Introduction

The Te’omim Cave is a large, complex cave on the western edge of the Jerusalem hills (fig. 1). It was named Mŭghâret Umm et Tûeimîn—“the cave of the mother of twins”—by local residents in the nineteenth century. C. R. Conder and H. H. Kitchener of The Survey of Western Palestine carried out the first comprehensive study of the cave on October 17, 1873. They mapped out the cave and noted a deep pit at its northern end. Their description of the cave provides information about traditions and customs of the locals, who attributed healing properties to the spring water that flowed in the cave.Footnote 1

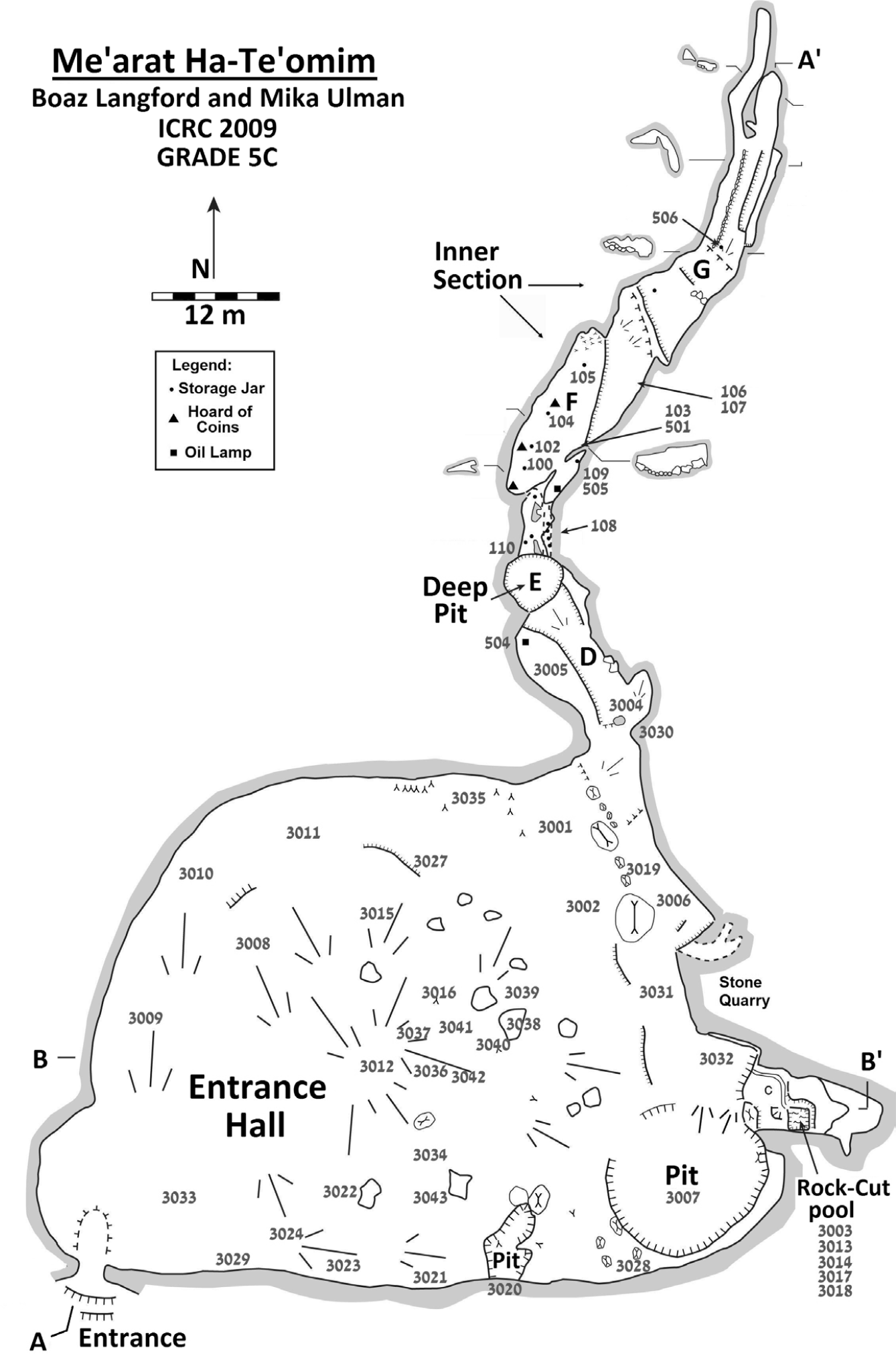

Fig. 1. Plan of the Te’omim Cave (B. Langford, M. Ullman under the Te’omim Cave Archaeological Project)

In the late 1920s, René Neuville, the French consul in Jerusalem, excavated the floor of the cave’s main chamber and found ceramic, wooden, and stone vessels. The finds were dated to the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, the Early Bronze, Middle Bronze, and Iron Ages, and the Roman and Byzantine periods.Footnote 2

From 1970 to 1974, Gideon Mann (a physician and cave explorer) studied the cave on behalf of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel. Mann mapped a section of the cave, found passages leading to inner, hidden chambers, and discovered various items, including pottery and glass vessels.Footnote 3 Since 2009, the cave has been explored by our team as a joint project of the Martin (Szusz) Department of Land of Israel Studies and Archaeology at Bar-Ilan University and the Cave Research Center at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The cave entrance—a natural opening that was widened by hewing—is located above the channel of the wadi. From the entrance one descends northward into a spacious chamber (about 50 x 70 m), most of which is covered by a huge pile of rocks (fig. 2). Several passages and fissures in this rubble lead to underground crevices and cavities, rich in archaeological finds. On the northern side of the chamber, among the stalagmites and columns, an easily traversed path leads to passage D, a wide, high passage leading northward. About 20 meters to the north, the passage is blocked by a karst shaft (E); the diameter of the shaft ranges from 4 meters at the top to 6 meters at the bottom. Its floor is about 15 meters below the floor of passage D, its upper part forming a dome about 3 meters above the ceiling of the passage. The height difference between the ceiling and bottom of the shaft reaches 23 meters (fig. 3).

Fig. 2. The main hall of the Te’omim Cave, looking east (photo: B. Zissu under the Te’omim Cave Archaeological Project)

Fig. 3. Deep shaft in the northern part of the Te’omim Cave (photo: B. Zissu under the Te’omim Cave Archaeological Project)

A square rock-cut pool (with sides 2 meters long) collects water dripping from the ceiling. The water then flows westward through a rock-cut channel. Today, the water is absorbed by the ground, but at one time it was collected in a built pool lower down. Additional channels were carved out in various spots in the entrance chamber to collect dripping water in pools or storage vessels.

Our recent explorations have uncovered finds from numerous periods, ranging from the Neolithic period to the present. The three principal periods are the Middle Bronze Age (ca. 2000–1550 BCE), the end of the Bar Kokhba revolt (ca. 132–136 CE), and the Late Roman–Early Byzantine period (late second to fourth centuries CE). The present article will discuss the Late Roman–Early Byzantine phase.

The Late Roman–Early Byzantine Phase in the Te’omim Cave

Beginning in the late second century CE, the cave—especially its deep pit and interior spring—functioned as a place of devotion. In previous studies we suggested that the cave was consecrated to a chthonic (underworld) deity.Footnote 4

A large assemblage of oil lamps and coins from the Late Roman period, as well as pottery and other items from the Byzantine period, was discovered in the main chamber and its ramifications. About 120 well-preserved oil lamps dating to the Late Roman and Early Byzantine periods (late second to fourth centuries CE) were collected from cavities and crevices in the cave (fig. 4). The lamps had been deliberately deposited in narrow, deep crevices, most of them accessible only by difficult crawling. We had to use long poles with iron hooks to extricate many of them, and long poles had probably been used to insert them initially (fig. 5). The fact that these lamps had been thrust into and buried deep in these hidden, hard-to-reach crevices suggests that illuminating the dark cave was not their sole purpose.

Fig. 4. Group of intact oil lamps discovered in the Te’omim Cave (mostly in L. 3036) in the 2012 season (photo: B. Zissu under the Te’omim Cave Archaeological Project)

Fig. 5. Extricating an oil lamp from a crevice between boulders in L. 3064 (photo: B. Zissu under the Te’omim Cave Archaeological Project)

An assemblage of four ancient objects was found alongside three Late Roman oil lamps in a very narrow crevice in the southern portion of locus 3004. The assemblage, reachable only by stretching out a hand between the boulders, consists of three bronze objects (fig. 6)—an Intermediate Bronze Age axe (B.957) and two socketed spearheads (B.958–959)—and an Early Bronze Age juglet. The question of how these four items ended up in the same narrow crevice together with three Late Roman lamps, with no clear separation between the objects, is hard to answer. If the juglet is indeed from Early Bronze I, then the assemblage is composed of items dating from three different periods. Since it is inconceivable that three deposits were independently placed in the same inaccessible crevice, we assume that the four ancient items were gathered and redeposited in the Late Roman–Early Byzantine period, together with the oil lamps, as part of cultic activity.Footnote 5

Fig. 6. Photo of three bronze objects (an “eye axe” and two socketed spearheads) (photo: Tal Rogovski under the Te’omim Cave Archaeological Project)

One of the cavities is locus 3036, a system of interconnected crevices located underneath large, collapsed boulders in the center of the entrance chamber. In one of its crevices, five Late Roman–Early Byzantine oil lamps, deposited together with a Middle Bronze II bowl, were found in situ (figs. 7, 8). Three lamps were found underneath the bowl and two others were near it. The much older bowl seems to have been found elsewhere and intentionally deposited together with the lamps in Late Antiquity.

Fig. 7. Oil lamps and a MBII bowl in situ in crevice L. 3036 (photo: B. Langford under the Te’omim Cave Archaeological Project)

Fig. 8. Finds from L. 3036: Three oil lamps (left) were found underneath the MBII bowl, and two oil lamps (right) had been placed near it (photo: B. Zissu under the Te’omim Cave Archaeological Project)

During the survey of the cave, three human craniums were found inside hard-to-reach crevices and beneath large rocks in the central chamber—near a large depression, near the entrance to the inner part of the cave, and near the rock-cut pool. No additional human bones were found with the craniums. Because two of the craniums were discovered in crevices and with no other finds nearby, we initially believed that they had been moved there by rats after having originally been placed elsewhere. The third cranium was found in situ in a hard-to-reach crevice (L. 3049), covering four ceramic oil lamps of local types typical of the third and fourth centuries CE (fig. 9). This find supports the possibility that the cranium’s location is not a coincidence. The craniums and lamps seem to have been placed there together deliberately, in one time period—namely, the Late Roman period—and to have served a single purpose for whomever put them there.

Fig. 9. Finds from L. 3049: oil lamps found underneath the upper part of a human skull (frontal and parietal bones) (photo: B. Zissu under the Te’omim Cave Archaeological Project)

Due to the archaeological context of the finds and their location inside the cave, we assume that the craniums were placed together with the oil lamps as part of a ritual of magic, conducted in the cave in that period. Examination of both the written sources and the archaeological finds may indicate the type of ritual that took place in the cave, involving the use and hiding of human craniums, lamps, and bowls, together with metal weapons and other artifacts dating to much earlier periods.

Identifying magical practices in the archaeological evidence is not simple. Magical practice is used in ritual acts that are undertaken, mainly by individuals, to achieve a desired effect. Sometimes the practices should be carried out in a specific locationFootnote 6 or require the use of specific material culture. Therefore, to locate magic in the archaeological context, we must trace material evidence for those practices. Andrew Wilburn has suggested using the classical literary and documentary evidence to identify items that were frequently employed in magical rites. Among the material categories that are mentioned in the magical ancient sources, Wilburn notes usage of parts of human and animal bodies to establish a connection to the victim, and household items that have been repurposed for magical use.Footnote 7 In accordance with this perception, in the following paragraphs we will discuss the various finds discovered in the cave while examining their uses in ancient magical literature and their occurrence in parallel archaeological contexts.

The Use of Human Skulls for Necromancy and Other Purposes

Classical sources hardly mention the consecration or use of skulls at all—probably because they were used mostly for secret rites involving necromancy and communication with the dead, mainly by witches. These rites were usually conducted within tombs or burial caves,Footnote 8 but sometimes they took place in a nekyomanteion (or nekromanteion)—an “oracle of the dead.” These shrines were generally located in caves or next to water sources that were believed to be possible portals to the underworld. These caves were associated with legends concerning the descent of Persephone to the underworld or the rise of Cerberus from the underworld. They always included a shaft leading to the underworld, through which the dead could rise. According to Daniel Ogden, there was a local oracle of the dead near almost every city in the Greco-Roman world. Nevertheless, in his opinion the establishment did not endorse these shrines or the rites conducted in them, and as a result there are no epigraphic finds on the subject. Consequently, these shrines and rites are hard to identify with certainty.Footnote 9

Necromancy was accepted in the Levant and the ancient East. There are many references to it in the Bible, such as the story of Saul having the prophet Samuel conjured up at Ein Dor (1 Sam 28:7–24). The act was viewed negatively, as adoption of the customs of the surrounding nations, and was therefore punishable by death.Footnote 10 The practice is well documented in Mesopotamia, where cuneiform tablets from the first millennium BCE were found containing cultic texts detailing rituals for consulting with spirits by means of human skulls. One document mentions the participation of the sun god Šamaš in the ritual: “Dust of the Underwor[ld …] May he bring up a ghost from the darkness for me! May he [put life back(?)] in the dead man’s limbs! I call [upon you], O skull of skulls: May he who is in the skull answer [me!] O Šamaš who brings light in.”Footnote 11

References to necromancy appear in Greek and Roman literary sources.Footnote 12 The earliest such source is Homer’s Odyssey, where the witch Circe helps Odysseus consult with the prophet Teiresias.Footnote 13 In the Roman period, necromancy was viewed negatively and was sometimes associated with human sacrifice. Laws were passed against witchcraft, divination, and human sacrifice in the Imperial period and even earlier. In 97 BCE, the Roman Senate outlawed human sacrifice.Footnote 14 There is evidence, however, that the emperors Nero, Hadrian, Commodus, Caracalla, and Elagabalus used necromancy to predict the future. Testimonies about the practice became more frequent beginning in the late second and early third centuries CE.Footnote 15 Eusebius notes that the emperor Valerian (253–260 CE) was persuaded by an Egyptian sorcerer to slit children’s throats, sacrifice children, and inquire of the entrails of newborns how to achieve prosperity and success.Footnote 16 Similar actions are attributed to the emperor Maxentius (306–312 CE ). These accounts were probably meant to depict the emperors negatively and to stress their brutality because they were enemies of Christianity.Footnote 17 In 357 CE, necromancy was outlawed conclusively by the emperor Constantius II. A report on this law is preserved in the Codex Theodosianus and the Codex Justinianus; it prohibited all forms of divination, communication with demons, disturbance of the spirits of the dead, and nocturnal sacrifices. Ammianus Marcellinus reports that the punishment set for violators of the law was death. The law was prompted by the emperor’s mounting fear that sorcery would be used against him.Footnote 18

Literary sources from the second through fifth centuries CE note the use of human skulls or heads in ceremonies conducted to raise the dead at oracles. Lucius Apuleius alludes to the use of skulls to raise the dead in his book Apologia, written in the mid-second century CE: “But remember, it would be just as absurd to argue that obscenely-named sea creatures are desired for sexual purposes as to say that one wanted a comb fish to comb one’s hair, a hawk fish to catch birds, a boar fish to hunt boar, sea skulls to raise the dead.Footnote 19

Philostratus (second–third centuries CE) reports that there was an oracle on the island of Lesbos where one could hear the prophecy of Orpheus from his severed head. The oracle was known throughout the region—all the way to Babylonia and Persia. According to the following passage, the worship of Orpheus’s head took place in a shaft, cave, or underground chamber: “For after the women had done their work, his head drifted to Lesbos, lodged in a chasm on Lesbos and sang its prophecies in an earthen chamber.”Footnote 20

Artistic scenes describing the prophecy of Orpheus from his severed head appear on Attic red-figure vessels from the fifth century BCE. On one Athenian hydria, the head of Orpheus appears next to rocks and surrounded by muses. Above the head is a male figure holding two ropes and extending his hand toward the head. The figure’s left foot rests on the rock in front of the head. This seems to be a depiction of a believer who went down to the shaft at the oracle on Lesbos where Orpheus’s head was in order to hear prophecy.Footnote 21

The third-century-CE Christian theologian Hippolytus of Rome tried to discover the trick behind the speaking skulls in the divination rituals. This is evidence of the frequency of the practice.

They place a skull on the ground and make it appear to talk in the following way. It is made of an ox’s caul that is molded on Tyrrhenian wax and freshly mixed gypsum. When the membrane is spread around it, it has the appearance of a skull. It seems to speak to all when an instrument is operated, the use of which I also related in the case of the boys. Preparing the windpipe of a crane or some other longnecked animal, a fellow jester secretly attaches it to the skull, uttering what he wants. If he wants it to disappear, he surrounds it with a heap of coals and appears to offer incense. The wax, absorbing the heat from the coals, melts, and so the skull is thought to disappear.Footnote 22

Consultation of a human skull is also part of a tradition attributed to King Cleomenes I of Sparta and mentioned by the Roman writer and rhetorician Claudius Aelianus (late second–early third centuries CE):

Cleomenes the Laconian chose Archonides from among his friends to share in his activities. He swore that if he acquired power, he would do everything with the aid of his friend’s head. When he came to power he killed his friend, cut off his head and preserved it in honey. Before taking any action he would bend over the pot, to announce what he was doing, and so he claimed not to be in breach of his oath or undertaking, because he was consulting with Archonides’ head.Footnote 23

The tradition about Perseus and the head of the Medusa as reported by the sixth-century Christian historian John Malalas suggests that religious rituals involving human skulls and their powers were also known in his period and that the story was adapted to practices widespread at the time. Malalas notes that Perseus’s father taught him sorcery, including a type involving a “skull-cup” (skyphos). After his father’s death, Perseus consulted an oracle and set out for Libya. On the way he saw a girl with wild hair. When he asked her her name, she said it was Medusa. Perseus decapitated her and immediately started using her head for magical purposes. He subsequently carried it with him everywhere so that it would help him fight his enemies.Footnote 24

The use of skulls for sorcery and the associated rituals are mentioned in several papyri written in Greek in the fourth and fifth centuries CE. These papyri, found in Egypt, are part of a collection known as Greek Magical Papyri (PGM). These are remnants of books of sorcery, most of which were destroyed by the establishment. The documents in the collection are from the second century BCE through the fifth century CE and vary in their origins and nature. They include individual spells and magical formulae, as well as compilations of spells and formulae collected by sorcerers.Footnote 25 Because the papyri were found in Roman Egypt, they reflect extensive religious and social pluralism. We can see in them a strong influence of the Egyptian religion but sometimes other influences as well: Greek, Jewish, and more.Footnote 26 One spell explains how to restrain and seal the mouths of skulls so that they won’t say or do anything.Footnote 27 Another shows how to raise the spirit of the dead with a disinterred skull: a spell is written in black ink on a flax leaf, which is then placed on the skull.Footnote 28 The purpose of another spell is to obtain assistance and protection from spirits by using the skull of Typhon (probably a donkey) on which a spell is written in the blood of a black dog.Footnote 29

These magical instructions are reminiscent of a recently published Jewish oath in Aramaic inscribed on a human skull from an unknown source. The skull was purchased in the antiquities market by the collector Shlomo Moussaieff and apparently originates in Babylonia (Mesopotamia). Dan Levene examined the inscription along with three other skulls from museum collections in Philadelphia and Berlin that have oath inscriptions. He suggests that this skull is an example of the use of incantation bowls against demons, as was common among Babylonian Jewry in the third through seventh centuries CE.Footnote 30 Despite the rarity of such finds in Jewish society, it illustrates the use of human skulls for protection from spirits and demons, as was common in Babylonia, in Egypt, and throughout the Greco-Roman world.Footnote 31

The rabbis were aware of the use of skulls for necromancy. Both the Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud note that necromancers would use skulls to raise the dead:

Our rabbis taught: A ba’al ov denotes both him who conjures up the dead by means of soothsaying and one who consults a skull. What is the difference between them? The dead conjured up by soothsaying does not ascend naturally [but feet first] nor on the Sabbath; whilst if consulted by its skull it ascends naturally [i.e., head first] and on the Sabbath too.Footnote 32

And one who asks the dead: Some Tannaim state: this is one who interrogates a skull. Some Tannaim states: this is one who interrogates his masculinity. What is the difference between one interrogated by his skull or one raised by his masculinity? The one interrogated by his skull rises normally, rises on Sabbath, and a commoner can raise a king. But one raised by his [masculinity] does not rise normally, does not rise on Sabbath and a commoner cannot raise a king.Footnote 33

Caves, too, were perceived by the rabbis as places of idolatry: “Levi said: One who worships a house makes it forbidden, a cave he does not make forbidden. What is between a house and a cave? Rebbi Hanina ben Rebbi Hillel said, A house was separated [from the ground] at some time; a cave never was separated.”Footnote 34

The Mishnah reports that R. Shimon b. Shatah hanged eighty women in Ashqelon on one day.Footnote 35 According to a story in the Jerusalem Talmud, the eighty women were witches in a cave near Ashqelon who were subverting the world.Footnote 36 Based on the components of the legend, Joshua Efron suggests that the witches were active in the local cult of the fertility goddess Aphrodite and her Canaanite counterpart Derketo or Astarte, who had chthonic associations. Efron believes that the cave where the witches conducted their cultic activities was a burial cave with mythological wall paintings located near the city.Footnote 37 The fourth-century church father Epiphanius, a native of a village near Eleutheropolis (Beth Guvrin), tells of similar rituals conducted in his lifetime in the cemetery near the Hamat Gader bathhouses:

Then, when his helpers learned of the passion the boy had betrayed for the girl, they undertook to equip him with more powerful magic—as Josephus himself described to me minutely. After sunset they took the unfortunate lad to the neighboring cemetery (in my country there are places of assembly of this kind, called “caverns,” made by hewing them out of cliffsides). Taking him there the cheats who were with him recited certain incantations and spells, and did some things, with him and in the woman’s name, which were full of impiety.Footnote 38

Epiphanius’s testimony—combined with the story of Shimon ben Shatah—indicates that such rituals were conducted in Palestine in the Roman period and the beginning of the Byzantine period. Epiphanius’s statement about rock-cut caves in the cliffs of his country (probably referring to Palestine) that were used for witchcraft is important to our subject because his description closely resembles the entrance to the Te’omim Cave and the rock-cut steps leading to it, carved out of a cliff wall in the northern bank of a wadi about 22 kilometers from Eleutheropolis.

As far as we know, other than the use of skulls for sorcery and necromancy, rituals involving human skulls are hardly ever mentioned in classical sources. Those that are mentioned relate mainly to “barbaric” practices of tribes or nations located outside the borders of the empire that included human sacrifice or headhunting. Several classical authors note that the Gauls, when returning from battle, would place the severed heads of their enemies around their horses’ necks; when they reached home they would stick these heads on spears and hang them or otherwise place them in the doorways of their homes. They would preserve the heads of enemy commanders in pine oil to be shown to strangers as symbols of their victory in battle.Footnote 39 Livy adds that when the Gauls defeated Postumius in the third century CE, they chopped off his head and brought it to their most important temple as a demonstration of their victory. There, they removed the flesh and adorned the skull with gold, before using this skull in religious rites and ceremonies.Footnote 40 A similar story is told by HerodotusFootnote 41 and StraboFootnote 42 about the Scythian tribes north of the Black Sea.

The archaeological record from the Roman Empire of human skulls deposited in possible portals to the underworld—caves, shafts, and water sources—is not extensive. Many sites from the sixth through first centuries BCE in the area settled by the Thracian tribes west of the Black Sea contain abundant evidence of human sacrifice in rock-cut shafts. In some of the shafts only human skulls were found, without the rest of the skeleton. It has been proposed that these were cultic shafts used by the Thracians in fertility and life-cycle rituals.Footnote 43 Almost no evidence of such rituals has been discovered from the time of Roman rule in Thrace; apparently, the Thracians stopped engaging in human sacrifice or depositing skulls in shafts in this period.

The consecration of human skulls as cultic offerings was also widespread in the Celtic world before the Roman conquest, and these rituals continued to be conducted in western Europe during and even after the Roman period.Footnote 44 In her study of Celtic religious practices, Anne Ross notes that the human head is the most common cultic symbol throughout the Celtic region. It is the paramount element in Celtic art and religion. The Celts believed that the soul was located in the head, which was apparently symbolic of divinity and chthonic powers.Footnote 45 Ross stresses the connection between the Celtic cult of the human head and water sources—especially wells, pools, and springs—and presents the archaeological record throughout Britain (from the pre-Roman and Roman periods), which includes skulls deposited in water sources.Footnote 46 In another article she discusses the cultic connection to cisterns and shafts and shows that these were central cultic places for the Celts.Footnote 47 In this context it was proposed that the Gallic-Celtic culture, in its worship of chthonic deities and the forces of the earth, regarded cisterns, shafts, and even springs as entrances to the world of the dead.Footnote 48

The depositing of human skulls in shafts and wells continued after the Romans conquered the Celtic regions and even after they withdrew from Britain;Footnote 49 the main evidence from this period comes from Britain. Miranda Green even stresses that “there is, indeed, a mass of material from Roman Britain arguing for the retention of head-related ceremonial action, despite the ‘civilising’ influences of Mediterranean tradition.”Footnote 50 Even after the end of Roman rule in Britain, the local population preserved folk traditions linking human skulls to water sources, especially wells. According to Christian traditions from Britain, the origin stories of many wells are related to the place where the severed head of a Christian martyr fell.Footnote 51

The Use of Oil Lamps, Bowls, Axes, and Swords/Daggers in Necromancy

Although oil lamps are utensils for everyday use, in certain contexts—or if they are found in large quantities or in unexpected places—their function can be interpreted differently. Such conditions can indicate a ritual context for their deposition.Footnote 52 The use of oil lamps for divination (lychnomancy or lampadomancy) was extremely widespread in the classical periods. The prophetic force behind the lamp was believed to be a spirit or spirits, or in some cases even gods or demons. Divination by means of oil lamps was done by watching and interpreting the shapes created by the flame. A boy usually served as medium.Footnote 53 Deposition of oil lamps within active or abandoned sacred precincts, often at or near water sources, are known from different sites in the Greek and Roman world, but usually the purpose for the depositions and the actual rites that were performed remain unknown. A few parallels from the Roman world are worth mentioning. In the northern part of Palestine, at the sanctuary of Pan at Paneas/Caesarea Philippi, around 3,000 oil lamps from the Late Roman period were found under structures built on the sanctuary’s terrace. Berlin suggested that the large quantity of lamps dedicated by worshipers probably indicates the existence of rites related to a mystery cult, or perhaps an oracular shrine.Footnote 54

The remains of a few divination places were found in southern Greece. Over 4,000 oil lamps were discovered in a subterranean structure in the hollow of a cliff at the western edge of the Gymnasium of Corinth, thereafter called “the Fountain of the Lamps.” Initially built in the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods, the structure was reused in the Late Roman period as a cult room and repository for votive oil lamps.Footnote 55 At Nemea, S. G. Miller has found three cisterns containing a large number of oil lamps from the third century CE. Miller regarded the assemblage as remains of a lychnomanteion, a prophetic sanctuary that functioned in the abandoned sacred area.Footnote 56 Not far away, at Patras, another lychnomanteion from the first to third century CE was identified near the harbor of the city, where 395 oil lamps were deposited, some of them inscribed with magic words and letters.Footnote 57

At Rome, excavations in the area of the sacred spring of Anna Perenna showed that the site was venerated from at least the first century BCE to the end of the fourth century or the beginning of the fifth century CE, when the fountain was blocked with broken amphorae, apparently as a result of the Theodosian edict that suppressed non-christian cults. The cultic practices included tossing oil lamps with metal defixiones into the water of the fountain. At least 72 oil lamps of the first half of the fourth century CE were uncovered.Footnote 58

Rituals using lamps for divination are often mentioned in Demotic Magical Papyri and attest to Egyptian influence.Footnote 59 One spell, which combines lychnomancy and lecanomancy (divination by means of reflections of a liquid in a bowl), is intended to raise the souls of the dead from the underworld to the rim of a vessel containing water and oil, with the help of the Egyptian god Mihos, in order to speak with the boy acting as medium. This spell also mentions a curse meant to raise the souls of the dead via the rim of the oil lamp.Footnote 60 Oil lamps and a ceramic bowl were found together in a narrow crevice in the center of the cave (L. 3036), possibly alluding to a cultic ritual similar to that mentioned in this papyrus. Another spell mentioned in the same papyrus refers clearly to a god rising through the flame of the lamp. Footnote 61 An English translation of the text is as follows:

Another manner of [doing] it also; [it is] very good for the lamp. You should [say] “BOEL BOEL I I I A A A TAT TAT TAT, the first servant of the great god, he who gives light exceedingly/the companion of the flame, in whose mouth is the flame, he of the flame which is never extinguished, the god who lives, who never dies, the great god, he who sits in the flame, who is in the midst of the flame, who is in the lake of heaven, in whose hand is the greatness and might of the god, come into the midst of the flame. Reveal yourself to this youth here today, have him inquire for me concerning everything about which I shall ask him here today, for I shall praise you in heaven before Pre; I shall praise you before the moon; I shall praise you on earth; I shall praise you….” If the light has not come forth, you should have the youth himself speak with his mouth to the lamp.Footnote 62

The use of oil lamps for necromancy or consulting with spirits and deities is also mentioned in Greek papyri in the same collection of spells.Footnote 63 One such spell, which asks the god Besas about the future, contains the following magical formula to be said to the lamp: “Formula to be spoken to the lamp: ‘I call upon you, the headless god, the one who has his face upon his feet; you are the one who hurls lightning, who thunders, you are [the one whose] mouth continually pours on himself….’ ”Footnote 64

Oil lamps are associated with spirits and the dead in several classical sources.Footnote 65 In his Natural History, Pliny cites Osthanes, a Persian magus who accompanied Xerxes on his invasion of Greece in the fifth century BCE and who introduced sorcery and magic to the Greeks, regarding accessories used in sorcery: “As Osthanes said, there are several forms of magic; he professes to divine from water, globes, air, stars, lamps, basins [bowls (pelvibus)] and axes, and by many other methods, and besides to converse with ghosts and those in the underworld.”Footnote 66

Interestingly, Pliny mentions the use of axes and lamps in magic. Indeed, an axe head from the Intermediate Bronze Age was found, together with a juglet, two spearheads, and ceramic oil lamps from the Late Roman period, in a deep crevice (L. 3004) near a shaft in the inner section of the Te’omim Cave.

Daggers and swords, too, such as the bronze daggers from the Intermediate Bronze Age discovered together with Late Roman oil lamps at locus 3004 and locus 3064, were associated with necromancy and divination. They served primarily to protect the believer from evil spirits and to ensure that offerings to the specific spirit being conjured up were not seized by other spirits. These offerings might include objects that were customarily given to spirits during funerals in antiquity.Footnote 67 Accordingly, when Odysseus deposited an offering into the shaft of Teiresias, he had to wield his sword against other spirits. This scene appears in several jar paintings.Footnote 68

But when with vows and prayers I had made supplication to the tribes of the dead, I took the sheep and cut their throats over the pit, and the dark blood flowed. Then there gathered from out of Erebus the ghosts of those that are dead, brides, and unwed youths, and toil-worn old men, and frisking girls with hearts still new to sorrow, and many, too, that had been wounded with bronze-tipped spears, men slain in battle, wearing their blood-stained armor. These came thronging in crowds about the pit from every side, with an astounding cry; and pale fear seized me. Then I called to my comrades and told them to skin and burn the sheep that lay there killed with pitiless bronze, and to make prayer to the gods, to mighty Hades and dread Persephone. And I myself, drawing my sharp sword from beside my thigh, sat there, and would not allow the strengthless heads of the dead to draw near to the blood till I had inquired of Teiresias.Footnote 69

Silius Italicus reports that Scipio Africanus went to a cave containing a portal to the underworld. There he encountered a Sibyl, who asked him to dig a channel in the earth with his sword and instructed him to use his sword if unwanted spirits came toward him from the underworld.Footnote 70 The story of a man who ran with sword drawn toward a spirit is found in a book by the first-century-CE Latin author Petronius.Footnote 71 Lycophron mentions explicitly that spirits and the dead are afraid of swords: “And he shall come to the dark plain of the departed and shall seek the ancient seer of the dead, who knows the mating of men and women. He shall pour in a trench warm blood for the souls, and, brandishing before him his sword to terrify the dead, he shall there hear the thin voice of the ghosts, uttered from shadowy lips.”Footnote 72

From these and other sources, we see that spirits were frightened of metal—especially bronze and iron—and that one could control them by means of implements made of these materials.Footnote 73 The Greek Magical Papyri, too, contain references to the use of a sword or dagger. For example, one spell for predicting the future involves drawing a picture of the god Bass with a sword in his right hand.Footnote 74

Discussion

The Te’omim Cave in the Jerusalem hills has all the cultic and physical elements necessary to serve as a possible portal to the underworld. It is a subterranean space with a deep shaft at one end; a spring flows in the cave, and its waters are collected in a rock-cut pool; and there are traditions attributing powers of fertility and healing to the cave. Based on the discovery of oil lamps deposited in crevices throughout the cave, including near the spring pool and the deep shaft, we suggested previously that chthonic deities associated with the cycles of nature, life, and death were worshiped in the cave in the Late Roman period. We also showed that evidence of such a cult from the Late Roman period is found at several additional sites throughout Judea.Footnote 75 In this context, it is worth noting that a cultic site seems to have existed in the Grotto of the Nativity in Bethlehem from the time of Hadrian to the reign of Constantine.Footnote 76 As the site was consecrated to the local god Tammuz-Adonis, it seems that the cultic traditions and ceremonies practiced there were those of the eastern part of the empire and the Levant.

Most of the objects discovered in hard-to-reach crevices in the Te’omim Cave, including the oil lamps, the ceramic and glass bowls and vessels, the axe head, and the daggers, were used in one way or another for sorcery and magic in caves perceived as possible portals to the underworld. Their purpose was to predict the future and conjure up the spirits of the dead. Because more than 100 ceramic oil lamps but only three human skulls have been found so far in the Te’omim Cave, we hypothesize that the primary cultic ceremony focused on depositing oil lamps for chthonic forces, perhaps as part of rituals conducted in the cave to raise the dead and predict the future. Nevertheless, the human skulls suggest another element of the cultic ceremonies held there. Although most archaeological finds related to the worship of human skulls in the Roman Empire are in Britain (see above), we cannot conclude that Britons brought the practice to Palestine from the far end of the empire. Rather, from the variety of aforementioned sources (classical, Christian, and rabbinic) from the Late Roman period and beginning of the Byzantine period (the time of the cultic practices in the Te’omim Cave), it is clear that human skulls were used throughout the Roman Empire, including in Palestine and the vicinity, in necromancy ceremonies and communication with the dead. These ceremonies were conducted primarily in burial caves and caves with possible portals to the underworld. Apparently, the large number of human skulls deposited in Britain attests to the frequent use of magic and necromancy in that region of the empire. This is reinforced by Pliny’s comments about the spread of sorcery and magic throughout the Roman Empire, especially to the Gallic provinces and Britain.Footnote 77

In light of all this, we can propose with due caution that necromancy ceremonies took place in the Te’omim Cave in the Late Roman period, and that the cave may have served as a local oracle (nekyomanteion) for this purpose. The Te’omim Cave is located approximately midway between the city of Aelia Capitolina and Eleutheropolis, near the geographical boundary between the Jerusalem hills and the Judean Shephelah. This location is in the heart of the region populated by gentiles in the Late Roman period, after the failure of the Bar Kokhba revolt.Footnote 78 Consequently, and despite hints that the practice existed to a limited extent even among the Jewish population, we suggest that the participants in the cult in the cave were mainly non-Jewish residents of the area.

To sum up, the identification of the Te’omim Cave as a local oracle (nekyomanteion) and the analysis of the archaeological assemblage is in our opinion an outstanding test case worth examining within the developing discipline of the “archaeology of magic.” The findings and their specific archaeological contexts provide a better understanding of divination rites that were probably held in the cave and shed a more tangible light over the spells of the Greek and Demotic Magical Papyri.