On the stroke of midnight, 15 August 1947, V. K. Krishna Menon stood in the India League Office at 165 Strand as a solemn rendition of the Jana Gana Mana rang out and the first Indian tricolour was unfurled in London.Footnote 1 After twenty-eight years in England striving for independence – and at the point of victory – Menon stood on the very same spot from which he had campaigned for it for all those years. Soon to become known as the ‘second most powerful man in India’, after his friend and ally Jawaharlal Nehru, Menon was already considered a fractious and determined character by friend and foe alike.Footnote 2 Referred to as ‘Mephistopheles in a Saville Row suit’, ‘India's Rasputin’, and even ‘Nehru's evil genius’, Menon was and still is seen as a contentious figure.Footnote 3 There is no doubt, however, about his impact on the Indian independence movement in Britain, as well as his later influence in India where his friendship with Nehru contributed to a turbulent political career.Footnote 4 Menon was appointed India's first high commissioner to the United Kingdom with India's independence in 1947, and later held posts as defence minister and India's delegate to the United Nations, wielding significant influence in India post-1947.Footnote 5 To understand Menon's position in independent India, historians have sought to define his political thought. This is often short-handed as socialist, drawing from his links to the Communist Party, agreement with Soviet policy, and his role in Nehru's cabinet as chief ideological architect of foreign policy.Footnote 6 However, both Menon and his political thought are far more nuanced than past histories have suggested. In arguing for a reassessment of his political thought, this article posits that it was his time in England, which spanned from 1924 to 1952, that was key to the development of Menon's early political and personal views. Furthermore, it argues that an assessment of his life in Britain is best understood by critically engaging with his short-lived yet highly impactful publishing career.

The majority of historiography upon Menon falls into two categories. The first contains accounts heavily critical of his role in government, citing him as divisive and a liability. These works note his close friendship with Nehru as the reason Menon continued in his roles despite significant opposition, noting that the two became close during his time in England although largely brushing over the rest of Menon's activities in this period.Footnote 7 The opposite are histories written with excessive reverence, owing to the negativity of the former texts as well the fact that several were written by close associates or family relations.Footnote 8 These focus on Menon's tireless campaign for independence, often giving personal insight into his own ascetic crusade. What is largely agreed upon, however, by critics, admirers, and those in between, is Menon's political thought. It is typically described as ‘socialist’ with occasional links to his youthful Theosophic tendencies.Footnote 9 This skews Menon's thought into a broad categorization, casting him within a number of Indian socialists at the time and, in doing so, overlooks much of the work he accomplished and the driving forces behind it. Often, Menon's politics are seen less in the realm of political thought and more as political action. This is an important distinction as many studies operate upon tested lines that the two operate in specific and separate ways. This article does not separate them, and follows the example that Shruti Kapila recently laid out in ‘converting’ Mahatma Gandhi, Muhammad Iqbal, B. R. Ambedkar, and others, from political actors into political thinkers.Footnote 10 This article seeks to ‘convert’ Menon's political actions into representations and expressions of his political thought.

I suggest that Menon's political thought was more nuanced than simply socialist, that this nuance was created during his years in Britain before independence, and that Menon's political actions in Britain can be split into three interconnected strands that often intertwined with one another. Like Kapila, I posit that it is by assessing these actions that Menon's political thought can be drawn out. Just as Kapila and Faisal Devji argued of the Bhagavad Gita, this was ‘political thought in action’.Footnote 11 The first of these strands is Menon's transformation of the British-based independence movement as secretary of the India League, where he moved the group away from Annie Besant's pedestrian and polite movement towards a more radical and effective vehicle for change.Footnote 12 Second is his time working for and within the Labour party, both as a member during his tenure as councillor, as well as the frequent engagements he had with key figures on the left, such as those associated with the British Left and other anti-colonial activists. These include links to the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), the League Against Imperialism (LAI) and the Independent Labour Party (ILP). The third strand is his publishing career, during which he worked for three major houses, often weaving in aspects from his work for the League as well as his associations with the British Left.

This article seeks to bring these threads together, utilizing Menon's publishing career as the common denominator that connects various aspects of his activism and thought. In unpacking these three strands of Menon's political action during his time in Britain, this article builds upon works that are recasting Indian political thought such as those of Kapila and Devji, as well as the work of Christopher Bayly, Kris Manjapra and Ian Hall.Footnote 13 It also draws heavily on recent works that seek to characterize the politics of the interwar period and the internationalist moment of the 1930s. The work of Michele Louro and Mark Reeves form a basis for engaging with the politics of the period, which they argue were fluid and open rather than operating as exclusive schools of thought.Footnote 14 As Louro posits of Nehru, his politics were a ‘blend’ of various influences, ones whose differences were often overlooked in this internationalist moment.Footnote 15 This article similarly sees Menon's politics as a ‘blend’, or, as Reeves notes of Menon's various political connections, ‘a web far more than a network’.Footnote 16 It is this blend, this web, that I seek to untangle.

To draw out the links between Menon's publishing career and his involvement in the Indian League and the British Left, I utilize a book history approach. As outlined in Robert Darnton's influential 1982 article, book history looks at written works not just for their content but the wider aspects relating to their publication.Footnote 17 This ranges from the author, the process of authorship, and printing, to editing, publishing, and reception. Tapping into these often complex processes, what Darnton terms a ‘communications circuit’, and taking texts on their own terms, teases out underlying motives and ideas.Footnote 18 The majority of book histories centre on the early modern, particularly the relationship between the creation of early print cultures and manuscript production. However, recently book history has begun to expand into the study of empire in the works of Antoinette Burton, Amelia Bonea, Carol Polsgrove, and most notably Isabel Hofmeyr.Footnote 19 Hofmeyr's Gandhi's printing press is an important work that recasts Gandhi and his seminal Hind Swaraj, linking his writing and publishing with his political action and thought. This article seeks to continue this trend, bringing book history to the study of twentieth-century empire and anti-colonialism.

Structurally, this article is split into two sections. The first focuses on Menon's publishing career and covers roughly ten years spanning his time from student at the London School of Economics (LSE) to his departure from Pelican Books. During this period, Menon's publishing career began, first with Selwyn & Blount (S&B) and then the Bodley Head (TBH), both prefacing the momentous Pelican Books. Over these years, Menon also aligned himself with the members on the left of British politics, developing an increasing number of connections with groups from the LAI and ILP to some members of the CPGB.Footnote 20 Similarly, his most significant political action of this period – the transformation of the India League – engaged both with and for his other contemporary endeavours. For example, lobbying Labour MPs on behalf of the League or selecting which books the big publishing houses would print linked his three enterprises. This section brings these three threads of political action together, assessing Menon's employment at three publishing houses, linking this to his increasing presence within leftist movements, and setting this against the backdrop of a resurrected India League. The second section centres on the India League book, Condition of India, released in 1933.Footnote 21 Condition is often seen as the high-point of the League yet detailed analysis of it and what contributed to it are lacking. This article assesses Condition upon the premise that Menon's role as editor is crucial to understanding the book itself, as well as how editorial choices and the construction of the book speak to his political thought. The book is emblematic of his politics at the time, and sits in the middle of Menon's publishing career when he was engaging with the three strands of his political action on a daily basis. Study of it highlights the ways in which Menon's varied and nuanced political influences manifested themselves as political action and thought.

Overall, this article argues for a reassessment of Menon's political thought, both in how we describe it but also how we view it vis-à-vis its shaping via political action. Engaging with this through a book history approach highlights the interconnected nature of Menon's time in England, and points to the rich history of the development of his politics that would become so divisive and debated in the years that followed. There has been much written about Menon's cutting political retorts, erratic sleeping habits and diet, and personal asceticism (bar a taste for expensive suits), and significantly less upon what underlined these surface-level facts. This article seeks to move beyond these reflections and get to the heart of Menon's political action and thought.

I

Menon began his editing work in London following an intense period of academic study. Arriving in 1924 upon Annie Besant's initial offer to teach short term at St Christopher in Letchworth, he instead stayed for a further twenty-eight years.Footnote 22 After teaching for a year, Menon relocated to what would become his home for the next two decades, the then-rundown St Pancras Borough of London. He quickly began his education at the LSE, as well as continuing his previous law studies in an attempt to placate his increasingly disappointed father.Footnote 23 It was at the LSE that he would meet possibly the greatest personal influence on his political thinking whilst in England, Professor Harold J. Laski; who is famously quoted as saying ‘Krishna Menon is the best student I ever had.’Footnote 24 Lecturing in political science, Laski's own politics were in line with Marxist and Fabian ideals which he interpreted into a kind of neo-Marxism. Initially promoting a form of pluralism, Laski's political thought gave way to a tempered Marxist one during his time at the LSE.Footnote 25 Noted for having an impact upon a range of future leaders of decolonized nations such as Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, and Jawaharlal Nehru, he also taught figures such as Ralph Miliband and Franz Neumann.Footnote 26

Historically, the relationship between Laski and Menon has been viewed as a one-way exchange; the latter a diligent and awestruck student, the former a messianic genius who moulded the young man from Kerala with ease. A brief overview of the secondary literature confirms this; V. K. Madhavan Kutty and Emil Lengyel both stress the importance of Laski. Lengyel posits ‘no Englishman – or scholar – ever made a greater impression on Krishna Menon’, whilst Kutty notes there was ‘a kind of osmosis between the two minds’.Footnote 27 Similarly, S. R. Bakshi and Narendra Goyal both describe the relationship as Menon coming ‘under the spell’ of Laski, and that Laski took over from Besant in Menon's mind.Footnote 28 Hall also supports this in his analysis of Menon, stating Laski's political thought wholly influenced his student.Footnote 29 I argue that the relationship between Laski and Menon was more complex and operated in both directions, whilst still emphasizing the significant impact Laski had on Menon both politically and personally.

In providing not just an ideological framework, but also the contacts and support required to turn abstract notions into real action, Menon's relationship with Laski proved foundational for his editorial career. This functioned in three distinct ways. First, was the change in Menon's political thought fostered by Laski. Before studying at the LSE, Menon's core beliefs were grounded in Helena Blavatsky's Theosophy. This was furthered due to his early ties with Besant, who was a strong proponent of Theosophy and had extended the invitation to teach at a Theosophist school.Footnote 30 However, as his time in England went by, Menon’s appreciation of Theosophy dwindled in a similar fashion to his personal relationship with Besant. In the end, Menon's transformation of the League into a more radical vehicle, promoting full independence, came at the cost of their personal friendship.Footnote 31 His adherence to Theosophy tracks this decline and, coinciding with studying at the LSE, these spiritual notions gave way to Laski's Marxist ideals. In turn, Menon internalized these into both a form of Laskian neo-Marxism, and aspects of scientific socialism.Footnote 32 Menon's abandonment of Theosophy was expressed in the direction he took the League, as the organization that was previously somewhat guided by Besant's leanings came to be supported by Menon's new leftist contacts.Footnote 33 The engagement of thinkers and members of the ILP, LAI, and CPGB, such as Ellen Wilkinson, Reginald Bridgeman, and Laski, at League events and meetings echoed Menon's developing network.Footnote 34 If we take Menon's political actions at the time of Laski's influence, an increasing leftist network and relationship with Marxist and neo-Marxist thinkers, as expressive of political thought, the trend is clear.

The second main impact Laski had upon Menon's publishing career was the contacts that he introduced his student to. Mainly members of the Labour party and ILP, the host of thinkers, politicians, and writers that Laski acquainted Menon with were to be valuable connections in the years to follow.Footnote 35 These contacts would form the basis of Menon's preferred authors when publishing series, and endowed his works, both at publishing houses and for the India League, with valuable legitimacy, as well as a distinctly leftist bias.Footnote 36 Laski's introductions were also important in developing Menon's relationship with the Labour party as an organization.Footnote 37 This was crucial to Menon's future role within the party but also in his efforts to raise awareness of the independence movement and push for institutional change. This in turn came to impact Menon's editorial work as he played literary patron to his new contacts in a relationship that benefited all involved. Third is that the Laski–Menon relationship kickstarted Menon's publishing career through finding his first post within the publishing world.Footnote 38 LSE contacts forged through his relationship with Laski opened up the opportunity for Menon to gain his first editorial role at Selwyn & Blount.

Laski was also increasingly brought into the independence campaign, first by attending meetings and later speaking at them. In a similar way that Menon was able to engage with those on the left in a unique way due to Laski's introductions, the same was true of Laski's involvement with the League. Lending his name for legitimacy and his words for their intellectual merit, Laski's contributions to the League grew when writing for Menon's cause. For example, with the inclusion of an article in the League's periodical India To-Day in 1936, Laski was featured on the cover alongside other high-profile names.Footnote 39 These included Reginald Reynolds, the left-wing ILP pacifist and long-time supporter of Gandhi; women's suffrage activist and Labour MP Ellen Wilkinson who had strong links with the CPGB; and Aldous Huxley, famed pacifist author of the dystopian Brave new world. In the same year, Laski wrote a preface in a pamphlet published by the India League.Footnote 40 Featuring speeches and writings from Gandhi, Nehru, and Menon, Laski was the only Englishman in the pamphlet. The very fact that Laski would be a name in a pamphlet entitled India speaks makes it clear how politically and personally aligned he and Menon were.

In this foreword, Laski's own politics shine through, as Menon utilized Laski's political legitimacy which was then brought in line as a reflection of the League's, and Menon's specifically, own political thought. For example, in his linkage between sentiment against British rule in India and that which ‘Russian liberals and socialists felt for the Czarist tyranny’, Laski paints anti-colonial feeling as reminiscent of that of the Bolsheviks and communists.Footnote 41 In the opening lines, he compares imperial oppression in India with ‘repressive dictatorships in Italy and Germany’.Footnote 42 This trope of criticizing fascism was one drawn along a clear and increasingly strong distinction between fascism and socialism. Laski also underscores his message with an emphasis on civil liberty and the so-called ‘guardians’ of those liberties, a note he would develop further in years to come.Footnote 43 The foreword was not merely Menon printing Laski's words uncritically but can be read as clear support of Laski's politics expressed in the foreword to a document over which Menon had complete control. The resulting pamphlet was a combination of Gandhian nationalism, the scientific socialism of Nehru, and Laski's neo-Marxist emphasis; a product that was an explicit reflection of Menon's political thought.

Menon had given Laski an outlet to express himself, a platform that beforehand he had not had access to. Indeed, this is clear in what Laski himself said, stating ‘I look back at what I owe Krishna Menon for having made me attend as a member of his army as a debt that I can never repay.’Footnote 44 Their relationship was more than the one-way exchange of ideas, and Menon benefited from more than just Laski's political thought. Laski's inclusion into Menon's world of anti-colonial activism was also a refinement and re-expression of his own politics to different ends; the foreword of India speaks is testament to this. The impact of Laski upon Menon is thus a multi-faceted one that cannot be ignored. Most notable here is the firm foundation that the Laski–Menon relationship helped lay for Menon's career in the world of publishing, and the influential political basis Laski provided Menon.

Although it was not until 1932 that Menon appeared on the payroll of any publishing house, he quickly found himself at two; working for Selwyn & Blount for two years and the Bodley Head for three.Footnote 45 There has been some suggestion that Menon undertook his editing ventures mainly as a means to support himself outside of work for the League.Footnote 46 This seems unlikely as it has often been remarked of Menon's ascetism, living a life bordering on starvation of both food and sleep.Footnote 47 Whilst Menon worked under some instruction, the creative autonomy he held over the two series which he compiled and edited clearly demonstrates his own political views, and how these were to be applied. Both the ‘Topical Books’ series from S&B and the ‘Twentieth Century Library’ commissioned by TBH were largely under the sole influence of Menon.Footnote 48 As such, they were not only moulded by his political ideologies and mission, but also by the contacts whom he increasingly utilized. The leftist connections he made at the LSE were to become not just Menon's contacts but later authors and co-workers.Footnote 49 By looking at the books within these series not just for their content but also who wrote them, the ideological significance of the texts, and what this meant for the wider picture of Menon and British publishing, the interconnected nature of his political development is revealed. This is one that reflects a continued trajectory of the move away from Theosophy and towards a socialist, Marxist, nationalist, and scientific socialist direction.

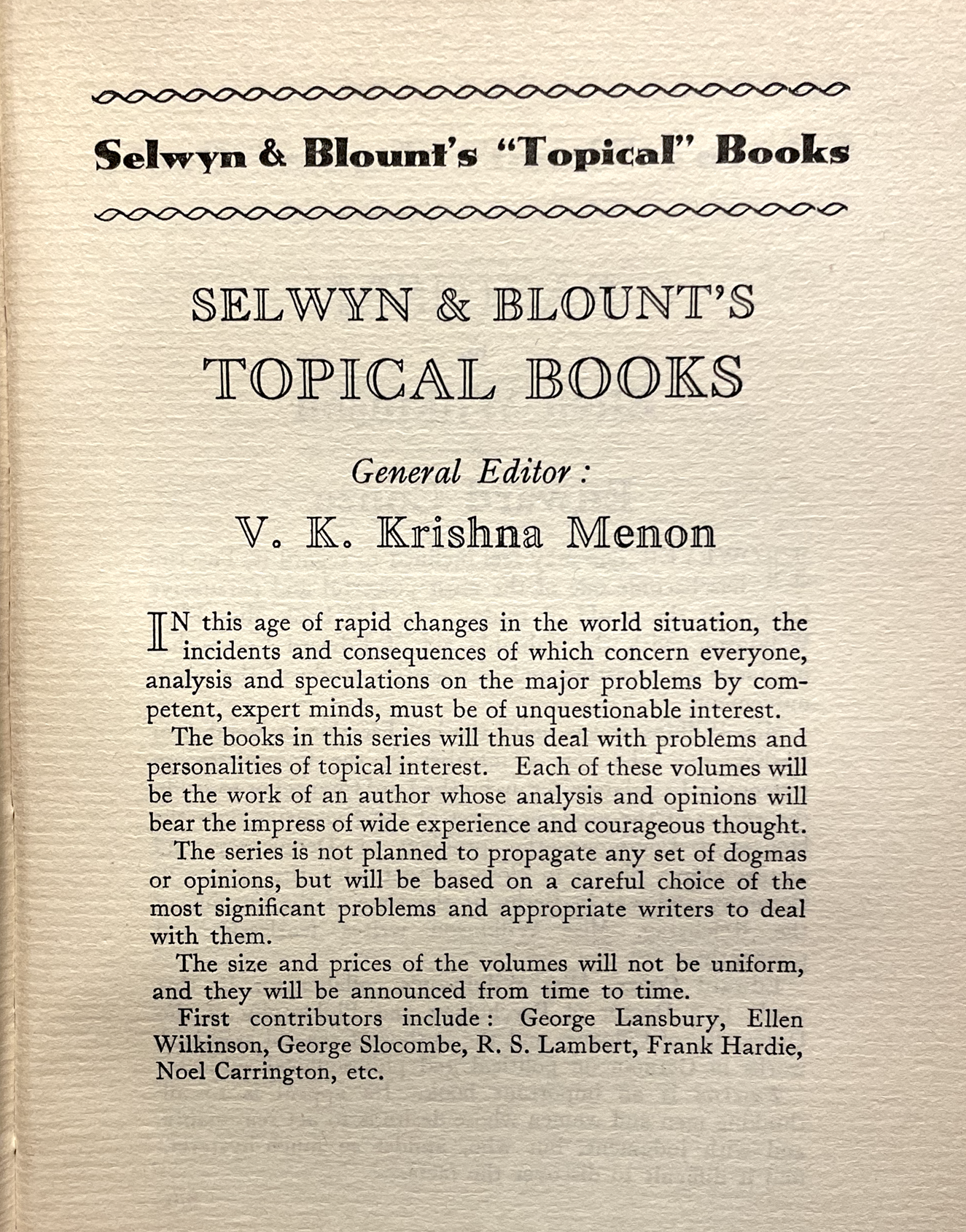

S&B's ‘Topical Books’ series was the first time Menon exercised his political and personal views over a collection of books. The idea of the ‘Topical Books’ themselves, although not Menon's, was a notion he was passionate about beforehand. The series title itself suggests the wider political and social motivations for the series: that in such turbulent times of change the onus should be firmly on the present as well as what the future could bring. The present Menon aimed to focus on was the increasingly turbulent interwar period, characterized to him by an increased internationalist presence, the rise of fascism and subsequent socialist backlash, and developing anti-colonial and nationalist sentiment. The inside cover of each book in the series outlines the purpose of the collection as a whole, and was written by Menon himself.Footnote 50 It states ‘In this age of rapid changes in the world situation, the incidents and consequences of which concern everyone, analysis and speculations on the major problems by competent, expert minds, must be of unquestionable interest.’Footnote 51 The full series overview is shown in Figure 1. By highlighting the world as being in a period of drastic change, it comes with a politically charged wider meaning. This change was one of increased nationalism, fascism, and isolationism. In seeking to not just commentate on these ‘topical’ events but also to speculate, the series reads as a means to make sense of a burgeoning invasion of modernity and global politics. Take for example Ellen Wilkinson and Edward Conze's Why fascism?, a searing overview of the conditions that gave rise to the fascist momentum of the 1930s which, they posit, grew out of a global shift towards defined borders, the unrealization of left-wing mobilization, and an abandonment of previous political tradition.Footnote 52 The series overview also notes ‘The series is not planned to propagate any set of dogmas or opinions, but will be based on a careful choice of the most significant problems and appropriate writers to deal with them.’Footnote 53 However, whilst the titles in the series did deal with ‘problems and personalities of topical interest’, it becomes clear that the opinions and writers chosen to present them were far more in line with the general editor's than ‘the neutral viewpoint’.

Fig. 1. Series overview of the ‘Topical Books’ series published by Selwyn & Blount, taken from George Lansbury, My England (London, 1934).

A cursory glance at some of the books in the series highlights Menon's influence. Young Oxford & war was written by four students including a young Michael Foot, future leader of the Labour party, Frank Hardie, also of Labour, and R. G. Freeman, founding member of Oxford's October Club, a communist group.Footnote 54 This left-leaning group of students reflected Menon's own early Fabianism and his later scientific socialism nurtured at the LSE, tracking the changes influenced under Laski.Footnote 55 Indeed, Laski was even commissioned to write the preface for the book whose striking cover and inside illustrations were designed by socialist and pacifist Arthur Wragg. His illustrations conjure up a solemn and dark air, hinting at the futility of war. The hauntingly constructed image of a spectral professor gliding above ruined buildings is an explicit indication of Wragg's political leanings whilst hinting at Menon's own attitude shown in the series overview.

As noted, Wilkinson and Conze's Why fascism? was also a book in line with Menon's anti-fascist stance and active interest in critiquing the ideology.Footnote 56 The choice of India League member and Labour MP Wilkinson, who also had links to the CPGB and who had by then just completed the fact-finding mission for Condition of India, was supplemented by the choice of German Marxist Conze. Both lent legitimacy and leftist views to the book and reflect Menon's changing attitudes towards radical leftist ideas. His previous hesitancy to embrace Marxism, which had begun to be broken down under Laski, was now fully flexible as he embraced a network expanding to include increasingly hard-left thinkers. Moreover, the inclusion of Wilkinson spoke to a continuation in their relationship that had stemmed from her work for the India League, and her increasing presence in anti-colonial activism.Footnote 57 The font of the main body is from Eric Gill (of Gill Sans font acclaim), who also provided the font and cover for Condition and whose own politics were deeply rooted in a criticism of modernity and a rapidly shifting global order. George Lansbury, then leader of the Labour party, and Noel Carrington and George Slocombe, both left-leaning experts in their fields, also feature in the list.Footnote 58 These were authors gradually being drawn into Menon's ‘web’ of contacts, to borrow the term from Reeves, and reflect more than just a leftist bias.Footnote 59

By drawing on authors with links ranging from the Labour party and the ILP, to those involved with the India League and even some CPGB connections, Menon created a varied series list that was also a reflection of the fluid and interconnected nature of the interwar internationalist left-wing politics. Likewise, it was also an illustration of Menon's own place within this fluid and wide-ranging political melting pot. The ‘Topical Books’ series, although short-lived, was crafted by Menon with clear intentions. These were important books to him, some politically charged, others his personal interests, but nearly all tied in some way to his work with the India League, the British Left, or the LSE. They linked to the India League due to the anti-colonial nature of the texts and authors, often drawing on the same authors and designers for League pamphlets. Similarly left-leaning content was in line with Labour policy and gave a voice to leaders of the party such as Foot and Lansbury, whilst the intellectual arguments brought forward were well-entrenched in the political theory Menon had developed at the LSE.

Menon's editing of TBH's ‘Twentieth Century Library’ followed a similar trend. Although a considerably larger series, Menon's influence on content and authors is apparent again. The overview of the series, shown in Figure 2, is similar to the ‘Topical Books’ series. In the same way as ‘Topical Books’, the focus of the ‘Twentieth Century Library’ was a critique of the fast-moving and sometimes dangerous march of a globally interconnected modern world, and the series overview reads as a searing, even satirical, criticism. Menon, as general editor, points to the swift change taking hold of the world, stating that the books in the series explain ‘the effect on modern thought of the metamorphosis which is affecting every aspect of our civilisation to-day’.Footnote 60 Again, it is with the goal of informing the public on current events and a changing world, and how this impacts everyday life. This overview is more explicit in its goals and fears, and strongly in line with Menon's personal views. The series attacks the fixation upon the twentieth century, but also points to the rapidity of growth; only a short thirty years or so and the series has the entire century emblazoned on its spines. Here, as at S&B, Menon firmly and concretely sets out the series goals and purpose, elevating it beyond a mere collection of texts written by his close contacts, to a political act in and of itself.

Fig. 2. Series overview of the ‘Twentieth Century Library’ series published by the Bodley Head, taken from Eric Gill, Art (London, 1934).

Although a broader series, the authors chosen are again in line with these goals and views. Contributors include J. A. Hobson, a socialist whose writings on imperialism influenced Lenin's notorious criticisms; H. L. Beales, an LSE contact and left-leaning historian who would later join Menon at Pelican; and Ralph Fox, well-known CPGB member.Footnote 61 Hobson's book speaks to democracy as a means and vehicle for protest, hewing a firm anti-imperial line, whilst Beales's Property draws heavily on socialist rhetoric and ideas. The inclusion of Fox is another signal of Menon's increasing acceptance of communist activists, even if he still approached their inclusion in the League with some hesitancy. These three authors neatly capture Menon's continued political move towards the left, and a refinement of his ideas reflected in his choice of authors. His socialism was beginning to be employed for explicitly anti-colonial ends, often taking inspiration from Nehru's scientific socialism and to an extent a continued evolution of Laski's neo-Marxist line. Eric Gill also featured on the list and continued his collaboration with Menon, designing the covers of the series seen in Figure 3.Footnote 62 The illustration, a criticism of the twentieth-century fixations of ‘War and usury’, reflects Menon's developing anti-war sentiments, with his previous pacifist choices whilst working at S&B now being expressed more concretely. The fact that this was undertaken not at a niche, left-wing, small-scale publishing house, but at TBH, one of the largest and most influential, is important too.Footnote 63 Menon had firm notions of what a series should accomplish, and made this clear by selecting these authors and illustrator. The development of the previous collection of ideas and authors from his work for S&B was furthered at TBH, just as Menon's own politics continued to evolve from a loose collection of left-wing beliefs, towards more structured scientific socialist, anti-war, and anti-imperialist foundations.

Fig. 3. Front cover of the ‘Twentieth Century Library’ series published by the Bodley Head, artwork by Eric Gill, taken from Eric Gill, Art (London, 1934).

TBH was also an opportunity for Menon to expand his editorial influence with regards to the independence movement. Following a visit to England in 1935, thoroughly impressed by the work Menon was doing with the India League, Nehru named him his editor in London.Footnote 64 This responsibility came shortly before Nehru sought to publish his upcoming autobiography, Toward freedom, which surely informed his decision.Footnote 65 As a result, Menon suggested that it should be TBH that acquire the rights to publish Nehru's new book.Footnote 66 By giving Menon the authority to manage, edit, and publish his works, Nehru endowed his voice to the editorial hands of Menon. This was not only Nehru entrusting his ideas to Menon but, as Reeves and Louro note, a strong acceptance from Menon of Nehru's own scientific socialist and internationalist ideals.Footnote 67 Writing to the publishers regarding his autobiography in 1937, Nehru affirms ‘Menon has full authority to deal with you in this matter on my behalf and payments may be made to him.’Footnote 68

Menon exercised large control over Nehru's words, a fact that both illustrates the close trust between the two already forming, and the skills and abilities Menon had developed at British publishing houses. For example, to further the readership of Nehru's writings Menon recommended the switch to paperback, drastically increasing sales both in England and India. From 1 January to 30 June 1938, the hardcover copy of Nehru's autobiography sold 234 copies in India. When the paperback was released in India on 15 April 1938 it sold 1,475 copies from then until 30 June. This was over six times as many in just over a month as compared to as in half a year. In the same period, the sales of the English copy went from 11 for the hardback to 781 for the paperback, again in a fraction of the time.Footnote 69 Menon's influence was more than token; instead, he rapidly grew the readership and circulation of Nehru's book. Illustrating the importance of TBH in Menon's editorial and political career, it also suggests the future impact this held in the skills and contacts Menon developed in the publishing world. This was not only an editorial success but the continued development of the ideological and personal relationship with Nehru that would foreground Menon's otherwise surprising influence in independent India.

It was also at TBH that Krishna Menon met Allen Lane who, after quitting the company in 1935 with £100 capital, founded Penguin Books.Footnote 70 Shortly after this, Lane acquired the rights for George Bernard Shaw's The intelligent woman's guide to socialism and capitalism but realized that the colour-coded Penguins had no colour-category for non-fiction. The Pelicans were established to fill this gap for non-fiction imprints. Although there is some debate surrounding whose idea it was for this paperback non-fiction series, largely stemming from the end of Menon and Lane's relationship which after two years of strained co-operation finally broke for good, the contribution of Menon to its early success is widely acknowledged.Footnote 71 Nearly all monographs upon Menon make some mention of Pelican, which is widely seen as his greatest achievement in publishing.Footnote 72 However, what can be overlooked due to the focus on solely Pelican is that Menon's previous publishing work foregrounds his role at Pelican. His publishing and editing work at Pelican followed the same trajectory of political thought from the two previous houses: developing the means to drive for independence, the linking of the Labour party and the ‘Indian Question’, and the importance of print in all of this.

Menon's appointment on the editorial board for Pelican Books was not surprising, and the board was built around Menon's own politics and contacts, demonstrating the importance of his time at the LSE and the two previous publishing houses he had worked for.Footnote 73 Lance Beales, an LSE contact who contributed to the ‘Twentieth Century Library’ series, was brought on board, with his leftist tendencies reinforcing Menon's selections for publication. Also featured was Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell, renowned Scottish zoologist with sympathies for the extreme left. (Interestingly the ‘Penguin Pool’ habitat that Mitchell commissioned at London Zoo was the spot where Edward Young sat to sketch the design for the Penguin Books logo.)Footnote 74 The trifecta of Menon, Beales, and Mitchell created a strongly left-leaning editorial board that Menon was the head of. Following his move away from Laski's neo-Marxism towards a more refined Nehruvian scientific socialism, the choice of Beales and Mitchell speaks to the still-fluid nature of Menon's political thought. Happy to indulge his editors whilst the series found its feet, Lane allowed the leftist slant both to placate and support their work, whilst also being aware of the commercial usefulness of printing left-wing books.Footnote 75 This was a much larger market and considering the paperback as an object was meant to be a cheap consumable for anybody to pick up and read, a leftist flavour to the Pelicans could only be advantageous.

Whilst not all forty of the Pelicans published under Menon can be detailed, it is worth highlighting a few. The first published was Shaw's Intelligent woman's guide that Lane had acquired the rights to prior to Pelican's inception. Menon contacted Shaw asking if he would compose two extra chapters upon sovietism and fascism, and the text was released with an extended title in two volumes in May 1937.Footnote 76 The inclusion of the extra chapters reflects Menon's receptivity and sympathies for soviet rule, a trend that would colour his foreign policy in the years after independence, and his continued editorial war against fascism.Footnote 77 H. G. Wells's A short history of the world reflected socialist and pacifist beliefs which were in line with Menon's, and his book was widely considered a scientific masterpiece, even garnering praise from Albert Einstein.Footnote 78 This reflected Menon's continued anti-war focus, marked even more so with strong socialist response to fascist war-mongering. With the release of two books by Fabian G. D. H. Cole, the leftist-leanings of the Pelicans was well established. Cole's Practical economics and Socialism in evolution developed his notion of guild socialism, and was similar to what Menon would push Nehru for post-1947.Footnote 79 Cole was also a frequent writer for the Left Book Club, co-founded by Laski, and had close connections to many within Menon's circles. Similarly, J. B. S. Haldane’s The inequality of man had much support among Menon's contacts on the left.Footnote 80 Haldane held fairly strong Marxist beliefs and his sister Naomi Mitchison had already written for Menon at TBH. A. N. Whitehead was a good friend of Bertrand Russell, then chairman of the India League, and his Science and the modern world reflected Menon's continued debate of modernity.Footnote 81 R. S. Lambert's Art in England also made the list.Footnote 82 Menon had previously included Lambert's This film business at S&B, whilst Beales had co-authored a book with Lambert.Footnote 83

Menon naturally paid respect to Laski and the guidance and opportunities he had acquired at the LSE, and Liberty in the modern state appeared in the second print run of ten books on 29 October 1937.Footnote 84 Laski, agreeing to have the book reprinted, also wrote a new introduction. However, this was more than the two-page overview of most reprints, but forty pages of commentary on the changes to the world since initial publication and speculation at what was next. In a vein near-identical to Menon in his previous series, Laski highlights and analyses the rapidly changing modern world, growth of populist regimes, and calls of freedom for those suffering under the new world. The new introduction reads as a political tract itself with the opening sentence immediately setting the politically charged tone, as Laski writes ‘the condition of liberty has visibly deteriorated over most of the civilized world’.Footnote 85 This reference to the rise of fascism across Europe forms much of the first half of the introduction. Laski characterizes the prevalence of fascist movements as ‘essentially the expression by capitalism of its sense that it could not arrest the danger of socialist transformation with the framework of democracy’.Footnote 86 Here, he draws the firm battle lines between fascism and socialism, the same line that Menon was ever more invested in. Laski also posits that silence or inactivity against fascism and what he terms ‘losses of freedom’ is tacit acceptance.Footnote 87 This is an echo of his foreword in India speaks, and the sentiment that no action is acceptance was something he admits came from Menon's influence with regards to his until-then silence on colonial India. The introduction ends reading more as a rousing speech, with the repeated use of ‘they will need…’ when describing those who seek liberty, drawing from tried and tested revolutionary rhetoric and pamphleteering, and again reflects a similarity to his piece in India speaks.Footnote 88 Laski's introduction for the Pelican edition is a political and historical overview, endowed with his changing political stance that had developed since the book's first publication as well as since his meeting with Menon. Likewise, it expressed Menon's changing political thought, specifically his move towards a firmer socialist criticism of fascism, underlined by anti-war and anti-capitalist sentiment, and a softening of previously strong scepticism of communism.

Following Menon's departure in 1938, the list almost immediately lost its leftist slant. The following books covered a much broader range of topics and often were completely apolitical. Focusing on poetry, composers, and some religious discussions, the political age of the Pelicans was over. The breakdown of Menon and Lane's relationship can be tracked through the increasingly fractured letters they sent one another, but the politics of titles on the Pelican list did not play a huge part.Footnote 89 Lane, a hard-working and single-focused man, demanded the same of Menon. However, with the India League, the Labour party, and his contacts on the left, Menon was engaged in many projects simultaneously. In late 1938, for example, Menon had to cancel a meeting with Lane due to his work with the India League. He writes ‘as Mr Nehru is in town my time is not altogether free’, and around a fortnight later that he was again not available due to him being engaged with the Labour privy council all week.Footnote 90 It was also during this time that Menon began attaching India League pamphlets to his letters to Lane, in case he should be interested, no doubt further incensing him. Menon's usefulness to Lane had dwindled with the Pelican's commercial success, and skittish Menon had continued to give Pelican as much of his time, or rather as little, as he had at the very start. With his exit from Pelican also came Menon's exit from commercial publishing, with his sole editorial focus from then on being the independence campaign. Although lasting just a few short years, Menon's publishing career had left a large impact upon his politics, whilst conversely he too had impressed upon the world of British publishing an indelible mark.

II

On 17 August 1932, Monica Whately, Ellen Wilkinson, Leonard Matters, and Krishna Menon arrived in Bombay. Menon, with the three Labour MPs, headed up the group and was named the delegation's secretary. They remained in India for eighty-three days, traversing the vast country with the avowed goal of educating the British public of the true condition of India. Months after their return to England they published their findings as Condition of India. The 534-page paperback featured unblinking criticism of British rule grounded in facts and non-sensationalist prose. In the final lines of the foreword, the delegation set out explicitly their position, writing ‘it is our hope that this Report will lead to a realisation on the part of British readers that what passes for BRITISH RULE in India, carried out in their name, would be intolerable to themselves if they lived under it’.Footnote 91 This sets the trend for the whole book which, written to directly address a British audience, confronts the reader with facts, figures, observations, and histories, in an attempt to educate a largely ignorant population. Structurally, the book can be split into two parts, which are interwoven throughout. First are the findings of the delegation, detailing what they saw, who they spoke to, and their impression of the state of the country as a whole; these parts were written by all members of the delegation and then edited by Menon. Second are the sections detailing the background history of India which situates the findings and criticisms. These were composed entirely by Menon and interspersed within the reflections of the delegation. What emerged was a book that shocked those audiences who read it, continued to stir-up anti-imperialist and pro-India League sentiment, and was banned in India a few weeks after publication.Footnote 92 Preceding Nehru's visit in 1935, in which he formally expressed his satisfaction with Menon's work for the League, it contributed to the kickstarting of the two activists’ close political and personal relationship.Footnote 93 In writing and publishing Condition, Menon used the same approach as at S&B and TBH, focusing on both the content of the text and the object of the book itself. His awareness of the advances and gaps in the publishing industry drove the way he went about publishing Condition. Menon's time with Laski and introductions to the British Left had shown him the importance of creating consumable texts, whilst his developing nationalist streak came to be expressed as influenced by Laski; that of educating a naïve public rather than condemning them. This was drawn along anti-war, anti-capitalist solidarity that increasingly expressed itself in how Menon cast his interpretation of scientific socialism and Nehruvian internationalism.

The production and release of Condition highlights the ways in which Menon utilized his work as editor as a political act, and, by extension, as indicative of his political thought. For example, in seeking to produce a quality yet cheap text, Menon called upon Jonathan Griffin, owner and editor of the weekly news bulletin Essential News, which styled itself as ‘a weekly non-party bulletin, made up of quotations, and summations of significant facts’. Condition, itself a collection of facts, observations, and statistics, reads similar to Essential News's own columns and appears to have been the only full-length book the paper published. Condition was printed at the Zenith Press rather than the newspaper's usual Hillingdon Press in Uxbridge. The Hillingdon Press, which printed a wide mix of books and papers, was a low-priced printing operation, whereas the Zenith Press had a richer and more suitable printing history. They had printed books on China, scientific studies for ‘Tropical Schools’, and texts upon Ceylon, Baluchistan, and the Toda tribe of the Nilgiri Hills, and would later print the League's own weekly digest India To-Day. Their books were higher quality and able to last longer, ideal for Menon who wanted Condition to be passed around and read by as many people as possible. Printed on sturdy wove paper and with a uniform size due to its sextodecimo format, the book was priced at 2/6, the same, and often slightly lower, price as many contemporary books. Although Menon had not been able to lower costs to the 6d that the Pelican's would later sell for, the mindset for a cheap yet sturdy consumable was clearly evident. A green paperback cover lowered production costs whilst still standing out on a shop shelf and Eric Gill's cover design, a floral, feather-like leaf, conjures up connotations of a rich and elegant history and the marketable ‘traditional’ Indian design that hinted at ‘the exotic’. This contrasts the spine which with the title in bold letters, the publisher, and the preface by Bertrand Russell, clearly designate it as a serious study.Footnote 94 Russell's introduction was a reminder of Menon's connections with the intellectual left, and his awareness that such a name could lend the publication much legitimacy. Gill also designed the font inside of the book. His font was in keeping with Menon's promotion of his friends and contacts, but also the overall message of an engaging and readable text. The rounded font makes the book appear more approachable rather than an elite text for learned readers. The result of these various publishing decisions undertaken by Menon with specific goals and knowledge was a book that fulfilled his political aims. By using an anti-war publisher, a press that was familiar with colonial literature, artwork, and font by a pacifist and anti-fascist artist, and publicizing a foreword by a renowned left-wing thinker, Menon combined the various aspects of his political thought.

Condition was released to a varied public reception and with considerable backlash as the book reached two distinct readerships. The first were those who were already connected in some way to the campaign for independence, whether that was direct India League membership, readers of pamphlets and newspapers, or those at least aware of the issues in India. Although a readership Menon sought to engage with, public interest in Condition rarely stretched beyond these groups of readers. Part of this may also be due to the second main readership of Condition: government officials, censors, and bureaucrats. Although not as broad a readership, the impact they had on the subsequent circulation and reception of the book was significant.

Members of the British public who read the report were thoroughly shocked at the findings of the delegation, a point that much of the surrounding historiography utilizes when heralding Condition as the League's greatest achievement.Footnote 95 This historical acclaim is mainly due to the growing strength of the League following publication as the report cemented the League's position as the main lobbying group for Indian independence in London, garnering praise from its high-profile supporters such as left-wing journalist H. N. Brasilford, Labour's Julius Silverman, and of course Russell.Footnote 96 It was on this momentum that the League expanded its offices across the country, setting up branches from Bournemouth to Birmingham, Sheffield to Southampton. The release of Condition also coincided with the final figures from Besant's old movement leaving the League, granting Menon complete control of the movement's direction and policy.Footnote 97 Nehru, in his first meeting with Menon, commended him for the good work he was doing with the League and it was this new strength of the lobbying group that developed their initial relationship.Footnote 98 However, whilst the report was a revelation to some readers, the majority of those who picked the book up did so from their own previous interest.Footnote 99 Menon's goal of educating the wider swathes of the British public unaware of the true condition of India was not fully realized as they rarely came into contact with the book. Rather, Condition was released at the right moment, amidst already swirling currents of the League's rise in influence. Condition supplemented, not drove, this growth.

The fact that readership was limited to those who sought the book out was mainly due to the government campaign against both the book and the delegation before the report even emerged. The anti-nationalist propaganda machinery of the India Office swung into action prior to the book's publication, crafting a counter-image of a biased and untrustworthy delegation who had travelled to India on pro-nationalist Congress funds. The letters between Information Officer H. MacGregor and various officials in England and India highlight the lengths they went to discredit the report. For example, at the end of 1932 when the delegation had just arrived back to England, nearly a year before Condition would be published, the director of public information for the Home Department of India wrote to MacGregor upon the premise of quashing the report before it was even written. He writes that counter-measures be undertaken pre-emptively stating to take ‘steps before the delegation themselves start talking…put out suitable material’; MacGregor himself annotated this line with ‘how?’.Footnote 100 In another letter two months later, still prior to the book's publication, MacGregor is berated for not being strong enough with his counter-measures.Footnote 101

This is surprising to read when confronted with MacGregor's own letters in which he attacks Condition. When the Newspaper Society wrote to MacGregor for censorship advice on Condition, he replied rapidly with a scathing warning – so quickly in fact that he responded immediately under the premise of a personal opinion as acquiring the approval for an official view would have taken too long. He writes ‘this is a publication with which no responsible Englishman should be associated…an absolutely false picture of British rule’.Footnote 102 His strong venomous words belie the true worry of censors at how Condition could reach and influence large swathes of the public. Both the content and the book itself, as products of Menon's editing, were seen as having the potential to be heavily damaging. It is perhaps no surprise that this was also the time when MI6 put Menon under close surveillance, tapping his phone lines and intercepting his mail.Footnote 103

Government censors, in fear of Condition, proscribed the book in India under the Sea Customs Act nearly immediately following its release.Footnote 104 Writing to the Lucknow Pioneer MacGregor details six points as to why the book must be banned, referencing that the Congress supplied funds for the delegation's journey and stating how no Indian would have been allowed to publish such a book.Footnote 105 He closes by stating that with low literacy rates and education the report would be misread by an illiterate public. MacGregor's case for banning the book reads as a justification for its undertaking and makes a strong case of the ineptitude of British rule. Interestingly, he ends the letter by instructing ‘Burn or destroy this letter after perusal’, perhaps aware of the shaky grounds his convictions sat upon.Footnote 106 Rather more worryingly is that some of these exaggerations have extended into the historiography surrounding Condition with some historians attributing its findings and ‘success’ to Congress funds.Footnote 107 In actuality, they accounted for less than a third of the budget and were utilized to visit Congress officials, encounters which were contrasted with other meetings with British officials.Footnote 108 The League's response to the backlash was slow to emerge, perhaps as they saw censorship as the strongest testament to the truth of the report. In a letter to the Manchester Guardian, Menon likened the backlash to the kinds of censorship common under repressive regimes in other nations, whilst Wilkinson's response in The Tribune to another smear article took aim at Samuel Hoare, then secretary of state for India, utilizing her platform to detail some of the delegation's findings.Footnote 109 This experience was an important one for Menon who, directly confronted with censorship of his own work for the first time, adopted an attitude of calm and common-sense responses and a belief that the truth would emerge organically. A precursor to his pamphleteering of the 1940s, the backlash to Condition cemented Menon's editorial reaction to government opposition.

Whilst the counter-blasting and anti-nationalist propaganda meant a near radio-silence of adverts and reviews in British newspapers, and a lower public readership, it also points to the achievements of Condition. The ‘poisonous production’, as MacGregor often termed it, had generated great discomfort for government censors.Footnote 110 The smear campaign extended to banning the book in India, pre-emptively launching counter-measures to it in Britain, and publishing damning stories in national newspapers. Ultimately, this meant that whilst Condition did not have the large-scale impact on the British public, or garner a wide and previously unaware readership, Menon's role as editor extended beyond solely this project. Condition represented Menon's contemporary work and acted to combine his various political activities at this time. The three threads of his political action – the India League, the British Left, and his publishing career – came together with Condition. To this end, whilst Menon's own impression that the impact the report had had was below his goal, the importance of the project to Menon's own development was significant. This is the true impact of Condition, beyond the climax of the India League or a footnote in Menon's history, it was the coming together and cementation of Menon's various political activities, all developed under his role as editor.

III

This article has argued for a reassessment of Menon's early political thought through studying his political actions as an editor. As Kapila suggests, Indian political thought, particularly in the case of twentieth-century nationalists, was driven by political ‘actors’.Footnote 111 By assessing the actions of these activists, political actors are transformed into political thinkers.Footnote 112 In the case of Menon, this has meant analysis of the three interconnected threads of his political activism in Britain; his transformation of the India League, his association and work with the British Left, and his editorial career. The way that Menon engaged with these three strands was often tied together through his publishing work, and a book history approach has allowed for engagement with these different political actions throughout his years in Britain. By highlighting Menon playing literary patron to Labour party associates, championing anti-colonial and left-leaning works at bigger publishing houses, and combining these skills in producing India League pamphlets and writings, the interconnected nature of Menon's political activism becomes clear. This has been further illustrated through a study of Condition of India, where Menon employed techniques from his time editing at London publishing houses, supported by Labour party and leftist contacts, to produce a document that was a reflection of his work for the India League. A book history has also highlighted the viability of this approach in the study of twentieth-century empire and anti-colonialism. It allows for engagement with associated printed works, authors, and ideas, on their own terms, whilst teasing out obscured aspects of the works.

Menon's Theosophic ideals were the starting point from which his politics evolved, although these beliefs were soon replaced by Marxist-Fabian leanings under Harold Laski at the LSE.Footnote 113 Laski left an indelible mark on Menon, and although Menon never fully incorporated Laski's neo-Marxist worldview into his own, it provided a firm foundation. The relationship with Laski also lowered Menon's defences to radical leftist projects and although in Britain he rarely accepted communist doctrine, mainly utilizing CPGB contacts for their political sway, the increasing openness with which he accepted communism that was to influence his foreign policy in the future had begun. It was also at the LSE where Menon gained the contacts making a career in publishing viable. This coincided with a growing relationship between him and Nehru owing to Menon's work transforming the India League, and with that, the second foundational layer of Menon's thought began to manifest itself. Indian nationalism, particularly as expressed by Gandhi and Nehru, informed Menon's political actions and drove his work.Footnote 114 Nehru's internationalist outlook fused with a breed of scientific socialism and found fertile soil in Menon's mind. As with Laski, these were not one-way relationships, and Menon's own thought came to influence Nehru and Nehruvian policy.Footnote 115 These changes to Menon's thought were expressed in his publishing work, which also saw Menon take an increasingly anti-war and anti-fascist stance, in turn cementing his core socialist beliefs. His most notable publishing work, that of Pelican Books, followed similar trends and acted as an amalgamation of Menon's editorial skills and experiences up to then, as well as reflecting his political thought. Like Condition, it brought together connections and attitudes within the Labour party and India League members and apparatus, united under Menon the editor. On that chilly August night on the Strand in 1947, Krishna Menon stood as the words of Rabindranath Tagore's poem and India's future national anthem rang out. Just as Tagore's words, once grounded in tradition but soon to be transformed and imbued with fresh meaning and importance, so too was Menon's evolving political thought to be manifested anew in an independent India.

Acknowledgements

My deep thanks to James Poskett for his continuous encouragement and help with this article (and everything else). As ever I must reflect on my immense adoration and gratefulness to my wife Jessica for her unerring love and boundless support. Thanks also to Dan Branch, Luna Bowman, Mandy and Erin Brown, Rachel Leow, both initial reviewers, Bruce Bruschi, Catherine Flynn, Hannah Lowery, Ian Coates, Ceri Lumley, Neil Raj, and the Asian and African Studies Reference Team at the British Library.