Modern economic growth is closely related to the success of industrialization.Footnote 1 Latecomers endeavored to emulate the first movers, applying and adapting their production methods and industrial organization. At the time of the Second Industrial Revolution, the automobile industry played a decisive role, because its backward linkages favored a broad spectrum of manufacturing activities, a factor highlighted by prominent business historians.Footnote 2 Creating a motor industry was a strategic objective for many countries that wanted to industrialize.Footnote 3

The aim of this article is to compare the evolution of the automobile clusters of Barcelona (Spain) and São Paulo (Brazil) from when they were formed to when they moved beyond their infant industry phase at the beginning of the 1970s. Following Porter, we consider a cluster to be a “geographically proximate group of interconnected companies and associated institutions in a particular field, linked by commonalities and complementarities.”Footnote 4 The Barcelona cluster includes the companies and institutions located in its province. Those in São Paulo include the capital of the state of the same name, plus areas around the Anchieta Highway (which links the city with the Port of Santos) and around the Dutra Highway (which connects with São José dos Campos, 85 kilometers from the center of São Paulo, and then continues up to Rio de Janeiro). These two metropolitan regions are considered to represent case studies of relatively early industrial development in developing countries. Although the Industrial Revolution failed overall in Spain, Catalonia is an example of early industrialization in southern Europe.Footnote 5 Similarly, São Paulo stands out as one of the few industrial systems of the Southern Hemisphere.Footnote 6 In both cases, manufacturing success was preceded by several decades of capital accumulation and the growth of business capabilities associated with exporting primary goods with a highly inelastic demand. In Catalonia, it was wine-sector products; in São Paulo, it was coffee. For both, agriculture was the main industry starting in the eighteenth century and nineteenth century, respectively. The exchange of wine-based products continued to favor the conversion of Barcelona into the main cotton-spinning center of Mediterranean Europe throughout the 1800s. In the capital of São Paulo, the industrialization process increased at the end of the nineteenth century, stimulated by the abolition of slavery in 1888, the reinvestment of profits from coffee exports, and the search by importers for alternative domestic supplies. The Great War strengthened the import-substitution process. During the 1920s, São Paulo experienced spectacular industrial growth through its coffee exports.

The automobile industries reached important milestones in the hinterlands of both cities at the beginning of the twentieth century, although not enough to make them comparable with the pioneering automobile centers of Michigan, the West Midlands, Île de France, and subalpine Italy. The success of automobile manufacturing in Barcelona and São Paulo was not obvious until the 1970s, when both districts were recognized as prominent centers of this industry. While the motor industry has experienced a considerable decline in Detroit, Coventry, Paris, and Turin, its health is relatively robust in São Paulo and Barcelona.

This article analyzes the process that converted these two cities into important capitals of the car world of the Mediterranean and Southern Hemisphere, and the role the auto industry played in the industrialization of Brazil and Spain. In both countries, the auto industry experienced considerable regional concentration during the first three quarters of the twentieth century. It is no accident that in 1974 São Paulo accounted for more than 90 percent of all vehicles manufactured in Brazil, while Barcelona was responsible for almost 50 percent of those produced in Spain. We explore four possible factors that explain the success attained in both regions: (1) the presence of external economies, (2) the capacities provided by hub companies, (3) the adoption of national government strategic industrial policies, and (4) the emergence of adequate local institutions. The importance of each of these factors in the decisive phases that enabled the industry to reach maturity is considered.

In studying the industrial districts of the United Kingdom at the end of the 1800s, Alfred Marshall offered a coherent interpretation of the external economies arising from the geographic concentration of an industry. He indicated the abundance of skilled workers, the presence of related industries, and the relatively free circulation of knowledge within the district as key, although not exclusive, externalities.Footnote 7 Since the end of the twentieth century, authors in Latin countries such as Italy and France insisted on the benefits of a geographically concentrated industry, pointing out competitive advantages of small- and medium-sized firms and the existence of institutions that favor cooperation within districts.Footnote 8 However, these works tend to undervalue the role played by a large company as the backbone of the district.Footnote 9

Perspectives focused more on the history of business, such as those of Landes, Chandler, Tolliday, Klepper, and Lazonick, insist on an increase in efficiency arising from size. They underline that large companies in industrialized economies played a central role in the success of the Second Industrial Revolution through their accumulation of technological, organizational, distribution, and marketing capabilities, among others.Footnote 10 Evolutionary economics also emphasize the potential of large companies with significant economies of scale and considerable research and development (R&D) expenses to lead industrial development in sectors.Footnote 11

Although output of large production companies was based, as indicated by Chandler, Lazonick, Tolliday, and Amatori, on the considerable use of semiskilled workers in factories with significant machinery, it also required more managers who needed to be trained.Footnote 12 Established capitalist industrial companies used their competitive success to efficiently exploit economies of scale and scope internal to the company,Footnote 13 but this did not prevent them, as also pointed out by Chandler, Amatori, and Hikino, from organizing networks of clusters with their auxiliary industries and strategic suppliers.Footnote 14 This is consistent with the tendency of the automotive industry to concentrate at regional levels.Footnote 15

Markusen analyzed three types of industrial districts (hub-and-spoke, satellite platforms, and state-anchored) that all revolve around big companies.Footnote 16 In the most common, the hub-and-spoke districts, a few large firms act as coordinating centers or hubs in their regional economy. This focus fits well with Porter’s theory on clusters: clusters act as a key source of competitive advantage globally that, unlike the Italianate district, do not require a certain size of company to obtain the benefits of a geographically concentrated industry. Footnote 17

The government can likewise influence the creation of competitive advantage by applying strategic industrial policies.Footnote 18 Gerschenkron, Chang, and Shapiro, among others, noted the tendency toward growing government intervention in developing economies with the aim of catching up with the first comers. Footnote 19 Chang used the argument presented by Hamilton and List in defense of the infant industry.Footnote 20 Chang reiterated that the transition toward activities with greater added value did not always occur spontaneously. A substantial number of developing countries adopted a wide range of strategic industrial, commercial, and technological policies. The need for the governments of developing countries to move away from pure laissez-faire policies and toward industrial development with efficient incentive systems is shared by a number of authors.Footnote 21

For many economic historians, the quality of institutions has been key to the success of modern economic growth.Footnote 22 North and Mokyr indicated that the institutional structure of incentives was a decisive variable in the gestation and spread of the first Industrial Revolution. Acemoglou and Robinson underlined the prevalence of nonextractive institutions in the West as crucial for long-term development.Footnote 23 Eichengreen pointed toward the institutions that favored cooperation after World War II as key to the golden age of growth.Footnote 24 In the Italian or neo-Marshallian perspective, institutional environment was also indicated as a central element of competitive advantage.Footnote 25 Brusco similarly favored the system of industrial relations of Emilia-Romagna, which ensured that increased local salaries and increased productivity went hand-in-hand, and considered this to be a main factor in the district’s competitive advantage.Footnote 26 According to this theory, which Zeitlin called neo-Marshallian, cooperative attitudes occurred in the districts of small- and medium-sized companies.Footnote 27 The companies in these districts would moreover increase their competitiveness, thanks to access to public or quasi-public goods, such as infrastructures, education, technology centers, and specialized financial institutions.Footnote 28

This article assesses the roles played by external economies, leading companies, national government industrial policies, and local institutions to explain the establishment of automobile industry clusters in Barcelona and São Paulo. The next section analyzes the origins of both clusters. The keys to their success, which took place between the beginning of the 1950s and the 1970s, are subsequently studied. Finally, conclusions are presented.

The Slow Emergence of the Cluster: External Economies, Leading Companies, and Local Institutions, 1900–1950

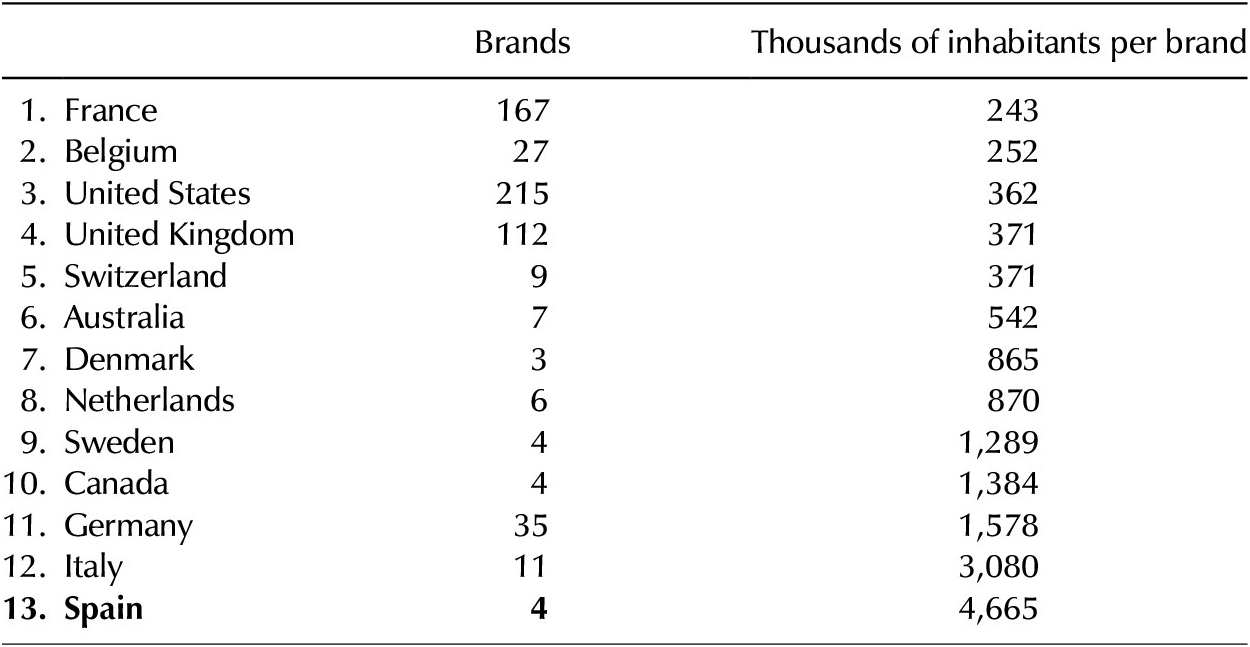

The number of owners per automobile firm can be used as an initial indicator of the degree of development achieved by the automobile industry at the beginning of the twentieth century. This ranking, shown in Table 1, was led by France and Belgium, with around 250,000 owners per firm in 1901. A second group of countries, in a region with 370,000 inhabitants, was formed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland. Three countries with small populations—Australia, Denmark, and the Netherlands—had between half a million and a million inhabitants. Sweden, Canada, and Germany had firms for between 1.2 and 1.5 million inhabitants, while Italy had one automobile firm for every 3 million inhabitants. Note that Spain was also fairly limited, with only one firm per 5 million inhabitants. Brazil does not even appear on the list.

As suggested in Table 1, the automobile industry in Spain, with only four indigenous firms in 1901, was far smaller than in industrialized countries. However, three of these four manufacturers set up their businesses in Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia, a region that at the time had around two million inhabitants. The nearly seven hundred thousand inhabitants per manufacturer indicates that there was already an interest in Barcelona for a relatively new industry. This was not yet the case in São Paulo, which only had five automobiles registered in 1901.Footnote 29

Table 1 The automobile industry in 1901: number of local brands and inhabitants per brand

Source: Brands from Catalan, “The Life-Cycle of the Barcelona Automobile-Industry Cluster, 1889–2015,” 77–124. Population from Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy 1820–1992.

Although the industrial engineer and textile entrepreneur Francesc Bonet built an initial internal combustion automobile in Barcelona in 1889, the cluster did not begin to germinate until the end of the century. In 1898, the lieutenant colonel and electrical entrepreneur Emili La Cuadra set up a new firm with the aim of manufacturing automobiles. After hiring the young Swiss engineer Markus Birkigt, La Cuadra was capable of manufacturing around five vehicles, but it went bankrupt one year later. However, both its facilities and its designs were used by its successor, the company of J. Castro, in which Birkigt remained as the main engineer.Footnote 30

In 1904, a group of Catalan industrialists led by Damià Mateu and Markus Birkigt established Hispano-Suiza. The lightness and durability of the engines designed by the Swiss engineer allowed the company to export its first production licenses in 1907. Seeking to expand its activity, Hispano opened an initial agency in Paris in 1911 and built its own factory two years later. In 1915 Hispano-Suiza was capable of winning, with a light engine designed in Barcelona, the French government tender to equip its warplanes. The aircraft engines produced during World War I with Hispano-Suiza’s technology made profits surge for the Barcelona company.Footnote 31

Together with Hispano-Suiza, other manufacturers appeared in Barcelona before the Great War. The interruption of imports during the conflict motivated modest local entrepreneurs to embark on the handcrafted production of automobiles, although the majority had an ephemeral lifespan.Footnote 32 The most prosperous initiative was that of Arturo Elizalde, originating in 1909, when this industrialist, of Cuban-Catalan descent, opened a workshop to supply and manufacture components such as crankshafts, valves, differentials, and bumpers. He launched his first car in 1913 and tried to follow the path traced by Hispano-Suiza, producing luxury cars and their engines until 1927.

After ruling out Barcelona because of its high rate of labor disputes, in 1920 Ford established a plant in the free Port of Cadiz, on the Spanish southern Atlantic coast.Footnote 33 However, in the middle of 1923 Ford decided to move to Barcelona, after noting the difficulties of operating in the Andalusian port, where the production rate, set at five thousand vehicles per year, hardly succeeded in reaching one thousand units.Footnote 34 The weight of the completely knocked down (CKD) kits assembled in Barcelona increased sevenfold between 1927 and 1929, and were exported in part to Italy, North Africa, and Portugal. Footnote 35 In turn, Ford’s employees totaled 494 in 1929. Ford’s competitive prices seriously affected the local manufacturers, intensifying the drastic reduction in profits suffered by Hispano-Suiza, and forcing Elizalde to abandon the production of automobiles in order to concentrate on aircraft engines.Footnote 36

Ford’s decision to move to Barcelona is proof of the possible existence of a district. Barcelona, like Cadiz, had similar advantages in its free port area, but could also provide the classical Marshallian externalities, which the Andalusian port lacked: trained workers, specialized suppliers, and a climate of diffuse knowledge of the world of automobiles.Footnote 37 Another proof would be the emerging institutional fabric, which disseminated knowledge and, thereby, accompanied the development of the district. Important institutions included the Chamber of Commerce, whose main mission was to defend protection as a tool of industrialization; the Escuela Industrial, which trained entrepreneurs and skilled technicians; and the Escuela del Trabajo, which since 1907 had a specific department to train machine operators. The sector’s first specific institution was the Real Automóvil Club de Cataluña, created in 1906, which organized the first automobile exhibition in 1913. In 1919, the first Automobile Fair of Barcelona was organized, exhibiting automobile products from fifty-eight Spanish and foreign companies. At the fourth fair, held in 1925, 408 companies from the sector were present.Footnote 38

The outbreak of the Great Depression significantly affected the trade balance of Spain. To curb the imbalance, the provisional government of the republic, proclaimed in April 1931, was forced to increase tariffs and introduce quotas on the importing of many products, including automobiles. However, before the end of the year, it established tariff reductions on the importing of components and parts, provided that the percentages of domestic content in the cars assembled increased. Although the local manufacturers were languishing compared with foreign subsidiaries, the auto components industry was able to progress and employed four thousand people by 1935. When the Civil War broke out in 1936, approximately half of the components used by Ford were manufactured in Barcelona. Footnote 39

Following the pattern of the rest of the European subsidiaries, during the Great Depression, 40 percent of the capital of Ford’s Spanish subsidiary became locally owned, being transformed into Ford Motor Ibérica (FMI). After Dagenham, FMI was Ford’s European subsidiary with the highest profit in 1935.Footnote 40 At the time, Ford employed 750 people in Barcelona, while its suppliers already employed a further twenty-five hundred people. The progress made by the Catalan subsidiary encouraged Ford to plan the construction of a bigger factory. The project, ratified on May 5, 1935, was frustrated by the military uprising in July 1936.Footnote 41

The military uprising also prevented General Motors (GM) from building a big factory in Barcelona. Like its neighbors in Dearborn, the company from Flint had likewise initially chosen Andalusia (Málaga) to establish its subsidiary in Spain, although in 1927 they transferred it to Madrid. Five years later, General Motors Peninsular (GMP) relocated again, this time to Barcelona, where it assembled Chevrolets and other models until 1936. When the Civil War broke out, GMP was also planning the construction of a new factory in Barcelona, where it intended to assemble twenty thousand cars per year, of which 70 percent would be for export. Footnote 42

The war ended on April 1, 1939, with the victory of General Francisco Franco, who remained as head of the Spanish state until his death on November 20, 1975. Both GM and SIAT—a company in which Fiat, among others, was a shareholder—sent proposals to the new government to build assembly plants in the industrialized territories of Spain, Catalonia, and the Basque country. None was accepted by the new regime.Footnote 43 At the end of 1939, the Ministry of Industry limited the foreign ownership of Spanish companies to a maximum of 25 percent. In September 1941, the Spanish government created a public holding company, the Instituto Nacional de Industria (INI), the mission of which was to encourage industrial autarky. In 1946, the Catalan factory of Hispano-Suiza was sold by the then owner and former Francoist mayor of Barcelona, Miguel Mateu, to the INI. The Hispano-Suiza factory became part of the INI subsidiary, Empresa Nacional de Autocamiones S.A. (ENASA). The main objective of this publicly owned company was the construction of a modern truck factory in Madrid, which would benefit from the technical knowledge accumulated in the Barcelona plant and be managed from the capital of Spain.

Unlike GM, Ford did not abandon Barcelona at the end of the Civil War. However, the profits of this subsidiary never reached their prewar levels. The marked underutilization of the Barcelona factory explains why the number of employees went down drastically, having dropped to just 293 workers in 1942.Footnote 44 FMI barely manufactured one thousand trucks between 1945 and 1949, a volume that could not offer profitability. Finally, in 1954 Ford ended up doing away with its Spanish subsidiary, which became Motor Ibérica (MI), funded with local capital. Dearborn also disposed of its facilities in other countries whose industrial policy tended to be considered as excessively nationalist, such as France and India. Footnote 45

The ravages of the Franco regime radically transformed the Catalan cluster. The Automobile Fair of Barcelona did not open again until the 1960s. The renowned luxury automobile brand, Hispano-Suiza, became a second-rate player depending on a public company run from outside the district. The Ford subsidiary had become a Spanish private company without its own technology, which struggled to produce light commercial vehicles and agricultural tractors. Mass production had not yet reached Barcelona. However, despite the difficulties, in 1950 the Barcelona district was home to 131 factories and workshops producing components such as engines, pumps, distributors, headlights, cylinders, carburetors, and ball bearings.Footnote 46

The origins of the São Paulo cluster are fairly different from those of the Barcelona cluster, due to much greater initial delay. Brazil was the last American country to end slavery, the process being delayed until 1888. The capital accumulated by the wealthy coffee estate owners from the interior of São Paulo state sustained the commercial and industrial growth of their capital, together with some importers from the end of the 1800s. In the first decade of the twentieth century, we already have records of the existence in the capital of São Paulo of some 326 industrial companies employing some twenty-four thousand manufacturing workers.Footnote 47 These companies included shipyards, several steam-machine manufacturers, and agricultural equipment and transport material manufacturers.

In 1901, there were only five automobiles registered in São Paulo, but five years later the figure had risen to 84.Footnote 48 It was the drivers of the imported cars who fostered the dissemination of the first automobile knowledge in the region.Footnote 49 In 1904, the company Luiz Grassi & Irmao Indústria de Carros e Automóveis was founded to build and repair horse-drawn carriages, and in 1907 it assembled its first Fiat car.Footnote 50 However, above all, the small repair and part-manufacturing workshops were the origin of the São Paulo cluster. They arose to serve the spare parts market of a vehicle pool that, in the state overall, increased from six thousand to seventy thousand vehicles during the 1920s.Footnote 51 In 1927, the São Paulo firm Souza Noschese managed to build the first internal combustion engine that used materials entirely of Brazilian origin.Footnote 52

Following the expansion of the market and the availability of specialized suppliers and labor, Ford, GM, and International Harvester installed their first factories in São Paulo. As in Barcelona, it was less costly for them to import dismantled cars. Ford inaugurated its assembly line in January 1920, taking advantage of facilities leased in Praça da República, in the heart of the city. A few months later, it built a new factory in the Bom Retiro neighborhood.Footnote 53 In 1925, its output reached 14,861 vehicles, while sales rose to 24,500 units.Footnote 54 In January 1925, the other Michigan giant, GM, inaugurated its factory in the Ipiranga neighborhood, the industrial heart of the city. According to the company itself, its decision to set up in São Paulo arose from a study performed by the management on the viability of the location.Footnote 55 The GM executives indicated especially the availability of electric energy, oil, raw materials, and parts and components for the repair market. In 1927, after having assembled twenty-five thousand Chevrolets, General Motors do Brasil began to build a new factory in São Caetano do Sul, a municipality crossed by the main road and the railway that link the Port of Santos with the state capital. Inaugurated in 1929, its six hundred workers were three times those of Ford.

The big tire companies had also set up in Brazil, attracted by its abundant reserves of raw material. During the second decade of the twentieth century, they began to establish themselves in Rio de Janeiro. However, they soon understood that São Paulo was a better option, because it enjoyed the advantages associated with a geographically concentrated industry. Between 1923 and 1929, Pirelli, Firestone, Goodrich, and General Tire opened plants in the industrial capital of a country whose rain forest contained a generous supply of the key raw material for their activity.Footnote 56 Henry Ford’s dream of colonizing the Amazon, promoting plantations of Hevea brasiliensis from Fordlândia and Bellterra, was less successful. These experiments ended up failing, not having paid sufficient attention to the environmental conditions of tropical ecosystems.

In 1928, the number of industrial establishments in São Paulo had risen to 9,603, overall employing some 150,000 people who contributed 37 percent of Brazilian industrial production. Among those companies, 317 establishments were already devoted to the construction of transport material and employed some five thousand workers.Footnote 57 The car-body manufacturer Grassi, established in 1920, was especially important. At the end of the decade, it was building its own buses and supplied around sixty bodies a day for the trucks and buses of Ford and GM.

There, south of the equator, as on the banks of the Mediterranean, various institutions endeavored to support the motorization of São Paulo. The first car race of Latin America was held in the city on July 26, 1908. It was organized by the Automobile Club of São Paulo, founded 15 days earlier.Footnote 58 Ten years later, under the patronage of the state government, the I Congresso Paulista da Estradas de Rodagem took place, when the work building the main Santos–São Paulo main road, which began in 1913, was almost completed.Footnote 59 Furthermore, the First Automobile Fair of São Paulo was held on October 13, 1923, with five fairs being held across the decade.Footnote 60 As for educational institutions, the opening of the mechanic schools of Ford and GM stands out, because they trained workers both for the assembly line and for after-sales services.Footnote 61 Finally, apart from the automobile industry, the establishment of the Centro das Indústrias do Estado de São Paulo in March 1928 was especially important. For the first time, this was an organization that had a clearly protectionist discourse.

As in Iberia, the assembly establishments that Ford also inaugurated in Recife (1925), Porto Alegre (1926), and Rio de Janeiro (1927) were unsuccessful. Footnote 62 This would indicate the lack of Marshallian external economies, which were, on the contrary, already present in the capital of São Paulo. The case of General Motors do Brasil (GMB) ratifies this hypothesis, given that the company’s own management maintains that the choice of São Paulo for its Brazilian establishment was linked to the area being the main industrial hub of Latin America. Footnote 63

The big U.S. manufacturers not only provided the emerging district with production capabilities, promoting the assembly of their vehicles, but also transferred distribution and marketing capacities. Ford, GM, and even Studebaker created dense networks of agents, which made them into the first companies with commercial delegations throughout the country. São Paulo again won the game in this field. Studebaker had begun to operate from Rio and, in 1926, ended up implicitly recognizing the externalities of the São Paulo capital, transferring its registered offices there. Footnote 64

The outbreak of the Great Depression also considerably affected the Brazilian economy. GM, which had just opened a modern factory in São Caetano, within the ABC Region,Footnote 65 experienced a considerable contraction of demand during the Great Depression. The already low number of 4,051 vehicles assembled in 1931 dropped to just 1,566 in the following year. To ensure its survival in Brazil, GM tried to find a niche as a bus manufacturer, although its main activity until the mid-1950s ended up being the production of refrigerators. Footnote 66

The recovery of the São Paulo economy was driven above all by national capital, which built new although not very large factories. During this process, the capital from coffee tended to become less important. By 1949, São Paulo state generated around 49 percent of Brazil’s industrial added value. The share of consumer durables was even higher, reaching 72 percent of the federation’s total.Footnote 67 Brazil was mostly governed by Getúlio Vargas, whether as interim president (1930–1934), constitutional president (1934–1937) or as an open dictator at the head of the Estado Novo (1937–1945).Footnote 68

This was not a good period for U.S. transnational corporations. In 1940, GMB assembled its vehicle number 150,000, indicating an average production of just over ten thousand units per year. The situation was no better for Ford, whose production was very far from its capacity, which in theory allowed it to build around eighteen thousand vehicles a year.

The production of parts and components experienced a notable boom during the World War II, as a result of the lack of imports. When the war ended, around a hundred workshops were spread around São Paulo and its ABC region, employing some thirty-five hundred people and with a capacity to manufacture around two thousand different parts, especially components such as electric accumulators, radiators, brake disks, tires, wheel rims, axles and crowns, and pinions for gears.Footnote 69

Despite the scarce development experienced, dozens of companies produced parts and components from the end of the 1930s. New tire manufacturers, such as Goodyear (1938) and Dunlop (1939), set up in São Paulo and the Cia. Americana Industrial de Omnibus tried to promote the construction of buses.Footnote 70 The Ipiranga neighborhood attracted the company Veículos e Máquinas Agrícolas (Vemag), an initiative that included the collaboration of the hoteliers Domingos Fernandes from Rio de Janeiro, the Swedish investor Swend H. Nielsen, and the representative of Studebaker in Brazil, Melvin Brooks.Footnote 71 Vemag, which had one of the most important stocks of heavy tools in South America, assembled its first trucks—for Studebaker and Massey Harris—in 1948. Shortly afterward, it embarked upon negotiations with Scania to assemble its commercial vehicles starting from imported CKD kits.Footnote 72

As occurred in Barcelona, the São Paulo district had been capable of generating Marshallian type externalities, but had not achieved the take-off of mass production. The end of commercial restrictions, once the global conflict ended, again placed the majority of parts manufacturers in a difficult situation. Footnote 73 However, the capacities accumulated in both regions after decades of activity placed them in a position to take advantage of any favorable change of situation in order to commence this take-off. This occurred in the 1950s, when both Spain and Brazil adopted strategic industrial policies aimed at the comprehensive development of this sector. Footnote 74

The Take-Off, 1950–1973: Strategic Policies, Leading Companies, and Local Suppliers

In 1950, the production of automobiles both in Spain and in Brazil hardly exceeded a thousand vehicles a year and assembly prevailed over production in the industry. Neither of the two economies appeared on the list of the world’s first fifteen producers (Table 2). However, during the 1950s, Barcelona and São Paulo were major players in the take-off of the automobile industry in their respective countries. By 1973, Spain and Brazil were already in the tenth and eleventh positions, respectively, in world automobile production. The Catalan capital was responsible for 50 percent of Spanish production,Footnote 75 while São Paulo enjoyed an overwhelming dominance, greater than 90 percent, in Brazilian production.

Table 2 Main automobile producers (thousands of units)

Sources: Authors’ elaboration from United Nations, Statistical Yearbook; and OICA, Production Statistics.

The failure of the autarchic project obliged the Franco regime to modify its economic approach in 1948. The INI ended up approving the project led by Banco Urquijo to produce passenger cars, under license from Fiat, in the Zona Franca of Barcelona. However, it insisted on being the principal shareholder. The Sociedad Española de Automóviles de Turismo (SEAT) was established in 1950, its strategic shareholders being the public holding company INI (51 percent), Banco Urquijo (7 percent), and Fiat (7 percent).Footnote 76 In return for operating in a closed market with hardly any competition, SEAT was required to use high percentages of domestic content. Its first model, the SEAT 1400, was launched in 1953 and one year later already contained 60 percent of locally produced components.Footnote 77

Fiat had, indeed, unsuccessfully attempted to set up in Spain since 1931, and its experience, like that of Ford in 1923, demonstrates the difficulties of operating in settings without a sufficient industrial base. A few months before the proclamation of the republic, Fiat took control of the Hispano Fábrica de Automóviles y Material de Guerra, a subsidiary of Hispano-Suiza established to please King Alfonso XIII, in Guadalajara, a province adjacent to Madrid.Footnote 78 The subsidiary never obtained good results, hindered by the lack of knowledge, labor, and local suppliers in inland Spain. Finally, it ended up transferring the assets of the land vehicle section to the Italians, who began to prepare the assembly of the Fiat 514. Evidence shows that, in Guadalajara, they only manufactured the bodywork structure, made from beechwood that was then lined with metal sheets imported from Italy, where the engines, axles, and gearboxes were also produced.Footnote 79 Finally, in December 1935, after having assembled fewer than three hundred cars in four years, Fiat decided to liquidate and wind up its Castilian subsidiary.

In 1943, Fiat sent its engineer Giuseppe Corziatto to Spain to assess a possible return. Accompanied by the INI engineer Sánchez Bautista, Corziatto visited forty-one establishments located in the so-called northern region, mainly the Basque country; fifteen in Barcelona; and ten in inland Spain, all in Madrid except for one in Valladolid. Concerning Barcelona, the Fiat engineer laid particular stress in his report on the parts cast by the company Dalia, the fuel pumps and distributors for the engine ignition of Auto-Electricidad, the headlights of Artés de Arcos and of Biosca, and the parts for brakes and clutches of Industrias Cabré. He also indicated that Ford commissioned the production of all the parts of its three-ton truck from companies in the district, with the exception of the powertrain and the drive axle. In his conclusions, Corziatto maintained that the difficulties surrounding production in Spain would be greatest in Madrid, considerably reduced in Catalonia, and even more so in the Basque country. However, the negotiations with the INI broke off in that same year and were not taken up again until January 1947.Footnote 80

At the end of 1948, Suanzes, president of the INI, announced the choice of Barcelona as the location for the future joint venture, justifying it on the basis of the abundance of both suppliers and workers. In 1950, there were 433 automobile part workshops and factories registered, of which 30 percent were in the province of Barcelona, 21 percent in Biscay, 13 percent in Guipúzcoa, and 11 percent in Madrid. Although there are no reliable data on the number of employees, the evolution of metallurgy workers can serve as an indicator. In the city of Barcelona, these increased from 10,588 in 1905 to 56,890 in 1950, in addition to workers in the surrounding towns, which were already important metal processing centers, such as L’Hospitalet, Cornellà, and Sabadell.Footnote 81

In 1957, SEAT launched the 600 model. This was not only the first mass-produced car manufactured in Barcelona, but also 97 percent of its components were locally produced.Footnote 82 The launch of the 600 allowed SEAT to increase its production volume tenfold between 1961 and 1974. The output of the 600 model increased from twelve thousand units in 1958 to eighty thousand units in 1970. The overall production by SEAT exceeded 100,000 cars per year in 1965 and reached 360,000 cars in 1974. Although the 600 was the model most produced during this period, having a 29 percent share of the 2.5 million cars manufactured, other models also obtained good figures, such as the 850 (27 percent), the 124-1430 (24 percent), and, the future blockbuster, the 127 (12 percent), which launched in 1972.

ENASA, MI, and the former Elizalde also prospered starting from the end of the 1950s. The first of these companies produced Pegaso heavy trucks, although its most modern plant was built in Madrid. The second one built Ebro brand light trucks first under license from Ford and from 1965 under a patent from Massey Ferguson, which acquired 32 percent of the company’s capital.Footnote 83 For its part, Elizalde, reconverted into Empresa Nacional de Motores de Aviación SA (ENMASA), reached an agreement with Daimler Benz AG to produce diesel engines and Mercedes-Benz vans, even developing an engine for SEAT. In 1969, it became Compañía Hispano Alemana de Productos Mercedes-Benz Sociedad Anónima (CISPALSA), Mercedes-Benz being its main shareholder and the INI remaining in a minority position. In the mid-1970s, reconverted into Compañía Hispano Alemana de Productos Mercedes-Benz (CHAM Benz), it produced around ten thousand vehicles a year, output similar to that of ENASA and MI. Footnote 84

Until the mid-1970s, Spanish industrial policy maintained strict quotas on automobile imports, strong domestic production requirements for the manufacturers installed, and a restrictive policy of authorizations.Footnote 85 When it relaxed the rules on foreign capital (increasing it to a maximum of 49 percent of the share capital), the general trend was toward the creation of companies in which European component manufacturers had a stake as minority shareholders.Footnote 86 The market was the main form of coordination between the auxiliary industry and the end manufacturers, among which SEAT stood out. The policy of the public constructor was to have two suppliers per product, and it rarely tended to have a stake in the capital of its suppliers. Indeed, the internal control of the suppliers by holding a stake in their capital was more frequent for the suppliers located far from the district, such as Purolator Ibérica (Madrid) and Victorio Luzuriaga (Basque country). Likewise, when the production of certain components was shown to be problematic, an attempt was made to introduce suppliers of Fiat. This was the case for ball bearings, produced from 1951 by the Empresa Nacional de Rodamientos, a subsidiary of the INI established in Madrid in 1947, which operated with licenses from the Swedish firm SKF. The continuous production deficiencies in Madrid meant that, in 1956, SEAT fostered the establishment in Barcelona of a subsidiary of the Italian firm RIV, a supplier of Fiat in Turin.Footnote 87

The 1958 industrial census showed that, in the Barcelona district, 15,823 people were employed in the production of road vehicles, of whom 5,559, one-third, were employed by SEAT. The consolidation of domestic production enabled the district to attract foreign technology and capital, which came from companies such as Pianelli, Traversa, and Bendix. In the mid-1960s, some of the companies that stood out were Harry Walker (carburetors), Deslite (bearings), Auto Electricidad (fuel pumps), Fundiciones Industriales (liner and piston rings), Faros Españoles (headlights), Artés de Arcos (dashboards), Gallital Ibérica (water pumps), Skreibson (radios), Eaton Livia (valves for engines), Pirelli (tires), and the various subsidiaries of Pujol y Tarragó, which would become Ficosa, one of the district’s most dynamic companies.

The origins of Ficosa go back to 1947, when Josep M. Pujol, still an adolescent, left school to become an apprentice in Talleres Motor, an establishment devoted to repairing carburetors and manufacturing control cables. There he became close friends with a mechanic, Josep M. Tarragó, who would become his future partner and brother-in-law. In 1949, after Pujol had spent some months in the workshops of the Barcelona section of Mercedes-Benz, they jointly established the company Pujol y Tarragó S.L., a small workshop devoted to manufacturing cables for brakes, accelerators, and clutches, located in the Barcelona neighborhood El Clot. The company supplied cables to Biscuter, Eucort, Pegaso, and Industrias del Motor Sociedad Anónima before becoming a supplier of SEAT, first indirectly, providing cables for the control panels manufactured by Bresel, and later as a direct supplier. At the end of the 1950s, Pujol y Tarragó began a strategy of diversification that involved creating small independent companies highly specialized in very specific products. Industrias Technomatic (windows and sun visors) and Transpar Ibérica (windshield wipers and rearview mirrors) both opened before the 1960s. In the second half of the decade, it founded Cables Gandía SA (steel transmitters), Techno Chemie (rigid pipes), and Lames Ibérica (plastic materials). These were all small units controlled by a supervisor; when they gained a certain size, they were managed by an executive. In 1974, Pujol y Tarragó created the Compañía Holding Serco, which became Ficosa in 1976, conceived as a means of coordinating the network of industrial companies that operated as divisions and whose managers enjoyed a wide margin of autonomy. The first of the subsidiaries established abroad, a workshop devoted to producing control cables located on the outskirts of Porto, in Portugal, opened in 1971.Footnote 88

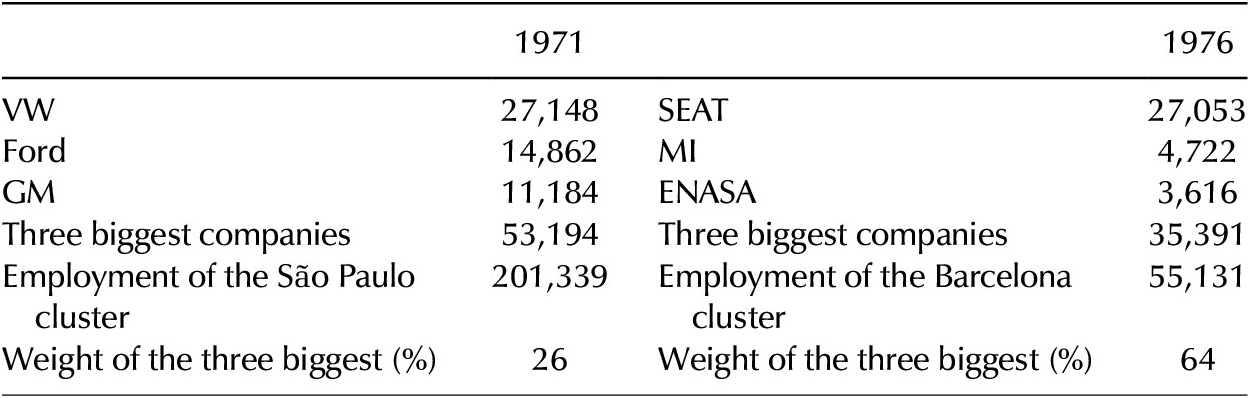

Between 1936 and 1960, the number of people employed by the automobile industry of Barcelona increased more than threefold to around twenty thousand people in 1962. Madrid and the Basque country, the next-largest Iberian regions in terms of numbers of employees, had less than ten thousand employees each.Footnote 89 In the mid-1970s, the automotive district of Barcelona employed some fifty-five thousand workers (Table 3).

Table 3 Employment generated by the leading companies and total employment of the automobile cluster of Barcelona

Source: Catalan, “The Life-Cycle of the Barcelona Automobile-Industry Cluster, 1889–2015,” 77–124.

Barcelona confirmed its leadership of the main automobile industry cluster in Spain, despite the fact that its institutions were weakened as a result of the establishment of the Franco regime. The INI’s centralizing policy forced SEAT, ENASA, and ENMASA to have their head offices in Madrid. MI, under private control, was the only company with more than one thousand workers that maintained its headquarters in Barcelona. Furthermore, the Automobile Fair of Barcelona could not reopen until 1966, more than three decades after it was last held in 1935. Right from the beginning, the big companies in this sector internalized material training by creating technical schools, developing engineering departments, and promoting training courses. ENASA inherited the apprenticeship school of Hispano-Suiza and developed its facilities in Barcelona as an engineering center.Footnote 90 Elizalde (then CISPALSA/Mercedes-Benz) had an apprenticeship school from 1927.Footnote 91 SEAT inaugurated its school in Zona Franca in 1957, and at the beginning of the 1970s, built its Martorell Technical Centre, which became one of the main R&D centers of the Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 92 For its part, MI decided to locate its engineering department in its new Zona Franca facilities, which opened in 1968.Footnote 93 This set of internalized activities tended to replace the task formerly undertaken by local institutions, such as the Escuela Industrial and the Escuela del Trabajo. It is true that these organizations, like the rest of the educational institutions and those promoting industrial activity that were created or revitalized both by the Mancomunitat of Catalonia (established in 1914 and disbanded with the dictatorship of General Primo de Rivera in 1923) and by the Generalitat of Catalonia (restored in 1931 and abolished in 1939 with General Franco’s dictatorship) were decidedly weakened during the Franco regime. However, although the institutional development of the cluster was less satisfactory than before the Civil War, the Marshallian externalities that hundreds of companies and thousands of workers could provide were reinforced.

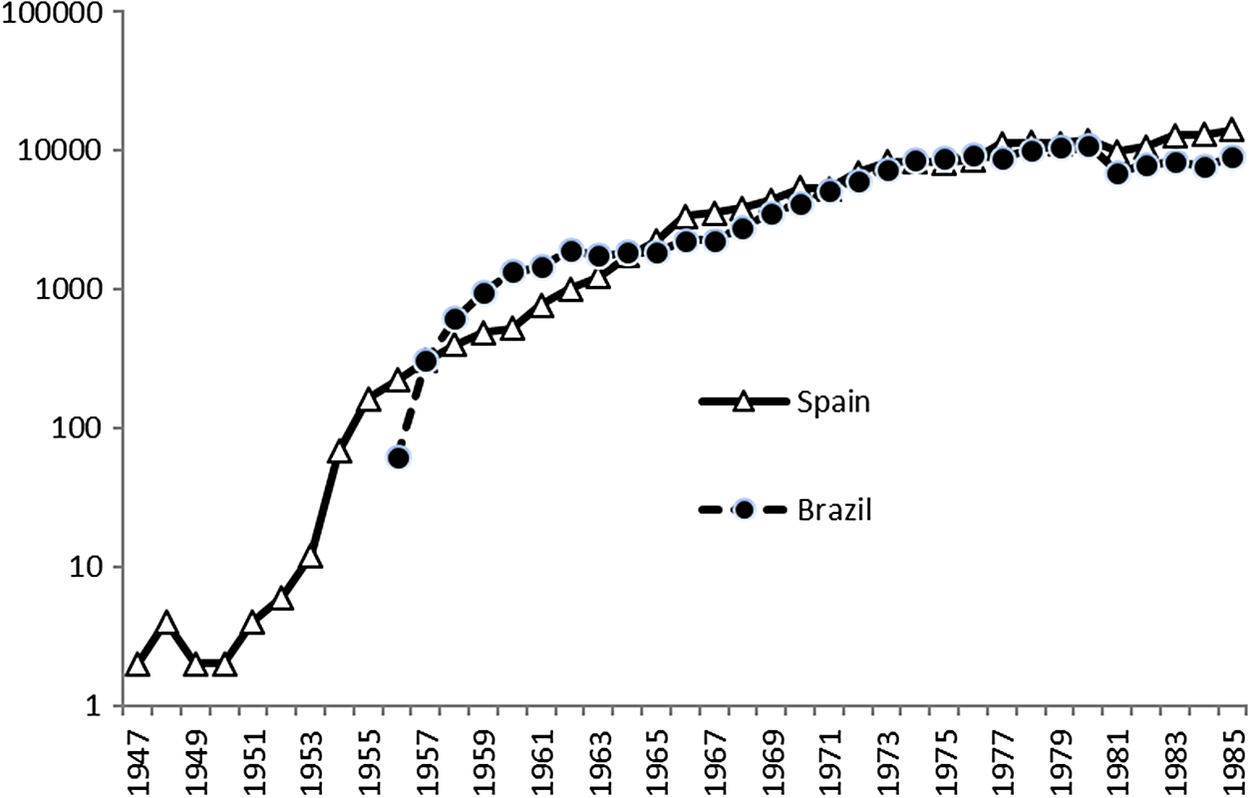

In the mid-1970s, Barcelona Province had around three hundred plants that made automobile parts or assembled them. The cluster was highly hierarchized around its main companies, the biggest generating somewhat more than 60 percent of the total employment (Table 3). However, the rapid expansion recorded by the cluster is mainly explained by the emergence of SEAT, created with a weak link to the institutions of the district. SEAT, which in 1976 directly generated almost half of the district’s employment (Table 3) and whose large demand for consumables sustained the majority of the cluster’s companies, took off thanks to the protectionist policies. Therefore, the results obtained tend to confirm the hypothesis of Chang and of the rest of the authors who insist on the need for industrial policies in developing countries. As discussed later, the São Paulo cluster experienced a similar evolution, although with some nuances (Fig. 1).

In Brazil, Getúlio Vargas tried to promote truck construction in the Fábrica Nacional de Motores (FNM). This publicly owned company was originally created with the financial support of the United States to build aviation engines under license from the Wright Company, during World War II in Rio de Janeiro. When the factory was finally established, the conflict was already over, and it ended up being reconverted to build trucks under license from Isotta-Fraschini.Footnote 94 The planned program was to build around two hundred trucks a year, using a minimum of 30 percent of components of domestic origin. However, shortly after launching the first vehicles, it had to change its technological partner, given that the Milanese firm was forced to abandon automobile construction. During the 1950s, it continued to build trucks with another partner from Lombardy, Alfa Romeo. However, like ENASA in Madrid, the FNM in Rio never succeeded in becoming a very competitive company. Nevertheless, Vargas opposed its privatization during his last government as democratic president (1951–1954).

Meanwhile, in the capital of São Paulo, 122 component manufacturers joined forces at the end of the decade to support market protection. They created the Associação Profissional das Industrias de Peças para Automoveis e Similares de São Paulo (later Sindieças).Footnote 95 Its demands were well received by the government of Vargas, which came to power following the presidential election by direct vote in January 1951. In 1952, the Associação presented a report that highlighted the existence of 250 companies capable of manufacturing 162 groups of automotive parts and components. Six months later, Vargas issued Notice No. 288, which introduced a veto on importing 104 groups of parts and components. With Notice 311 of April 1953, Vargas also banned the importing of complete vehicles, only authorizing the entry of CKD kits if they arrived without the parts specified in Notice 288.Footnote 96 Before the end of the year, Willys-Overland and Volkswagen (VW) had established assembly lines in São Paulo, while Mercedes-Benz installed its line in Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 97 However, as occurred with Ford and GM, these facilities were far from being true automobile factories.

Following the suicide of Vargas in August 1954, João Café Filho’s new government reversed some of the measures taken, but maintained very low levels of vehicle imports.Footnote 98 When Juscelino Kubitschek (JK) won the October 1955 presidential election, Ford was producing 10 trucks a day despite having the capacity for 125. General Motors do Brasil, which could assemble some two hundred vehicles a day, was hardly building five.Footnote 99

Figure 1 The take-off of automobile production in Brazil and Spain (hundreds of units manufactured).

On February 1, 1956, shortly after taking office, JK promoted a National Development Plan (known as Plano de Metas), which established 31 goals distributed in five major groups (energy, transport, food, capital goods, and education), in addition to the construction of a new capital in Brasilia.Footnote 100 Automobiles were the only consumer goods indicated as a strategic objective. To ensure their production, the Executive Group of the Automobile Industry (GEIA) was established in June 1956. Its objective was to achieve the production of 170,000 vehicles in 1960 (80,000 trucks and buses, 50,000 four-wheel-drive and light commercial vehicles, and 40,000 passenger cars). Moreover, manufacturers had to incorporate 90 percent of local content for trucks and light commercial vehicles, and 95 percent for cars and four-wheel drive vehicles. The GEIA enjoyed absolute discretion in relation to the companies of the sector, being able to grant privileged exchange rates and credit. As in Spain, the automobile market was closed to foreign production, but the licensing policy was more lenient and favorable to foreign investment.Footnote 101

Kubitschek’s government considered the automotive sector to be strategic, and direct foreign investment was a preferential channel for accessing the technology and the capital required to promote it.Footnote 102 The GEIA approved eighteen projects for the final construction of vehicles, of which eleven were viable.Footnote 103 The great majority of these brands were already established in Brazil, but until then had limited their activity to assembly, using low percentages of components of local origin. Starting in 1956, high degrees of nationalization were required in order to be able to continue manufacturing in the country. From a comparative viewpoint, it can be considered that authorizing around twenty brands was risky, too many brands to be able to take full advantage of the returns to scale characteristic of the industry.Footnote 104 However, irrespective of their final viability, it is worth underlining here that almost all the major worldwide manufacturers chose São Paulo and its surrounding area to locate new factories or expand existing ones. This was the case for Ford, GM, International Harvester, Scania, Toyota, Vemag, VW, and Willys-Overland. It is important to note that, in order to accomplish the new and more ambitious goals, Mercedes-Benz quickly moved its factory from Rua Bela in the city of Rio de Janeiro to São Bernardo do Campo.Footnote 105 The only important exception was the already mentioned Fábrica Nacional de Motores, which assembled trucks at a rate of two hundred units a month.Footnote 106 Simca was the only company that initially planned to operate on a large scale outside São Paulo, specifically in Belo Horizonte, the capital of Minas Gerais. Later, however, it also ended up choosing the São Paulo district.

Between his election victory and his investiture, JK traveled to the United States and Europe to present his developmental program. While in France, Kubitschek visited the Simca factory and was enthralled by the facilities. The future president encouraged the French to establish a factory in Brazil, preferably in his native Minas Gerais. Simca do Brasil, in which the French had a minority stake, was founded in Belo Horizonte in May 1958, on industrial land provided by the governor of the state. However, when it began to operate in March 1959, it did so from a rented workshop located in São Bernardo do Campo, 800 kilometers away. The decision was taken by the second technical authority of Simca, who was in Brazil monitoring the operation. One year later, the Brazilian subsidiary admitted that its transfer to Belo Horizonte was unfeasible, as practically all of its almost one thousand suppliers were located in São Paulo, including Ford, which supplied the engines.Footnote 107

VW (São Bernardo do Campo), Willys-Overland (São José dos Campos and Taubaté), and Mercedes-Benz (São Bernardo do Campo) built modern new factories for the complete manufacture of automobiles. In particular, Kubitschek’s insistence helped VW to complete the plan to manufacture its Combi, together with that of its star product and mass-produced car, the Beetle (Fusca in Brazil).Footnote 108 As occurred in Barcelona with the 600 model, for the cluster to expand it was essential to be able to have a cheap car for a relatively poor country. Also, like the 600, in a very short time, 95 percent of the VW Fusca’s components were manufactured in Brazil.Footnote 109

Ford and GM, much more reluctant to intensify production in Brazil, were likewise forced to change their attitude.Footnote 110 In March 1959, GM inaugurated a comprehensive Chevrolet engine factory in São José.Footnote 111 For its part, Ford built an engine-stamping plant in the Ipiranga neighborhood, next to the assembly factory it had inaugurated in 1953, installing the casting in the adjacent municipality of Osasco.Footnote 112

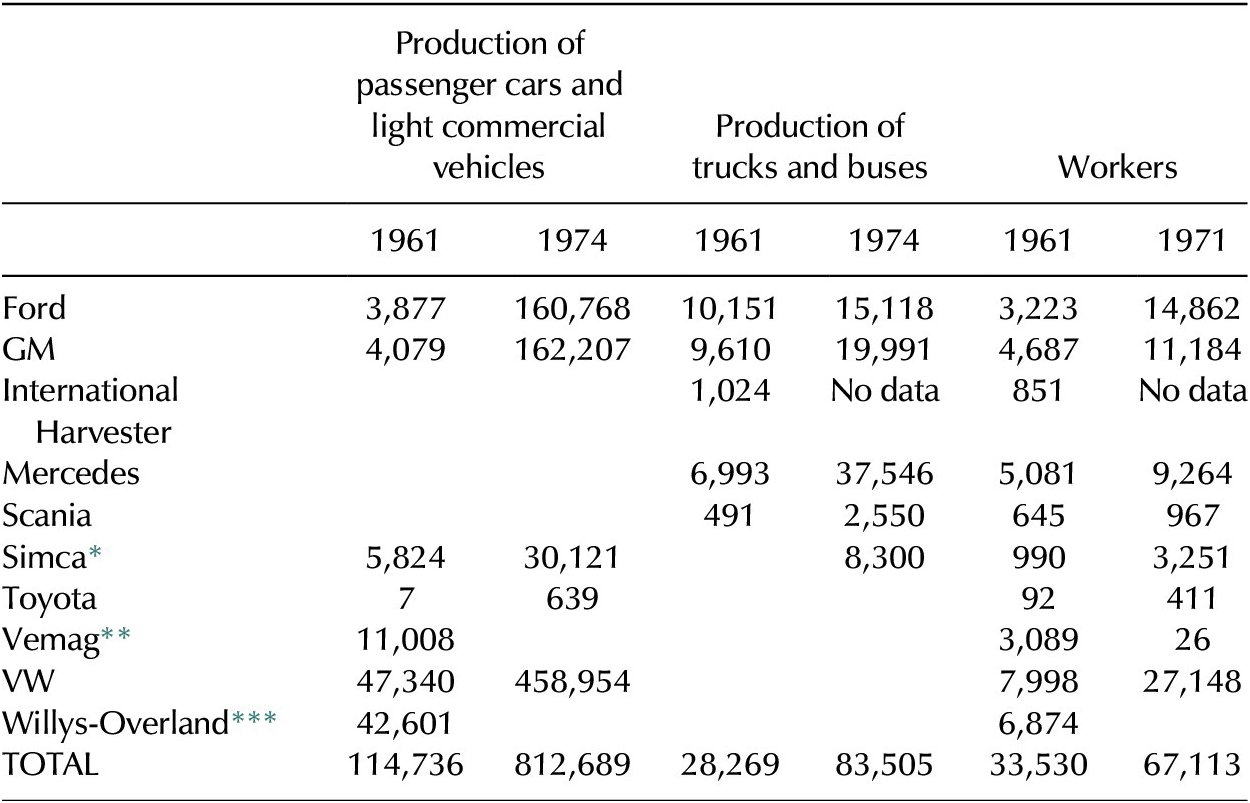

The industrial policy promoted through the Plano de Metas favored the final take-off of the São Paulo district. In 1961, the cluster’s production was close to 150,000 vehicles (Table 4) that, moreover, included domestic content percentages above 90 percent, fully manufactured in the district.Footnote 113 Despite this, Kubitschek’s government had to contend with the direct opposition of international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, with which it broke off relations in 1959.Footnote 114 The cluster had embarked on a path of development from which it would not deviate, even with the severe crisis that broke out in 1962 or with the 1964 coup d’état.

Table 4 Production and employment in the São Paulo cluster: production (units) and workforce (number of employees) by manufacturer

Source: Authors’ elaboration from Anfavea, Indústria Automobilística Brasileira.

* Chrysler from 1967.

** Acquired by VW in 1965 and closed in 1967.

*** Acquired by Ford in 1967.

The military coup, initially led by Humberto Castelo Branco, did not change the automobile policy, although they moderated the expansionist stimulus of the democratic governments. Automobile production in Brazil, which had gone from fewer than 10,000 vehicles in 1956 to more than 150,000 in 1964, exceeded half a million vehicles in 1971. By the middle of the decade, it reached around eight hundred thousand units.

The evolution of the number of employees in the São Paulo cluster corroborates the development experienced by the Brazilian automotive industry. In 1971, the 67,113 workers employed directly by the end manufacturers were more than double those of 1961 (Table 4). The ratio between the producers of parts and end manufacturers established in São Paulo was around 2 to 1, and it can therefore be estimated that, in 1971, the cluster gave employment to around 201,339 workers.Footnote 115

Brazilian production continued to expand rapidly in the early 1970s. Almost the entire automobile industry of the federation was concentrated in the São Paulo region, and by 1974 the cluster exceeded one hundred thousand direct jobs with manufacturers and was close to two hundred thousand with suppliers. Consequently, the size of the São Paulo cluster was significantly larger than that of the Catalan district.

As the cluster finally took off, it clearly fit in with Markusen’s category of a hub-and-spoke district. If we accept the figure of 201,339 workers employed in the cluster in 1971, just three big companies (VW, GM, and Ford) already employed 53,194 workers. This would mean that the three leading firms concentrated 26 percent of the employment generated by the São Paulo automotive cluster. Although the relative weight of the three leading corporations in the São Paulo cluster was not as overwhelming as in Barcelona, the significant proportion suggests that the big companies of the industry provided the district with crucial capabilities for its final take-off (Table 5). We should, moreover, take into account that during the 1960s, the big foreign companies increased their degree of control of the suppliers located in the São Paulo cluster.Footnote 116.

Table 5 Employment generated by the leading companies and total employment of the São Paulo and Barcelona clusters

Sources: Authors’ estimation from Anfavea, Indústria Automobilística Brasileira; and Catalan, “The Life-Cycle of the Barcelona Automobile-Industry Cluster, 1889–2015,” 77–124.

Following the 1956 decrees, the car manufacturers sought to attract their international suppliers and, when this was not possible, they assigned manufacturing licenses to local employers. However, when the costs of controlling the local suppliers were too high, they chose to internalize production, which was in turn a sign for the rest of the companies from the district. As the development of the sector intensified in the 1960s, the trend was for local companies to be acquired by the big transnationals, which preferred this to opening new companies.Footnote 117 One of the sectors that evolved the most was the production of cast and forged products and the steel industry in general, spreading the benefits of its technological and organizational modernization to the overall industrial fabric of São Paulo. At the beginning of the 1970s, this allowed most of the machines used in the automobile industry to be manufactured within the cluster, even the most complex, such as those that operated the engine head.Footnote 118

The district was apparently coordinated by the market, in which the end constructors could impose their conditions, although the trend was to increase control over the companies of the auxiliary industries. In its early years, the action of the GEIA, which had the power to temporarily suspend import licenses, was biased toward the interests of the local automotive parts manufacturers. When the end constructors rejected the local parts, alleging a lack of quality, the GEIA commissioned external appraisals, often from the São José Technological Institute, thus disciplining the big transnational companies. Taking advantage of its arbitration function, the GEIA fostered dozens of cooperation agreements between automotive parts manufacturers and constructors to encourage the transfer of technical and organizational knowledge, although it did not hesitate to foster joint ventures with international suppliers when the complexity of the production was beyond the reach of local producers.Footnote 119

From the early 1950s, the developmental dynamics of the cluster was characterized by a combination of local initiatives, together with the establishment of subsidiaries of big international groups. Sofunge, a company controlled by local capital and chaired by Eduardo Simonsen, the son of the São Paulo industrialist leader Roberto Simonsen, cast engine blocks and manufactured engine heads even before the approval of the 1956 decrees. Its products also incorporated aluminum pistons forged by companies from the district, such as Roberto Klopel & Filho, Regemotor, and Lugino Grandes, which, following the JK decrees, were joined by another two new companies, Metal Leve and Cofap. On the other hand, the manufacture of the first gearboxes required the installation of a subsidiary of the German ZF, while the large-scale production of forged parts experienced a huge boost with the establishment of Sifco, a subsidiary of the American Steel Improvements. Other historical companies from the district, such as Albarus, which sold transmission parts to Ford from 1949, and Filtros Mann, which produced oil filters, ended up being controlled by Dana Corporation and Tilterwerke Mann, respectively. Another example is Amortex, which supplied bumpers to VW and Mercedes-Benz and ended up being taken over by the German Sacks GmbH in 1961. In the mid-1960s, Willys-Overland took over Bongotti, a radiator manufacturer, while VW purchased Forchedo, an important smelting plant. However, the most important acquisition took place when Mercedes-Benz took over Sofunge, probably the strongest automotive parts company of the district under local control.Footnote 120

In the mid-1960s, the restrictive macroeconomic policy applied to control unbridled inflation hit the local manufacturers who lacked access to the international capital markets particularly hard. The economic turmoil was taken advantage of by the big transnational companies, both end manufacturers and automotive part producers, to strengthen their control over the district’s companies.Footnote 121 In this process, the subsidiaries of the end manufacturers hierarchized the cluster, simultaneously disseminating a large part of their technological and organizational capacities.

Although the local institutions continued to undertake important work, the weight of the small and medium-sized companies under local control gradually decreased. In the 1960s, the manufacturers’ associations worked to improve the capacities of the vehicle parts companies, offering their members technical assistance, mainly through the Technological Institute of Aeronautics in São José dos Campos.Footnote 122 They also coordinated with the region’s higher education institutions to offer courses in metalworking, mechanics, and electricity, as well as degrees and postgraduate courses in engineering, economics, and business administration. Although their actions helped to promote the cluster, as occurred in Barcelona, the strategic industrial policies were the decisive factor for its take-off. Once the policies that promoted the development of the automobile industry were applied, they reinforced the concentration of companies in São Paulo, enabling the industry to reap the competitive advantage generated by the abundance of skilled workers and specialized suppliers. The international companies that best adapted to the incentives established by the industrial policy ended up dominating the cluster and contributing decisive capabilities to strengthen their competitive advantage.

Conclusions

The Barcelona and São Paulo clusters originally emerged as a result of the presence of Marshallian-type external economies. Before the Great Depression, both districts were the most industrialized regions of agricultural-based developing countries. They had many mechanical engineering workshops and factories and an abundant workforce used to industrial discipline. They also accumulated specific knowledge of the industry, thanks to the establishment of constructors or assemblers such as Hispano-Suiza, Elizalde, and Ford MI in Barcelona, and Grassi, Ford, and GM in São Paulo. During the interwar period, small workshops focused on the spare parts market proliferated in both districts. In both cases, during the formative period of the cluster, the industry had the support of its own local institutions. Nevertheless, neither Barcelona nor São Paulo crossed the threshold of mass production before 1950.

The take-off of both clusters began in the 1950s, thanks to the adoption of a strategic industrial policy. This included protected markets, different types of subsidies, the obligation to include high percentages of domestic content, and a commitment to popular vehicles well adapted to the local market potential. The manufacturers that accepted these conditions provided production, management, and distribution and marketing capabilities to both districts, and the districts ended up becoming true cluster nodes. Although these policies were applied nationally, the bulk of their impact was captured by regions with a previous base in the art. In Barcelona, the prominent player was basically SEAT (FIAT holding a minority stake), although the contributions of MI (formerly Ford) and ENASA (formerly Hispano-Suiza) were also important. In São Paulo, the predominant role was played by VW, followed by Ford and GM, which ceased to be assemblers and became manufacturers.

These companies introduced mass production in both districts and thus permitted their expansion. The local business fabric was able to take advantage of the high percentages of national production required by the administration, although both clusters also experienced the arrival of foreign suppliers. To ensure the success of their international operations, the big end manufacturers transferred their organizational capacities to the companies of the district. Thus, the large mass production companies, at the same time as strengthening the cluster’s competitive advantage, structured it in accordance with their interests. Barcelona’s 600 and São Paulo’s Fusca, true people’s cars, triumphed thanks to their low cost and their features and were manufactured with greater than 95 percent of national components. Both clusters evolved, adopting a very hierarchized structure around a few end constructors. To summarize, they were districts that conform well to the concept of hierarchical clusters.

Without a strategic industrial policy, the clusters in question would not have achieved the same level of development and would certainly have maintained their character as mainly importers or assemblers. The strategic policy succeeded in encouraging big local companies or subsidiaries of multinationals that dominated the industry to contribute their technological, organizational, and distribution and marketing capabilities to the development of the district, having a crucial impact on their take-off. The local institutions did not make a comparable contribution.