopoulos, Kalatha, Tsanakas, Maglogiannis, de Ruyter, Kameas, Chatzimisios and Mavrommati34;Reference Panagopoulos, Menychtas, Tsanakas and Maglogiannis35;Reference Martinez, Ye and Mihailidis43) and one the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ) (Reference Boessen, Verwey, Duymelinck and van Rossum39). In an attempt to evaluate additional changes triggered by the introduction of the technology, Martinez et al. (Reference Martinez, Ye and Mihailidis43) investigated caregiver self-efficacy (using a revised scale for caregiving self-efficacy), burden of care (using a short version of Zarit Burden Interview — ZBI) and family structures (using the General Functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device — FAD).

Recruiting Strategy

According to the studies, the recruiting was carried out by the project partners or professional nursing staff (Reference Boessen, Verwey, Duymelinck and van Rossum39;Reference Breebaart and Broese van Groenou41;Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42), word-of-mouth advertising, advertising flyers, and social media posts. Due to the stigmatization of the term “elderly,” one study reported that recruiting older participants was rather difficult, partly because the persons saw no direct benefit for themselves (Reference Riche and Mackay36).

In general, anyone with a connection to elderly care could take part in the tests. Only one study (Reference Goubran40) reported a standardized assessment during the recruiting phase to evaluate participants for study eligibility. One study (Reference Boessen, Verwey, Duymelinck and van Rossum39) aimed at a broad heterogeneity, whereas another (Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42) preferred a homogeneous sample. Overall, however, the selection of participants was convenient.

Nature of Intervention

Condition

The essential inclusion criterion for all studies was the focus on home care for elderly people. The respective characteristics of the care situation can vary significantly depending on the health status (physical and mental state) and the life situation of the respective patient, which greatly influences the care network, the potential adopters of the new technology as well as the applicable technology. Therefore, four studies narrowed the focus to specific conditions (patients with dementia (Reference Boessen, Verwey, Duymelinck and van Rossum39;Reference Goubran40;Reference Martinez, Ye and Mihailidis43); patients with multiple chronic conditions (Reference Alkhushayni37)).

Technology

All evaluated technologies support some form of communication. However, the complexity of the systems varied considerably and ranged from simple communication (Reference Riche and Mackay36) to complex health documentation features (Reference Panagopoulos, Kalatha, Tsanakas, Maglogiannis, de Ruyter, Kameas, Chatzimisios and Mavrommati34;Reference Panagopoulos, Menychtas, Tsanakas and Maglogiannis35). In general, the evaluated applications support collaboration through shared calendars and messages.

Seven studies examined research prototypes. Given that prototypes are inherently immature and generally more prone to unexpected disturbances, the authors reported difficulties, such as instability, uneven performance and low interoperability. Irrespective of the prototype status of the application, it is essential that all components are reliable (Reference Bossen, Christensen, Grönvall and Vestergaard23).

The study comparison showed varying requirements for interoperability, data protection, and stability. None of the systems allowing the exchange of medical information achieved sufficient interoperability with pre-established healthcare and documentation systems, which led to extra work for nurses and, consequently, a reduced usage of the tested systems. On the other hand, when less health-specific aspects were included, the benefits of the mHCAs decreased and they did not stand out from standard communication applications. Privacy concerns are often secondary to the user experience for informal caregivers, which conflicts with the necessity of professional stakeholders who have to adhere to privacy regulations.

Nine studies discussed the ways in which knowledge about system use can be communicated to the users. Although some studies argue that the technology design itself must be simple and easy to use (Reference Panagopoulos, Kalatha, Tsanakas, Maglogiannis, de Ruyter, Kameas, Chatzimisios and Mavrommati34;Reference Panagopoulos, Menychtas, Tsanakas and Maglogiannis35); professional caregivers often prefer formal training to ensure effective work processes (Reference Bossen, Christensen, Grönvall and Vestergaard23).

Value Proposition

The value propositions of commercial service providers were not addressed in the examined studies. Seven of the eleven applications were prototypes and therefore did not present or discuss business models. In the studies, the focus was more on the evaluation of the technology rather than on its potential benefit. The studies were conducted to gain knowledge about value propositions to use for future scaling (Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42), among other purposes. Only one study, Martinez et al. (Reference Martinez, Ye and Mihailidis43), attempted to validate specific value propositions (including perceived self-efficacy and caregiver burden) using standardized assessment tools.

Little information was reported about participants' motivation to take part in the studies. Riche and Mackay (Reference Riche and Mackay36) stated that their participants attended out of “curiosity about the sociological aspects of communication technology.” In general, the participants exhibited a cautious attitude regarding their expectations of the application prior to the test (Reference Goubran40). Some users recognized benefits during the tests, whereas others did not name benefits even after the test ended (Reference Boessen, Verwey, Duymelinck and van Rossum39).

In summary, the studies found that participants were able to organize themselves more easily and empathize better with the care situation overall (“peace of mind”) when using assistive technology. However, despite many such positive reports, all studies concluded that the impact of technology use on care arrangements remains unclear, making it difficult to argue for the use of technology. Eight studies concluded that large-scale platform testing is still needed to demonstrate the usefulness and perceived value of application interventions.

Furthermore, other digital organizing tools, including calendars (Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42) or WhatsApp (Reference Breebaart and Broese van Groenou41), were already in use for care collaboration. The various ways to share information (e.g., test applications, the professional agencies' intranet tools as well as the medical reports at the patients' homes (Reference Breebaart and Broese van Groenou41)) reduced the added value of the mHCA and confused the test users.

Adopter System

All the applications addressed were designed to support collaboration in mixed home care. In nine of the eleven applications also the care recipient was explicitly encouraged to use the system and participate. In fact, three of these applications required the patients to play an active role in the use of technology (Reference Garcia and de Lara18;Reference Panagopoulos, Kalatha, Tsanakas, Maglogiannis, de Ruyter, Kameas, Chatzimisios and Mavrommati34;Reference Panagopoulos, Menychtas, Tsanakas and Maglogiannis35;Reference Goubran40). With the exception of one application with a tandem structure (Reference Riche and Mackay36), all the others allowed for a flexible number of caregivers. However, only six of twelve studies included all targeted adopter groups.

Generally, the studies faced several limiting factors (e.g., deceased patients (Reference Bossen, Christensen, Grönvall and Vestergaard23) and low technical competence of adopters (Reference Garcia and de Lara18)). The heterogeneity of caregivers led to diverging requirements (Reference Bossen, Christensen, Grönvall and Vestergaard23).

Health/Care Organization(s)

Furthermore, the studies reported several difficulties, which can be traced back to institutional organization structures. The organizations have only half-heartedly participated in the studies. Not all necessary actors were informed and trained (Reference Bossen, Christensen, Grönvall and Vestergaard23), no official equipment was purchased for the test (Reference Breebaart and Broese van Groenou41), and the nurses used the technology in their free time without being paid for this work (Reference Boessen, Verwey, Duymelinck and van Rossum39). Therefore, although the organizations were basically interested in participating and testing, these examples make the willingness to introduce such a technology appear doubtful.

There are many different providers for the home care sector (such as pharmacies, physiotherapists, doctors, medical supply stores, and mobile foot care). However, there is a lack of professional case managers who would coordinate these services in a meaningful way. This is usually done by the caring relatives, as the individual professional actors do not take over such coordinating tasks as they are not paid for them. Due to this lack of professional coordination, problems related to “limited resources for articulation work and basic information sharing requirements” (Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42) arise.

Wider System

As can be seen from Table 1, the studies originate from Europe (seven studies from France, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Greece) and North and South America (five studies from the USA, Canada, and Brazil). Although demographic change also affects developing countries, no studies from these countries were identified.

Privacy is a major topic in all studies, although it relates more to ethical than legal aspects. This could be explained by the fact that mHCAs “have fewer privacy problems than eHealth and care records” (Reference Breebaart and Broese van Groenou41). There is a conflict between the need to preserve “medical privacy” and the need to present information in a way that allows to derive practical tasks (Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42).

Of all included studies, only Drugbert et al. (Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42) discuss aspects of interoperability between information infrastructure, sustainability, and governance. They suggested that interoperability is not only linked to “technical interoperability and synchronization issues but also requires to engage work on professional and local categorization schemes” (Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42). Collaboration platforms involve several autonomous but not hierarchically bound organizations, which renders governance discussions necessary.

Embedding and Adaptation over Time

Five studies (Reference Panagopoulos, Kalatha, Tsanakas, Maglogiannis, de Ruyter, Kameas, Chatzimisios and Mavrommati34;Reference Panagopoulos, Menychtas, Tsanakas and Maglogiannis35;Reference Patrick38;Reference Goubran40;Reference Martinez, Ye and Mihailidis43) evaluated four market applications. The main focus of these evaluations was on usability aspects in lab studies. Although the evaluations focus on adapting the technology to meet individual needs over time, effects of embedding technology in care routines and adoption of care networks are not investigated.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review is to identify and compare evaluations of mHCAs and to determine possible implications of these evaluations regarding the practical use of mHCAs. The NASSS framework proved to be a useful tool to structure the results, reveal specific problems, and clarify the complex interrelationships of all domains.

Analyzing the Complexity of mHCA Implementation

Table 2 summarizes the observed particularities that contribute to the complexity of mHCA implementations in a concretization of the NASSS framework. This should help researchers to better understand the complexity of future mHCA implementations and facilitate the evaluation of individual characteristics of the different home care scenarios. The table has three columns. The first column contains the original NASSS domain, the second the derived concretization for the mHCA use case, and the third the factors that contribute to the complexity of the implementation. Respective references are indicated for the factors originating from examined studies, the other factors represent the authors' own experiences. The table reads as follows: the first domain “condition” is concretized to “home-dwelling elderly.” The nature of the condition is frailty. The implementation of mHCA is complex if there is an age-related decline in the elderly's condition. Cognitive health issues as well as motor, visual, or other functional impairments can constitute comorbidities of the home-dwelling elderly. For example, high functional impairments can make mHCA implementations complex, when these hinder the elderly to use standard technology. The spatial closeness of caregivers is a mentioned socio-cultural condition. Missing closeness may increase the necessity for using mHCA. However, a lack of people who can provide personal support complicates the implementation of mHCA. Further factors such as missing infrastructure are also conceivable but were not investigated in the studies. Primarily, mHCA are meant to make better use of existing resources. In regions where there is a lack of family doctors, these network positions remain unfilled and can – of course –, not be compensated by the system. Which technologies (domain 2: mHCA) are conceivable for a technology implementation and which value propositions (domain 3) can be foreseen is, however, strongly influenced by the “adopter system” (domain 4) — the “care network.” Depending on the “condition” of the patients, the composition of care networks change. The composition as well as the number of caregivers further leads to varying degrees of complexity. A special group is represented by the “health/care organizations” (domain 5).

Table 2. Domains and factors contributing to complexity of mHCA implementation

The specification of the domain “value proposition” proved to be difficult, because aspects such as peace of mind (Reference Bossen, Christensen, Grönvall and Vestergaard23;Reference Riche and Mackay36), shared responsibility and awareness (Reference Riche and Mackay36;Reference Boessen, Verwey, Duymelinck and van Rossum39;Reference Breebaart and Broese van Groenou41;Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42), and community connectedness (Reference Riche and Mackay36;Reference Alkhushayni37;Reference Boessen, Verwey, Duymelinck and van Rossum39;Reference Goubran40;Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42;Reference Martinez, Ye and Mihailidis43) are desired but not necessarily achievable, or concretely measurable outcomes. Complexity in this domain may rise when the actors perceive the benefits very differently.

The lack of prerequisites makes the domain “wider system” complex. If there were community-based care models and reimbursement for care coordination tasks, the complexity of introducing mHCA would be significantly lower.

Finally, the degree of implementation affects the complexity of the mHCA implementation. Although answering usability questions in lab studies can be relatively simple, questions about actual care networks may be considerably more complex. Unanswered questions, for example, about interprofessional and interorganizational incentives for networking can only be answered in real-life situations. Due to the limited scope of the field studies, it can be assumed that most of the contributions to complexity in domains 6 and 7 are still not evident and unclear.

Limitations

Similar to any scientific work, also this contribution has some limitations. For one thing, the literature review only found twelve studies that met the inclusion criteria, which may be due to the fact that only studies in English were included. As national laws, practices, and traditions shape health care, there may be more publications in other languages. Furthermore, by only including publications between 2008 and spring 2019, relevant publications covering evaluations of mHCA interventions outside that period may have been missed. Nevertheless, the period was deliberately chosen to minimize technology bias. Furthermore, due to the specific focus of this study, numerous studies analyzing solely the needs and requirements of technology introductions could not be considered.

Practical Implications

This analysis suggests that mHCA are capable of reducing the psychological burden on informal caregivers (“peace of mind” (Reference Bossen, Christensen, Grönvall and Vestergaard23)) but that the applications can only develop their full potential if they are used in large networks involving various interdisciplinary actors (Reference Drugbert, Labadie and Tixier42). However, because it is not yet clear whether electronic communication will create additional workload in terms of hours and other types of informal help, or whether it rather ameliorates the quality of life of patients and caregivers (Reference Breebaart and Broese van Groenou41), researchers have so far refrained from drawing implications for practice. Depending on the condition of the elderly patients living at home as well as their care networks, the advantages of a simple communication system may outweigh complex collaboration systems. Further research is needed to examine the impact of using mHCA on the care burden of informal caregivers, the quality of care and quality of life of the home-dwelling elderly (Reference Breebaart and Broese van Groenou41). For example, the use of “Smart Toys” (Reference Garcia and de Lara18) may stimulate and facilitate proactive interaction among elderly patients and mHCA interventions may be particularly useful for informal caregivers (Reference Garcia and de Lara18). However, as long as the systems are at the prototype level and no seamless interoperability with existing digital communication and coordination tools is in place, these applications cause extra effort and are unlikely to be adopted. To solve “infrastructural work” (Reference Gui, Chen, Brewster and Fitzpatrick44) problems and thus provide a systemic basis for the introduction of the technology, examples, such as the Buurtzorg model (Reference Nandram, Nandram and Bindlish45) should be consulted.

Implications for Research

Several publications address the target group's needs and requirements with design proposals (c.f. (Reference Renyi, Rosner, Teuteberg, Kunze, Abramowicz and Corchuelo4;Reference Verdezoto, Wolff Olsen, Luo, Liu and Yang22;Reference Schorch, Wan, Randall and Wulf24;Reference Bratteteig, Wagner, Bertelsen, Ciolf, Grasso iMaria and Papadopoulos46)), but due to low maturity levels, the adoption aspects are rarely evaluated. Additional research is needed to examine the change processes that accompany the adoption process of home care-specific collaboration applications.

The design and implementation of new technology is time-consuming and difficult, thus, evaluations of prototypes are rare. In addition, it is most likely that reports of unsuccessful field studies are not published. Research investigating change management in the adoption of new technologies needs to be given higher priority to close the gap between commercially successful applications and the scientific proof of the effect of such applications.

The need to enhance collaboration in mixed home care is evident, but the use of care-specific technologies and their positive impacts on the stabilization of care arrangements has yet to be demonstrated. Because field tests with target networks have proven difficult, it could be helpful to investigate the user experience of successful application launches (e.g., by text-mining user rating posts) to support the further development of mHCA and promote their positive effects in Europe. Further analysis and categorization of care networks could help to identify those care network types that are more receptive to technology use and usage benefits. More specific testing could then be carried out in networks with high usage potential and the tests could be evaluated using standardized assessment instruments.

It is unclear whether care-specific software is needed or whether general collaboration tools would provide the same value. In addition, practical implementation issues still need to be clarified, for example, who would ideally operate a care-specific software platform.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462320000458.

Funding

This review is part of the research project EIKI — Einflussfaktoren zur erfolgreichen Implementierung einer mobilen Applikation zur Kooperationsunterstützung in informellen Versorgungsstrukturen—which is funded by the Ministry for Social Affairs and Integration Baden-Württemberg.

Conflict of Interest

None.