Professor Zhang Zhongpei 張忠培 was a field archeologist, a Professor of archaeology at Jilin University, and a highly valued Ph.D. Director of scores of students. He also served in many influential capacities including as the Director of the Palace Museum in Beijing, the honorary director of the Palace Museum Research Institute, and the deputy director of the Palace Museum Academic Committee. Among archaeologists he is known through his many publications and through his twenty-year membership on the State Bureau of Cultural Relics which granted permits for archaeological projects thereby reshaping the course of fieldwork over the past few decades. Zhang Zhongpei passed away at the age of eighty-three on July 3, 2017 in Beijing.

In 1952 Zhang Zhongpei was admitted to the Department of Archaeology at Peking University, and after graduation in 1961 he became a faculty member in the History Department at Jilin University. In 1972 he founded the Department of Archaeology there and successively served as vice president of the Jilin University Graduate School, a Professor and Ph.D. Tutor. In 1987 he became the president of the National Palace Museum and in 2008 he was made the fifth council chair of the Chinese Archeology Association. He was awarded the title of “Scientific and Technological Expert with Outstanding Contributions” by Jilin Province, and became a member of the Archeology Section of the State Philosophy Social Science Planning Commission and a delegate to the Seventh National People's Congress. In 1991 was honored nationally for his outstanding contributions to his field.

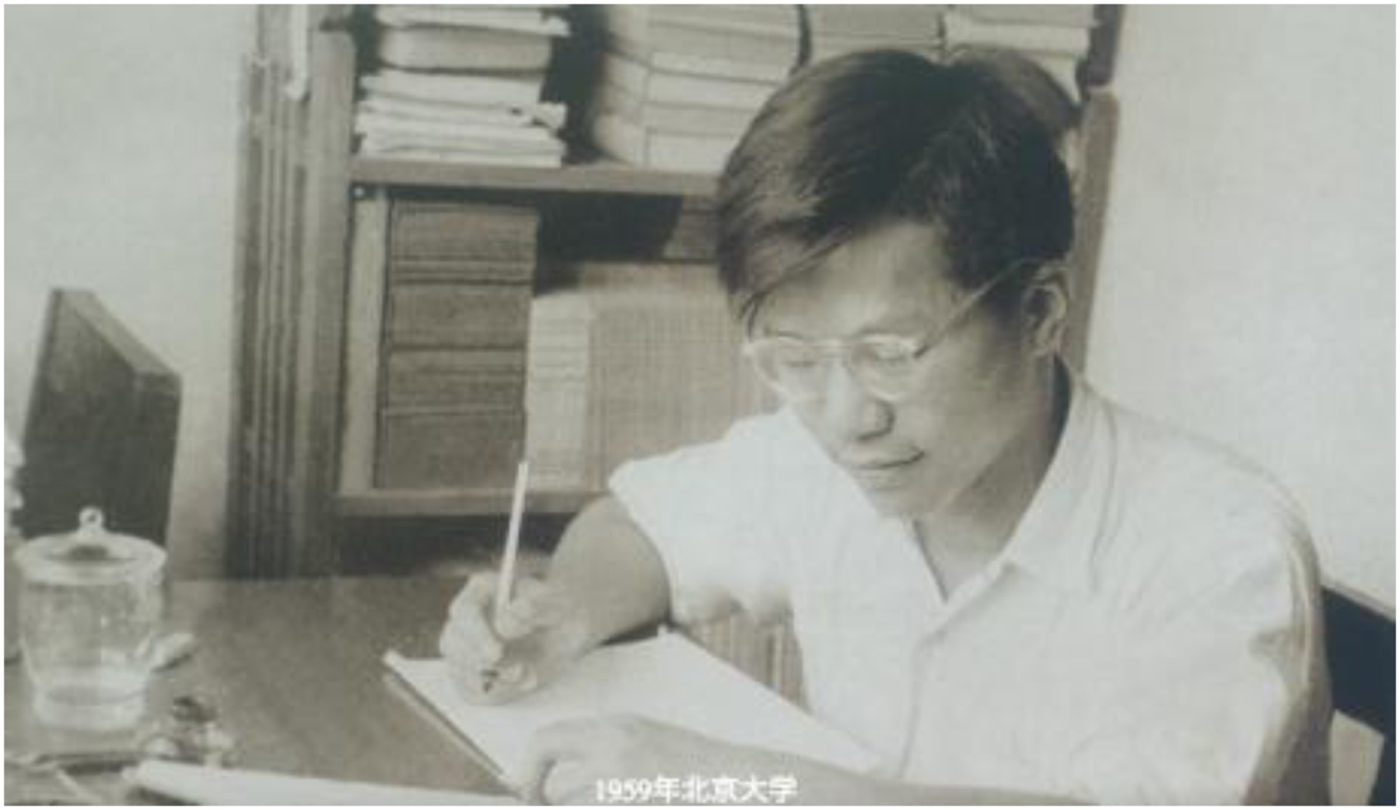

Figure 1. Zhang Zhongpei in 1957.

Zhang Zhongpei was born in August 1934 in Changsha, Hunan Province, where his lifelong intellectual and personal interests were forged. For instance, in his childhood, during the war of resistance against Japan, he was forced to change schools six times, and he reported that he began to care about national affairs during high school. In 1949, he organized a class of fourteen-year-old classmates to participate in a movement that called for the peaceful liberation of Changsha. He claimed that it was then that ideas about liberty, democracy, and equality as long-term objectives for China were fixed in his mind and spirit.

Beginning in 1958, Zhang Zhongpei presided over a large number of archaeological field projects, and he published more than 200 articles and numerous books about that work. His research objectives radiated from the moment of his coming of age and from the ideas of his teachers, the archaeologist Su Bingqi and the ethnologist Lin Yaohua, who worked among minority populations in China. Su Bingqi (1909–1997) argued for the regional development of Chinese civilization in at least six areas, each of which he suggested had its own cultural development and was in constant interaction with others. Zhang Zhongpei carried out and supported fieldwork that has tested and verified this idea and has inevitably forced other archaeologists to reconsider their traditional methodologies and unilinear framework for the development of Chinese civilization.

As a young student Zhang Zhongpei learned to think about how to analyze history through study of physical materials, particularly within the archaeological context of tomb organization and disposition of funerary objects, in order to understand issues of social organization, status of men and women, and family organization. His fundamental interest was in reconstructing early historical social structure and the morphology of social change in China. He finally proposed and documented several multi-centered and multi-cultural sequences and timelines for the prehistoric formation of Chinese cultures and their unification in the Qin and Han empires. His interpretations were frequently contrary to prevailing models at the time.

Figure 2. Zhang Zhongpei in 2015.

In 1999 he extended his reach to co-sponsor a cooperative field project with Jilin University, Inner Mongolia Cultural Relics Bureau, Hebrew University, and the University of Pittsburgh on a multi–year project to survey and excavate in eastern Inner Mongolia (Chifeng International Collaborative Archaeological Research Project–CICARP). The project developed and tested field methods that allowed for the reconstruction of the region's socio-political trajectory over a long period (third millennium b.c.e.–2nd century c.e.) and in an area that stood outside of the early dynastic apparatus of the Central Plain.

His pioneering work on the development of the Palace Museum began in 1987, when the State Council appointed him as the director of the National Palace Museum. In the space of two years, he sought to preserve the Palace Museum under the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, began to overhaul the organization of the museum in order to preserve its place as a repository for Chinese history, and promoted scientific and standardized management of the museum in order to preserve the integrity of its architecture, grounds and collections through cataloguing its contents.

As a colleague, Zhang Zhongpei was quick to point out that inheritance, absorption, integration, and innovation were the laws that guided historical and cultural evolution of all human societies. I personally was privileged to work with him in the CICARP field project in IMAR and often benefitted from his taste for debate that challenged the old paradigms. I also very frequently was invited to participate in another of his passions—his taste for good food! His many students and colleagues have benefitted and learned from his wise counsel and continue to pass along his lessons of perseverance, intellectual rigor, and honest debate.