No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

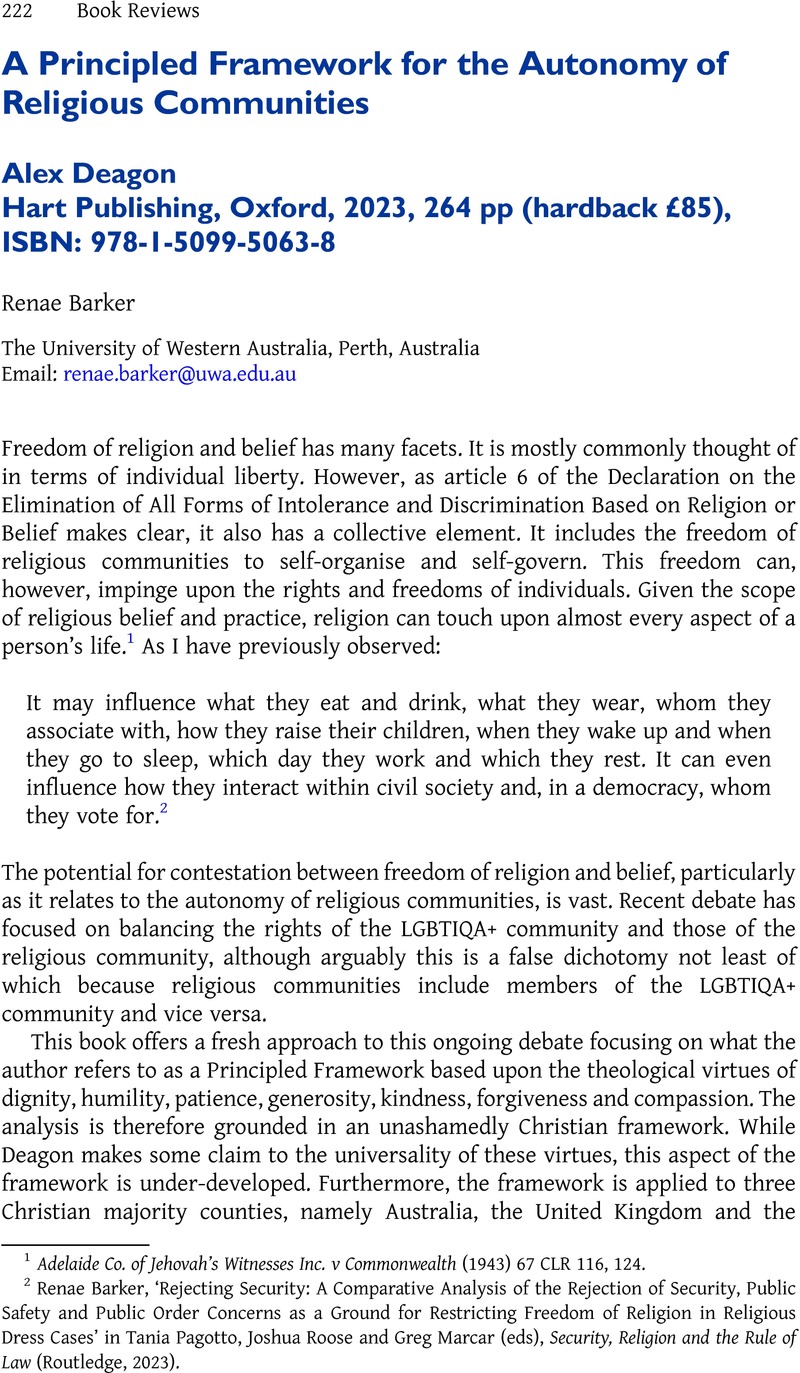

A Principled Framework for the Autonomy of Religious Communities Alex Deagon Hart Publishing, Oxford, 2023, 264 pp (hardback £85), ISBN: 978-1-5099-5063-8

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 May 2024

Abstract

- Type

- Book Review

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Ecclesiastical Law Society 2024

References

1 Adelaide Co. of Jehovah's Witnesses Inc. v Commonwealth (1943) 67 CLR 116, 124.

2 Renae Barker, ‘Rejecting Security: A Comparative Analysis of the Rejection of Security, Public Safety and Public Order Concerns as a Ground for Restricting Freedom of Religion in Religious Dress Cases’ in Tania Pagotto, Joshua Roose and Greg Marcar (eds), Security, Religion and the Rule of Law (Routledge, 2023).

3 See, for example, WC Durham and GG Scharffs, Law and Religion: National, International, and Comparative Perspectives (Aspen Publishing, 2019) 121–174.