No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

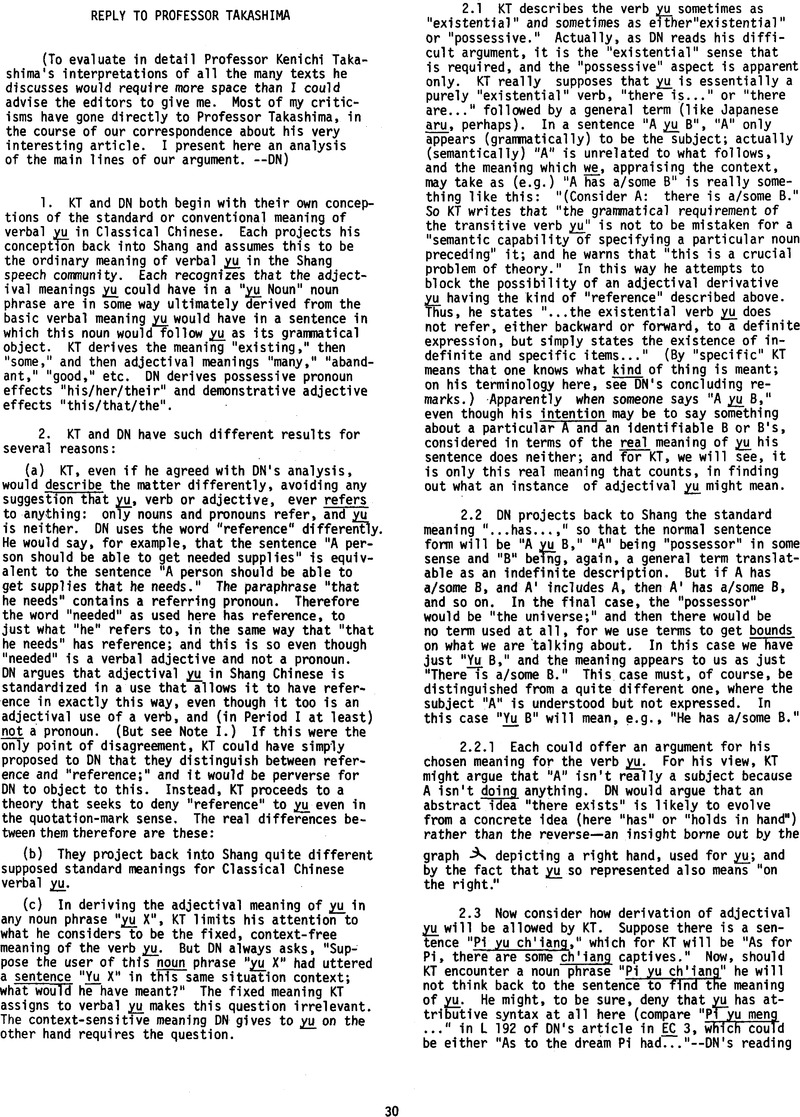

Reply to Professor Takashima

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 March 2015

Abstract

- Type

- Reply

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Society for the Study of Early China 1978

References

FOOTNOTES

Note I DN suspects that pronominally functioning yu in time evolves into the early archaic possessive pronoun chüeh![]() . This thesis conflicts with basic principles accepted in the reconstruction of the phonology of early Chinese. It will, therefore, have far-reaching consequences if it turns out to be right.

. This thesis conflicts with basic principles accepted in the reconstruction of the phonology of early Chinese. It will, therefore, have far-reaching consequences if it turns out to be right.

Note II On the matter of yu supposedly meaning “abundant,” DN would observe that on his reading of Kung-yang Huan 3/10 attributive yu does not occur there at all. Further, we must distinguish KT's attempt to derive a meaning “abundant” from a meaning “some,” from the possibility (fact, DN thinks) that verbal vu evolved a meaning “really have,” “have plenty of,” giving the predicate adjective sense “plentiful” in the Shih-Ching examples. That yu could come to mean “abuncdant” in this way in a Shang text is quite possible. So, also, one could argue (KT doesn't) that yu comes to mean “(regularly) sacrificed to,” and so, perhaps, “venerable,” before an ancestor term (e.g., “yu tsu”)--from the special Shang verbal sense of yu “make an offering to.” But nothing in any Shang text requires such assumptions as these. To make them would be to multiply meanings beyond necessity.

Note III Perhaps in saying (his article, 5.2 (1)) ‘appropriate translation “the,”’ DN should have added the caution that “the” is not, strictly speaking, a meaning of yu, but a translation strategy in handling the whole phrase. A yu phrase can sometimes be indefinite. But when “yu X” is interpreted as referring to the whole set of X's, or to the most important X (see 5.2.2), indefinite reference (for the whole phrase) is precluded, and then “the” is the natural “translation.”

Note IV The head noun “X” in a yu phrase is a general term. And KT seems to think that a general term (like mi, “deer”) must ordinarily be “indefinite,” because like an indefinite description it does not, so to speak, considered by itself, “pick out” one thing--unless it has come conventionally to function by itself as a name (like wang, “King,” perhaps). But calling a general term “indefinite” is a category mistake. It is descriptions, “the man,” “a dog,” that (being referring expressions) are definite or indefinite. “Man” and “dog” are neither. KT explicitly departs from this distinction near the end of III-1, in saying “[yu]… has been held” (by KT) “to introduce indefinite nouns,” after just having given several lists of yu phrases that he would translate using “the,” e.g., “yu mu” ![]() and “yu t'ien”

and “yu t'ien” ![]() , etc. (Incidentally, his translation of the former as “the mother(s),” evidently having in mind deceased “mother(s)” like “Mu Kuei,” is impossible for the only examples, i.e., in

, etc. (Incidentally, his translation of the former as “the mother(s),” evidently having in mind deceased “mother(s)” like “Mu Kuei,” is impossible for the only examples, i.e., in ![]() 182. As object of the verb yü

182. As object of the verb yü ![]() “yu mu” must refer to a living person, reasonably taken to be the same as the fu

“yu mu” must refer to a living person, reasonably taken to be the same as the fu![]() (“wife”) in

(“wife”) in ![]() 182 (11). KT's failure to artend to this undermines the whole of his criticism of DN's interpretation of

182 (11). KT's failure to artend to this undermines the whole of his criticism of DN's interpretation of ![]() at II.1.)

at II.1.)

Note V Professor Takashlma has suggested to me that ![]() , “Yü Fu yü yu ch'i,” is embarrassing to my theory, for on that theory the prima facie meaning would be “We should yü-supplicate for the Fu to her ch'i” and the most probable meaning for both fu and ch'i is “wife.” And, of course, a wife cannot have a wife. The two translations I offer avoid the difficulty, to be sure. But the second (identifying

, “Yü Fu yü yu ch'i,” is embarrassing to my theory, for on that theory the prima facie meaning would be “We should yü-supplicate for the Fu to her ch'i” and the most probable meaning for both fu and ch'i is “wife.” And, of course, a wife cannot have a wife. The two translations I offer avoid the difficulty, to be sure. But the second (identifying ![]() as

as ![]() , and interpreting it as

, and interpreting it as ![]() or perhaps

or perhaps ![]() ) is obviously problematic. The first takes yu as “definite article” in Its “honorific” or “distinguishing” effect, and this is an important possible Interpretation allowed by both our theories-although Professor Takashlma has, quite properly, given special attention to it. But one could object here that this interpretation would require supposing that yu ch'i was an “established phrase,” even though this is the only available example of it.

) is obviously problematic. The first takes yu as “definite article” in Its “honorific” or “distinguishing” effect, and this is an important possible Interpretation allowed by both our theories-although Professor Takashlma has, quite properly, given special attention to it. But one could object here that this interpretation would require supposing that yu ch'i was an “established phrase,” even though this is the only available example of it.