Background

Prevalence of psychological distress is high among populations in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) that are affected by conflict, poverty, and violence (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Chatterji, Evans-Lacko, Gruber, Sampson, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Borges, Bruffaerts, Bunting, de Almeida, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, He, Hinkov, Karam, Kawakami, Lee, Navarro-Mateu, Piazza, Posada-Villa, de Galvis and Kessler2017; Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019). LMICs are often unable to cope with high rates of distress, due to fragmented health systems and limited number of mental health professionals (Jordans and Tol, Reference Jordans and Tol2013). In such contexts, interventions are needed that can be scaled-up to reach larger populations, can be delivered through routine health care, and utilize concepts of task-sharing, i.e. use of non-specialists to deliver intervention components (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana, Bolton, Chisholm, Collins, Cooper, Eaton, Herrman, Herzallah, Huang, Jordans, Kleinman, Medina-Mora, Morgan, Niaz, Omigbodun, Prince, Rahman, Saraceno, Sarkar, De Silva, Singh, Stein, Sunkel and Unützer2018). Along with expanding the reach of interventions, it is necessary to assure that programs are culturally compelling (Panter-Brick et al., Reference Panter-Brick, Clarke, Lomas, Pinder and Lindsay2006). Global mental health efforts have also previously been criticized for cultural insensitivity and lack of alignment with local norms, family structures, daily practices, and cultural conceptualizations of distress (Summerfield, Reference Summerfield2013). Changing the treatment without modifying implementation strategies may lead to limited delivery or uptake of the new services (Jordans and Kohrt, Reference Jordans and Kohrt2020). Therefore, cultural adaptation of both content and implementation strategies are needed for effective scale-up (Chambers and Norton, Reference Chambers and Norton2016).

Overview of cultural adaptation methods

The main intention for cultural adaptation frameworks is to increase the cultural acceptability and effectiveness of the psychological treatment. This is accomplished by making changes that align with the culture of the beneficiary population, while maintaining the components of the evidence-based research that supports the treatment (Bernal and Scharró-del-Río, Reference Bernal and Scharró-del-Río2001; Sue, Reference Sue2003; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Nguyen, Mannava, Tran, Dam, Tran, Tran, Durrant, Rahman and Luchters2014). There have been many attempts to organize the theories suggested by the existing frameworks. We have condensed these theories into three main distinctions that need to be balanced when adapting treatments (Griner and Smith, Reference Griner and Smith2006; Bernal and Domenech Rodriguez, Reference Bernal and Domenech Rodriguez2012, p. 20; Huey et al., Reference Huey, Tilley, Jones and Smith2014; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Ibaraki, Huang, Marti and Stice2016; Nisar et al., Reference Nisar, Yin, Yiping, Lanting, Zhang, Wang, Rahman and Li2020).

The first distinction is surface v. deep adaptations. Surface structure adaptations refer to modifying superficial characteristics, such as translating treatment materials, to better fit preferences of the beneficiary population (Burge et al., Reference Burge, Amodei, Elkin, Catala, Andrew, Lane and Seale1997; Ahluwalia et al., Reference Ahluwalia, Baranowski, Braithwaite and Resnicow1999). Deep structure adaptations target cultural values, norms, traditions, beliefs, and the beneficiary population's perceptions of the illness's treatment and etiology. Surface level adaptations, such as pictorial material depicting participants ethnically similar to beneficiary populations, resulted in discernable improvements in participant retention (Harachi et al., Reference Harachi, Catalano and Hawkins1997; Kumpfer et al., Reference Kumpfer, Alvarado, Smith and Bellamy2002) highlighting the importance of even ‘simple’ cultural adaptations (Chowdhary et al., Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans, Rahman, Verdeli, Araya and Patel2014).

The second distinction is between the adaptations of core v. peripheral aspects of the intervention. Core components are the main evidence-based ingredients of an intervention that are integral to the treatment (Chu and Leino, Reference Chu and Leino2017; Nisar et al., Reference Nisar, Yin, Yiping, Lanting, Zhang, Wang, Rahman and Li2020). Peripheral components are related to the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention and exist to support the core components and the goals of the treatment. Although promoting adaptations that are responsive to the needs of the beneficiary population, it is also important to follow the intervention as intended. This fidelity v. fit distinction must be balanced to promote cultural appeal to the intervention while also following tried and tested methods to increase effectiveness (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Barrera and Martinez2004; Kilbourne et al., Reference Kilbourne, Neumann, Pincus, Bauer and Stall2007). Despite the clarity brought about by identifying three key distinctions in the literature, these aspects of cultural adaptations are not straightforward. For example, common factors in psychotherapy such as therapeutic alliance, changing expectations of personal effectiveness, and encouragement (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Reijnders and Huibers2019; Heim and Kohrt, Reference Heim and Kohrt2019) could be classified as peripheral, or supportive components, but in fact may be core and integral to the success of the treatment.

Despite a range of theoretical lenses to view cultural adaptation, the adaptation procedures have been criticized as difficult to replicate in real-world settings and lacking in transparency (Chu and Leino, Reference Chu and Leino2017; Escoffery et al., Reference Escoffery, Lebow-Skelley, Haardoerfer, Boing, Udelson, Wood, Hartman, Fernandez and Mullen2018). Additionally, most adaptation studies of psychological treatments have been conducted with ethnic minorities in high-income countries (HICs) (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009). Although this is an overlooked and often marginalized population, these minorities are based in settings where resources such as time and personnel may not be as constrained as in low-resource and humanitarian settings that require rapid implementation. These constraints create unique needs, especially in LMICs and humanitarian settings, where a transparent, thorough, and prescriptive framework is necessary to guide rapid and systematic adaptions.

Aim

Our aim was to develop a cultural adaptation model that addresses gaps in current approaches. We piloted our adaptation approach in the context of Group Problem Management (PM+) in Nepal (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020). Group PM+ is a five-session intervention delivered by lay health workers, for adults with symptoms of common mental health problems (e.g. depression, anxiety, stress, or grief) (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015). The therapeutic aim of the intervention is to improve one's management of practical problems (e.g. work burden and relationship conflict), by utilizing four core strategies, or mechanisms of action (see Table 1). Participants are encouraged to practice and review these mechanisms of action in between sessions. Each session is 90 min and each PM+ group has 6–8 participants.

Table 1. Mechanisms of action of intervention

Note: The first four sessions of PM+ each address a specific mechanism of action. The fifth and last session is a review of the mechanisms of actions learned in the intervention.

When conducting the cultural adaptation process for Group PM+, we documented the process and identified key adaptations. After implementation, we gathered data on how the adapted and contextualized intervention was perceived by participants, community members, and families. This paper aims to meet the following objectives:

(1) Create explicit guidance for cultural adaptation and contextualization that can be applied to various populations with a focus on mechanisms of action, implementation, scalability, and quality monitoring.

(2) Report on the cultural adaptation process of Group PM + in Nepal.

(3) Gather feedback from program stakeholders to evaluate the implementation of the adaptations.

(4) Suggest the most valuable steps in adapting an intervention under time and resource constraints.

The resulting methodology is the mental health Cultural Adaptation and Contextualization for Implementation (mhCACI) procedure. This paper will first outline the step-by-step mhCACI adaptation procedure followed by an overview of the key adaptations made to the Group PM+ intervention. We will then highlight how this procedure can be used to adapt future interventions and treatments in various contexts.

Although an existing cultural adaptation methodology has been presented to adapt individual PM+ with refugee populations (Perera et al., Reference Perera, Salamanca-Sanabria, Caballero-Bernal, Feldman, Hansen, Bird, Hansen, Dinesen, Wiedemann and Vallières2020), our approach has several advantages including a central focus on the processes that lead to change (i.e. mechanisms of action), attention to implementation parameters beyond content modification (e.g. how do participants become engaged in the intervention and how is it explained to the public and families), rigorous documentation, and creation of a cultural distress model that goes beyond simply translating mental health terminology.

Methods

Setting

Nepal is a low-income country with a history of internal conflict, political instability, and natural disasters. In 2015, an earthquake resulted in injuries, deaths, and displacement. A total of 34.3% and 33.8% of participants in an earthquake-affected district scored above the validated cut-off scores for depression and anxiety, respectively (Kane et al., Reference Kane, Luitel, Jordans, Kohrt, Weissbecker and Tol2018). To date, there have been minimal efforts to adapt psychological treatments in Nepal (Ramaiya et al., Reference Ramaiya, Fiorillo, Regmi, Robins and Kohrt2017). Group PM+ was considered an appropriate intervention to test in this setting due to its scalability and task-sharing approach. The Group PM+ intervention's adaptation process and feasibility trial was conducted in Sindhuli district, which was heavily impacted by the 2015 earthquake (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, van't Hof, Luitel, Turner, Marahatta, Nakao, van Ommeren, Jordans and Kohrt2018, Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020). The adaptation process and implementation of the trial was conducted by the staff of Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO) Nepal based in Kathmandu, Nepal (Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Luitel, Koirala, Adhikari, Gurung, Shrestha, Tol, Kohrt and Jordans2014).

Ecological validity model (EVM) and replicating effective programs (REP) frameworks

We built the mhCACI procedure upon the Ecological Validity Model (EVM) to guide our adaptation of the Group PM+ intervention content (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995; Bernal and Sáez-Santiago, Reference Bernal and Sáez-Santiago2006). The EVM was selected because it is based on the view that individuals must be understood within their cultural, social, and political environment. The EVM framework serves to ‘culturally center’ an intervention through eight dimensions that must be incorporated for an intervention to have ecological validity and be embedded within the cultural context (Bernal, Reference Bernal2003). These dimensions include language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context (Table 1 in online Supplementary material).

We also structured the adaptation and contextualization methodology within the Replicating Effective Programs (REP) framework, which considers intervention training, supervision, and fidelity assessments as crucial components to the implementation of effective interventions while allowing for local flexibility (Kilbourne et al., Reference Kilbourne, Neumann, Pincus, Bauer and Stall2007). REP includes four phases: (1) pre-conditions (e.g. identifying need and target population), (2) pre-implementation (e.g. community input and training), (3) implementation (e.g. program delivery and evaluation), and (4) maintenance and evolution (e.g. re-customization and preparing intervention for implementation in another context or dissemination) (Cabassa and Baumann, Reference Cabassa and Baumann2013).

Study methodology

This study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03359486). As part of the 10-step cultural adaptation model, qualitative interviews were conducted with program stakeholders to gather feedback on the acceptability, scalability, and implementation of the adaptations (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020). Integrated within the maintenance and evolution phase, a subsequent Group PM+ evaluation will be conducted in Nepal with the integrated changes in implementation methods (van't Hof et al., Reference van't Hof, Sangraula, Luitel, Turner, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Shrestha, Bryant, Kohrt and Jordans2020).

Overview of mental health cultural adaptation and contextualization for implementation (mhCACI) methodology

The adaptation process was an ongoing, iterative process with some overlapping steps. Questions addressed in each step were based on what was or was not answered in the prior steps and the iterative process of this methodology more easily allowed for finding a balance between fidelity v. fit. The format of this methodology was participatory and involved a high level of engagement with the communities where the intervention was delivered.

A detailed data collection process and documentation system allowed us to ensure that each adaptation made was based on evidence. We created a matrix before the start of the adaptation process based on the FRAME approach for documentation (Wiltsey Stirman et al., Reference Wiltsey Stirman, Baumann and Miller2019): (1) the eight broad dimensions from EVM, (2) implementation strategy (what exactly should be changed in the intervention material), (3) rationale for change (description of why it should be changed and what it would accomplish for the intervention), and (4) evidence for change (which adaptation steps the change was a result of). All changes and adaptations were listed in the EVM matrix during the length of the process (Table 3 in online Supplementary material).

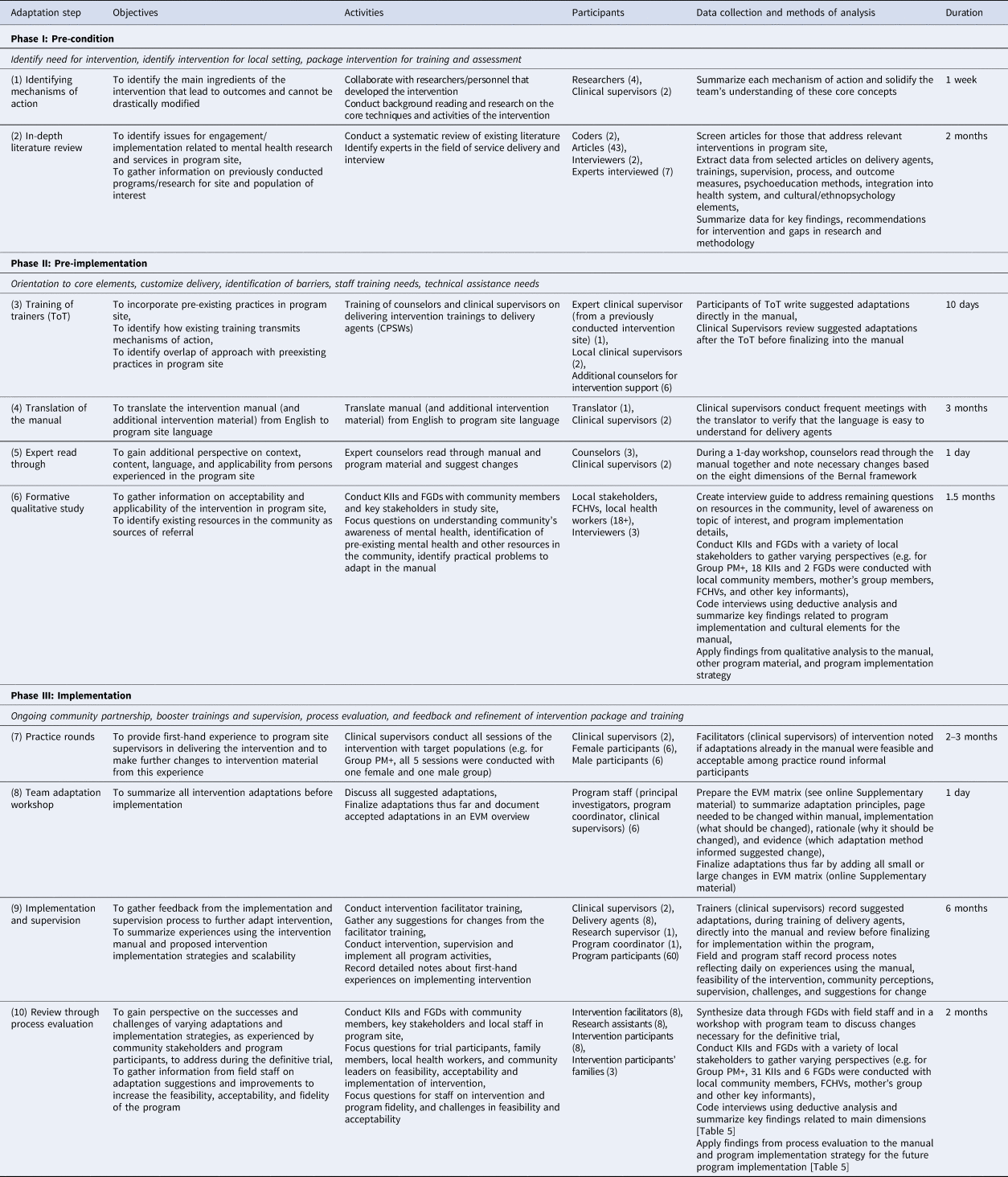

The following approach charts the cultural adaptation process from preparation through implementation (see Table 2). We present the steps as they would fit into the first three phases of the REP framework (pre-conditions, pre-implementation, and implementation).

Table 2. Overview of adaptation steps: activities, participants, and methods of analysis outlined according to phases of the Replicating Effective Programs framework

Phase I: pre-conditions

1. Identify the key mechanisms of action

The mechanisms of action are the process by which a psychological intervention reduces distress and supports behavioral change (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2007). Mechanisms of action, or the techniques participants learn in each PM+ session, were identified as the core of the intervention in previous trials (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Schafer, Dawson, Anjuri, Mulili, Ndogoni, Koyiet, Sijbrandij, Ulate, Harper Shehadeh, Hadzi-Pavlovic and van Ommeren2017; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Khan, Hamdani, Chiumento, Akhtar, Nazir, Nisar, Masood, Din, Khan, Bryant, Dawson, Sijbrandij, Wang and van Ommeren2019). Therefore, these techniques were also identified as the key mechanisms of action in this trial (see Table 1).

2. In-depth literature review (and consulting with experts)

A systematic review of existing literature on mental health interventions in Nepal was conducted. Databases such as PubMed, PsychInfo, and PsychiatryOnline were searched as well as gray literature from policy briefs and annual reports of local organizations. The review extracted information on cultural concepts of distress, Nepali ethnopsychological frameworks, and prior adaptations of mental health interventions in Nepal. Ethnopsychological frameworks are local models of understanding suffering, mind-body relationships, and concepts of the self (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Maharjan, Timsina and Griffith2012). Although not a formal part of the literature review, interviews were also conducted with staff from leading mental health organizations in Nepal to identify issues for community engagement and implementation related to mental health research and service delivery in Nepal. Data were summarized for key findings, gaps in research and methodology, and recommendations for Group PM+ adaptation in Nepal.

Phase II: pre-implementation

3. Training of trainers (ToT)

Clinical supervisors and supporting counselors were given a 10-day training by a Group PM+ trainer from a previous study site. The participants of this ToT identified overlap of approach with preexisting practices in the program site and suggested culturally fit adaptations to intervention content. The Group PM+ clinical supervisors gathered the adaptations suggested by the trainees and reviewed them before finalization. Suggestions that modified the mechanisms of action were rejected. Other suggestions that adapted other aspects of the intervention, such as the language or metaphors, were documented, accepted and finalized into the manual by the clinical supervisors.

4. Translation of manual

Clinical supervisors incorporated initial changes into the English manual which was then translated to Nepali by a professional translator. Clinical supervisors regularly reviewed the translator's progress to ensure that the manual could be understood by non-specialist delivery agents. This was an ongoing process and focused on language rather than the content of the manual. Study staff without a clinical background also reviewed the manual to ensure its comprehensibility for lay persons.

5. Expert read-through

Experienced bilingual Nepali psychosocial counselors read through the Nepali language intervention manual and suggested changes in language and content to fit into the cultural context during a 1-day workshop. The main objective of this step was to gain additional perspective from persons experienced in the program's mental health context on the intervention's content, language, and applicability.

6. Formative qualitative study

Based on gaps identified in prior steps, a formative qualitative study was conducted regarding community's awareness of mental health, collaboration with pre-existing community resources and identification of practical problems faced by community members. Key informant interviews (KIIs) (n = 18) and focus group discussions (FGDs) (n = 2) were conducted with female community health volunteers (FCHVs), leaders, health workers, and community members. Interviews were coded by two coders (MS and RG) using deductive analysis. Key findings related to program implementation and cultural elements were added to the manual and the program implementation strategy. This included the addition of community sensitization events and meetings with the families of participants, refining recruitment of participants, and clarifying referral pathways.

Phase III: implementation

7. Practice rounds

Clinical supervisors conducted Group PM+ practice rounds to gain experience delivering the five-session intervention, gather feedback from the participants on their comprehension and relatability of the intervention, and apply any further changes to the manual and implementation strategy. Practice rounds were conducted with one male group and one female group from a nearby community. After each session, the participants were encouraged to give feedback to the facilitators on content, language, materials and methods used, and facilitation skills. This information was collected through informal interviews with the participants and noted down by the clinical supervisors.

8. Team adaptation workshop

A team workshop with all core program and research staff was conducted to summarize all intervention adaptations listed to date on the EVM matrix. Program staff also modified competency and quality monitoring procedures. Once all adaptations were thoroughly discussed, clinical supervisors made final changes to the manual before the start of the trial.

9. Program implementation, supervision, and process evaluation

Lay Nepali community members were recruited to deliver Group PM+ to their communities (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, van't Hof, Luitel, Turner, Marahatta, Nakao, van Ommeren, Jordans and Kohrt2018, p. 201, Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020). During the Group PM+ training, the facilitators were encouraged to suggest changes in the manual's language and feasibility and acceptability of the proposed implementation strategy. We employed a randomized control trial design where the two chosen Village Development Committee in Sindhuli district 120 participants were randomly assigned to enhanced usual care or PM+. As part of supervision, all staff recorded notes about first-hand experiences working on program recruitment, delivery, and engagement with the community, and shared these experiences with their supervisors. Some changes were made in real-time while others required further discussion at the end of the trial.

After completing the intervention, 31 KIIs and six FGDs were conducted with field staff, intervention participants, participants' families, and other key community stakeholders to gain perspective on the successes and challenges of varying adaptation and implementation strategies. A deductive data analysis process was used; key themes were identified prior to analysis and a codebook was developed (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020). Interviews were coded using NVivo software and the two coders (MS and RG) established an acceptable inter-reliability rate (=0.8) during the coding process. Key implementation challenges, successes, and further suggestions for the program were extracted and summarized from the interviews.

10. Re-customization of intervention

Field notes from program implementation and supervision, along with results of the process evaluation were gathered and synthesized into the EVM matrix (Table 2 in online Supplementary material) to highlight suggested key changes for re-customization of the intervention. The program staff then discussed appropriate changes related to program content, recruitment methods, quality assurance, and strengthening the mechanisms of action. Program materials were further revised to reflect the outcomes of implementation assessment before implementation in a new context.

Results

Conceptualization of stress and tension

As a central focus of the adaptation process, we aimed to create a conceptual model by linking the mechanism of action to how distress was experienced in this context. Tension was used as a non-stigmatizing idiom of distress, as a proxy to depression complaints which is targeted by the intervention, and was commonly used in lay-Nepali language by community members of all ages, gender, and socioeconomic status (Rai et al., Reference Rai, Adhikari, Acharya, Kaiser and Kohrt2017). The tension ethnopsychology model was conceptualized during the workshop as the team was finalizing the adaptations before the trial (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Tension conceptual model.

According to the ethnopsychology model, adversity or practical problems lead to tension, which can have a physical manifestation and lead to emotional problems. Tension can also lead to a lack of energy, feeling unmotivated, and isolation from friends and family. Each Group PM+ session addresses managing the roots of tension or its effects, which are also integrally linked with one another. Because of the contextual fit of the model, elements of the tension model were also used during facilitator training and the recruitment process to explain the effects of adversity on our lives to local community members.

Key adaptations

Adaptations were systematically documented in the EVM matrix (see online Supplementary material). Key adaptations are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Key adaptations from each step outlined according to phases of the Replicating Effective Programs framework

Superscript numbers refer to domains of Bernal's Ecological Validity Model: 1Language, 2persons, 3metaphors, 4content, 5concepts, 6goals, 7methods, 8context.

Pre-conditions

Identification of distress and relatability of clinical content

Understanding sources of distress was key to identifying need for intervention in the local community. Identified daily stressors, such as financial burden, grief, and migration, were incorporated into the stories used during sessions. Participants in the trial found these problems, the case story, and pictorial representations on posters to be highly relatable (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020). Clinical supervisors and facilitators noted that physical health was a source of stress for the majority of program participants. The feedback received demonstrated that more content was necessary to address physical problems and train facilitators on how to work with participants who did not discuss their emotional problems. Some suggestions included adding characters in the case story that faced more physical ailments, and posters representing these problems to validate participants' distress. Facilitators should also be trained further in how somatic problems are connected to mental well-being, using the tension model as a guide.

Pre-implementation

Use of local idioms to increase acceptability and reduce stigma

Community sensitization events were a vital component of recruitment to address the stigma and lack of awareness of mental health issues at the program site (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020). Facilitators invited community members to discuss causes of tension and man ko samasya, which is Nepali term for heart-mind problems refering to general psychological distress (Kohrt and Harper, Reference Kohrt and Harper2008), and impact of adversity on personal behaviors and emotions. The participatory format of engaging with the community during sensitization activities while using de-stigmatizing terms was successful in encouraging community members to volunteer for study screening. In further efforts to reduce stigmatization by the community for participating in the intervention and self-stigmatization by the participants themselves, key adaptations were made to the metaphors, the concepts, and the intervention packaging. A context appropriate name was voted on by the local staff that chose Khulla Man, (a Nepali idiom for opened heart-mind, meaning open-hearted). Some participants described their own heart-mind as being Khulla (open) or having a Khulla Man after the sessions. Similarly, the tension model conceptualized before program implementation was successful in supporting the facilitators' understanding of how each session aimed to reduce stress.

Implementation

Recruitment, training, and supervision of intervention facilitators

Recruiting, training, and hiring local lay workers was a critical adaptation to increase scalability of the Group PM+ intervention. A 20-day Community Psychosocial Worker (CPSW) Training, as is standard to certify this cadre of workers in Nepal, was delivered before 10 days of Group PM+ training. As indicated by the qualitative interviews, participants found comfort in having their groups led by a facilitator who was from a familiar location but who the participants did not know very well. Similarly, helpers were hired to assist the facilitators during the sessions. Because concepts of time and punctuality were flexible in this context, it was noted that having a helper remind participants to arrive on time helped increase attendance and reduce drop-out rates.

Implementation

Engagement with potential beneficiaries

The Community Informant Detection Tool (CIDT) helped easily identify members of the community experiencing mental health symptoms through using vignettes and pictures (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Kohrt, Luitel, Komproe and Lund2015). A general distress, man ko samasya, version was developed for this trial. FCHVs, mothers' group members, and other local community leaders received a 1-day training on how to use this tool to refer those with general distress to the study. They were also trained on the severe mental health CIDT version to identify who not to recruit. However, this led to confusion among some trainees who referred those with severe mental illness to the study, since severe symptoms are more noticeable than those with general distress. For future scalability and dissemination, it is recommended to train local community members on using the general distress version only and with regular on-site supervision.

Reinforcement of mechanisms of action

A combined competency and fidelity checklist was created based on both Group PM+ elements and common factors in psychological treatments, drawn from the enhancing assessment of common therapeutic factors tool (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Rai, Shrestha, Luitel, Ramaiya, Singla and Patel2015). Clinical supervisors attended at least two of the five sessions per PM+ group and used the fidelity checklist to measure facilitators' competency in delivering the intervention. Facilitators also used the checklist while conducting sessions to ensure that the mechanisms of action were addressed thoroughly. The Reducing Tension Checklist (RTC) tool was also developed to assess whether participants applied the mechanisms of action learned in the sessions to their daily lives. This tool was used pre- and post-intervention (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020).

The participants noted that of the different techniques they learned, the deep breathing technique was the most memorable and used the most outside of the sessions (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020). This technique was noted as the most tangible, accessible, and lead to the most immediate results. However, facilitators found it difficult to track how often participants were practicing at home.

As a result of the process evaluations, the team decided to incorporate more imagery and memorable metaphors to each of the sessions. For example, the second session focused on effective problem solving, was considered by the facilitators to be one of the most difficult sessions to deliver and for real-life application outside the sessions. Therefore, the definitive trial incorporated an image of a hand with a step for problem solving written on each finger. A card was created for each of the five sessions with visual imagery of each mechanism of action on one side and a space to plan when to practice on the other side. This set of cards was called the tension toolkit (Fig. 1 in online Supplementary material). We also incorporated several concrete tools to support each of the sessions, such as a small pouch (thaili) after the third session for participants to store a rock, or kernel of corn each time they do a pleasurable activity at home. The objective of these tools is to provide physical items to help participants practice skills.

Discussion

Outputs and applications

This study provides a methodology for the mhCACI that incorporates cultural adaptations to clinical content, scalability, and implementation. Because this cultural adaptation methodology has been integrated into the REP framework, this study further bridges the gap between cultural adaptation and implementation science research (Cabassa and Baumann, Reference Cabassa and Baumann2013; Mutamba et al., Reference Mutamba, Kohrt, Okello, Nakigudde, Opar, Musisi, Bazeyo and de Jong2018). The scalability and implementation aspects were shown to be just as important as the clinical content when adapting an intervention. A tension ethnopsychology model was developed as a conceptual foundation to key adaptations. Adaptations were made to case stories, visuals, and materials to reflect the context. Using a context appropriate intervention name, utilizing the CIDT for recruitment, and conducting community sensitization events supported in reducing the stigma. We also adapted the facilitator trainings, and created the fidelity checklist, RTC, and tension toolkit to reinforce the mechanisms of action and ensure quality of care. As part of this study, we have also designed a clear and detailed documentation process that will assist in conducting evidence-based adaptations to future interventions.

The specific adaptations made to the intervention as well as the contextualization of the implementation process were demonstrated to be feasible and acceptable. The intervention had a high retention rate with 75% of the participants completed 4–5 sessions (Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, Turner, Luitel, van ‘t Hof, Shrestha, Ghimire, Bryant, Marahatta, van Ommeren, Kohrt and Jordans2020). All facilitators (n = 4) scored above a 75% on the fidelity checklist developed to measure the competency and overall fidelity to the intervention. The intervention group showed an improvement in outcomes, especially in general psychological distress. Qualitative interviews with the Group PM+ facilitators, supervisors, and beneficiaries suggest that benefits can be attributed to the cultural adaptations and contextualization process.

In reality, adaptation processes are often conducted constrained by staff and time in low-resource settings. Therefore, we have created one mhCACI procedure with two versions: the first model to be used in contexts with at least modest time and resources, and the second in contexts with high-level constraints (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Cultural adaptation step-by-step guide.

For the shorter mhCACI procedure, the literature review step has been modified from in-depth to an overall review. The expert read-through has been eliminated since we found that clinical staff who developed in-depth knowledge of the intervention when conducting prior adaptation steps were best fit to suggest the most meaningful changes. Though we conducted a formative qualitative study as part of the adaptation process, we found that an assessment of the intervention site could have sufficed for the purpose of adaptation. This assessment should be tailored to the needs of the intervention and should be approached as a method to gather information from and to engage the local community, which was proven to play a large role in the success of the intervention. The practice round steps resulted in the greatest number of adaptations and were important steps in addressing the logistical aspects of the intervention, such as time management, venue location, and to gather feedback from participants within the targeted population. Therefore, we recommend shortening other steps and focusing mainly on conducting several practice rounds or sessions as part of the adaptation process, if under extreme time constraints.

The eight dimensions of cultural adaptation, as presented by Bernal and colleagues (Bernal and Domenech Rodriguez, Reference Bernal and Domenech Rodriguez2012), were helpful in conceptualizing the types of changes that could be made, while preserving the treatment's core mechanisms of actions. However, we found that a few of the dimensions, such as content and context, are similar in their definitions and overlapped with one another. As a result, we found it best to focus less on which category an adaptation would be labeled as, and instead refer to the eight dimensions occasionally to assure that they are all being addressed as a part of the adaptation. In this way, the eight dimensions can serve as a starting point rather than a guide.

Limitations

Limitations to the study must be accounted for before using this adaptation model for other interventions. It is difficult to identify which adaptations were the most important and which had the highest impact on the intervention because there are many potential factors contributing to its success. The results are also limited to qualitative work and the participants', staff, and stakeholders' perceptions of effectiveness. Regardless of compressing the adaptation process to fit resource limited contexts, the nature of the cultural adaptation itself is iterative and requires depth and heavy documentation. If a single professional wishes to adapt a program and is especially limited on human resources, collaboration with external experts is recommended to complete the adaptation steps.

Conclusion

This study proposes the mhCACI procedure as a clear and systematic adaptation process that can be conducted within implementation science methodologies, such as the REP framework. We provide documentation tools to guide the mhCACI procedure for future interventions. The combination of the REP framework and the 10-step methodology allows for a focus on intervention content, scalability, quality monitoring, and flexibility while maintaining fidelity. Although this process was used to adapt a mental health intervention in an LMIC setting, it can be used to adapt interventions for various populations, such as ethnic minorities in HICs or humanitarian settings. With the increase in interventions that employ the concept of task-sharing (Patel, Reference Patel2012), this process also serves as an example for future interventions in LMIC settings. Although this process was used to adapt a group intervention, it is flexible enough to be used to adapt an individual intervention or even a treatment beyond mental health.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2021.5.

Data

Contact the authors for data request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Jananee Magar, Mr. Ashish Sapkota and the PM+ Sindhuli RAs and CPSWs for their support. We also want to thank the Sindhuli community members and participants of the Sindhuli PM+ trial.

Author contribution

The study was designed by BAK, MJDJ, NPL, EvO, and MS. The manuscript was drafted by MS, with support from BAK and MJDJ. MS, RG, and PG conducted the implementation of the adaptation process. MS and RG conducted qualitative interviews, coding, and analysis. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Financial support

This evaluation of Group PM+ is supported by USAID/OFDA. The trial sponsors had no role in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor the decision to submit the report for publication. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article, and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval has been received from the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) and the World Health Organization.

Consent for publication

All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study, which included consent to publish anonymous quotes from individual participants.