Introduction

Sodium chloride, or table or common salt, is a mineral that belongs chemically to the larger class of salts. It is one of nature's magical minerals since some salt intake is required to sustain body and health, making it vital in both human and animal diets (Heuberger, Reference Heuberger, Dopsch, Heuberger and Zeller1994). It is an essential ingredient for preserving food, such as pickling, flavouring, and curing vegetables, fruit, meat, and fish. Some industrial activities, including tanning, and several religious or spiritual activities, such as dehydration for mummification or desiccation, require salt (Forbes, Reference Forbes and Forbes1955: 192). Ancient oaths, proverbs (Gordon, Reference Gordon1959), and holy books use allegories related to salt; one of the most striking, for example, is the petrification of Lot's wife into salt rather than another material (Graves, Reference Graves2016: 15). Salt is used for beneficial purposes in health, and to protect from the evil eye; it also has destructive aspects, for example in the cursing and eradication of cities (Graves, Reference Graves2016: 18–22).

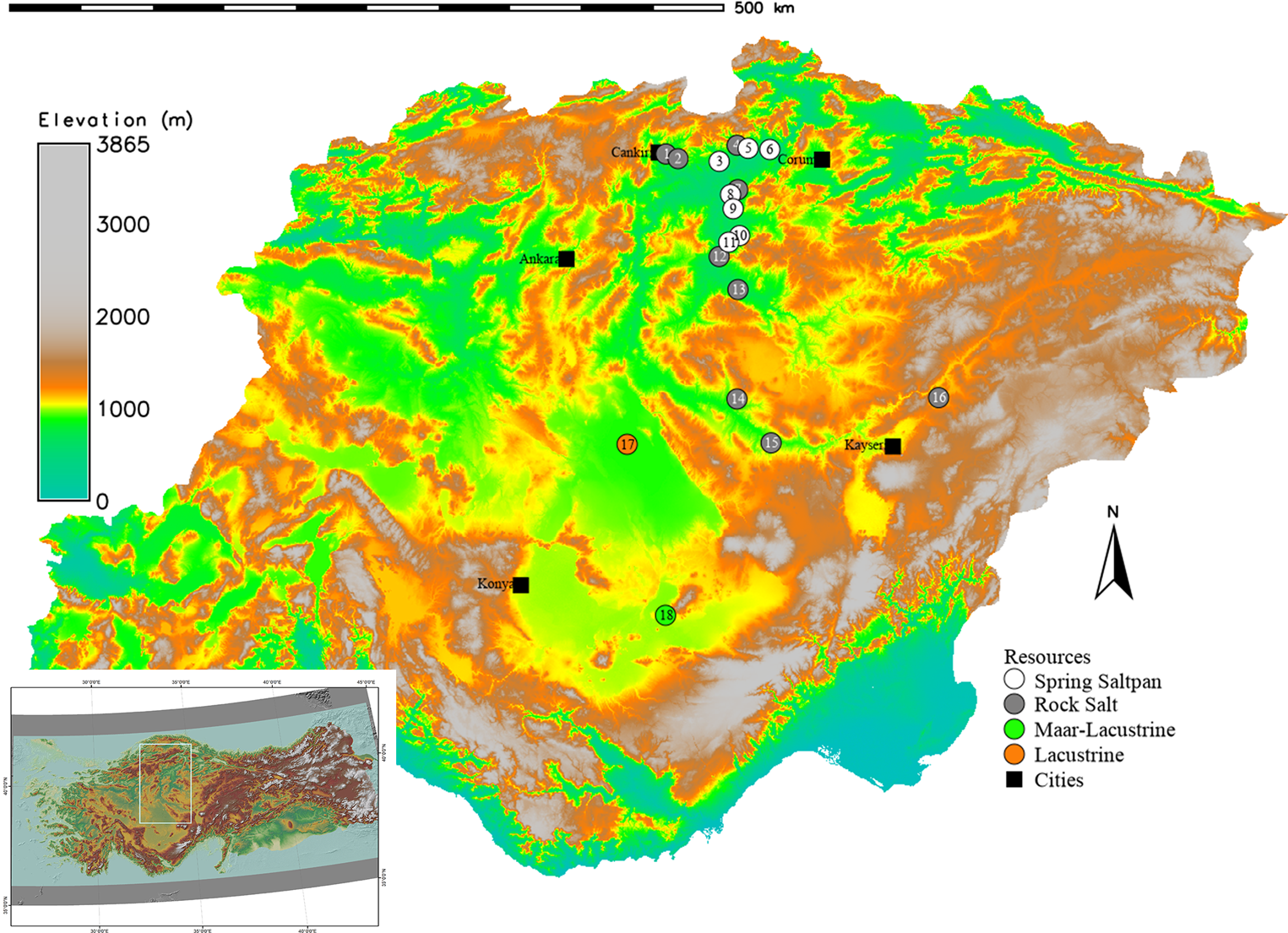

The use of salt may be assessed in several dimensions, cutting across the economic and social layers of communities. This study concerns the role that salt played between 3000 and 1730 bc in central and northern-central Anatolia (Figure 1), a topic which until recently has been little researched. This period corresponds to the Early Bronze Age (3000–2000 bc) and the Old Assyrian Colony period (c. 1950/27–1730/19 bc), when Anatolia shifted from decentralized to centralized economies and societies.

Figure 1. Map of the salt reserves in central and north-central Anatolia. Black squares indicate modern cities. Nos. 1, 2, 4, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16 (grey circles) show rock salt deposits; nos. 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, and 11 (white circles) are spring saltpans; nos. 17 and 18 are lacustrine and maar-lacustrine resources. Details are listed in Table 1.

This study combines geological, archaeological, ethnoarchaeological, and textual data including travellers’ accounts. It has three objectives: to identify the available sources of salt as well as the techniques used to obtain it; to estimate salt consumption during the third millennium bc when no textual records are available in Anatolia; and to discuss, on the basis of written sources, the economic value, transport, and people who may have been involved in salt work in the second millennium bc.

The nature and capacity of the salt reserves in central and northern-central Anatolia suggest, in my view, that the non-state ancient societies of the region had a reciprocal exchange-based social organization shaped around salt. I propose that the type of salt reserves available in Anatolia, along with the climate, provided an advantage for local communities. Thus, unlike the European and Asian examples that had specialized salt production models, or Mesopotamia's ways of controlling salt trade, salt was not monopolized and did not become a profitable resource of a centrally-controlled trade. It remained an invisible aspect of Anatolian pre-state economies.

Salt Reserves

Anatolia, in westernmost Asia, constitutes the majority of Turkey (Figure 1). The Anatolian Peninsula has abundant rock salt reserves that date to the Oligocene, Miocene, and Pliocene in the central (e.g. Çankırı, Yozgat, Nevşehir, Sivas) and eastern (e.g. Erzurum, Kars) regions. The total rock salt reserves of Anatolia are estimated to be some 5.7 billion tons (Engin, Reference Engin, Tvalchrelidze and Morizot2002). In central Anatolia, salt resources are of two types: rock salt between the strata of different geological periods, and lacustrine and spring saltpans (Karajian, Reference Karajian1920: 119; Taşman, Reference Taşman1945: 106).

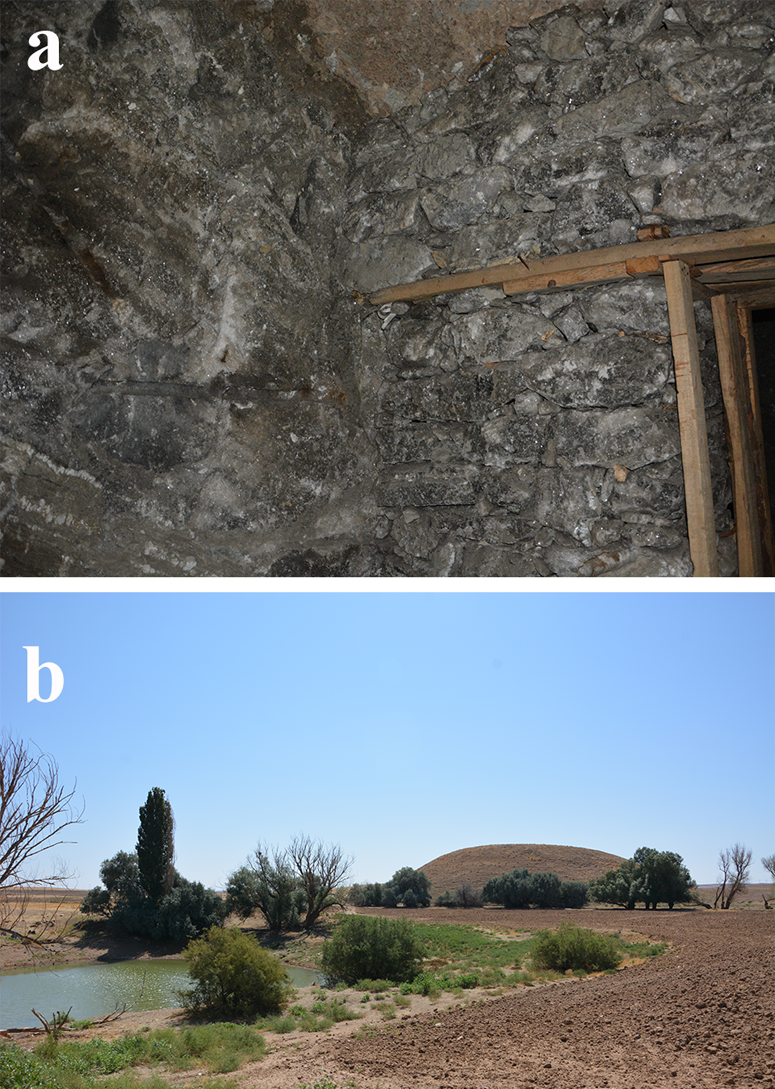

In the research area, rock salt has been found to the east of Kızılırmak, ancient Halys (Figure 1, Table 1). The Greek geographer Strabo (64/63 bc–c. ad 24) (Geography XII, 3.12, 3.37, 3.39) refers to ‘halae’ of rock salt at Ximenê, located on the Cappadocia Pontica borders in the territory of Amaseia (modern Amasya), as the namesake for the river Halys. Thus, the salt quarries in the Halys Basin were known historically, and it is likely that reserves were used in Sekili (Yozgat), Tepesidelik (Kırşehir), and Hacıbektaş (Kırşehir). To the north of Sungurlu (Çorum), the salt at Çayan has long been in use (Karajian, Reference Karajian1920: 120). To the west of Kızılırmak and the north of Ankara, the deposits of Çankırı retain their economic value to this day. The rock salt along the Çankırı–Kırşehir line is located between 800 and 1000 m asl. Among them, the largest deposit is in Hacıbektaş (Tuzköy), followed by Çankırı and Sekili; the smallest is in Tepesidelik (Barutoğlu, Reference Barutoğlu1961: 74) (Figure 2a). Tepesidelik means ‘top-holed’ in Turkish, its name deriving from digging holes to obtain salt. A recent estimate of its reserves is 20 million tons.

Figure 2. a) Salt galleries in Tepesidelik mine; b) a mound with third- and second-millennium bc archaeological material located 100 m from the entrance of the salt mine (photographs by author).

Table 1. Locations and types of salt resources in central and northern-central Anatolia.

Çankırı rock salt contains 98.34 per cent sodium chloride (NaCl), indicating its purity (Yalçın & Ertem, Reference Yalçın and Ertem1997: 214, table 5). The French geographer and orientalist Vital Cuinet (Reference Cuinet1894: 427) recorded approximately 2000 tons produced annually in Çankırı. The mines at Balıbağ (Çankırı) remain economically viable deposits. In the southern part of Kızılırmak, the mines of Palas (Yassıdağ) and Tuzköy (meaning salt village) were known since the early second millennium bc (Barjamovic, Reference Barjamovic2011). Recent research conducted at Palas demonstrates that it still contains abundant reserves (Çubuk & Baş, Reference Çubuk and Baş1999).

In Tuzköy, Karajian (Reference Karajian1920: 120) documented salt cliffs several metres high, which were also recorded in travellers’ accounts of the early eighteenth century. In the nineteenth century, Ainsworth (Reference Ainsworth1842: 178) mentions an annual estimate of 300 to 400 camel loads. Considering the average load of a camel as 400 kg, this approximates to a yearly quantity of salt of between 120 and 160 tons.

A series of spring saltpans are located near the modern town of Sungurlu (Cuinet, Reference Cuinet1894: 428–29). Some of these saltpans, such as Akçakoyunlu and Alibaba, are still exploited today due to the high quality and economic value of the salt. In all these saltpans, gathering salt crystals evaporated by the sun is still the primary method of acquiring salt. For example, the modern company Mayi Salt, located in Delice, uses former spring saltpans to trade goods from Japan to the United States. It uses natural evaporation pools exposed to the sunlight to crystallize salt out of the water (Figure 3).

Figure 3. a) Example of a small, local ‘tuzla’ (saltpan) between Yörüklü and Çavuşçu villages in Çorum, close to Resuloğlu; b) pools to transfer salty water for salt crystallization. These pools, located on land belonging to Mayi Salt, were in use until the 1960s (photographs by author).

Since solar evaporation requires an arid climate, most of the work takes place in the summer season, between June/July and September in Turkey. In some saltpans, salty water is transferred to simple, clay-walled and pebble-paved shallow pools generally 15–30 cm deep. The capacity of these pools varies from 50 to 600 m3. The water stays there for two or three days, which is long enough for the salt to crystallize. The low precipitation, strong winds, and high levels of evaporation help maintain this streamlined and expeditious processing (Yalçın & Ertem, Reference Yalçın and Ertem1997: 209).

The central Anatolian Salt Lake (Tuz Gölü in Turkish, ancient Lake Tatta) supplies a significant portion of the salt produced in Turkey, which takes place in three major saltpans in the lake. While the average chemical composition of the Salt Lake has been slightly lower, the chemical composition of the Kaldırım saltpan at the Salt Lake contains 98.96 per cent sodium chloride (Yalçın & Ertem, Reference Yalçın and Ertem1997: 214, table 5). Recently, climate change and drought have caused the lake to dry out and contamination has lowered its salt quality significantly.

Ancient writers describe the solar evaporation and high saline nature of the Salt Lake. In Naturalis Historia (book XXXI), Pliny (ad 23–79) states that, in the Phrygian and Cappadocian salt lakes, evaporation extends to almost the centre of the lakes, and the salt of these lakes is in the form of powder rather than lumps.

With respect to the difference between rock salt and salt obtained from saltpans through evaporation, the Anatolians considered rock salt to be ‘stronger’ than lacustrine or spring salt during the Ottoman period and it was cheaper (Barutoğlu, Reference Barutoğlu1961: 69). Robert James Forbes (Reference Forbes and Forbes1955: 158) drew attention to a similar taste difference between rock and sea salt, stating that rock salt has a sharper taste.

The abundance of different types of salt reserves, as well as their high quality, has attracted the inhabitants of Anatolia since prehistory (Matthews, Reference Matthews2007, Reference Matthews, Matthew and Glatz2009). Even though our current projections about past societies may not be accurate, the following provides the archaeological and ethnoarchaeological background against which I shall attempt to estimate the acquisition and use of salt in prehistoric Anatolia.

The Evidence for Salt Working

Scholars address various aspects of salt, from its location and exploitation to trade, and from its transport to the chaîne opératoire, taking economic, religious, and magical aspects into account (see Venkatesh Mannar & Gunn, Reference Venkatesh Mannar and Dunn1995: 7; Kurlansky, Reference Kurlansky2002; Harding, Reference Harding2013). Given the soluble nature of the mineral, tracking salt in the archaeological record poses a challenge.

Solid and liquid forms of salt require different methods of exploitation. The types of archaeological remains left by the techniques employed depend on the type of resource and environmental circumstances. Unless there is direct evidence for mining galleries, obtaining rock salt or gathering it from naturally evaporating saltpans leaves few archaeological traces. On the other hand, forced evaporation requires a distinctive kit: specialized clay vessels, wood, and fire. In central and northern-central Anatolia, given the finite ways in which salt can be acquired, production techniques did not undergo drastic temporal and spatial changes (Brown, Reference Brown1980: 60).

In Europe, Asia, and the Americas, the procurement of salt is detectable through certain types of salt pots known as briquetage. These simple clay containers are used to produce salt through brine evaporation, which requires heating saline water to obtain solid salt. As the process calls for the use of pottery and fire, archaeologists can expect to find pottery, tools, and wood close to resource areas (Weller, Reference Weller2015). Ethnoarchaeological (e.g. Alexianu et al., Reference Alexianu, Weller, Brigand, Curcă, Cotiugă, Moga, Alexianu, Weller and Curcă2011) and experimental archaeology also play essential roles in expanding our knowledge of the chaîne opératoire employed in salt production. Furthermore, the seasonality of exploitation, the salt miner's demography, social status, culinary habits, and the organization of trade can be apprehended not only through textual records but also through animal and human remains (Adshead, Reference Adshead1992; Boenke, Reference Boenke and Twiss2007; Flad, Reference Flad2011).

Agropastoral societies in Europe were known to have extracted salt since the sixth millennium bc, while the crystallizing and moulding of salt started during the mid-fifth millennium bc (Weller, Reference Weller2002, Reference Weller2015: 185, 189; Sordoillet et al., Reference Sordoillet, Weller, Rouge, Buatier and Sizun2018). The mining and trade of salt from the Neolithic to the Iron Age is well documented across western and eastern Europe (Stöllner et al., Reference Stöllner, Aspöck, Boenke, Dobiat, Gawlick and van Waateringe2003; Olivier & Kovacik, Reference Olivier and Kovacik2006; Nikolov, Reference Nikolov, Alexianu, Weller and Curča2011; Weller, Reference Weller, Nikolov and Bacvarov2012; Harding, Reference Harding2013; Tencariu et al., Reference Tencariu, Alexianu, Cotiuğua, Vasilache and Sandu2015; Alessandri et al., Reference Alessandri, Achino, Attema, Nascimento, Gatta and Rolfo2019). Further east, Azerbaijan and Iran have yielded evidence of salt mining dating to as early as the fifth millennium bc (Marro et al., Reference Marro, Bakhshaliyev and Sanz2010; Aali et al., Reference Aali, Abar, Boenke, Pollard, Rühli and Stöllner2012; Hamon, Reference Hamon2016), while ceramic, faunal, spatial, and ritual evidence demonstrates the production of salt within a complex social organization in prehistoric (pre-221 bc) China (Flad, Reference Flad2011). Similar research focusing on salt production and organization in the first millennium ad was undertaken in South Africa (Antonites, Reference Antonites2016).

Monopolies on salt across Europe and the Near East form the subject of several studies, including those of Adshead (Reference Adshead1992) and Mazover (Reference Mazower2000: 36), who mentions that the highland communities of the Balkans were selling snow to lowlanders in return for salt until the 1920s. The production and distribution of salt in the Maya economy provide unique perspectives on salt demand (e.g. McKillop, Reference McKillop2002; Watson & McKillop, Reference Watson and McKillop2019). The examples cited illustrate that salt, its mining, brine evaporation, and trade are topics of worldwide scholarly enquiry.

The abundant salt resources of Anatolia were a significant dietary component of people from the Neolithic onwards, when the preservation of food became a primary concern in sedentary communities (e.g. Erdoğu et al., Reference Erdoğu, Özbaşaran, Erdoğu and Chapman2003; Matthews, Reference Matthews and Hodder2005; Erdoğu & Özbaşaran, Reference Erdoğu, Özbaşaran, Weller, Dufraisse and Pétrequin2008). Salt also played a crucial role in the domestication of animals and animal husbandry. Until today, in different parts of Anatolia, salt is an essential part of the ovicaprid diet. In the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, sheep and goats are given rock salt (locally called ‘licking stones’) weekly to increase the quality and quantity of milk and meat obtained from these animals (Greaves, Reference Greaves, Engin and Helwing2014). Salt also helps to remove the animal's hide from its flesh; and the preparation of a variety of dried meats and pickles requires salt. Secondary economic aspects of animal husbandry, e.g. dye-fixing of wool or tanning, also require salt or alkaline plants (Weller, Reference Weller2015: 186). Animal herding to produce wool in Anatolia is known since the Chalcolithic (Hammer & Arbuckle, Reference Hammer and Arbuckle2018). Further uses of salt include salt-tempered pottery to keep water cool and as a coating layer for the base of ovens and rooftops (Yakar, Reference Yakar2000; Erdoğu et al., Reference Erdoğu, Özbaşaran, Erdoğu and Chapman2003: 17).

The prehistoric use of salt has remained poorly researched in Anatolia. Because the resources are easily exploitable, very little evidence is available. Textual records, ethnoarchaeological research, reports by ancient writers, as well as some nineteenth-century travellers’ accounts are used here to flesh out what Bronze Age practices may have resembled.

Previous Archaeological Research on Salt in Central Anatolia

The abundance of rock salt and evaporating spring saltpans has dominated the Anatolian salt industry for millennia. The arid climate, high summer temperatures with an average of 28oC, and winds throughout the summer season allow natural evaporation of water in lacustrine environments. This helps the spring saltpans provide easy access to salt crystals directly through dragging and gathering. This method made past societies less dependent on briquetage production and fuel. Hence briquetage was not the principal technique employed in Anatolia.

The dry climate is advantageous in terms of the time and effort required for brine evaporation. Recent research demonstrates that forty-one hours of manual labour by two individuals and sixty kilos of wood are required to obtain three salt blocks, each with a capacity approximately of 11.5 kg, via brine evaporation (Tencariu et al., Reference Tencariu, Alexianu, Cotiuğua, Vasilache and Sandu2015: 130, table 4).

The area around Salt Lake has been settled since the Palaeolithic (Erdoğu & Öbaşaran, Reference Erdoğu, Özbaşaran, Weller, Dufraisse and Pétrequin2008), although there is a marked lack of archaeological evidence for Neolithic settlements in the northern parts of central Anatolia (Matthews, Reference Matthews2007: 28, Reference Matthews, Matthew and Glatz2009). Here, the focus is on the Neolithic of central Anatolia, where access to salt is relatively easy and the types of resources required for briquetage are less essential or unnecessary. The downside is that fewer archaeological traces of salt processing are detectable in central Anatolia.

The earliest evidence of salt consumption is documented at the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük (c. 7400–6000 cal bc), where concentrated salt deposits were recovered in some food preparation and cooking areas. Salt deposits were examined around an oven, along with food preparation or cooking debris and carbonized plant remains (Matthews, Reference Matthews and Hodder2005; Atalay & Hastorf, Reference Atalay and Hastorf2006: 296, 298, table 2). Predating Çatalhöyük, the use of salt has been suggested for the late aceramic Neolithic site of Musular (c. 7600–6600 bc). The site has been associated with cattle hunting (Duru & Özbaşaran, Reference Duru and Özbaşaran2005: 23), which may have required salt to preserve the meat (Erdoğu et al., Reference Erdoğu, Kayacan, Fazlıoğlu and Yücel2007: 87).

The location of the Salt Lake and the fragmentary finds recovered at the Neolithic site of Ilıcapınar has led Ian A. Todd (Reference Todd1966: 48) to propose that salt from the Salt Lake was exchanged for obsidian obtained from Cappadocian communities. Further, a pilot study initiated in 2002 examined central Anatolian salt exploitation and trade through prehistoric times (Erdoğu et al., Reference Erdoğu, Özbaşaran, Erdoğu and Chapman2003; Erdoğu & Fazlıoğlu Reference Erdoğu and Fazlıoğlu2006). Grinding and hammering stones related to processing, by analogy with modern examples from the region, have been documented at sites like Han and Çimeli Höyük, both close to the lake.

A few sites yielding mostly Bronze Age material (e.g. Kötücük, Yavşanlık, and the Sarnıç area) located in the south-eastern part of the Salt Lake are associated with salt exploitation. Some pottery from Çimeli Höyük and İkiztepe (northern-central Anatolia) was attributed to briquetage (Erdoğu et al., Reference Erdoğu, Özbaşaran, Erdoğu and Chapman2003: 15, fig. 1: 4, 6), although the highly elaborate and fragile chalices from İkiztepe with no trace of fire are unlikely to be briquetage, and one sherd from Çimeli Höyük is too small and fragmentary to be conclusive (contra Erdoğu et al., Reference Erdoğu, Özbaşaran, Erdoğu and Chapman2003: fig. 1: 6).

Comparing the pottery that is thought to have been used as ‘salt pots’ in central Anatolia with European briquetage reveals significant differences between these assemblages and suggests that briquetage is unconfirmed in Anatolia; in my view, it is unlikely to have been used by central and northern-central Anatolian communities.

Previous Ethnological Research on Salt in the Central Anatolia

Ethnoarchaeological data demonstrate that rounded basalt blocks were used for grinding salt into powdered form. These grinders are multi-purpose and also used for grinding wheat (Ertuğ-Yaraş, Reference Ertuğ-Yaraş1997). The salt was put into leather sacks, carried and transported by camel or donkey (Ertuğ-Yaraş, Reference Ertuğ-Yaraş1997), a method of transport not unique to Anatolia, as attested in Aden, Yemen, where goatskins were transported by camels (Bowen, Reference Bowen1958: 35–6).

Ertuğ-Yaraş (Reference Ertuğ-Yaraş1997) documented a unique method to obtain salt by the villagers of Kızılkaya, located 50 km south-east of Salt Lake: villagers travelled with donkeys to the lake to fill their ceramic jugs with salty water; on their return journey, which took almost a whole day, the water evaporated, and once back home the villagers broke the jugs to obtain the salt. This type of brine evaporation requires no fuel, simply occurring while the material is being transported.

The archaeological evidence for exploitation, consumption, and trade of salt is weak in central Anatolian prehistory and no better in the protohistoric periods. For example, nothing is known about the use of salt during the third millennium bc in central Anatolia and the only evidence for northern-central Anatolia comes from the site of Çivi (Sarıiçi Höyük). The latter is located near a rock salt deposit, with evidence of rock salt mining from the Early Bronze Age until today (Matthews, Reference Matthews2007: 30, Reference Matthews, Matthew and Glatz2009).

Sarıiçi Höyük is sited on the border of northern-central Anatolia with the Black Sea (ancient Paphlagonia). Ancient Paphlagonia was an important region connecting central Anatolia and the Black Sea with the Balkans but it was also rich in raw materials like obsidian, flint, and polymetallic ores. These highly valued resources, along with salt, would have attracted settlers (Matthews, Reference Matthews, Matthew and Glatz2009: 90) and must have been integrated into exchange networks in a setting similar to that proposed for Europe (Forbes, Reference Forbes and Forbes1955: 158; Weller, Reference Weller2002). A mound near the Tepesidelik rock salt mine with third- and second-millennium bc pottery must have been linked to the nearby salt mine but requires further archaeological investigation (Figure 2b).

Surface salt is essential for grazing flocks and should be included in discussions of pastoralism, transhumance, and nomadism, which have been practised in Anatolia for millennia (Hammer & Arbuckle, Reference Hammer and Arbuckle2018). The mountainous landscape of northern-central Anatolia and its salt must have attracted pastoralists, be they nomadic or semi-nomadic. The nineteenth-century geologist William J. Hamilton, who travelled in northern-central Anatolia, recorded that he came across a small salt mine which was ‘full of herds and flocks’ (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1842: 407), indicating that salt mines were used by grazing flocks in this part of Anatolia. Bronze Age pastoralists may have followed similar practices at sites like Sarıiçi Höyük.

The profession of ‘salt-gatherer’ is documented in cuneiform tablets of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia dating to the third millennium bc (Potts, Reference Potts1997: 105). Towards the end of that millennium, salt prescriptions and the use of so-called ‘mountain salt’ is reported in Ur III textual records, prompting Daniel T. Potts, who notes specialized terms like ‘Amorite salt’ and ‘leather bag for salt’, to argue for the involvement of nomadic groups such as the Amorites in salt gathering during the Ur III period (Potts, Reference Potts1997: 105).

Estimating the Consumption of Salt

The procurement of salt through mining rock salt or gathering it from saltpans lacks concrete archaeological evidence in Anatolia. The absence of tangible remains such as ceramics, charcoal, production areas, or faunal residues prevents us from attempting any reconstruction or understanding the organization of salt production. Even the textual records of the Old Assyrian Colony period summarized below give an incomplete picture of the social organization of the salt miners or makers and do not indicate the possible extent of salt consumption.

It is nevertheless possible to estimate consumption by relying on calculations related to population density at specific periods in certain regions. Potts (Reference Potts1984) did this successfully for Mesopotamia. He estimated the annual consumption of salt at 3.6 kg per person, based on a person's daily intake of 10 g, which corresponds to the accepted daily requirement of a human. Accordingly, 360 kg of salt is the amount necessary for a village of 100 people, a considerable amount for ancient Mesopotamian city-states (Potts, Reference Potts1984: 268; Venkatesh Mannar & Gunn, Reference Venkatesh Mannar and Dunn1995: 7). This estimate could be used as a potential model to understand Anatolian salt consumption. Here, I would like to extend Potts’ hypothesis to the data collected by the Paphlagonia and Delice Valley survey projects in northern-central Anatolia. These two projects complement each other in terms of coverage and include most of the northern-central Anatolian salt resources (Figures 1 and 4). Here, my calculations target the third millennium bc, when Anatolia has no written records and hence relies on archaeological data.

Figure 4. The salt reserves in the Paphlagonia and Delice Valley with ancient settlements. White circles represent the resources and the numbered black triangles refer to: 1) Çankırı; 2) Çorum; 3) Amasya; 4) Merzifon; 5) Kırıkkale; 6) Site Çivi; 7) Resuloğlu; 8) Boğazköy-Hattuša.

Figure 5. Views with naturally evaporated saltpans of a) the hilly flanks of the Delice Valley near Kırıkkale, source of spring salt of the modern company of Mayi Salt; b) the natural saltpan at Delice (Kırıkkale); c) the natural saltpan at Uğurluday near Çorum. Local people herd animals in these areas at certain times of the day (photographs by author).

In the Delice Valley, the Middle Holocene settlement systems were examined by survey, excavation, and GIS-based analysis (Arıkan & Yıldırım, Reference Arıkan and Yıldırım2018). A population of 115 people was estimated for every 0.35 ha of settlement area based on data collected for over two decades of systematic excavations at the Early Bronze Age settlement of Resuloğlu. The settlement's population estimate relied on the total area of habitation units and ethnoarchaeological research conducted in the Near East (Kramer, Reference Kramer1982; Zorn, Reference Zorn1994), which suggested that the basic annual dietary needs of each person require 1.36 ha of the agricultural catchment area. The Delice Valley survey modelled its total catchment area and concluded that the population of the valley was 7935 people (Arıkan & Yıldırım, Reference Arıkan and Yıldırım2018: 587, table 3); if we translate this number into the quantity of salt consumed in the valley, the consumption of salt would have been of 28,566 kg. The Paphlagonia project identified twenty-six Early Bronze Age sites in the area of the modern cities of Çankırı and Kastamonu. Roger Matthews and Claudia Glatz (Reference Matthews, Matthew and Glatz2009) published the total areas for each site, which total 30.83 ha. Assigning the same density parameters to the Early Bronze Age settlements of the region, the population would be 10,129 people, requiring 36,464 kg of salt.

Some 18,000 people are therefore estimated to have occupied the territory covered by the Delice and Paphlagonia surveys during the Early Bronze Age, corresponding to a demand for approximately sixty-five tons of salt. The needs of herd animals must have added to this (Venkatesh Mannar & Gunn, Reference Venkatesh Mannar and Dunn1995) but estimating that quantity without reliable data is problematic.

The amount of energy that the third-millennium bc societies of northern-central Anatolia spent on salt production should be much less compared to regions that use brine evaporation. The type of salt resources in the area makes it possible to save energy, most importantly wood, and makes the obtention of salt advantageous. Its Bronze Age settlers must have benefited from it as the modern settlers do today.

Hills and high plains dominate the northern-central Anatolian landscape; it is a tough but rich landscape attractive for its easily accessible raw materials that could be integrated into trade networks. Copper, for example, is abundant and comparatively easy to access, explaining its early use in the form of native copper and malachite (Wagner & Öztunalı, Reference Wagner, Öztunalı and Yalçın2000). Salt, an invisible actor, may have been part of this circulation. The availability of local sources may have prompted the communities to exploit more salt for trade and exchange among the socio economic activities of the third-millennium non-state societies of northern-central Anatolia (Dardeniz & Yıldırım, Reference Dardeniz and Yıldırım2022) (Figure 5).

This assessment of salt consumption in northern-central Anatolia in the third millennium bc implies an immense circulation. If we take the figure obtained for the exploitation and consumption of salt in this rural part of Anatolia to estimate the quantity of salt required in Anatolia overall, the number would reach hundreds of tons. Although little information is available on the settlement hierarchy in northern-central Anatolia, it is possible that there was scant or no control over the organization of salt procurement. Furthermore, the patchy distribution of the deposits would have made control by a chief or ruling group difficult.

In hierarchical systems, human groups tend to develop cooperation and management strategies (Stewart, Reference Stewart2000). The small and dispersed sites and the rural nature of the settlements in northern-central Anatolia suggest a lack of hierarchical systems; instead, independent producers and suppliers roamed the landscape. As the Delice and Paphlagonia data indicate, the wide variety of natural sources and the low operational costs to acquire them could support independent producers. Communities living by salt sources must have exploited salt for their own use and exchanged it with neighbouring communities in return for other goods (e.g. grain, obsidian, metal). Moreover, the mining or harvest of salt may have been integrated with other activities.

In northern-central Anatolia, herding, exploiting metals, and quarrying precious and semi-precious stones constitute a harmonious set of activities suited to the diversity of the landscape and its natural resources. I propose that during the third millennium bc salt was likely to have been exploited and used for low-level consumption and small-scale, community-driven regional exchange. Given that (semi-) nomadic pastoralist groups were present in the region, it is possible that a heterarchic structure was present in the region and that it operated a community-based economy (e.g. White, Reference White, Ehrenreich, Crumley and Levy1995).

Textual Evidence

Textual records of the second millennium (c. 1950–1200 bc) describe salt in different contexts and shed light on various social and economic aspects of salt in Bronze Age Anatolia. Here, I use textual records of the Old Assyrian Colony period (c. 1950/27–1730/19 bc) to examine the consumption and organization of salt, leaving aside the written records of the centralized state economy of the Hittite period (c. 1650–1200 bc) as it is beyond the scope of this study.

The Old Assyrian Colony Period

The Old Assyrian Colony period (c. 1950/27–1730/19 bc) witnessed extensive international trade between Aššur and local Anatolian kingdoms documented in approximately 23,000 cuneiform tablets discovered at the capital city, Kültepe–Kanesh Karum (Kayseri). In this period, both Anatolia and Mesopotamia accumulated wealth through the commerce of metals (tin, copper, silver) and textiles. The cuneiform tablets written in Akkadian give the earliest information about the Anatolian salt economy.

The Akkadian word for salt is ṭabtu. Its trade by the Assyrians appears to be in small quantities, although more copious amounts may have been traded in an Anatolian network (Dercksen, Reference Dercksen2004: 183; Barjamovic, Reference Barjamovic2011: 14). Salt is mostly mentioned in cost lists, although it is not highly priced as it was so abundant in Anatolia (Öz, Reference Öz2011: 311). It was sold using the šeqel, which is equal to approximately 8.25 g of silver (Dercksen, Reference Dercksen1996: 81).

Donkeys were used to transport salt. A business letter (I 537: 17–20) reports carrying salt with six donkeys to a city called Elmelme (Veenhof, Reference Veenhof2008: 118). Donkeys were known to have carried a total of approximately 72.5 kg, consisting of two sealed saddlebags and a smaller top-pack. If only salt was carried with six donkeys, this would amount to 435 kg of salt, enough for 100–120 people for a year.

In a debt certificate (Kt o/k 76), salt was weighed in sìla, a standard volume of approximately one litre. A cup called a karpatum was used for measuring salt, indicating that it was ground to a certain size (Albayrak, Reference Albayrak2006: 27–8; Öz, Reference Öz2011: 312). In another tablet (Kt 92/k 247), salt was weighed with a nabīt, thought to be a cup with a 30 l capacity (Veenhof, Reference Veenhof2010: 172). So far, the archaeological counterparts of karpatum or nabīt pottery cups have not been identified with confidence.

The Kültepe tablets also provide insight into the professions of people involved in trading activities. ‘Salt dealer’ (ša ṭabtim) appears in some records, among other professions such as blacksmith, boatman, brewer, scribe, and priest (Veenhof, Reference Veenhof2008: 118, n. 528). The title ‘chief of salt dealers’ (rabi ṭābātim) is documented (Kt. 97/k 149) in the archive of an Assyrian trader (Çayır, Reference Çayır2013). This tablet reports the sale of a female slave; it was sealed by six witnesses, one of which had the designation ‘Dumana, son of Kamana, chief of the salt dealers working under rabi sikkitim’ (Çayır, Reference Çayır2013: 306–8). The exact role of a rabi sikkitim in the palace is unclear, but the existence of a seal impression with the title rabi ṭābātim not only implies a degree of control over salt but also hints at the involvement of salt dealers in a hierarchical system.

During the Old Assyrian Colony period, the different levels of production, organization, distribution, and control of salt may be inferred from the titles of palatial officers, which support John Stewart's (Reference Stewart2000) argument of management in hierarchical systems intended to encourage cooperation and prevent cheating. Salt dealers and their overseers were controlled by a palace officer, which indicates control over commodities, even if they were abundant and low-priced. The salt dealers and their superiors must have collaborated to meet the demands of the palace while preventing cheating by maintaining a rigid hierarchy over production and distribution.

Conclusions

Anatolia had a simple salt production system. The abundance of salt in the form of rock salt and evaporated saltpans allowed communities to obtain it without depleting the resource. The mining of salt from rocks or seasonal harvest from saltpans provided people with adequate amounts of salt as it does today.

While the production of salt via the briquetage technique leads to some complexity in governance and social organization in different parts of the world (e.g. Europe, China), starting in the Neolithic Anatolians obtained their salt from local resources, suggesting that control over salt cannot have been an essential basis for social and power differences.

The present study, based on projections of salt consumption in two regions, Delice (Çorum) and Paphlogonia, highlights that large quantities of salt were used by human populations during the third millennium bc. Archaeological evidence does not provide solid data for a centrally controlled system for the gathering and distribution of this mineral during this period, unlike the contemporary Mesopotamian economies, which strongly rely on palatial control over salt (Potts, Reference Potts1984, Reference Potts1997).

For the early second millennium bc, I argue that a scheme analogous to that of the previous period reflects the organizational pattern in Anatolia. During the Old Assyrian Colony period, salt was gathered and distributed within the region. While textual records confirm the importance attributed to this mineral, and the existence of certain personages responsible for its circulation, specialized salt production and trade networks shaped around it appear to be missing.

In Europe, control over copper and salt and their trade were crucial for the Bronze Age economy (Kristiansen, Reference Kristiansen, Kiriatzi and Knappett2017: 158). In Anatolia, the written records indicate a certain amount of control over salt during the Old Assyrian Colony period, in order to guarantee the amount required for palatial consumption. The trade of salt in small quantities and the presence of professions like ‘salt dealer’ and ‘chief of salt dealers’ reflect the monitoring of salt, yet the exact palatial involvement in this trade is unknown. The most critical parameter must have been transport from the source to dealers for further distribution (to the palace, elites, other cities) through the well-established trading networks of the period (Dercksen, Reference Dercksen1996, Reference Dercksen2004). Salt was never part of the prestige goods economy or a source of wealth accumulation such as silver, copper, tin, and wool, as documented by the price lists.

While aware that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, I maintain that there are no grounds to argue for specialized salt production during the third and early second millennia bc in Anatolia. It is likely that local people gathered salt for domestic consumption and community-driven exchange. While textual data document the use of salt in various social contexts, it was not a strategic mineral. While salt was important for humans and wildlife, its abundance and availability meant that access to or control over it is unlikely to have played a major economic role in the Bronze Age in Anatolia.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of Istanbul University (Project no: SBA-2021-37596). It was also supported by the BAGEP Award of the Turkish Science Academy. I express my gratitude to Roger Matthews for sharing images of Çivi, to Bülent Arıkan for his support with the maps, and to Mustafa Demirbilek for allowing me to enter the salt mines in Tepesidelik. My special thanks go to Oktay and Sibel Gözüyukarı, who provided me with all the necessary information and documentation of their company along with great hospitality.