It is an honour to deliver the Leonard Schapiro lecture, especially in Belfast. I am old enough to have known Professor Schapiro from the days of my first appointment at the London School of Economics and Political Science. More surprising than my age is that possession of one of Schapiro's books once got me into potential trouble. In 1978, then a student in England, I returned to Northern Ireland at Christmas by catching the ferry from Stranraer. At the Scottish port, one of my heavy suitcases drew the attention of a detective. I was asked to open it. The two books most visible were Michael Farrell's Northern Ireland: The Orange State and Leonard Schapiro's The Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The detective showed absolutely no interest in The Orange State, presumably unaware that Farrell, now a member of President Michael Higgins's Council of State in Dublin, was then Ireland's most famous Trotskyist, and had been one of the most prominent leaders of the People's Democracy. Instead, the detective focused on Schapiro's book, and gravely enquired whether I was a communist. I laughed, replied negatively, and could not resist observing that Schapiro was no communist. The detective let me board the ferry, and I thought the episode closed, until the boat docked at Larne. As I walked down the gangway I was tapped on the shoulder. The detective had followed me over. Without arresting me, he asked me to accompany him to the local office of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, just beside the docks. There he asked me to open the suitcase again, lifted up Schapiro's book, and pointed at it. The Ulsterman glanced at the open suitcase, looked witheringly at his Scots colleague, and said, ‘For Chrissake, Jock, the man's a student.’ The episode taught me that when young and crossing a border – even a border within a Union – do not have a beard; it also taught me that the titles of books and lectures do not automatically signal their author's views.

The title of this lecture, ‘The Federalization of Iraq and the Break-up of Sudan’, may be rephrased as the question, ‘Why has Sudan broken up, whereas Iraq may remain intact?’ The question matters because the survival of Iraq's federation matters, and not just because of whatever views one holds on US foreign policy. The break-up of Sudan, currently in incomplete and messy progress, also matters, and not just for the peoples directly affected, but for federalists and secessionists everywhere. First, however, I must explain why I am addressing these questions. The arguments here did not originate in methodological design. I have lived in Sudan because my father worked there for the United Nations (1969–76). I have also spent a significant amount of time in Iraq. In the spring of 2004 I advised the Kurdistan Region during the making of the Transitional Administrative Law of Iraq, and again during the making of Iraq's Constitution in the summer of 2005.Footnote 2 Related advisory work continued intermittently until spring 2009, when I became the senior adviser on power-sharing to the Standby Team of the Mediation Support Unit of the United Nations. During my UN secondment I had two Sudanese engagements. In one I was loaned to Chatham House to facilitate dialogue between the Sudanese People's Liberation Movement (SPLM), which had run the government of South Sudan since the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2005, and the National Congress Party (NCP), which had been in power in Khartoum, alone or in coalition, in disguise or in the open, albeit with a name change, since the coup d'état led by Omar Hassan Ahmed al-Bashir in 1989. One of my tasks was to make impartial presentations in Juba and Khartoum on how power-sharing might be organized to make unity more attractive – one of the options on which the South Sudanese were scheduled to vote in a referendum in January 2011. Another task was to address how peaceful secessions work – the other option in the referendum. In December 2009 I participated with some of the same politicians and their officials in a three-day seminar organized in South Africa to craft realistic scenarios for what Sudan would be like after January 2011. We discussed boundaries, security, the ownership of natural resources, including oil and water, citizenship rights, nomads and settled farmers, and public debt – the issues that still animate the governments and armed forces of Sudan and South Sudan. My second engagement, in 2010, took me to Doha, Qatar, where the African Union, the UN and the government of Qatar were mediating another peace process between the government of Sudan and rebel movements from Darfur: my task was to assist in the drafting of power-sharing proposals regarding the Darfur region, the States of Darfur, and arrangements within Sudan's federal government.

These engagements inspired my question, not a formal political science agenda, yet what follows is influenced by my academic field. Having worked with Kurdistan's leaders when they wanted to make Iraq a workable federation, I was impressed by their decision not to press their claims to a formal right of secession, even though Iraq has brought Kurdish people a history of coercive assimilation, territorial gerrymandering, ethnic expulsions and partial genocide. Why did Kurdish leaders not behave as a range of organizations and persons, including the International Crisis Group, still suggest they are really behaving? Why are their leaders not overt secessionists? Why have they not behaved more like the South Sudanese in these last seven years? Having worked with the UN to encourage North–South negotiations, and within the negotiations over Darfur, I was equally impressed by the apparent determination of the Khartoum regime not to do what was required to hold its state together. Its leaders mostly seemed to prefer ‘downsizing’ to further constitutional or power-sharing concessions, at least to the South. Why? Conversely, why were so few South Sudanese willing to pursue the conviction of their late leader John Garang that unity could be made attractive?

LONG-RUN PARALLELS

Let me first observe six remarkable long-term parallels in the histories of Sudan and Iraq that have not, to my knowledge, been systematically noticed before. They serve to show the compelling reasons why both the Kurds and the South Sudanese should have been equally ardent secessionists in the decade that has just passed.

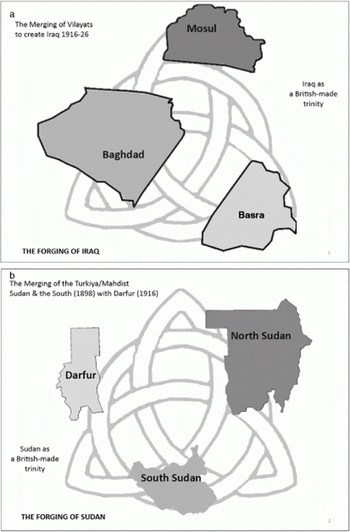

1. Sudan and Iraq are both post-colonial states with common imperial formations and heritages; in each case three historically distinct entities were coerced into precarious unities by British imperialist successors to the Ottomans.

The places that became Iraq and Sudan were subjected to both Ottoman and British imperialism, with the important caveat that the British and the Ottomans, later the Egyptians, allegedly co-governed the Sudan in a condominium (1898–1956) that has no parallel in the history of Iraq. It was, however, a distinction without a significant difference, because British governor-generals administered Sudan with British military officers and colonial district officers; Egyptians served mostly as the infantry.Footnote 3

Modern Iraq was invented by the British conquerors of the First World War, who combined the Ottoman vilayats of Basra, Baghdad and Mosul, which had never before been governed as one jurisdiction. Modern Sudan was created though Kitchener's conquest of the Mahdist state in 1898, and the subsequent conquest of the Darfur sultanate in 1916. Sudan's formation, however, is more like Iraq's than is often realized, because it too is a British-manufactured trinity (see Figure 1). Its first component was the core of the brief Mahdist state, itself built on Turkish/Ottoman Nubia, in turn built on the demesne of the Funj or Sennar sultanate.Footnote 4 Its second, South Sudan, was partially conquered very late in the ‘Turkiyya’, and fully re-conquered by the British after 1904.Footnote 5 Sudan's third part, Darfur, was added during the First World War after Sultan Ali Dinar's unwise decision to join the war as an ally of the Germans.Footnote 6

Figure 1 Iraq and Sudan as British-manufactured Trinities

To baptize these new ‘three-in-one’ entities the British used old Arabic names, but inaccurately. Among the medieval Arab geographers, al-Iraq al-Arabi described what is now Shiite-dominated southern Iraq, the Ottoman vilayat of Basra. Al-Jazeera referred to what is now central and central north-western Iraq, later partially absorbed in Baghdad vilayat: today much of it is known with loose respect for geometry as ‘the Sunni Arab triangle’. Kurdistan was Kurdistan until the late Ottoman reformers partitioned it, and incorporated its southern portion into Mosul vilayat.Footnote 7 In short, the British used Iraq – an old name of part of the future state – for the entirety of the new entity, to the permanent irritation of the Kurds. Their imperial purpose was to unify the Arabs of Iraq against the Turks.

Whereas the original uses of Iraq specified a more restricted space than its current borders, the British used the Arabic word Sudan, from Bilad al-Sudan, or ‘Land of the Blacks’, far more narrowly than in its original usage, to demarcate what became Sudan from Egypt. ‘Sudan’ was a medieval Arab geographers' term for the belt of ‘Black Africa’ beneath Arab-majority north Africa, i.e. for the wide swathe of sub-Saharan Africa from the west to the east coast of the continent (Senegal and Ethiopia were encompassed). Different speakers used Sudan for subsets of this space: the Egyptians and the British used it for the eastern territories, while today's Mali was called Soudan by French imperialists.Footnote 8 The original extension did not encompass many ethnic groups now called ‘Sudanese’. Northern Arabs initially used Sudani, meaning ‘black’, in a derogatory fashion to refer to allegedly inferior, non-Muslim, southern peoples, i.e. the enslaveable. Sudanese nationalists, however, later subverted Sudanese, embraced the concept, and made Sudan stand for a larger entity that included all Northern Sudanese.

Iraq and Sudan later saw some joint investment in the new national ideas embedded in their colonial and post-independence names. Arabs, Sunni or Shiite Muslim, or Christian, secularized or otherwise, came to share an Iraqi identity, though they may have differed deeply on all else that matters in politics. More strikingly, the Northern and Southern Sudanese, though undergoing divorce, will both retain the names of Sudan and Sudanese. The secessionist state, however, has had to concede the right of the title to the name to the rump, according to precedents in international law.Footnote 9 That is why the world's newest state is called the Republic of South Sudan.

In neither Iraq nor Sudan was allegiance to the state or its professedly national identity ever uniform or ubiquitous, and both became spectacular examples of state- and nation-building failures. Darfur resembles Kurdistan in some respects because it was predominantly but not exclusively Muslim on incorporation into the British Empire. Historically religiously syncretic and tolerant, both Darfur and Kurdistan had prior sultanates or principalities, and in each case they were the last of the three historical territories brought into the new British manufactured composite. Identification with the original place-name remained very strong for the largest ethnic group in these cases: Kurdistan means a place abounding in Kurds; and Dar-Fur means the land of the Fur.Footnote 10 It is not important here to decide, as if it were easy, whether the Kurds or the Fur were historically one or many; what matters is that Kurds and the Fur remained culturally and linguistically distinct from the largest Arab-speaking group (as did many other minorities in both countries and in these regions). Darfur had been conquered in 1872 by a slave-trading adventurer at the end of the Ottoman Turkiyya, (1821–84), but regained its independence from the Mahdist state, until conquered by the British in the First World War. Ottoman and British ‘pacification’ of the Kurds was an unfinished business when Iraq became independent. Kurdistan, DarfurFootnote 11 and South Sudan retained their local languages and customs and, through indirect colonial rule, some of their traditional elites survived into modernity. Indeed, landed aristocracies emerged or were made from previously tribal leaders.

In the twentieth century neither Iraq nor Sudan accomplished the collective amnesia that Ernest Renan thought necessary for nation-building.Footnote 12 That is not just because people are still dying today who were born in autonomous Darfur, or in Mosul vilayat, before Sudan and Iraq took their recent shapes. The failure to create inclusive, complementary and forward-looking Sudanese or Iraqi national identities reflects far more than insufficient time, and was overdetermined.

2. Iraq and Sudan are both post-colonial majority Arabic-speaking states at the outer extremities of the Arab-majority world.

In any ethnographic description, at its northern and eastern extremities al-Iraq al-Arabi, Arab Iraq, fades into places dominated by Kurdish, Turkish and Iranian cultures and peoples. To its immediate north, Muslim Arab Iraq overlooks a range of religious and minority micro-nationalities among what are now called ‘the disputed territories’, notably Assyrian, Chaldean and Syriac Christians, and Sunni and Shiite Turkomen. Being proud, situated at linguistic, ethnic and sectarian frontiers, and fearful of acculturation may lead a group to redouble its commitments to its own identifications. Nationalists at the centre of post-colonial Iraq determined to make an Iraqi nation through Arabization, at least in language, and indeed to take Iraq into a wider ‘pan-Arab’ nation.Footnote 13 In the Baathist dream, full unification of all Arab (or Arabic-speaking?) lands was envisaged.Footnote 14 Neither the pan-Arabist nor the Iraqi national formula had any place for Kurds, unless they ceased to be Kurds, or were left aside with anomalous and asymmetric autonomy. Sunni Arabs were especially tempted by pan-Arabism because the rest of the Arab and Arabic-speaking world is predominantly Sunni Muslim. Shiite Arabs, by contrast, were much more disposed towards an Iraq-first or an Iraq-alone identity: sharing Shiite Islam with their eastern neighbours did not make them Persians.

Colonial Sudan's south-eastern, southern and western extremities faded into non-Arab, non-Arabic-speaking, Christian and polytheist Africa. Here too Sunni Arab leaders displayed arrogant insecurities when they came to power after independence. North Sudan's ‘Arab’ as opposed to ‘Arabized’ status remains a live historical and political question. Are Arabized Nubians Arabs? That is, are Sudan's self-defined Arabs of Arabian ethnic stock?Footnote 15 That the North has been distinctly and mostly Arabic speaking for several centuries no one denies, though Sudanese Arabic is said to be ‘creolized’, and ‘Juba Arabic’ is a separate vernacular. Predominantly Islamized and Arabized northern Sudan was certainly distinct from the uniformly non-Muslim South in 1956, when Sudan became independent. Many Sudanese nationalists blamed British imperial strategy, codified in the Closed Districts Order of 1922, for sealing off South Sudan from Islamic evangelism, and from the Arabic language.Footnote 16 The parliamentary and military rulers of post-colonial Sudan tried to rectify what they saw as the British artificial blockage of progress through Arabization and Islamization. These programmes, however, met unexpected but profound resistance. Cultural and ethnic Arabization, emanating from the North, even failed to absorb all Darfuri Muslims as co-nationals, though Arabic is the language of educated Darfuris; many of the diverse peoples of the Nuba mountains also resisted Arabization and Islamization.

‘Arab Muslims’ constituted majorities according to census evidence in both Sudan and Iraq, but they were internally disunited. The Northern Muslims of Sudan have had infamous intra-Sunni (including intra-Sufi) sectarian divisions, though never yet as violently deep as those between Sunnis and Shiites in Iraq.Footnote 17 The respective ethnic majorities of both Iraq and Sudan states confronted territorially concentrated minorities, with histories either of autonomy, or of aspirations to sovereignty, notably in Kurdistan, South Sudan – and Darfur. Centralists intermittently tried to homogenize these peripheries – they said, ‘develop’, ‘modernize’, or ‘civilize’ – often under the influence of pan-Arabist doctrine. The Arabist centralizers had Islamicists, Islamists, and pan-Islamists among their ranks, or as their critical supporters, or as their successors. These centralists faced continuous resistance from at least one-fifth of the population: in Iraq from the valleys, plains and mountains of Kurdistan, and in Sudan from beneath the Sudd. In their most capacious definitions, the Kurdistan region and South Sudan encompassed nearly a third of the relevant host's habitable land. Since 2003 both Sudan and Iraq have faced fresh armed resistance, but from within a different fifth of their populations: from the non-Arabized of Darfur in Sudan, and from the central Sunni Arab triangle in Iraq, whose elites had recently been displaced from power. That introduces another parallel.

3. From independence until 2005 both states were dominated at elite level by a group from one ethnic group from one part of the country.

The founders of the Justice and Equality Movement's Black Book, published in 2000,Footnote 18 used official Sudanese sources to show what all knew, namely, that after independence the country had been dominated, especially in its public sector, by people from three northern riverain tribes, the Shaygiyya, the Ja'aliyan, and Danagla, representing less than 5.5 per cent of the population. They have dominated presidential and ministerial offices and lower-tier official positions, and ensured that resource allocation disproportionally favoured part of the North, at the expense of the rest of the country – including Darfur and the west, and the east, not just the South.Footnote 19 Some detect the shadow of ancient Nubia behind this dominance.Footnote 20

Hanna Batatu, in work first published in 1978, showed the extent to which Sunni Arabs, concentrated in the centre, west and west-north-west of Iraq, dominated the army, the political class, senior officialdom and the landowner class from the formation of the British mandate in 1920. The ascendancy of Sunni Arabs partly flowed from an original network of ex-Ottoman military officers, who came to power with the British-sponsored Hashemite monarchy.Footnote 21 Subsequently, of the 15 members of the Baathist Revolutionary Command Council between 1968 and 1979, 14 were Sunni Arabs; the other, carefully footnoted Batatu, was an ‘Arabized Kurd’.Footnote 22 The ascendancy of the Baathists after 1968, first under Hasan al-Bakr, and then under Saddam Hussein, reorientated dominance within the Sunni Arabs of Iraq, bringing the ‘country cousins’ from Tikrit into a pre-eminence rather like that of the three Sudanese riverine tribes, and eventually led to an almost risible patrimonialism among Saddam's immediate relations.Footnote 23 Nominally the Baath were secular and inclusive, but over time, direct and indirect discrimination against Kurds and Shiite Arabs deepened. When the Baathists' secular commitments were more than nominal, some Christian Arabs were incorporated in the dominant power elite.

4. The two countries had similar political trajectories after the Egyptian revolution that brought Nasser to power: authoritarian nationalism, state socialism, petro-statism, centralization, militarism and civil wars.

Swept up in the enthusiasms of Nasserism,Footnote 24 Iraq and Sudan were deeply influenced by republican Arab nationalism, as a programme for government, and as a mentality that encouraged the coercive nationalizing of minorities. Both countries developed strong pan-Arabist orientations in foreign policy, notably in their support for Palestine, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and later for Marxist and then Islamist Palestinian insurgents. Yet they were pragmatic towards the Arab monarchies, and took Saudi money, investments and mosques when expedient, and fought domestic and foreign wars with Saudi resources. Both countries' Arabists were torn between doing what was required to build their states as nation-states, and their wider orientation towards the Arab world. They were influenced by, yet deeply wary and jealous of, Nasser's Egypt. Sudan's northern Arabs in the Umma Party had sought Sudan's independence early in opposition to Egypt's project for ‘unity of the Nile valley’, though the Unionist Party, as its name suggests, had aspired to an Arabized Nile. Iraq's Baathists supported union with Egypt and Syria, and put this aspiration on the Iraqi flag. Yet al-Bakr and Saddam pointedly avoided delivering the cherished unification. Sudan's Socialist Union similarly foresaw unity with Egypt and Libya, but by the 1980s both the Sudanese and Iraqi regimes regarded Egypt as having betrayed pan-Arabism to the Zionists, and Sudan and Libya were frequently at war through proxies in Chad and Darfur.

Both countries followed the Egyptian template of free officer movements. General Abdul Karim Qasim overthrew the Iraqi monarchy in a bloody coup d'état in July 1958, as the head of a Free Officers Movement. Colonel Gaafar Muhammad al-Numairi came to power in May 1969 in a peaceful coup d'état, also leading a Free Officers Movement. Some of his officer training had been in Egypt. The wily Numairi outmanoeuvred Sudan's Mahdists and communists, and proved more ruthless than they had been when they had chances to remove him. He crushed the Ansar of the Mahdists, created a one-party state under the Sudan Socialist Union, negotiated autonomy with the South, and initially proclaimed a secular state. He remained in power until 1985, constantly reinventing himself and his regime first as socialist and then capitalist, first as pro-Soviet and then pro-American, first as secular and then as the divine instrument of sharia law – sketching himself as a Sunni imam version of a grand ayatollah, yet without any of the preparatory credentials in Islamic law. His remarkable about-turns bear comparison with Saddam's later oscillations between 1991 and 2003. Both men had proclaimed themselves secular, turned on their domestic communists and Islamists, and then declared themselves Islamists when their regimes were endangered.

Qasim had neither Numairi's political antennae, nor his ruthlessness; he sentenced to death those who conspired against him, but did not execute them. Nor did Qasim have Numairi's amazing good luck. He died in a hail of bullets. Numairi, having been deposed, was allowed to return from exile, entertain the idea of running for office, and to die in his bed in Khartoum. In 1968 Hasan al-Bakr was more like Numairi, a nationalist soldier who largely created an authoritarian socialist party from office. Al-Bakr's Baathists, like Numairi, made tactical alliances with communists, and strategic alliances with the Soviet Union, only later to switch Cold War alliances – Numairi more completely. Numairi and the early Baathists were also state socialists, with the emphasis on the state component, socializing domestic and foreign private enterprises. Later Numairi and his Islamist successors, and the Baathists under Saddam, embraced privatization with the zeal of converts, or corrupters.

Both Iraq and Sudan became petro-states, facilitating authoritarianism and corruption, and their governments exploited their revenues to increase rather than reduce ethnic and religious antagonisms. This coincidence is not an endorsement of the strong version of the ‘resource–curse’ thesis, which asserts direct causation between natural resources-based revenues and the absence of democracy, and directly links ‘lootable resources’ to civil wars.Footnote 25 Iraq was authoritarian, indeed a landlords' regime, before its oil wealth came significantly on-stream, and patrimonial modes of corruption and patronage were inscribed in its formation.Footnote 26 At independence in 1932, Iraq was already under the de facto control of army officers and a minority of Sunni Arabs, who would neglect the interests of Kurds and Shiite Arabs, and at worst deliberately exclude them from patronage and equal citizenship. The pre-eminence and political interventionism of the military under the Hashemite monarchy, carrying out coups between 1936 and 1941, as well as the bloody execution of the royal family by the Free Officers in 1958, owed more to Arab nationalism than it did to Iraqi oil wealth.Footnote 27 Though in 1956 Sudan was perhaps better prepared than Iraq for democratic government at its independence – at least in the North – it too quickly became authoritarian. Long periods of military rule were punctuated by very brief parliamentary interludes (1956–58, 1964–65, and, on a very generous coding, since 2010). Authoritarianism manifested itself long before Sudan's oil wealth was known, or fully developed; oil has only flowed for export since 1999.

In both countries the first armed conflict between the major estranged periphery and the centre preceded extensive knowledge of the scale of oil deposits – in Kurdistan in the 1920s, and in South Sudan in the 1950s. The peripheries initiated revolt because their leaders rejected the new state that excluded them, not because they initially hoped to head petro-states in their own right. In both cases Arab and British politicians misled the periphery about their prospects of autonomy or of federal status before independence was official. In any case, oil infrastructure and pipelines are not very lootable, and following the historical record is a better guide to causality in conflict than Paul Collier's regressions. In both cases, the political centres became additionally motivated to keep these peripheral zones within their ownership and control after they appreciated the significance of their major oil deposits. That explains why successive Baghdad regimes were determined to deny the Kurds control over Kirkuk governorate and city, and why successive Khartoum regimes denied the South control over its oil resources, and tried to prevent the return of Abyei to the South (from which the British had removed it after 1905). These motivations help explain why Iraqi and Sudanese regimes orchestrated ethnic expulsions in oil-rich regions, and why they seek to minimize the territories of Kurdistan and South Sudan.

Their colonial heritages, over-inflated militaries and preferences for state socialist development projects led both countries to hyper-centralize within their cores. Khartoum, Omdurman and Khartoum North have merged as a megalopolis, surrounded by a ‘black satellite belt’, largely comprising refugees from Sudan's internal wars. The CIA World Fact Book reports Khartoum city as having just over 5 million of Sudan's over 40 million people; it reports Baghdad city as having 5.75 of Iraq's 30.3 million people. Another measure of population centralization is the state level in Sudan or the governorate level in Iraq. In the 1990s Sudan was Africa's largest country until the secession of the South, and then sized at over a quarter of the area of the United States; it was estimated that up to two-thirds of Sudan's population lived within 300 kilometres of Khartoum, while the 2008 census reported over 7 million people within Khartoum State. The greater Khartoum area therefore encompasses nearly a fifth of Sudan's population. Baghdad governorate, despite the Sunni and Shiite Arab civil war, encompasses about one-quarter of Iraq's.

Alongside Kitchener's conquest of Sudan in 1898 rode a young journalist who wrote in the spirit of Gibbon, Montesquieu and the theory of Oriental despotism:

The degree may vary with time and place, but the political supremacy of an army always leads to the formation of a great centralized capital, to the consequent impoverishment of the provinces, to the degradation of the peaceful inhabitants through oppression and want, to the ruin of commerce, the decay of learning, and the ultimate demoralization even of the military order through overbearing pride and sensual indulgence.Footnote 28

Winston Churchill was describing the Ottoman and Mahdist worlds, but his description serves just as well for Iraq and Sudan in recent times. The exceptions to centralization, namely, the autonomy pacts with Kurdistan and South Sudan, and Numairi's brief experiments with administrative decentralization, proved short lived.

Unsurprisingly, both Sudan and Iraq became deeply repressive, towards both ideological and ethnic minorities. Partly in consequence they have had among the longest wars between centre and periphery in the annals of post-colonialism. The Anya-Nya guerrilla organization fought the North from Sudan's independence in 1956 until 1972, building on the mutiny of the Equatoria Corps in 1955. From 1983 until 2002 the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) fought successive Khartoum governments, led by Colonel John Garang. North–South war filled most years between 1956 and 2011, and the period since 2002 may be read as an armed truce, tempered by violations. In the North–South wars, the highest estimated human death-toll from combat, collateral damage, war crimes, and war-induced famine and disease reaches 2 million.Footnote 29 After 1963 Darfur was the site of a 30-year cross-border and inter-regime war of bewildering complexity, involving Libya and Chad and Darfur-based organizations and proxies, a war about which internationals cared little, and for which there seem to be no reliable death-estimates.Footnote 30 Since 2003 Darfur has often been aflame. In the Anglophone world, and according to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), that is because the Khartoum regime has deliberately deployed its army and encouraged nomadic Arab militias in a racist and partially genocidal war against the Fur, the Zhagawa and the Masalit.Footnote 31 The Khartoum government, by contrast, argues that it is engaged in a counter-insurgency war of state preservation against terrorists with foreign sponsors, and that the current Darfur conflict was originally a version of the age-old conflict between nomads and settled farmers, now aggravated by climate change.Footnote 32 Khartoum's reported death-toll of 10,000 is much lower than the UN's estimate of 300,000. A minority of scholars and credible legal advocates and policymakers have debated the veracity of the charge of genocide,Footnote 33 but no one credible denies extensive war crimes and crimes against humanity. The internal wars in and around Darfur and the North–South wars are, however, merely the biggest wars in Sudan's modern history. A full picture would recount the conflicts in the early 1990s within the Nuba mountains and Blue Nile state, the insurrection led by the Beja Congress in Eastern Sudan after 2005, and the current rebellions in south Kordofan and Blue Nile.

Under the Baathists Iraq too had an almost unbroken record of repression and internal wars on a horrendous scale, though it is unfair to the Baathists to imply there was no previous history of armed antagonism in republican or monarchical Iraq. Masoud Barzani, the current president of the Kurdistan Region, in his memoir of his father Mustafa Barzani, recounts two ‘Barzan revolts’ in Iraq in 1931–32 and 1943–45.Footnote 34 After providing the military leadership of the Mahabad Republic in Iranian Kurdistan, Mustafa Barzani and his mostly Barzan Kurds went into exile in the Soviet Union, but returned to Iraq after the overthrow of the monarchy in 1958, and resumed conflict with Baghdad governments in 1961. Leaving brief truces, briefer negotiations and a short-run autonomy agreement dishonoured by the Baath to one side, General Barzani spent the rest of his life leading the Peshmerga against Baghdad armies. In the end he was defeated by the sudden collective reversal of US, Iranian and Israeli support in 1975, and his mistaken decision not to return to guerrilla warfare. After his death in Washington in 1979 his sons assumed the leadership of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), and – together with a rival organization, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, led by Jalal Talabani – intermittently fought Saddam's regime, with and without Iranian support until 1992. The price paid by the Kurdish people was extremely high. Extraordinary repression, brutal Arabization, coercive displacement, the bulldozing of nearly 4,000 Kurdish villages, the forced urbanization and mass incarceration of Kurdish civilians in detention centres, the deployment of chemical weapons, notably in Halabja, all succeeded one another in escalating horror. The genocidal Anfal campaign climaxed the repression: the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) estimates 182,000 men, women and children were killed.Footnote 35 The defeat of Saddam Hussein in the First Gulf War did not immediately relieve the misery of the Kurds. They paid for their US-encouraged revolt by being assaulted by Saddam's helicopter gunships. A mass exodus to Turkey and Iran was only reversed after the implementation of no-fly zones by guilt-ridden administrations in the USA, the UK and France. Baathist-organized mass repression of the Shiite Arabs was even more ferocious in 1991. Up to 300,000 Shiites may have perished in the repression of their intifada; Marion Farouk-Sluglett and Peter Sluglett estimated that nearly the same number perished in the assaults on the lands of the Marsh Arabs and the southern governorates in the late 1990s.Footnote 36

5. Regimes in both countries have been geopolitically insecure and have aggravated their ‘bad neighbourhoods’.

Sudan had nine neighbours until 2011 (Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Libya and Uganda), whereas Iraq has six (Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Turkey). These neighbours mostly have bleak records, at least regarding their democratic credentials. Neither Iraq nor Sudan is likely to benefit soon from the hypotheses of democratic peace theory, though for Sudan, Kenya, Egypt and Tanzania now show some democratic promise, as do Turkey and Jordan among Iraq's neighbours. In both Iraq and Sudan, insurgencies and coup attempts were externally aided, often with bases, as well as arms and funds. Libya, Uganda, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Chad at various junctures supported either the South Sudanese rebels or Arab militias. Iran has supported Kurdish and Shiite rebels, while Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Syria recently turned blind eyes to the passage of Sunni jihadists. Turkey has two military bases in Kurdistan of doubtful legality, and periodically pursues its own domestic counter-insurgency through attacks on the dwindling platoons of the Kurdish guerrilla force of the PKK (the Party of Kurdistan's Workers), who have bases in the inaccessible Qandil mountains.

Sudan and Iraq were sinners internationally as well as being sinned against. Both interfered in their neighbours' politics. Under al-Turbi's influence in the 1990s the Khartoum regime sponsored al-Qaeda and Pan-Islamist Congresses – called the terrorists' ‘Davos in the desert’. Those close to Turabi tried to assassinate Hosni Mubarak in Addis Ababa, and colluded in the bombing of US embassies in East Africa. The truly major external aggression was Saddam's invasion of Iran, quietly supported by the Western powers and Saudi Arabia. It led to perhaps 1 million deaths, and to Saddam's subsequent attempted annexation of Kuwait to recoup his war debts. In short, both countries have had bad neighbourhoods, conducive neither to stability nor to foreign trade and investment, let alone to democratization or the peaceable management of domestic ethnic and religious tensions. These neighbourhoods partly explain periodic hyper-centralization in Baghdad and Khartoum and the military's dominance in politics. The two countries' immediate geopolitical neighbourhood has had independent causal force: no additional words about past Soviet or current US and Chinese policies towards either country, or Israel's history of support for the South Sudanese and the Kurds, are required to code these neighbourhoods as tough.

6. Within relatively recent memory both countries experienced autonomy and power-sharing settlements for their major disaffected peripheral regions, which failed.

In March 1970 Mustafa Barzani, for the Kurdistan Democratic Party, and Saddam Hussein, then vice-president of Iraq, negotiated an agreement which recognized a Kurdistan Region (with its final boundaries to be determined), to which was delegated extensive autonomy in language, education, policing and local government. It was also agreed that the KDP would nominate ministers to serve in the Baghdad cabinet. Iraq would be a bi-national state, and Kurdish an official language. The Baathists soon started to renege when it became plain that using fresh and fair census returns would deliver Kirkuk and other disputed territories to the Kurdistan Region. Barzani resumed armed struggle in 1974, rejecting the Baathist legislation of the agreement, confident that he would enjoy the support of the USA, Iran and Israel.Footnote 37 He was wrong: all three powers reversed their positions when the shah of Iran and Saddam cut a deal in Algiers in 1975. The betrayal and crushing of the Kurds led to Henry Kissinger's infamous defence that covert action ‘should not be confused with missionary work’.Footnote 38 After the defeat of Barzani, the Baathists kept a puppet legislature in Erbil, redrew the boundaries of the northern governorates and gerrymandered Kirkuk governorate, by reducing its size by half, subtracting and transferring Kurdish majority districts and adding Arab-majority districts from and to other governorates respectively (see Figure 2). These manipulations were reinforced by racist Arabization programmes, inducing southern Shiite Arab settlers into Kirkuk, expelling large numbers of Kurds and Turkomen, and attempting the coercive assimilation of the remainder. An autonomy experiment with some promise ended in cynical boundary manipulations, and ethnic expulsions.Footnote 39

Figure 2 The Saddamandering of Kirkuk after 1975

Much the same happened in South Sudan, almost step by step. In March 1972, at Addis Ababa, President Numairi's regime signed an agreement with the delegate of Major General Joseph Lagu of the Southern Sudan Liberation Front and Anya-Nya, creating a South Sudan Region, with its own legislature and executive, and with the right to use its preferred official language, English.Footnote 40 Southerners were to hold cabinet offices and senior positions in the Sudan army. As with the initial Kurdistan agreement, the Addis negotiators left the final boundaries of the region to subsequent determination: Article 3(iii) specified that areas that ‘were culturally and geographically a part of the Southern complex’ might have the chance to join South Sudan after a referendum. The South Sudan autonomy agreement lasted almost a full decade, and had a genuinely promising start, though nothing was done to resolve the boundary of the ‘southern complex’. Like Kurdistan, South Sudan had its internal divisions, often rooted in the tribal past. It had much deeper internal ethnic divisions, and lacked any extensive experience of self-administration, let alone self-government. When Numairi started to tack towards Islamists after 1977 he decided to take advantage of the array of internal Southern divisions, tribal-, regional- and personality-based. He first partitioned the South into three provinces, before unilaterally abrogating the Addis Ababa Agreement in September 1983, at the same time as he formally imposed sharia law throughout Sudan. Numairi and his successors sought to crush the new Southern armed forces that emerged in response, but never experienced a victory like that of Baghdad over Barzani. In another remarkable parallel, Numairi's Islamist successors encouraged ethnic expulsions in Abyei,Footnote 41 in southern Kordofan, and in Blue Nile states, that is in those parts of the ‘Southern complex’ expected to become part of the South as part of the 1972 Addis Ababa agreement.

Abyei, shown in Figure 3, is the homeland of Ngok Dinka, and the traditional grazing land of the Misseriya Arabs. It contains Sudan's largest oilfield in production, the most promising of other fields in production, and others unproven and promising. Whether it ends under the jurisdiction of Khartoum or Juba is therefore of material and not just ethnic importance. Abyei was transferred to Kordofan, outside the colonial South, in 1905, at the request of many Dinka tribal leaders, who believed that thereby they would be better secured against the incessant raids of slavers. Subsequently, however, the educated Dinka and now the overwhelmingly bulk of the Dinka population aspire to be part of South Sudan. Abyei is therefore Sudan's Kirkuk; and Kirkuk is Iraq's Abyei.

Figure 3 Abyei: Sudan's Kirkuk

SHORT-RUN PARALLELS

These long-run parallels should reinforce my present-centred question: why is Sudan breaking up, whereas Iraq may hold together? The evidence presented strongly suggests that the Kurds of the Kurdistan Region should want to secede from Iraq at least as vehemently as the South Sudanese have wanted to establish an independent sovereign state. Moreover, these six long-run parallels are matched by powerful recent parallels, which can be sketched more briefly.

In 2005 potentially transformative texts were signed and ratified in both countries, with the aid but not at the diktat of US diplomats. In 2005 the government of Sudan and the SPLM/SPLA signed a Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). The CPA was then embedded in an Interim Constitution. It ended the long war and gave the Khartoum government six years to make good its commitments to make unity attractive. A power-sharing government was established. Proportionality principles were applied both to an interim legislature and a freshly freely elected legislature, and in the composition of the cabinet, civil service, public bodies and the military. The government of South Sudan was granted far-reaching autonomy and veto rights, and its president was to be first vice-president of Sudan or the president – depending on election outcomes. Power-sharing was to be matched by wealth-sharing. An agreed formula would apply to the allocation of oil revenues. Disputed Abyei would have the right to join South Sudan in a referendum on the same day in January 2011 that South Sudan would vote either to endorse the newly attractive power-sharing formula or to secede. Separate security systems would be preserved, pending the referendum, but joint forces and separate forces would patrol the disputed territories.

Baghdad–Kurd relations underwent a similar textual transformation. In August 2005 the Iraqi National Assembly agreed a draft Constitution, subsequently ratified in a high-turnout referendum in October by four out of five of Iraq's voters, by 15 of its 18 provinces, and by over 95 per cent of Kurds in three provinces, as well as by the Kurdish-led majority in Kirkuk. A power-sharing transitional collective presidency was established for one term. Proportionality rules were to apply to the permanent legislature – with special protections for micro-minorities – and these have so far ensured multi-party coalition federal governments. The Kurdistan Region has far-reaching federal autonomy, and veto-rights over future constitutional change. The first president under the new order was a Kurd, Jalal Talabani. Power-sharing was matched by a wealth-sharing formula. Revenues from existing oilfields, to be jointly managed by regions, provinces and the federal government, were to be allocated across Iraq's regions and provinces, on a per capita basis, with some qualifications.Footnote 42 Newly exploited oilfields, by contrast, were to be owned by their regions and governorates, but federation-wide revenue-sharing formulae were not precluded and have been proposed by the Kurds. Disputed Kirkuk, and other adjacent territories, were to have their Baathist distortions rectified, and their status resolved through a referendum, which would let their peoples decide whether they wished to join the Kurdistan Region.

After the signing of the CPA, at least until the death of John Garang in a helicopter crash in July 2005, but also after, external expert opinion considered the break-up of Iraq more likely than the break-up of Sudan. Garang was expected to deploy his prestige and capabilities to mobilize a coalition of all the peripheries against the chastened Islamists with whom he would share power in Khartoum, and many expected him to have a good chance of winning any free contest for the presidency. After his death, many key SPLM figures in the North, notably General Secretary Pagun Amum, sought to keep Garang's agenda of transforming Sudan as a whole into a secular, multi-ethnic pluralist democratic federation. By contrast, before and after the making of the new Constitution, post-Saddam Iraq was descending into a ferocious intra-Arab civil war in which numerous Sunni Arab and Baathist organizations initiated sectarian war against the Shiite Arab-led government and civilians, only to receive far more than they had bargained for. In 2006 one of my colleagues in Kurdistan's constitutional advisory team, Peter Galbraith, published a book with the title The End of Iraq. His prediction was widely believed throughout Europe, North America and the countries of the Arab League. People expected the Kurds to leave a burning ship, not to help put out the fires (as they did when they lent troops to try to restore order in Baghdad in 2006–7). Recent history therefore strengthens our puzzle: if the Kurds and South Sudanese obtained similar agreements in 2005, and if Iraq's Arabs had an internal civil war after 2003 at least as violent as the civil war in Darfur after 2003, then why has Kurdistan remained within Iraq while South Sudan has left Sudan?

The answer does not simply lie in the respective texts of the constitutions, though that has to be part of the story. The CPA established that a referendum in January 2011 would give South Sudan the right to choose secession. If Kurds had demanded such a referendum, and successfully scheduled it within Iraq's Constitution, then they too might have been voting for secession in January 2011. Kurdish leaders, however, chose not to try to place the right of secession squarely within the text of Iraq's Constitution, though they did insist, at the initiative of President Barzani, that the Preamble would define Iraq as ‘a voluntary union of land and people’, thereby implicitly giving Kurdistan the right to determine whether the voluntary contract is broken in future. Instead, the Kurds traded. Rather than an explicit right of self-determination within Iraq's Constitution, they achieved their key negotiating objectives: extraordinary regional status; control over regional security; control over regional natural resources; regional legal supremacy in all but the very limited exclusive powers to be held by the federal government; and a process, including a referendum, that promised to bring Kirkuk and other disputed territories into the Kurdistan Region. Kurds sought the practicalities of maximum feasible statehood within Iraq rather than formal independence.

The question is why. Textualism does not tell all. At any recent juncture when they controlled the bulk of the region, i.e. any time after the First Gulf War, the Kurdish leadership could have held a referendum favouring secession, and would likely have won comprehensive endorsement from their voters. They can still do so in future. John Garang, by contrast with Barzani, was obliged to place the right to secession in the CPA in 2005 to keep his coalition together. Garang, by contrast with Barzani, strongly believed in and hoped to manoeuvre to make a success of ‘attractive unity’, i.e. to create a power-sharing Sudan under his leadership. His death was certainly contingent. Had Garang survived his helicopter crash, would the SPLM have advocated a vote for unity in January 2011? Would the SPLM's leaders have done more to ensure that unity was made attractive between 2005 and 2011?

The puzzling difference between South Sudanese and Kurdish behaviour is not resolved by pointing to the religious compositions of the two potentially secessionist regions, and their respective centres. Some think it natural that Christian and traditionalist South Sudan should secede from the Islamic North, whereas Muslim Kurds would be happier within predominantly Muslim Iraq. They are mistaken; Kurdistan is not staying within Iraq because most Kurds share Sunni Islam with Sunni Arabs. Most Kurds reject the puritanical, indeed fanatical and exclusionary, forms of Islam currently in favour among Sunni Arabs; they embrace tolerant and privatist Sufi traditions, and affiliate with a different Islamic jurisprudential school. More important, the political practice and dispositions of Sunni Arabs have made Kurds very tempted to secede from Iraq. Sunni Arabs have more often displayed racist contempt towards Kurds than Shiite Arabs. A Sunni Arab-led Baathist regime and a predominantly Sunni Arab-officered army genocidally assaulted Kurdistan. Most Sunni Arabs largely remain inveterate centralists, as well as unrepentant for complicity in the crimes of Baathism.Footnote 43 It was Saddam's primary victims, Kurds and Shiite Arabs, who primarily made the Constitution of 2005. They did not do so because they had convergent views on Islam.Footnote 44 It is true that the Khartoum Islamist regime's insistence on keeping the sharia in the North helped cement the argument for the secession of South Sudan, but the Kurds have not stayed within Iraq because most of them are Muslim.

Nor is the puzzle resolved through focusing on culture, ethnicity or language. Kurdistan is more homogeneous, culturally, ethnically and linguistically than South Sudan, and therefore might be expected to be more cohesive in its opposition to Baghdad than South Sudan has been towards Khartoum. One cannot even make much of the Kurdish civil war between 1994 and 1998, when the Kurds had internationally unrecognized autonomy, but spoiled their prospects through interparty fighting. The reason that emphasis is misplaced is because during the same decade the SPLM split, and there was a nasty Dinka- and Nuer-based civil war in South Sudan which Khartoum was able to exploit. The legacies of both internal civil wars underpinned fragilities in both South Sudanese and Kurdish movements, and therefore cannot account for the different dispositions of their leaders towards secession.

Is the resolution of the puzzle found in the fact that the Constitution of Iraq has worked better than the Comprehensive Peace Agreement? That may be part of the answer, but it is incomplete. Kurdistan has flourished since 2003, expanding its economy, and attracting extensive inward investment. It has had two free elections to the region's new assembly, won by coalitions led by the two historical rivals, the KDP and the PUK, who have alternated the premiership. The KDP has led the Regional Government in Erbil, with Masoud Barzani as president; the PUK, under Jalal Talabani, has led for Kurdistan in Baghdad. Moreover, three elections to Iraq's parliament have not, so far, produced a dominant Arab party or bloc determined to overthrow Kurdistan's autonomy. Kurds have held the foreign ministry as well as the presidency. They have played kingmakers, removing one prime minister, Jaffri, and twice put Maliki into the premiership, despite deep reservations on the second occasion – and current regrets. The Peshmerga are completing their unification as the Kurdistan Regional Guard and would put up stiff resistance to any incursions by the new Baghdad army. These facts suggest that Kurds are at last benefiting from membership of Iraq, on their own terms.

Granted, not everything is running smoothly. The new Baghdad governments have denied or sought to block Kurdistan's exercise of its rights over natural resources, especially its rights to issue its own contracts and control its own oil and gas exports. There has been no resolution of Kirkuk and the disputed territories, and the scheduled date has passed by which a referendum was to have been held. Within the KRG, the PUK has fractured, and a populist Goran Party in Sulaimania raucously opposes both the KDP and the PUK. Arab centralists have reemerged, willing to repeat the betrayals of the monarchy and the Baathists and overturn solemn constitutional commitments to the Kurds. Prime Minister Maliki has shown strongly authoritarian proclivities. Arab Iraq once again has a very large army, and a range of semi-incorporated militias. Yet Kurdistan's leaders have remained patient.

In Sudan the death of Garang froze the transformative dynamics that might otherwise have flowed from the CPA. After his death, both the NCP and the SPLM warily preferred to consolidate power in their respective zones before reluctantly holding much-delayed elections in April 2010, less than ten months before the scheduled referendum, partly because of disputes over the 2008 census results, which suggested that the South's electoral share of power in a united Sudan would be significantly less than under previous assumptions. Neither the elections in the South nor those in the North were fully competitive, free or fair. The SPLM's mandate of 93 per cent in the South undoubtedly reflected genuine strong majority support. The NCP's 68 per cent, though proportionally lower, looked highly inflated, partly because of boycotts by traditional Northern parties, and in Darfur, but economic growth and oil-based prosperity in the North meant that the incumbents would have done well in a more open and fair contest.

The aspiration of Garang to lead a multi-regional and multi-ethnic democratic opposition to power throughout Sudan may have been a fantasy. The 2008 census results, the official electoral performance of the SPLM in the North and the unwillingness of Arabs or the Arabized to vote for the SPLM in 2010 all suggest as much. The SPLM did not even push the international community to require Khartoum to oversee a fully free and fair election in the North in 2010, so we do not know what might have happened had the NCP faced the real prospect of regime change through a fully fair electoral contest. The SPLM preferred to keep its bargain with the devil it knew, i.e. to keep the referendum as a route to freedom, rather than risk a new Northern parliamentary coalition in the North betraying its promises to the South – as had happened in 1964 and 1986. Yet, like Iraq's Constitution, the CPA was not completely dishonoured. Some of the commitments made by the North in the CPA were followed up: the South did receive its promised share of oil revenues under credible monitoring, and the security pact held, despite multiple crises. The referendum, begrudgingly, was allowed to proceed. In sum, neither the Constitution of Iraq nor the CPA have been faithfully implemented to the letter and spirit by Baghdad or Khartoum, but they were partially implemented, and much more than many expected.

Another possible resolution to the puzzle is the existence of greater party and social pluralism within the Kurdistan Region by comparison with the utter dominance of the SPLM in South Sudan. Surely South Sudan was far more unified behind secession than the Kurdistan Region? That, however, is too quick a conclusion, even if we leave aside the fact that the elections and the constitutional referendum in the Kurdistan region were freer and fairer, and better internationally scrutinized. From 2005 Kurdish public sentiment was at least as intensely in favour of secession as that of the South Sudanese. In an unofficial civil society referendum held in Kurdistan on the same day as the October 2005 referendum to endorse the Iraqi Constitution, 11 out of 12 of those asked, in a very high turnout, endorsed independence for Kurdistan as their preferred option. The same respondents were simultaneously endorsing the Constitution of Iraq which had just been negotiated by their leaders.

These facts prove that a largely united leadership in the South followed or confirmed its public's secessionist sentiment, whereas a coalition of Kurdish leaders have successfully persuaded its public to back them in a federalist strategy – even though the Kurdish leaders and their public prefer independence in their hearts as much as the South Sudanese. In short, we must ask why the respective leaderships made the decisions they did during and after 2005. The answer lies in the strategic assessments and choices made by the Kurdish and South Sudanese leaders in their differing geopolitical neighbourhoods, and their different assessments of their respective Arab-majority centres. The answer is also to be found in the strategic choices of those with whom they negotiated.

South Sudan had a more facilitative external environment for secession. The SPLM had support, through time, albeit with variation, from Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda. Its precursors did too. Sudan's ambassador to Jordan, Mohamed Osman Saeed, indiscreetly said in November 2010 that, after secession, the North, ‘will gain a good neighbor and will be relieved from three lousy neighbors’.Footnote 45 He did not name the lousy neighbours, but, since the break-up, Sudan has no borders with Uganda, Kenya or the DRC. Predominantly Christian eastern black Africa has favoured an independent South Sudan as a buffer against Islamic and Islamist North Sudan, and in 1991 Eritrea and Ethiopia had set a regional precedent for a secessionist referendum. Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia believe that they can have good security, trading and energy pipeline relations with South Sudan. Together with a visibly more reluctant South Africa, these black African powers obliged the African Union to accept the agreement made in the CPA. Some African diplomats rationalized South Sudan's future independence as a belated act of self-determination for what had been a separately administered British colonial domain, but that was not the legal basis on which South Sudan's independence rested: it was founded on the North's consent.

The SPLM's leaders after August 2005 determined that their dead leader's vision of transforming the Arab-majority centre of Sudan was unachievable. They believed the predominantly Arab and Muslim North was obdurately unwilling to make a pluralist federation work. In 2009 in presentations and dialogues in Khartoum in which I participated before several of the dominant players in the NCP, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and the Umma Party, NCP leaders persistently ruled out what some called ‘the Nigerian option’,Footnote 46 i.e. secularizing the federation and confining the sharia law to Muslim-majority states. The other Northern party representatives remained silent. The NCP preferred, in short, to downsize Sudan, and to pursue its own political and religious agenda within a reduced state, rather than to make a fully pluralist accommodation with the South and non-Muslims. No better evidence for this view can be found than in President Bashir's declaration at a rally in the eastern city of Gederaf in December 2010, a few weeks before the referendum: ‘If South Sudan secedes, we will change the constitution and at that time there will be no time to speak of diversity of culture and ethnicity … Sharia and Islam will be the main source for the constitution, Islam the official religion and Arabic the official language.’Footnote 47 In Sudan, the South's potential federalists became committed secessionists because they (correctly) estimated that they faced a central power unwilling to make the necessary accommodations to make unity attractive, even though South Sudan faces a far tougher path to economic development than an independent Kurdistan Region, and even though the failure to resolve Abyei retains the potential to create a new war.

The KRG's geopolitical milieu, by contrast, is less hospitable for secession. Turkey, Iran and Syria have historically fiercely opposed Kurdish secessionism, though they have often exploited Kurdish rebel movements in contests with Baghdad governments. The USA has opposed Kurdish secessionism in Iraq, both in deference to its Turkish ally, and because since 1980 it has usually sought a strong Iraq to balance against Iran. Bluntly put, the USA was nominally neutral but actively favoured South Sudan's secession because it weakened what it regarded as a potentially disruptive Islamist government. By contrast, US ambassadors sweet-talked Kurds, but strongly opposed their secession from Iraq because Washington feared both strengthening Islamist Iran and aggravating Turkey.

For some, this comparative difference between the neighbourhoods of the Kurds and the South Sudanese, and the strikingly different US postures towards both regions, are all that is needed to resolve the puzzling difference between Kurdish and South Sudanese conduct after 2005. It is necessary, but not sufficient. Kurds are not wholly the prisoners of their neighbours, nor are they the dependent clients of the USA. They are active agents, and their assessment of their Arab-majority centre, and their own ‘grand strategy’, based on hard-won knowledge of their region, mattered.Footnote 48 Their grand strategy amounts to a defence-in-depth of dramatic federal autonomy within Iraq. It is intended to prevent Iraq from again becoming an over-centralized rentier state, which had led them to detention centres and mass executions, and to build the substance of independence and successful economic and political development without having the formal sovereign pleasures of South Sudan. Extensive autonomy and power-sharing are being defended internally through alliances within Iraq (based on vigilant and revisable judgements of shared interests with particular Shiite, Sunni and secular Arab parties and tribes). The task is made easier by the deep divisions between Shiite and Sunni Arabs, and through the Kurdistan Region's control over its own security. Proportional representation and multi-party coalitions, for now, have prevented any unified centralizing Arabist bloc from emerging – though the possibility cannot be excluded.

The Kurds' best hope of a principled Arab partner lay in their constitution-making alliance with the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI; now the Islamic Supreme Council in Iraq, ISCI). The ISCI is dominated by the leading Shiite family of the Hakims, who in 2005 were ardent champions of a southern region modelled on Kurdistan. But the ISCI has been badly damaged, both by its poor performance in running southern governorates, and by Iranian sabotage of what they had initially established as their front organization. ISCI has now quietly revised its postures and made alliances of convenience with the Sadrists. The weakening of the ISCI has obliged Kurds to be pragmatic in their deals with Arab parties.

Externally, Kurds have pursued constructive diplomatic and external relations with the USA, the EU and East Asia, and their oil and gas companies – all made feasible under their new constitutional rights. They have especially pursued an active Westenpolitik Footnote 49 with Turkey, and, more quietly, détente with Iran, to create commercial and political alliances, and to entrench recognition of the KRG's constitutional rights. To attract inward investment the KRG has provided the laws of a mature capitalist legal order. To protect the KRG's revenue interests, its people and their environment, its policymakers took care in the drafting of the Region's Oil and Gas Law. The KRG prioritized its own law only after the failure of the federal Iraqi cabinet and parliament to make progress with a draft law of February 2007. The KRG's strategy has been to build a credible base of inward investment, from which it could then negotiate more productively with its federal partners in Baghdad, both on Iraq-wide revenue-sharing, and on production, marketing and exporting. It has had obvious successes, though the jury remains out. The KRG is prioritizing resolving disputes over oil and gas because these are central to its budget, its economic development and funding the Peshmerga, while it is prepared for a much slower pace of change on resolving the disputed territories.

Relations with Turkey have shown zigzags, but the overall trajectory has been positive. It is Turkey itself which has truly zigzagged. Initially shocked by the US decision to enforce regime change in Iraq, Turkey feared that the removal of the Baath would lead to an independent Kurdistan and would revive the PKK. Some of its ‘deep State’ special operatives, intent on the assassination of Iraqi Kurdish politicians, were arrested by American soldiers. But Turkey's Justice and Development (AKP) government (and some of its military) have rethought their positions, in private and in public. They realized that the Turkoman minority is insufficiently weighty to provide leverage in the new Iraq, especially within Kirkuk. More significantly, they realized the advantages of building constructive interdependence with what they now are prepared to call the Kurdistan Region (rather than Northern Iraq). The KRG recognizes that its relations with Ankara are easier if they fit Turkey's energy ambitions, and its ethnic politics. Turkey's ambitions include being the transit hub for Caucasian, Caspian Sea and Iraqi oil and gas to Europe, a development the EU welcomes to lessen its dependence on Russia. Ceyhan on the Mediterranean has long been an export route for the Kirkuk oilfields, but has had reduced volumes since the Gulf War of 1991. Turkey's policymakers realize that the Shiite leaders in the Baghdad federal government, formally or informally, have prioritized the redevelopment of Iraq's southern oilfields. This, in turn, has made Turkey's policymakers better disposed towards the KRG, not only a champion of its own new fields, and of export through Turkey, but also of repair and renewal of the Kirkuk oilfields. The KRG has also promised to be an effective agency for Turkey in achieving the peaceful dissolution of the PKK within Turkey, though that requires Turkey to complete its improved treatment of its own Kurds. In short, newly constitutionalized Kurdish nationalism within Iraq is – at least potentially – allying with newly democratized soft Islam in Turkey. Both are affected by the fact that Kurdish votes matter, and are potentially pivotal, in Iraq and in Turkey.

The federalization of Iraq, by comparison with the break-up of Sudan, is therefore not merely a realist tale of comparative state neighbourhoods, or of the impact of US power and preferences. It is also a tale of the greater democratization of Iraq – and Turkey – and regime transformation compared with Sudan. The enhanced potential electoral pivotality of Kurds in Iraq and Turkey has been decisive in shaping KRG grand strategy, a pivotality that the South Sudanese were much less likely to command in a united Sudan once the 2008 census results were reported. Kurdish strategic adaptation, to remake both Iraq and Turkey in their interests, is the key and little understood part of the federalization of Iraq. The Southern Sudanese strategic reappraisal of Garang's vision after the census returns, and its freshly critical evaluation of the dispositions of Northern parties, are the key and insufficiently understood parts of the break-up of Sudan.

These arguments help explain why Kurdish leaders, for now, are committed to the federalization of Iraq, whereas the South Sudanese committed to independence. Their negotiating partners also mattered. Key North Sudanese were downsizers. They preferred a smaller and more homogeneous Sudan to the compromises required by a pluralist federation. They may also have miscalculated their bargaining power with a newly independent South Sudan, believing that they could easily extract enough rent from their pipelines to make good most of their losses of revenue. The Arabs of Iraq, by contrast, have not been downsizers, so far, but that is not too difficult to explain. Sunni Arabs want to keep the Kurds in Iraq because a Kurdless Iraq would have a very large Shiite majority. The Shiite Arabs want to keep the Kurds in Iraq to balance against the Sunni Arabs. Each bloc of Arabs is reluctant fully to make the concessions that Kurdistan wants, but someone usually breaks from their ranks to make short-run deals with the Kurds. Democratic rules may make this a sustainable game.

No comment has been made on whether the South Sudanese or the Kurds are making the right choices, given their interests, and their appraisals of their geopolitical environments. Nor has it been suggested that the federalization of Iraq is secure, or that the secession of South Sudan will proceed smoothly. An explanation has, however, been presented that accounts for why Kurdish and South Sudanese leaders rationally chose different strategies during and after 2005, even though both of them led mass publics that longed for independence from states that had never earned their allegiance, and had never done enough to deserve it.

Twinned comparisons are not large-N studies. Of what general significance is this comparison for political science? First, it suggests that pre-colonial and colonial pasts matter: the colonial and post-colonial eras did not erase the prospects of all restoration projects; old polities or regions can resurrect. Second, even when faced with a clear but weakened domestic adversary, secessionists and autonomists have to overcome huge collective action problems and usually a regional and global order hostile to their preferences. Third, autonomy, federal or otherwise, need not lead to secession: nationalists are strategists, and may settle for less than their optimum. Fourth, nationalists' projects are facilitated when they are faced with ‘downsizing’ centres. Explanations of secessions should focus therefore on what accounts for the development of downsizing mentalities. Lastly, democratization may enhance the credibility of federalism as a settlement for the historically excluded, and their parties, but it will only convincingly do so when the group in question obtains pivotality.