In 2007, Marine Le Pen chose Hénin-Beaumont, a former mining town in the far north of France, as her political base. That year she stood as a candidate there in the legislative elections, and over the following decade the town became a symbol of her leadership and electoral success. Since taking the reins of the Rassemblement National (RN) in 2011, formerly known as the Front National, a key strategy has been that of dédiabolisation or ‘de-demonization’.Footnote 1 This is the process by which Le Pen and colleagues have sought to construct a new mainstream political image with broadened appeal.Footnote 2 In 2014, the RN gained control of the local government of Hénin-Beaumont. According to Le Pen and the incoming mayor, Steeve Briois, the town was to be used as the vitrine, a showcase or shop window, to demonstrate a ‘cleaned-up’ image of the central party as ‘normal’.Footnote 3

Existing research is conflicted over the extent to which populist radical right (PRR) parties like the RN retain and implement their ideology when in government or are ‘tamed’ by the experience (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015: 9–10). This article analyses the exercise of power of the RN at the local level of government in Hénin-Beaumont and the extent and manner of mainstreaming. A municipal-level focus enables the novel inclusion of the contemporary RN in this debate – one from which it is usually absent due to its lack of governing experience at either the national or regional level – and an investigation of the mainstreaming process in local government which has been neglected in the literature. Although subnational arenas are often assumed to play a role in the mainstreaming process of radical parties, analysis of this process is hitherto absent.

The importance placed on the party's control of Hénin-Beaumont (and other towns) as part of the strategy of dédiabolisation has not yet received detailed academic attention. Analysis of the particular subnational approach of the RN demands a change in perspective from national-level analyses of mainstreaming. Rather than the usual consideration of policy-seeking radical parties, constrained and to some extent moderated by the transition to government, we instead focus upon the RN's strategic use of local government office to project an image of moderation. This article thus asks the following research question: To what extent is mainstreaming of the RN evident in its leadership of the local government of Hénin-Beaumont?

To answer this question, we analyse the discourse of the RN elected officials in the local government of Hénin-Beaumont, drawing from mayoral statements, semi-structured interviews with local politicians and journalists, and local press coverage over a five-year period. We analyse, first, the salience of different issues in the party's policy outputs and its framing of them, and, second, the RN's framing of antagonistic political relations. We find that a partial mainstreaming of the RN in the position of local government leadership has indeed occurred, in accordance with some, but not all, of our theoretical expectations. Yet we argue that the party's actions follow from a strategic aim to showcase its competence in (local) government participation, rather than moderation as a simple result of the (often mundane) responsibilities of the role of mayor.

Mainstreaming of the populist radical right in power

Moderation of radical parties through democratic participation

The RN is an archetypal example of the populist radical right. Members of this party family share the core ideological traits of authoritarianism, nativism and populism, and hold radical positions on related policy issues which distinguish them from the mainstream (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Such radical parties are commonly expected to moderate as a result of their institutional adaptation to democratic participation. ‘Inclusion-moderation’ theories offer a number of routes by which this can take place. First, according to the Downsian logic of the median-voter theorem, parties may relinquish their more radical goals due to the pressure of electoral participation and the prioritization of vote-maximizing and office-seeking strategies (Downs Reference Downs1957; Downs et al. Reference Downs, Manning and Engstrom2009). Second, electoral campaigns and policy development require professionalization of their organization, resulting in the promotion of pragmatists over radical firebrands (Michels Reference Michels1968). Radical parties that go on to attain positions of government responsibility are expected to moderate through several additional mechanisms. Third, when a coalition with a mainstream party is required, adjustments of radical positions are likely to be demanded in the negotiation process and throughout the governing period (Dunphy and Bale Reference Dunphy and Bale2011). Fourth, the demands of administration lead to a shift in attention from ideological radicalism towards practical policy delivery: the so-called ‘pothole theory’ of democracy (Berman Reference Berman2008: 6).

However, many populist parties have managed to maintain their radical stance when in office, achieve policy victories and even profit electorally from the experience (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015). Whether moderation of these parties in office also takes place at the local level of government has not hitherto been addressed. The subnational arena has been assumed to be a location through which mainstreaming takes place, without investigation of the specific mechanisms (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016: 21; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2007: 1190). Crucially, in order to assess the radicalism of a local administration through its actions in office, recent studies have shown that partisan influence is also possible at this level of government (Paxton Reference Paxton2019; Weisskircher Reference Weisskircher2019). An analysis of the RN in local government therefore enables us to study a key PRR party that previously had next to no experience of government responsibility, in a context where it is also unconstrained by coalition dynamics.

Dimensions of the mainstreaming of radical parties

Mainstreaming – here used in the sense of radical parties changing to become more like mainstream parties and not the opposite process (see van Spanje Reference Spanje2010) – can take place in a number of ways. First, in terms of de-radicalization of positions taken on the party's core issues: the positions of PRR parties regarding sociocultural issues central to their ideology – primarily immigration, European integration and law and order – are usually far from those of mainstream parties. Second, in terms of an expansion of their programmes beyond certain niches: for the PRR, this niche has traditionally centred on the aforementioned sociocultural issues with a lack of corresponding emphasis on socioeconomic issues (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Third, a softening of anti-establishment positions: populism, from which anti-establishment positions stem, is here defined as: ‘an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 543). The populism of these parties manifests itself in a style of discourse which expresses those ideas (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013), as well as actions that represent a refusal to abide by the formal and informal ‘rules of the game’ (Abedi Reference Abedi2004), whereas mainstreaming results in less populist content in discourse and action. Fourth, their organizational competence and perceived fitness to govern may increase, helping to surmount the concerns of some voters that radical, niche and populist parties do not have the legitimacy to hold government responsibility. A reputation for incompetence in the role has proved an obstacle to further electoral success (Fallend and Heinisch Reference Fallend and Heinisch2016; Heinisch Reference Heinisch2003; Luther Reference Luther2011). These four dimensions of mainstreaming – de-radicalization of issue positions, expansion of programmes, softening of anti-establishment positions, and an increase in focus on the party's competence – therefore provide the grounding for a number of expectations, which the following section will outline for the specific case of the RN in local government.

Expectations of the local Rassemblement National mainstreaming strategy

There can be no doubt that under the influence of the leadership of Marine Le Pen since 2011, the RN has sought to portray itself as a more mainstream party and overcome its reputation for racism and extremism (Crépon Reference Crépon2012). An impressive rise in electoral support also demonstrates a significant degree of mainstreaming in the perception of the electorate (Mayer Reference Mayer and Rydgren2018: 12). Despite eventual defeat in the second round of the 2017 presidential election, Marine Le Pen managed to secure more than 10 million votes, which represents one third of those who voted.Footnote 4 Subnational politics also seem to reveal a wider acceptance of the RN: the 2014 municipal elections represented a significant breakthrough, with an unprecedented 11 mayors elected.

Several barriers to the RN being perceived as a ‘normal party’ by voters remain, which it has sought to address in local government. The first is ideological. The RN continues to be seen by the majority as extreme in its xenophobia and thus a danger to democracy (Mayer Reference Mayer and Rydgren2018: 15). To overcome this reputation, overt racism from party officials has been punished more strictly and publicly, most notably in the case of the expulsion of Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2015. The central opposition to ‘radical Islamism’ and communautarisme has been increasingly framed in the name of democracy, secularism and the defence of minority rights. In contrast to the municipal governments of the Front National in the 1990s that attempted to put in place the nativist ideas of ‘national preference’ (Davies Reference Davies1999; Shields Reference Shields2007), we expect the party to downplay nativism in policy and discourse in the leadership of local government of Hénin-Beaumont since 2014.

Closely connected to the perception of radicalism is the RN's image as a niche party, with a focus confined to issues of immigration and security and much less emphasis on crucial issues such as the economy. A much commented-upon plank of the RN dédiabolisation strategy is a new focus on social issues and areas negatively affected by globalization (Ivaldi Reference Ivaldi2015; Shields Reference Shields2014: 502–503). As a result, we expect the RN-led local government of Hénin-Beaumont to emphasize socioeconomic issues in policy and discourse.

The RN has long been anti-establishment in its extreme opposition not only to mainstream parties but the entire political system and underlying republican values (Ivaldi Reference Ivaldi, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016: 231). A recent innovation of Marine Le Pen is an insistence upon the RN's republicanism and loyalty to the system (Shields Reference Shields2014: 503). In order for such mainstreaming to be evident in this dimension in Hénin-Beaumont, we should see the RN use a less populist style of discourse and abide by the formal and informal ‘rules of the game’ of local government leadership.

A further limitation faced by the RN which it seeks to address at the local level of government is its lack of credibility as a party of government. Due to the French majoritarian electoral system and the continued cordon sanitaire imposed by the mainstream parties at national and regional level, the RN has been unable to gain experience in the same way as many other European PRR parties and in the process develop actual and perceived governing competence. Before 2014, the party's experience of local government and institutional adaptation was limited to ‘those few but significant towns where it exercised municipal power (Toulon, Orange, Marignane and Vitrolles), [in which] it pushed the bounds of constitutionality in seeking to implement its programme’ (Shields Reference Shields2014: 497). Indeed, these examples of the RN in subnational positions of responsibility following its breakthrough in the 1995 municipal elections were beset by tales of incompetence as well as nativist extremism in policy. As a result, we expect the RN leadership of the local government of Hénin-Beaumont to emphasize its competence in the role.

Case selection, data and methods

To investigate the use of local government leadership by RN actors as part of a strategy of mainstreaming, we conducted a case study analysis, paired with a mainstream party-led case from the same region. A paired comparison within the same systemic context provided an analytical baseline with which to assess the distinctiveness of the RN-led case (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2010: 244). We analysed its discourse to test our hypotheses derived from the literature on mainstreaming of PRR parties in general, and the ‘de-demonization’ strategy of the RN in particular, namely: the extent to which the RN de-emphasizes overt ideological (in particular, nativist) commitments and extends to cover wider (in particular socioeconomic) issues in its policy focus, and the extent to which its discourse emphasizes anti-establishment credentials and competence, including through populist and technocratic frames (Caramani Reference Caramani2017).

The case of Hénin-Beaumont, governed by the RN since 2014, was selected as one of the largest towns controlled by the party but also the most symbolic and important – hence its status as the vitrine. Furthermore, given that the mayor, Steeve Briois, is also a national figure for the party, we expected the national party to have an important influence on policy decisions. Nearby Lens, also in the Pas-de-Calais department, was selected for comparison: a similarly sized city that has also experienced an economic downturn associated with the decline of the mining industry. It is led by the Parti Socialiste (PS), the party that governed Hénin Beaumont alone or in coalition with other left parties throughout the post-war period. The discourse of the local governments during the period 2014–19 was analysed via a number of sources. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 12 local government actors from both the governing and opposition parties in Hénin-Beaumont and Lens. Representatives from the governing parties were in positions of responsibility as deputy mayors (adjoints au maire), and opposition actors were elected as local councillors. As the interviews were conducted on condition of anonymity, those interviewed are not identified by name. The interview questions were adapted from the surveys of European mayors conducted by the POLLEADER network with a focus upon the governing process and their policy outputs (Heinelt et al. Reference Heinelt, Magnier, Cabria and Reynaert2018). Articles from the governing period 2014–19 were sourced from the online archives of the most widely read local newspaper, La Voix du Nord, using keyword searches. Additional expert interviews were held with journalists based in the two towns in order to gain further insights free from partisan bias.

Issue positions and salience were assessed using a qualitative content analysis of the local government newsletter, Hénin-Beaumont C'est Vous!. This monthly publication was introduced by the RN administration in order to communicate directly with citizens and bypass the local press, which is claimed to be opposed to them. The newsletter is delivered to all households in the municipality and therefore has a larger potential local audience than any other source. From each of the 46 newsletters coded, the mayoral statement was broken down into 728 core sentences as the unit of analysis. Data were also drawn from the monthly newsletter of the Lens administration, Lens Mag: mayoral statements from 45 newsletters were transformed into 670 core sentences.

Similar to past applications of core sentence analysis, we code the relationship between ‘political objects’ in the text, between a subject (a political actor, in this case the mayor) and an object (either another political actor or a policy issue), along with the direction of the relationship between the two (Kleinnijenhuis et al. Reference Kleinnijenhuis, de Ridder, Rietberg and Roberts1997).Footnote 5 The categorization of policy issues was based upon the framework of Hanspeter Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006), selecting from the following items: budget, local economy, culture, education, security, immigration, infrastructure, health, welfare, participation. In addition, the frames used to define a problem or justify their position were coded (up to three for each core sentence). Framing, to follow Robert Entman (Reference Entman1993: 52), is to ‘select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation’. For issues, we distinguish between cultural, economic and other utilitarian frames, again following the work of Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). Cultural frames may either be traditional-nationalist or multicultural-universalist; economic frames may be social security-investment oriented or free market-neoliberal oriented; and the utilitarian frames are those without additional ideological content. For actors, we coded the frames on an inductive basis in detail and then summarized them in a limited number of abstract categories.

Analysis: the Rassemblement National mainstreaming strategy in Hénin-Beaumont

Hénin-Beaumont has long been central to the strategy of Marine Le Pen to normalize the party. This is evident in her choice of the town as her seat for National Assembly election attempts in 2007, 2012 and 2017 (in the latter case, successfully), as well as gaining a seat on the municipal council in 2008 and 2009. It offers advantages to the party due to its context: a former coal-mining town devastated by socioeconomic problems and a difficult post-industrial transition. Hénin-Beaumont is a potent symbol of the ‘left behind’ of globalization (Crépon Reference Crépon2012; Gougou and Mayer Reference Gougou and Mayer2014). The voters in this social group are crucial to the contemporary populist radical right across Western Europe (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006: 922). As well as profound socioeconomic problems, the RN could capitalize on localized political controversies. The corruption scandal involving the long-governing Socialist-led administration caused it to collapse and the mayor, Gérard Dalongeville, was arrested in 2009. At that point, the long-standing, but gradually eroding, bonds of industrial employment, class solidarity and socialist politics seemed truly shattered. The opportunity was created for gains to be made by the RN, yet the particular context demanded adjustment of the party's programme.Footnote 6 Core issues of immigration and national preference were removed from RN campaigns in Hénin-Beaumont from 2008 onwards (Tondelier Reference Tondelier2017: 50). The apparently moderated RN won the 2014 Hénin-Beaumont municipal election in the first round with 50.25% of the vote and Briois became mayor. Due to the size of the victory, the RN was able to govern alone without the need of coalition partners and the associated constraints that would be imposed.

Policy: de-radicalization of core issue positions and programmatic broadening?

First, what are the policy areas focused upon by the RN administration in Hénin-Beaumont? To what extent and how does the party pursue its strategy of dédiabolisation through its policy? Our analysis draws from interviews with local government actors and the newsletters of the administration to reveal the relative salience of different policy areas and their framing.

The results illustrated in Figure 1 show the predominance of cultural policy, infrastructure works and financial management in the communications of the RN administration of Hénin-Beaumont. First, cultural policy has been made central to the output of the local government: it is the most salient issue, to a greater extent than in Lens. According to interviews with actors from both the governing majority and opposition, the administration has focused strongly on collective gatherings such as festivals and markets.Footnote 7 Its approach is intended to be close to the interests of the local population and RN actors contrast nearby towns run by mainstream parties whose cultural events are ‘pharaonic in terms of budget but of little interest to the population’.Footnote 8 Traditional symbols have been given a new emphasis in public displays during the Christmas season in Hénin-Beaumont. As a result, a public nativity scene has been the focus of a symbolic battle between the administration and opponents (Martin Reference Martin2017). Yet there is an absence of nativist framing of cultural policy, as was strongly in evidence in towns led by the party in the 1990s with ‘partisan choices over artistic events, cinema schedules and library holdings’ (Shields Reference Shields2014: 498).

Figure 1. Policy Issues in Mayoral Statements

Sources: Hénin-Beaumont C'est Vous! (2014–19); Lens Mag (2014–19).

Second, there is an emphasis on infrastructure, particularly the beautification of public spaces.Footnote 9 These works are framed as non-ideological achievements. As an RN local government official states: ‘When we redo a pavement or … a road, the pavement is not left, it is not right, it is not conservative, it is not liberal.’Footnote 10 The changes that are most focused upon in the newsletters are renovations made to the church and town hall. These historical buildings have high symbolic value, recalling an earlier age of prosperity and grandeur, as well as the more recent past of neglect. Opposition councillors were at pains to stress that many of these improvements, including the renovation of the church, had been initiated by the previous administration. Nonetheless, they found that since the election of the RN in 2014 ‘the average resident has the impression that the town is cleaner, more beautiful and has more flowers’.Footnote 11

A repeated claim by the RN administration is that it delivers services better thanks to more effective financial management. Indeed, when presenting its budgetary policy – its third most focused upon issue – the administration emphasizes its financial efficiency and continual lowering of taxation. The budget is presented as an opportunity to ‘right the wrongs’ of the previous administration: to resolve the toxic loans and reduce high taxation that was needed to deal with the resulting debt. The focus of the economic agenda is upon the reduction of taxation: initially by 10% and then by an additional 5% the following year (Farel et al. Reference Farel, Fieschi and Gherdane2015: 241). It has also cut costs through an increase in free market solutions, in contrast to previous deals agreed to with favoured contractors.Footnote 12 There is a lack of associated investment in social issues in Hénin-Beaumont alongside these cutbacks, which contrasts with the idea that the mariniste RN follows a leftist economic agenda (Ivaldi Reference Ivaldi2015).

In sum, through these three policy areas the administration emphasizes improvements made to the day-to-day quality of life for citizens in the town in a manner that is visible and felt in the short term, and contrasts with the previous administration. As Steeve Briois stated prior to the 2014 elections: ‘I will not do things like in Vitrolles. I will leave the domain of ideology and symbols to those who have a good imagination. I want to give life to Hénin-Beaumont, make it a clean and healthy town where people are happy.'Footnote 13 Similarly, a senior RN official we interviewed claimed that ‘running a town is not about politics or ideology, it needs to be run pragmatically. One must be a realist when running local government.’Footnote 14 As James Shields (Reference Shields2014) suggests, the party has learned from the legacy of an ideology-driven approach to local government in the 1990s and our results show that, at least in Hénin-Beaumont, it has managed to distance itself from the more radical elements of its policy agenda and promote organizational competence.

Much less focused upon are two core issues of the RN: security and migration. Despite the apparent de-radicalization of the contemporary RN, these issues are still central to a national party discourse that remains solidly radical right (Ivaldi Reference Ivaldi, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016: 229). Indeed, the two have become more closely intertwined as opposition to Islam/Muslims is framed as a threat to national values and linked to terrorism, rather than earlier notions of explicit racism. In Hénin-Beaumont, the expansion of CCTV security and policing were mentioned in interviews with deputy mayors. However, security policy barely features in the mayoral statements. Furthermore, the issue of migration had no core sentences whatsoever devoted to it throughout the entire period. The only migration-related intervention is the charter issued by a number of RN mayors, including Briois, that opposed the reception of migrants in their towns following the dismantling of the migrant camp in Calais (Front National 2016).Footnote 15 In sum, this suggests more than a simple toning-down of language regarding these issues, as has been attributed to the mariniste RN (Bastow Reference Bastow2018). Rather than de-radicalization in the sense of changing its position, the issues are avoided almost entirely by the RN in Hénin-Beaumont in its communication with citizens.

However, despite this apparent move away from a programmatic niche centred on nativism, the RN has not extended its programmatic focus into socioeconomic issues as expected. Policy proposals to contend with the economic decline of the town were lacking in both the interviews and mayoral statements. The relative absence of broader socioeconomic issues from the RN administration is revealed by comparison with nearby Lens, where issues of economic development, education, healthcare and social assistance are given far more attention in the mayoral statements. The opportunity for French local governments to generate local economic development is constrained as this is a responsibility of the inter-communal body (établissement public de coopération intercommunale – EPCI) that groups several small towns, or higher levels of government, such as the region. The case of Lens shows, however, that various forms of intervention are indeed available to mayors. In contrast, socioeconomic issues are another set of policy areas avoided by the mayor of Hénin-Beaumont in his communication with local citizens.

The policy priorities of the Hénin-Beaumont local government are distinct from those expected from a PRR party such as the RN. Government action is instead focused upon concrete changes to the local environment, in terms of both events and infrastructure, as well as the budget. As the issues that characterize the RN as a distinctively PRR party (immigration and security) are lacking, this represents a clear moderation of its stance in substantive policy terms, although its issue focus remains narrow when it comes to socioeconomic policies (beyond the budget). Furthermore, the framing of these policies is utilitarian, similar to the administration in Lens; there is no evidence of a distinctively ideological framing, in either a cultural or economic sense.

Discourse and style: populist and technocratic?

How are local political relations spoken about by the RN administration? How do they envisage the ideal representative model? This section considers how the RN local government actors construct local political relations through the framing of local citizens, the administration and the opposition.

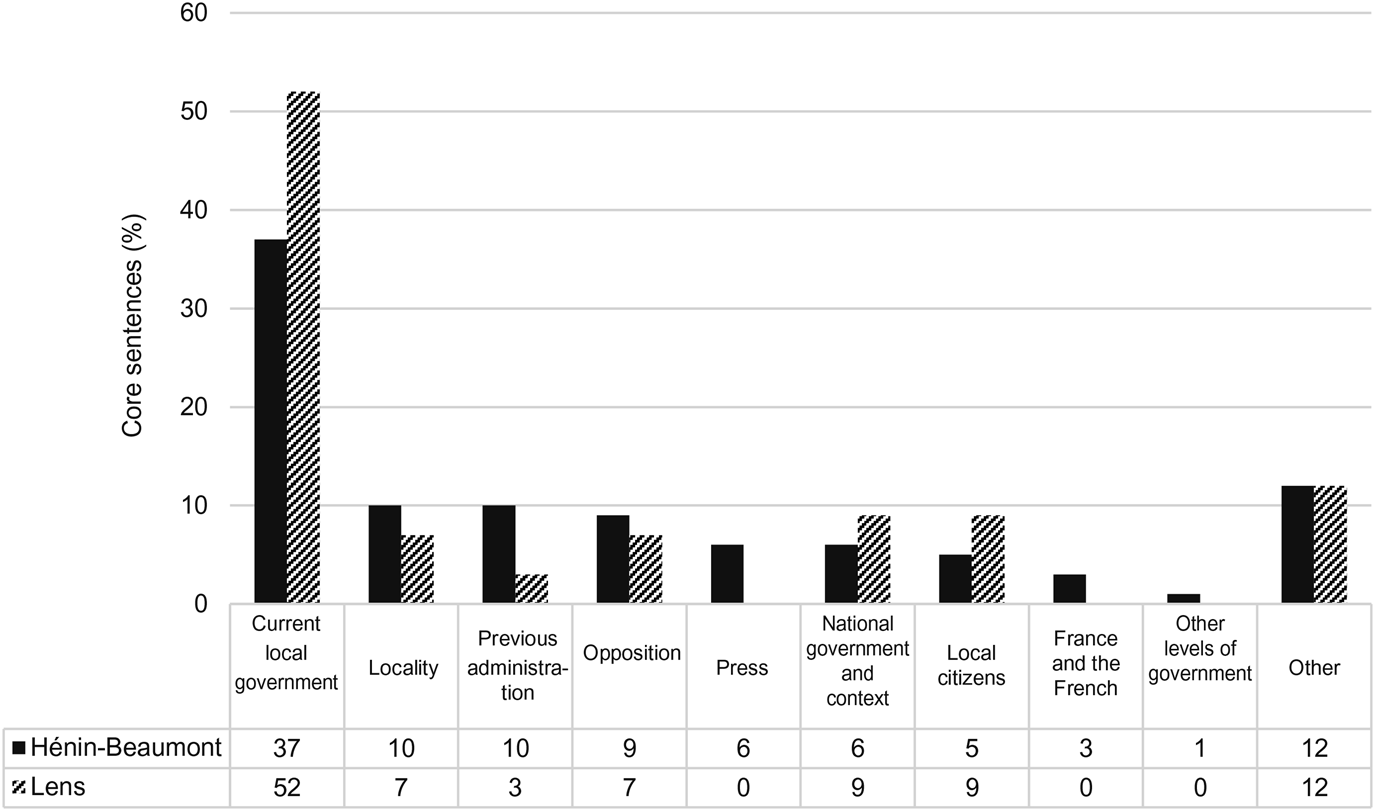

The results shown in Figure 2 demonstrate, first, that ‘the people’ are not a particularly salient topic. This is surprising for a party very well established as populist. According to the ideological definition followed here, people-centrism is a core component. Local citizens are the subject of much less attention than the administration itself and its opposition. Yet, despite the relative scarcity of attention given, the idea of the ‘pure’ people – central to the ideological definition of populism – is evident in the framing of local citizens in terms of dignity, honour and authenticity:

In contrast to [local journalist] Pascal Wallart, who claims that many people in our town ‘no longer have a political conscience’, I think you are pioneers in reappropriating everyday life, reality and the common interest: that's one of the reasons I'm so proud to be your mayor! The dignity and honour of the inhabitants of our town, ridiculed by politicians and the media, are values I want to pay homage to, and which deserve to be defended.Footnote 16

Figure 2. Political Actors per Core Sentence in Mayoral Statements

Sources: Hénin-Beaumont C'est Vous! (2014–19); Lens Mag (2014–19).

The most common framing of ‘the people’ is in terms of their contribution and productivity in efforts to improve the town, for instance: ‘the Heninois and Beaumontois invest great enthusiasm in all municipal projects’.Footnote 17 Furthermore, the populist conception of a homogeneous citizenry is revealed in an interview with an RN local government official: ‘I do not like talking in terms of communities, because in the French spirit, there are no communities, there is a French people, there are no divisions in the French people.’Footnote 18 In this celebration and homogenization of the locality and its population, the concept of ‘the heartland’ is relevant: ‘an idealized conception of the community they serve, [from which] populists construct the “people” as the object of their politics' (Taggart Reference Taggart2004: 274). The homogeneity of the citizenry is also a classic trope of the neo-republicanism that is espoused by parties across the political spectrum in France and thus indicates another form of mainstreaming (Chabal Reference Chabal2015).

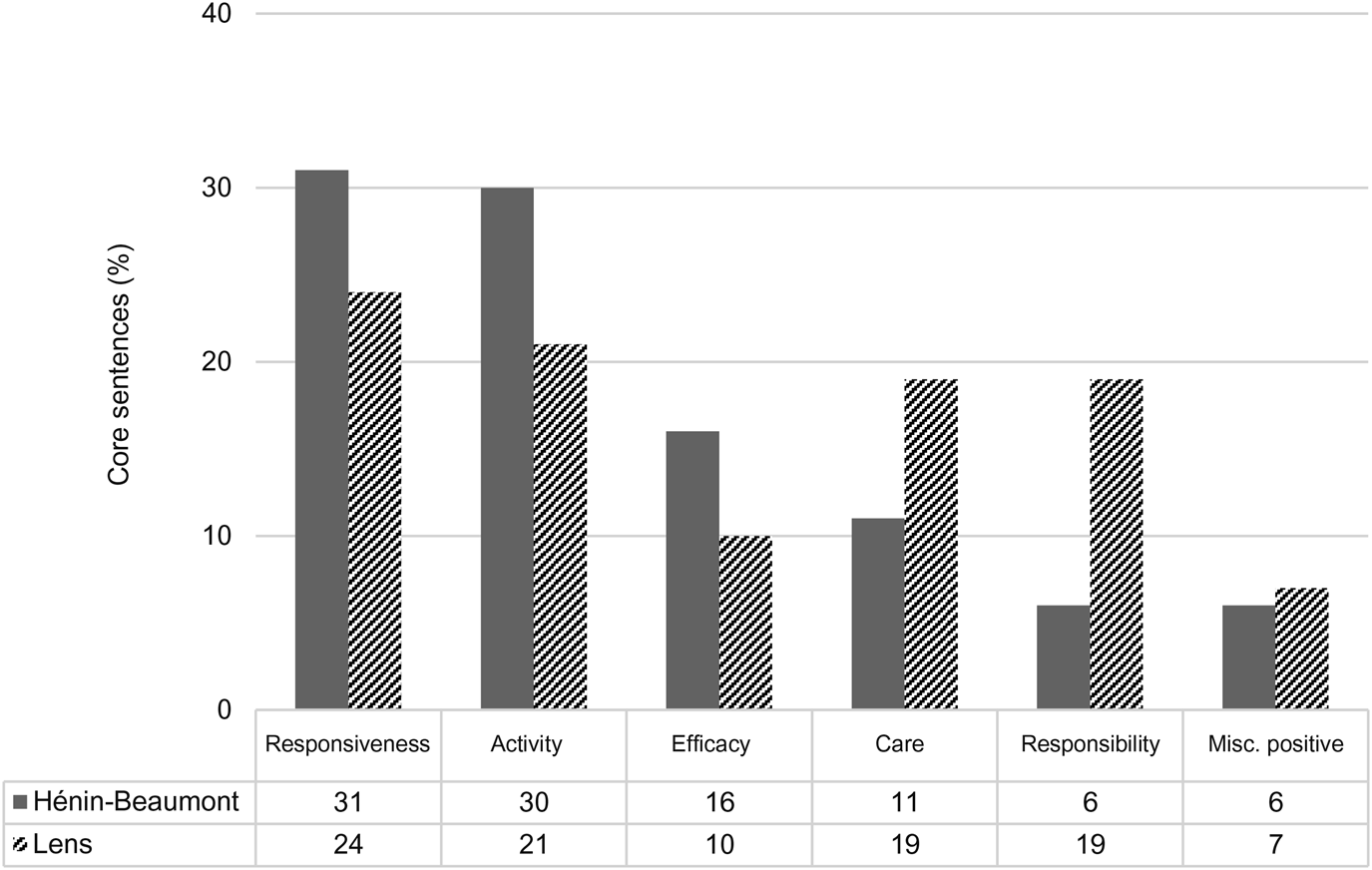

The most referenced actor in the Hénin-Beaumont newsletters is the RN administration itself. The most common framing is in terms of its responsiveness to the demands of the citizens and dedication to its work and efficacy in securing outcomes (see Figure 3). Interviews with leading opposition figures reveal an acknowledgement of the ‘professional’ style of RN elected officials despite opposition to their aims.Footnote 19 The quality of its organization is helped by the seniority of the figures involved in running the town, some of whom are currently serving (or have recently served) as an MEP, deputy of the National Assembly, regional councillor and departmental councillor. Yet, rather than a technocratic emphasis on expertise, the mayoral statements stress their commitment to being close and responsive to local interests.

Figure 3. Framing of Local Government in Mayoral Statements

Sources: Hénin-Beaumont C'est Vous! (2014–19); Lens Mag (2014–19).

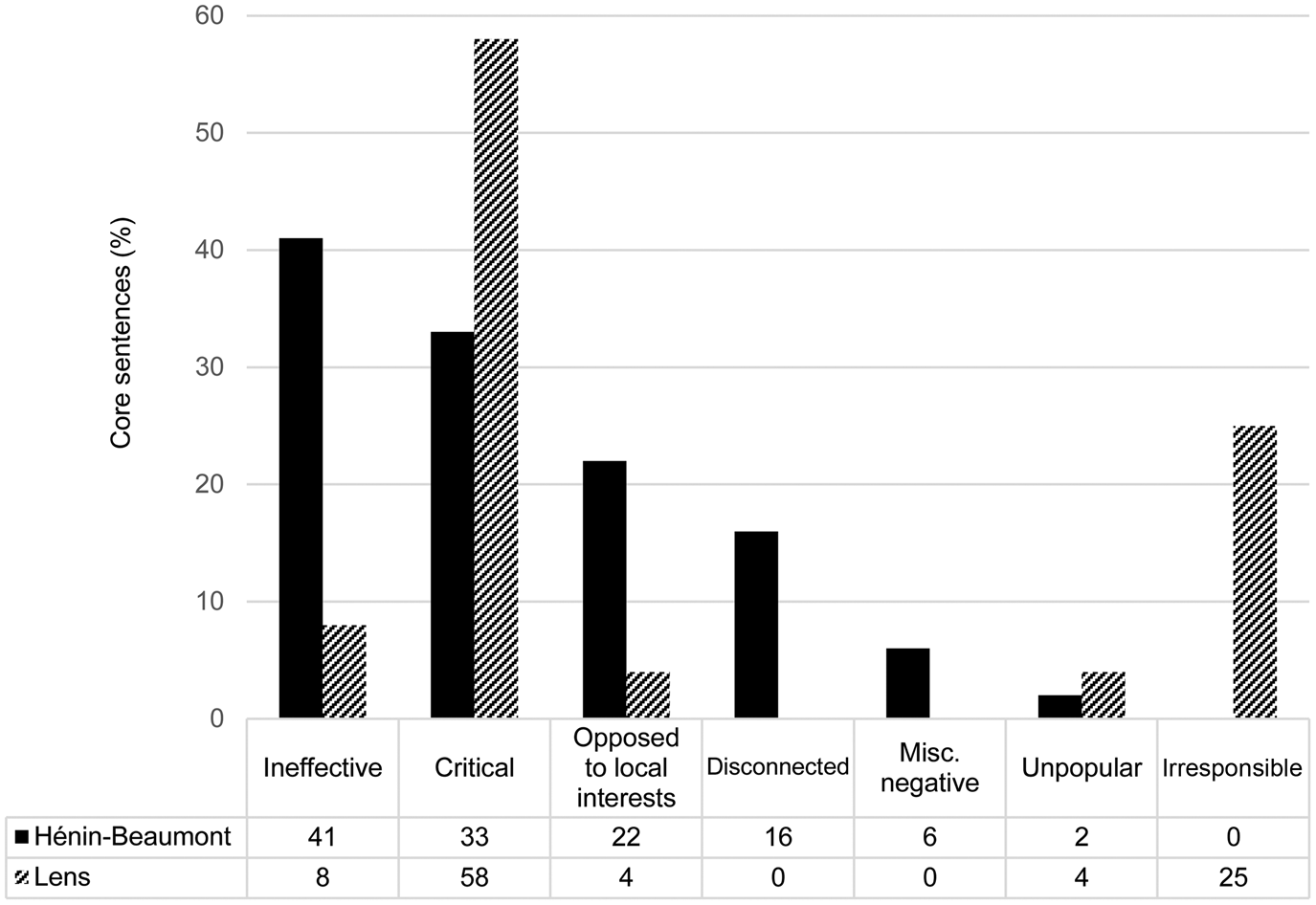

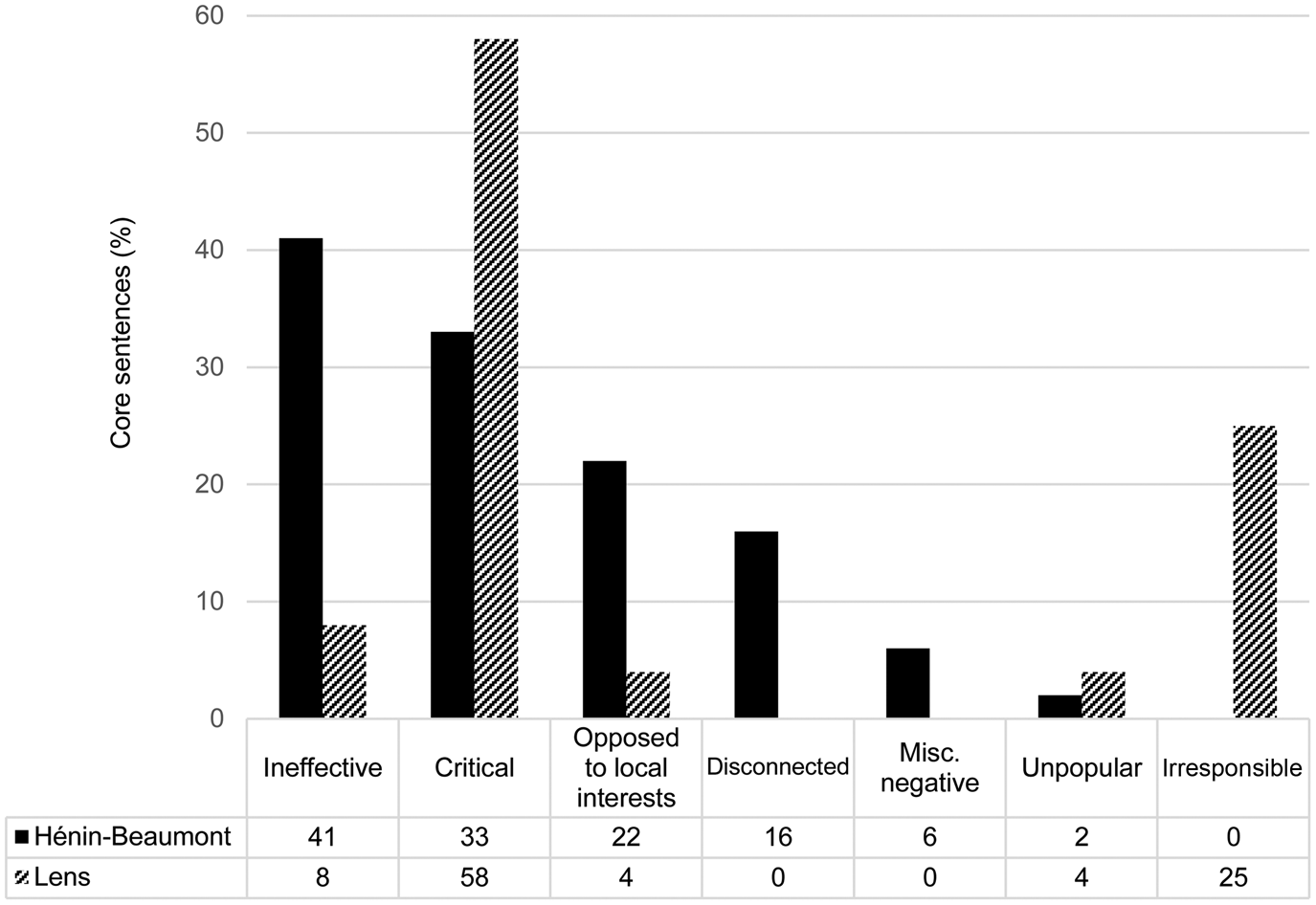

The primary targets of the RN administration – those actors who were most often mentioned negatively in interviews and coded with a negative position in the mayoral statements – are opposition political actors. They are portrayed negatively in terms of their performance above all, with the use of frames of ineffectiveness (see Figure 4). Ideological antagonism is also expressed by the RN through framing of the opposition actors’ supposed hostility to local interests and disconnection from traditional culture. Furthermore, the opposition is represented as overly critical and consequently obstructing the RN administration from getting things done: ‘an opposition that only knows how to criticize what appeals to the inhabitants of our town’.Footnote 20 This latter point is mirrored somewhat in the case of Lens: the administration similarly frames its (RN) opposition as unproductively critical. However, the PS mayor of Lens takes a distinctive stance against the opposition's ‘irresponsibility’, which he juxtaposes with his own ‘responsibility’ (a much more frequently employed self-framing by the Lens mayor – see Figure 3), which is typical of mainstream party ‘anti-populism’ (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2018: 6).

How can we attribute any credibility to those [from the RN] who confuse running a town and a flea market, for whom the art of making promises and telling voters what they want to hear is actually the art of trying to dupe the Lensois? No, frankly, they are visibly lacking in seriousness and competence in their hostile crusade. And their excesses and outbursts, sometimes aimed at me or some of my deputies, render their attacks ludicrously inappropriate or simply pointless.Footnote 21

Figure 4. Framing of Opposition Actors in Mayoral Statements

Note: For Hénin-Beaumont, opposition actors includes the previous administration as well as the current opposition party.

Sources: Hénin-Beaumont C'est Vous! (2014–19) Lens Mag (2014–19).

Another target of the RN administration is the press. The local newspaper, La Voix du Nord, has been vociferously targeted. The conflict between the paper and the administration was focused upon in all interviews and was present in the newsletters. As revealed in interviews with senior RN administration figures, the rift was truly opened up during the campaign prior to the 2015 regional elections when the newspaper, which effectively holds a monopoly in the area, strongly opposed the party (La Voix du Nord 2015a, 2015b).Footnote 22 In the newsletters of the administration, the paper is framed as culturally disconnected from the town, disrespectful to local citizens, frivolous in its favoured issues and polemical in its constant opposition to the RN administration.

They attack me because I defend you. Since 2014, our administration has been the target of all types of attacks: lies, defamation, invasion of privacy, jeopardizing of municipal projects, threats, judicial persecution, and so on. The self-righteous and the media are always less scrupulous when it comes to attacking the governing majority. Against us anything, even the very worst [criticism], is allowed.Footnote 23

There is a notable lack of reference to the non-‘native’, migrant figure as the ‘other’ by the RN in both interviews and mayoral statements. Even local opposition actors admit that relations between the local mosque and the RN administration are positive (Tondelier Reference Tondelier2017: 69). Like the avoidance of policy issues that resonate with traditional RN nativism, social groups that would be excluded according to nativist ideology are similarly avoided in the discourse of the RN administration. Muslims are mentioned just once in the mayoral statements, to justify their Christmas public celebrations – ‘whether one is Catholic, Jewish, Muslim or atheist, one can admire the beauty and innocence of a nativity scene without seeing it as an attack on someone's beliefs’Footnote 24 – and radical Islamism also only once, in response to the 2015 terrorist attacks. To label such discourse as nativism would be an excessive stretch of the concept. The antagonism constructed by the RN in Hénin-Beaumont is instead focused on formal local political relations.

Discussion

How do we explain the approach taken by the RN in Hénin-Beaumont? The predominant and, in comparison with a mainstream-led case, distinctive features of its policy are the salience of cultural events and budgetary stability (without the usual nativism, yet neither with greater socioeconomic breadth). Its discourse is distinctive in the focus on its own competence and responsiveness to public opinion, in contrast to the politicized obstruction of the previously governing centre-left and local media. The strategic emphasis is on the projection of an image of competence in government and closeness to citizens. This is intended to help mainstream the party in the eyes of the electorate. As one official confided, ‘the way we have run the town has helped to de-demonize the RN, no doubt about it’.Footnote 25

Can the approach of the RN administration be characterized as populist? The mariniste RN has been reported to have pursued a ‘discursive shift [that] involved a more developed populism’ (Bastow Reference Bastow2018: 23). The complaint made by RN actors in Hénin-Beaumont is that the town was neglected by the preceding local government, and its claim in response is one of action and thence visible improvements to daily life. The differences expressed in the newsletters between the current RN government and their predecessors are not primarily ideological in nature but of effort and achievement: a feature of valence politics. Yet, the representation of a positive and pure citizenry, whose interests the administration is uniquely able to represent, can certainly be characterized as populist. Furthermore, the behaviour of the RN in Hénin-Beaumont has demonstrated an anti-establishment logic in challenging the ‘rules of the game’. The results show a highly conflictual political environment since the RN has been in office. The council meetings have been particularly confrontational, with personal attacks on opposition politicians both during the meetings and subsequently on social media.Footnote 26 Furthermore, the opposition has been frustrated by the lack of prior communication regarding the scheduling of these meetings. The administration has prioritized control: a further example illustrated by reports of an increase in surveillance of political statements made by municipal staff on social media, in order to prevent continuing links between the town hall and the parties in opposition since 2014 (Tondelier Reference Tondelier2017).

A technocratic governing approach can be used to signal moderation and competence. While some have considered the concepts of populism and technocracy as antithetical to each other (Laclau Reference Laclau2005), other recent works conceive them to be ‘unlikely allies’ (Bickerton and Accetti Reference Bickerton and Accetti2018; Caramani Reference Caramani2017). Above all, both are united in their opposition to (representative) politics, pluralism and bureaucracy. Furthermore, technocracy and populism are particularly well matched at the local level of government due to its typically less party-political character, as well as the more common demand for problem resolution in non-ideological fields. Investigation of whether such technocratic populism is also reflected in the populist radical right has not hitherto been carried out (Bickerton and Accetti Reference Bickerton and Accetti2018: 145). We find the discourse of the RN in Hénin-Beaumont does focus upon its apolitical performance, yet lacks the defining characteristic of technocracy as an apolitical focus on resolution of individual demands by experts (Fischer Reference Fischer1990). Instead, it emphasizes its dedication, responsiveness and proximity to local interests.

Conclusion

The mainstreaming of radical parties as a result of government participation has, up until now, neglected a subnational perspective. As a result, the RN has been excluded from the discussion due to its absence from national and regional power. This article has shifted perspective to the municipal level of government and shown how the RN leadership of the local government of Hénin-Beaumont is de-radicalized, not only in historical comparison to the Jean-Marie Le Pen era of the party, but even in comparison to the national level in the current phase of dédiabolisation. Various scholars of the RN have disputed the extent to which the party has truly undergone moderation in substance rather than appearance, and in which aspects – rhetoric, policies and reputation (Ivaldi Reference Ivaldi, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Surel Reference Surel2019). Indeed, the continuing populism in discourse and style remains in evidence as the party seeks to break the old consensus and form a new local hegemony. We argue that this is a case of strategic mainstreaming in pursuit of respectability and a display of competence rather than moderation imposed upon the party by the responsibilities of governing, as the ‘pothole theory’ would suggest.

The responsibilities of government have certainly not damaged the electoral scores of the party in Hénin-Beaumont. In the 2015 regional elections, the town voted massively for the RN, in some wards up to 72% (Tondelier Reference Tondelier2017: 8), and the results of the 2017 presidential and legislative elections also showed increased support for the party in the town compared with 2012, well beyond the national rate of increase. In March 2020, Steeve Briois was re-elected as mayor in the first round of the municipal election with an impressive 74% of the vote. We therefore emphasize the agency of subnational political actors to implement distinctive strategies and attain atypical levels of electoral success, as argued elsewhere with radical left parties (Weisskircher Reference Weisskircher2019: 148).

The strategy of mainstreaming by radical right parties is a risky one with which populism can help. To moderate ‘too far’, in pursuit of shedding the image of racism and attaining one of mainstream credibility, risks losing the parties’ core support (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Dézé Reference Dézé, Crépon, Dézé and Mayer2015; Ivaldi Reference Ivaldi, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016). This risk is particularly high when these parties enter government positions, due to the need for compromises on top of the strain of responsibility. Populist ideology and communication strategies facilitate a strategic moderation, including when in power; for example, the ‘one foot in, one foot out’ strategy of the Lega Nord in Italy (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2005). In this way, populism is far from incompatible with power, which was the dominant conception in the past (Canovan Reference Canovan1999; Mény and Surel Reference Mény and Surel2002; Taggart Reference Taggart2004: 284), but in fact can contribute to building support in government as well as in opposition. Our study shows this compatibility at the local level of government: here the RN has presented itself as the true representative of ‘the people’ and its opponents as an elite opposed to its interests, in place of a nativist emphasis upon ethnically defined outgroups.

This study opens three main avenues for future research, beyond the focus of this case study. First, our article suggests an understudied variable for research into the subnational roots of the electoral rise of radical right parties: their actions in (specific, heavily mediatized) local government cases. Future studies could inquire into the extent to which the RN mainstreaming strategy executed in the governance of Hénin-Beaumont resonates more widely in France. After all, its rhetoric of local government as a vitrine implies that the showcase will be visible and influential beyond the municipality itself. Second, future comparative studies could investigate the influence of institutional factors for the local mainstreaming strategies of populist radical right parties. Existing research shows the radicalism of these parties’ pursuit of a populist democratic agenda varies according to the level of local government autonomy (Paxton Reference Paxton2019). Do populist radical right parties in countries with higher levels of subnational autonomy than France display greater independence from their central party office and implement more ideological policy? We could expect particularly strong evidence of a multilevel mainstreaming strategy in France due to the centralized party structure of the RN, as well as an established culture of cumul des mandats. Third, regarding the extent of within-national variation of governing strategies by the PRR: Are these findings from the RN in Henin-Beaumont replicated in other municipalities governed by the party? Hénin-Beaumont has received more attention from Marine Le Pen and the party than any other municipality, which may lead to distinctive results. Furthermore, there are stark differences in the electorate of the RN between the north and south of the country, and varied strategic approaches taken by the party in different regions as a result (Ivaldi and Dutozia Reference Ivaldi and Dutozia2018). Future research should therefore consider the within-national variation of the approach to local government of the RN, and other radical right parties, to assess the extent and manner to which the vitrine of local government changes as the audience varies – in terms of its expression of both the ‘host’ radical right ideology and the ‘thin’ populist ideology.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Versions of this paper were presented at the PSA Conference and a PhD workshop organized by the University of Oslo Center for Research on Extremism in 2019. We thank all those who gave us comments and also Emile Chabal, Léonie de Jonge, Hanspeter Kriesi and Sarah de Lange for their valuable feedback. Finally, we are grateful to our interviewees for their time and the insights they provided.