In her novel Street of Steps (Rehov ha-Madregot), published in Hebrew in the mid-1950s, the Israeli author Yehudit Hendel chose to locate a love story between a Sephardi man and an Ashkenazi woman on one of the streets that crossed the Wadi Salib neighborhood in Haifa.Footnote 1 Hendel’s book was published against the background of the demographic changes that followed the 1948 war and the Nakba in Haifa, as thousands of Middle Eastern and North African Jewish migrants (Mizrahi Jews) settled in the eastern area of the city, which during the British Mandate had been a shared Arab-Jewish space.Footnote 2 Hendel described the streets that dissected this area as “winding alleyways of steps leading to the upper city of Haifa. Alleys without sidewalks and with old homes inhabited by a poor population.”Footnote 3 On July 8, 1959, four years after Hendel published her book, ethnic and social protests erupted in this cluster of impoverished neighborhoods, led by Jewish migrants from Morocco. In public discourse these protests were described as having an ethnic character, and accordingly were known not only as the Wadi Salib events or riots, but also as the Mered ha-Marokaim (Revolt of the Moroccans).Footnote 4

The protests in Wadi Salib erupted on the night of July 8 after police shot and injured Akiva Yaakov Elkrif, a Moroccan-born migrant. Hundreds of residents of the neighborhood, led by the Union of Migrants from North Africa (Irgun Likud ‛Oley Tsfon Afrika), clashed with the police, who fired shots into the air to disperse the protesters. The next day, the demonstrations escalated: police were pelted with stones; cafés, a bank, and buildings associated with the Mapai party and the Histadrut (labor union) were damaged; shop windows in the adjacent Hadar HaCarmel neighborhood were shattered; and cars were set on fire.Footnote 5 Throughout July, the demonstrations spread to other cities with high concentrations of migrants from Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) countries, particularly Be’er Sheva, Acre, Tiberias, and Migdal HaEmek. On July 31, protests in Wadi Salib resumed for several days following the arrest of the leaders of the union.Footnote 6

The Moroccan-Jewish protest in Wadi Salib, the Iraqi-Jewish protest in the transit camps (ma‛abarot) in the early 1950s, and the Black Panthers protest movement that erupted in Jerusalem in the early 1970s became emblematic of Mizrahi protests in Israel.Footnote 7 In the historiography of these protests, the Wadi Salib events have been mainly studied in the context of the absorption of Jewish migrants from MENA countries in Israel.Footnote 8 However, as Yfat Weiss has shown, the 1959 protests also should be examined as part of the “long history” of both the Mizrahim and of the Wadi Salib neighborhood prior to 1948.Footnote 9 This article will focus on the experience of Jewish children who grew up in this area and will ground the examination of the history of Wadi Salib in the 1950s and 1960s during the Mandate period, including the shared Jewish and Arab space that existed in the eastern part of Haifa.Footnote 10

During the Mandate period, the area around Wadi Salib, including the mixed Jewish-Arab neighborhoods of Harat al-Yahud and Ard al-Yahud, was already a focus of deprivation in general, and among children in particular.Footnote 11 The characteristics of Wadi Salib and the surrounding area changed following the 1948 war, the establishment of the State of Israel, and the Nakba. These changes were the result of the uprooting of Palestinian residents, who became refugees, and the arrival of Jewish migrants who settled in the abandoned Arab houses. In the 1950s, deprivation continued to be evident in the neighborhood, particularly among children, as manifested in phenomena such as school dropouts, vagrancy, and delinquency.Footnote 12 This article does not focus on the manner in which the Mizrahi children were perceived by social or educational bodies.Footnote 13 Rather, it seeks to use the findings of these bodies to examine how the poverty and deprivation experienced by the children of Jewish migrants from Morocco were among the main factors that led to the eruption of the protests in the summer of 1959.Footnote 14 These children, ages between six and fourteen, were active participants in the protests.Footnote 15 As migrant children, they were in a liminal stage, not only because of the neighborhood in which they lived and grew up but also because of the transitional phase they were experiencing, which entailed both migration and maturation.

The focus on the children of Wadi Salib invites an examination of the connection between protest and space, and of the character of Wadi Salib and the surrounding area, including its street steps and alleys, as a socioeconomic and cultural liminal space.Footnote 16 Wadi Salib was located between the western middle-class neighborhood of Hadar HaCarmel and the Arab and Mizrahi neighborhoods of downtown Haifa, and this borderline character was reflected not only in the geographical and topographical dimension, but also in an ethnic and cultural sense. For the children in this area, the liminal character of the neighborhood, which was particularly apparent during the events of the summer of 1959, represented not only a process of progress and change, for example from childhood to adolescence, or an emotional and psychological experience, but also an arena for an encounter between cultures, communities, and identities.Footnote 17 Wadi Salib was a neighborhood defined by physical and imagined boundaries, but as Bjørn Thomassen noted in his study of the history of the concept of liminality, borders and boundaries are there to be confronted.Footnote 18 As I will discuss in the closing section of this article, the children of Wadi Salib, who like their parents were trapped in their impoverished liminal neighborhood, moved up and down the street steps and alleys, crossing and challenging the ethnic, class, and cultural boundaries that separated downtown Haifa from the upper city and Wadi Salib from Hadar HaCarmel.

From Harat al-Yahud to Wadi Salib

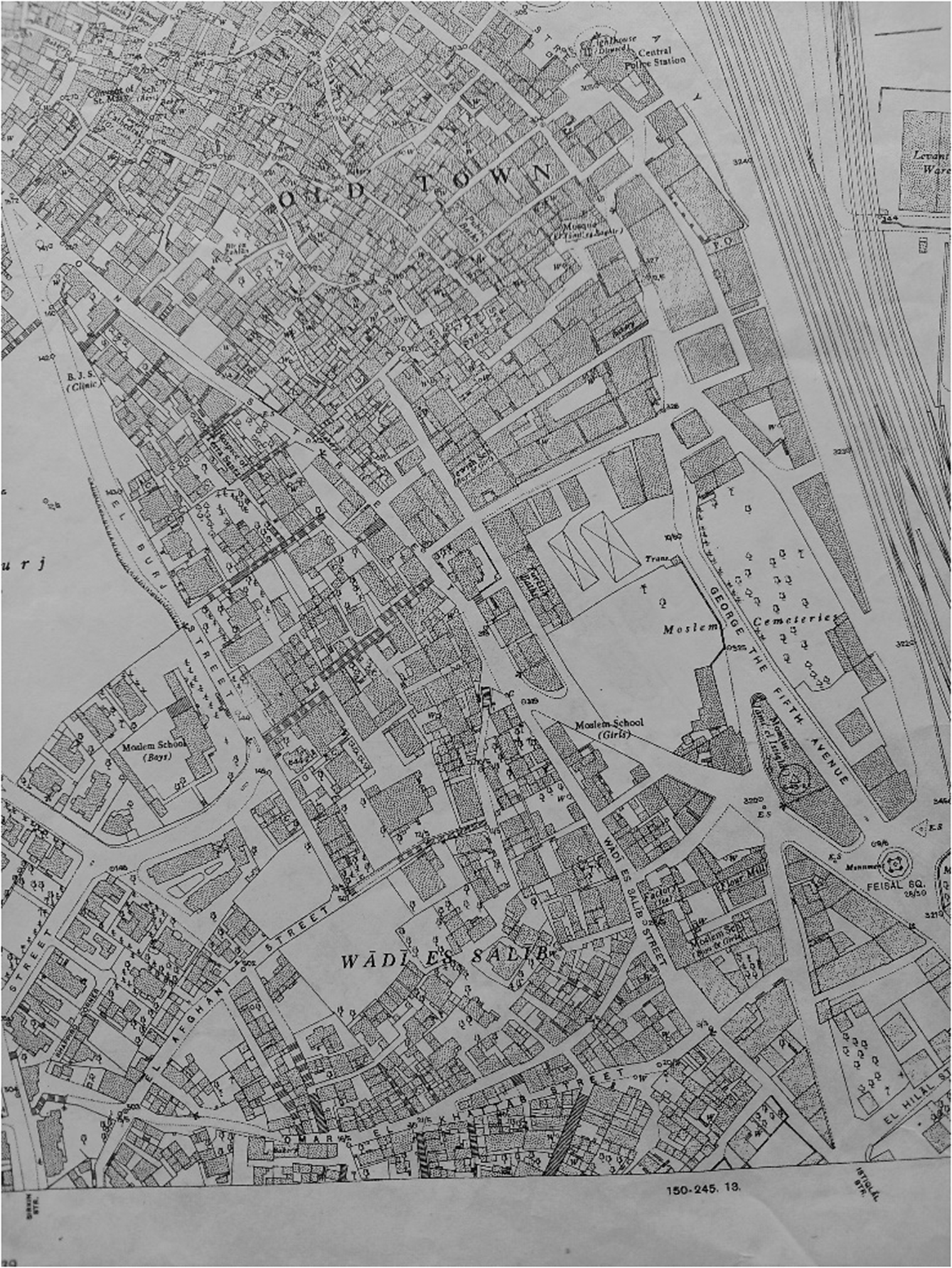

Wadi Salib was founded in the late 19th century in the eastern part of Haifa.Footnote 19 The population of the neighborhood was mainly Muslim, but until the outbreak of the 1948 war there also was a Jewish minority in the area numbering several dozen families.Footnote 20 Due to its topographical character and the deep dry river bed that dissected the neighborhood, Wadi Salib developed as a fabric of stone houses, narrow alleyways, and long street steps. Two main roads crossed the neighborhood: Omar ibn al-Khattab and Wadi Salib Street; the latter connected Stanton Street and Iraq Street. The neighborhood was bordered to the west by the Burj area and to the south by Hadar HaCarmel (Fig. 1). Since the Mandate period, the distinction between the bottom and the top of the street steps in the neighborhood had been a recognized feature of the area. Most of the wealthy Arab residents lived in the upper, western section of Wadi Salib; examples included the family of former Mayor `Abd a-Rahman al-Hajj, the author `Abd al-Latif Kanafani, and Muhammad Murad, who served as mufti of Haifa in the early years of British rule.Footnote 21 The population in the lower section of the neighborhood, around the bottom of the street steps, was poorer, including Arab migrants and laborers who came to the city from the surrounding towns and villages and from the neighboring Arab countries. This migration to Haifa, a city that gained the nickname “Umm al-Gharib” (Mother of the Stranger), began in the late Ottoman period with the settlement of Arab migrants from Nablus in the lower part of Wadi Salib.Footnote 22 The migration of rural migrants to Wadi Salib and eastern Haifa intensified in the mid-1930s with the development of the port and refineries, and continued into the 1940s with the construction of British military camps.Footnote 23 The lower section, around Stanton Street, the al-Pasha compound, and Faysal Square, also featured coffee houses, workshops, and the al-Istiqlal Mosque, opened in 1924.Footnote 24

Figure 1. Map of Wadi Salib and the Old City (Harat al-Yahud is the area around the synagogues marked within the Old City). University of Haifa Map Collection, Map 2-R-Haifa-A-2-150-245.9-1949 C.3.

Wadi Salib also bordered on Harat al-Yahud and Ard al-Yahud, two Jewish neighborhoods that also had Arab inhabitants. Harat al-Yahud was established in the first half of the 19th century by Jewish migrants from North Africa who settled in the Muslim quarter of Haifa. They were joined by Jewish migrants from Syria, Turkey, and the Balkans, and in the late 19th century some of the residents initiated the establishment of Ard al-Yahud, the first Jewish neighborhood established outside the walls of the city.Footnote 25 With the outbreak of the Arab Revolt in 1936, Jewish residents from the two neighborhoods fled to Hadar HaCarmel, and in July 1938 the Jewish evacuation of the two neighborhoods was completed. However, during the 1940s, Jews returned to live in the vicinity of these two neighborhoods, although the focal point of the Jewish population shifted to the area around Hashomer Street, to the east of Wadi Salib.

Harat al-Yahud, Ard al-Yahud, and Hashomer Street, which were all close to Wadi Salib and formed part of the shared Jewish-Arab space, acquired the character of impoverished neighborhoods during the Mandate period. Deprivation and poverty were evident in the condition of the children in the neighborhood, including the phenomenon of children of elementary school age who dropped out of studies.Footnote 26 The reasons for this phenomenon in Tel Aviv, as has been discussed by Tammy Razi, included the inability of families to cover tuition fees, the lack of suitable educational frameworks for children who were defined as having learning difficulties, and the need for children to work to help support their families.Footnote 27

The phenomenon of abandoned children, also referred to in public discourse as “street children” (yaldey rehov) or “abandoned children” (yeladim ‛azuvim), was associated in Jerusalem and Haifa with the children of Jewish migrants from the Middle East and North Africa. In the late 1930s, the Social Work Department (Ha-Mahlaka le-‛Avoda Sotsyalit) of the National Council (Ha-Va‛ad ha-Leumi), the main representative organization of the Jewish community in Palestine (the Yishuv), estimated that of some 2,000 children in Jerusalem ages six to eleven who were defined as street children or abandoned children, approximately 1,700 came from families that originated in Arab and Muslim countries.Footnote 28 The problem of street children formed part of the public discourse that questioned the national consciousness of the Sephardi and Oriental Jewish communities and their participation in the Zionist enterprise. In Haifa, where the phenomenon of street children emerged in the 1920s and 1930s in Harat al-Yahud and Ard al-Yahud, the leadership of the MENA Jewish communities in Haifa argued that it was the result of neglect by the Jewish Agency (Ha-Sokhnut ha-Yehudit) and the National Council.Footnote 29 This position was manifested in a letter sent by parents of children who studied at the Beit Yitzhak elementary school (also known as Yesod Ha-Dat, “the foundation of faith”) in Harat al-Yahud to the National Council in July 1939. The letter warned that “the street children are becoming more numerous every day and crime is spreading among them. The public should know that the miserly approach of the Education Department toward these children will one bright day return to avenge the entire Yishuv.”Footnote 30

The resentment evident in these claims sparked public protests in Haifa led by the Sephardi and Maghrebi leadership in 1923, 1927, and 1937. The protests were directed against the National Council and the Jewish Community Committee (Va‛ad ha-Kehila ha-Yehudit), which were responsible for meeting social, welfare, and cultural needs within the Jewish community. A detailed discussion of this aspect is beyond the scope of this article, but it is important to note that, as part of the protest, representatives of the Sephardi and Oriental Jewish communities in Haifa temporarily withdrew from the city’s Jewish Community Committee, claiming discrimination in budgets and political representation. These protests show that even during the Mandate period there was already a protest movement in Haifa led by an elite that emerged among the Maghrebi Jews who had migrated to the city during the 19th century. This leadership was excluded from centers of power in the Zionist movement institutions and pushed to the margins of the Jewish community in Palestine.Footnote 31

In the 1940s, the phenomenon of the abandoned Jewish children in Haifa centered around Hashomer Street, which as noted bordered on Wadi Salib.Footnote 32 A census conducted in Hadar HaCarmel at the beginning of 1948 by the Desk for Attention to Abandoned Youth (Ha-Mador le-Tipul be-No‛ar he-‛Azuv) in the Social Work Department of the National Committee and the Education Department of the Jewish Community Committee identified 476 children ages six to fourteen who had dropped out of studies. Of these, 21 had never attended school, 137 had been absent from studies for more than four years, and 318 had been absent for between one and four years. The neighborhood “most afflicted by neglect” at the time was around Hashomer Street.Footnote 33 Of 1,463 Jewish families recorded in the census, 1,267 (including 2,652 children) endured in harsh living conditions in one-room apartments. The vast majority of these Jewish families lived on Hashomer Street and the streets adjoining Wadi Salib. The census also found that only 12.5 percent of children attended clubs, playgrounds, or youth movements; seventy-nine of the children in this area worked as couriers or were employed in craft shops, homes, and sewing shops.Footnote 34 This profile reflected that of the children’s parents: most of the fathers were employed in the construction industry as unskilled workers, and the mothers were employed in households.Footnote 35

The phenomenon of children who dropped out of school was particularly evident, as noted above, at Beit Yitzhak elementary school. This school was founded in Harat al-Yahud in 1934 under the name Yesod Ha-Dat, as a framework that unified several traditional elementary schools that focused on religious education (Talmudei Torah, or Torah study).Footnote 36 As will be discussed below, in the 1950s this school relocated to Samuel Ben Adaya Street, on the border between Ard al-Yahud and Wadi Salib, and was attended by hundreds of children from migrant families from North Africa, and particularly Morocco, who lived in and around Wadi Salib.

The Stairwell Generation

In the months following the battle of Haifa in April 1948, the remaining Palestinian population in the city was forced to evacuate their homes and concentrate in Wadi Nisnas.Footnote 37 Concurrently, approximately 33,000 Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe and the Middle East settled in Haifa, marking the beginning of large-scale Jewish migration to Israel.Footnote 38 Of these, approximately 15,000 were concentrated in the eastern strip extending from Wadi Salib east to Wadi Rushmiya, and some 5,000 settled in the western area, between Wadi Salib and the German Colony.Footnote 39 As in other deprived urban neighborhoods and transit camps, the migrant population was in a state of constant flux and transition, not only between different areas but between different apartments in the same neighborhood. Moves between apartments within Wadi Salib, which following the Nakba was transformed from an Arab neighborhood to a Jewish one, were regarded as “moving up in the world,” because “each street further up, that is to say closer to Mount Carmel, was more modern and had better and more comfortable apartments.”Footnote 40 The process of transition and migration within Wadi Salib continued throughout the 1950s and 1960s. During this time, Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe gradually moved out of the area to Hadar HaCarmel or into permanent accommodation in housing projects. They were replaced by Mizrahi Jews, and Moroccan Jews in particular. Jews from Poland, Romania, and Hungary sought “to leave their dilapidated homes, move their children away from the narrow alleyways, and bring them into new homes,” whereas most of the Jewish migrants from North Africa “remain as permanent residents in the poor neighborhoods.”Footnote 41

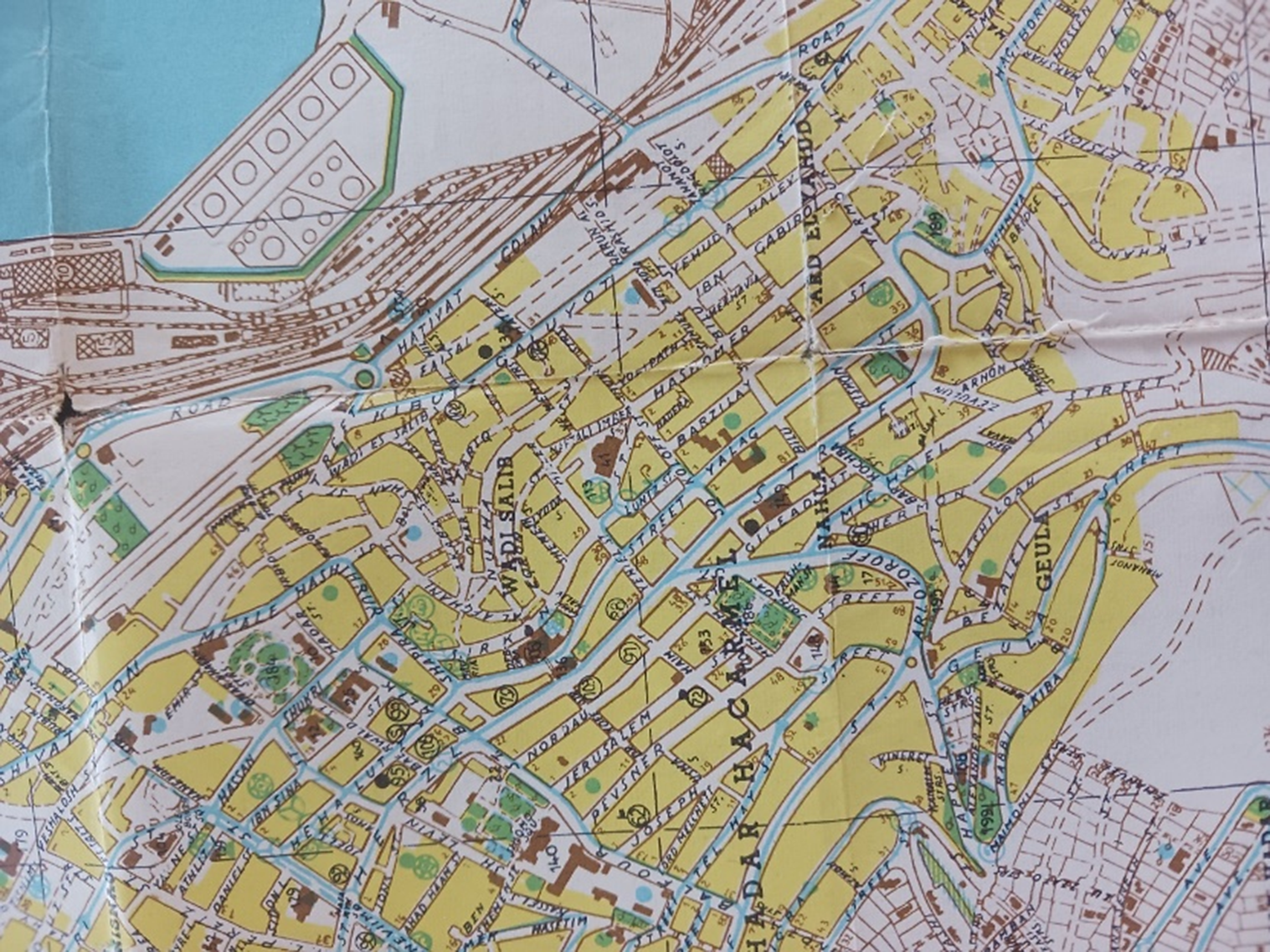

Despite the difficult living conditions and deprivation in Wadi Salib in the 1950s, the area attracted Jewish migrants from Morocco who relocated to the area from the development towns and transit camps. One of the economic factors encouraging migration to Wadi Salib was its location on the edge of the urban center of Haifa, which at the time extended from the wholesale commercial area by the port to the retail and entertainment center in Hadar HaCarmel (Fig. 2).Footnote 42 Wadi Salib’s location between the downtown and uptown sections of Haifa, between the former Arab town and the Hebrew town, and between the Mizrahi town and the Ashkenazi or Western town, also reflected the correlation between topographical location, social status, and ethnic and national identity. Haifa Deputy Mayor Zvi Barzilai expressed this correlation succinctly in 1959: “Each layer as you ascend the mountain exceeds its predecessor in both topographical and social terms.”Footnote 43 In this sense, the migrant population found itself trapped by identity and class in a neighborhood that was suspended between the Arab and Moroccan-Jewish past, embodied by downtown Haifa, and the Israeli future, embodied by Hadar HaCarmel.Footnote 44

Figure 2. Map of Wadi Salib, Hadar HaCarmel, and Ard al-Yahud. University of Haifa Map Collection, Map 2-R-Haifa-A-12-1956/1 C.2.

A further factor that drew Jewish migrants from Morocco to Wadi Salib was the dominance of this community in the neighborhood and the communal solidarity it offered. Nissim Levy, who grew up on Hashomer Street, described Wadi Salib in his memoirs as a neighborhood where Moroccan Jews “set the tone” and as an area dominated by Moroccan food, fashion, and music. “If you climbed up a little and reached Herzl Street,” Levy wrote, referring to the main road in Hadar HaCarmel, “you encountered a totally different way of life.”Footnote 45 Shmuel Sharvit, who grew up in a Moroccan-Jewish family in Wadi Salib in the 1950s and 1960s, recalled the sense he had as a child of the strong community spirit in the area, its multicultural character, the Arabic music that emitted from radios in the cafés, and the fragrances of Moroccan dishes. Charbit also recalled the attempt to preserve Moroccan-Jewish traditions in dozens of synagogues that flourished in the neighborhood. These synagogues, which served as social institutions as well as houses of prayer, operated alongside cafés, craft shops, and stores, particularly along Stanton Street.Footnote 46

The identification of the Wadi Salib neighborhood and the protests of the summer of 1959 with Moroccan Jews demonstrated not only the connection between the migration process and the formation of community identity, but also the link between Mizrahi identity and political and social protest. The existence of a Mizrahi consciousness and shared identity among Sephardi and Middle Eastern Jews was apparent even during the Mandate period. This consciousness was manifested, for example, in political and public organizations, including in Haifa, and in their self-perception of their identity as natives of the land and the East (bnei ha’aretz ve-hamizrah), culturally and historically rooted in the local and historical space, and as representatives of a Jewish-Arab hybrid identity.Footnote 47 These components also existed in the 1950s and influenced the responses to the processes of Israelization and de-Arabization that Arab Jews underwent in Israel. In this way the development of Mizrahi identity in the 1950s also was due to the existence of a shared experience of oppression and humiliation.Footnote 48 The Moroccan-Jewish experience in Wadi Salib was similar to the process that took place among migrants from MENA countries in other neighborhoods, such as Musrara in Jerusalem, and in the transit camps.Footnote 49 It expressed the consolidation of a community identity not only against the backdrop of encounters with the “other” European Jew, but also against the backdrop of encounters between the Mizrahi communities themselves, and sometimes not only between different countries of origin, but also between communities in different regions of the same country. The influence of encounters and intercommunity relations was evident in the fact that Mizrahi identity was not monolithic and underwent processes of change.Footnote 50

By the late 1950s, following the process of migration within, to, and from Wadi Salib, the neighborhood and the surrounding area had a population of some 20,000 inhabitants, one-third of whom were Jewish migrants from North Africa, mainly Morocco. The proportion of Moroccan migrants among recipients of social assistance in this area, between Wadi Salib and Wadi Rushmiya, was around fifty percent, and Moroccan Jews accounted for some eighty percent of impoverished laborers in the city.Footnote 51 The dominance of Moroccan and North African Jews in the neighborhood increased further in the 1960s following the gradual eviction and demolition program managed by the Government Municipal Company for the Rehabilitation of Housing in Haifa (Ha-Hevra ha-Memshaltit ha-‛Ironit le-Shikum Shekhunot ha-‛Oni be-Heyfa).Footnote 52 Due to this process, the population of Wadi Salib fell to 5,045 by 1967.Footnote 53

In the late 1950s, Wadi Salib covered an area of 14.5 hectares and comprised 394 houses, which were divided into 1,754 apartments containing a total of 2,862 rooms.Footnote 54 The water, drainage, and sewage systems in the neighborhood were inadequate and the average apartment size was one and a half rooms. The occupants of 1,216 apartments paid rental fees or key money to the Development Authority (Reshut ha-Pituah), which had received abandoned Palestinian property. However, the residents of 538 apartments did not have formal contracts with the Development Authority, and accordingly were referred to as “squatters.”Footnote 55 This group included several dozen young residents of the neighborhood who lived in the stairwells of buildings around the neighborhood and were known as the “stairwell generation.” To reach them, it was necessary “to proceed up and down the maze of steps and pass rows of hovels built inside each other” (Fig. 3).Footnote 56 Like the street steps in the neighborhood, these stairwell accommodations also embodied the aspiration to move from shared and temporary space on the stone steps to a permanent and private location—an apartment, or at least a room. A few days before the outbreak of the Wadi Salib protests, journalist Tzadok Eshel reported on the activities of the Union of Migrants from North Africa, which was established in early 1959 by David Ben-Harush, a native of Casablanca who had migrated to Haifa a decade earlier.Footnote 57 The distress faced by the “stairwell generation,” which was regarded by Eshel as evidence of the inability of young Moroccan Jews to integrate in Israeli society, also was manifested in the protests that erupted in Wadi Salib. On 9 July, the Union of Migrants from North Africa distributed a broadsheet entitled “Is Our Blood Cheap?” (Ha-im Damenu Hefker?). The broadsheet declared: “We see them at night looking for somewhere to sleep in the stairwells and dark cellars. During the day, like hungry wolves, they try to find a day’s hard labor to silence their hunger.”Footnote 58

Figure 3. Wadi Salib in the 1950s. From the digital collection of Younes and Soraya Nazarian Library, University of Haifa. Image attributed to Ami Yuval.

So the Arab-Jewish space of Mandate Haifa changed during the 1950s, emerging as a borderline neighborhood between downtown Haifa and the city on Mount Carmel. However, it continued to serve as a focus for foment and for social and ethnic rage. The problems of employment and housing, embodied in the phenomenon of the “stairwell generation,” were accompanied by problems concerning the education of children.

The Protest Children

Children and women played an active role in the demonstrations that took place on July 8 and 9, and particularly in the procession led by David Ben-Harush from the Rambam Synagogue to the police headquarters and in the confrontations with the police that occurred in Faysal Square on July 9. During these demonstrations, the police faced “masses of children and women, including pregnant women.”Footnote 59 During the demonstrations that resumed in Wadi Salib on July 31, again many women and children were among the demonstrators.Footnote 60 The arrest and prosecution of a teenage boy and four women who had participated in the protests strengthened the claim by Haifa Mayor Abba Khoushi that “the riots and assault were mainly led by women and children.”Footnote 61 The same argument was raised by the Etzioni Commission.

The Etzioni Commission was established by the government on July 19, 1959 to investigate the causes of the outbreak of demonstrations, determine whether they were organized, and examine the activities of the police. The commission, headed by Judge Moshe Etzioni, heard testimonies from 46 witnesses in public sessions and submitted its report to the government on August 17, 1959.Footnote 62 The report concluded that “in most instances, half of [the protestors] were children, women, and adolescents.”Footnote 63 Such descriptions highlight the active participation of children and adolescents in the protests. Moreover, they also served as strategic participants whose presence in the demonstrations emphasized that the protests were directed against the poverty they faced, as well as the position of the leaders of the protests that discrimination against Moroccan Jews was evident not only in employment and housing, but also in the elementary education system, which created gaps between the children of Wadi Salib and their peers in Hadar HaCarmel.Footnote 64

The broadsheet disseminated on July 9 expressed a sense of anger and frustration due to the gulf between the education system and living conditions provided for the children of Wadi Salib and those enjoyed by children in Hadar HaCarmel, “from the windows from which they look down on our lives and see our children barefoot and hungry.”Footnote 65 In a further broadsheet disseminated by the Union of Migrants from North Africa a few days later, Ben-Harush warned that “our community is suffering in any respect—in employment, in housing, and in education. We will not abandon our barefoot and hungry children to professional politicians.”Footnote 66 The conditions of poverty in which the neighborhood children lived and the claims concerning their neglect also were raised in the testimonies presented to the Etzioni Commission. During the hearings, David Ben-Harush emphasized that the education of the community’s children was one of the factors behind the eruption of the protests. In his testimony before the commission, Moshe Gabbai, a native of Casablanca who participated in the protests, described his feelings when he walked up to Hadar HaCarmel: “In the morning I see the children—well-dressed, wearing shoes, with schoolbags on their backs—and my heart aches. Will my child ever enjoy these conditions, or will he grow up in the filth of Wadi Salib?”Footnote 67

The protestors’ anger and frustration were directed not only at the emblems of the government and the Histadrut, but also at the residents of Hadar HaCarmel and Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe who lived in Wadi Salib.Footnote 68 For example, Rina Frank Mitrani, who grew up in a family of Romanian origin that lived on Stanton Street, recalled in her memoirs that the Ashkenazi residents of the neighborhood closed themselves up in their homes during the demonstrations as the protestors damaged property in Hadar HaCarmel and destroyed the Mapai and Histadrut clubs. Commenting on the outbreak of ethnic and socioeconomic tension, Haifa Deputy Mayor Zvi Barzilai described the relations between Wadi Salib and Hadar HaCarmel. The residents of Wadi Salib, he suggested, “see the lights of Hadar HaCarmel above them while they are trapped between unemployment, the dark, moldy alleys, and urban congestion.”Footnote 69 The contrast between the well-lit streets of Hadar HaCarmel, which symbolized enlightenment and modernization, and the dark alleys of Wadi Salib, representing ignorance and the premodern era, were embodied in the image of the demonstrators “ascending to Hadar HaCarmel from the depths of downtown Haifa.”Footnote 70 This motif highlights the perception of the Moroccan Jews by the absorbing establishment as a threat not only to public order but also to the Zionist principle of the “mixing of the exiles” and to the Western and modern character of the State of Israel.Footnote 71

The perceived threat posed by the world at the bottom of the steps and the attempt to delegitimize the protests were manifested in a broadsheet disseminated by Mapai in August 1959. The broadsheet exposed the political tension that existed between the Union of Migrants from North Africa and Mapai as the ruling party, whose control over the Haifa Workers Council and the Haifa Municipality gave the city the nickname “Red Haifa.” The leadership of Mapai and the Haifa Workers Council, who failed in their efforts to recruit David Ben-Harush to their ranks, perceived the Union of Migrants from North Africa as a political threat and accordingly claimed that the protest had received support from the opposition Herut party.Footnote 72 Entitled “On the Mount and on the Wadi,” the broadsheet sought to apply a distinction between the majority of Jewish migrants from Morocco, “who climb the mount, hold on, and set down roots in a life of labor in the Land” and the protestors, who were described as “rolling down to the wadi, on a slope of rioting and violence.”Footnote 73 In contrast, the author Moshe Shamir, who was a member of the Hashomer Hatzair movement, inspired by the war in Algeria, portrayed the Wadi Salib events as a manifestation of the tensions between “the hungry and the sated, yes. The roofless and the villa-dwellers, yes. The enslaved and the enslavers, yes. Africa versus Europe, yes.”Footnote 74

The portrayal of the demonstrations as a social and cultural threat contributed to the association of downtown Haifa with the underworld and crime. The men who participated in the protests were described as criminals and rioters, the children as bored and indolent during the summer vacation, and the women as prostitutes.Footnote 75 The attempt to delegitimize the protestors was particularly apparent regarding women, who were very active in the demonstrations. Women, some of whom worked in prostitution, encouraged men to join the protests, prevented the removal of broadsheets posted on the streets of the neighborhood, and led groups of children who threw stones at the police.Footnote 76 The portrayal of these women as prostitutes, as mentioned in several testimonies presented to the Etzioni Commission and in newspaper articles, sought to strengthen the claim that the protests were led by criminal elements. The women were accused of crossing not only legal boundaries, but also those of morality.Footnote 77

The involvement of women, however, reflected the strength of the events as a protest that was not only ethnic, but also had a class and gender dimension. Research into Mizrahi feminism usually begins with activities that emerged during the 1970s and pays less attention to the activities of Mizrahi women in the migrant moshavim, transit camps, and in impoverished neighborhoods of the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 78 The involvement of women and children in the Wadi Salib protest, which may be described as a form of maternalistic politics, also was evident when women carrying their babies gathered outside Haifa Magistrate’s Court, where detained protesters were brought for trial. Another example was the demonstrative and provocative action taken by Esther Amar, who lived on Omar ibn al-Khattab Street and gave testimony on behalf of the defense in the trial of the Wadi Salib detainees. Amar left her baby at the entrance of the police station in protest at her husband’s arrest in the demonstrations.Footnote 79 In contrast to the prevailing view among medical and social professionals in the 1950s that Mizrahi women tended to be passive and showed defective mothering skills, such actions by women are evidence of political activism and a social campaign in support of their children’s rights.Footnote 80

Borderline Children

In August 1959, the Haifa Municipality established a municipal committee to examine the problems in Wadi Salib.Footnote 81 The committee focused on efforts to find solutions for the housing problem. Regarding education, it recommended the rehabilitation of children defined as “degenerated” (menuvanim).This term was applied to children who suffered from learning difficulties and as a result dropped out of studies or descended into crime. Mordechai Berachiyahu, who was one of the most prominent figures in the field of hygiene during the Mandate period and who founded and headed the Hygiene Department (Mahleket ha-Higyena) of the Hadassah schools, described “borderline” (gevuliyim) children in 1944 as an intermediate stratum of the educational level, between “normal” (normaliyim) and “abnormal” (lo normaliyim) children and between “average” (benoniyim) and “enfeebled” (refuyey sekhel) children.Footnote 82 However, Berachiyahu noted the connection between the conditions of poverty in which the children lived and their educational level. His analysis was based on data from elementary schools in Haifa, where Mizrahi children living in and around Wadi Salib were prominent among those defined as “borderline children” (yeladim gvuliyim).

Although children who faced difficulties in their studies were termed “borderline” in the 1940s, by the 1960s they were referred to as “requiring nurturing” (te‛uney tipuah) or “backward” (nehshalim) (Fig. 4). The educational difficulties these children faced intensified the phenomenon of dropping out. Despite the Compulsory Education Law (Hok Hinukh Hova), it was estimated in the late 1950s that approximately five percent of all elementary school students had dropped out of their studies. Many of these dropouts were children of Jewish migrants from MENA countries. In Haifa as a whole, five percent of students were found to be facing educational difficulties and to require special education, whereas the proportion in and around Wadi Salib was around fourteen percent.Footnote 83

Figure 4. Wadi Salib, 1950s. Photograph by Amiram Erev, Shikun and Binui Archives.

Another cause for dropping out, as during the Mandate period, was that some children found employment to help their families make a living, and others helped maintain their own family’s home. One such child was Jacqueline Revivo, a thirteen-year-old girl who was interviewed by Hannah Stern, a correspondent for the Communist Party newspaper Kol Ha‛am (Voice of the People). Jaqueline had never attended school and was illiterate. She lived with her family in a one-room apartment in Wadi Salib and cared for her four brothers.Footnote 84 Among the children detained at the demonstrations in Wadi Salib, many had dropped out of school and were helping their families earn a livelihood.Footnote 85 The inability of children in the neighborhood to complete their homework or receive extra lessons, and the discrepancy between the students’ age and their level of studies, also contributed to the phenomenon of dropping out.Footnote 86

The connection between social distress, life in deprived neighborhoods, and educational difficulties among migrant children from Arab countries was discussed extensively in the 1950s and 1960s. Researchers from the fields of public health, social work, and education, who came into contact with the children of Wadi Salib in the course of their professional roles, often approached this topic from a modernization theory perspective. An example of this approach is a study undertaken in 1961 by Isser Yachnin, the physician at Beit Yitzhak State Religious School. As mentioned, until the late 1930s Beit Yitzhak had been located in Harat al-Yahud and was originally established as Yesod Ha-Dat, through the unification of several Talmudei Torah. By the 1950s, the school was situated on the outskirts of Wadi Salib. It was larger than the two religious elementary schools of Agudat Israel and the two schools of the state that operated around Wadi Salib, and had 627 students. In his study, Yachnin analyzed the demographic profile of 118 families (969 individuals) of second-grade students at the school. He described the children as “very neglected in terms of bodily cleanliness and clothing and chronically infested with lice.” The children’s lives were particularly hard in winter due to the lack of hot water for bathing.Footnote 87 The children also were malnourished, and accordingly around forty percent of the second-graders ate at the school canteen. In his study, published in the journal Briut ha-Tsibur (Public Health), Yachnin noted that the most prominent health-related finding was that one child in six had defective posture due to the incongruence between the children’s height and the furniture in their homes.Footnote 88

Yachnin’s study was consistent with the research approach at the time among medical professionals in the field of public health and the belief that hygiene and sanitation and the infrastructure in slum neighborhoods had an impact on children’s educational abilities.Footnote 89 Accordingly, his study also examined the living conditions in Wadi Salib. The apartments in which the students lived had an average size of 1.8 rooms, and the average number of people living in each apartment was 8.2. Approximately half the apartments suffered from dampness. On average, 1.5 children slept in each bed, and thirty percent of the children wet their bed at night. Yachnin noted that very few of the homes had a special corner for the children, and the families had an average of six children. Accordingly, “preparing homework in these conditions and in such congestion was virtually impossible.” The result was that approximately half the second-graders had difficulty reading and one-fourth of them were behind in their level of studies. The children of Wadi Salib were perceived as living not only in poor hygienic conditions inconsistent with modern and Western living patterns, but also, in a family and domestic setting, lacking in furniture regarded as civilized and Western, which was incompatible with the Israeli bourgeois model.Footnote 90 The division between the top and bottom of the street steps was regarded by the professional and educational figures who attended to the children of the neighborhood as a metaphor for the contrast between low and high cultural standards.

Yachnin also examined the parents’ level of education and employment profiles, based on his assumption that there was an affinity between parents’ education and socioeconomic position and their children’s educational success. Regarding the mothers, he concluded that “the overall picture of women’s lives in Wadi Salib is rather sad.” Women got married at a very young age (15.5 years on average); seventy-three percent of them were illiterate and seventeen percent were employed outside the home, mainly in domestic work.Footnote 91 The employment of Mizrahi women as domestic assistants in the neighborhoods on Mount Carmel also illustrated the ethnic and socioeconomic gulf between Wadi Salib and Hadar HaCarmel. Moreover, the women’s work created an arena for an encounter with middle-class women who lived at the top of the street steps, highlighting the character of Wadi Salib as an in-between space. As for the fathers, ninety-seven percent were of North African origin, mainly from Morocco. Yachnin described them as caught in a constant struggle for survival; eighty percent of them were unskilled laborers.

Moshe Rabi, principal of Beit Yitzhak school, also noted the impact of the living conditions in Wadi Salib on the children’s studies. In a memorandum he wrote in 1961 on the children of the neighborhood, Rabi—who also was one of the leaders of the Sephardi community in Haifa, and whose views were typical of those of the community—described Haifa as a city divided into three levels: the downtown area, Hadar HaCarmel, and Mount Carmel. Rabi portrayed Hadar HaCarmel as a garden neighborhood with large homes and well-lit streets where children enjoyed libraries and music lessons and “walk around clean and cheerful, full of the joy of life.” Wadi Salib, in contrast, was described as a “miserable ghetto” that had no gardens or lawns. As one walked down the steps to the downtown area, Rabi noted, “it is as if you are descending into a different world.”Footnote 92 Rabi described the physical character of Wadi Salib as a collection of dense homes packed alongside and on top of each other, along and between the street steps. Some of the street steps led to shared courtyards, whereas others opened into streets. Rabi claimed that the children of Wadi Salib were aware of the difference between their condition and that of children in Hadar HaCarmel. To this day, this experience remains etched in the memories of those who grew up in Wadi Salib, as was exemplified in my interviews with Shmuel Sharvit, Daniel Bar-Eli Bitton, and Shimon Cohen, who grew up in the area in the 1950s and 1960s in families of Moroccan origin. They recalled their frequent visits as children to the Borochov Library and their encounter with homes with pianos and other musical instruments in Hadar HaCarmel.Footnote 93

Forbidden Games

In her book, Leah Birnbaum, who worked as a teacher in one of the schools in the Wadi Salib area, described the presence of “an invisible wall, a wall of alienation and prejudice” between Wadi Salib and Hadar HaCarmel.Footnote 94 Birnbaum described several examples of children who managed to overcome this invisible wall and “to emerge from dependence and backwardness into independence.”Footnote 95 However, the children of Wadi Salib crossed this barrier between Wadi Salib, the port area, and downtown Haifa and Hadar HaCarmel and the upper city on a temporary and daily basis. In this context, the street steps served as a passage and a liminal area allowing them to cross the invisible wall. The streets of steps that led to this “border” and connected the stone houses and courtyards in the neighborhood served as a refuge and a playground for the children of Wadi Salib. Daniel Bar-Eli Bitton recalled the children running wildly and repeatedly up and down the steps.Footnote 96 Whereas the bottom of the steps drew the children toward a forgotten and deleted Arab and Moroccan past and toward the multicultural and crime-ridden port area, their top symbolized the aspiration to advance toward integration in Israeli society and to change their living conditions and class. The steps and streets were the kingdom of the children, who like their parents were restless and constantly in motion.Footnote 97 As they left the crowded homes and courtyards, the street steps and alleys served as a corridor for the children. The winding alleys and the maze-like clusters of homes, which to an outsider seemed to lack any organizing structure or logic, were not frightening to the children, but familiar and known. The step streets, free of vehicles, offered a safe open space where they could escape from the overcrowded and stifling rooms in their homes.Footnote 98

The children’s vagrancy, which tended to focus around the wholesale market by the port and the retail and entertainment area in Hadar HaCarmel, was in part the result of the format of studies in the local schools. In Beit Yitzhak and some of the other schools, studies took place in two shifts, so that children attending the later shift were left without any structured activity in the mornings.Footnote 99 Recognizing that the children’s educational achievements were influenced not only by their parents’ deprivation and their living conditions, but also by the conditions in the schools, the parents’ committee at Beit Yitzhak demanded in 1957 that Haifa Municipality abolish the second shift of studies; they emphasized that “these children do not have the same conditions as the children in Hadar HaCarmel or on Mount Carmel.”Footnote 100 The children’s vagrancy was the product not only of their harsh living conditions and the lack of playgrounds, libraries, or clubs, but also of deficiencies in the local education system. Their wanderings enabled them to encounter the economic and social gulf between the green gardens of Hadar HaCarmel and the gray landscapes of Wadi Salib; between the Arab stone houses in their neighborhood and the white city further up the mountain; and between the dark, narrow alleyways and the broad, well-lit streets. As they moved between the two worlds, they developed the sense of living in a transitional and liminal area. Their vagrancy challenged the dichotomy between uptown and downtown, east and west, and Jews and Arabs, creating arenas for encounters and for play—for example, between the Jewish children and the Arab children who lived on the outskirts of the neighborhood.Footnote 101

A thirteen-year-old boy described this daily experience of vagrancy and exploration: “We leave our homes in the morning, telling our parents that we’re going to school. But instead we go up to Hadar or down to the port and watch the stores and people.”Footnote 102 The children were often described as “small, barefoot or wearing torn shoes without socks, badly dressed, dirty, and neglected.”Footnote 103 Their presence on the streets served as a constant reminder of the social, economic, and ethnic gulf between Wadi Salib and Hadar HaCarmel. The municipality constructed a small playground on Hashomer Street, but within Wadi Salib there were no play areas similar to those that had operated in the area during the Mandate period in cooperation with the Guggenheimer Foundation.Footnote 104 The children’s main pastime was visiting the movie theater. Whereas the adults of Wadi Salib met in the synagogues and cafés, the cinemas—and particularly Hadar Cinema on the outskirts of Wadi Salib (Fig. 5)—became the children’s chief refuge. Yachnin’s study found that forty percent of the second graders at Beit Yitzhak school went to the movie theater around three times a month.Footnote 105 The theater actor Rami Danon, who was born in Fes, Morocco, and grew up in Wadi Salib, described the significance of these visits, positioning the movie theater as a form of escape from physical and psychological hardship.Footnote 106 Another favored venue was Talpiot Market, adjacent to Wadi Salib: “Gangs of children wandered through the market, sometimes helping peddlers for a few pennies, sometimes pinching whatever they could.”Footnote 107 Situated between Wadi Salib and the main roads of Hadar HaCarmel, Talpiot Market served as an arena for cultural and ethnic encounter as well as providing a livelihood for residents of Wadi Salib, who worked as peddlers or porters; children also were employed in unloading merchandise from trucks.Footnote 108

Figure 5. On the right is the abandoned Hadar Cinema. The cinema is located on Kibbutz Galuyot Street (formerly Iraq Street), which connects Wadi Salib to Ard al-Yahud. At the left edge of the photograph, a new residential project at the corner of Wadi Salib and Omar ibn al-Khattab Streets illustrates the change that the neighborhood is undergoing. Photograph by the author, 2024.

The vagrancy described here was regarded as a classic symptom of neglect and was categorized as an offense.Footnote 109 In 1953, for example, vagrancy accounted for six percent of offenses leading to the prosecution of children and youths.Footnote 110 However, alongside vagrancy motivated by the need for entertainment or employment, children also were involved in more serious offenses. In 1953, the justice minister appointed a committee to examine the phenomenon of delinquency among youth in Israel. The committee’s report, completed in 1956, found that around half the children arrested by the police were suspected of property offenses and were ages nine to fourteen; eighty-four percent of children prosecuted were Mizrahim.Footnote 111 The committee, whose members included Karl Frankstein, the head of the Szold Institute for Children and Youth and a professor of education at the Hebrew University, concluded that processes of modernization were responsible for this phenomenon and for ethnic gaps in education.Footnote 112 The committee attributed the descent of children and youth into crime to poor economic conditions, negative influences in the home, a lack of correlation between educational services and children’s needs, and psychological or intellectual defects at the individual level. Additionally, in keeping with prevailing attitudes in the behavioral sciences at the time regarding Mizrahim, the committee found that “profound contrasts between the civilization of the country of origin and that of the country of migration” created an acute confrontation between opposing cultures.Footnote 113 This, in turn, led to “the inability of the young person to adapt to modern civilization, with its tensions and prohibitions.”Footnote 114 Against the backdrop of these discussions, and as a result of the Wadi Salib protest, the Youth Law (Care and Supervision) was enacted in July 1960. The law was intended to ensure supervision and oversight of children and youth who threatened the social and political order, and was a response to the phenomenon of vagrancy, children engaged in peddling, and those suspected of criminal activities.Footnote 115

Despite the dominance of the modernization theory in behavioral sciences at the time, truancy officers in Haifa suggested that one of the causes of delinquency among minors was the contrast between downtown Haifa and the neighborhoods on Mount Carmel, which encouraged a sense of discrimination, injustice, and mistrust in the establishment.Footnote 116 In 1959, 724 offenses were recorded in Haifa involving minors over the age of nine; by 1962 this figure had risen to 1,630.Footnote 117 Most of the offenses involving children—some as young as seven or eight—were property related. Hannah Stern, the Haifa correspondent for the newspaper Kol ha-‛Am, used the term “forbidden games” (mis’hakim asurim) to refer to the organized gangs of children who undermined public order in Hadar HaCarmel. In most cases, she explained, the children stole fruit and vegetables from the markets around Wadi Salib and sold them to passers-by or customers in cafés. The children used the proceeds to purchase candy at kiosks, products from sports shops, and movie theater tickets.Footnote 118 Like the demonstrators who broke out from the confines of Wadi Salib in the summer of 1959, therefore, these children continued in the 1960s to challenge the cultural and social barriers that constricted their families and the inability of most of their parents to extract themselves from the liminal zone in which they lived and ascend the street steps to Hadar HaCarmel.

Conclusion

The perception of the Wadi Salib events as a turning point in interethnic and intercommunal relations in the State of Israel is reflected in the manner in which these events became a litmus test and measure of comparison for subsequent protests among migrants from Arab and Muslim countries. Examples of this include the demonstration held on 7 August 1960, in front of the Jewish Agency offices in Tel Aviv, by hundreds of Jewish migrants from Iran who lived in the Amishav transit camp, demanding their evacuation from the transit camp and provision of housing, and the turbulent demonstrations that erupted in the Hatikvah neighborhood on September 22, 1961, following the demolition of an illegal building.Footnote 119 The impact of the Wadi Salib events also was reflected in the creation of the position of the prime minister’s adviser on the integration of Jewish migrants from the Middle East and North Africa, as well as in reforms of the education system and the enactment of the Child Benefit Law. These reforms reflected the understanding that integration in Israeli society required an improvement in the living conditions of the MENA Jewish migrants, most of whom had a relatively large number of children, as well as recognition of the need to improve the education system and adapt it to meet the needs of the children of Mizrahi migrants, among others.

The connections between protest and space and between protest and children were already apparent during the British Mandate period in and around Wadi Salib, a shared Jewish-Arab domain. The eastern area of Haifa, which included several mixed neighborhoods, was already a center for protest by Jews of Middle Eastern and North African origin during the Mandate period, including on the issue of children who had dropped out of the education system. This issue of persistent poverty and educational problems among children, as well as the fact that the protests in Haifa in the 1920s and 1930s were led by Maghrebi Jewish leadership, allows for the presentation of a long Mizrahi historical perspective, creating a connection between Mizrahi protests and distress during the Mandate period and the 1950s.

Throughout the 1950s and thereafter, the area remained a focus of poverty and deprivation. However, the spatial change that occurred in and around Wadi Salib after the 1948 war and the Palestinian Nakba, and the transformation of Wadi Salib into a Jewish migrant neighborhood, created a gap between the area and the Hadar HaCarmel neighborhood. The geographical location of Wadi Salib between downtown Haifa and Hadar HaCarmel mirrored its character as a liminal space between cultures, identities, and communities. The street steps of Wadi Salib and the phenomenon of the “stairwell generation” manifested the ethnic, economic, and social gulf between two neighborhoods, including the prevalence of deprivation among the children of Wadi Salib. The relations between the top and bottom of the street steps illustrated this socioeconomic gulf between the different parts of Haifa and the inability of the Moroccan Jews in Wadi Salib to escape the confines of their neighborhood and improve their socioeconomic condition. The gulf in relations between the neighborhoods also was evident in the field of education, as evidenced by the active involvement of children in the protests of the summer of 1959. Indeed, education was one of the main issues that sparked eruption of the protests.

Over recent years, several reunions have taken place in Haifa, bringing together some of those who grew up as children in Wadi Salib in the 1950s and 1960s. At these encounters, such as the “Wadi Salib Stories” project, participants have expressed nostalgia for the community life and solidarity that characterized their childhood in the neighborhood. The encounters emphasized not only the poverty and deprivation of their childhood, but also the experience of growing up in an open and liminal zone that encouraged an encounter between communities and cultures. Significant place also was devoted in the childhood memories to the children’s vagrancy for the purposes of entertainment, employment, and delinquency. These recent reunions form part of the attempt to preserve the memory of the neighborhood, which is currently undergoing change through processes of rehabilitation, renovation, and conservation. After the Arab inhabitants of Wadi Salib became refugees, and following the displacement of the Jewish migrants who settled in the area, Wadi Salib has in recent years entered a new stage of spatial change. However, the neighborhood streets, with their dilapidated and sealed-off stone homes, still remain, bearing silent witness to the Arab and Jewish history of this area and to the protesters who, in the summer of 1959, erupted forcefully from the stairwells and street steps in ethnic, social, gender, and generational protest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my research assistants, Stephanie Colley and Nadav Ganon, for their valuable assistance with this research. This study was partially written during my sabbatical in the Jewish Studies program at Dartmouth College, and I also want to thank Professor Susannah Heschel and the center’s staff for their support during my stay at Dartmouth. This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation [Grant number 808/22].