1. Introduction

The contemporary expansion of English is becoming remarkably rapid and exceptionally global (Ostler, Reference Ostler2011). In present-day China, English has gained unprecedented popularity, fueled by the nation's current political and social development (Bolton & Graddol, Reference Bolton and Graddol2012). There is a notable trend of bilingual education using English as a medium of instruction in Chinese schools (Wei, Reference Wei2013). Therefore, an increasing number of Chinese are enthusiastic about learning and using English in communication. With the active participation of youths, ‘Internet English’ has been used widely in social networking spaces. The practice of ‘English mixing’ in various Chinese homegrown social networking sites has become the most remarkable intranational use of English in today's mainland China (Zhang, Reference Zhang2012). Interestingly, youngstersFootnote 1 often create novel meanings when using languages on the Internet as ‘teenagers are well-known for introducing innovations into language, and indeed are generally regarded as prime agents of language change’ (Palacios Martínez, Reference Palacios Martínez and Ziegler2018: 363). Many linguistic studies have dealt with the mechanisms of the evolution of word meanings in past decades (Kachru, Reference Kachru1983; Qin & Guo, Reference Qin and Guo2020; Tan, Reference Tan2009; Yang, Reference Yang2005). Much evidence indicates that meanings and usages of words are variable and composite, and may turn out differently depending on how words are used in contexts.

‘Emo’, as an English lexical expression, appeared 60,441 times between August 16 to August 22, 2021, according to the Baidu Index (a valuable tool to track online information-seeking behaviors of Internet users in China). Since November, topics regarding ‘emo’ have already been viewed more than 200 million times on a single social media platform, Sina Weibo (one of China's biggest social media platforms). ‘Emo’ has been exploding in popularity online and has been given many new localized meanings and usages as an Internet buzzword since the second half of 2021 in many Chinese social media. While this buzzword is typically understood to be the colloquial language by youngsters, people from other social groups or backgrounds may not develop an accurate understanding of its usages and meanings. For example, Zhang Jie, an influential pop star in China with 81.533 million Sina Weibo followers, has put forward a question on his Sina Weibo: ‘What is emo? I have grown up as an adult. These emerging languages, please be nice to me, ok? (Inserting a meme showing his look of shock)’.Footnote 2

In the above post, although Zhang Jie is Chinese, however, as a middle-aged adult, he showed his incomprehension but interest in this new Internet buzzword that Chinese youngsters created. Therefore, this study primarily aims to outline a comprehensive understanding of this new lexical unit for those, just like Zhang Jie, who are puzzled yet interested in it.Footnote 3 To address this purpose, this study investigated the emerging Internet English neologism ‘emo’ used by university youngsters on a popular Chinese social media platform, i.e., WeChat. Besides, examinations of the English lexical innovations in Chinese social media settings remain scant. By doing this study, it was hoped to obtain a better understanding of Chinese English's lexical nativization and linguistic innovation concerning the web-communicated context.

2. Innovations in the lexis

The definition of innovations in the lexis, commonly lexical innovations or neologisms, varies depending on distinct research directions that different linguists focus on. Still, it is widely assumed that the lexical innovation describes a lexical form implying novelty of some sort (Buckingham, Reference Buckingham and Brown1981). In this study, it is defined as a newly coined word unfamiliar to most speech community members (Kerremans, Stegmayr & Schmid, Reference Kerremans, Stegmayr, Schmid, Allan and Robinson2011). Previous studies have increased transparency in the processes by which new words are created (Miller, Reference Miller2014), and the processes by which word meanings evolve over time (Geeraerts, Reference Geeraerts2010). Efforts have also focused on how words become lexicalized as they gradually undergo changes of forms and meanings, and how words become implemented as they enter a language's standard lexicon (Brinton & Traugott, Reference Brinton and Traugott2005).

Recent studies on lexicology show that English words might be innovatively altered on different linguistic perspectives. Unique phonetic properties, such as tonal structures and playful sounds, may be created to render desired communicative effects (Oladipupo & Unuabonah, Reference Oladipupo and Unuabonah2020; Pavlova & Guralnik, Reference Pavlova, Guralnik and Pavlova2020). Neological anglicisms also show remarkable features of spellings, or morphological processes such as affixation, either maintaining their original English forms without any modification or being adapted anglicisms (Rodríguez Arrizabalaga, Reference Rodríguez Arrizabalaga2021). For instance, Munday (Reference Munday, Anderman and Rogers2015: 62) uses ‘cyberspanglish’ to refer to lexical units combining an anglicism with a native Spanish element (e.g., affix, base). Sometimes, Internet users mix the invented English words with their first language to form blend genres and styles in communication. The code-mixed English lexes might follow particular syntactical rules of the creators’ first language or English grammar (Zhang, Reference Zhang2012; Zhang, Reference Zhang2015). Some English or anglicised expressions also function as discourse-pragmatic markers collocating with new functions in different contexts. For instance, ‘aunty’ in Malaysia (Lee & Shanmuganathan, Reference Lee and Shanmuganathan2020), ‘now’ and ‘mehn’ in Nigeria (Oladipupo & Unuabonah, Reference Oladipupo and Unuabonah2020; Unuabonah, Reference Unuabonah2022). Having said all of the above, neologisms, specially produced in the web world, exhibit particular linguistic features and functions, making up a mixed language modality that combines various elements of communication practices embodied in conversation or writing (Baym, Reference Baym2010).

With the advent of the Internet and computer-mediated communication, speech systems are increasingly adapted to compensate for users’ inherent inadequacies or specific intentions. The Internet serves as a public platform for everyone to freely express themselves, regardless of racial and educational background. Varied creative usages of languages with emerging Internet resources have resulted in a burst of neologisation in today's world Englishes (Lu & Wei, Reference Lu and Wei2018; Martseva et al., Reference Martseva, Snisar, Kobenko, Girfanova, Filchenko and Anikina2017). Neologisms or innovative lexes are an essential part of the network culture of the speech community and can be accurate representations of people's real-life activities (Liu, Reference Liu2018).

The present-day academic foci are more centered on Internet language innovations or linguistic creativity among young generations. Some terms are created to refer to the specific language used by youngsters in web-mediated communications, such as ‘netspeak’ (Crystal, Reference Crystal2006) and ‘virtual language’ (Pop, Reference Pop2008). Due to the close interrelationship between young generations and the Internet, it is no surprise that social networks have become a highly productive resource for lexical innovations and linguistic creativity in English (Rodríguez Arrizabalaga, Reference Rodríguez Arrizabalaga2021). More recently, those neologisms used in social networking spaces occupy a privileged position because they are currently, as Vettorel (Reference Vettorel2014: 6) asserts, ‘the preferred means to keep in touch with friends.’ Because of the very common presence of English in Chinese social networking spaces, we agree with the statement that ‘in the virtual world, English exerts more of its influence among its speakers as seen in social media and chat avenues’ (Reyes & Jubilado, Reference Reyes and Jubilado2012: 43). Social media have become increasingly significant web resources for lexical innovations featuring informality and creativity (Würschinger, Reference Würschinger2021), which provokes them as important platforms for investigating lexical innovations.

3. ‘Emo’ in bilingual China

‘Emo’ may seem not unfamiliar to those speaking English as a native language or possessing advanced English proficiency. This term was initially used in the 1990s to deal with a specific combination of punk and indie rock, with lyrics concentrating on scorned love, loneliness and depression (LaGorce, Reference LaGorce2005; Ryalls, Reference Ryalls2013). Emo-themed mass media, such as newspapers, magazines and websites, have explained that ‘emo music artists and their devoted listeners display distinct fashion styles: wearing predominantly dark-colored clothing, heavy eyeliner, tight trousers and dyed hair quaffed to cover one eye’ (Chernoff & Widdicombe, Reference Chernoff and Widdicombe2015: 305). Earlier empirical works on emo also associate it with psychological dysfunction related to suicide, depression and self-harming behaviors (Scott & Chur–Hansen, Reference Scott and Chur–Hansen2008; Sternudd, Reference Sternudd2012; Young, Sweeting & West, Reference Young, Sweeting and West2006). Even though being a legitimate English lexicon, emo has been known as a music genre and connected with clinical-perspective research, and thus is less widely applied in speakers’ everyday interactions.

In today's bilingual China, it has recently taken on new meanings and wider usages on social media platforms (see Figure 1). According to a report published on September 18, 2021 (Wang, Reference Wang2021), ‘emo’, in the modern Internet context, is more frequently used as an abbreviation for ‘emotional’, and is used by lots of Chinese to refer to a complex emotional status or moodiness that pops up in their everyday life. Its semantic meaning becomes exceptionally vague, and there are no limits to what it describes. According to Baidu Encyclopedia, ‘emo’ is used on web discourses to convey a negative sentiment, e.g., grief, sorrow, sadness, melancholy. The ‘emo’ phenomenon on social media relies on pop culture among young generations and the bilingual creativity of Chinese English. Generally, ‘emo’, as a popular Internet English buzzword, has been rendered with new meanings in the Chinese context. For instance, the Chinese-English mixing clause ‘我很 emo’ (wǒ hěn emo: I am very emo) describes the self as possibly ‘I am emotionally unstable’, ‘I am unhappy’, ‘I am foolish’, etc. Despite the high usage intensity among many bilingual speakers in China, there is no systematic literature on explicating ‘emo’. This study, therefore, aims to examine some general knowledge pertinent to the formation, features and usages of this innovative lexical item.

Figure 1. Instances of ‘emo’ from a video-sharing website, WeChat moments, and WeChat group chat

4. Methodology

The data were collected from naturalistic conversations offered by 35 female undergraduate students at a mainland Chinese university. All participants are frequent WeChat users. The rationale for using WeChat as the data resource is that it is one of the most popular and active chatting social media platforms in China, especially among China's young generations (Zeng Skovhøj, Reference Zeng Skovhøj2021). The participants searched for the keyword ‘emo’ in their WeChat chat logs, then they screen-captured textual conversations involving ‘emo’ by drawing on the principle of voluntariness.

Prior to the transfer of screenshots, identifying information has been removed for anonymity and privacy. Each conversation must display a complete context to ensure the understandability of the communicative intention and implied meaning. The analysis focused on the representation of ‘emo’ in light of linguistic features and discourse-pragmatic functions to establish a comprehensive understanding of it. 399 WeChat conversations, encompassing 507 occurrences of ‘emo’, were collected as the corpus. Observations and questions were also used to gather necessary data concerning ‘emo’ pronunciations and morphological formations from 15 participants. The two authors transcribed and analyzed the collected data independently and then compared their coding until they agreed on the results of the coding and analysis. This process of securing inter-rater reliability assists in achieving reliability for the study.

5. Results

5.1 Linguistic features of ‘emo’

The main focus of this study is ‘emo’ which is defined as an Internet neologism in contemporary Chinese English. This section presents the findings concerning phonetic properties and grammatical properties including morphological traits and syntactic analysis of ‘emo’, respectively.

5.1.1 Phonetic properties

Though this study primarily intends to be a discoursal investigation, a phonetic observation is necessary. Findings present participants’ (n = 15) distinct pronunciations of ‘emo’. It is mostly pronounced as [ˈiːməʊ] (n = 12/80%), which is the same phonetic structure as the existing lexis ‘emo’ that is a rock music genre. Other pronunciations are also observed, though with a minimal occurrence, and are presented by the International Phonetic Alphabet as: [ˈeːməʊ] (n = 1), [iːˈməʊ] (n = 1), or directly read by letters ‘e’ ‘m’ ‘o’ (n = 1).Footnote 4 All of them are not the same as the pronunciations of emotional [ɪˈməʊʃənl] and emotion [ɪˈməʊʃn] that are generally perceived to be the origin of ‘emo’. The differences are found in the first vowel and stress of the phonetic structures. Speakers might not be familiar with the widely accepted pronunciation of ‘emo’ because of its new emergence. In addition, these distinctive phonetic patterns may be caused by youngsters’ behavioral preferences to add a tone of informality to their speech. This finding suggests that although lexical units are identical in spelling, youngsters’ cognitive resources in sound recognitions may vary. When faced with lexical innovations even of simple syllable distinctions, young Chinese people potentially start anew with phonetic creations, which may alter representations of different phonemes. Figure 2 illustrates how ‘emo’ is commonly presented with its tonal structure and pitch contours in a representative daily communication by Chinese youngsters.

Figure 2. The pitch contour of emo as rendered in the utterance ‘我emo了 (I emo[+ed/past tense])’

5.1.2 Morphological formation

Young people prefer to reduce or shorten common words in everyday communication for convenience, efficiency, familiarity and intimate relationships (Casado Valverde, Reference Casado Valverde2015). In English, we often find cos instead of because, uni for university (Palacios Martínez, Reference Palacios Martínez and Ziegler2018). Similarly, the abbreviation is generally claimed as the morphological formation of ‘emo’ (Shi, Reference Shi2021). Abbreviation involves shortening a word, encompassing three main methods: clipping, acronyms and blends. Clipping is frequently used in modern English morphological formations, which shorten or ‘clip’ one or more syllables from a word, e.g., ad and advertisement. In general, ‘emo’ is thought to be formed by clipping ‘-tional’ from the existing word ‘emotional’. Thus, some mass media argue that ‘emo’ inherits the same meaning as ‘emotional’, which is adjectivally concerned with emotions and feelings. Nevertheless, clipping refers to the word formation process in which a word is reduced or shortened without changing the semantic meaning of the original lexis (Fandrych, Reference Fandrych2008). We suggest that back-formation is proper to account for the morphological formation of ‘emo’. In lexicology, back-formation is the process of creating a new lexeme by removing actual or supposed affixes (a suffix or occasionally a prefix). ‘Emo’ is back-formed from the adjective ‘emotional’ or noun ‘emotion’, by removing the supposed ‘-tional’ and ‘-tion’ suffixes. This develops into the pattern for many English pairs (e.g., project/projection), where a verb is derived from a lexical supine stem and a noun ending in ‘-ion’ entered the language together. Back-formation is popular in folk etymologies when it rests on an erroneous perception of the morphological construction of longer vocabularies. 12 participants (80%) out of 15, considered that ‘emo’ is created by such back-formation by removing the suffix, i.e., ‘-tional’. Beyond that, back-formation differs from clipping in that the former may change the class or meaning of words, yet clipping does not connect functional and semantic changes. In section 5.1.3, ‘emo’ syntactically occurs as different word classes in communications. This also accounts for researchers’ assertion that ‘emo’ is, to a great extent, morphologically formed by back-formation.

The emergence of ‘emo’ was also phonetically motivated. Some participants claimed that they understood ‘emo’ [ˈiːməʊ] because it bears a resemblance of sounds to the Chinese sentence ‘一个人默默地哭’ (someone crying silently). In this case, the phonetic similarity between the English lexical item ‘emo’ and the Chinese sentence lies in the close front unrounded vowel /ˈiː/ in ‘emo’ and Pinyin final /i/ in ‘yi’ of the first Chinese character ‘一’ (underlined in Table 1). Besides, the diphthong vowel sound /əʊ/ in ‘emo’ shares a similar sound with the Chinese Pinyin final /o/ of the reduplicated character morpheme 默默 (underlined). Such a close phonetic resemblance (i.e., homophonization) (Chen, Reference Chen2015) and ‘easy to pronounce’ trigger the formation of ‘emo’. The phonetic similarity between ‘emo’ and ‘一默’ (yī mò) enables teenagers to voice their feelings, mainly regarding ‘aloneness’ and ‘loneliness’, through this informal lexical presentation.

Table 1. Phonetic similarity between ‘emo’ and ‘一默’ (yı¯ mò)

5.1.3 Syntactic analysis

Neologisms are used in various genres of speech; therefore, studying lexical innovations has brought about a multiplex classification where their sphere of usage is predominantly analyzed. All the instances of ‘emo’ were used as a code-mixing practice in Chinese utterances; thus, this section considers ‘emo’ as a constituent part of modern Chinese syntactic structure. The result shows that ‘emo’ processes three remarkable syntactic properties in different communicative contexts, most of which are used as verbs (n = 366/72%), followed by nouns (n = 90/18%) and adjectives (n = 51/10%).

In modern Chinese grammar, a verb (i.e., an action or a dynamic change) regularly occurs after the noun subject or main clause. In Extract (1), ‘emo’ is positioned after 开始 (kāi shǐ: start/begin), therefore, is perceived as a notional verb referring to conducting an ‘emo’ action. When ‘emo’ functions as a verb, it is generally followed by the modern Chinese auxiliary word 了(le: indicating the completion and achievement of an action being used tightly behind the verb) (see Extract [2]). Those instances of ‘emo’, as nouns, are frequently positioned as the object following verbs (predicates), shown in Extract (3). In this sentence, ‘emo’ occurs in the object position following the verb 拒绝 (jù jué: refuse), and it is rendered as a nominal lexis. The addresser expresses this rejection of the depressed mood and encourages herself to stay ‘happy every day’. The nominal use of ‘emo’ mainly occurs in clauses where the subject is always absent, e.g., 大 emo (dà: huge emo), and Extract (3). This mirrors the distinguishing feature of briefness for ‘emo’, representing a free, fast, and easy-to-use social contact element. The last syntactic constituent realized by ‘emo’ is adjectives that work as modifiers to denote state characteristics. Similarly to typical adjectives in the modern Chinese language, ‘emo’ in this study is frequently coupled with preceding adverbs such as 很 (hěn: very),非常 (fēi cháng: very),特别 (tè bié: particularly),最 (zuì: most), 好 (hǎo: very/well) (see Extracts [4] and [5]). In the modern Chinese language, both verbal and written forms, another typical formula for the adjective clause is: noun + 是 (shì: be) + adj + 的 (de: literally ‘of’), to describe or emphasize a (perceived) fact. Nevertheless, most current data on the adjective ‘emo’ are not connected with 的 to describe something (one example is shown in Extract [5]. In other words, ‘emo’ is less used in noun attribution, where it is a typical adjective preceding and modifying a noun.

(1) 我妈老胡思乱想,就自己一个人待着,然后就开始 emo。

(My mum is always imagining something, just being alone, then starting to emo.)

(2) 我 emo了。

(I emo (+ed/past tense).

(3) 拒绝 emo! Happy every day。

(Refuse (the) emo! Happy every day.)

(4) 哥哥,我今天感觉好 emo。

(Honey, I am feeling very emo today.)

(5) 这是我每天最 emo 的。

(This is the most emo (thing) in my everyday life.)

5.2 Discourse-pragmatic functions of ‘emo’

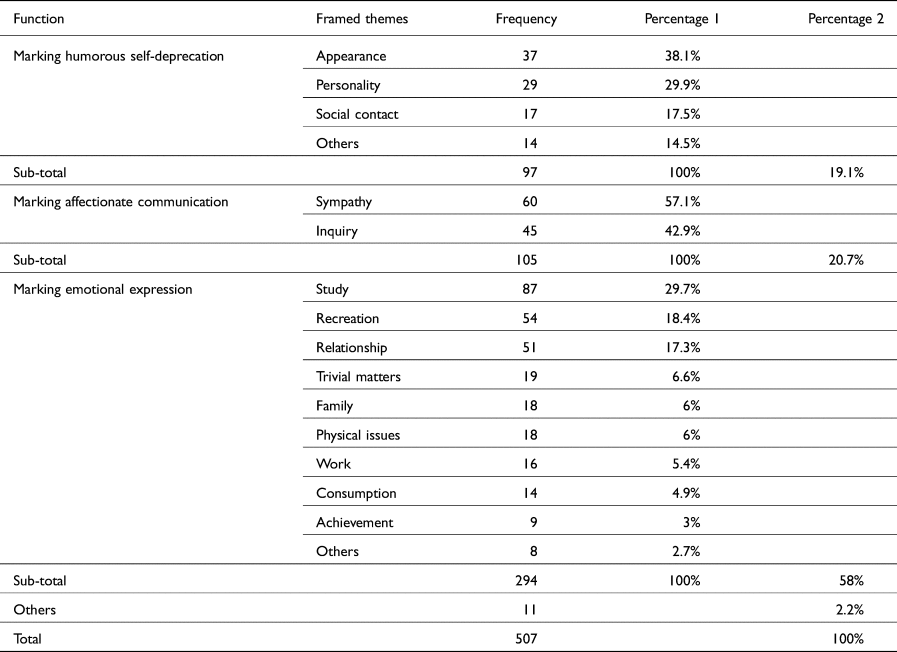

Pragmatic needs usually motivate language users to create new lexical units, namely lexical derivations. In diverse communicative contexts, bilingual speakers adapt lexical materials and select appropriate speech to facilitate themselves to express ideas and connotate implicatures (Martseva et al., 2018). Findings indicate that ‘emo’ realizes three primary pragmatic functions: as markers of humorous self-deprecation, affectionate communication and emotional expression (see Table 2). The distributions of the three macro functions are shown in Table 2. The themes, or topics framed in each pragmatic function, were identified according to the primary message in each ‘emo’-related conversation. To gain an in-depth interpretation of ‘emo’ usages, Table 2 also presents quantitative data regarding occurrence frequency and percentage proportion of each pragmatic function and framed theme.

Table 2. Distributions of ‘emo’ as discourse-pragmatic markers

Functions and framed themes that could not be accurately identified/classified were named ‘others’.

5.2.1 ‘Emo’ as a humorous self-deprecation marker

In pragmatics, humor often benefits in building rapport and creating close social relationships among interlocutors (Matwick & Matwick, Reference Matwick and Matwick2017). Self-deprecation, a common humor strategy, refers to ‘the act of belittling or undervaluing oneself and one's abilities, is a social behavior not uncommon in everyday interaction’ (Kim, Reference Kim2015: 398). As shown in Table 2, these salient aspects of humorous self-deprecation involve topics particular to addressers, such as physical appearance, personality, or interpersonal relationship. Notably, this pragmatic function is mainly used as a communicative behavior to save addressers’ positive face, or their desires to be liked or receive alignment. Individuals prefer to use self-deprecation, rather than self-praise, as humorous jokes to present themselves in a positive light (Boxer & Cortés–Conde, Reference Boxer and Cortés–Conde1997) as the speakers show that they can make jokes about the problems they encounter. Then they create a positive image of themselves, avoiding negative judgments and evaluations, to establish a conversational rapport.

In Extract (6), addresser A communicates her ‘emo’ because she thinks her face is too big and unattractive. A is intentionally doing the act of belittling or undervaluing her look. Next, A humorously defines her selfie as a ‘catfish’, meaning her image in the photo is not original but self-beautified or photo-edited by a mobile Beauty Camera. It is noticeable that A starts the conversation with ‘emo’ to avoid loss of face by either party by showing that she is making fun of her appearance humorously. The onomatopoeic rendering of laughter ‘hahaha’ in A2 strengthens the sense of a non-disparaging message. B also realizes that A's communicative intention is not ridicule. Thus, B does not exert much cognitive effort in replies, rather, just engages in face-saving by showing brief responses with ‘hahahaha’ to construct pleasant conversation, and appreciating A's positive sense of humor. Self-deprecating humor with ‘emo’ is essential to enjoy the humorous message in close friendship conversations. Speakers must utilize other rhetorical strategies (e.g., ‘hahahaha’ or ‘photo cheating’) for topic source evaluations to let interlocutors understand its humorous conversational implicature.

(6) A1: 我那天 emo 了,我脸也太大了吧,丑死了。

(I emo[+ed] that day, because my face is too big! Really ugly.)

B1: 哈哈哈哈,啥玩意?

(Hahahaha, what?)

A2: 然后,我用头发把我大脸挡上了,还用了美颜相机,真美,照骗啊, 哈哈哈。

(Then, I covered my big face with hair and used Beauty Camera, so beautiful, such a photo cheating [Internet catfish]! Hahaha.)

B2: 你可太逗了,哈哈哈哈。

(You are so funny. Hahahaha.)

5.2.2 ‘Emo’ as an affectionate communication marker

Affectionate communication is conceptualized as the intentional and overt enactment, expressions of feelings or symbolic behaviors through which individuals convey messages of care, love, fondness, and positive regard to each other (Floyd, Reference Floyd, Berger and Roloff2015: 24). ‘Emo’, as the affectionate communication marker, was mainly used by the communication addressee rather than the addresser (e.g., B in Extract [7]). Table 2 shows that two types of affectionate communication are relevant to ‘emo’: sympathy (n = 60) and inquiry (n = 45). Such ‘emo’ is much motivated by the addressee's desire to offer more significant support (supportive affection) rather than the humor sense to the addresser who is indeed involved in a negative mood and depressive emotion. Extract (7) comes from a conversation regarding an unsatisfactory exam result, in which A is sad in that she did not pass the all-important Teacher Qualification Certificate. Speaker B attempted to console A with cheerful words to offer encouragement, care and friendship in this ‘emo’ related response. Such emotional support and encouragement are classified as sympathy that is defined by the Youdao Chinese-English Dictionary (2022) as ‘if you have sympathy for someone who is in a bad situation, you are sorry for them, and show this in the way you behave toward them’ and ‘you show that you support someone’ by taking some action in sympathy with them (e.g., verbal). Regarding rhetorical construction, this kind of ‘emo’ is often collocated with some negative adverbs such as 别 (bié: do not) in Extract (7), 不要 (bú yào: do not). This rhetorical effect fosters comfort, confidence, and empathy toward people in low moods. Besides, ‘emo’ is also used in interrogative sentences such as ‘为什么 emo 呢?’ (wèi shén me emo ne: Why do you emo?). This question aims at performing an inquiry to elicit addressers to explain her/his situation. Therefore, its predominant communicative purpose is to be an information elicitation. Also, it conveys a message that ‘I care about you.’

(7) A1: 我太难受了,想哭。

(I am so depressed, wanna cry.)

B1: 咋了,这么难过?

(What's wrong? Why are you so sad?)

A2: 我教资考试 60 分。

(I scored 60 marks in the Teacher Qualification Certificate exam.)

……

B2: 没事,不是还有机会吗?仔细复习就好啦,都会好起来的,别 emo 啦。

(It's okay. There is still a chance, right? Just review carefully. It will be fine. Please don't emo lah.)

A3: 嗯嗯,但是最近过的太糟糕了。

(Yeah, but everything is terrible recently.)

B3: 没有关系,都会过去,我们还小,会长大,会变好,努力熬过去,就好了。加油!

(It doesn't matter, all will pass. We are still young. We will grow up, will become better. When we try to get through everything, it will be fine. Go for it!)

A4: 嗯嗯,好,加油!

(Yeah, okay, go for it!)

Concerning the semantic potential of this neologism, ‘emo’ is used to generalize a negative mood of someone instead of describing a specifical state of feeling. In Extract (7), B2, the addressee just responds ‘don't emo lah’ to downgrade the sharp sense of straightforward lexicons ‘depression’, ‘disappointment’, ‘down-hearted’, etc. Thus, the locus of ‘emo’ as an affectionate communication marker is possibly connected with the euphemism, and the aforesaid ‘humorous’ pragmatic function, to avert noticeably negative emotion-specific recognition patterns. It is also worth noting that most addressees utilizing ‘emo’ in this function would offer additional explanations to achieve the desired and effective affectionate outcomes. Diverse communicative strategies are used to fulfill this purpose, to name a few, strengthening belief (e.g., B3 in Extract [7]), assuming favorable conditions (e.g., B3 in Extract [7]), demonstrating societal responsibility, telling inspirational personal stories, presenting statistical evidence, to frame ‘positive aspect’ and motivate addressers to cheer up.

5.2.3 ‘Emo’ as an emotional expression marker

Regarding this pragmatic function, addressers use ‘emo’ to initiate the conversation to literally articulate a wide range of less optimistic feelings or stances such as sorrow, disappointment, anxiety, frustration, unhappiness, loneliness, helplessness, etc., in different contexts. As in Table 2, a common expressive-function practice is attributed to participants’ pressure and stress from academic studies (n = 87/29.7%), including assignments, end-of-year exam, postgraduate entrance exams, certification exams, and competitions (see Extract [8]). This verifies that academic stress becomes the primary cause of the ‘alarming’ conditions of college students (Reddy, Menon & Thattil, Reference Reddy, Menon and Thattil2018). This stress is manifested by depicting personal inadequacy and fear of failure. Uncertainty around academics and the rising pressure of competitions mean that many students do not feel confident about completing satisfactory studies. Recreations and interpersonal relationships are the following predominant domains that arouse teenagers’ ‘emo’ sentiments, without a remarkable distinction (n = 54, 51 respectively). In this section, recreation refers to things youngsters do to relax in their spare time, mostly watching TV dramas and movies, reading fiction, and listening to music. Extract (9) below comes from the addresser's reaction to a popular Chinese romantic drama. She uses verbal exaggeration, i.e., ‘my crying caused a headache’, to intensify the degree of ‘heart-wrenching’ of watching the drama, which intends to cause empathy of the addressee. Similarly, conversations on interpersonal relationships are also connected with ‘emo’. Teenagers tend to talk more about their life partners (see Extract [10]) rather than parents, friends, or roommates. Results presented in Table 2 denote that there exist notable differences in distinct dimensions of negative emotions among today's university students. Several subjects may result in their emotional negativity, such as interpersonal difficulties, physical health conditions, experiencing isolation, or even unclassifiable trivial matters (‘forgot to bring books to class’).

(8) A: 我最近被考研整 emo 了。

(Recently, I became emo because of the postgraduate entrance exam.)

(9) A: 我 emo 了,我刚看完《周生如梦》,这故事太虐了,哭的脑袋疼。

(I emo(+ed). I just finished watching Zhou Sheng Ru Meng (a Chinese romantic drama). This story is too heart-wrenching. My crying caused a headache.)

(10) A: 深夜 emo ……我和他分手了。

(Late-night emo……I and he broke up.)

6. Discussion

The initial finding of this multi-dimensional analysis seems to unravel the fact that patterns of lexical innovations are showing some parallels across English varieties in different bilingual contexts, including phonetic properties, morphological formations, syntactic analysis, and discourse-pragmatic functions (Oladipupo & Unuabonah, Reference Oladipupo and Unuabonah2020; Palacios Martínez, Reference Palacios Martínez and Ziegler2018; Pavlova & Guralnik, Reference Pavlova, Guralnik and Pavlova2020). Although by no means exhaustive, Figure 3 outlines a tentative analytical model for future discussions on lexical innovations or bilingual creativity regarding world Englishes, by initially concentrating on these four linguistic perspectives (see the inner frame around the core). It is observed that the word formation constitutes an essential dimension of lexis nativization, which denotes how English phonemes and morphemes develop into ‘being localized’ in the outer circle English world. What is noteworthy in the pragmatic use is that ‘emo’ refers to a relatively inexact indication of feelings or moods, which differs from loanwords presenting highly specialized vocabularies in English. The results suggest that Chinese university youngsters already have shared communicative knowledge about ‘emo’, even unconsciously, so it can be accessible to them to construct effective daily talk. With this, we assert that ‘emo’ can be recognized as a Chinese nativized English lexis whose original meanings are altered semantically in denotations and connotations.

Figure 3. Conceptual relationship among patterns to investigate lexical innovations

Concerning web-mediated lexical innovations, the prevalence of phonetic and morphological creativity should be possibly attributed to the playfulness and ‘ludicrousness’ of Internet expressions. This phenomenon of language play (Crystal, Reference Crystal1996) gains popularity in social networking and Internet communications among today's youngsters, constantly boosting new lexical forms and linguistic variations in bilingual circumstances. In China, young English learners are generally creative in using this foreign language and enjoy playing/experimenting with it. Thus, they coin new lexical units by adapting multiple linguistic features and extending discourse-pragmatic usages of lexical items. This mirrors their positive attitude towards Chinese-English hybridization and linguistic creativity in daily communication (Fang & Liu, Reference Fang and Liu2020). Chinese university youngsters strongly desire to associate themselves with the world community of young people who use distinctive communications. This quest for the multilingual identity and vanguard of new developments and trends is responsible for most of their behaviors in altering the language, notably at the lexical level (e.g., ‘emo’) (Palacios Martínez, Reference Palacios Martínez and Ziegler2018; Zhang, Reference Zhang2021).

Drawing upon the data collected from WeChat in China, this study illustrates the fact that Internet societies continually evolve and users create innovative lexical items to talk about novel practices. Online chatting is gradually recognized as a unique Internet-language ‘written speech’ (Crystal, Reference Crystal2001: 25). Some characteristic lexical innovations, such as ‘emo’, soon spread successfully and become part of the recognized lexicon, especially in web-mediated communications. The evidence also strengthens the multilingual standpoint that languages are undoubtedly and intimately related to particular social-cultural contexts, native language influences and language users (see the outer frame in Figure 3). Thus, language transformation or adaptation is ‘inevitable and unstoppable because human beings live in a permanent state of flux’ (Rodríguez Arrizabalaga, Reference Rodríguez Arrizabalaga2021: 17).

Though the innovative use of ‘emo’ is believed to connect with its original English sources, it is produced with remarkable differences and changes, in other words, linguistic variability (Kim, Reference Kim2015; Robertson, Reference Robertson2000; Zhang, Reference Zhang2021). This is mainly caused by the specific socio-cultural context where ‘emo’ is contextualized. Social contexts refer to a nested set of systems surrounding the language users, here Chinese society. Particular Chinese cultural norms, for instance, humor and interpersonal interaction norms, are linked with characteristics in the process of target language development. Second, the native language interferes with second/foreign language practices; thus, it is not isolated to be considered when elaborating on linguistic creativity of other languages. As a logographic system, the Chinese language surely resorts to different strategies in accommodating English usage in Chinese social settings. This is obviously true regarding the morphosyntactic features of ‘emo’. The intertwining between Chinese-language grammatical uses and English code-mixing demonstrates that this original English lexical item does not conform to the supposed English grammatical rules, thus revealing a feature of ‘stylized Chinese English’ (Su, Reference Su2003). We also introduce another analytical lens to the increasing interest in the experiences and trajectories of lexical innovations: language users’ characteristics. This term describes interpretations of the complexities of users in a specific context. In the present study, the university youngsters’ uses of ‘emo’ are closely tied to their studies, missions, interpersonal relationships, etc., which differentiates from other social groups.

In the realm of world Englishes or bilingualism, the findings also uncovered remarkable linguistic features and discourse-pragmatic facets of the novel establishment of ‘emo’, thus supporting the notion that Chinese English is dynamically changing (Fang, Reference Fang2008). Merging the insights of previous scholars, Albrecht (Reference Albrecht2021: 3) defines up-to-date Chinese English as:

[A] developing variety of English, which is subject to ongoing codification and normalization processes . . . It is characterized by the transfer of Chinese linguistic and cultural norms in discourse, syntax, pragmatics, lexis, and phonology.

It suggests that the process of linguistic nativization, conventionalization and legitimation, such as ‘emo’, of Chinese English is established by utilizing existing world English lexical resources to generate a multi-perspective alteration in particular Chinese contexts, and hereby mirrors indigenous Chinese social-cultural elements.

7. Conclusion

Today's bilingual studies have been transformed from a monolithic perspective of standard language to a pluralistic view of diverse emerged varieties. This study has cast light on the process and essence of innovations in the lexis of the emerging Chinese English by exploring the Internet buzzword ‘emo’ within university youngsters’ online communications. The study reveals that modern Chinese English is neologising interestingly. This encourages scholars to probe into the issues of neologies in Chinese English, and also lends significance to the academic understanding of more world English varieties. Present-day understanding of Chinese English is still not as established as other outer circle varieties. A comprehensive description of Chinese English is not yet possible; nevertheless, identifying features in this study might still offer valuable insights into likely trends in Chinese English and benefit future depictions of the entire linguistic landscape of Chinese English. Some knowledge of the findings in this study is beneficial to those non-Chinese English speakers who are befuddled by this popular lexical term in Chinese communicative contexts. Primarily to be qualitative rather than quantitative, the limitation of this study is that the data is of limited size, and was only collected in a particular participant group, i.e., female university youngsters. Therefore, a large corpus of data is suggested to be adopted to validate the findings reported in this study. Our analysis focused on the mobile media, i.e., WeChat, discourse; therefore, it would be significant to examine the verbal speech discourse to make more generalizations about the ‘emo’ usage as a lexical innovation.

YING QI WU holds a Ph.D. in Linguistics from the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya. He is currently a senior lecturer at School of Foreign Languages, Hebei Normal University for Nationalities, Chengde, China. His research interests are web-mediated linguistics, world Englishes, sociolinguistics and discourse analysis. His recent studies are published in Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, JATI-Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, etc. Email: [email protected]

YING QI WU holds a Ph.D. in Linguistics from the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya. He is currently a senior lecturer at School of Foreign Languages, Hebei Normal University for Nationalities, Chengde, China. His research interests are web-mediated linguistics, world Englishes, sociolinguistics and discourse analysis. His recent studies are published in Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, JATI-Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, etc. Email: [email protected]

QI SUN is currently a postgraduate student majoring in English Language Studies at the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics at the University of Malaya, Malaysia. His research interests include World Englishes, China English, and language attitudes. Email: [email protected]

QI SUN is currently a postgraduate student majoring in English Language Studies at the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics at the University of Malaya, Malaysia. His research interests include World Englishes, China English, and language attitudes. Email: [email protected]